Introduction

The question of whether to offer a research participant’s genomic results to family members, including after the participant’s death, is a difficult and pressing issue. Research projects sequencing probands with life-limiting conditions such as fatal cancers will predictably encounter this issue, as will projects that archive data and specimens for potential reanalysis long into the future. In Fall 2015, we published groundbreaking recommendations for the return of adult and pediatric research results to family members, including after the death of the research participant.1 We published those consensus recommendations as part of a journal symposium issue growing out of a project funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and offering multiple papers on these issues.2 The project additionally collected data on stakeholder attitudes and preferences,3 and then began piloting return of results to relatives.

Researchers and commentators have begun to address the complex issues raised by return of results (defined here to include return of incidental or secondary findings) to relatives,4 including the relatives of pediatric research participants.5 However, largely missing from this literature is pragmatic guidance, offering a process and toolkit for addressing return of results to family members, including the documents needed to progress systematically through this complicated and multi-actor process. This paper aims to fill that gap.

Developing tools for genomics implementation is a crucial part of successful translation of genomics into clinical care.6 Our project has been part of the Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research (CSER) Consortium created by NIH to develop best practices for integrating genome and exome sequencing into clinical care. Our toolkit of core documents can aid research projects by offering a place to start in developing their process and documents for sharing results with family members. While this publication offers written tools, projects can adapt these tools to develop a process that may include written, telephone, face-to-face, and computer-aided communications.

Using our previously published recommendations as the starting point, this paper offers the first communications toolkit for return of results to relatives. Our earlier recommendations urged genomics researchers to anticipate the possibility of relatives requesting a participant’s results, and to clarify for prospective recipients how the research project plans to handle such requests. We recommended that, “If there is any potential for return of such results to relatives, the researchers should ask participants their preferences for sharing results with relatives, including after the participant’s death, and should invite participants to identify their preferred representative to make decisions about relatives’ access to their genomic results” when the participant is unable to do so or deceased.7 Inviting participants to name a preferred representative can guide later identification of the person to make decisions about relatives’ access to the participant’s results when the participant cannot decide for him– or herself because of decisional incapacity or death. As in our prior paper, we refer to that person here as the participant’s Representative, “the person legally authorized to access a participant’s results.”8

Our recommendations stated that researchers are not obligated to return a participant’s results to relatives, but may decide to participate in that return. We recommended that if researchers decide to participate in return to relatives, the researchers should generally adopt a passive disclosure policy of responding to relatives’ requests, instead of an active policy of initiating disclosure to relatives. However, the majority of our group concluded that in exceptional cases (discovery of a highly pathogenic and actionable variant that a relative is likely to carry), the researcher “may be ethically justified in actively reaching out” to the relative.9

We add additional detail in our earlier recommendations paper, and we elaborate below on how to put these recommendations into practice. Together, our previously published recommendations and the toolkit developed here can aid research design and genomics implementation. This paper presents tools that research studies can use in research with adult and pediatric participants, both before and after the participant’s death.

I. Method

Funded by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) at NIH, our project conducted empirical research10 to undergird a normative process of developing the consensus guidelines that were published in Fall 2015.11 Those guidelines were the product of work led by one of the project’s principal investigators (PIs) (S. M. W.) with participation from the other PIs (G. P. and B. A. K.) and the project’s multidisciplinary Working Group. After completing work on those guidelines, we undertook a process of collecting and analyzing documents and guidance available to researchers for return of results to family, in order to create a basic toolkit of documents to help researchers address this issue. We canvassed the published literature as well as tools available through the website of the CSER Consortium, in which this project has participated.12

At the same time, our project has undertaken a process of piloting return of results to family members. This has required designing a practical process for the family members of deceased probands with pancreatic cancer who have participated in Mayo Clinic’s pancreatic cancer SPORE, a biobank supported by NCI. That pilot process and data collection is under way, but required the creation of a full set of documents and communication tools for the families involved. The toolkit presented here benefited from design of that pilot project, though the tools offered in this paper are not identical to those tailored for the pilot.

After preliminary research and analysis, the Working Group met in May 2015 to discuss potential tools to create for investigators, Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), biobanks, and research institutions in order to facilitate the ethical and pragmatic return of research results to family members. After further research and drafting of potential products, the Working Group met again by telephone in December 2015 and in person in May 2016. Throughout the preparation of this paper we continued research on the literature and relevant consent models.13 This paper and appendices were subsequently finalized by circulating written drafts for comments and approval.

II. Results

Through careful consideration of the ethics, law, and practical issues surrounding return of research results to family members, this paper presents tools that can be adapted to the many contexts in which genomics research is performed. It is important to emphasize that the tools we offer are a starting point — research projects will need to adapt these depending on their research design and population, the specific genomic results being generated (including potential family interest in both “positive” results showing the presence of a pathogenic variant and “negative” results showing the absence of a variant), and the context for their research.14 Part of customizing these forms will be deciding when to reach out to the participant’s Representative to alert them to their responsibilities if a family member requests results; the processes outlined below include alerting the Representative once that person is identified, but some research projects may prefer to wait until a relative’s request arises. In addition, these forms may require modification to adjust reading level in order to optimize readability and comprehension, depending on the population. Our goal is to outline the flow of decisions and the key elements needed at each step, as further indicated by the “Points to Consider” included for the research team at the top of each form.

These forms are meant to help structure a larger communication process. Much as consent forms are only part of a larger consent process, the document templates offered here are intended to aid and anchor a communications effort that may include in-person, telephone, computer-aided, and other means of contact and counseling. While we offer here a set of forms, the research team for a particular project may decide that some of these processes are best handled orally, with written or electronic records created of the decisions made. The set of forms we offer can serve as a starting point for the research team in designing a process tailored to the specific research project.

Finally, we note that a family request for research participant results may arise after the end of the research project generating those results. Throughout this paper we address the responsibilities and options that fall on the researcher and research team to anticipate family requests and plan for them. A number of published papers have urged that researcher duties to return results should not continue past the end of research funding.15 Because family members may request results at any time, including after research funding has ended, researchers anticipating family requests should work with their institution to plan which office or individuals at the institution should be responsible for handling family requests after the conclusion of the research generating the findings. Context will determine the options, which may involve more than one entity at the institution, including the relevant biobank (if any), genomics laboratory, and records office.

This paper proceeds in four parts, addressing four different basic scenarios that researchers and institutions may encounter: return of results to family when there is (1) a living adult research participant, (2) a deceased adult participant, (3) a living pediatric participant, or (4) a deceased pediatric participant. Each part references the template documents we offer in the Appendices.

Table 1 enumerates the 6 template documents in the Appendices that offer a starting point for research projects considering return of results to family members.

Table 1.

The 6 templates created to address return of research results to family.

| Type of research | Appendix | Template document |

|---|---|---|

| Adult research | Appendix A | Adult Participant Statement of Preferences on Return of Results to Family Members and Designation of a Representative |

| Adult research | Appendix B | Guidance Letter for Representative |

| Adult or pediatric research | Appendix C | Consent Form for Family Member to Receive Participant’s Research Results |

| Adult or pediatric research | Appendix D | Letter to Family Member to Share or Confirm Research Results |

| Pediatric research | Appendix E | Guidance for Parents/Guardian Considering Family Access to Child’s Research Results |

| Pediatric research | Appendix F | Child/Adolescent Participant Statement of Preferences on Return of Results to Family Members |

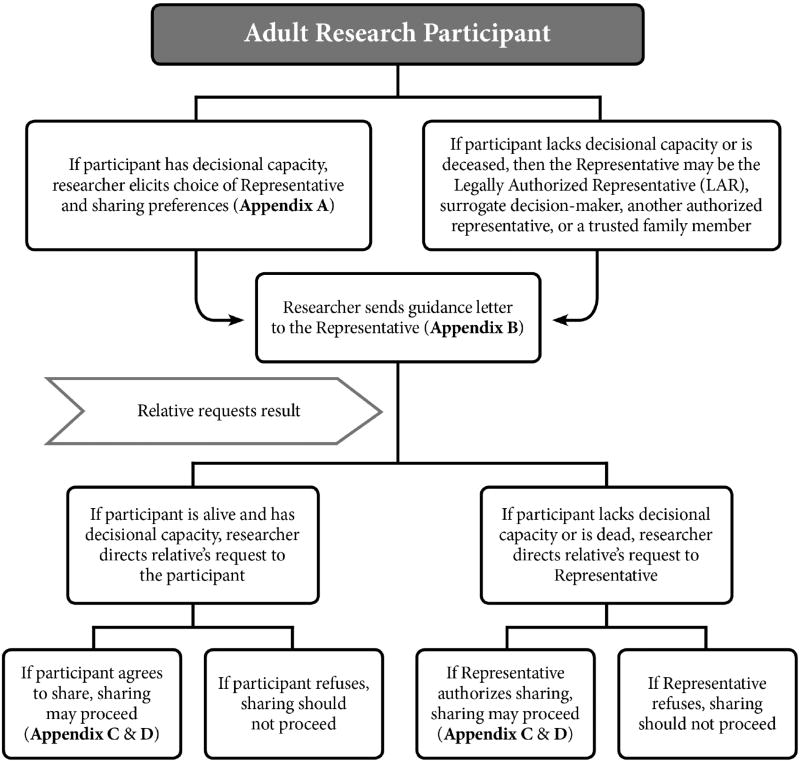

We first address return of results to relatives when the research participant is an adult. Figure 1 summarizes the recommended roadmap for returning results to relatives when the adult participant is living or is deceased.

Figure 1.

Recommended roadmap for returning research results to family members of adult research participants, both living and deceased.

1. Adult Research Participant — Living

A. STATEMENT OF PARTICIPANT PREFERENCES ON RETURN TO FAMILY AND REPRESENTATIVE

The process of enrolling eligible adults in a research study customarily starts with informed consent. During this consent process, researchers should discuss with the prospective participant the project’s policy on sharing results with family members, explaining how requests from family members will be handled and whether the researchers in some circumstances may initiate an offer of results to relatives without such a request (as discussed below in section D.). As noted above, our project’s prior recommendations urged eliciting participant preferences on whether to offer results to family members as well as participant designation of a preferred Representative to make decisions about sharing results if and when the participant cannot do so due to incapacity or death. Researchers should elicit participant preferences on sharing with family and choice of a Representative; a suggested form is presented in Appendix A. However, the form should make clear that while the participant is alive and has decisional capacity, the participant (not the Representative) will make decisions about family access to results.

In Fall 2015, Amendola and colleagues published a return of results authorization form used in their NEXT Medicine Study, taking a different approach.16 That form allows the participant to designate a recipient for results if the participant dies or becomes incapacitated before all results have been returned. Their form is similar to a sample form from the Multi-Regional Clinical Trials (MRCT) Center of Harvard and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, which authorizes a third party to receive research results.17

In contrast, our form is not just an authorization for a designated individual to receive results not yet returned to the participant, but rather an authorization for the Representative to potentially receive all results and to decide on other relatives’ access to results. After the participant’s death or loss of decisional capacity, our form allows the Representative to share the participant’s results if other family members seek out the participant’s results and the participant approved of sharing. Our form also notifies the participant that even if the participant does not want the Representative to share the results, other applicable law may trump this decision (e.g., HIPAA18 or state law). Additionally, the form alerts the participant that in rare circumstances, researchers may reach out directly to family members to initiate an offer of results. However, under our project’s previously published guidelines, this active disclosure will be limited to cases in which the research result poses a high and imminent health risk that can be reduced or eliminated if the relative is informed.

Also unlike the form from Amendola and colleagues, our form does not expire once the participant him- or herself receives results. An expiring authorization form could shut down family access to a result that the participant received but felt too ill to share. Empowering a Representative to share all results avoids the problem and allows the Representative to consider sharing even results generated by analyses undertaken after the participant’s death.

B. GUIDANCE FOR THE REPRESENTATIVE ON RETURN OF RESULTS TO RELATIVES

If the participant completes the statement of preferences form and designates a Representative (Appendix A), the researcher should provide guidance to the designated individual. The researcher can send a letter explaining the Representative’s role and what to do if the participant becomes decisionally incapacitated or dies (Appendix B). Our template letter informs the Representative that relatives seeking the participant’s genetic results after the participant’s loss of decisional capacity or death will be directed to the Representative. The letter then addresses how the Representative should decide about family access; the participant who has completed a statement of preferences (Appendix A) will have provided strong grounds for the Representative to follow those preferences. Finally, the letter notes that in rare circumstances, researchers may reach out directly to family members if they discover a result that poses a high and imminent health risk that can be reduced or eliminated if the family member is informed — an approach that the majority of our group supported in our prior recommendations paper.19 The letter notes that in these rare circumstances, the researchers or institution will first work with the Representative to facilitate sharing this result, but may reach out directly to family members in some situations to prevent harm (see section D. below).

If a family member comes forward requesting the participant’s research result, the living adult participant should be contacted so the participant can decide whether to authorize sharing. While the participant can proceed to share the result with the family member, the participant may request help from the researcher. If the researcher or research team provides assistance, they should first confirm that the family member agrees to receive the result. (Appendix C) The result can then be communicated by a knowledgeable professional equipped to counsel the family member on the result’s implications and on the availability of genetic testing to ascertain the relative’s genetic status, such as a medical geneticist or genetic counselor. This professional can then follow up with a letter confirming the communicated result, so that the family member can share the letter with his or her clinician or with other family members (Appendix D). The letter should provide the research result, state the potential health implications for the family member, and indicate how to seek further counseling and genetic testing.

One issue that may arise is whether researchers should return a participant’s research results to family members when those results are from a lab that is not CLIA-certified. Some group members thought results should not be returned unless the testing was performed (or the results were confirmed) in a CLIA-certified lab. However, the debate continues about whether researchers can return research results from a lab without such certification.20 Although the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have indicated that only results generated in CLIA-compliant laboratories should be considered for return, there is a strong argument that other laboratories should be able to offer important research results with an explicit caution that no clinical action should take place until the results have been confirmed in a CLIA-compliant setting.21 In the context of return of results to relatives, we recommend that the proband’s results be verified in a CLIA-compliant lab if possible before those results are communicated to family members. If research results are offered without such verification that should be clearly stated. In any case, relatives receiving the participant’s results should not act until they themselves have been tested and received clinically verified results of their own, as noted in the family letter in Appendix C.

C. ADULT PARTICIPANTS LACKING DECISIONAL CAPACITY

Some participants will be incapable of designating a Representative and stating preferences regarding family sharing because they lack decisional capacity. Performing genomic research in this context can raise challenges.22 In these cases, the participant’s Representative may be the participant’s Legally Authorized Representative (LAR), surrogate decision-maker, another authorized representative, or a trusted family member.23

Once this Representative is determined, the researchers should send guidance to inform the Representative of their role (Appendix B). Our suggested form clarifies for the Representative how to make decisions on sharing results with relatives, in keeping with the recommendations of our consensus paper:24

If the research participant agreed to sharing results with family members, this provides strong grounds for the Representative to permit access.

If the participant stated a preference not to share, this provides strong grounds for the Representative to refuse access.

If the participant was silent on sharing results with family members, the Representative should balance the participant’s privacy and personal interests against the interests of relatives in receiving the genetic results.

We noted in our consensus paper that this suggested decisional approach differs from the approach recommended for surrogate decision–makers making a treatment decision for decisionally incapacitated adults.25 In decisions about treatment, the surrogate is customarily encouraged to (1) follow the patient’s express wish if known; or (2) if no express wish is available, to exercise substituted judgment to decide as the patient would have decided, based on what is known of the patient’s preferences; or (3) if the surrogate lacks adequate information to use these standards, to decide in the patient’s best interests. Our Working Group decided that the question of sharing results within the family called for a simpler and more flexible standard that considered participant preferences, but when those were unknown, encouraged the Representative to balance the participant’s privacy and personal interests with the needs of family members.

If application of these standards leads the Representative to conclude that sharing is appropriate, we offer two forms to aid that process. Appendix C strives to ensure that the family member agrees to receive the result. Appendix D then provides the result in written form to support accuracy and allow the family member to share the document with his or her clinician. While use of these forms can help structure the communication process, some families may find the use of such forms to be too formal and may prefer oral communication. We nonetheless offer these forms to help the research team consider the issues involved and plan how best to handle them. In addition, the Representative may ask for assistance from the research team in communicating the result to the family member. In that case, the research team may find these forms useful to document the family member’s agreement to receive the result and the nature of the result communicated to that family member.

D. RARE CIRCUMSTANCES IN WHICH RESEARCHERS MAY INITIATE RETURN TO RELATIVES

Our published consensus recommendations urged that return of results to family members should generally be in response to a family request rather than initiated by the researcher. However, most Working Group members agreed that a researcher may actively reach out to a participant’s relative to offer research results in the rare case in which the researcher finds “highly pathogenic and actionable variants that the relative is likely to carry, and whose disclosure is highly likely to avert imminent harm.”26 Both the Representative authorization form and guidance letter (Appendix A and B) alert the participant and Representative to this possibility. If this exceptional circumstance arises, the researcher should first try to work with the participant (if alive and decisionally capable) or alternatively with the Representative to offer the result to the relative. If the participant or Representative permits sharing, then the researcher can offer a family consent form and letter to the participant or Representative to facilitate sharing the result with the family member (Appendix C and D).

However, if the participant or Representative declines to reach out to the relative with this urgent result, then the researcher should seek an ethics consultation. If deemed appropriate, the researcher may go ahead and contact the relative to seek their agreement to receive the result (Appendix C) and then to communicate the result if the relative agrees (Appendix D).

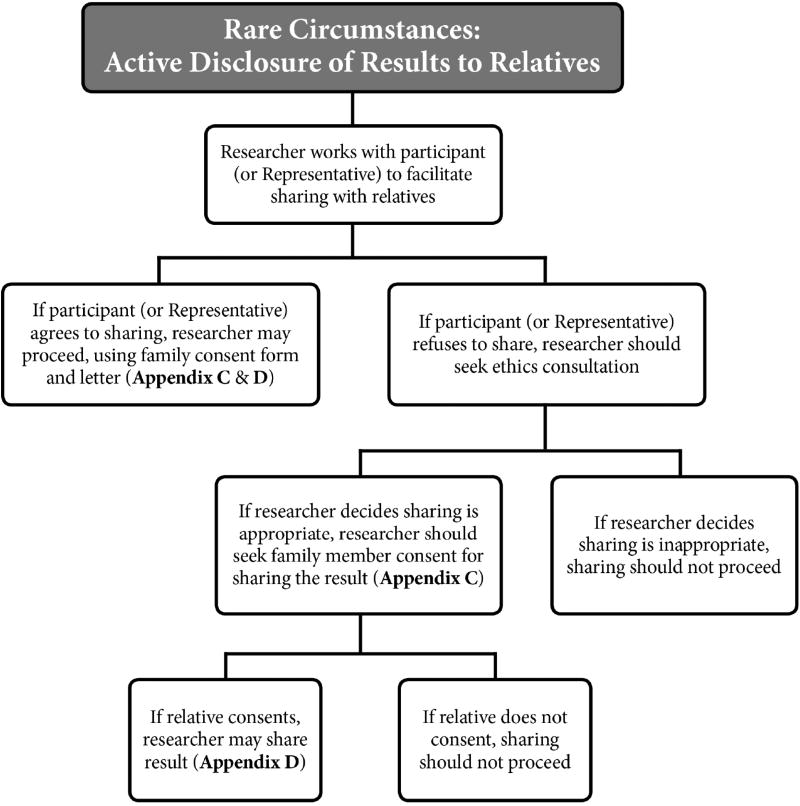

Figure 2 provides a roadmap for researchers to follow in these rare circumstances. This figure is applicable to both adult and pediatric research, both before and after the participant’s death; in pediatric research, the researchers will work with both the parents/guardian as Representative and the child (if alive and capable of assent). (See sections 3.B. and 4.A. below.)

Figure 2.

Recommended roadmap for rare circumstances justifying researcher-initiated return of results to family.

2. Adult Research Participant — Deceased

After the death of the participant, the Representative acts as the gatekeeper to the participant’s research results. The researcher should refer family access requests to that individual. The Representative should apply the decisional standards outlined above and in our prior recommendations paper — give weight to the participant’s preferences on sharing, and if the participant has provided no guidance on sharing, balance the participant’s privacy and personal interests against the interests of relatives in receiving the genetic results. (See section 1.C. above.) If relatives seek the participant’s results and the participant authorized sharing the research results, then the Representative has strong support to share the results. If the Representative authorizes the sharing, the researcher can offer to provide them with a family consent form and letter explaining the result (Appendix C and D), although some Representatives will choose to proceed more informally.

A. NO REPRESENTATIVE AUTHORIZATION FORM

If the participant did not complete the form designating a Representative, the deceased participant’s Representative may be the participant’s Legally Authorized Representative (LAR) or surrogate decision-maker, another authorized representative, or a trusted family member; state law may clarify who can serve in this capacity. Once the Representative is determined, the researcher should share guidance on that role with the Representative (Appendix B). As discussed above, if the participant did not indicate preferences on sharing results with family members, the Representative should balance the participant’s privacy and personal interests against the interests of relatives. If the Representative determines that sharing is appropriate, researchers can provide the Representative with a family consent form and letter explaining the result (Appendix C and D).

B. RARE CIRCUMSTANCES IN WHICH RESEARCHERS MAY INITIATE RETURN TO RELATIVES

As noted above, in rare cases, researchers may discover a highly pathogenic and actionable variant whose disclosure to relatives is highly likely to avert imminent harm. In these cases, if the participant or Representative agrees to share, then they or the researchers can offer the result to relatives (Appendix C and D). If the participant or Representative refuses to share the result, the researcher should seek ethics consultation for guidance on whether the researcher should nonetheless offer the result to relatives.

When researchers are offering results to relatives, they should ascertain whether the relative agrees to receipt of the result (Appendix C) and can adapt the letter we suggest to confirm the result communicated (Appendix D).

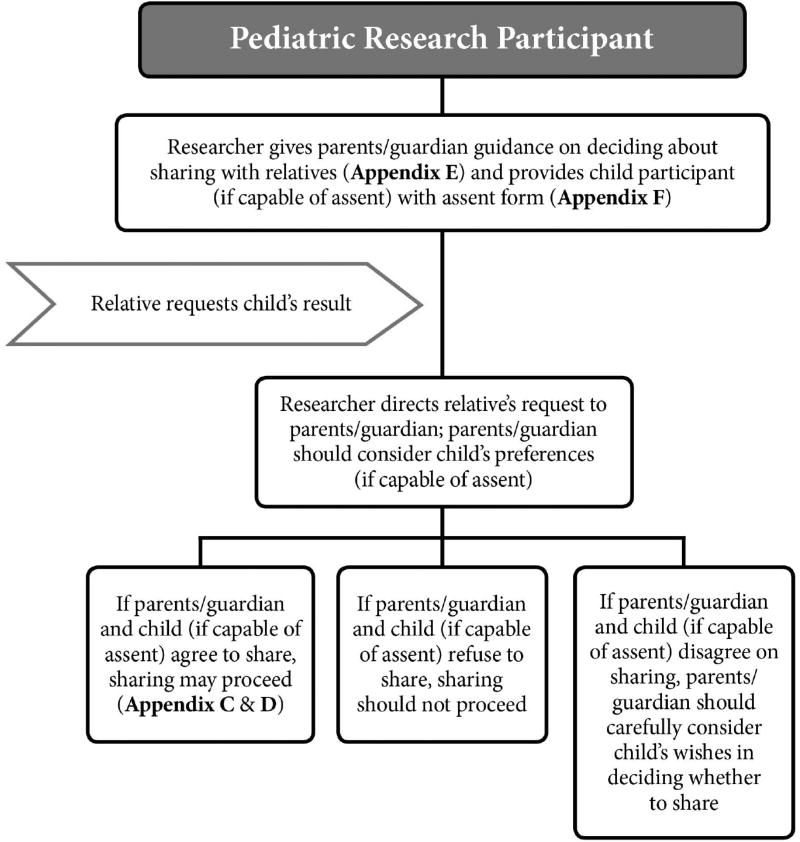

We next consider return of results to relatives when the research participant is a child or adolescent. Figure 3 summarizes the recommended roadmap for returning results to relatives when the pediatric participant is living or is deceased.

Figure 3.

Recommended roadmap for returning research results to family members of pediatric research participants, both living and deceased.

3. Pediatric Research Participant — Living

A. PARENTS/GUARDIAN’S REPRESENTATIVE GUIDANCE & PEDIATRIC PARTICIPANT ASSENT

Child and adolescent research participants present additional challenges.27 Parents or a guardian must grant permission for the child’s participation28 and the child, if capable, must assent to participate in the study.29 Results that implicate adult-onset diseases or that have reproductive significance raise additional ethical issues, because the child may receive no direct benefit from receiving the results, but parents and family members may benefit.30

During the permission and assent processes, researchers should discuss the project’s policies on return of results to family with the child participant (a term used here to include child and adolescent research participants) and the parents/guardian, explaining how researchers will handle requests from family members as well as whether the researchers may initiate disclosure of results to relatives in the absence of such a request. In most cases, the parents/guardian providing permission for the child’s participation in research will also serve as the child’s Representative to make decisions about sharing results with relatives while considering the child’s preferences (if any). Accordingly, we provide no form in which the child states a preference for who should act as Representative; nor do we provide a form asking the parents/guardian who should act as the Representative if they cannot. However, these issues may arise in some studies and some individual cases. Researchers may then need to consider eliciting the child’s preferences on who should serve as Representative and can consider the format we recommend for eliciting this preference from adults (Appendix A). When researchers need to consider asking the parents/guardian who they feel should serve as the Representative if they cannot, the researchers again can consider adapting the form we recommend for eliciting the adult participant’s preference on Representatives (Appendix A). In cases of conflict between a child capable of assenting and parents/guardian on who should serve as the child’s Representative, ethics and legal consultation may be needed.

The parents/guardian serving as the child’s Representative should be alerted that a family member may seek results. The form we recommend to orient parent/guardian Representatives to their responsibilities may be helpful (Appendix E). While this guidance form provides much of the same information that would be provided to the Representative of an adult participant, this letter addresses issues that are unique to pediatric genomic research, such as the role of participant assent. The letter also alerts the Representative to the ongoing debate about whether researchers should disclose genomic results that pertain to adult-onset diseases,31 while acknowledging that the researchers will determine whether to return these results within the study.

In addition, we offer a form that can be shared with a child or adolescent capable of assent, in order to orient them to the sharing question and to elicit their preferences on sharing their results with family members (Appendix F). Similar to the form for adult participants (Appendix A), this form provides general information about relatives’ potential desire for the child’s results. The form also notes that the child’s parents/guardian will determine whether to share those results until the child reaches the age of majority, but should consider the child’s preferences. The form states that when the child reaches the age of 18, the child will control access to their own results. Note that if the child is unable to assent due to age, maturity, or psychological state, then researchers should not provide this guidance form to the child and instead should rely on the decision of the parents/guardian to share the child’s results.

If a relative requests the participant’s results, the child’s Representative (usually the parents/guardian) should be contacted. As indicated in the guidance form for the child’s Representative (Appendix E), if the Representative and the child (if capable of assent) agree to share the result, sharing may proceed. In these cases, the child’s Representative may find helpful the two forms discussed above — the family consent form and letter to share the research result (Appendix C and D). However, if the child’s Representative and child (if capable of assent) both refuse to share, then sharing should not proceed.

A more difficult case will arise if the child’s Representative and the child participant disagree about whether to share research results. Appendix E advises the child’s Representative on the decisional approach our earlier consensus paper recommended.32 The parents/guardian (or other Representative) should carefully consider the child’s preferences if the child is capable of assent, has been informed of the issues, and has communicated a considered view on whether to share results with relatives. We noted that cases of disagreement in which a living child wishes to block family access to results will need ethics consultation.33

Another challenging scenario may arise if the participant’s parents disagree between themselves about sharing results with relatives. Parental disagreement over sharing will need to be addressed on a case-by-case basis, and researchers may need to seek ethics or even legal consultation.

B. RARE CIRCUMSTANCES IN WHICH RESEARCHERS MAY INITIATE RETURN TO RELATIVES

Again, exceptional cases may arise involving highly pathogenic and actionable variants whose disclosure to a family member is highly likely to avert imminent harm. The researcher should work with the parents/guardian and child (if capable of assent) to facilitate the return of the result. However, if the parents/guardian and child refuse to share, the researcher should seek ethics consultation. After the consultation, the researcher may still offer these results to the relative if offering is deemed appropriate. (See Figure 2.) The researcher can then use the forms we suggest to ground a process of notifying the relative of the option to receive the result and to seek the relative’s agreement to receive the result (Appendix C). If the relative agrees, the researcher may share the result with the relative and can use the form we offer to aid that process (Appendix D).

4. Pediatric Research Participant — Deceased

After the death of a pediatric participant, the parents/guardian as the child’s Representative customarily have control over family access to the child’s results, assuming they are alive and have decisional capacity. Investigators should direct family requests to the parents/guardian, who may then decide whether to share the result. If the parents/guardian elect to share the result and the child, while living and able to assent, approved of sharing, then sharing may proceed. If the parents/guardian do not wish to share and the child while alive also preferred not to share, then sharing should not proceed.

If the parents/guardian and child disagreed about sharing research results with family members, the parents/guardian should carefully consider the child’s preferences, especially if the child was informed of the issues and communicated a considered preference on sharing. Cases in which the child communicated a considered preference to block sharing with relatives may need ethics consultation.34

A. RARE CIRCUMSTANCES IN WHICH RESEARCHERS MAY INITIATE RETURN TO RELATIVES

As discussed above, exceptional cases may arise involving highly pathogenic and actionable variants whose disclosure to a family member is highly likely to avert imminent harm. In these unusual cases, the researcher may initiate return. As noted above in the case of adult participants, the researcher should first try to work with the parents/guardian as the child’s Representative to facilitate sharing. If the parents/guardian approve sharing and the child (while alive and capable of assent) did not object, then the researcher can proceed with the process of reaching out to the relative for agreement to receive the result (Appendix C). However, if the parents/guardian or the child (while alive and capable of assent) objects to sharing, the researcher should seek an ethics consultation. After the consultation, the researcher may still offer these results to relatives if offering the result is deemed appropriate. The researcher will then need to notify the relative of the option of receiving the result and seek the relative’s agreement to receive the result (Appendix C). If the relative agrees to receive the result, we offer a form that may be useful to support communication of the result (Appendix D).

III. Discussion

Our earlier consensus paper urged that genomics research teams routinely plan ahead to determine how they will handle family member requests for access to a participant’s results, including after the participant’s loss of decisional capacity or death.35 This counsels communicating to prospective participants how such requests will be handled. We emphasized in our earlier paper that researchers are not obligated to engage in the process of return of results to relatives, but may engage in this process.

Our earlier consensus paper urged that genomics research teams routinely plan ahead to determine how they will handle family member requests for access to a participant’s results, including after the participant’s loss of decisional capacity or death. This counsels communicating to prospective participants how such requests will be handled. We emphasized in our earlier paper that researchers are not obligated to engage in the process of return of results to relatives, but may engage in this process.

When researchers anticipate the possibility of sharing results with relatives, the researchers should elicit the adult participant’s preferences on sharing results and on who should serve as the participant’s Representative to make decisions about authorizing access to the participant’s results when the participant cannot make decisions him- or herself. Planning ahead also suggests alerting the chosen Representative to the issues raised by family requests for results, orienting that individual to his or her role if such a request occurs, and communicating to the Representative any substantive preferences on sharing that the participant communicated to the research team. As noted above, this may occur at the time the Representative is identified, in order to plan ahead. That person will then know their role if family requests arise at any time, including after the end of the research project. The Representative will also have the benefit of guidance if a family member requests results from them unbeknownst to the researchers. However, some research projects and institutions may decide to alert the Representative later, when the issue of return of results to relatives arises. If the participant is a child or adolescent, the planning process should include eliciting his or her preferences (if the minor is capable of assent) and alerting the Representative (who will usually be the parents or guardian) to the possibility that a family member may request results, orienting the Representative to this role, and communicating the child or adolescent’s preferences on sharing. Again, some research projects and institutions may decide to alert the child’s Representative to this role later, when the issue of sharing results with relatives arises.

The toolkit we offer in this paper will be valuable to researchers, their institutions, and their IRBs, as they plan for the possibility of a relative’s request for results. Planning for such a request and handling it responsibly can be complex — a number of individuals are potentially involved (including the research team, the participant, the participant’s Representative, the family member making the request, and others who may include the family member’s clinician and clinical genetic counselors). Further adding to the complexity is the length of time over which the issue can arise; a family member may make the request not only at any point in the research process, but also as long as the data are archived in a biobank or other facility, and potentially after the participant’s death. In addition, the wide range of health concerns that may prompt a request from a family member adds to the heterogeneity of scenarios that may arise. Finally, the possibility that researchers may find urgent genomic results that prompt the researchers themselves to consider initiating return adds to the complexity.

Faced with this complexity, the toolkit we offer here can significantly ease the burden of planning for how to handle family requests. The consensus recommendations we published earlier recommend a framework for approaching these issues, and the toolkit we offer here presents a starting point for operationalizing those recommendations. This starting point should reduce the person-hours and cost to the research team required to plan for handling the return of research results to relatives. Our recommendations and toolkit should facilitate planning at the time the protocol is formulated as to how these issues will be handled.

This advance planning should also allow the research team to secure more fully informed consent to participate in the study from prospective research participants, as the researchers will be able to tell prospective participants how family requests for access to results will be managed. The process we urge can also reassure participants that their preferences will be elicited regarding who should serve as their Representative and whether their results should be shared with family members.

Empirical results are beginning to emerge on individuals’ and family members’ preferences concerning sharing results within the family, both before and after the research participant’s death.36 Gathering data on preferences in a wide range of populations, asking how much deference should be accorded to the proband’s wishes about sharing, and exploring whether preferences vary by the type of genomic results at issue (for example, actionable cancer risk variants versus much less actionable variants predicting cognitive decline versus proband carrier status) will be important to further inform policy and practice on return of results to family. The policy and practices that we urge in our earlier consensus paper and operationalize in the toolkit presented here encourage respect for the range of participant preferences on sharing, deference to participant views on who should serve as their Representative to make sharing decisions when the participant cannot, and careful consideration of family members’ need for the results.

Conclusion

The goal of this paper is to offer pragmatic guidance and implementation tools to facilitate the ethical return of genomic research results to family members. Because the issue of sharing research results with relatives arises in ethically and legally complex scenarios and in a wide variety of research studies, these tools provide a much-needed starting point and source of guidance for researchers, IRBs, biobanks, and research institutions. This toolkit will help them to anticipate family requests for research results and facilitate orderly return of results without overburdening the research institution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute (NCI) and National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) grant 1R01CA154517 on “Disclosing Genomic Incidental Findings in a Cancer Biobank: An ELSI Experiment” (Gloria Petersen, Barbara Koenig, Susan M. Wolf, Principal Investigators). This work benefited from the investigators’ participation in the NIH-funded Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research (CSER) Consortium. The biobank at the Mayo Clinic SPORE in Pancreatic Cancer is supported by NIH grants P50CA102701 and R01CA97075. Additional support was provided by NIH grants P20HG007243 (Koenig); and U01HG006500, U19HD077671, and R01HG005092 (Green). The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of NIH or the CSER Consortium. Thanks to Heather Bennett, J.D., and Jon Watkins, J.D. candidate, for research assistance during this project and to Audrey Boyle for outstanding management of the work yielding this paper. Thanks also to Sydney Viel, M.P.H., at the University of Minnesota’s Clinical and Translational Research Institute for review of the templates offered in the Appendices.

References

- 1.Wolf SM, et al. Returning a Research Participant’s Genomic Results to Relatives: Analysis and Recommendations. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2015;43(3):440–463. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf SM, Koenig BA, Petersen G, editors. Return of Genomic Research Results to a Participant’s Family, Including After Death. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2015;43(3):437–593. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.See Breitkopf CR, et al. Preferences Regarding Return of Genomic Results to Relatives of Research Participants, Including After Participant Death: Empirical Results from a Cancer Biobank. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2015;43(3):464–475. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12289.Breitkopf CR, et al. Attitudes Toward Return of Genetic Research Results to Relatives, Including after Death: Comparison of Cancer Probands, Blood Relatives, and Spouse/Partners. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. doi: 10.1177/1556264618769165. (in press)

- 4.On the emerging literature concerning return of results to relatives, including when the proband is deceased, see Goodman JL, et al. Discordance in Selected Designee for Return of Genomic Findings in the Event of Participant Death and Estate Executor. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine. 2017;5(2):172–176. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.274.Siminoff LA, et al. Family Decision Maker Perspectives on the Return of Genetic Results in Biobanking Research. Genetics in Medicine. 2016;18(1):82–88. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.38.Amendola LM, et al. Patients’ Choices for Return of Exome Sequencing Results in the Event of their Death. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2015;43(3):476–485. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12290.Wolf, et al. supra note 1; Graves KD, et al. Communication of Genetic Test Results to Family and Health Care Providers Following Disclosure of Research Results. Genetics in Medicine. 2014;16(4):294–301. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.137.Milner LC, Liu EY, Garrison NA. Relationships Matter: Ethical Considerations for Returning Results to Family Members of Deceased Subjects. American Journal of Bioethics. 2013;13(10):66–67. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2013.828533.Taylor HA, Wilfond BS. The Ethics of Contacting Family Members of a Subject in a Genetic Research Study to Return Results for an Autosomal Dominant Syndrome. American Journal of Bioethics. 2013;13(10):64–65. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2013.828523.Chan B, et al. Genomic Inheritances: Disclosing Individual Research Results from Whole-Exome Sequencing to Deceased Participants’ Relatives. American Journal of Bioethics. 2012;12(10):1–8. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2012.699138.Rothstein MA. Disclosing Decedents’ Research Results to Relatives Violates the HIPAA Privacy Rule. American Journal of Bioethics. 2012;12(10):16–17. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2012.699588.Bredenoord AL, van Delden JJM. Disclosing Individual Genetic Research Results to Deceased Participants’ Relatives by Means of a Qualified Disclosure Policy. American Journal of Bioethics. 2012;12(10):12–14. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2012.699145.Tassé AM. The Return of Results of Deceased Research Participants. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2011;39(4):621–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2011.00629.x.Ormondroyd E, et al. Communicating Genetics Research Results to Families: Problems Arising When the Patient Participant Is Deceased. Psycho-Oncology. 2008;17(8):804–811. doi: 10.1002/pon.1356.See also National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), Informed Consent for Genomics Research, Special Considerations for Genome Research, Considerations for Families, at <https://www.genome.gov/27559024/informed-consent-special-considerations-for-genome-research/> (last visited October 21, 2017).

- 5.See National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), Informed Consent for Genomics Research, Special Considerations for Genome Research, Studies Involving Children, at <https://www.genome.gov/27559024/informed-consent-special-considerations-for-genome-research/> (last visited October 21, 2017); Botkin JR, et al. Points to Consider: Ethical, Legal, and Psychosocial Implications of Genetic Testing in Children and Adolescents. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2015;97(1):6–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.05.022.Scollon S, et al. Pediatric Cancer Genetics Research and an Evolving Preventive Ethics Approach for Return of Results after Death of the Subject. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2015;43(3):529–537. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12295.Clayton EW, et al. Addressing the Ethical Challenges in Genetic Testing and Sequencing of Children. American Journal of Bioethics. 2014;14(3):3–9. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2013.879945.Ross LF, et al. Technical Report: Ethical and Policy Issues in Genetic Testing and Screening of Children. Genetics in Medicine. 2013;15(3):234–245. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.176.Green RC, et al. ACMG Recommendations for Reporting of Incidental Findings in Clinical Exome and Genomic Sequencing. Genetics in Medicine. 2013;15(7):565–574. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.73.

- 6.See Weitzel KW, et al. The IGNITE Network: A Model for Genomic Medicine Implementation and Research. BMC Medical Genomics. 2016;9(1) doi: 10.1186/s12920-015-0162-5.Williams MS. Perspectives on What Is Needed to Implement Genomic Medicine. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine. 2015;3(3):155–159. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.135.

- 7.Wolf, et al. supra note 1, at 448 (emphasis omitted).

- 8.As we stated in our prior paper, “In different contexts, the representative may vary. A Legally Authorized Representative (LAR), Executor, Next-of-Kin, Spouse or Partner, or Parent/Guardian may qualify, depending on applicable federal and state law. HIPAA uses the term ‘personal representative’ to refer to the authorized representative, including after the participant’s death” Wolf, et al. supra note 1, at 460. For further discussion, see id., at 441, 443–44, 449, 460, 461 n. 15.

- 9.Id., at 448 (emphasis omitted).

- 10.See note 3, supra.

- 11.Wolf, et al. supra note 1.

- 12.This project participated in the CSER1 Consortium, whose website was at <https://cser-consortium.org/>. This is now the website for the follow-on CSER2 Consortium, but includes CSER1-generated resources. For a description of the work of the CSER1 Consortium, see Green RC, et al. Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research Consortium: Accelerating Evidence-Based Practice of Genomic Medicine. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2016;98(6):1051–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.04.011.For a description of CSER2, see National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), Clinical Sequencing Evidence-Generating Research (CSER2), at <https://www.genome.gov/27546194/clinical-sequencing-exploratory-research-cser/> (last visited October 27, 2017).

- 13.Consent models in the literature include those posted by the eMERGE Network, at <https://emerge.mc.vanderbilt.edu/consentforms/> (last visited November 9, 2017).

- 14.These forms and processes may also need to be customized depending on applicable federal and state law. For example, some institutions in which research is conducted may be covered by HIPAA, while others are not. In addition, state law may address privacy and disclosure, as well as who may serve as the research participant’s Representative to make decisions about sharing their genomic results when the participant has lost decisional capacity or died. See Wolf, et al. supra note 1. The potential legal issues suggest that researchers and their institutions should obtain legal consultation as needed.

- 15.See, e.g., Jarvik GP, et al. Return of Genomic Results to Research Participants: The Floor, the Ceiling, and the Choices in Between. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2014;94(6):818–826. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.04.009.

- 16.Amendola, et al. supra note 4.

- 17.The MRCT Center of Harvard and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, MRCT Return of Results Toolkit, Version 2.0, Oct. 2, 2015, available at <http://mrctcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/2015-10-02-MRCT-ROR-Toolkit-Version-2.0-2.pdf> (last visited October 21, 2017).

- 18.Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, Pub. L. No. 104–191, 110 Stat. 1936 (1996), codified at 42 U.S.C. § 300gg and 29 U.S.C. §§ 1181 et seq. and 42 U.S.C. §§ 1320d et seq. See Wolf, et al. supra note 1, at n. 17 on HIPAA allowing a family member’s physician to obtain an individual’s protected health information when relevant to the family member’s treatment.

- 19.See Wolf, et al. supra note 1.

- 20.See, e.g., Burke W, Evans BJ, Jarvik GP. Return of Results: Ethical and Legal Distinctions between Research and Clinical Care. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 2014;166(1):105–111. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31393.Arango NP, et al. A Feasibility Study of Returning Clinically Actionable Somatic Genomic Alterations Identified in a Research Laboratory. Oncotarget. 2017;8(26):41806–41814. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16018.

- 21.Jarvik, et al. supra note 15.

- 22.See, e.g., National Institutes of Health, Research Involving Individuals with Questionable Capacity to Consent: Points to Consider, at <http://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/questionablecapacity.htm> (last visited October 21, 2017); Grady C. Enduring and Emerging Challenges of Informed Consent. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(9):855–862. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1411250.

- 23.Wolf, et al. supra note 1. See also note 8, supra.

- 24.Id.

- 25.Id., at 451 and n. 69.

- 26.Id., at 450.

- 27.Sabatello M, Appelbaum PS. Raising Genomic Citizens: Adolescents and the Return of Secondary Genomic Findings. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2016;44(2):292–304. doi: 10.1177/1073110516654123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Brothers KB, et al. Practical Guidance on Informed Consent for Pediatric Participants in a Biorepository. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2014;89(11):1471–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Holm IA, et al. Guidelines for Return of Research Results from Pediatric Genomic Studies: Deliberations of the Boston Children’s Hospital Gene Partnership Informed Cohort Oversight Board. Genetics in Medicine. 2014;16(7):547–552. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), Protection of Human Subjects, Requirements for Permission by Parents or Guardians and for Assent by Children, 45 C.F.R. § 46.408 (2017). This paper generally refers to permission from both parents (or a guardian), as DHHS states that, “In general, permission should be obtained from both parents before a child is enrolled in research. However, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) may find that the permission of one parent is sufficient for research to be conducted under [Common Rule sections] 46.404 or 46.405. When research is to be conducted under 46.406 and 46.407 permission must be obtained from both parents, unless one parent is deceased, unknown, incompetent, or not reasonably available, or when only one parent has legal responsibility for the care and custody of the child” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP), Research with Children FAQs, at <https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/guidance/faq/children-research/index.html> (last visited October 25, 2017).

- 29.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), Protection of Human Subjects, Requirements for Permission by Parents or Guardians and for Assent by Children, supra note 28.

- 30.See note 5, supra; Hufnagel SB, et al. Adolescent Preferences Regarding Disclosure of Incidental Findings in Genomic Sequencing that Are Not Medically Actionable in Childhood. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2016;170(8):2083–2088. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37730.Wilfond BS, Fernandez CV, Green RC. Disclosing Secondary Findings from Pediatric Sequencing to Families: Considering the ‘Benefit to Families,’. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2015;43(3):552–558. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12298.

- 31.See note 5, supra.

- 32.Wolf, et al. supra note 1, at 451–52, 456, 459.

- 33.Id., at 456.

- 34.Id., at 456, 459.

- 35.Wolf, et al. supra note 1.

- 36.See note 3, supra.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.