Introduction

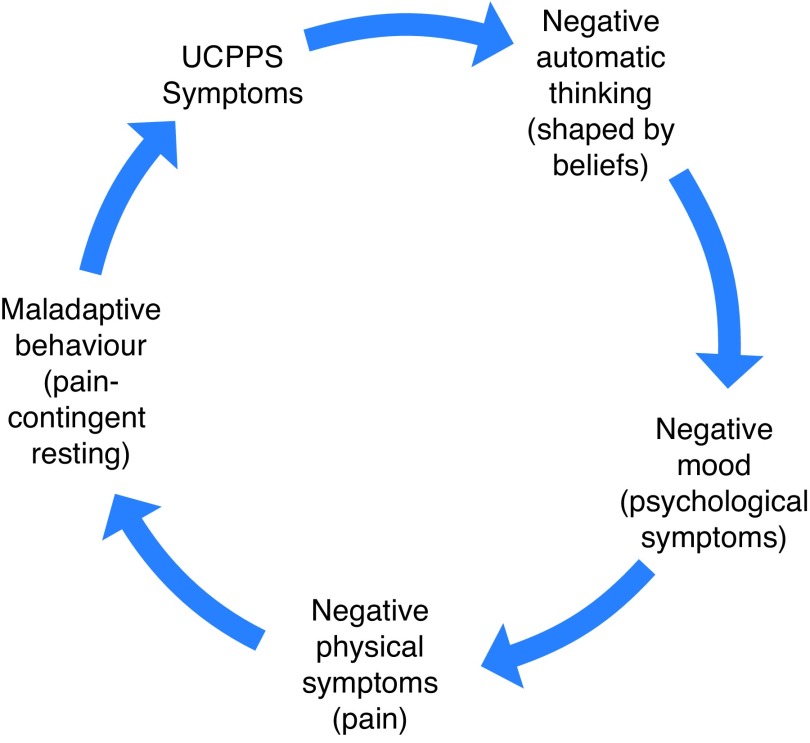

Urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes (UCPPS) pain severely impact patient quality of life. Regardless of the infamous “chicken and egg” question concerning UCPPS symptoms (i.e., pain) and psychological distress, when we see our patients in clinic, many are reporting stress or depression. Fortunately, several biopsychosocial risk factors have been described in UCPPS. By identifying these risk factors in your patients, you can more clearly understand the dynamics of patient reactions to physical, psychological, and social symptoms, which may be recursive and complicated in nature (Fig. 1), and feel more confident in managing and referring such patients for appropriate treatment. Risk factors like depression, social support, coping with pain, and pain catastrophizing have attracted both research and clinical attention. These domains are identified in Table 1. Below are practical management suggestions for urologists.

Fig. 1.

Cycle of symptom impact in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS).

Table 1.

Psychosocial risk factors and clinical recognition through patient report

| Psychosocial domain | Clinical recognition, patient reports |

|---|---|

| Stress/anxiety |

|

| Depression |

|

| Pain-contingent rest |

|

| Spousal/partner social support |

|

| Pain catastrophizing |

|

Practice tips

Tip 1: Stress/anxiety

To help manage stress/anxiety, it is suggested that the urologist inquire on and suggest the strengthening of the patient’s supportive relationships. Research is clear that social support buffers stress. Relaxation methods (across a wide variety of platforms, online, classes, etc.) are also known to combat stress and anxiety. A discussion on what patients have tried and encouragement to engage in this strategy is useful. Other urologists suggest that telling their patients to invest in their emotional health, make time with important people in their life, and to discontinue unimportant activities can help. Walking with others is a great recommendation.

Tip 2: Depression

The management of depression is important. Medical therapy with a drug that has dual purpose for pain and mood (e.g., tricyclic antidepressant) may be indicated. Without suggesting the urologist become a uro-psychologist, listening is an important relationship builder. Once facts are gathered, referral to appropriate therapy resource (psychologist, social work, psychiatry) is suggested. Some patients may have access to a local support group, where readings and activities on self-management of depressive symptoms may be addressed (e.g., Mind over Mood). There are also several online resources that have evidence of efficacy (e.g., Mood Gym; https://moodgym.com.au/). Ask questions about self-harm and suicide; do not avoid these because you are afraid of the answer. If suicidal ideation is real, then urgent referral to the appropriate local treatment centre is mandatory.

Tip 3: Pain-contingent resting

To help manage pain-contingent resting (resting or doing very little activity as a mal-adaptive coping technique), endorse the idea of activity as essential to a healthy lifestyle, from both a physical de-conditioning and mental health perspective. Discuss benefits of activity on UCPPS symptoms.

Tip 4: Spousal/partner interactions

To help manage spousal/partner interactions, research suggest that distraction from pain and symptoms is a helpful support. Couples should avoid solicitous responses, in particular for men (wherein partner does much of the family, household workload of the patient). It is important for patients to continue to participate at their maximum level. Urologists can also suggest that activity staves off stress and depression.

Tip 5: Pain catastrophizing

Pain catastrophizing (rumination about and magnification of symptoms, as well as helplessness) may be one of the most important psychosocial factors in need of attention. Once recognized, urologists can ask if patients have someone they trust with whom they can share these feelings. Urologists can also examine patients’ personal and social supports. These helpless and anxious thoughts are usually the worst-case scenario in the patient’s mind, so asking questions about the rational likelihood of the feared event happening is an important start. Also asking “What if···” questions about that feared scenario actually happening to them is paradoxically useful. Follow up by asking them how they would “cope or manage” if the event did happen makes the patients consider options they would have never entertained in their anxious state. This self-awareness is important. For more challenging patients, cognitive behavioural therapies for pain, support groups, or even readings for pain self-management may be useful.

Summary

It is imperative that UCPPS be recognized as a chronic pain condition that requires strategies outside of a purely biomedical model. UCPPS is not a physical phenomenon, but must be conceptualized as a complex physical, emotional, and interpersonal disease state that carries with it important negative psychosocial outcomes. The good news is that urologists can have significant impact on their patients’ quality of life through these simple and effective management suggestions. Our group in Kingston has developed and is presently testing a novel cognitive behavioural program designed to benefit patients suffering from urologic chronic pain.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The author reports no competing personal or financial conflicts related to this work

This paper has been peer reviewed.

Recommended reading

- 1.Tripp DA, Nickel JC. The psychology of urologic chronic pelvic pain: A primer for urologists who want to know how to better manage chronic prostatitis and interstitial cystitis. American Urological Association Update Series. 2011;30:30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tripp DA, Nickel JC, Katz L. A feasibility trial of a cognitive-behavioural symptom management program for chronic pelvic pain for men with refractory chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Can Urol Assoc J. 2011;5:328–32. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tripp DA, Nickel JC, Krsmanovic A, et al. Depression and catastrophizing predict suicidal ideation in tertiary care patients with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) Can Urol Assoc J. 2016;10:383–8. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]