Abstract

Zolpidem is an imidazopyridine nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic drug with a high affinity to the α1 subunit of the gamma amino butyric acid A receptor It is the first pharmacological option in the short-term management of sleep-onset insomnia. Initially considered a safer drug compared to benzodiazepines because of lower liability for abuse and dependence, recently, an increasing body of reports has questioned zolpidem's proneness to misuse. In this report, we describe a case of serious zolpidem abuse requiring pharmacological washout during hospitalization because of previous withdrawal seizures in a patient with chronic sleep-onset and maintenance insomnia.

Citation:

Chiaro G, Castelnovo A, Bianco G, Maffei P, Manconi M. Severe chronic abuse of zolpidem in refractory insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(7):1257–1259.

Keywords: zolpidem, abuse, insomnia, power spectrum, electroencephalography, actigraphy, video polysomnography

INTRODUCTION

Zolpidem is an imidazopyridine nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic drug with a high affinity to the α1 subunit of the gamma amino butyric acid A receptor. Zolpidem represents a first-line medication in sleep-onset insomnia.1 Zolpidem is metabolized via CYP3A4, and its pharmacodynamics are influenced by sex and other individual factors. A large survey of about 32,300 adults found that 3% of them had been prescribed zolpidem for insomnia in the preceding month.2 The same survey reported that there had been 53.4 million prescriptions for zolpidem in the United States in 2010.

Initially considered a safer drug compared to benzodiazepines (BZD) because of lower liability for abuse and dependence and a shorter half-life, recently, an increasing body of reports has questioned zolpidem's proneness to misuse, mostly at supratherapeutic doses, ranging from 60 to 2,000 mg daily.3,4 To the best of our knowledge, 61 cases of zolpidem misuse have been reported in the literature so far.5–22 In most of the these cases, a history of alcohol or drug abuse was already present. Studies in healthy volunteers with no history of drug abuse suggest that zolpidem has only a modest abuse potential.23 Previous reports show that rapid or self-performed washouts from doses of zolpidem higher than 160 mg/d might cause severe withdrawal symptoms, epileptic seizures and psychosis.12,20,24

REPORT OF CASE

A 70-year-old woman, known for tension-type headache and a 35-year long history of primary insomnia, was referred to our sleep center to manage a strong abuse of hypnotics. During the past years, she was treated uninterruptedly with different medications. Initially, the patient was started on methaqualone (toquilone compositum), which she took at increasing dosages of up to 5 g/d for over 10 years. She had already undergone three epileptic seizures during periods of relative abstinence from the drug. A first hospitalization to discontinue methaqualone in favor of valproate failed. Another ineffective washout attempt was performed during a second hospitalization, in which the patient developed an abstinence syndrome, controlled with a combination of clomethiazol and valproate. Once discharged, she started taking methaqualone again.

Once methaqualone was withdrawn from the market (2005), the patient was switched to mirtazapine (30 mg/d) and oxazepam (increased up to 115 mg/d). Since none of these drugs had proved beneficial for insomnia, zolpidem was started, which the patient gradually and autonomously increased up to 1,200 mg/d (120 tablets, equivalent to 4 boxes per day). The patient used different illicit strategies to gather such a high amount of medication. Because of serious financial problems due to the costs of such therapy, the patient's husband convinced her to be admitted to our sleep center in order to attempt another pharmacological washout.

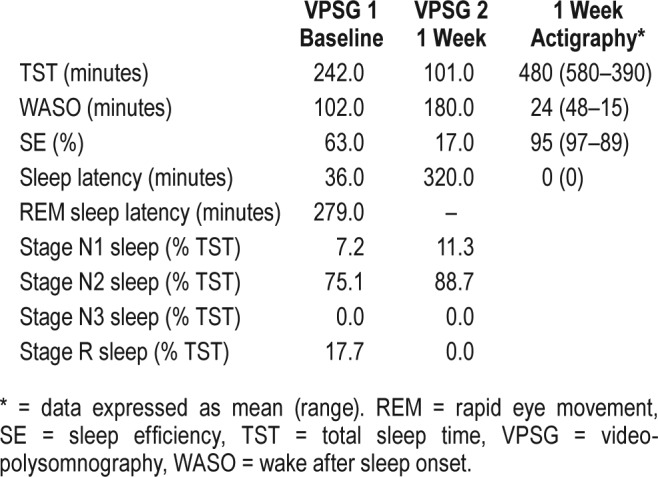

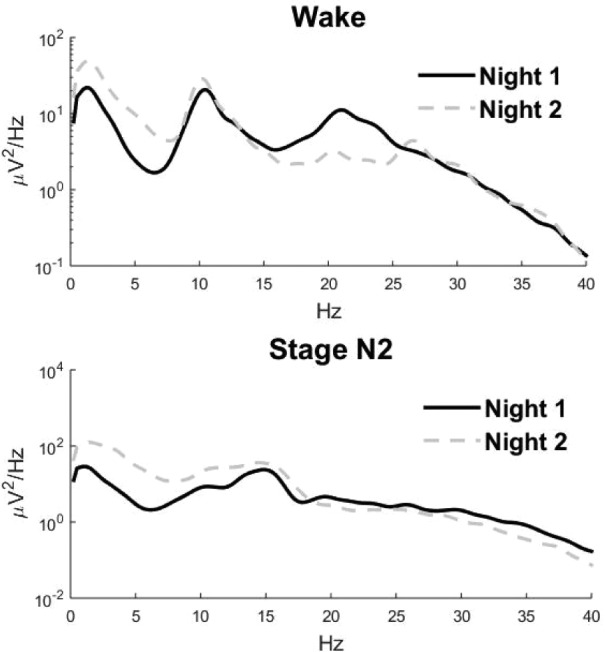

On her first clinical examination, the patient claimed that she took about an hour to fall asleep and that she could only sleep for one hour continuously, despite treatment. Her general and neurological status were normal, in particular, she did not suffer from respiratory depression, nor was she delirious. During hospitalization, she was given the diagnosis of enduring personality change after a catastrophic experience (ICD-10 F62.0), namely posttraumatic stress disorder. A first video polysomnography (VPSG) was performed in the semi-intensive care unit (Stroke Unit) of our neurology ward. The patient took zolpidem 1,200 mg/d, as she would do at home. Medical surveillance was available constantly. The examination confirmed a striking fragmentation of the sleep structure, a severe reduction of sleep duration, sleep efficiency and slow wave sleep and an increased REM sleep latency (Table 1). No breathing or motor abnormalities during sleep were detected. A complete washout was performed in 10 days. Zolpidem was gradually replaced by sertraline 75 mg/d, clonazepam 2 mg/d and pregabalin 150 mg/d. A second VPSG, performed 7 days after the first, still showed severe insomnia. Spectral analysis for both nights was performed on 2-minute segments of stable (arousal- and artifact-free) stage N2 sleep using 2-second epochs for each of the 6 electroencephalography (EEG) channels available (F1, F2, C3, C4, O1, O2 - mastoid referenced).25 Visual comparison of the two spectrograms showed a decrease in beta activity and an increase in slow wave activity (SWA) in the second recording (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Polysomnography and actigraphy parameters.

Figure 1. Spectral analysis.

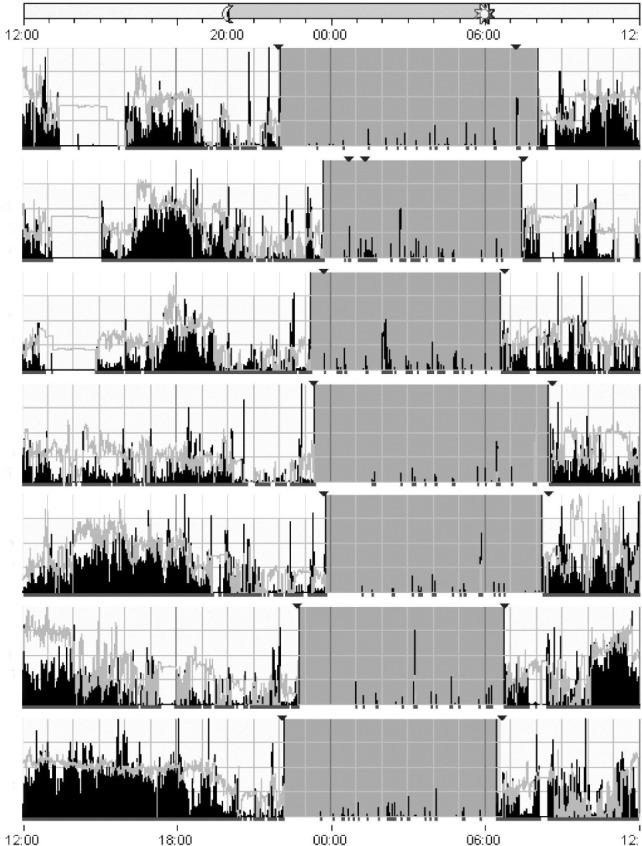

Two months after her discharge, the patient was examined because of severe persistent diarrhea. Sertraline was then reduced to 50 mg/d with remission of the symptom. A 1-week actigraphy recording showed a normalization of the sleep-wake cycle and a strong improvement of insomnia (Figure 2 and Tabe 1). Psychotherapy was started and, at a 1-year follow-up visit, the patient reported of having spontaneously discontinued all medications. However, a urine toxicology screening test proved positive for benzodiazepine metabolites.

Figure 2. Data from 1 week of actigraphy.

One year later she was again admitted to the hospital for unrelated medical reasons. On that occasion, the patient underwent another epileptic seizure because of relative abstinence from clomethiazol and alprazolam. These were strongly reduced and the patient was started on antiepileptic therapy with levetiracetam and pregabalin. She was discharged to a nursing home.

DISCUSSION

We described a case of very serious zolpidem abuse requiring pharmacological washout during hospitalization in a patient with primary insomnia and a history of previous drug misuse and withdrawal seizures. Despite the very high doses of zolpidem, two serial VPSG recordings showed severe insomnia, which recovered only later, as demonstrated in the actigraphy recording. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of zolpidem abuse and its discontinuation documented through VPSG and actigraphy studies, including EEG spectral analysis, which showed a decrease in beta activity, together with an increase in SWA one week after zolpidem dismissal was started, in line with previous findings.26,27

The case reported emphasizes important issues that should be taken into account when prescribing zolpidem for chronic insomnia. (1) Although less frequent in comparison to BZD misuse, dependence and severe abuse can occur also with zolpidem, which was previously considered relatively safe.4 (2) Regardless of dosage, in the long term, zolpidem might be ineffective in treating insomnia. Inefficacy was indeed present in our patient. Interestingly, there were also no sedation, psychostimulant effects, respiratory depression, delirium or hypnosedative-induced complex behaviors, which have been reported in other patients. One possible explanation thereof could be that zolpidem is particularly associated with long-term tolerance, and that tolerance per se, as well as efficacy, might depend on individual features like sex.28,29 (3) In uncertain cases in which a differential diagnosis between paradoxical or drug-induced insomnia exists, an actigraphy or VPSG study might be useful in differentiating the two entities and in following up their evolution. (4) Rapid withdrawal of high doses of zolpidem should be performed in a hospital setting and a cross-titration with a long-acting BZD as clonazepam is preferable, as it might limit, or even avoid, adverse events, especially in patients with a previous history of withdrawal seizures. (5) Lastly, in patients with known drug misuse, zolpidem should be avoided or discontinued in favor of medications with lower risk for dependence and/or abuse such as antidepressants. Even better, a structured program of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia should be encouraged.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have seen and approved the manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wisden W, Yu X, Franks NP. GABA receptors and the pharmacology of sleep. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2017 doi: 10.1007/164_2017_56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertisch SM, Herzig SJ, Winkelman JW, Buettner C. National use of prescription medications for insomnia: NHANES 1999-2010. Sleep. 2014;37:343–349. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Victorri-Vigneau C, Gerardin M, Rousselet M, Guerlais M, Grall-Bronnec M, Jolliet P. An update on zolpidem abuse and dependence. J Addict Dis. 2014;33:15–23. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2014.882725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacFarlane J, Morin CM, Montplaisir J. Hypnotics in insomnia: the experience of zolpidem. Clin Ther. 2014;36:1676–1701. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chattopadhyay AC, Shukla L, Kandasamy A, Benegal V. High-dose zolpidem dependence - psychostimulant effects? A case report and literature review. Ind Psychiatry J. 2016;25:222–224. doi: 10.4103/ipj.ipj_80_14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haji Seyed Javadi SA, Hajiali F, Nassiri-Asl M. Zolpidem dependency and withdrawal seizure: a case report study. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16:e19926. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.19926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eslami-Shahrbabaki M, Barfeh B, Nasirian M. Persistent psychosis after abuse of high dose of zolpidem. Addict Health. 2014;6:159–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu WY, Chiu NY. Intravenous zolpidem injection in a zolpidem abuser. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2013;46:121–122. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1327609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heydari M, Isfeedvajani MS. Zolpidem dependence, abuse and withdrawal: a case report. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18:1006–1007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quaglio G, Faccini M, Vigneau CV, et al. Megadose bromazepam and zolpidem dependence: two case reports of treatment with flumazenil and valproate. Subst Abus. 2012;33:195–198. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2011.638735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen SC, Chen HC, Liao SC, Tseng MC, Lee MB. Detoxification of high-dose zolpidem using cross-titration with an adequate equivalent dose of diazepam. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34:210e5–210e7. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang LJ, Ree SC, Chu CL, Juang YY. Zolpidem dependence and withdrawal seizure--report of two cases. Psychiatr Danub. 2011;23:76–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oulis P, Nakkas G, Masdrakis VG. Pregabalin in zolpidem dependence and withdrawal. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011;34:90–91. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e31820a3b5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damm J, Eser D, Moeller HJ, Rupprecht R. Severe dependency on zolpidem in a patient with multiple sclerosis suffering from paraspasticity. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11:516–518. doi: 10.3109/15622970903369973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aggarwal A, Sharma DD. Zolpidem withdrawal delirium: a case report. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;22(4):451o.e27–451.e28. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2010.22.4.451.e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Svitek J, Heberlein A, Bleich S, Wiltfang J, Kornhuber J, Hillemacher T. Extensive craving in high dose zolpidem dependency. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32:591–592. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jana AK, Arora M, Khess CR, Praharaj SK. A case of zolpidem dependence successfully detoxified with clonazepam. Am J Addict. 2008;17:343–344. doi: 10.1080/10550490802139168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharan P, Bharadwaj R, Grover S, Padhy SK, Kumar V, Singh J. Dependence syndrome and intoxication delirium associated with zolpidem. Natl Med J India. 2007;20:180–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mariani JJ, Levin FR. Quetiapine treatment of zolpidem dependence. Am J Addict. 2007;16:426. doi: 10.1080/10550490701525467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liappas IA, Malitas PN, Dimopoulos NP, et al. Zolpidem dependence case series: possible neurobiological mechanisms and clinical management. J Psychopharmacol. 2003;17:131–135. doi: 10.1177/0269881103017001723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hajak G, Muller WE, Wittchen HU, Pittrow D, Kirch W. Abuse and dependence potential for the non-benzodiazepine hypnotics zolpidem and zopiclone: a review of case reports and epidemiological data. Addiction. 2003;98:1371–1378. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaffe JH, Bloor R, Crome I, et al. A postmarketing study of relative abuse liability of hypnotic sedative drugs. Addiction. 2004;99:165–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkinson CJ. The abuse potential of zolpidem administered alone and with alcohol. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;60:193–202. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00584-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang MC, Lin HY, Chen CH. Dependence on zolpidem. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61:207–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welch P. The use of fast Fourier transform for the estimation of power spectra: A method based on time averaging over short, modified periodograms. IEEE Transactions on Audio and Electroacoustics. 1967;15:70–73. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunner DP, Dijk DJ, Munch M, Borbely AA. Effect of zolpidem on sleep and sleep EEG spectra in healthy young men. Psychopharmacology. 1991;104:1–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02244546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feige B, Voderholzer U, Riemann D, Hohagen F, Berger M. Independent sleep EEG slow-wave and spindle band dynamics associated with 4 weeks of continuous application of short-half-life hypnotics in healthy subjects. Clin Neurophysiol. 1999;110:1965–1974. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(99)00147-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cubala WJ, Landowski J, Wichowicz HM. Zolpidem abuse, dependence and withdrawal syndrome: sex as susceptibility factor for adverse effects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:444–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.03028.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cubala WJ, Wichowicz HM. Dependence on zolpidem: is pharmacokinetics important? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62:127. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]