Abstract

The majority of natal and neonatal teeth are prematurely erupted primary teeth, whereas few are supernumerary in origin. They most commonly occur in mandibular central incisor region and often can lead to difficulty to the mother during breast feeding and tongue ulceration in newborn. Moreover, since majority of these have poorly developed roots and are mobile, there is always a fear of aspiration into respiratory passage. Extraction therefore is the most commonly rendered treatment for these teeth. This paper comprises cases of natal and neonatal teeth describing about their clinical characteristics and sequel. This paper has also highlighted the factor which needs to be considered during the management of natal/neonatal teeth and protocol followed at our centre.

Keywords: congenital disorders, neonatal health

Background

Natal teeth are present at birth, whereas neonatal teeth erupt in first 30 days of life. Natal teeth are three times more common compared with neonatal teeth.1 Their incidence is rare, ranging from 1:2000 to 1:3500.2 3 Majority of them are prematurely erupted primary teeth and only less than 10% are known to be supernumerary by origin.4 5 A prematurely erupted primary tooth can be easily differentiated from a supernumerary tooth with the help of radiograph usually indicated at the time of eruption of the primary tooth.6 Although, there is no gender predilection, however, a slightly higher prevalence has been cited in female by some authors.7 They most commonly occur in mandibular central incisor region followed by the maxillary incisors.8 Although, trauma, infection, malnutrition, hormonal stimulation, superficially placed tooth germ and maternal exposure to environmental toxins have been implicated as an aetiologic factor, the exact aetiology of the condition still remains unknown.9 These natal/neonatal teeth often can lead to difficulties like pain to mother during breast feeding, tongue ulcerations and refusal to feed in newborn and risk of aspiration. The decision to extract is based on associated local and/or general complications, tooth prognosis and parental opinion.10

Case presentation

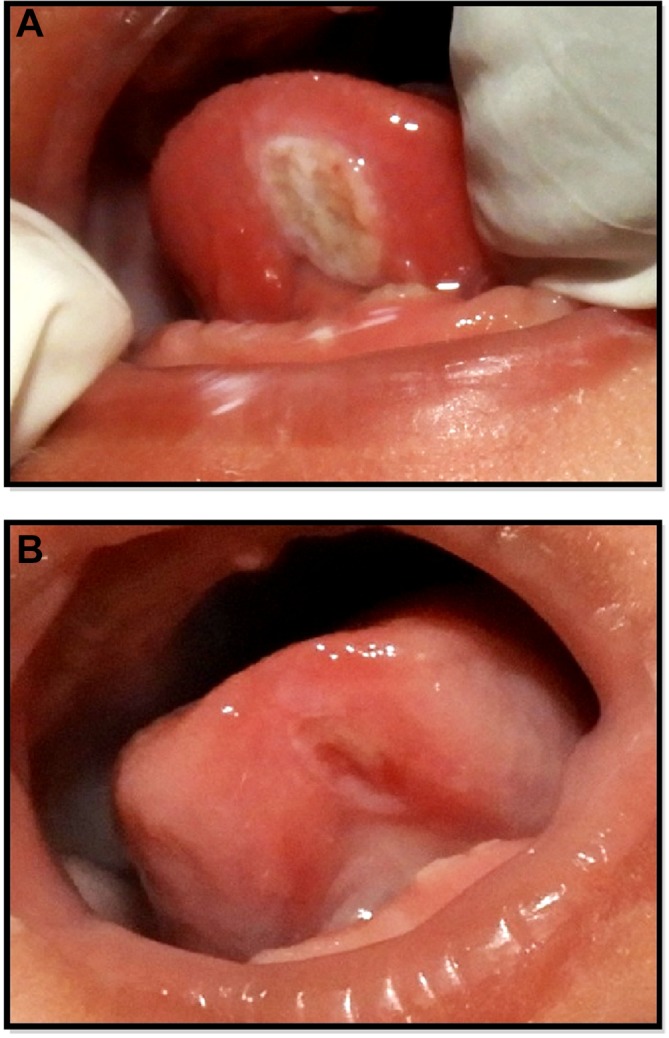

This paper comprises seven cases who reported to the Unit of Paediatric dentistry with premature eruption of teeth in oral cavity. History revealed two of these to be erupted at birth (natal teeth), whereas other five had erupted in the first month of life (neonatal teeth). Associated anomalies/syndromes were not present in any of these children except one child who was born prematurely in 34 weeks. In six out of seven cases, teeth were mobile in nature and mothers were experiencing difficulty during breast feeding, whereas in remaining one case although tooth was firm, it was leading to ulceration on ventral surface of tongue (figure 1A). Table 1 explains the demographic information of children and the characteristics of natal and neonatal teeth which were classified based on their clinical characteristics (Hebling classification 1997 (table 2)).

Figure 1.

(A) Ulceration on ventral surface of tongue as a complication of neonatal tooth. (B) Resolution of ulceration after grinding of incisal edges of neonatal tooth.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of newborns

| Case | Age | Sex | Time of tooth appearance | Associated problems | Tongue ulceration | Medical condition associate | Classification (Hebling 1997) |

Administered with prophylactic vitamin K at birth | Treatment rendered | Tooth origin (supernumerary/ pre-erupted deciduous teeth) |

Follow-up period (months) |

| Case 1 | 29 days | F | 12 days | Mobility and difficulty in feeding | Absent | Premature birth 7.5 months |

2 | Yes | Extraction | Pre-erupted deciduous teeth |

20 months |

| Case 2 | 1½ months | M | 5 days | Mobility | Absent | None | 2 | Yes | Extraction | – | – |

| Case 3 | 1 month | F | 15 days | Mobility | Absent | None | 2 | Yes | Extraction | Pre-erupted deciduous teeth |

15 months |

| Case 4 | 1 month 5 days | M | 10 days | Difficulty in feeding | Present | None | 2 | Yes | Grinding of incisal edges of tooth | Pre-erupted deciduous teeth |

12 months |

| Case 5 | 18 days | M | Birth | Mobility and difficulty in feeding | Absent | None | 1 | No | Extraction | Pre-erupted deciduous teeth |

24 months |

| Case 6 | 7 days | F | Birth | Mobility and difficulty in feeding | Absent | None | 1 | Yes | Extraction | Pre-erupted deciduous teeth |

18 months |

| Case 7 | 25 days | M | 21 days | Mobility and difficulty in feeding | Absent | None | 2 | No | Extraction | Pre-erupted deciduous teeth |

24 months |

Table 2.

Hebling classification of natal/neonatal teeth (1997)

| Type | Clinical description |

| Class 1 | Shell-shaped crown poorly fixed to alveolus by gingival tissue and absence of a root |

| Class 2 | Solid crown poorly fixed to the alveolus by gingival tissue and little or no root |

| Class 3 | Eruption of the incisal margin of the crown through gingival tissue |

| Class 4 | Oedema of gingival tissue with an unerupted but palpable tooth |

Treatment

In order to avoid feeding difficulty and prevent an accidental aspiration into the respiratory passage, extractions of mobile teeth were planned (figure 2A,B), whereas a significant improvement was seen in tongue ulceration following grinding of incisal edges of non-mobile tooth (figure 1B). Extractions of mobile teeth were performed under topical anaesthetic gel (2% lignocaine) with the help of gauze. Five out of these seven children were born at Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, and had been administered with prophylactic vitamin k at birth. Two children were referred from other centres and prophylactic vitamin K had not been administered in them till the time of presentation. Vitamin K (1 mg) was administered prior to extraction in cases where prophylactic dose was not been given immediately after birth.

Figure 2.

(A) Clinical photograph of 18 days infant with natal teeth in mandibular anterior region. (B) Extracted mandibular anterior teeth.

Outcome and follow-up

All the cases were recalled for follow-up examination and were assessed clinically and radiographically. Follow-up radiograph differentiated a supernumerary tooth from an early erupted primary tooth (figure 3A,B). The absence of corresponding primary tooth in six out of seven cases during recall examination revealed that natal/neonatal teeth were prematurely erupted primary teeth. One case did not report for recall visit. Counselling was provided to all the parents to reduce their fear due to beliefs and misconceptions.

Figure 3.

(A) Clinically missing primary mandibular central incisors after 2 years of follow-up (B) Two years follow-up radiograph with missing primary mandibular central incisors.

Discussion

Management of natal/neonatal teeth is governed by many factors including tooth prognosis, risk of aspiration, difficulty in breast feeding, risk of haemorrhage and beliefs/misconceptions which should be taken into consideration in treatment planning.

Preoperative evaluation of teeth is important to assess their development, root formation, mobility and hence the risk of aspiration. It is also very essential to rule out difficulty in feeding to mother or in a child due to tongue ulcerations. The decision to extract a natal or neonatal tooth should be weighted depending on complications associated with it against the loss of space and mesial drifting of permanent tooth leading to crowding in permanent dentition. Aesthetic concern is another limiting factor that guides the conservative management of premature primary teeth as child would remain without teeth till eruption of corresponding permanent teeth. Grinding or smoothening of incisal edges can be an alternative to extraction to prevent complications associated with these teeth. Covering the incisal portion with composite resin could also serve the purpose.11

Six cases included in this paper were associated with mobility and a subsequent risk of aspiration leaving extraction as an only treatment option, whereas one case managed conservatively with grinding of incisal edges of offending tooth. Clinical problems associated with natal/neonatal tooth, therefore, many a times make an extraction mandatory. However, in such a situation, where an extraction is indicated, it is safer to wait till child become 10 days old. A newborn cannot produce vitamin K at birth and this waiting period of 10 days before tooth extraction helps to establish intestinal commensal flora that synthesise vitamin K. It is required for the production of prothombin in liver and coagulation of blood.12 13 There may be cases where due to difficulty in feeding, trauma or risk of aspiration, it is not advisable to wait and extractions should be carried out as soon as possible to prevent the complications. In such a scenario, it is advisable to consult a paediatrician/neonatologist prior to extraction to evaluate the need for vitamin K administration. If a child has not been given vitamin K prophylaxis at birth, a dose (0.5–1.0 mg) should be given intramuscularly.14 Two of seven cases presented in this case series were administered with vitamin K (1 mg) before extraction after consulting with a paediatrician, whereas remaining five cases already had vitamin K prophylaxis immediately after birth.

An association also has been reported between premature teeth in newborns and certain syndromes. The commonly associated syndromes include Ellis-Van Creveld syndrome (chondroectodermal dysplasia),15 Hallermann-Streiff (oculomandibulodyscephaly with hypotrichosis),16 Rubinstein-Taybi, Pierre-Robin, cleft lip and palate, ectodermal dysplasia, craniofacial dysostosis.17 Although, none of the child included in this case series was syndromic, a thorough systemic evaluation is very essential in children with premature tooth eruption.

The fact cannot be denied that premature eruption of teeth in mouth of a newborn is associated with lot of superstitions. Often, the affected child may become deprived of love and affection from parents. The families are so concerned that they want premature tooth to be removed as early as possible. Therefore, along with the management of natal/neonatal teeth, psychological counselling of the parents is also very important.

Learning points.

The presence of natal/neonatal teeth though is uncommon in newborn; often they can be associated with clinical problems and psychological trauma.

A comprehensive diagnosis, treatment planning and parental counselling with due consideration to child physiology is required for management of these teeth.

Footnotes

Contributors: MR was involved in intervention and patient care. AK was involved in intervention/performing the surgery. AG involved in planning the treatment. All authors were involved in the writing of the case report.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Mhaske S, Yuwanati MB, Mhaske A, et al. Natal and neonatal teeth: an overview of the literature. ISRN Pediatr 2013;2013:1–11. 10.1155/2013/956269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El Khatib K, Abouchadi A, Nassih M, et al. [Natal teeth: apropos of five cases]. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac 2005;106:325–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyment H, Anderson R, Humphrey J, et al. Residual neonatal teeth: a case report. J Can Dent Assoc 2005;71:394–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunha RF, Boer FA, Torriani DD, et al. Natal and neonatal teeth: review of the literature. Pediatr Dent 2001;23:158–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Primo LG, Alves AC, Pomarico I, et al. Interruption of breast feeding caused by the presence of neonatal teeth. Braz Dent J 1995;6:137–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sureshkumar R, McAulay AH. Natal and neonatal teeth. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2002;87:227F–227. 10.1136/fn.87.3.F227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anegundi RT, Sudha R, Kaveri H, et al. Natal and neonatal teeth: a report of four cases. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 2002;20:86–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King NM, Lee AM. Prematurely erupted teeth in newborn infants. J Pediatr 1989;114:807–9. 10.1016/S0022-3476(89)80142-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung AK, Robson WL. Natal teeth: a review. J Natl Med Assoc 2006;98:226–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hebling J, Zuanon AC, Vianna DR. Dente Natal—a case of natal teeth. Odontologia Clinica 1997;7:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goho C. Neonatal sublingual traumatic ulceration (Riga-Fede disease): reports of cases. ASDC J Dent Child 1996;63:362–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rusmah M. Natal and neonatal teeth: a clinical and histological study. J Clin Pediatr Dent 1991;15:251–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allwright WC. Natal and neonatal teeth. British Dent J 1958;105:163–72. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryba GE, KRAMER IR. Continued growth of human dentine papillae following removal of the crowns of partly formed deciduous teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1962;15:867–75. 10.1016/0030-4220(62)90339-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiss H, Crosett AD. Chondroectodermal dysplasia; report of a case and review of the literature. J Pediatr 1955;46:268–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robotta P, Schafer E. Hallermann-Streiff syndrome: case report and literature review. Quintessence Int 2011;42:331–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ndiokwelu E, Adimora GN, Ibeziako N. Neonatal teeth association with Down’s syndrome. A case report. Odontostomatol Trop 2004;27:4–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]