Abstract

An adolescent, right hand-dominant, baseball pitcher presented to sports medicine clinic with posterolateral right elbow pain over 4 months. He rated his pain as 8/10 with pitching, especially at the late cocking phase of throwing. Prior to consult, he had rested 3 months from pitching, progressing to strengthening exercises, with no pain relief. On physical examination, he had 120° of active external rotation, 80° of active internal rotation, mild tenderness to palpation over the capitellum and normal elbow radiography. Magnetic resonance arthrogram of the right elbow revealed subtle, posterolateral joint capsular tear and adjacent synovial hypertrophy. The patient was diagnosed with elbow synovial fold syndrome that was causing impingement at the radiocapitellar joint and was referred to an orthopaedic surgeon. Arthroscopy revealed redundant tissue; scar formation at the radiocapitellar joint was debrided. The patient participated in physical therapy for 2 months and was able to start throwing 3 months later.

Keywords: sports and exercise medicine, orthopaedics

Background

This case is important because it shows how a rare condition called elbow synovial fold syndrome (ESFS) can present, be diagnosed and be treated. ESFS is thought to result from repetitive impingement of redundant synovial folds, causing inflammation secondary to cytokine-mediated factors.1 ESFS may also be referred to as plica syndrome of the elbow. Plicae are folds of synovial membrane thought to be remnants of embryonic connective tissue that failed to fully resorb during fetal development.2 Plicae are present in 80% of the population, but are usually asymptomatic. The function of plicae is unknown, although some postulate that they act as stabilisers to prevent excessive movement. Plicae may also help distribute synovial fluid throughout the joint. Another theory is that the rich innervation in plicae helps play a role in nociception, proprioception and coordination.2 In the elbow joint, a synovial radiohumeral plica is physiologic. Plicae only become pathologic in cases where they hypertrophy and dislocate into the radiohumeral articulation, causing pain.3

Inflammation due to repeated impingement usually results from repetitive hyperextension of the joint, blunt trauma, fat pad irritation, internal elbow derangement and overloading. As a plica enlarges due to inflammation, it can be compressed between articular surfaces during elbow flexion and extension, resulting in a ‘snapping’ sensation at the joint at around 80°–100° of elbow flexion.1–3

Case presentation

We report the case of an adolescent, right hand-dominant, baseball pitcher, who presented with gradual onset of posterolateral right elbow pain over 4 months. He had MRI of his elbow 3 months prior to consult, which was read as ‘normal’. His pain was rated at 8/10 with pitching, especially at the late cocking phase of throwing. At rest, he rated his pain as 2/10. Prior to consult, he attempted to rest his elbow from pitching over 3 months, progressing to strengthening exercises over the last month with no relief from his pain.

On physical examination of his right shoulder, the patient had 120° of active external rotation and 80° of active internal rotation while supine. His right elbow had full range of motion in all planes of motion. There were no signs of focal atrophy or deficits. Elbow valgus stress test was negative, and there was no tenderness to palpation over the lateral epicondyle and distal triceps brachii tendon. Mild tenderness to palpation was noted over the capitellum.

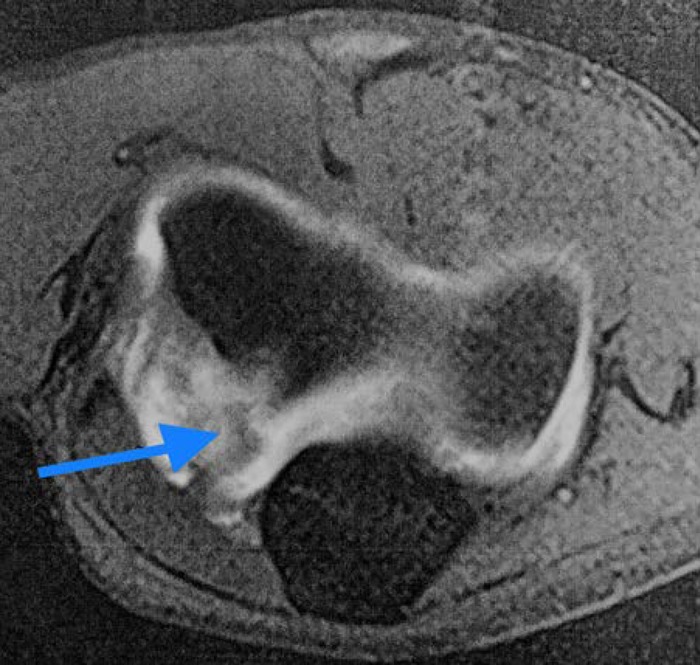

X-rays of both his elbows were normal. Magnetic resonance arthrogram (MRA) of the right elbow revealed a subtle, posterolateral joint capsular tear and adjacent synovial hypertrophy (figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Synovial proliferation noted on MRI arthrogram.

Figure 2.

Synovial fold hypertrophy noted on MRI arthrogram.

The patient was diagnosed as having ESFS, which was causing impingement at the radiocapitellar joint. He was referred to an orthopaedic surgeon. Arthroscopy revealed no osteophytes or loose bodies. Redundant tissue and scar formation at the radiocapitellar joint was noted and debrided.

Differential diagnosis

Lateral epicondylosis, loose bodies, osteoarthritis, snapping triceps tendon, radial tunnel syndrome.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient participated in the physical therapy for 2 months with no pain and was able to start a throwing programme 3 months later. He was able to fully return to baseball, pitching with no recurrence of his symptoms.

Discussion

In embryonic development, the elbow joint forms by mesenchymal cavitation sequentially at the radiohumeral site, ulnohumeral region and ending at the radioulnar site. Thereafter, all three cavities merge. The plicae are septal remnants of this process.2

Radiohumeral synovial plicae occur on the medial side of the annular ligament (figure 3). Although they are contiguous with the radiocapitellar joint capsule, they are still distinct from the annular ligament. The elbow synovial plicae are located at the radiohumeral joint and encompass the peripheral margins of the radial dome.2

Figure 3.

Frontal diagram of radiohumeral joint shows normal ‘pseudomeniscoid’ appearance of lateral radiohumeral fold (LF), located between capitellum (C) and edge of fovea radialis, fixed to capsule above superior edge of annular ligament (AL). Adapted from Cerezal et al.2 Used with permission.

There are four aspects of the radiohumeral synovial fold clearly differentiated by location (figures 4 and 5). The posterolateral synovial fold is the most common (86%–100%), located between the lower sigmoid cavity of the ulna, the radial head and the transverse sulcus of the major sigmoid cavity.2 The anterior fold (67% of cases) is a thin anterior part of the radiohumeral fold. The lateral olecranon fold originates from the posterolateral fold and travels proximally along the olecranon’s lateral periphery, with its rounded apex located at the peak of the lateral non-articular portion of the trochlear notch. The lateral fold is a horizontal meniscoid fold in the radiohumeral joint, lying between the capitellum and the outer perimeter of the radial dome.2

Figure 4.

Cadaveric dissection images show normal radiohumeral synovial fold (circular-type fold). AF, anterior fold; C, capitellum; LF, lateral fold; O, olecranon; PF, posterolateral fold; RH, radial head. Adapted from Cerezal et al.2 Used with permission.

Figure 5.

Anatomy of radiohumeral synovial fold. Diagram of elbow joint laterally opened shows normal appearance of elbow synovial plicae (circular-type fold). AF, anterior fold; LF, lateral fold; OF, lateral olecranon fold; PF, posterolateral fold; RH, radial head. Adapted from Cerezal et al.2 Used with permission.

The synovial fold is composed primarily of fibroadipose tissue and considerable amounts of nerve endings in the periphery, along with moderate vascularisation. The differentiating trait between the fold and a meniscus is the lack of fibrocartilage.2

Clinical symptoms of ESFS include motion-dependent pain in the elbow joint area and a snapping sensation with elbow flexion. Reduced range of motion, erythema and swelling may also be present. Patients are usually involved in sports requiring repetitive motions of the elbow (eg, tennis, baseball, cheerleading, golf, weightlifting). Although radiographs are not useful in diagnosis, they are still usually the initial imaging study ordered.4

Although ESFS is possible to diagnose clinically, high-resolution ultrasound, although not used in this case, can provide a more definitive answer. The superficial location of the synovial folds at the periphery of the radiohumeral compartment allows for an easy evaluation via ultrasound. Normal findings show a hyperechoic triangular shape surrounded by a thin, hypoechoic ring. Pathological findings are thickened synovial folds with irregular echogenicity and margins.5

MRI can provide a better overall assessment of any structural abnormality of the elbow and identifies most cases of ESFS, ruling out other possible aetiologies of elbow pain. Its diagnostic strength is weakened, however, when there is only a small quantity of fluid, or absence of focal synovitis.

CT arthrography or MRA is a highly sensitive study approaching 100% sensitivity in diagnosing ESFS (figure 6).1 This is due to intra-articular contrast administration highlighting joint surfaces and distending the capsule, which provides great visualisation of plicae. However, these tests are costly and may have more false positives.

Figure 6.

Magnetic resonance arthrography showing a thickened posterolateral plica and focal irregular synovitis (arrow). Adapted from Cerezal et al.2 Used with permission.

High-definition ultrasound and arthroscopic examination of the joint are the most valuable tools, as they allow not only direct inspection of the hypertrophic plica but also help identify the dynamic impact of the hypertrophic folds in motion.3

Measuring the thickness of a plicae can indicate whether it is likely to be symptomatic. Asymptomatic plicae are usually thinner than 3 mm.6

ESFS can be misdiagnosed as lateral epicondylitis, osteochondrosis dissecans, loose bodies, arthritis, compression of the posterior interosseous nerve or snapping of the triceps tendon.7

First-line treatment is rest from all strenuous activities, combined with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and physiotherapy.8 If conservative therapy for 3 months or more fails, arthroscopic excision of the pathologic plica is usually done.9

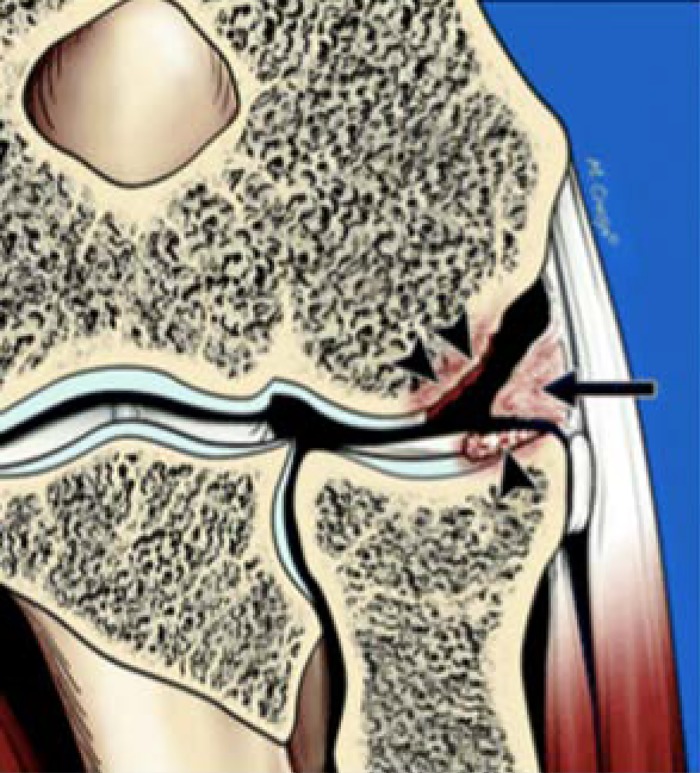

Early diagnosis and treatment are essential. Surgical intervention should not be delayed for lengthened conservative management, as erosion of the articular cartilage (figure 7) that could be prevented by early resection, will occur.2 10 However, surgery can lead to complications; conservative management is usually recommended for at least 8 weeks. Outcomes after arthroscopic resection and repair of chondral defects are excellent. In rare cases, open surgery is necessary, usually when large hypertrophic synovial plicae are present.3

Figure 7.

Typical features of elbow synovial fold syndrome, including thickened and inflamed plica (arrow) and chondral fraying of radial head and capitellum (arrowheads). Adapted from Cerezal et al.2 Used with permission.

ESFS can be found in athletes, especially those in sports that require repetitive motion of the elbow. It can be easily misdiagnosed. As in our case, even an MRI may show negative findings in the beginning. CT or MRA and dynamic ultrasound are helpful in diagnosing ESFS. Once diagnosed, 8–12 weeks of conservative management is a good first-line treatment. If conservative therapy fails, then arthroscopic excision is appropriate to avoid long term, irreversible erosion of the joint.

Learning points.

A snapping sensation with elbow flexion, as well as motion-dependent pain in the elbow, should make one consider the diagnosis of elbow synovial fold syndrome (ESFS).

Repetitive motions of the elbow, particularly in sports, such as weightlifting, golf, cheerleading, baseball and tennis, can lead to ESFS.

High-resolution ultrasound, CT arthrography or magnetic resonance arthrogram (not necessarily a regular MRI) can help lead to the definitive diagnosis of ESFS, given a congruent history and physical examination.

ESFS is first treated conservatively for at least 8 weeks, with rest, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and physiotherapy.

Arthroscopic excision of pathologic plicae may be needed if conservative therapy attempted for 3 months or more has failed.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors contributed to the conception and design, collection of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the article, generation of figures, collection of images, critical revision of the article for important intellectual content and final approval of the article.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Sanghi A, Jq L, Bush RJ, et al. Elbow synovial fold syndrome. Mil Med 2007;172:xii–xiii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cerezal L, Rodriguez-Sammartino M, Canga A, et al. Elbow synovial fold syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013;201:W88–W96. 10.2214/AJR.12.8768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinert AF, Goebel S, Rucker A, et al. Snapping elbow caused by hypertrophic synovial plica in the radiohumeral joint: a report of three cases and review of literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010;130:347–51. 10.1007/s00402-008-0798-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyers AB, Kim HK, Emery KH. Elbow plica syndrome: presenting with elbow locking in a pediatric patient. Pediatr Radiol 2012;42:1263–6. 10.1007/s00247-012-2407-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Celikyay F, Inanir A, Bilgic E, et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the posterolateral radiohumeral plica in asymptomatic subjects and in patients with osteoarthritis. Med Ultrason 2015;17:155–9. 10.11152/mu.2013.2066.172.usev [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Husarik DB, Saupe N, Pfirrmann CW, et al. Ligaments and plicae of the elbow: normal MR imaging variability in 60 asymptomatic subjects. Radiology 2010;257:185–94. 10.1148/radiol.10092163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jayanthi N. Epicondylitis (tennis and golf elbow). 2017. UpToDate https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epicondylitis-tennis-and-golf-elbow (accessed 1 Sep 2016).

- 8.LaPrade RF. Medial Synovial Plica Irritation Medication. 2017. Medscape http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/89985-medication (accessed 1 Sep 2017).

- 9.García-Valtuille R, Abascal F, Cerezal L, et al. Anatomy and MR imaging appearances of synovial plicae of the knee. Radiographics 2002;22:775–84. 10.1148/radiographics.22.4.g02jl03775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajeev A, Pooley J. Arthroscopic resection of humeroradial synovial plica for persistent lateral elbow pain. J Orthop Surg 2015;23:11–14. 10.1177/230949901502300103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]