Abstract

Purpose

To assess how social fraternity involvement (i.e., membership and residence) in college relates to substance use behaviors and substance use disorder symptoms during young adulthood and early midlife in a national sample.

Methods

National multi-cohort probability samples of U.S. high school seniors from the Monitoring the Future study were assessed at baseline (age 18) and followed longitudinally via self-administered surveys across seven follow-up waves to age 35. The longitudinal sample consisted of 7019 males and 8661 females, of which 10% of males and 10% of females were active members of fraternities or sororities during college.

Results

Male fraternity members who lived in fraternity houses during college had the highest levels of binge drinking and marijuana use relative to non-members and non-students in young adulthood that continued through age 35, controlling for adolescent sociodemographic and other characteristics. At age 35, 45% of the residential fraternity members reported alcohol use disorder (AUD) symptoms reflecting mild to severe AUDs; their adjusted odds of experiencing AUD symptoms at age 35 were higher than all other college and non-college groups except non-residential fraternity members. Residential sorority members had higher odds of AUD symptoms at age 35 when compared to their non-college female peers.

Conclusion

National longitudinal data confirm binge drinking and marijuana use are most prevalent among male fraternity residents relative to non-members and non-students. The increased risk for substance-related consequences associated with fraternity involvement was not developmentally limited to college and is associated with higher levels of long-term AUD symptoms during early midlife.

Introduction

Previous research has shown that college students who belong to social fraternities or sororities have considerably higher rates of substance use than their college peers who do not join such organizations as a result of both selection and socialization effects [1–6]. Selection and socialization effects often work in conjunction: for example, individuals who are heavy drinkers before starting college may select specific fraternities and sororities with a reputation for heavy drinking while being a member of such fraternities or sororities serves to increase their heavy drinking [4–7]. The college subculture that promotes substance use appears to be strongest among college males who belong to and reside in social fraternities [1–4,7,8]. For instance, nearly nine in every ten social fraternity male members who reside in fraternity houses reported binge drinking in the past two-weeks [8], relative to 32.4% of college young adults and 28.7% of non-college young adults [9]. Longitudinal research has shown that greater cumulative exposure to the social Greek system leads to increased heavy drinking during the college years, particularly among college males who belonged to and resided in fraternities [1,4].

A key developmental question is the extent to which this increased risk for substance-related consequences among those involved in the social Greek system continues beyond the college years. Binge drinking tends to decline after college [9–11], with some evidence that this is true as well for those who had been involved in social fraternities and sororities [1,6]. However, questions remain regarding the ongoing relative risk associated with social Greek membership compared to the general population as these individuals transition into adulthood. To date, relevant longitudinal studies have not extended beyond age 30 and have not examined whether the heightened rates of substance use among social Greek members are associated with higher rates of substance use disorder (SUD) symptoms in adulthood. The present study is designed to address this gap using national longitudinal data extending through young adulthood and age 35.

Substance use during and after college

The prevalence trends of some substance use behaviors such as binge drinking and nonmedical prescription stimulant use is higher among college young adults relative to their non-college peers [9,11–14]. In contrast, trends in past-year marijuana are somewhat similar between college and non-college youth while monthly cigarette smoking is more prevalent among non-college youth [9,14]. Notably, binge drinking and nonmedical prescription stimulant use tend to be more prevalent among college males relative to females [9,13,14]. Several studies have shown that binge drinking and other substance use behaviors often decline as young adults graduate from college and assume post-college responsibilities while their non-college peers do not experience the same levels of declines during the same time period [9,11,12].

Fraternity and sorority substance use after college

At least two previous longitudinal studies from the same university have demonstrated that fraternity or sorority involvement was associated with heavy drinking levels during college but these differences were no longer present 3 years after college [1,6]. Prior research has concluded that additional longitudinal research is needed to examine if these findings extend to other substances, substance-related consequences, national samples, and further into adulthood [1,4,6].

Based on sex differences in substance use behaviors, another important question is whether substance use levels following college track differently for males involved in fraternities than females involved in sororities [1,3,4,6,7]. There is some evidence that socialization effects for substance use during college are more powerful for men than for women [2,5,7]. For instance, undergraduate men tend to increase their substance use more than women over the course of their college careers, and evidence suggests strong socialization effects of fraternity membership on substance use during college [2,5,7].

Prior studies examining the effects of collegiate fraternity and sorority involvement on substance use are limited by multiple factors. Most have been cross-sectional and examined a limited range of substance use behaviors; the extant longitudinal studies tend to begin with college and end by age 30. Furthermore, several studies have focused on samples drawn from single institutions and cohorts; this limits the potential generalizability of the findings to college students nationally because past research has found wide variation between individual colleges in prevalence of substance use [2,15]. Finally, most prior work has excluded individuals not attending college. The present study is designed to address these gaps.

Present study

There is clear evidence that social fraternity and sorority involvement is associated with heightened substance use and alcohol-related problems during college [1,4,6,8]. It is less clear, however, the extent to which substance use behaviors and SUDs continue beyond the college years, and particularly past young adulthood. That is, to what extent is this experience a developmental disturbance with limited lingering effects versus a sensitive period experience that sets the stage for long-term difficulties [17–19]? The present study, which draws on U.S. national panel data from the Monitoring the Future (MTF) project, includes multiple cohorts of high school seniors followed through young adulthood to age 35 to provide needed evidence regarding potential long-term effects of social fraternity and sorority involvement on subsequent substance use behaviors and SUD symptoms. Based on the notable sex differences in substance use observed in past studies [1,4,6,9,14], we examined the effects of social fraternity or sorority involvement separately for males and females in our main analyses. We hypothesized that college students involved with fraternities or sororities, particularly those who are residential members, are at greater risk for ongoing substance use across young adulthood and adult SUD symptoms when compared to their college and non-college peers; furthermore, we hypothesize that among all groups, residential fraternity males are the greatest risk for ongoing substance use and adult SUD symptoms.

Methods

Study Design

This prospective study used national panel data from the Monitoring the Future (MTF) study [9,19,20]. Based on a three-stage sampling procedure, MTF surveys nationally representative samples of approximately 17,000 U.S. high school seniors each year using questionnaires administered in classrooms. Approximately 2,400 high school seniors are randomly selected for biennial follow-ups each year and surveyed biennially using mailed questionnaires through age 30 and at age 35.

The study period for respondents at age 35 was between 2005 and 2013 (12th grade cohorts 1988-1996). The survey items regarding active membership in fraternities and sororities were added in 1990. The response rates at baseline ranged from 83% to 86% during the study period; almost all of non-response was due to the given student being absent from school the day of survey administration (about 1% refuse to participate on the day of survey administration). The MTF panel oversamples drug users from the 12th grade sample to secure a population of drug users to follow into adulthood (appropriate panel weights are then used to best approximate population estimates in the follow-up). The overall response rate for the longitudinal sample from 12th grade to first follow-up between 1989 to 1997 is 71.1%; from 12th grade to age 35 follow-up between 2005 to 2013 is 43.4%. Given potential differential attrition bias, this study incorporates attrition weights to the panel weights that account for key factors in the MTF that have been shown to be associated with panel attrition [21–23]. The project design and sampling methods are described in greater detail elsewhere [9,19,20].

As illustrated in Table 1, the unweighted longitudinal sample included 15,680 individuals who completed the first follow-up at age 19/20 and 9,060 respondents who completed follow-ups to age 35. The sample was 49.0% female and 51.0% male. The racial/ethnic distribution was 63.5% White, 15.8% Black, 10.9% Hispanic, and 9.7% multiracial or from other racial/ethnic categories. Approximately 25.7% of the sample did not attend college, 64.1% attended a 2- or 4-year college (part- or full-time) and were not involved in a fraternity or sorority, 7.9% were active members in a fraternity or sorority (but did not reside in a fraternity or sorority house), and 2.3% were active members and resided in a fraternity or sorority house for at least one semester.

Table 1.

Baseline descriptive statistics and college status for the longitudinal sample

| Baseline sociodemographic characteristics and college status | Study Sample (Unweighted n = 15,680)1 | Male Study Sample (Unweighted n = 7,019)1 | Female Study Sample (Unweighted n = 8,661)1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |

| 12th Grade Cohort Year | |||

| 1988-1990 | 32.5 (5411) | 33.2 (2500) | 31.8 (2911) |

| 1991-1993 | 35.3 (5312) | 36.0 (2409) | 34.5 (2903) |

| 1994-1996 | 32.2 (4957) | 30.8 (2110) | 33.7 (2847) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 51.0 (7019) | – | – |

| Female | 49.0 (8661) | – | – |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 63.5 (12005) | 63.3 (5438) | 63.7 (6567) |

| Black | 15.8 (1304) | 14.9 (490) | 16.9 (814) |

| Hispanic | 10.9 (1148) | 11.2 (491) | 10.7 (657) |

| Other race | 9.7 (1223) | 10.7 (600) | 8.8 (623) |

| Parental Education | |||

| Neither parent has a college degree | 58.8 (8541) | 57.1 (3647) | 60.6 (4894) |

| At least one parent has a college degree or higher | 41.2 (7139) | 42.9 (3372) | 39.4 (3767) |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 18.5 (2999) | 17.9 (1298) | 19.1 (1701) |

| Midwest | 23.2 (4491) | 22.7 (2013) | 23.7 (2478) |

| South | 37.7 (5174) | 37.3 (2257) | 38.0 (2917) |

| West | 20.6 (3016) | 22.1 (1451) | 19.1 (1565) |

| Urbanicity | |||

| Large metropolitan statistical area | 25.8 (3906) | 25.2 (1719) | 26.4 (2187) |

| Other metropolitan statistical area | 49.0 (7660) | 49.5 (3456) | 48.6 (4195) |

| Non-metropolitan statistical area | 25.2 (4114) | 25.3 (1835) | 25.0 (2279) |

| College Attendance and Fraternity/Sorority Membership/Residence2 | |||

| Did not attend college | 25.7 (3512) | 28.3 (1718) | 22.9 (1794) |

| Attended college, not active frat./sor. member | 64.2 (10364) | 61.6 (4462) | 66.8 (5902) |

| Attended college, active frat./sor. member/resident | 7.9 (1343) | 7.3 (565) | 8.5 (778) |

| Attended college, active frat./sor. member/non-resident | 2.3 (428) | 2.8 (248) | 1.8 (180) |

Weighted estimates to account for attrition at age 35 were used to estimate percentages. Unweighted sample sizes are presented in parentheses.

College attendance was defined as attending a 2- or 4-year college (part- or full-time). Respondents who indicated attending college were asked whether they were involved in a fraternity or sorority (excluding honorary fraternities/sororities) and if they had lived in a fraternity or sorority. Accordingly, these variables were combined to make the mutually exclusive four-category item based on information provided on follow-ups 1 through 3 (follow-up 1 – age 19/20, follow-up 2 – age 21/22, follow-up 3 – age 23/24) to capture involvement in college and Greek life between the ages of 19 and 24.

Measures

The MTF study assesses a wide range of behaviors, attitudes, and values. Based on previous research, we selected specific measures for these analyses from the baseline surveys to include as controls [4,9,20–26], including baseline cohort year (i.e., 1988-1990, 1991-1993, 1994-1996), sex (i.e., male, female), race/ethnicity (i.e., White, Black, Hispanic, Other), parental education (i.e., at least one parent with a college degree, neither parent has a college degree), U.S. Census geographic location (i.e., Northeast, Midwest, South and West), urbanicity (i.e., metropolitan statistical area: large MSA, other MSA, and non-MSA), truancy (i.e., skipped school in past-month, did not skip school), high school grade point average (i.e., C+ or lower, B- or higher), and social evenings out with friends (i.e. 3 or more evenings out with friends during typical week, 2 or less evenings). Depending on outcome in the analyses, we also included as controls baseline cigarette use, binge drinking, marijuana use, other illicit drug use, and nonmedical prescription drug use.

Substance use behaviors at baseline (12th grade) and all follow-ups (ages 18 to 35) were consistently measured with the following reliable and valid measures [9,20,27,28].

Binge drinking was measured using the following item: “Think back over the last two weeks. How many times have you had five or more drinks in a row?” The response scale ranged from (1) none to (6) 10 or more times.

Cigarette smoking was measured using the following item: “How frequently have you smoked cigarettes during the past 30 days?” The response scale ranged from (1) none to (7) 2 or more packs per day.

Marijuana use was measured using the following item: “On how many occasions (if any) have you used marijuana during the last 12 months?” The response scale ranged from (1) no occasions to (7) 40 or more occasions.

Other illicit drug use–including LSD, psychedelics other than LSD, inhalants, cocaine, heroin–was measured with the following item for each illicit drug class: “On how many occasions (if any) have you used [DRUG] during the last 12 months?” The response scale for each drug was identical to marijuana use.

Nonmedical prescription drug use—narcotics/opioids, amphetamines/stimulants, tranquilizers/anxiolytics, and sedatives/sleeping medications–was measured with the following item for each prescription drug class: “On how many occasions (if any) have you used [DRUG] during the last 12 months?” The response scale for each drug was identical to marijuana use.

SUD symptoms at age 35 were measured with questions based on DSM criteria for alcohol use disorder (AUD), cannabis use disorder (CUD), and other drug use disorders (ODUD). Although these measures of SUD symptoms do not yield a clinical diagnosis, the items are consistent with SUD as measured in other large scale surveys [29–31] and have been used in the past to reflect DSM-IV and DSM-5 AUDs, CUDs and ODUDs [21–23,32,33]. Respondents were asked to report SUD symptoms during the past five years related to AUD, CUD and ODUD (which included illicit drugs such as cocaine, LSD, other hallucinogens, heroin, inhalants, and nonmedical use of prescription anxiolytics, opioids, sedatives, and stimulants). Fifteen items were used to develop the following eight of the eleven DSM-5 criteria that were consistent with AUD, CUD, and ODUD. The eight criteria were summed to obtain an overall number of criterion endorsed. We followed recommended practice that any use disorder (including mild, moderate, or severe) is indicated by meeting two or more of the criteria [24,25,34,35].

College student status was based on respondents reporting whether they are currently attending a 2- or 4-year college (part- or full-time enrollment during the month of March) during at least one of the first three follow-up waves (modal ages 19-24).

Fraternity/sorority membership was defined with a single item asking whether an individual was an active member of a fraternity or sorority (excluding honorary ones) during any of the first three follow-up waves (modal ages 19-24).

Fraternity/sorority residence was defined with a single item asking respondents whether they currently live (i.e., during the month of March) in a fraternity or sorority during any of the first three follow-up waves (modal ages 19-24).

Data Analysis

Logistic regression models using the generalized estimating equations (GEE) methodology with an autoregressive correlation structure was used to assess how membership in fraternities and sororities during ages 19-24 was associated with substance use across the 8 waves (ages 18-35) and SUD symptoms at age 35 [36,37]. Note that the sample used in the first set of GEE analyses (concerning substance use spanning ages 18-35) included respondents who completed at least two consecutive waves; the second set of GEE analyses (concerning substance use disorders at age 35) include only those respondents present for the age 35 survey (and independent correlation structure was used for this set of analyses – this was chosen due to variance being constant within subjects [there was no variation within subjects due to the cross-sectional nature of the variables used in this second set of analyses]).

Based on the estimated GEE logistic regression models stratified by sex, we computed adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) describing the relationships of fraternity and sorority membership with the odds of substance use (time-varying ages 18-35) and SUD symptoms (time invariant age 35 only). All models included age 18 control variables as follows: cohort year, race/ethnicity, parents’ education, geographic region, metropolitan statistical area, truancy, high school grades, social evenings out, cigarette smoking, binge drinking, marijuana use, other illicit drug use, and nonmedical prescription drug use. As noted in Table 2, models estimating given substance use behaviors (e.g., binge drinking in Models 2 and 7) remove the specific substance use behavior at age 18 (e.g., binge drinking at age 18 in Models 2 and 7) as a control variable because it is already included as part of the outcome. In models that combined males and females, sex was also included as a control. All GEE analyses used attrition weights to account for potential bias due to differential attrition at age 35 [21–23]. All the statistical analyses were performed using commercially available software (STATA/SE v.14.2; STATA Corp., College Station, TX).

Table 2.

GEE logistic regression assessing the association between involvement in fraternities/sororities (ages 19-24) and substance use from ages 18 through 35.

| Males College attendance and fraternity/sorority involvement (ages 19-24) |

Model 1 Cigarette use (past 30 days) 1 AOR (95% CI) |

Model 2 Binge drinking (past two weeks) 1 AOR (95% CI) |

Model 3 Marijuana use (annual) 1 AOR (95% CI) |

Model 4 Other illicit drug use (annual) 1 AOR (95% CI) |

Model 5 Nonmedical Rx drug use (annual) 1 AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Active frat. member/resident | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Active frat. member/non-resident | 1.08 (.746, 1.56) | .592 (.450, .777)*** | .820 (.597, 1.12) | 0.983 (.624, 1.54) | 1.47 (.977, 2.22) |

| Attended college not in frat | 1.06 (.777, 1.44) | .344 (.273, .435)*** | .567 (.438, .734)*** | 0.739 (.504, 1.08) | 1.06 (.762, 1.48) |

| Never attended college | 1.80 (1.27, 2.54)*** | .339 (.260, .441)*** | .498 (.368, .673)*** | 0.634 (.418, .962)* | 1.18 (.828, 1.70) |

| Age (linear) | 1.09 (1.04, 1.14)*** | 1.36 (1.29, 1.43)*** | 1.09 (1.03, 1.15)** | 1.11 (1.02,1.21)** | 0.783 (.727, .845)*** |

| Age (quadratic) | .973 (.966, .980)*** | .953 (.946, .960)*** | .965 (.958, .973)*** | 0.965 (.953,.976)*** | 1.03 (1.02, 1.04)*** |

|

| |||||

| 2 n = 4,121 | 2 n = 4,000 | 2 n = 4,166 | 2 n = 4,303 | 2 n = 4,286 | |

| Females College attendance and fraternity/sorority involvement (ages 19-24) |

Model 6 Cigarette use(past 30 days) 1 A OR (95% CI) |

Model 7 Binge drinking(past two weeks) 1 A OR (95% CI) |

Model 8 Marijuana use (annual) 1 A OR (95% CI) |

Model 9 Other illicit drug use (annual) 1 A OR (95% CI) |

Model 10 Nonmedical Rx drug use (annual) 1 A OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Active sor. member/resident | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Active sor. member/non-resident | 1.48 (1.01, 2.15)* | .734 (.574, .938)* | .744 (.521, 1.06) | 1.20 (.531, 2.74) | 1.15 (.786, 1.68) |

| Attended college not in sor. | 1.75 (1.24, 2.47)*** | .478 (.383, .596)*** | .769 (.553, 1.07) | 1.91 (.876, 4.16) | 1.27 (.909, 1.79) |

| Never attended college | 2.73 (1.89, 3.95)*** | .445 (.348, .570)*** | .591 (.415, .841)** | 1.50 (.672, 3.35) | 1.17 (.813, 1.70) |

| Age (linear) | 1.00 (.965, 1.05) | 1.15 (1.10, 1.20)*** | 1.01 (.969, 1.06) | .988 (.904, 1.08) | .700 (.659, .744)*** |

| Age (quadratic) | .980 (.974, .986)*** | .962 (.955, .968)*** | .968 (.961, .976)*** | .970 (.956, .984)*** | 1.040 (1.03, 1.05)*** |

|

| |||||

| 2 n = 5,504 | 2 n = 5,310 | 2 n = 5,569 | 2 n = 5,713 | 2 n = 5,695 | |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

AOR = adjusted odds ratio.

Each model (1-10) included age 18 controls for the following: cohort year at baseline,, race/ethnicity (i.e., White, Black, Hispanic, Other), parental education (i.e., at least one parent with a college degree vs. neither parent has a college degree), U.S. Census geographic region (i.e., Northeast, Midwest, South and West), metropolitan statistical area (i.e., large MSA, other MSA, and non-MSA), truancy (i.e., skipped school in past-month versus not), high school grades (i.e., C+ or lower versus B- or higher), and frequency of evenings out with friends (i.e., 3 times or more during a typical week versus 2 times or less). Also included as controls are age 18 past 30-day cigarette use, past two-week binge drinking, past-year marijuana use, past-year illicit drug use other than marijuana, and past-year nonmedical use of prescription drugs; however, note that the specific substance being assessed (e.g., binge drinking in Models 2 and 7) is not be included as an age 18 control variable (e.g., binge drinking at age 18 is not included as control in Models 2 and 7) because it is part of the GEE outcome.

Sample sizes vary due to missing data on the items used in the analyses. All models use weights to account for attrition at age 35.

Results

Table 2 shows the results of the GEE logistic regression analyses examining the association between fraternity and sorority status (between ages 19-24) on the time-varying outcomes for substance use (across ages 18-35). All age 18 sociodemographic and behavioral controls described earlier are included in each model (see Table 2). According to models 1 through 5 for males, respondents who lived for at least one semester in a fraternity house had greater odds of past two-week binge drinking across ages 18-35 compared to peers who were active members (did not live in a fraternity house), who attended college (not involved in fraternities), and who did not attend college. Males who lived for at least one semester in a fraternity house also had greater odds of past-year marijuana use when compared to peers who attended college (not involved in fraternities) and who did not attend college. Additionally, males who lived for at least one semester in a fraternity house had greater odds of past-year other illicit drug use, but had lower odds of past-30 day cigarette smoking when compared to males who did not attend college. These residential fraternity members did not differ from the other two college-based groups on cigarette, other illicit drug, and nonmedical prescription drug use; residential fraternity members also did not differ with non-residential active fraternity members with respect to marijuana use.

Models 6 through 10 in table 2 show that female respondents who lived for at least one semester in a sorority house had greater odds of past two-week binge drinking and lower odds of past-30 day cigarette use across ages 18-35 compared to their female peers who were active members (did not live in a sorority house), who attended college (not involved in sororities), and who did not attend college. Female respondents who lived for at least one semester in a sorority house also had greater odds of past-year marijuana use when compared to females who did not attend college; however, no differences in past-year marijuana use were found with respect with the other two college-based groups. Finally, no differences were found between residential sorority members and the other three groups with respect to past-year other illicit drug use and past-year nonmedical prescription drug use.

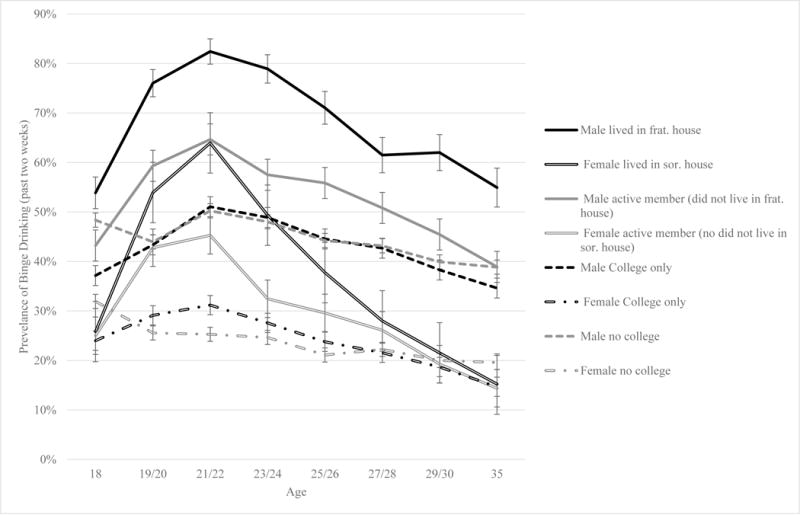

It should also be noted that additional analyses (see supplemental Table A) found that males who lived in a fraternity house had greater odds of binge drinking across ages 18-35 when compared to females who lived in sorority houses, male and female active members (did not live in a fraternity or sorority house), male and females who attended college (not involved in Greek life), and males and females who never attended college. These results were similar for past-year marijuana use, with the exception that the odds of marijuana use being similar between males who lived in fraternity houses and male fraternity members who did not live in a fraternity house. Figure 1 shows the observed differences with respect to binge drinking across ages 18-35 for these 8 groups, and illustrates the elevated rates of binge drinking over time among males who lived in fraternity houses.

Figure 1.

Observed differences in binge drinking based on fraternity/sorority involvement, college attendance, and sex across the seventeen-year study period

1Percentages were calculated using weights to account for attrition at age 35. 95% confidence intervals are based on standard errors obtained using Taylor linearization.

2The available sample sizes (unweighted) were the following at each age: 18 (n = 15,046), 19/20 (n = 15,117), 21/22 (n = 12,255), 23/24 (n = 11,330), 25/26 n = 10,563), 27/28 (n = 10,077), 29/30 (n = 9605), 35 (n = 8528).

With respect to the overall pattern of substance use between the ages of 18 and 35, the models in Table 2 show either significant linear (positive) or quadratic (negative) associations between age and several substance use behaviors, indicating that the odds of cigarette use, binge drinking, marijuana use, and other illicit drug use significantly increase after age 18 and then significantly decline as respondents transition into adulthood (see Figure 1 as an example). The odds of nonmedical prescription drug use decrease after age 18, but begin to increase during the transition into adulthood.

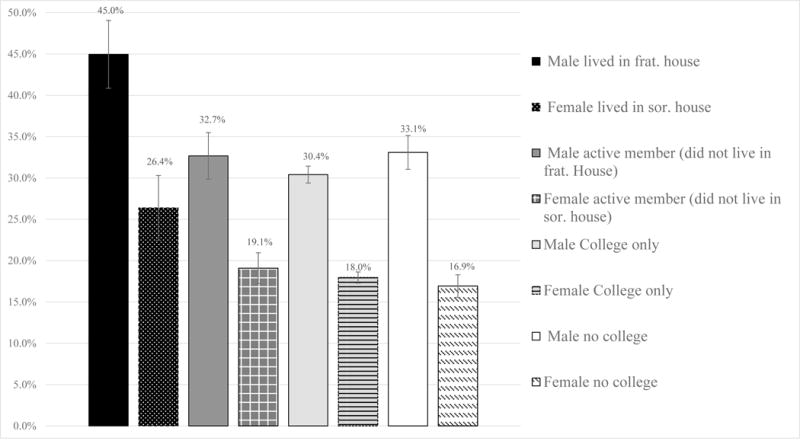

Table 3 shows the findings from the GEE logistic regression models examining the association between fraternity and sorority status and SUD symptoms at age 35. All models include the age 18 sociodemographic and behavioral controls described earlier (see Table 3). The results for males in models 1 through 3, concerning AUD, CUD, and ODUD symptoms, respectively, indicate that respondents who lived for at least one semester in a fraternity house had higher odds of reporting symptoms of AUD at age 35 when compared to their peers who were not active in fraternities (i.e., attended college and not involved in fraternities and did not attend college); no significant differences were found for age 35 CUD and ODUD symptoms. Models 4 through 6 for females indicate that respondents who lived in a sorority for at least one semester had higher odds of reporting symptoms of AUD and lower odds of ODUD symptoms at age 35 when compared to their peers who did not attend college (no differences were found with respect to the other two college based groups); no significant difference were found for age 35 CUD symptoms. Additional analyses (see supplemental Table B) also found that males who lived in a fraternity house for at least one semester had significantly higher odds of reporting AUD symptoms at age 35 when compared to all other groups except non-resident fraternity males. Figure 2 shows percentages of two or more AUD symptoms at age 35 across these 8 groups, illustrating the elevated rates of AUD symptoms at age 35 among males who lived in a fraternity house.

Table 3.

GEE logistic regression assessing the association between involvement in fraternities and sororities (ages 19-24) and SUD symptoms at age 35.1

| Males College attendance and fraternity/sorority involvement (ages 19-24) |

Model 1 Two or More Alcohol Use Disorder Symptoms (age 35) 2 AOR (95% CI) |

Model 2 Two or More Cannabis Use Disorder Symptoms (age 35) 2 AOR (95% CI) |

Model 3 Two or More Other Drug Use Disorder Symptoms (age 35) 2 AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Active member in frat. (frat. resident) | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Active member in frat. (non-resident) | .667 (.431, 1.03) | .590 (.264, 1.31) | 1.54 (.510, 4.66) |

| Attended college (not in frat.) | .627 (.441, .892)** | .578 (.301, 1.11) | .984 (.357, 2.71) |

| Never attended college | .611 (.408, .916)* | .555 (.264, 1.16) | 1.34 (.459, 3.93) |

|

| |||

| 3 n = 3,644 | 3 n = 3,739 | 3 n = 3,594 | |

| Females College attendance and fraternity/sorority involvement by sex (ages 19-24) |

Model 4 Two or More Alcohol Use Disorder Symptoms (age 35) 2 AOR (95% CI) |

Model 5 Two or More Cannabis Use Disorder Symptoms (age 35) 2 AOR (95% CI) |

Model 6 Two or More Other Drug Use Disorder Symptoms (age 35) 2 AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Active member in sor. (sor. resident) | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Active member in sor. (non-resident) | .689 (.412, 1.15) | .433 (.116, 1.61) | 2.58 (.543, 12.2) |

| Attended college (not in sor.) | .634 (.400, 1.00) | .767 (.261, 2.25) | 3.85 (.957, 15.4) |

| Never attended college | .539 (.325, .894)* | .968 (.303, 3.08) | 5.88 (1.38, 25.0)* |

|

| |||

| 3 n = 4,946 | 3 n = 5,122 | 3 n = 4,892 | |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

AOR = adjusted odds ratio

Note that results using GEE logistic regression (i.e., XTGEE) or the regular logit option (i.e., logit) stratifying by an individual time point will produce identical results.

Each model (1-6) included age 18 controls for the following: cohort year at baseline,, race/ethnicity (i.e., White, Black, Hispanic, Other), parental education (i.e., at least one parent with a college degree vs. neither parent has a college degree), U.S. Census geographic region (i.e., Northeast, Midwest, South and West), metropolitan statistical area (i.e., large MSA, other MSA, and non-MSA), truancy (i.e., skipped school in past-month versus not), high school grades (i.e., C+ or lower versus B- or higher), and frequency of evenings out with friends (i.e., 3 times or more during a typical week versus 2 times or less), 30-day cigarette use, past two-week binge drinking, past-year marijuana use, past-year illicit drug use other than marijuana, and past-year nonmedical use of prescription drugs.

Sample sizes vary due to missing data on the outcome of interest. Note that SUDs are only measured at age 35, and only respondents who completed surveys at age 35 could be included into the analyses. All models use weights to account for attrition at age 35.

Figure 2.

Observed differences in two or more alcohol use disorder symptoms at age 35 based on fraternity/sorority involvement, college attendance, and sex

1Percentages were calculated using weights to account for attrition at age 35; 95% confidence intervals are based on standard errors obtained using Taylor linearization.

2The available sample size (unweighted) at age 35 was 9,060 respondents who answered questions related to AUDs at age 35 and fraternity/sorority status during college years.

Discussion

The present study offers new evidence based on national longitudinal data that young adult men who belong and reside in fraternities during college engage in significantly higher rates of binge drinking and marijuana use during young adulthood and early midlife relative to their college peers and same-age non-students. Similarly, such fraternity involvement was associated with significantly greater odds of experiencing AUD symptoms during early midlife, controlling for numerous adolescent sociodemographics and behaviors, including binge drinking. Indeed, approximately 45% of young adult men who resided in fraternities had two or more AUD symptoms in early midlife (age 35), reflecting criteria for mild (or more severe) AUD, far exceeding the AUD rate for their peers and the prevalence of AUD among similar aged U.S. adults [14,24].

The present findings differ somewhat from earlier findings from a smaller single university study indicating that differences in heavy drinking among fraternity and sorority members relative to nonmembers during college were no longer apparent in the years following college [1,6]. The discrepancies in findings between the present study and earlier work could be partially attributed to the tremendous variation in substance use rates between individual colleges, for example, binge drinking rates ranged from 0% to 70% across individual U.S. colleges [15]. Thus, our findings provide new evidence based on national longitudinal data about the long-term associations between residential fraternity experience during college and later AUD symptoms, indicating that for many, this experience is not a developmental disturbance without lingering effects, and instead a potential sensitive period that sets the stage for long-term difficulties [16–18]. Although the present study found similar results among sorority members, males who lived in a fraternity house had significantly higher rates of binge drinking across the seventeen year period when compared to all other subgroups, and significantly higher rates of adulthood AUD compared to all other subgroups except non-residential fraternity members. These findings suggest new approaches may need to be considered such as selective and indicated preventive interventions highlighting fraternity residents who have successfully obtained treatment for AUD-related problems and sharing relevant resources for interested members, including correspondence and gatherings with fraternity alumni.

The current study contained numerous features that help address key gaps in the relevant literature. First, the study includes national samples of multiple cohorts of high school seniors who were followed longitudinally over 17 years from late adolescence to early midlife, allowing for an assessment of both college and non-college students. Second, the samples of high school seniors attended a wide range of colleges and universities, allowing us to generalize our findings beyond a single institution. Finally, the focus of the current study extends beyond consideration of only alcohol use to include cigarette smoking, nonmedical prescription drug use, marijuana use, other illicit drug use, and adult SUD symptoms.

Limitations should be taken into account while considering implications of the findings. First, the study did not include a sex-specific measure of binge drinking (i.e., 4+ drinks for females, 5+ for males) and three of eleven DSM-5 SUD criteria. Formal DSM-based diagnoses could not be established given the study methods; nonetheless, SUD estimates closely resemble other recent national estimates [14,24–26]. Second, there are important subgroups of the U.S. adolescents missing such as high school students who dropped out of high school, were home-schooled, or were absent on the day of data collection [9,14,20,38]. Third, while prior work has found that MTF self-report measures have been found to be reliable and valid, studies on youth suggest that misclassification and under-reporting of sensitive behaviors such as substance use can occur [9,20,27,28,39,40]. Finally, although we attempt to correct for differential attrition, it is likely that our findings do not pertain to those engaged in substance use resulting in severe impairment, indicating that our findings may reflect conservative estimates of rates and associations regarding substance use.

In conclusion, the current study indicates young adult men who reside in fraternities during college engage in significantly higher rates of binge drinking during and after college, even when including controls for potential selection effects. College prevention efforts such as bystander programs should be aimed at active fraternity and sorority residents based on the significant increases in substance use among these high-risk students during college. Furthermore, nearly half of young adult men who resided in fraternities reported multiple AUD symptoms following young adulthood and future research is needed to examine potential mechanisms that could be driving this association and whether these higher rates continue into later adulthood. Taken together, these findings indicate fraternity residents should be considered for selective and indicated SUD prevention efforts during and after college.

Supplementary Material

Implications and Contribution.

The present study provides new evidence that fraternity residence is associated with heavy substance use among young adult males well beyond the college years, resulting in greater odds of alcohol use disorder symptoms in early midlife. These findings reinforce the importance of selective and indicated substance use prevention efforts among fraternity males during and after college.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse [R01DA001411, R01DA016575, R01DA031160, R01DA036541, R01DA037902, and R01DA043691] and National Cancer Institute [R01CA203809], National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Cancer Institute, or the National Institutes of Health. The sponsors had no additional role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. There was no editorial direction or censorship from the sponsors. The Monitoring the Future data were collected under research grants R01DA001411 and R01DA016575, and the work of the third author on this manuscript was supported by these grants and R01DA037902. For the first and second authors, work on this manuscript was supported by research grants R01DA031160, R01DA036541, R01DA043691, and R01CA203809. The authors would like to thank Deborah Kloska for her help regarding sample and analytic decisions.

Contributor Information

Sean Esteban, University of Michigan, Center for the Study of Drugs, Alcohol, Smoking and Health, School of Nursing, Institute for Research on Women and Gender and, Substance Abuse Research Center, Ann Arbor, MI, USA 48109

Philip Veliz, University of Michigan, Center for the Study of Drugs, Alcohol, Smoking and Health, School of Nursing, Institute for Research on Women and Gender, Ann Arbor, MI, USA 48109

John E. Schulenberg, University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research and, Department of Psychology, Ann Arbor, MI, USA 48106-1248

References

- 1.Bartholow BD, Sher KJ, Krull JL. Changes in heavy drinking over the third decade of life as a function of collegiate fraternity and sorority involvement: a prospective multilevel analysis. Health Psychol. 2003;22:616–626. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.6.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell R, Wechsler H, Johnston LD. Correlates of college student marijuana use: results of a US national survey. Addiction. 1997;92:571–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capone C, Wood MD, Borsari B, Laird RD. A prospective examination of relations between fraternity/sorority involvement, social influences and alcohol use among college students: Evidence for reciprocal influences. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21:316–327. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCabe SE, Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Kloska DD. Selection and socialization effects of fraternities and sororities on U.S. college student substance use: a multi-cohort national longitudinal study. Addiction. 2005;100:512–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park A, Sher KJ, Krull JL. Risky drinking in college changes as fraternity/sorority affiliation changes: a person-environment perspective. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22:219–29. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sher KJ, Bartholow BD, Nanda S. Short- and long-term effects of fraternity and sorority membership on heavy drinking: a social norms perspective. Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15:42–51. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.15.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larimer ME, Anderson BK, Baer JS, Marlatt GA. An individual in context: predictors of alcohol use and drinking problems among Greek and residence hall students. J Subst Abuse. 2000;11:53–68. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)00020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wechsler H, Kuh G, Davenport AE. Fraternities, sororities and binge drinking: results from a national study of American colleges. NASPA J. 2009;46:395–416. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Miech RA, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use 1975-2016: Volume II College Students and Adults Ages 19-55. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Institute for Social Research; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulenberg JE, Maggs JL. A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002;14:54–70. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Historical and developmental patterns of alcohol and drug use among college students: Framing the problem. In: White HR, Rabiner D, editors. College Drinking and Drug Use. New York: Guildford; 2012. pp. 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulenberg J, Maggs JL, Long SW, et al. The problem of college drinking: insights from a developmental perspective. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:473–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The NSDUH Report: Nonmedical Use of Adderall® among Full-Time College Students. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center, for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeykens B, Castillo S. Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college: a national survey of students at 140 campuses. JAMA. 1994;272:1672–1677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rauer AJ, Schulenberg JE. Developmental disturbances. In: Bornstein MH, Arterberry M, Fingerman K, Lansford JE, editors. The SAGE encyclopedia of lifespan human development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulenberg JE, Maslowsky J. Contribution of adolescence to the life course: What matters most in the long run? Res Hum Dev. 2015;12(3-4):319–326. doi: 10.1080/15427609.2015.1068039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schulenberg JE, Maslowsky J, Jager J. Substance use and abuse are developmental phenomena: Conceptual and empirical considerations. In: Fitzgerald HE, Puttler LI, editors. Developmental Perspectives on Alcohol and Other Addictions over the Life Course. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. The Monitoring the Future Project after Four Decades: Design and Procedures, Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper No82. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research University of Michigan; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use 1975-2015: Volume I, Secondary School Students. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Institute for Social Research; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCabe SE, Veliz P, Schulenberg JE. Adolescent context of exposure to prescription opioids and substance use disorder symptoms at age 35: a national longitudinal study. Pain. 2016;157:2173–2178. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCabe SE, Veliz P, Wilens TE, Schulenberg JE. Adolescents’ prescription stimulant use and adult functional outcomes: A national prospective study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56:226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME, Kloska DD, et al. Substance use disorder in early midlife: A national prospective study on health and well-being correlates and long-term predictors. Subst Abuse. 2016;9(S1):41–57. doi: 10.4137/SART.S31437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Tulshi DS, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grant BF, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:39–47. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasin DS, Kerridge BT, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder, 2012-2013: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:588–599. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15070907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrison L, Hughes A. The validity of self-reported drug use: improving the accuracy of survey estimates. NIDA Res Monogr. 1997;167:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM. Issues of validity and population coverage in student surveys of drug use. NIDA Res Monogr. 1985;57:31–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harford TC, Muthén BO. The dimensionality of alcohol abuse and dependence: A multivariate analysis of DSM-IV symptom items in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:150–157. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muthén BO. Psychometric evaluation of diagnostic criteria: application to a two-dimensional model of alcohol abuse and dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;41:101–112. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson CB, Heath AC, Kessler RC. Temporal progression of alcohol dependence symptoms in the U.S. household population: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:474–483. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merline A, Jager J, Schulenberg J. Adolescent risk factors for adult alcohol use and abuse: stability and change of predictive value across early and middle adulthood. Addiction. 2008;103(Suppl 1):84–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE, O‘Malley PM, Johnston LD, Bachman JG. Adolescents’ reported reasons for alcohol and marijuana use as predictors of substance use and problems in adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72:106–116. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th. Arlington, Virginia: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Smith SM, et al. Nosologic comparisons of DSM-IV and DSM-5 alcohol and drug use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76:378–388. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanley JA, Negassa A, Edwardes MD, Forrester JE. Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: an orientation. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:364–375. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach Biometerics. 1988;44:1049–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaughn MG, Salas-Wright CP, Kremer KP, et al. Are homeschooled adolescents less likely to use alcohol tobacco and other drugs? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;155:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morral AR, McCaffrey DF, Chien S. Measurement of adolescent drug use. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35:301–309. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10400013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.West BT, McCabe SE. Alternative approaches to assessing nonresponse bias in longitudinal survey estimates: An application to substance use outcomes among young adults in the U.S. Am J Epidemiol. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww115. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.