Abstract

A 25-year-old man admitted for generalised muscle pain with an insidious onset 3 years ago. He had exercise intolerance and decrease in muscle strength, requiring gait support. He was previously healthy, with no chronic medication or recent history of drugs or toxics. National vaccination plan actualised with hepatitis B and tetanus vaccines administered 10 and 2 years, respectively, before symptom onset. No analytical, imaging or electromyography changes were found. Muscle biopsy revealed an inflammatory infiltrate predominantly macrophagic with aluminium deposits suggestive of macrophagic myofasciitis (MMF). It is probably associated with vaccines previously administered. MMF lesion can be regarded as pathological only if detected at least 18 months after last aluminic immunisation, as our case illustrates.

Keywords: muscle disease, pathology, medical management

Background

Macrophagic myofasciitis (MMF) is known since 1993 and was described for the first time in 1998 in France.1 Although muscle pain is frequent, some causes are rare diseases like MMF. It is an uncommon aluminium-induced myopathic syndrome characterised by specific muscle lesions assessing long-term persistence of aluminium hydroxide within macrophages at the site of previous immunisation. MMF was categorised under an ‘autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants’. Studies demonstrated that the muscle lesion is due to persistence for years, at the site of injection, of an aluminium hydroxide adjuvant used in vaccines against hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus and tetanus toxoid.2

Case presentation

A 25-year-old man, Caucasian, single, cook, was admitted to our hospital with generalised myalgias, an insidious onset having gradually aggravated in the last 3 years. It was associated with fatigue, exercise intolerance and decrease in muscle strength requiring a walking stick particularly after exercise. A symmetrical upper and lower limb loss of sensitivity to pain was observed sparing hands and feet. There was no chronic or new medication or toxic intake.

The patient had a personal history of migraine but no other known diseases. The national vaccination plan was actualised with hepatitis B and tetanus vaccines administered 10 and 2 years before the symptoms onset, respectively. There is no history of tobacco or alcohol intake.

It was known a Behçet’s disease diagnosis in a patient’s cousin. There are no other relevant familiar antecedents.

On physical examination, an inability to walk on heels was identified, difficulty to walk on toes and loss of strength after exercise with no distal/proximal or extensors/flexors dominance. There was associated loss of sensitivity to pain between the lower third of the arms to shoulder and lower third of legs to thigh.

Investigations

A complete neurological evaluation 2 months before by history, physical examination, analytical study, cranioencephalic CT and lumbar puncture found no alterations.

A complete evaluation with laboratory tests, including creatine kinase and aldolase, cervicodorsolumbar spine X-ray, cranioencephalic CT and MRI, electromyography and muscle MRI, was normal.

A muscle biopsy was performed for unexplained symptoms, associated disability and their long duration.

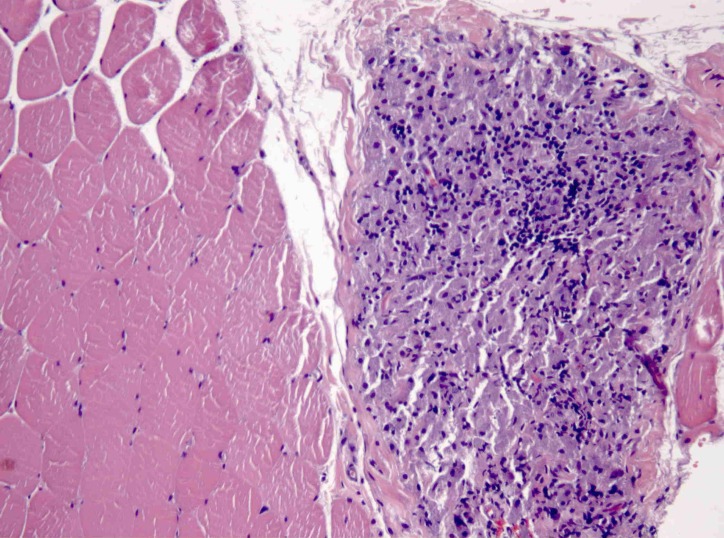

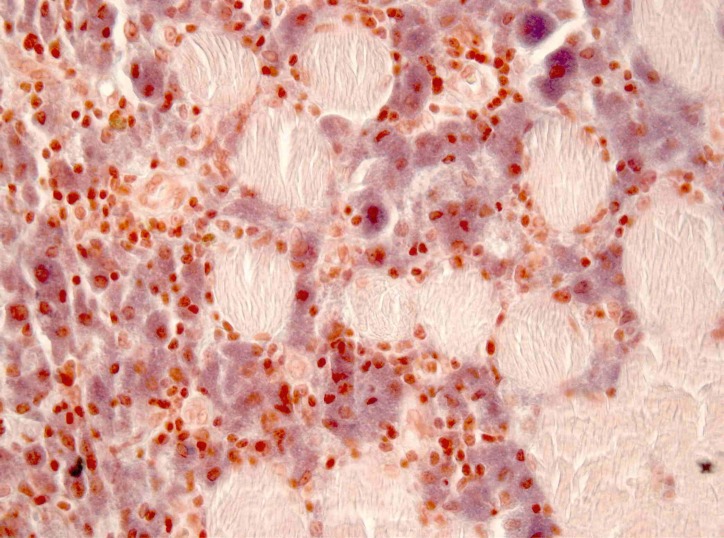

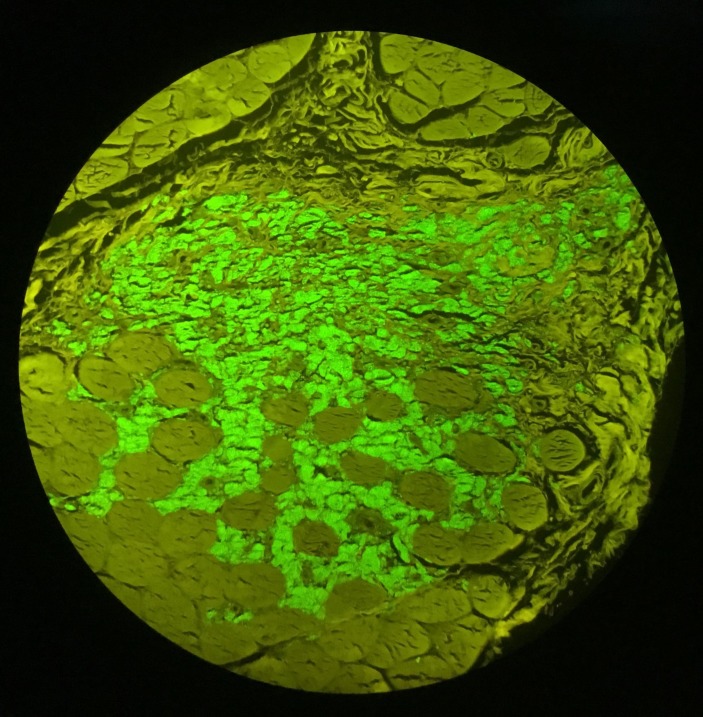

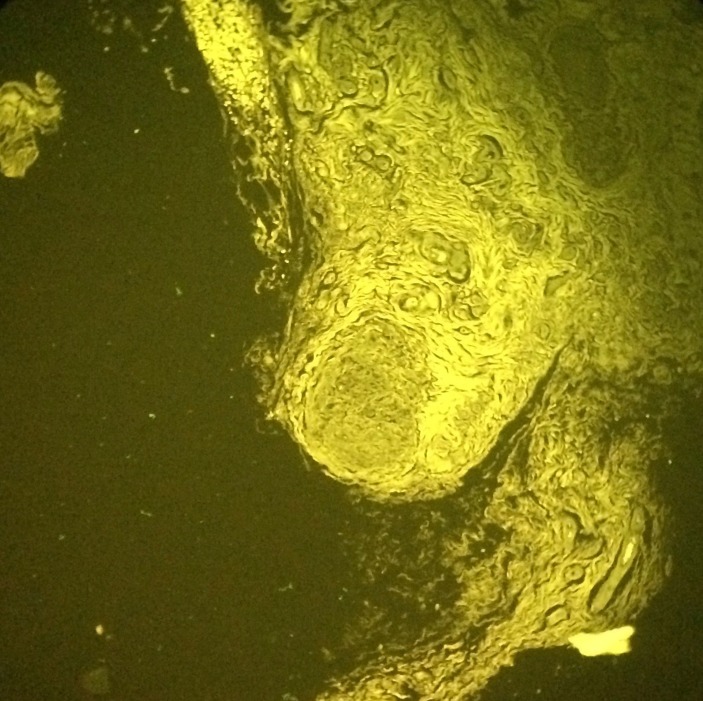

In perimysium and endomysium macrophagic cells with a basophilic, finely granular and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) positive content in cytoplasm were observed. There was also a smaller lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate. With aluminium–beryllium (Solocromo-Azurina), a specific immunohistochemistry technique, a bluish material in macrophagic cells was observed, which was compatible with aluminium. These lesions are suggestive of MMF (figures 1 and 2). Results were confirmed by Morin stain, a strong green granular fluorescence cytoplasm was observed (figure 3). We also show a negative case, a muscle biopsy with granulomatous myositis in a patient with sarcoidosis that was negative for Morin stain (figure 4).

Figure 1.

Deltoid muscle biopsy x200, H&E, macrophagic and lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate.

Figure 2.

Deltoid muscle biopsy x400, aluminium–beryllium staining, aluminium-containing macrophages (in blue).

Figure 3.

Muscle biopsy x200, Morin stain, macrophages showing a strong green, granular fluorescence cytoplasm.

Figure 4.

Muscle biopsy x100, Morin stain, granulomatous myositis in a patient with sarcoidosis showing negative macrophages.

Differential diagnosis

Due to its high incidence, first, we should exclude toxic or medication intake. Looking for a secondary cause, we have to search for hydroelectrolytic disorders (like potassium or magnesium disturbances) or other acute diseases, as an infection, for example. A long-lasting and progressive muscle pain and weakness requires the exclusion of a neurological central or peripheral disease, such a degenerative injury. Particularly in young patients, research for myopathic disorders or metabolic diseases should be performed. The study will be oriented by the results and clinical evolution.

Treatment

There is not specific treatment for this condition and patient care is difficult. Our patient started physiotherapy.

Outcome and follow-up

At 1-year follow-up, the symptoms are stable and the patient maintains his daily life activities.

Discussion

MMF is an immune-mediated condition characterised by systemic symptoms and specific histopathological lesions. This disease was categorised under an ‘autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants’ and is more common in female adults.2 3

Myalgias, arthralgias, asthenia, muscle weakness, chronic fatigue and fever may be present.4 The development of symptoms is usually slow, over several months, and diffuse myalgias are the most common with a prevalence ranging from 55% to 96%.5 In our case, myalgias were the major symptom.

Cognitive dysfunction was associated and can be the prominent clinical feature.6 In our case, there was not any clinical suggestion of cognitive disorder. Patients with cognitive deficit have impairment of executive functions and selective attention and patients without measurable cognitive deficits display significant weakness in attention. Episodic memory impairment affects verbal, but not visual or memory.7 MMF-associated cognitive impairment can be very severe and with time may often represent the first cause of disability.

Abnormal laboratory findings include elevated creatine kinase levels in 50% of patients, an aldolase elevated in 12.5% and a myopathic electromyogram that may be present in 25%.3

Only muscle biopsy confirms the diagnosis and typically shows infiltration of the subcutaneous tissue, epimysium, perimysium and perifascicular endomysium by sheets of large macrophages, with a finely granular PAS-positive content. Occasionally, a lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate can be seen.1 There is no significant muscle injury and macrophages with intracytoplasmic aluminium stained by the technique of aluminium–beryllium (Solocromo-Azurina) are observed.3 Morin stain detects aluminium with high sensitivity and specificity in human muscle and soft-tissue and may improve de diagnosis.8

Several positron emission tomography/CT with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (PET/CT) studies have investigated cognitive disorders. A peculiar spatial pattern of cerebral glucose hypometabolism in patients with long-lasting aluminium hydroxide-induced MMF was identified. Although muscle biopsy still is the gold standard for positive MMF diagnosis, FDG-PET should be performed in patients with suspected MMF and cognitive impairment.9 10

Patients with MMF commonly show subtle signs of chronic immune stimulation. Aluminium adjuvants are used to activate the immune system and thus to improve the protective response to vaccines. The persistence of aluminium hydroxide at the site of previous intramuscular injection was proven and there is an aberrant immune response with systemic symptoms.4 Adjuvants increase innate and adaptive immune responses and the local reaction to antigens. A chronic stimulation is possible the cause and a subsequently release of chemokines and cytokines, such as interleukin (IL) 1 and IL-18. In other hand, some animal studies have demonstrated widespread systemic distribution of aluminium-containing macrophages. Some macrophages accumulate locally, while other migrate to regional lymph nodes and through immune system reach other organs (brain, spleen and lymph nodes) causing symptoms.3

The discrepancy between the wide applications of aluminium-containing vaccines and the very limited number of MMF cases reported suggest that additional factors may influence the occurrence of disease. Some studies have implicated the Human Leukocyte Antigen–antigen D Related B1 (HLA-DRB1) typing as a predictor of an increased risk and the HLA-DRB1*01 phenotype has been associated with the development of MMF.4 Other factors, including drugs, environmental and toxic factors and the degree of local macrophage infiltration in the muscle may also influence the clinical manifestations.3

Our patient received vaccines with aluminium adjuvant 10 and 2 years before the symptoms—hepatitis B and tetanus vaccines, respectively. It has been described that time elapsed from last immunisation with an aluminium-containing vaccine for the onset of symptoms range from several months to years.4 5 MMF lesion can be regarded as pathological only if detected at least 18 months after last aluminic immunisation. It is not only about discovering MMF lesions but an MMF lesion of abnormally prolonged persistence. Although it is not possible to prove a causal link, findings support the diagnosis. Instead, there are minor cases of MMF without previous aluminium-containing vaccine administration, suggesting that other causes unrelated to vaccination need to be investigated in the pathogenesis of the disease.3

Learning points.

Valorize clinical history and non-specific symptoms.

Invasive tests may be needed, and its realisation should be discussed.

In a patient with myalgias, exercise intolerance and muscle weakness, clinical history must be carefully taken looking for the administration of aluminium-containing vaccines, and a muscle biopsy to search for macrophagic myofasciitis should be considered.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors have a role in the management of the patient in the hospital admission. DSS and AS received the patient and oriented all the management of them during hospital admission and after discharge. RMS supervised the work of the medical team. OR is the neuropathologist who found alterations in the muscle biopsy that allowed the diagnosis. DSS and AS wrote the manuscript. The manuscript was revised critically by RMS who provided the final approval of the version published.

Funding: We have not a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Gherardi RK, Authier FJ. Macrophagic myofasciitis: characterization and pathophysiology. Lupus 2012;21:184–9. 10.1177/0961203311429557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perricone C, Colafrancesco S, Mazor RD, et al. Autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants (ASIA) 2013: Unveiling the pathogenic, clinical and diagnostic aspects. J Autoimmun 2013;47:1–16. 10.1016/j.jaut.2013.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santiago T, Rebelo O, Negrão L, et al. Macrophagic myofasciitis and vaccination: Consequence or coincidence? Rheumatol Int 2015;35:189–92. 10.1007/s00296-014-3065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Israeli E, Agmon-Levin N, Blank M, et al. Macrophagic myofaciitis a vaccine (alum) autoimmune-related disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2011;41:163–8. 10.1007/s12016-010-8212-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rigolet M, Aouizerate J, Couette M, et al. Clinical features in patients with long-lasting macrophagic myofasciitis. Front Neurol 2014;5:230 10.3389/fneur.2014.00230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Der Gucht A, Aoun-Sebaiti M, Kauv P, et al. FDG-PET/CT brain findings in a patient with macrophagic myofasciitis. Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2016;50:80–4. 10.1007/s13139-015-0371-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aoun Sebaiti M, Kauv P, Charles-Nelson A, et al. Cognitive dysfunction associated with aluminum hydroxide-induced macrophagic myofasciitis: A reappraisal of neuropsychological profile. J Inorg Biochem 2018;181 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2017.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chkheidze R, Burns DK, White CL, et al. Morin stain detects aluminum-containing macrophages in macrophagic myofasciitis and vaccination granuloma with high sensitivity and specificity. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2017;76:323–31. 10.1093/jnen/nlx011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Der Gucht A, Abulizi M, Blanc-Durand P, et al. Predictive value of brain 18F-FDG PET/CT in macrophagic myofasciitis?: a case report. Medicine 2017;96:39 10.1097/MD.0000000000008134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Der Gucht A, Aoun Sebaiti M, Guedj E, et al. Brain 18F-FDG PET metabolic abnormalities in patients with long-lasting macrophagic myofascitis. J Nucl Med 2017;58:492–8. 10.2967/jnumed.114.151878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]