Abstract

Gastrointestinal symptoms, such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain, are very common in patients with Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE). Mild thiamine deficiency may have only gastrointestinal symptoms. We are reporting two patients with thiamine deficiency who predominantly had gastrointestinal symptoms. Case 1: a 38-year-old man had gastrointestinal problems for about 2–3 years. It gradually became severe. The patient came to the neurology outpatient department for his recent-onset vertigo and headache. Clinical examinations fulfilled Caine’s criteria of WE. Gastrointestinal symptoms responded dramatically to intravenous thiamine. Case 2: a 21-year-old woman developed drug-induced hepatitis and gastritis. Associated nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain progressively increased over the weeks. The patient responded only to intravenous thiamine administration.

We suggest that a suspicion for gastrointestinal beriberi should arise if gastrointestinal symptoms (anorexia, nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain) are refractory to the usual therapies.

Keywords: vitamins and supplements, medical management, neurogastroenterology

Background

Thiamine deficiency classically presents as Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE), dry beriberi and wet beriberi.1 Gastrointestinal symptoms, such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting and pain in the abdomen, are often described in patients with WE and beriberi.2 However, a few patients may have predominantly gastrointestinal manifestation. Donnino coined ‘Gastrointestinal beriberi’ for such patients.3 Surprisingly, nausea and vomiting are also the risk factors for the development of WE. Herein, we report two cases of thiamine deficiency who predominantly had gastrointestinal symptoms.

Case presentation

Case 1

A 38-year-old man had a variable abdominal discomfort for about 2–3 years. Abdominal discomfort was noted mainly in the form of abdominal fullness, indigestion, abdominal pain, nausea and decreased appetite. The pain was pressing type and mainly localised to the epigastrium. The abdominal fullness and pain used to worsen after eating. The problems were initially intermittent with a frequency of one to two attacks in a week. However, for the last 7–8 months, it had been a regular event and the patient noted these symptoms almost daily. He also noted increasing constipation for the last few months. However, he did not find any significant improvement in the abdominal discomfort with defecation. Occasionally, he also had mild vomiting. However, he denied any haematemesis. His eating habits were not regular and he would skip meals several days in a month for religious and other reasons. He lost 4–5 kg weight over a few months. There was no history of alcohol intake or any substance abuse.

The patient visited a number of gastroenterologists. However, no abnormality was noted in physical examinations and investigations. The investigations included complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, blood glucose, liver function tests, kidney function tests, thyroid profiles, stool tests, ultrasound of the gallbladder, abdominal CT scan and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. The patient received a number of provisional diagnoses over 2–3 years: irritable bowel syndrome, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, peptic ulcer disease, food allergies, parasitic infections, coeliac disease and so on. However, he did not get any notable improvement by any treatment. Later on, his symptoms were thought to be psychosomatic in nature and he had been advised anti-anxiety medications and antidepressants. However, only mild and transient improvement was noted with this regime.

The patient consulted to the neurology outpatient department for his recent-onset headache and vertigo (spinning sensation) over the last 3–4 weeks. The headache was mild, holocephalic and pressing type. The vertigo was both spontaneous and induced (by neck turning or body movement). An episode of vertigo used to last for a few hours. Vertigo was mild and did not hamper any of his routine activities. Mild to moderate headache was present in about one-third of the vertigo episodes. On inquiry, he also confirmed the presence of disturbed sleep and easy fatigability for the last 4 weeks. His gastrointestinal symptoms had also increased over 4 weeks with more frequent nausea, abdominal pain, abdominal fullness and vomiting.

Physical and neurological examinations revealed impaired Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) −27 (impaired serial sevens), gaze-evoked nystagmus, impaired finger nose testing and impaired tandem walk. Hallpike’s manoeuvre and caloric test were negative The patient fulfilled Caine’s criteria of WE. Intravenous thiamine (500 mg/8 hourly) was started immediately, and the patient was subjected to various investigations. No other drugs were started. MRI of the brain did not show any abnormality. Whole-blood thiamine was low (14.6 ng/mL) (normal range 25–75 ng/mL).

Case 2

A 21-year-old woman had been advised antitubercular drugs (ATDs) for pulmonary tuberculosis. She had been receiving isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol. After 1–2 weeks of initiation of ATD, the patient noted anorexia, epigastric discomfort and nausea. Initially, the symptoms were mild and intermittent. However, the symptoms gradually progressed. The pain became more diffuse, involving the whole abdomen. In parallel, nausea also became severe and persistent. She visited the medicine department for these problems. Physical examinations were largely unremarkable, except mild epigastric tenderness. Biochemical parameters revealed leucocytosis (white blood cell count 12 300 mm3), raised alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (146 U/L), raised aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (178 U/L) and elevated total bilirubin (1.4 mg/dL). A diagnosis of drug-induced hepatitis and gastritis was made. Gastroenterologist consultation was taken. Initially, modified ATD (only isoniazid and rifampicin) was advised. However, nausea and vomiting continued, and later on, all ATDs were discontinued. Gastric protective agent (oral pantoprazole) and antiemetic agent (oral ondansetron) were started. However, her symptoms did not improve and continued to have gastrointestinal problems. In fact, her symptoms worsened after 6–7 days. Abdominal pain became more severe and persistent. Nausea was severe and persistent and she started to have vomiting. The patient required hospitalisation. Repeat biochemical parameters (after 8 days) revealed decreasing ALT (124 U/L), decreasing AST (128 U/L) and improving serum bilirubin level (1.2 mg/dL). Serological testing for hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, hepatitis E virus and HIV were negative. Ultrasound of the gallbladder and abdominal CT scan were normal. The patient was treated with intravenous fluids, injectable pantoprazole, injectable ondansetron and other supportive measures. However, there was not much improvement in these treatment modalities. In addition, the patient developed (after 1 week of hospitalisation) slurring of speech and vertigo. At this point, a neurological consultation was sought.

We noted impaired MMSE (impaired serial sevens and impaired recall), gaze-evoked nystagmus, abnormal finger nose testing and gait ataxia. There was no history of alcohol intake or any substance abuse. Physical examinations suggested a possibility of WE. Injection thiamine was started immediately in a similar regimen as with the previous case (500 mg intravenously 8 hourly), and the patient was subjected to various investigations. MRI brain revealed no abnormality. Cerebrospinal fluid examinations were normal. Whole-blood thiamine was low (13.4 ng/mL).

Outcome and follow-up

Case 1: There was a complete improvement in the headache and vertigo in 24 hours. Neurological abnormalities (impaired MMSE, nystagmus, abnormal finger nose testing and abnormal tandem walk) also returned to normal in 3 days. Surprisingly, his gastrointestinal symptoms also subsided completely in 2–3 days. Injectable thiamine was given for 4 days. The patient never felt such improvement with any drug in the past. Thereafter, the patient was discharged with advice to take oral thiamine (100 mg three times daily). The patient continued oral thiamine for 4 months. The patient was followed for another 6 months. No gastrointestinal symptom was noted in that period.

Case 2: Nausea and vomiting stopped in 12 hours. Pain in the abdomen and abdominal fullness also subsided completely in 24 hours. Dysarthria, vertigo and gait ataxia improved markedly in 48 hours. The patient also noted a marked improvement in the neurological symptom (dysarthria, vertigo and gait ataxia) in 24 hours. MMSE returned to normal on the fourth day. Thiamine was continued at the same dose (500 mg intravenously 8 hourly) for a total of 5 days. Thereafter, oral thiamine (100 mg thrice daily) was advised. There was a further decrease in serum ALT (56 U/L), decreasing AST (70 U/L) and serum bilirubin levels (1.0 mg/dL). Antitubercular drugs were started again. Oral thiamine was continued with antitubercular drugs for 6 months. Follow-up was uneventful.

Discussion

A diagnosis of WE is made according to Caine’s criteria.4 Two of the following features are required for the diagnosis: (1) a history of dietary deficiencies, (2) cognitive impairment, (3) ocular abnormality and (4) cerebellar dysfunctions. Although both patients had predominantly gastrointestinal symptoms, they fulfilled the criteria of WE, as all four features of Caine’s criteria were noted in both patients. Serum thiamine levels were also low in both cases. An immediate response to injectable thiamine in both cases further reinforces the diagnosis of thiamine deficiency or WE. Gastrointestinal symptoms also subsided with intravenous thiamine.

WE is typically described in alcoholic patients. However, there are several clinical settings on which WE and other features of thiamine deficiency may develop. The body’s thiamine reserves are very limited and can be depleted in as little as 2–3 weeks.1 Therefore, unbalanced nutrition of 2–3 weeks may lead to WE. In a person with marginal stores of thiamine, WE may occur early. Moreover, various comorbid medical conditions may further enhance the thiamine loss.1

WE is typically considered as a neurological disorder. Gastrointestinal symptoms are not part of the criteria of WE. Several case series have just focused on the neurological symptoms of WE and have not mentioned anything about gastrointestinal symptoms.5 On the contrary, various large case series reported gastrointestinal symptoms as a universal phenomenon in patients with WE. De Wardener and Lennox reported 52 cases of WE.6 They write, “Loss of appetite was the first symptom and was present in all cases in which a history could be taken. Nausea would follow, and then vomiting”. Recently, Shah et al reported 50 cases of non-alcoholic WE. About 90% patients had preceding or concomitant recurrent vomiting and nausea.7 In the 1940s, Williams and colleagues studied the effects of depletion of thiamine from diets in healthy individuals. Almost all participants noted nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain.8 However, none of the participants developed classical WE and beriberi.

Literature is limited about the prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with thiamine deficiency. However, based on the review of the literature, we presume that gastrointestinal symptoms may not be uncommon in patients with thiamine deficiency. However, it is not clear whether gastrointestinal beriberi is part of WE or it is a separate disease entity like dry or wet beriberi.

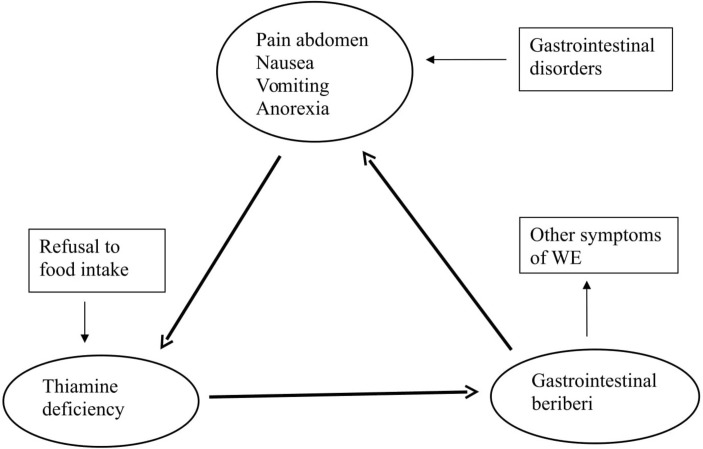

Interrelation between thiamine, gastrointestinal symptoms and WE

Anorexia, nausea, vomiting and pain in the abdomen are the common features of several gastrointestinal disorders. All these features are risk factors for thiamine deficiency.1 Therefore, the low thiamine level would further exacerbate anorexia, nausea, vomiting and pain in the abdomen. So, it can be speculated that abdominal symptoms could be both cause and effects in thiamine deficiency (WE). Therefore, a vicious circle can be formed where anorexia, nausea and vomiting will be aggravated because of the decreasing thiamine levels, independent of the primary disease entity (figure 1). Nausea and vomiting may beget nausea and vomiting. Anorexia, nausea, vomiting and pain in the abdomen may persist even if the primary disease subsided completely. In case 2, patient’s early gastrointestinal symptoms were probably related to drug-induced hepatitis and gastritis. Drug-induced anorexia and vomiting led to a deficiency of thiamine, which in a cyclical pattern aggravated the gastrointestinal symptoms. The cycle could be terminated only by the intravenous thiamine.

Figure 1.

Possible interrelation between gastrointestinal disorders, gastrointestinal beriberi and Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE).

This cycle may start even with poor food habits (irregular meals or by taking staple diet meals) or voluntarily refusal of foods. Various studies have demonstrated increased gastrointestinal symptoms because of the frequent fasting for religious and other reasons.9 Various assumptions have been proposed for such gastrointestinal symptoms. However, as thiamine depletes easily by unbalanced nutrition, we speculate that a large number of such symptoms may be because of thiamine deficiency. Several times such patients receive thiamine supplementation unknowingly (foods or by over-the-counter vitamins). Such supplementation may or may not be enough to restore thiamine deficiency. Therefore, patients may get fluctuating or recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms. Poor eating habits (irregular meals) may be the reason for the thiamine deficiency in case 1.

Thomson et al, after a review of the literature, suggested that anorexia, nausea and vomiting may be the early feature of thiamine deficiency (before the development of WE).2 Chronic suboptimal thiamine intake may lead to mild to moderate gastrointestinal symptoms for a protracted period. However, it may turn into more severe WE if thiamine deficiency becomes more severe. Once vomiting starts, it will be difficult to supplement thiamine orally. Vomiting may not respond to usual antiemetics and the patient may develop full-blown WE.

Diagnostic considerations

A diagnosis of thiamine deficiency is easily missed, even in patients with classical WE. A diagnosis of WE is missed in 75%–80% of patients with alcoholism and 94% of patients without alcoholism.1 10 11 Therefore, mild WE or non-specific symptoms related to thiamine deficiency could be easily unnoticed.10 11 Moreover, thiamine deficiency may develop over a number of pre-existing diseases. So, it becomes very difficult to diagnose thiamine deficiency over a pre-existing disease. Sechi and Serra noted more than 100 clinical settings for the development of WE.1 Gastrointestinal disorders are one of the common risk factors for thiamine deficiency. Gastrointestinal beriberi may mimic pre-existing gastrointestinal disorders. So, it will be very difficult to identify gastrointestinal beriberi in patients with pre-existing gastrointestinal disorders.

Our case reports and review of the literature suggest that pure gastrointestinal beriberi mainly results from the unbalanced nutrition. It may have protracted course if unbalanced nutrition persists for a longer period. Therefore, gastrointestinal beriberi may as isolated phenomenon because of thiamine deficiency. However, gastrointestinal beriberi may turn into WE if it is not recognised or treated in the early stage. In this circumstance, abdominal symptoms can be labelled as early symptoms of WE. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal beriberi is important as treatment is very simple, and it prevents the patients from being subjected to various unnecessary investigations and therapeutic trials. Moreover, life-threatening WE can be prevented or treated in the very early stage.

There is a general consensus among experts that thiamine should be administered without delay on the suspicion of WE or thiamine deficiency.1 10 It has been demonstrated that oral thiamine is ineffective in increasing blood thiamine level and curing WE.10 Therefore, injectable thiamine is recommended in the early stage of treatment. However, there is no consensus on the optimal dose of thiamine. A few authors suggest a very high doses (500 mg 8 hourly) in the early few days.1 A dramatic response is highly suggestive of WE or thiamine deficiency. Supplementation can be discontinued if there is no response in 2–3 days.1

Thiamine deficiency leads to brain changes (mainly congestion and haemorrhages). It is mainly localised in the periaqueductal grey matter, around the third and fourth ventricles, the mammillary bodies and medial thalamus. The lesions may extend to involve superior vermis, the pontine tegmentum, the posterior corpora quadrigemina, hypothalamus and the cerebral cortex.1 12

Thiamine is converted to thiamine pyrophosphate in neuronal and glial cells. Thiamine pyrophosphate acts in several biochemical pathways in the brain, such as intermediate carbohydrate metabolism (for ATP synthesis), lipid metabolism (helps in myelin sheath production) and production of amino acids and glucose-derived neurotransmitters. Thiamine also have a role in acetylcholinergic and serotoninergic synaptic transmission. Transketolase activity is first to reduce after thiamine deficiency. It will lead to a number of pathophysiological processes. These include alterations in acetylcholine synthesis, abnormal glucose metabolism, oxidative stress, lactic acidosis and mitochondrial dysfunctions, inflammatory activation and glutamate N-Methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-receptor-mediated toxicity. This will lead to cell damage.12

Both cases were seen in the neurology department when they developed some non-specific neurological symptoms. However, it is more likely that patients with gastrointestinal beriberi will visit the medicine or gastroenterology outpatient department. Therefore, physicians working in such clinics should be aware of gastrointestinal beriberi.

Limitations

These are just two cases; therefore, findings noted here cannot be generalised. A possibility of recall bias also exists in our patients. Both patients fulfilled Caine’s criteria of WE and also had a low thiamine level. However, we cannot rule out the possibility of other secondary causes for the patients’ current symptoms as full investigations were not done. Investigations for gastrointestinal symptoms were not complete. MRI brain was normal in both patients. The presence of MRI abnormality typical of WE could have been more reinforcing. However, the sensitivity of MRI is low (53%) even with classical WE.1 Mild WE and predominantly gastrointestinal beriberi may have normal neuroimaging. A dramatic response to thiamine in both cases suggests thiamine deficiency. However, a possibility of placebo response cannot be ruled out here.

Conclusion

The body’s reserves for thiamine is limited. It gets depleted very fast. Moreover, a large number of clinical syndromes may lead to thiamine deficiency. Mild to moderate thiamine deficiency may lead to gastrointestinal beriberi. Gastrointestinal beriberi may further lower the thiamine level and the patient may develop full-blown WE. If any patient with a history of any pre-existing disease and/or unbalanced nutrition develops gastrointestinal symptoms, a possibility of gastrointestinal beriberi should be suspected. Thiamine can be given empirically. An immediate response may favour the diagnosis. It is hoped that these cases and our speculation on the inter-relation between thiamine and gastrointestinal symptoms may serve as a catalyst for further studies to clarify the issue.

Learning points.

Mild thiamine deficiency may lead to anorexia, nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain.

Gastrointestinal beriberi may have a protracted course or may turn rapidly into classical Wernicke’s encephalopathy.

Gastrointestinal beriberi may further lower the thiamine intake or thiamine level into a cyclical pattern.

Immediate improvement in the symptoms may be noted by thiamine supplementation.

Footnotes

Contributors: SP was involved in the conception and design of the study. He was involved in the acquisition of data, manuscript preparation and revising the draft for intellectual content. The author approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The author has not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study does not require approval by the Institute Ethics Committee as per the local regulations for case reports.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Sechi G, Serra A. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:442–55. 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70104-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomson AD, Cook CC, Guerrini I, et al. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: ’Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose'. Alcohol Alcohol 2008;43:180–6. 10.1093/alcalc/agm149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donnino M. Gastrointestinal beriberi: a previously unrecognized syndrome. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:898–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caine D, Halliday GM, Kril JJ, et al. Operational criteria for the classification of chronic alcoholics: identification of Wernicke’s encephalopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997;62:51–60. 10.1136/jnnp.62.1.51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harper CG, Giles M, Finlay-Jones R. Clinical signs in the Wernicke-Korsakoff complex: a retrospective analysis of 131 cases diagnosed at necropsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1986;49:341–5. 10.1136/jnnp.49.4.341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Wardener HE, Lennox B. Cerebral beriberi (Wernicke’s encephalopathy); review of 52 cases in a Singapore prisoner-of-war hospital. Lancet 1947;1:11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah IA, Asimi RP, Kawoos Y, et al. Nonalcoholic wernicke’s encephalopathy: a retrospective study from a tertiary care center in northern India. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2017;8:401–6. 10.4103/jnrp.jnrp_14_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams RD, et al. Observations on induced thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency in man. Arch Intern Med 1940;66:785–99. 10.1001/archinte.1940.00190160002001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadeghpour S, Keshteli AH, Daneshpajouhnejad P, et al. Ramadan fasting and digestive disorders: SEPAHAN systematic review no. 7. J Res Med Sci 2012;17:S150–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galvin R, Bråthen G, Ivashynka A, et al. EFNS guidelines for diagnosis, therapy and prevention of Wernicke encephalopathy. Eur J Neurol 2010;17:1408–18. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03153.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prakash S, Kumar Singh A, Rathore C. Chronic migraine responding to intravenous thiamine: a report of two cases. Headache 2016;56:1204–9. 10.1111/head.12838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson GE, Blass JP. Thiamine-dependent processes and treatment strategies in neurodegeneration. Antioxid Redox Signal 2007;9:1605–20. 10.1089/ars.2007.1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]