Abstract

Background

The FMR1 premutation, caused by a CGG trinucleotide repeat expansion on the FMR1 gene, has been identified as a genetic risk factor for mood and anxiety disorders. Building on recent studies identifying increased risk for mood and affective disorders in this population, we examined effects of potential protective factors (optimism, religion, hope) on depression and anxiety diagnoses in a prospective, longitudinal cohort.

Methods

Eighty-three females with the FMR1 premutation participated in the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Disorders at two time points, three years apart. Participants also completed measures of optimism, religion, personal faith, hope, and child and family characteristics. We used logistic regression to examine correlates of major depressive disorder (MDD) and anxiety disorders at the initial assessment, as well as predictors of the diagnostic course over time.

Results

Lower optimism and higher religious participation relevant to FXS at the initial assessment were associated with a lifetime history of MDD. Lower optimism also predicted the occurrence and reoccurrence of an anxiety disorder three years later.

Conclusions

In women with the FMR1 premutation, elevated optimism may reduce the occurrence or severity of MDD and anxiety disorders. These findings underscore the importance of supporting mental health across the FMR1 spectrum of involvement.

Keywords: FMR1 premutation, anxiety, depression, optimism, fragile X syndrome, religion

Introduction

Mood and anxiety disorders are among the most commonly diagnosed conditions in the United States, with depression identified as the leading cause of disease-related disability among women (Kessler, 2003). Although the longitudinal course of mood and anxiety disorders is well-established (Fichter et al., 2008; Klein et al., 2008; Vuorilehto et al., 2005), the majority of studies to date have focused on risk factors, and limited information is available on protective factors that may intersect with genetic risk to protect against the emergence and severity of psychopathology.

The present study addresses this gap by examining protective factors that moderate the emergence of psychopathology in women with the FMR1 premutation. The FMR1 premutation is characterised by an abnormal expansion of 55–200 CGG trinucleotide repeats on the promotor region of the FMR1 gene. Although “premutation carrier” status is not defined by a profile of disability, these individuals are at risk to conceive a child with fragile X syndrome (FXS), a neurogenetic syndrome associated with intellectual disability, autism, and attention deficits. Fragile X syndrome is relatively rare (1:4,000 males; Hagerman et al., 2009), yet the premutation is much more common, affecting up to 1:151 females (Seltzer et al., 2012). Importantly, a growing body of evidence suggests that premutation carriers exhibit increased elevated risk for mood and anxiety disorders (Loesch et al., 2015; Roberts et al., 2009), even before having a child with FXS (Roberts et al., 2009). In addition, evidence suggests that the prevalence of both mood and anxiety disorders increases over time in women with the FMR1 premutation (Roberts et al. 2015). Thus, studying protective factors that may reduce risk in women with the FMR1 premutation is a public health concern, with potential to inform treatment that could substantially improve quality of life for affected individuals.

Prevalence and Predictors of Depression and Anxiety in the FMR1 Premutation

Elevated risk for mood and anxiety disorders is well established in premutation carriers, making the FMR1 premutation one of the most prevalent heritable risk factors for psychopathology. In our initial work using the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID), we reported that 43% of women with the FMR1 premutation (n=93) met diagnostic criteria for a major depressive disorder (MDD), and 29% met criteria for an anxiety disorder (Roberts et al., 2009). In our follow-up study characterizing changes in diagnoses over a three year span, we reported a 17% increase in the presence of MDD and a 25% increase for anxiety disorders (Roberts et al., 2016). Similarly elevated affective features have been reported across multiple premutation samples (Cornish et al., 2015; Loesch et al., 2015; Hunter et al., 2012) with reported rates of affective disorders as high as 65% for MDD and 52% for anxiety (Bourgeois et al., 2011).

The high rate of affective disorders among women with the FMR1 premutation likely reflects a complex set of factors, including life stressors that may be mediated by cognitive and genetic variables (Cornish et al., 2015; Loesch et al., 2015). Increased child problem behaviour over time, divorced marital status, and genetic factors (mid-range CGG repeat length) have been associated with the presence and increase of MDD (Loesch et al., 2015; Mailick et al., 2014; Roberts et al., 2016). These patterns are similar to studies of mothers of children with intellectual disabilities in which depressive symptoms are consistently predicted by stress, coping styles, maternal health, and family support (Bailey et al. 2007). Anxiety disorders in premutation carriers have been associated with increased stress related to child factors, including the number of children affected by fragile X syndrome and the severity of problem behaviour exhibited by the affected children (Roberts et al., 2009), along with mid-range CGG repeat expansions (Loesch et al., 2015; Mailick et al., 2014) and the presence of Fragile X Associated Tremor/Ataxia Syndrome (FXTAS) (Bourgeois et al., 2011). These multiple sources of risk underscore that premuation carrier mothers may experience multiple sources of stress simultaneously, including parenting a child with a disability, experiencing reproductive health challenges, and caring for an aging parent with FXTAS. Thus, experiential and genetic vulnerabilities likely converge to create a complex system of risk that contributes to elevated rates of psychopathology.

Despite these vulnerabilities, most women with the FMR1 premutation report a generally positive quality of life (Wheeler et al., 2008) and score in average range on many screening tools for parenting-related risks (Bailey et al., 2008). These trends speak to resilience and individual differences, highlighting the importance of considering both risk and protective factors that contribute to psychopathology. Indeed, in mothers without the permutation who have children with disabilities, protective factors have a demonstrated relationship to psychological well-being. Specifically, increased optimism predicts positive maternal outcomes in mothers of children with autism (Ekas, Lickenbrock, & Whitman, 2010), and children with developmental delay (Baker, Blacher & Olsson, 2005). Similarly, high hope scores predict low levels of depressive symptoms in mothers of children with intellectual disability (Lloyd & Hastings, 2009). Extending this work to women with the FMR1 premutation may inform interventions to address the elevated rates of psychopathology in this population by addressing unique genetic vulnerabilities and environmental challenges.

Although no longitudinal studies have investigated the prospective association between protective factors and mental health in premutation carriers, both elevated optimism and hope have been concurrently associated with lower depressive and anxiety symptoms (Bailey et al., 2008). More specifically, hope correlates with enhanced quality of life (Wheeler et al., 2008), and partner support predicts more adaptive responses to stress (Bailey et al., 2015). A next phase for this work is to establish whether these protective factors may buffer the longitudinal time course of mental health symptoms in women with the premutation, measured using gold-standard diagnostic interviews, thus informing whether variability in protective factors can be leveraged to prevent the onset and reoccurrence of mental health risks in this population.

The present study

The present study examines the potential protective effects of optimism, religion, and hope on the expression and stability of psychopathology in a prospective, longitudinal cohort of women with the FMR1 premutation. We report new data from a previously characterised cohort who have at least one child affected by FXS (Roberts et al., 2009; Roberts et al., 2016). The initial published study on this cohort characterised rates of mood and anxiety disorders in these women (n=93, Roberts et al., 2009), followed by a subsequent study on the stability of diagnoses across a three year follow-up interval (n=83, Roberts et al., 2016). Here, we extend this work by examining the association between protective factors and longitudinal trajectories of risk in the Roberts et al 2016 sample to better understand resilience. Our specific research questions were:

Are protective factors (optimism, religion, hope) associated with the lifetime presence of MDD and anxiety in women with the FMR1 premutation?

What protective factors (optimism, religion, hope) are associated with reduced emergence of an affective disorder, over time, in women with the FMR1 premutation?

We hypothesised that women who reported high levels of protective factors at Time 1 would have a lower initial rates of affective disorders at Time 1, as well as lower probability of meeting criteria for a disorder by the end of the subsequent three year surveillance period (Time 2).

Methods

Participants

Data were drawn from a longitudinal project investigating child and maternal variables in families with a child with FXS, previously characterised in Roberts et al., 2009 and 2016. The sample at Time 1 consisted of 93 females, aged 20–46 (M=35.13). These 93 women are the same participants used by in the 2009 paper by Roberts and colleagues, with 83 of these participants completing a follow up assessment three years later (Roberts et al., 2016). Attrition (n=10) was due to a lack of time or interest, with no difference in the rate of affective disorders for individuals who did and did not participate at the follow-up (60% vs. 59% respectively). The final sample for this study included 83 females, aged 20–45 (M=35). Table 1 includes additional demographic information, also reported in Roberts et al 2016. Seventy-nine mothers also provided genetic reports indexing CGG repeat length (M=91.84, SD=17.44, range 68–163). Demographic features were previously examined in this sample in relation to Time 1 psychopathology (Roberts et al., 2009) and change across the interval between Time 1 and Time 2 (Roberts et al., 2016). Thus, we determined whether to include each of these features as covariates to ensure effects related to our primary variables of interest – protective factors – were not accounted for by demographic features.

Table 1.

Subject Sociodemographic Characteristics

| Characteristics | Time 1 | Time 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Chronological Age | ||

| M | 34.96 | 38.35 |

| SD | 5.29 | 5.31 |

| Range | 20–45 | 23–48 |

| Marital Status at Time One | ||

| Married | 73% | 67% |

| Divorced/Separated | 19% | 26% |

| Never Married/Engaged | 7% | 7% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 79.5% | |

| African-American | 17.9% | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1.2% | |

| Other | 2.4% | |

| Low Income* | 23% | 24.6% |

| Education | ||

| Completed Grades 8–11 | 3.5% | |

| High School Graduate | 4.8% | |

| Some College or More | 91.6% | |

| Number of Children with FXS | ||

| 1 | 66.3% | 64.2% |

| 2 | 28.9% | 30.9% |

| 3 | 4.8% | 4.8% |

DHHS defines a family as low income if their income is 200% of the federal poverty line

Measures

Mood and Anxiety Disorders

The presence of mood and anxiety disorders was assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders (non-patient edition; SCID-NP), a semi-structured interview used to evaluate the current and lifetime presence of DSM-IV, Axis I disorders. The SCID-NP is a widely used measure which systematically reviews current and lifetime psychiatric symptomology. The mood and anxiety sections were used in the current study. Inter-rater reliabilities for the SCID-NP range from 0.57 to 1.00 and test-retest reliabilities range from 0.35 to 0.78 (First et al., 2002; SCID). In a study of longitudinal reliability of the SCID, estimates ranged from .71–1.00 (“good” to “excellent”; Zanarini & Frankenburg, 2001). The SCID has successfully been used within a longitudinal design in several other studies (Fichter & Quadflieg, 2005; Koenig, 2006) including those with fragile X (Roberts et al., 2009; Bourgeois et al., 2011). As detailed previously (Roberts et al., 2009, 2016), interviewers underwent extensive training, and all interviews were reviewed by the director of the data collection core to ensure diagnostic accuracy. Interviews that resulted in a diagnosis, or interviews which were borderline for a diagnosis, were further reviewed by a consulting psychiatrist. Any questions raised by the reviewers were resolved by follow-up phone calls to the participants.

In the current study, lifetime presence of a disorder was defined as meeting criteria for a disorder at any time, including currently. Current presence was defined a meeting criteria for a disorder with symptoms present within 30 days of the interview. Consistent with previous studies with this sample, we examined two primary dependent variables: (1) presence of MDD, and (2) presence of an anxiety disorder (panic, social phobia, agoraphobia, post-traumatic stress, specific phobia, generalised anxiety). Individual anxiety disorders could not be examined separately because there were not enough participants who met diagnostic criteria for any one category to sufficiently power an analysis. Mood and anxiety disorders were coded as categorical variables with 1 indicating the presence of the disorder and 0 indicating absence.

Optimism

Optimism, defined as positive generalised expectations about the future, was measured using the Life-Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R; Snyder et al., 1994). The LOT-R consists of 10 Likert-scale items, including 4 filler items that yield a total optimism score from 0 to 24. Higher scores indicate more optimism. The LOT-R has been demonstrated to have good internal and test-retest reliability (.76 and .79 respectively; Scheier & Carver, 1985) and moderately correlates with other optimism measures (Hjelle et al., 1996). The internal consistency of the LOT-R in the present sample was α=.84. The average score on the LOT-R was 14.92 (SD=4.70, range 2–24).

Religious Experience Related to FXS

Two components of religious experiences related to FXS, institutional religion and personal spirituality and faith, was assessed using an adapted version of the Fewell Religion Scale (FRS; Fewell, 1986). The FRS can be tailored for use in any population by specifying how components of religion relate to specific life events. In the current study, we specified questions to examine maternal use of formal religion and personal faith as sources of support after learning that a child has FXS, with items such as “How much has your religion or faith helped you to understand and accept having FXS in your family?” The measure has two empirically derived subscales; one being religion as an institution (Religious Participation) and the other being religion as a personal faith (Personal Faith). Twelve items (6 per scale) are used to generate the two subscales, which each range from 6–30 (high indicating more religiosity). Previous studies have reported internal consistencies ranging from .64 to .93 (Michie & Skinner, 2010; Skinner et al., 2001). The internal consistency of the FRS in our sample was α= .88 (Religious Participation) and .93 (Personal Faith). The average score on Religious Participation was 13.53 (SD=5.58, range 6–28) and the average score on Personal Faith was 21.69 (SD=7.12, range 6–30).

Hope

Hope, defined as the perception that goals are attainable and that successful paths can be determined to reach those goals, was assessed using the Trait Hope Scale (Snyder et al., 1996). The THS is composed of 12 items; four agency items, four pathways items, and four filler items. Eight items (e.g., “I can think of many ways to get the things in life that are important to me”) are used to generate a total hope score that ranges from 8 to 64. The THS exhibits high internal reliability (.82; Chang & DeSimone, 2001) and test-retest reliability (.85 over a 3-week interval, .73 over an 8-week interval, and .76 to .82 over a 10-week interval; Snyder, et al., 1991). The internal consistency of THS in our sample was α=.84. The average score on the THS was 48.51 (SD=8.79, range 27–62).

Additional Family Characteristics

Child problem behaviours were measured using the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991) Total Problem Behaviors score. Total Problem Behaviors are reported as T scores, with scores 60–63 indicating borderline clinical problems and scores above 63 indicating clinical problems. The average T score in our sample was 56.72 (SD=10.21, range 27–75). Ten participants (12%) had a child rated in the borderline clinical problem range, and 25 participants (30%) had a child rated in the clinical range. Maternal cognitive abilities were measured using the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) two-subscale full-scale intelligence quotient (IQ). Average intelligence quotient was 106.90 (SD=12.84, range 73–131).

Procedure

Data collection procedures are detailed in Roberts et al., 2009 and 2016 but are described in brief here. Each assessment was conducted in the family’s home over two days. Time 1 and Time 2 assessments were separated by approximately 3 years. Rating scales were mailed to the families two weeks prior to the visit and collected during the assessment visits. The SCID interviews were completed in person on the second interview day of each visit to allow time the interviewer to establish rapport. All data collection procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board, and participants provided consent prior to the study.

Analytic Strategy

Analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We first examined descriptive statistics and variable intercorrelations to inform data transformation and model specification. Next, we used a series of logistic regression models to test our hypothesis that higher levels of protective factors (optimism, religious experience related to FXS, hope) would predict (1) lower lifetime presence of MDD and anxiety at Time 1 and (2) lower rates of MDD and anxiety emergence during the three-year surveillance period between Times 1 and 2. Separate models were constructed for MDD and anxiety. Descriptive sample characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

Results

Data Transformation and Preliminary Analyses

Continuous variables were screened for normality and three were log-transformed to minimise skew: CGG repeat length, child problem behaviours, and income. All continuous predictors were centered and standardised to reduce nonessential multi-collinearity. Preliminary correlations among predictor variables are detailed in Table 2. Preliminary analyses indicated significant associations between primary variables and a number of demographic features, which were included as covariates in subsequent models: maternal age, maternal IQ, family income, and child problem behaviours, maternal marital status, and maternal education. The remaining demographic characteristics are reported descriptively but were not covaried in analyses due to nonsignificant association with our primary predictors (CGG repeats, child autism symptoms, race). We also examined whether core predictors differed across women with low (60–80; n=22), mid-range (80–100, n=34) or high (>100; n=23) CGG repeats given evidence that women with mid-range repeats exhibit elevated psychological and medical risks (Roberts et al. 2009; Loesch et al. 2014). Groups did not differ in optimism (Kruskal-Wallis X2(2)=1.37, p=.50), hope (X2(2)=.20, p=.90), personal faith (X2(2)=2.40, p=.30), or religious participation (X2(2)=2.80, p=.25). Participants with one versus more than one child with FXS also did not differ in levels of optimism (Wilcoxon two-tailed Z=−.86, p=.39), personal faith (Z=1.52, p=.13), religious participation (Z=1.44, p=.15), and hope (Z=.12, p=.90). Thus, CGG repeats and number of children with FXS was not covaried in subsequent models.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix of Predictor Variables

| Optimism | Personal Faith | Religious Participation |

Hope | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimism | -- | |||

| Personal Faith | .16 | -- | ||

| Religious Participation | .14 | .59* | -- | |

| Hope | .46* | .19^ | .19^ | -- |

| Maternal Age | .17 | .13 | .06 | .19^ |

| Maternal IQ | .12 | .17 | .21* | .06 |

| Income | .23* | .06 | .02 | .26* |

| CGG Repeats | −.02 | −.11 | −.11 | .03 |

| Child Problem Behaviours | −.22* | .17 | .23* | −.15 |

| Child Autism Symptoms | −.06 | .04 | .05 | .06 |

| Child Age | −.04 | .16 | .09 | −.02 |

p<.05,

p<.10;

Time 1 Initial Prevalence

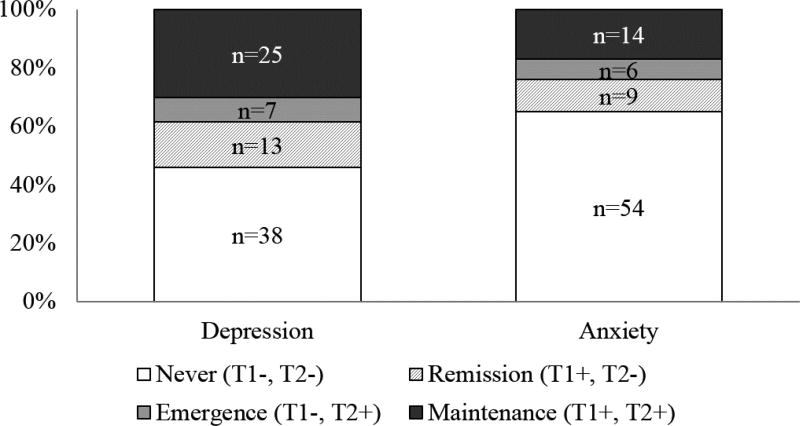

We next constructed two logistic regression models to test whether lifetime history of depression or anxiety at Time 1 was predicted by four protective factors: (1) optimism, (2) personal faith as related to FXS, (3) participation in organised religion as related to FXS, and (4) total hope. Figure 1 depicts the longitudinal course of MDD and anxiety diagnoses between Time 1 and Time 2. Specific diagnostic classifications are presented in Table 3, and results of logistic regression models are presented in Table 4. Overall models were significant for both MDD [Χ2 (8)=23.39, p=.003] and anxiety disorders [Χ2 (8)=26.21, p=.001]. At Time 1, lifetime history of MDD was associated with lower optimism (absent x̄=16.27, SD=3.33; present x̄=13.32, SD=5.57) and higher participation in religion in relation to FXS (absent x̄ =12.36, SD=4.68; present x̄ =14.92, SD=6.26). Holding other variables constant, the odds of lifetime MDD at Time 1 decreased .43 with 1 SD increase in optimism (4.70 points on the LOT-R) and increased 2.52 with 1 SD increase in religious participation relative to FXS (5.58 points on the FEWS). Lifetime history of anxiety was marginally associated with higher child problem behaviours, lower hope, and higher maternal brief IQ.

Figure 1.

Longitudinal patterns of depression and anxiety among women with the FMR1 premutation (n=83)

Table 3.

Summary of Longitudinal SCID Data (N=83)

| DSM-IV Disorder | % (n) Never BL−, FU− |

% (n) Remission BL+, FU− |

% (n) Incidence BL−, FU+ |

% (n) Maintenance BL+, FU+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mood Disorders | 40.9 (34) | 18.1 (15) | 8.4 (7) | 32.5 (27) |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 45.8 (38) | 15.7 (13) | 8.4 (7) | 30.1 (25) |

| Bipolar Disorder | 96.4 (80) | 1.2 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 2.4 (2) |

| Dysthymic Disorder | 98.8 (82) | 1.2 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) |

| Minor Depressive Disorder | 98.8 (82) | 1.2 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) |

| Anxiety Disorders | 65.1 (54) | 10.8 (9) | 7.2 (6) | 16.9 (14) |

| Panic Disorder | 91.6 (76) | 3.6 (3) | 1.2 (1) | 3.6 (3) |

| Panic Disorder w/Agoraphobia | 94.0 (78) | 1.2 (1) | 2.4 (2) | 2.4 (2) |

| Agoraphobia without Panic | 96.4 (80) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 3.6 (3) |

| Social Phobia | 90.4 (75) | 3.6 (3) | 1.2 (1) | 4.8 (4) |

| Specific Phobia | 92.8 (77) | 2.4 (2) | 2.4 (2) | 2.4 (2) |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | 97.6 (81) | 1.2 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 1.2 (1) |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 94.0 (78) | 4.8 (4) | 1.2 (1) | 0.0 (0) |

| Generalised Anxiety Disorder | 89.2 (74) | 2.4 (2) | 4.8 (4) | 3.6 (3) |

| Any Mood or Anxiety Disorder | 33.7 (28) | 18.1 (15) | 7.2 (6) | 41.0 (34) |

BL=Baseline, FU=Follow-U

Table 4.

Results of Logistic Regression Models

| Lifetime MDD at Time 1 | Lifetime Anxiety at Time 1 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | B | S.E. | Wald | p | OR | 95% CI | B | S.E. | Wald | p | OR | 95% CI |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Optimism | −0.85 | 0.35 | 5.76 | 0.02 | 0.43 | 0.21–0.86 | −0.20 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.56 | ||

| Religion Participation | 0.93 | 0.37 | 6.16 | 0.01 | 2.52 | 1.21–5.24 | 0.21 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.56 | ||

| Personal Faith | −0.20 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.43 | 1.58 | 0.21 | ||||

| Hope | −0.19 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.56 | −0.61 | 0.37 | 2.78 | 0.10 | ||||

| Brief IQ | 0.13 | 0.34 | 0.15 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.41 | 2.71 | 0.10 | ||||

| Maternal Age | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.47 | −0.03 | 0.34 | 0.01 | 0.94 | ||||

| Income | −0.61 | 0.37 | 2.70 | 0.10 | −0.20 | 0.40 | 0.24 | 0.62 | ||||

| Child Problem Behaviours | −0.12 | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.69 | 0.74 | 0.40 | 3.38 | 0.07 | ||||

| Marital (Married v. Sep) | −0.29 | 0.83 | 0.12 | 0.72 | −0.78 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.36 | ||||

| Marital (Divorce v. Sep) | −1.44 | 1.49 | 0.94 | 0.33 | 0.75 | 1.79 | 0.18 | 0.68 | ||||

| Education (<HS v College) | 0.17 | 1.33 | 0.02 | 0.90 | −1.49 | 1.87 | 0.64 | 0.43 | ||||

| Education (>HS v College) | 0.21 | 0.69 | 0.10 | 0.76 | −0.20 | 0.78 | 0.07 | 0.80 | ||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recent MDD at Time 2 | Recent Anxiety at Time 2 | |||||||||||

| Predictors | B | S.E. | Wald | p | OR | 95% CI | B | S.E. | Wald | p | OR | 95% CI |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| MDD/Anxiety at Time 1 | −2.11 | 0.71 | 8.72 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.03–0.49 | −3.58 | 1.05 | 11.60 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00–0.22 |

| Optimism | −0.64 | 0.43 | 2.24 | 0.13 | −1.15 | 0.48 | 5.85 | 0.02 | 0.32 | 0.13–0.80 | ||

| Religion Participation | 0.65 | 0.43 | 2.27 | 0.13 | −0.54 | 0.57 | 0.88 | 0.35 | ||||

| Personal Faith | −0.44 | 0.44 | 0.97 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.63 | ||||

| Hope | 0.15 | 0.44 | 0.12 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 1.44 | 0.23 | ||||

| Brief IQ | −0.03 | 0.39 | 0.01 | 0.94 | −0.32 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 0.54 | ||||

| Maternal Age | 0.78 | 0.39 | 3.98 | 0.05 | 2.19 | 1.01–4.71 | 0.56 | 0.48 | 1.36 | 0.24 | ||

| Income | 0.09 | 0.45 | 0.04 | 0.84 | −0.27 | 0.50 | 0.29 | 0.59 | ||||

| Child Problem Behaviours | 1.06 | 0.47 | 4.95 | 0.03 | 2.87 | 1.13–7.29 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.00 | 0.99 | ||

| Marital (Married v. Sep) | 0.11 | 1.01 | 0.01 | 0.91 | −0.72 | 1.06 | 0.46 | 0.50 | ||||

| Marital (Divorce v. Sep) | −1.89 | 1.90 | 0.99 | 0.32 | −13.56 | 343.10 | 0.00 | 0.97 | ||||

| Education (<HS v College) | 2.89 | 1.59 | 3.31 | 0.07 | 1.66 | 1.70 | 0.95 | 0.33 | ||||

| Education (>HS v College) | 1.04 | 0.88 | 1.41 | 0.24 | −0.45 | 0.97 | 0.21 | 0.65 | ||||

Longitudinal Change

We next examined whether these same protective factors predicted change in MDD or anxiety status over time. The dependent variable for these predictive models was the presence of MDD or any anxiety disorder between Times 1 and 2, controlling for lifetime presence of MDD or any anxiety disorder at Time 1. Therefore, each model was interpreted as the effect of the variable (i.e. optimism) on the probability of the occurrence of MDD or anxiety between Time 1 and Time 2, controlling for whether the individual met criteria for MDD or anxiety at Time 1. The overall models for MDD [Χ2 (9)=39.89, p < .001] and anxiety [Χ2 (9)=36.40, p < .001] were significant. Controlling for lifetime MDD at Time 1, recent MDD at Time 2 was associated with the higher child problem behaviours (absent x̄=53.75, SD=10.20; present x̄=61.47, SD=8.37) and maternal age (absent x̄=34.85, SD=5.53; present x̄=36.61, SD=4.78). Controlling for lifetime anxiety at Time 1, recent anxiety at Time 2 was associated with lower optimism (absent x̄=15.81, SD=4.16; present x̄=12.10, SD=5.27). Holding other variables constant, the odds of recent anxiety at Time 2 decreased .32 with 1 SD increase in optimism (4.70 points on the LOT-R).

Discussion

The present study provides new evidence that protective factors may reduce risk for the emergence of psychopathology in women with the FMR1 premutation. Consistent with our hypotheses, higher optimism was associated with lower risk for lifetime MDD at Time 1 as well as less risk for an anxiety disorder at Time 2. Notably, both associations persisted when controlling for child problem behaviours, family income, and maternal age, brief IQ, marital status, and education. Furthermore, the association between optimism and lower anxiety risk at Time 2 persisted when controlling for lifetime history of anxiety disorders at Time 1, demonstrating the predictive association between optimism and anxiety emergence. Contrary to our expectations, however, religious experience related to FXS predicted higher risk for MDD, and hope did not significantly relate to the presence or course of either MDD or anxiety. These findings lend insight into protective factors in women with the FMR1 premutation, as well as potential points of prevention in the emergence of psychopathology in this population.

Optimism

The finding that increased optimism predicted a decreased likelihood of initial MDD and decreased risk for anxiety over time is quite powerful considering that this study used diagnostic criteria versus screening measures, controlled for prior history of MDD and anxiety, and employed a short 3-year interval between assessments. The current findings are consistent with existing literature that has consistently demonstrated an inverse relationship between optimism and both anxiety (Bailey et al., 2008; Siddique, et al., 2006) and depression (Andersson, 1996; Bailey et al., 2008; Brisette et al., 2002; Grote et al., 2007) in individuals with and without the FMR1 premutation. This relationship is also seen in mothers raising children with a disability other than FXS (Baker et al., 2005, Ekas et al., 2010). Taken together, our study and much of the current literature suggests that optimism may confer protection against the development of anxiety and MDD. It is possible that that in times of stress, individuals high in optimism use more constructive coping strategies, such as planning, seeking support, or humor, than people who are less optimistic (Scheier et al., 1994). These strategies could be particularly relevant to women with the FMR1 premutation who may experience high levels of stress due to raising a child with a significant disability. Notably, the association between optimism and mental health is likely bidirectional and may vary across other contextual dimensions such as social support (Brisette et al., 2002). Although it is possible that the association between optimism and depression reflects overlap in these constructs, optimism distinctly predicted concurrent depression and future anxiety, rather than universally predicting both concurrent and future occurrence of both disorders, suggesting that effects of optimism may extend beyond symptoms of depression alone. However, to clarify the unique role of optimism in the course of depression and anxiety, future work may integrate experimental or treatment approaches to prospectively test the effects of manipulating optimism on mental health. With further study, integrating optimism into treatment protocols for women with the FMR1 premutation may help reduce MDD symptoms and emergent anxiety in this high-risk group.

Religious Experience in Relation to Fragile X

Contrary to our expectations, increased religious experiences related to FXS did not predict a decreased risk of anxiety or MDD. Instead, increased religious participation was associated with higher risk of MDD at Time 1 (OR=2.52), with greater magnitude than optimism (OR=0.43). This unexpected association between religious experience related to FXS and lifetime MDD may relate to the complexity of associations observed in previous studies of religiosity and well-being. For example, “positive” religious coping strategies (e.g. seeking religious support, coping with others, forgiveness) are generally associated with positive adjustment (r=.33), whereas “negative” religious coping strategies (e.g. attributing experiences to punishment from God, pleading for intercession for undesirable events) are associated with higher incidence of poorer psychological adjustment, including depression and anxiety (r=.22; Ano & Vasconcelles, 2005). It is also possible that the positive association between religion and MDD observed in our data reflects an increased attempt to engage religion as a means of coping among women with greater distress. Indeed, religions participation at Time 1 was related to lifetime MDD at Time 1 only, suggesting high religion co-occurred with MDD rather than predicted future MDD episodes. Differences between our findings and previous studies may also relate to measurement, as we specifically focused on personal religion and religious participation as related to FXS, whereas the strongest connections between religion and psychopathology in previous literature are often focused on religious coping (Bosworth et al., 2003; Smith et al., 2003). Thus, although our finding is consistent with previous reports that certain aspects of religion do not predict higher quality of life in women with the FMR1 premutation (Wheeler et al., 2008), additional work is warranted to determine whether different aspects of religion – beyond how the individual has experienced religion in relation to FXS – may affect risk and resilience.

Hope

Our finding that hope was not associated with either MDD or anxiety was somewhat inconsistent with previous studies in which hope predicted well-being in premutation samples (Bailey et al., 2008; Wheeler et al., 2008), less depressive symptomology in a sample of mothers of children with intellectual disability (Lloyd & Hastings, 2009), and decreased depressive and anxious symptomology in non-premutation samples (Arnau et al., 2007; Needles & Abramson, 1990). Differences may relate to our specific sample, use of a long follow-up period, and dichotomous diagnostic criteria. Other studies which have found relationships between hope and depression or anxiety have primarily used continuous rating scales (Chang & DeSimone, 2001; Elliott et al., 1991; Arnau et al., 2007) and much shorter follow up intervals (e.g. Needles & Abramson, 1990: 6 weeks; Arnau et al., 2007: 3 weeks), which may be more sensitive to changes over time. Thus in the current study, the effects of hope may have reduced the severity of symptomology, but not have been strong enough to completely protect the individual from the presence of psychopathology over such a long window of time. In addition, it is possible that unlike previous studies in non-premutation samples, our sample may experience unique life experiences that moderate associations between hope and psychopathology, particularly as related to parenting a child with FXS. Including measures of stress may better contextualise associations between hope and psychopathology, which may be most apparent in women with high stress.

Limitations

Though this study makes several important contributions to the literature, there are several limitations. First, although collapsing anxiety disorders into one category is adequate as an initial examination given our sample size, future research may wish to study the anxiety disorders separately. Additionally, MDD and anxiety were determined using diagnostic criteria and were characterised dichotomously, which although a strength of the study, may have prevented us from observing associations that may be more apparent when examining symptom severity. We also did not include a comparison group, precluding conclusions as to whether findings would be similar in women raising children with other disabilities, or women with the FMR1 premutation but without children with FXS. Finally, although our longitudinal design enabled us to test prospective associations between resilience and mental health, these associations are likely complex and multidirectional and thus should not be interpreted as deterministic in nature. Future work in higher-powered samples should explicitly test whether protective factors interact to buffer against psychopathology emergence.

Summary and Implications

This study is the first to use a prospective longitudinal design to examine optimism, religious experience related to FXS, and hope as potential protective factors that could minimise the presence or severity of MDD and anxiety in women with the FMR1 premutation. Results indicate that women with the FMR1 premutation who are optimistic are less likely to meet lifetime diagnostic criteria for MDD and are less likely to meet criteria for anxiety disorders over time. Increased participation in religious experiences, along with more severe child problem behaviour and age, were also associated with increased MDD. Thus, optimism appears to be an important protective characteristic in these women and could be targeted in interventions, along with behavioural training to address child problem behaviours. Such interventions could include bolstering informal support from family and community (Bailey, et al., 2007) which has been shown to increase optimism in mothers of children with disabilities.

Acknowledgments

National Institute of Mental Health

Grant numbers: F31-MH095318/ R01-MH090194

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Grant numbers: P30-HD003110-35S1

References

- Achenbach T. Manual for the child behavior checklist/4–18 and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G. The benefits of optimism: A meta-analytic review of the Life Orientation Test. Personality and Individual Differences. 1996;5:719–725. [Google Scholar]

- Ano GG, Vasconcelles EB. Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;61:461–480. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnau RC, Rosen DH, Finch JF, Rhudy JL, Fortunato VJ. Longitudinal effects of hope on depression and anxiety: A latent variable analysis. Journal of Personality. 2007;75(1):43–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB, Nelson L, Hebbeler K, Spiker D. Modeling the impact of formal and informal supports for young children with disabilities and their families. American Academy of Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e992–e1001. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB, Sideris J, Roberts J, Hatton D. Child and genetic variables associated with maternal adaptation to fragile X syndrome: A multidimensional analysis. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part A. 2008;146A:720–729. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB, Wheeler A, Berry-Kravis E, Hagerman R, Tassone F, Sideris J. Maternal consequences of the detection of fragile X carriers in newborn screening. Pediatrics. 2015;136 doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, Blacher J, Olsson MB. Preschool children with and without developmental delay: Behaviour problems, parents’ optimism and well-being. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2005;49(8):575–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois J, Seritan A, Casillas EM, Hessl D, Schneider A, Yang Y, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in fragile X premutation carriers. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2011;72:175–182. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05407blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth HB, Park KS, McQuoid DR, Hays JC, Steffens DC. The impact of religious practice and religious coping on geriatric depression. International Jounrla of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003;18(10):905–914. doi: 10.1002/gps.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brissette I, Scheier MF, Carver CS. The role of optimism in social network development, coping, and psychological adjustment during life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82(1):102–111. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish K, Kraan C, Bui Q, Bellgrove MA, Metcalfe SA, Trollor JN, et al. Novel methylation markers of the dysexecutive-psychiatric phenotype in FMR1 premutation women. Neurology. 2015;84:1631–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens EM, Kasari C. Maladaptive behavior in children with Prader-Willi syndrome, Down syndrome, and nonspecific mental retardation. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 1997;102(3):228–237. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(1997)102<0228:MBICWP>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekas NV, Lickenbrock DM, Whitman TL. Optimism, social support, and well-being in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010;40:1247–1284. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-0986-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott TR, Witty TE, Herrick S, Hoffman JT. Negotiating reality after physical loss: Hope, depression, and disability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61(4):608–613. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.4.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichter MM, Kohlboeck B, Quadflieg N. The Upper Bavarian longitudinal community study 1975–2004 Long-term course and outcome of depression. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2008;258:476–488. doi: 10.1007/s00406-008-0821-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichter MM, Quadflieg N. Three year course and outcome of mental illness in homeless men: A prospective longitudinal study based on a representative sample. European Archives of Psychiatry Clinical Neuroscience. 2005;255:111–120. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fewell RR. Supports from religious organization and personal beliefs. In: Fewell RR, Vadasy PF, editors. Families of handicapped children: Needs and supports across the life span. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 1986. pp. 297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Grote NK, Bledsoe SE, Larkin J, Lemay EP, Brown C. Stress exposure and depression in disadvantaged women: The protective effects of optimism and perceived control. Social Work Research. 2007;31(1):19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ, Berry-Kravis E, Kaufmann WE, Ono MY, Lachiewicz A, Kronk R, et al. Advances in the treatment of fragile X syndrome. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):378–390. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton DD, Hooper SR, Bailey DB, Skinner ML, Sullivan KM, Wheeler A. Problem behaviour in boys with fragile X syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2002;108:105–116. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjelle L, Belongia C, Nesser J. Psychometric properties of the life orientation test and attributional style questionnaire. Psychological Reports. 1996;78(2):507–515. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter JE, Leslie M, Novak G, Hamilton D, Shubeck L, Charen K, et al. Depression and anxiety symptoms among women who carry the FMR1 premutation: impact of raising a child with fragile X syndrome is moderated by CRHR1 polymorphisms. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric Genetics : The Official Publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics. 2012;159B:549–59. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kau AS, Tierney E, Bukelis I, Stump MH, Kates WR, Trescher WH, et al. Social behavior profile in young males with fragile X syndrome: characteristics and specificity. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part A. 2004;126A(1):9–17. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. Epidemiology of women and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2003;74:5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Shankman SA, Rose S. Dysthymic disorder and double depression: Prediction of 10-year course trajectories and outcomes. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008;42:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG. Predictors of depression outcomes in medical inpatients with chronic pulmonary disease. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):939–948. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000206380.57732.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd TJ, Hastings R. Hope as a psychological resilience factor in mothers and fathers of children with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2009;53(12):957–969. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loesch DZ, Bui MQ, Hammersley E, Schneider a, Storey E, Stimpson P, et al. Psychological status in female carriers of premutation FMR1 allele showing a complex relationship with the size of CGG expansion. Clinical Genetics. 2015;87:173–8. doi: 10.1111/cge.12347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailick M, Hong J, Greenberg J, Smith L, Sherman S. Curvilinear association of CGG repeats and age at menopause in women with FMR1 premutation expansions. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric Genetics: The Official Publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics. 2014;165:705–11. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32277.Curvilinear. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie M, Skinner D. Narrating disability, narrating religious practice: Reconciliation and fragile X syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability. 2010;48(2):99–111. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-48.2.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needles DJ, Abramson LY. Positive life events, attributional style, and hopefulness: Testing a model of recovery from depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99:156–165. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati G, Pietrantoni L. Optimism, social support, and coping strategies as factors contributing to posttraumatic growth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2009;14:364–388. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JE, Bailey DB, Mankowski J, Ford A, Sideris J, Weisenfeld LA, et al. Mood and anxiety disorders in females with the FMR1 premutation. American Journal of Medical Genetics Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2009;150B:130–139. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JE, Tonnsen BL, McCary LM, Ford AL, Golden RN, Bailey DB. Trajectory and predictors of depression and anxiety disorders in mothers with the FMR1 premutation. Biological Psychiatriy. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.07.015. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology. 1985;4:219–247. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-master, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer M, Barker E, Greenberg J. Differential sensitivity to life stress in FMR1 premutation carrier mothers of children with fragile X syndrome. Health Psychology. 2012;31:612–622. doi: 10.1037/a0026528.Differential. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddique HI, LaSalle-Ricci VH, Glass CR, Arnkoff DB, Diaz RJ. Worry, optimism, and expectations as predictors of anxiety and performance in the first year of law school. Cognitive Therapy Research. 2006;30:667–676. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner DG, Correa V, Skinner M, Bailey DB. Role of religion in the lives of Latino families of young children with developmental delays. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2001;106(4):297–313. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2001)106<0297:RORITL>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TB, McCullough ME, Poll J. Religiousness and depression: Evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(4):614–636. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR. The psychology of hope. New York: The Free Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, Holleran SA, Irving LM, Sigmon ST, Yoshinobu L, Gibb J, Langelle C, Harney P. The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60:570–585. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.60.4.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Sympson SC, Ybasco FC, Borders TF, Babyak MA, Higgins RL. Development and validation of the State Hope Scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:321–335. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone F, Iong KP, Tong T, Lo J, Gane LW, Berry-Kravis E, et al. FMR1 CGG allele size and prevalence ascertained through newborn screening in the United States. Genome Medicine. 2012;4:1000. doi: 10.1186/gm401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuorilehto M, Melartin T, Isometsa E. Depressive disorders in primary care: recurrent, chronic, and co-morbid. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:673–682. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler AC, Skinner DG, Bailey DB. Perceived quality of life in mothers of children with fragile X syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2008;113(3):159–177. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2008)113[159:PQOLIM]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. Attainment and maintenance of reliability of axis I and II disorders over the course of a longitudinal study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2001;42(5):369–374. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.24556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]