Abstract

Objective

Insomnia is prevalent in knee osteoarthritis (KOA). Research indicates that sleep disruption may amplify clinical pain by altering central pain modulation, suggesting that treating insomnia may improve pain. We sought to: 1) evaluate the efficacy of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) in KOA, 2) determine whether improvements in sleep predict reduced pain, and 3) determine whether alterations in pain modulation mediate improvements in clinical pain.

Methods

We conducted a double-blinded, randomized, active placebo-controlled clinical trial of CBT-I in 100 KOA patients with insomnia [Mean Age = 59.5(9.5)]. Patients were randomized to 8-sessions of CBT-I or Behavioral Desensitization-Placebo. We conducted in-home polysomnograms, diary assessment, and sensory tests of pain modulation at baseline, posttreatment, 3-and 6-months.

Results

Intent-to-treat analyses demonstrated that both groups yielded substantial improvements in sleep. CBT-I demonstrated significantly greater reductions in wake after sleep onset time (WASO), measured via diary and actigraphy [PSG trended, (p=.075)]. Both groups reported significant and comparable reductions in pain over 6 months with a third demonstrating ≥ 30% reduction in pain severity. Baseline-to-posttreatment reductions in Diary and PSG WASO predicted subsequent decreases in clinical pain. This effect was significantly greater for CBT-I compared to BD. We found no significant changes in laboratory measures of pain modulation.

Conclusion

Compared to active placebo, CBT-I was efficacious in reducing sleep maintenance insomnia. Treatment decreased clinical pain, but not pain modulation, suggesting that CBT-I has potential to augment pain management in KOA. Future work is needed to identify the mechanisms by which improved sleep reduces clinical pain.

Keywords: Insomnia, osteoarthritis, cognitive-behavior therapy, chronic pain, pain modulation, conditioned pain modulation, temporal summation, sleep disorders, polysomnography

Over 21 million adults in the US suffer from osteoarthritis (OA)(1). OA is characterized by articular cartilage loss, synovitis, and joint capsule thickening(2). Knee OA (KOA), the most common form of OA, incurs tremendous healthcare costs(3) and is a major cause of disability(4) and impaired quality of life, world-wide(5). Aside from knee pain, insomnia is one of the most common and disabling symptoms associated with OA. As many as 81% of patients report trouble maintaining sleep, the most frequent insomnia complaint in OA(6). Greater pain and decreased physical function have both been linked with KOA-related insomnia(7). The mechanisms of and relationships between pain and insomnia in KOA, however, are poorly understood. Radiographic markers of disease severity are relatively weak correlates of pain(2) and many patients with minimal nighttime pain continue to report poor sleep(8). Central pain modulatory processes are increasingly recognized as playing a role in OA pain(9) and are a possible underlying mechanism linking insomnia and pain. Several studies have found laboratory measures of diminished pain inhibitory capacity and heightened central pain facilitation to be associated with clinical pain severity(10;11). Experiments have also demonstrated that sleep disruption may impair these same pain modulatory processes, suggesting that sleep disruption, may directly amplify OA pain(12;13). The possibility that treating insomnia may improve the function of these centrally regulated features of OA pain has yet to be evaluated, however.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), a short-term psychological intervention with well-established efficacy in primary insomnia(14) is a promising treatment approach to evaluate whether improving sleep maintenance, improves OA pain. Several small studies of CBT-I in chronic pain disorders, including one in OA(15) have demonstrated that CBT-I improves sleep maintenance insomnia(16-20). The effect of CBT-I on clinical pain, in these studies, however, has been mixed, due in part, to statistical power limitations(21). Moreover, none of these studies utilized double-blinded, placebo-controlled methodology.

A recent multisite clinical trial, “Lifestyles,” combined CBT for pain with CBT-I (CBT-IP) in KOA(22) and found that CBT-IP improved insomnia severity, compared to education control, but failed to improve clinical pain. Secondary analyses, however, found that CBT-IP decreased long-term pain in a subgroup of patients with severe baseline pain and insomnia(23) and that individuals reporting clinically significant improvements in insomnia at posttreatment demonstrated significant long-term pain reductions(24). The results of this study are promising, but the lack of active placebo control leaves open the question of whether improvements in sleep and pain result from specific or non-specific components of the intervention.

We sought to: 1) conduct a double-blinded randomized placebo controlled trial of CBT-I in KOA to evaluate the efficacy of CBT-I, in a polysomnographically-screened sample of KOA patients, 2) determine whether improvements in sleep are associated with improvements in clinical pain, and 3) determine whether alterations in laboratory measures of pain modulation mediate sleep-related improvements in clinical pain.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We conducted this study at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, MD, USA. All patients were enrolled between 09/2008 and 04/2013. Treatments and follow up were completed by 01/2014.

Inclusion Criteria

Patients meeting criteria for KOA(25), as determined by a rheumatologist (UH), were eligible. Additional KOA criteria included: 1) radiographic evidence of KOA with a Kellgren-Lawrence grade ≥ 1; 2) typical knee pain ratings, ≥ 2 out of 10, experienced >5 days / week for > 6 months; 3) patients taking NSAIDs were required to be on a stable dose. We also required patients to meet criteria for Insomnia Disorder(26). Additional insomnia criteria included: 1) symptom duration > 1 month; 2) > 2 nocturnal awakenings of >15 minutes duration or self-reported wake after sleep onset time and / or latency to sleep onset >30 minutes.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were: 1) moderate-severe sleep apnea (apnea/hypopnea index ≥15); 2) moderate to severe periodic limb movement disorder (periodic limb movement with arousals index ≥15; 3) sleep or pain disorders other than insomnia or OA; 4) unstable major medical diseases; 5) cognitive impairment [Mini Mental State Exam score < 24]; 6) Unstable major psychiatric disorder or history of psychotic disorders; 7) Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Scale score ≥ 27 or suicidal ideation; 8) regular (≥ 3/week) use of narcotics (opioids) or sedative hypnotics within the past one month; 9) unable to discontinue use of narcotics or sedatives 1-week prior to study; 10) unable to discontinue all analgesic usage within 24 hours of pain testing; 12) regular nicotine use; 13) heavy caffeine use [(>3 cups of coffee/day];14) pregnant; 15) positive urine test for recreational drugs of abuse, sedative hypnotics, and opioids.

Study Procedures

Screening

The Johns Hopkins IRB Board approved the study protocol. All participants completed written informed consent. Participants completed two screening visits to establish eligibility. Visit 1 included: urine toxicology; bilateral, knee radiographs (standing, flexed), completion of screening questionnaires(27-30) and research diagnostic interviews(31;32). During the second screening visit, we administered outcome questionnaires, conducted quantitative sensory testing (QST) and a polysomnogram (PSG).

In-Home, Nocturnal Polysomnogram

We conducted a full diagnostic PSG, according to standardized published research procedures developed for unattended, in home ambulatory recordings(33). See supplemental methods.

Outcome Measures

We collected all primary and secondary outcome measures, and QST indices of pain modulation at Baseline, Midtreatment (except PSG), Posttreatment, Three and Six month follow up periods.

Primary Sleep-Related Outcomes

Wake After Sleep Onset (WASO)

We selected Diary, PSG, and Actigraphy measures of WASO as a priori primary outcomes, because middle of the night awakening is the most common insomnia complaint associated with KOA(6). Patients completed electronic personal digital assistants (PDAs) with date and time stamped entries upon waking each morning for two weeks. We averaged across days to quantify Diary WASO(34). We quantified PSG WASO for one night at each assessment period. To quantify WASO via actigraphy, subjects wore a MiniMitter Actiwatch2 triaxial accelerometer continuously on the non-dominant wrist for two weeks(35). We averaged across days. See supplemental methods.

Secondary Sleep-Related Outcomes

Diary, PSG, and Actigraphy Measures of Sleep Continuity

We calculated standard sleep continuity parameters including: latency to initial sleep onset (SL); 2) total sleep time (TST); and 3) sleep efficiency % [SE% (total sleep time/time in bed × 100)].

Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)

We used the Total Score from the ISI, a 7-item questionnaire assessing assess insomnia severity(36).

Primary Clinical Pain-Related Outcomes

Diary Pain Intensity Index (PII-D)

Patients completed pain ratings of “usual pain.” experienced during the entire day on a PDA via sliding Visual Analogue Scale [(VAS) “0” equal to “no pain” and “100” equal to “the worst pain imaginable”](37). Patients made ratings each night, before retiring to bed and scores were averaged over the two-week period.

Secondary Clinical Pain-Related Outcomes

Western Ontario McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Scale (WOMAC, 3.1)(38)

The WOMAC is a validated KOA specific outcomes questionnaire, which yields three scales: 1) pain severity, 2) disability and 3) joint stiffness and a total score. Ratings are made on a 10 cm VAS.

Quantitative Sensory Tests (QST) of Pain Modulation

Conditioned Pain Modulation (CPM)

CPM provides a measure of endogenous pain inhibitory capacity(12). In the current study it refers to the ability of a noxious conditioning stimulus (cold water hand submersion) to inhibit the pain of a second testing stimulus [pressure pain threshold (PPTh) measured on the trapezius]. Details are published elsewhere(39) and described in the supplemental methods. We conducted 4 CPM trials and calculated a CPM index as mean PPTh during cold pressor / mean PPTh prior to cold pressor.

Temporal Summation (TS)

TS refers to the CNS enhancement of pain caused by repeated noxious stimulation(40). We obtained pain ratings in response to a single punctate noxious stimulus and in response to a sequence of 10 identical punctate noxious stimuli as previously described and detailed in the Supplemental Methods(11). We conducted 4 TS trials by administering two different weighted probes (256 mN and 512 mN) at two anatomic locations (the third digit of the middle phalange and medial patella of the index knee. We calculated wind-up ratios as the mean pain rating of trains divided by the pain rating of the single stimuli. This ratio was then converted to a Z – score for each site and weight. Z-scores were then averaged within-subject to yield one global TS index for each assessment time point.

Randomization

We randomly assigned patients with equal allocation to CBT-I or Placebo, Behavioral Desensitization (BD).

Blinding

We informed patients that they had a 50% chance of being assigned to placebo. They were not told about the nature of the placebo. We instructed patients to refrain from discussing knowledge of a placebo condition with their interventionist. Assessors, Interventionists, and PSG scorers were blind to assignment and hypotheses. Interventionists were told that the purpose of the study was to test two different psychological interventions for insomnia in KOA, i.e., CBT-I, a treatment developed for patients with primary insomnia and 2) Behavioral Desensitization, a promising experimental intervention for insomnia.

Interventionists

With the exception of two advanced psychology doctoral candidates (1 female), all interventionists were postdoctoral clinical psychology fellows [(n=5, 3 females)] or faculty (n=2). with experience in behavioral medicine All but two interventionists delivered both treatments.

Treatment Protocols

CBT- I

We administered a standardized, 8-session (45 mins. / session) multi-component intervention, based on our published treatment manual(41). Major intervention components included: sleep restriction therapy, stimulus control therapy, cognitive therapy for insomnia, and sleep hygiene education.

BD(42)

This intervention has been used successfully as a credible placebo in a clinical trial of primary insomnia(43). We adapted the manual used in the prior trial to match our CBT-I protocol for session number and duration. This sham procedure resembles a legitimate desensitization intervention, conferring face validity. See supplemental methods.

Treatment Integrity

The first author supervised interventionists weekly to promote protocol fidelity. Interventionists also completed a structured checklist of session elements. We audiotaped all sessions and randomly selected 15% of records from each interventionist and rated them for the presence or absence of session specific intervention elements. Independent auditors also rated sessions for contamination.

Treatment Credibility and Adherence

At the end of the first and last treatment session, we administered the Therapy Evaluation Questionnaire (TEQ), a widely-used, 8-item measure of perceived credibility, outcome expectancy, and therapist competence(44). Subjects made ratings on a 0 to 10 scale with zero reflecting a negative impression and 10 reflecting an extremely positive impression.

To assess adherence, we administrated a questionnaire before each treatment session asking patients to rate on a likert scale (0 = not at all – zero days to 7 = followed precisely every day), how closely and frequently they followed their interventionist’s various prescriptions in the preceding week. We informed patients that interventionists were blind to TEQ and adherence questionnaire responses.

Statistical Analysis

We first inspected the data for visual trends to determine the optimal modeling approach. We performed intent-to-treat analyses, using mixed-effects models to account for random variation in intercepts, control for autoregression, and include all available data points(45). All models that included sleep variables excluded the mid-treatment assessment point, because PSG was not conducted at mid treatment. In all models, the primary predictor was a dichotomous treatment group variable (CBT-I vs. BD). All models included the same set of subject-level covariates, chosen a priori: age, sex, race, BMI, education level, KL knee grade, and the baseline value for the outcome. See supplemental methods.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Table 1 presents baseline demographic and clinical characteristic by group for the 100 randomized patients.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics by Treatment Group

| CBT-I (N=50) | BD (N=50) | All Patients N=100 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 59.2 (9.9) | 59.6 (9.1) | 59.4 (9.5) |

| Female, % (no.) | 76.0 (38) | 82.0 (41) | 79.0 (79) |

| Race/Ethnicity, % (no.) | |||

| African American, | 42.0 (21) | 44.0 (22) | 43.0 (43) |

| Caucasian | 56.0 (28) | 54.0 (27) | 55.0 (55) |

| Asian | 0.0 (0) | 2.0 (1) | 1.0 (1) |

| Multiracial | 2.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 1.0 (1) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) |

| Education Level, % (no.) | |||

| High School/Some College | 62.0 (31) | 34.0 (17) | 48.0 (48) |

| College Graduate | 16.0 (8) | 34.0 (17) | 25.0 (25) |

| Graduate Studies | 22.0 (11) | 32.0 (16) | 27.0 (27) |

| Yearly Household Income, % (no.) | |||

| $25,000 or less | 28.0 (14) | 18.0 (9) | 23.0 (23) |

| $25,001-$50,000 | 26.0 (13) | 30.0 (15) | 28.0 (28) |

| $50,001-$75,000 | 8.0 (4) | 14.0 (7) | 11.0 (11) |

| >$75,000 | 24.0 (12) | 22.0 (11) | 23.0 (23) |

| Medications, % (no) | |||

| NSAIDs | 66.0 (33) | 72.0 (36) | 69.0 (69) |

| Anti-Hypertensives | 40.0 (20) | 36.0 (18) | 38.0 (38) |

| Statins | 16.0 (8) | 30.0 (15) | 23.0 (23) |

| Anti-Depressants | 12.0 (6) | 18.0 (9) | 15.0 (15) |

| Opioids | 12.0 (6) | 8.0 (4) | 10.0 (10) |

| Anti-Diabetics | 8.0 (4) | 6.0 (3) | 7.0 (7) |

| Anxiolytics | 2.0 (1) | 8.0 (4) | 5.0 (5) |

| Anti-Convulsants | 2.0 (1) | 2.0 (1) | 2.0 (2) |

| Clinical Variables (M, SD) | |||

| Kellgren Lawrence Grade (Index) | 2.3 (1.1) | 2.4 (1.2) | 2.3 (1.2) |

| WOMAC (total score) | 4.9 (2.0) | 5.2 (2.2) | 5.0 (2.1) |

| Knee Pain Duration (years) | 7.1 (9.2) | 7.5 (8.1) | 7.3 (8.6) |

| BMI | 31.6 (6.2) | 31.5 (7.0) | 31.5 (6.6) |

| CESD | 14.6 (7.7) | 14.0 (9.4) | 14.3 (8.6) |

| SBP | 130.1 (21.8) | 129.5 (17.0) | 129.8 (19.4) |

| ISI | 16.8 (5.0) | 17.2 (5.1) | 17.0 (5.0) |

| AHI | 5.4 (4.7) | 5.1 (4.4) | 5.3 (4.6) |

| PLMI_A | 2.6 (6.8) | 2.2 (5.2) | 2.4 (5.9) |

Note. CBT-I = Cognitive behavioral Therapy for Insomnia, BD = Behavioral Desensitization; BMI = body mass index [weight (kg)/ height (m2)]; SBP = systolic blood pressure; ISI= Insomnia Severity Index Total Score; AHI = Apnea / Hyponea Index (apneas+hyponeas/total sleep time); PLMI_A = Periodic Limb Movement Index with arousals (periodic limb movements with arousals/total sleep time)

Attrition

Figure 1 presents attrition and missing visit data. Our overall rate of attrition after randomization was 27% and there was no significant differential drop out by group (30% CBT-I vs. 24% BD, chi square = 8.30, p = .31). Eighty-six percent of patients randomized to CBT-I and 96% randomized to BP completed at least 6 out of 8 treatment sessions (p =.08).

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram.

Treatment Integrity

The mean percentage of treatment elements rated as present in the randomly selected sample of session recordings was 91% for BD and 97% for CBT-I (p=.118). Furthermore, none of the sessions were rated as contaminated by elements from the other treatment.

Treatment Credibility and Adherence

At the beginning of treatment, we found no between group differences on the TEQ in how “understanding” the patients perceived their interventionist to be [(CBT-I M= 9.36(1.31); BD M=8.94(1.33), p=.12] or how successful patients believed their treatment assignment would be in improving arthritis pain be [(CBT-I M= 5.66(2.48); BD M=4.98(2.72), p=.20]. Compared to BD, however, patients randomized to CBT-I, believed CBT-I to be more logical [M=8.94 (1.4) vs. M=6.73(2.45)], more likely to successfully improve sleep [7.92(1.59) vs. M=6.59 (2.39)], and quality of life [8.06 (1.63) vs. 6.76 (2.38)]. They also perceived the CBT-I interventionists as slightly more competent [(M = 9.22(1.30) vs. M = 8.6 (1.37), and would be more confident in recommending CBT-I to a friend with insomnia [8.26 (1.83) vs. M=7.00(2.59)]; all ps<.05). At the end of treatment, we found a similar pattern of significance.

We found no between group differences on self-reported adherence to the interventionist’s behavioral prescriptions at any treatment session. Overall Mean adherence ratings were: 5.49(.93), and 5.50(1.29) for CBT-I and BD, respectively (p =.97).

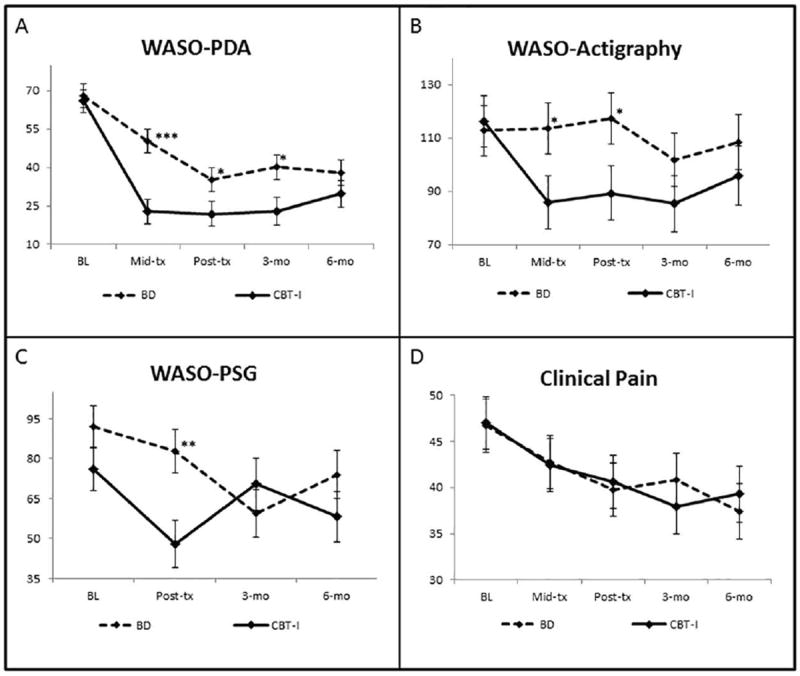

Primary Sleep Outcomes

Figure 2 shows mean WASO over time by group. Because the majority of change in WASO was observed between the baseline and post-treatment periods, with little change during the post-treatment periods, we focused our analyses on group differences averaged across post-treatment and follow-up time points, controlling for baseline values and covariates. Table 2 presents the results of the mixed effects models evaluating the effect of treatment on WASO. We found significant group differences on Diary WASO across the post-treatment, 3, and 6-month follow up time points (p < .001). Specifically, the CBT group reported an average of approximately 12 fewer minutes of WASO across all post-treatment and follow up assessment periods than the BD group. A similar effect was observed for Actigraphy WASO (p < .05), with approximately 14 fewer minutes of WASO for CBT-I group compared BD. The group effect for PSG WASO trended in the same direction, with the CBT group evidencing approximately10 fewer minutes WASO than the BD group (p = .08). Table 3 presents means and effect sizes for primary and secondary sleep-related outcomes.

Figure 2.

Trajectories of Primary Sleep and Clinical Pain Outcomes by Group (Means and SEs, unadjusted for covariates).

Note: WASO = Wake After Sleep Onset Time (minutes.); Clinical Pain = Diary Pain Intensity Index (0 = “no pain” – 100 = “worst pain imaginable”); * = p<.05, **=p<.01; ***=p<.001

Table 2.

Mixed Effects Models for Primary Sleep and Pain-Related Outcomes

| Sleep Ω | |||

| WASO Diary (PDA) | β | SE | P |

| Group | -12.328 | 3.308486 | <0.001 |

| WASO PSG | β | SE | P |

| Group | -10.025 | 5.695 | 0.078 |

| WASO Actigraphy | β | SE | P |

| Group | -14.270 | 4.743 | 0.003 |

| Clinical Pain | |||

| PDA Pain Diary (PII-D) | β | SE | P |

| Group | -3.435 | 3.560 | 0.336 |

| Time (days) | -0.035 | 0.007 | <0.001 |

| Group * Time | 0.014 | 0.009 | 0.123 |

| Quantitative Sensory Testing | |||

| Conditioned Pain Modulation | β | SE | P |

| Group | -0.010 | 0.036 | 0.772 |

| Time (days) | -0.0003 | 0.0002 | 0.051 |

| Group * Time | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.368 |

| Temporal Summation. | β | SE | P |

| Group | 0.036 | 0.123 | 0.771 |

| Time (days) | 0.00001 | 0.0005 | 0.985 |

| Group * Time | -0.001 | 0.001 | 0.413 |

All models adjusted for covariates: age, sex, race, BMI, Education, and Kellgren Lawrence Knee Grade;

Sleep-related models adjusted for baseline outcome (pre-post change). Note: Because the majority of change in WASO was observed between the baseline and post-treatment periods, with little change during the post-treatment periods, group differences for WASO were modeled by averaged across post-treatment and follow-up time points, controlling for baseline values and covariates. CPM = Conditioned Pain Modulation (CPM index = mean pressure pain threshold at the trapezius (PPTh) during cold pressor / mean PPTh trapezius prior to cold pressor, over 4 trials). Values > 1 represent increased pain inhibition, i.e. decreased pain sensitivity. TS = temporal summation of mechanical pain. Values are averaged Z-scores of the wind-up ratios derived from 4 trials by administering two different weighted probes (256 mN and 512 mN) at two anatomic locations (the third digit of the middle phalange and medial patella of the index knee). Higher values indicate increased TS and heightened pain sensitivity.

Table 3.

Means and Effects Sizes for Primary and Secondary Sleep Outcomes

| Measure | Mean (SD) | Effect Size (d) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WASO* | CBT-I | BD | CBT-I | BD | Between Grp. |

| Diary | |||||

| Baseline | 65.96 (37.84) N = 50 | 68.63 (43.12) N = 48 | |||

| Posttreatment | 22.64 (23.53) N = 42 | 35.81 (27.38) N = 48 | -1.095 | -0.810 | -0.285 |

| 3-mo follow-up | 22.57 (20.03) N = 32 | 41.25 (31.69) N = 42 | -1.068 | -0.689 | -0.378 |

| 6-mo follow-up | 31.54 (27.46) N = 32 | 37.48 (30.81) N = 38 | -0.900 | -0.745 | -0.155 |

| Actigraphy | |||||

| Baseline | 117.65 (82.64) N = 47 | 112.72 (66.98) N = 49 | |||

| Posttreatment | 90.33 (58.28) N = 38 | 115.87 (69.68) N = 44 | -0.360 | 0.061 | -0.421 |

| 3-mo follow-up | 87.98 (50.76) N = 33 | 105.01 (68.44) N =39 | -0.413 | -0.146 | -0.266 |

| 6-mo follow-up | 101.83 (72.80) N = 26 | 106.07 (61.49) N = 34 | -0.274 | -0.060 | -0.214 |

| PSG | |||||

| Baseline | 75.83 (47.08) N = 50 | 91. 90 (70.10) N = 50 | |||

| Posttreatment | 46.08 (33.41) N = 38 | 83.25 (70.95) N = 46 | -0.467 | -0.157 | -0.31 |

| 3-mo follow-up | 70.45 (60.21) N = 31 | 62.25 (46.74) N = 38 | -0.093 | -0.543 | 0.449 |

| 6-mo follow-up | 58.01 (46.84) N = 32 | 74.22 (55.43) N = 36 | -0.296 | -0.301 | 0.005 |

| TST | CBT-I | BD | CBT-I | BD | Between Grp. |

| Diary | |||||

| Baseline | 319.63 (70.80) N = 50 | 331.15 (79.70) N = 48 | |||

| Posttreatment | 363.33 (79.37) N = 42 | 404.41 (76.69) N = 48 | 0.528 | 1.014 | -0.486 |

| 3-mo follow-up | 385.93 (57.93) N = 32 | 386.04 (72.00) N = 42 | 0.771 | 0.761 | 0.011 |

| 6-mo follow-up | 382.94 (65.84) N = 32 | 388.89 (62.43) N = 38 | 0.814 | 0.780 | 0.034 |

| Actigraphy | |||||

| Baseline | 298.48 (74.49) N = 47 | 318.88 (86.16) N = 49 | -0.320 | 0.123 | -0.443 |

| Posttreatment | 279.34 (63.52) N = 38 | 327.06 (83.31) N = 44 | 0.024 | -0.066 | 0.090 |

| 3-mo follow-up | 300.75 (80.61) N = 33 | 306.40 (82.17) N = 39 | -0.045 | 0.206 | -0.251 |

| 6-mo follow-up | 297.43 (76.76) N = 26 | 333.83 (77.98) N = 34 | |||

| PSG | |||||

| Baseline | 349.83 (107.27) N = 50 | 344.69 (94.47) N = 50 | |||

| Posttreatment | 347.09 (81.90) N = 38 | 378.29 (94.22) N = 46 | -0.059 | 0.344 | -0.403 |

| 3-mo follow-up | 361.14 (60.34) N = 31 | 360.47 (85.38) N = 38 | 0.094 | 0.137 | -0.043 |

| 6-mo follow-up | 356.60 (74.67) N = 32 | 375.12 (69.65) N = 36 | 0.053 | 0.275 | -0.222 |

| SL | CBT-I | BD | CBT-I | BD | Between Grp. |

| Diary | |||||

| Baseline | 44.53 (32.01) N = 50 | 51.04 (34.76) N = 48 | |||

| Posttreatment | 19.96 (24.30) N = 42 | 25.69 (20.42) N = 48 | -0.704 | -0.772 | 0.068 |

| 3-mo follow-up | 15.74 (9.32) N = 32 | 29.11 (24.20) N = 42 | -0.797 | -0.649 | -0.149 |

| 6-mo follow-up | 20.57 (13.85) N = 32 | 26.86 (23.69) N = 38 | -0.677 | -0.689 | 0.012 |

| Actigraphy | |||||

| Baseline | 28.17 (28.92) N = 47 | 25.66 (21.71) N = 49 | |||

| Posttreatment | 22.79 (23.22) N = 38 | 18.00 (14.84) N = 44 | -0.115 | -0.311 | 0.196 |

| 3-mo follow-up | 30.18 (57.63) N = 33 | 22.60 (17.08) N = 39 | 0.124 | -0.116 | 0.240 |

| 6-mo follow-up | 22.16 (17.59) N = 26 | 22.31 (19.76) N = 34 | -0.088 | -0.144 | 0.056 |

| PSG | |||||

| Baseline | 29.14 (37.24) N = 50 | 34.61 (41.23) N = 50 | |||

| Posttreatment | 30.86 (57.29) N = 38 | 20.03 (17.41) N = 46 | 0.040 | -0.377 | 0.417 |

| 3-mo follow-up | 16.40 (17.17) N = 30 | 25.15 (24.12) N = 38 | -0.335 | -0.241 | -0.094 |

| 6-mo follow-up | 26.25 (36.24) N = 32 | 28.98 (58.85) N = 36 | -0.082 | -0.140 | 0.058 |

| SE | CBT-I | BD | CBT-I | BD | Between Grp. |

| Diary | |||||

| Baseline | .68 (.13) N = 50 | .68 (.15) N = 48 | |||

| Posttreatment | .86 (.12) N = 42 | .83 (.10) N = 48 | 1.328 | 1.107 | 0.221 |

| 3-mo follow-up | .88 (.06) N = 32 | .81 (.12) N = 42 | 1.352 | 0.958 | 0.394 |

| 6-mo follow-up | .85 (.08) N = 32 | .82 (.09) N = 38 | 1.183 | 0.986 | 0.196 |

| Actigraphy | |||||

| Baseline | .65 (.17) N = 47 | .66 (.14) N = 49 | |||

| Posttreatment | .68 (.13) N = 38 | .68 (.14) N = 44 | 0.064 | 0.129 | -0.065 |

| 3-mo follow-up | .69 (.16) N = 33 | .67 (.14) N = 39 | 0.203 | 0.097 | 0.106 |

| 6-mo follow-up | .67 (.15) N = 26 | .69 (.14) N = 34 | 0.080 | 0.167 | -0.087 |

| PSG | |||||

| Baseline | .76 (.14) N = 50 | .73 (.15) N = 50 | |||

| Posttreatment | .83 (.12) N = 38 | .79 (.15) N = 46 | 0.419 | 0.419 | 0 |

| 3-mo follow-up | .81 (.12) N = 30 | .80 (.12) N = 38 | 0.401 | 0.518 | -0.117 |

| 6-mo follow-up | .82 (.11) N = 32 | .79 (.13) N = 36 | 0.409 | 0.397 | 0.012 |

| ISI | CBT-I | BD | CBT-I | BD | Between Grp. |

| Baseline | 16.84 (4.96) N = 49 | 17.18 (5.14) N = 50 | |||

| Posttreatment | 8.87 (5.54) N = 45 | 11.68 (6.92) N = 47 | -1.572 | -1.134 | -0.438 |

| 3-mo follow-up | 10.26 (5.91) N = 33 | 10.93 (5.82) N = 40 | -1.413 | -1.172 | -0.242 |

| 6-mo follow-up | 8.90 (5.99) N = 34 | 12.30 (6.54) N = 40 | -1.527 | -0.902 | -0.625 |

= Primary Outcomes;

CBT-I = Cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia; BD = Behavioral Desensitization (placebo); PSG = polysomnogram; WASO = wake after sleep onset time; TST = total sleep time; SL = Sleep Latency; SE = Sleep Efficiency (total sleep time/time in bed); ISI = Insomnia Severity Index.

Secondary Sleep Outcomes

For diary measures of TST, SL, the ISI, and PSG SE, all mixed-effects models yielded significant overall time effects in the direction of improved sleep (ps < .001). The groups did not differ in rate of improvement over time on any of these measures (ps>.05). No time or group × time interactions were found for actigraphy and PSG measures of TST and SL (ps>.05). See supplemental Table 5 for details.

Primary and Secondary Clinical Pain Outcomes

Table 3 presents the results of the mixed-effects models evaluating the effect of treatment on pain-related outcomes, adjusting for covariates. The PII-D decreased from baseline to 6-month follow-up across all subjects with the BD group decreasing in pain by 6.12 points and the CBT group decreasing by 6.48 points (p<.001). The slope of the change in clinical pain did not significantly differ between the CBT-I and BD groups (p = .12). See Figure 2 D. depicting the significant linear decline in clinical pain overtime. The WOMAC Pain Scale also demonstrated a decrease from baseline to 6-month follow up across all subjects (B = -0.0047, 0.0009, p>.001). There was no differential change in WOMAC pain by group over time (p=.13).

WASO Reductions Predicting Improvements in Clinical Pain

We conducted a mixed-effects model to determine if treatment-related changes in WASO (i.e., from baseline to post-treatment) predicted changes in clinical pain across the post-treatment, 3-, and 6-month follow up time points. Results indicated that baseline-post decreases in diary WASO predicted significantly less pain at post-treatment (B = -8.42, SE = 3.1; z = -2.71, p = .007). This effect increased across the 3- and 6 month follow-up assessment points (B = .03, SE = .01; z = 2.21, p = .027), and was greater for CBT-I compared to BD (B = -.03, SE = .015; z = -2.12, p = .034). Similar effects were observed for PSG WASO, with Baseline-post decreases in PSG WASO associated with decreased clinical pain at post-treatment and 3- and 6-month follow-ups (B = .016, SE = .007, p = .01). This effect was not significantly different between the BD and CBT groups, (B = -.03, SE = .02, p = .09). Treatment-related changes in actigraphically-measured WASO did not significantly predict post-treatment and follow-up changes in clinical pain and, this finding did not vary by treatment group (ps > .26)

QST Measures of Pain Modulation

Table 4 presents the means for both CPM and TS-M at each time point and Table 3, presents the results of the mixed-effects models. Neither CPM (p = .051) nor TS-M (p = .99) significantly changed over time, and the groups did not differ in the slope of change over time for either measure (p = .37 and p = .41, respectively). The trend for CPM suggested that all subjects tended in show a decrease in pain inhibitory capacity over time.

Table 4.

Means and Effects Sizes for Primary and Secondary Pain Outcomes

| Measure | Mean (SD) | Effect Size (d) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diary Pain* | CBT | BD | CBT | BD | Between Grp. |

| Baseline | 47.37 (17.20) N = 48 | 46.76 (18.96) N = 49 | |||

| Posttreatment | 39.81 (21.46) N = 43 | 0.32 (19.07) N = 48 | -0.352 | -0.390 | 0.038 |

| 3-mo follow-up | 35.59 (20.87) N = 36 | 39.79 (22.60) N = 42 | -0.504 | -0.332 | -0.172 |

| 6-mo follow-up | 37.52 (22.50) N = 32 | 36.64 (22.35) N = 37 | -0.428 | -0.518 | 0.091 |

| WOMAC Pain | CBT | BD | CBT | BD | Between Grp. |

| Baseline | 4.65 (2.00) N = 50 | 4.97 (2.45) N = 49 | |||

| Posttreatment | 4.15 (2.29) N = 45 | 4.23 (2.84) N = 48 | -0.21 | -0.33 | 0.12 |

| 3-mo follow-up | 3.53 (2.34) N = 35 | 3.61 (2.81) N = 40 | -0.48 | -0.49 | 0.01 |

| 6-mo follow-up | 4.03 (2.38) N = 36 | 3.54 (2.75) N = 40 | -0.26 | -0.52 | 0.25 |

| CPM | CBT | BD | CBT | BD | Between Grp. |

| Baseline | 1.23 (.28) N = 48 | 1.20 (.23) N = 49 | |||

| Posttreatment | 1.17 (.23) N = 39 | 1.19 (.20) N = 46 | -0.231 | -0.039 | -0.192 |

| 3-mo follow-up | 1.26 (.28) N = 31 | 1.15 (.23) N = 40 | 0.100 | -0.214 | 0.314 |

| 6 -mo follow-up | 1.14 (.19) N = 29 | 1.12 (.21) N = 34 | -0.337 | -0.307 | -0.029 |

| TS | CBT | BD | CBT | BD | Between Grp. |

| Baseline | .09 (.78) N = 50 | -.001 (1.10) N = 49 | |||

| Posttreatment | -.06 (.65) N = 40 | .004 (.72) N = 44 | -0.168 | 0.031 | -0.199 |

| 3-mo follow-up | .10 (.84) N = 31 | .08 (.73) N = 37 | -0.039 | 0.093 | -0.132 |

| 6-mo follow-up | -.13 (.54) N = 34 | -.11 (.40) N = 34 | -0.236 | -0.063 | -0.173 |

Primary Outcomes;

Diary Pain= Pain Intensity Index [(PII-D) 0-100, 0 = no pain]; WOMAC Pain [(0-10), 0=no pain]; CPM = Conditioned Pain Modulation (CPM index = mean pressure pain threshold at the trapezius (PPTh) during cold pressor / mean PPTh trapezius prior to cold pressor, over 4 trials. Values > 1 represent increased pain inhibition, i.e. decreased pain sensitivity). TS = temporal summation of mechanical pain. Values are averaged Z-scores of the wind-up ratios derived from 4 trials by administering two different weighted probes (256 mN and 512 mN) at two anatomic locations (the third digit of the middle phalange and medial patella of the index knee). Higher values indicate increased TS and heightened pain sensitivity.

Clinically Meaningful Changes

Insomnia

We conducted Fisher’s exact tests to evaluate group differences in the proportion of subjects meeting Diary WASO <30 minutes, a common clinical cut off(46). At baseline, 14% and 19% of the CBT-I and BD groups, respectively met this criteria (p>.05). After treatment, significantly more patients randomized to CBT-I (76% posttreatment and 84.4% 3-months) fell within the normal range, compared to BD [48.4%, posttreatment, 52.4% 3-months (ps = .01)]. At 6 months, both groups showed similar clinical improvements [CBT-I = 59% and BD = 61% (p > .05)].

Clinical Pain

On the PII-D, collapsing across groups and all posttreatment time points, 33% of patients reported a 30% reduction in clinical pain, a recommended metric for clinical significance(47). The groups did not differ on the number of patients demonstrating a 30% or greater reduction in clinical pain at any posttreatment time point (p > .05).

Adverse Events

There were no significant between group differences in the emergence of adverse events (AEs) during participation through 6 month follow up. Forty percent randomized to CBT-I reported AEs versus 46% for BD (p = 0.686, Fisher’s Exact Test). The most common AEs were musckuloskeletal problems (39%) and infections (33%). Only three events were judged definitely related to the study, a rash from wearing the actigraph and tenderness at the site of pain testing. Most events were determined to be mild to moderate (81%). Two subjects in both conditions met criteria for serious AEs. All were determined to be unrelated to the study.

DISCUSSION

This double-blinded, randomized, active placebo-controlled clinical trial of CBT-I sought to: 1) evaluate the efficacy of CBT-I in KOA, 2) determine whether improvements in sleep predict reductions in clinical pain severity, and 3) determine whether alterations in laboratory measures of pain modulation mediate sleep-related improvements in clinical pain. We found that both CBT-I and BD yielded significant improvements on objective and subjective measures of sleep and insomnia. Compared to BD, CBT-I demonstrated greater reductions in WASO, the primary sleep outcome, measured via diary, actigraphy and PSG. The observed effect sizes on diary WASO are nearly identical to meta-analytic posttreatment effects for both CBT-I and benzodiazepine receptor agonist (BZRAs) sedative hypnotics in primary insomnia(14). A greater percentage of patients randomized to CBT-I (80%) achieved normative clinical values for diary WASO (< 30 mins.) compared to BD (50%) at posttreatment and 3 months. Both groups showed comparable normative rates by 6 months (60%). The overall differential improvement in WASO across all post and followup assessment periods was 12 -14 minutes (diary and actigraphy, respectively) greater on average per night for CBT-I versus BD. Given the homeostatic, i.e. cumulative effects of sleep disruption and loss over time, this is likely to be a clinically significant differential, comparable to BZRAs sedatives compared placebo. With respect to changes in pain, both groups reported significant and comparable reductions in clinical pain over 6 months with a third of patients demonstrating a clinically meaningful, ≥ 30% reduction in clinical pain severity. Baseline-to-posttreatment reductions in both Diary and PSG WASO predicted decreased clinical pain at posttreatment and at 3- and 6-month follow-up. This effect was significantly greater in the CBT-I group compared to BD. We found no significant changes in laboratory measures of pain modulation (CPM or TS) for either condition.

Effects on Sleep

This trial is the largest to date to evaluate the efficacy of CBT-I as a sole intervention for insomnia in chronic pain and the only study to include PSG measures of outcome. We found large within subject effect sizes for CBT-I and BD over 6 months for all primary and secondary subjective measures of sleep, which were comparable in size to prior studies that tested CBT-I against waitlist and contact control conditions(15-19). Both CBT-I and BD yielded comparable improvements on PSG measured SE and minimal objective improvement on SL or TST.

The current investigation’s use of double blinding and an active placebo extends prior work and strongly supports the use of CBT-I to treat insomnia in KOA. CBT-I yielded significant, moderate between group effects on actigraphy and diary WASO. Our findings contrast somewhat to Edinger et. al’s clinical trial of CBT-I in Primary Insomnia (43). This study found larger treatment effects of CBT-I, due to minimal improvement in the BD condition. The reasons for this discrepancy are unclear, but another study also found that BD yields a substantial treatment effect(48). Given that only a few studies have endeavored to test CBT-I with a behavioral placebo, our finding of a large placebo effect requires continued investigation. It is possible, that the BD intervention, which was initially developed as an active treatment, may in fact contain relatively powerful, active ingredients. This is supported by the maintenance of sleep-related improvement in the placebo condition at the 3-month follow-up. Although we did not measure whether subjects continued to practice behavioral desensitization exercises, as instructed, future research using this condition should explore this possibility. Relatedly we observed some attenuation of treatment effects at 6-month follow-up in both conditions. While this contrasts somewhat from the CBT-I literature in primary insomnia, which generally finds maintenance of sleep effects at 6-months, it is consistent with several of the CBT-I studies in chronic pain populations. Future research should evaluate whether the added complexity of managing insomnia in the context of chronic pain may require periodic booster sessions and / or reinforcement to continue practicing newly learned coping skills to promote long-term maintenance of gains.

Our finding of a large placebo effect for insomnia, however, is consistent with the pharmacotherapy literature for sedative hypnotics in which a substantial portion of the treatment response has been estimated to be due to placebo response(49). Given the potentially dangerous adverse events linked to benzodiazepine receptor agonists and recommendations against their use in older adults(50), the current findings and prior studies indicate that CBT-I should be considered a first line treatment option for insomnia in older adults with KOA. We found that CBT-I demonstrated no differential rate or severity of adverse events compared to BD. Most AEs were mild and judged to be unrelated to the procedures.

Effects on Pain

Although we did not find between group differences on clinical pain, both CBT-I and BD were associated with significant and comparable reductions in clinical pain severity. The nascent literature on the effects of CBT-I on pain has been mixed, with some studies detecting effects on clinical pain(15) and others failing to detect effects(16-20). In general, however, most negative studies found similarly, moderate effect sizes for CBT-I on pain, but sample sizes were small(21). Although the reasons for the mixed findings are not entirely clear, they are also likely due in part to methodological differences, including differing pain conditions studied and limited use of PSG to screen out occult sleep disorders.

Our finding that pre-post treatment changes in Diary and PSG WASO predicted decreased pain at all study endpoints indicates that pain reduction is in part related to improvements in sleep. This is consistent with a recent secondary analysis of the Lifestyles RCT in which all subjects, irrespective of treatment condition, demonstrating a > 30% posttreatment improvement on the ISI, reported significant reductions in pain at followup(24). Taken together, these data support the potential benefit of targeting sleep via psychological methods to improve long-term pain outcomes in OA.

The mechanisms by which improvements in sleep confer improvements in pain, however, remain unclear. We did not find significant evidence that laboratory measures of either CPM or TS were altered by improvements in sleep. It should be noted, however, that this study was powered to detect moderate effect sizes on CPM and TS. The effects observed at some of the time points for these parameters were smaller (d=.19-.30), requiring larger sample sizes to resolve these effects. Several studies have found sleep disruption to be associated with impaired pain inhibitory capacity(12;13). It is unclear whether greater improvements in sleep or a longer follow up timeframe would evidence greater improvements on measures of pain modulation. Although the mechanisms by which improved sleep yielded clinically significant reductions in pain remain largely unclear, future studies might determine whether pain outcomes in KOA may be improved by combining CBT-I with pharmacotherapies, such as selective serotonin norepinephrine inhibitors (SNRIs), which target central pain modulation, but do not consistently improve sleep.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. We did not assess the extent to which interventionists developed expectations / biases about the relative credibility of the BD treatment. It should be noted, however, that unlike traditional pharmacological placebo studies, in which the interventionist is aware of a placebo condition, we deliberately mislead interventionists to believe that both interventions were active. This likely contributed to enhanced placebo effects in the BD condition compared to traditional pharmacological placebo methodology. Although the heterogeneity with respect to intervention training level and gender enhanced generalizability, our small sample size precluded analysis of interventionist characteristics on outcome. Our dropout rate of 27% was less than ideal, though not inconsistent with other studies of CBT-I. We suspect this rate was due in part to the high study burden conferred by multiple PSG assessments and QST. Although not statistically significant, more subjects dropped out of the CBT condition. It is possible that some aspects of the CBT intervention, notably sleep restriction, may be particularly burdensome, which might explain the greater credibility ratings for CBT, but also but also higher drop outs. Finally, since this was an efficacy study with selective inclusion criteria, generalizability of the findings may be limited.

Summary

In this randomized, double-blinded, active placebo controlled trial CBT-I in patients with KOA, we found that both CBT-I and BD were associated with significant improvements in sleep continuity. CBT-I was superior to BD in reducing WASO, the common sleep problem reported by patients with OA. Overall, CBT-I yielded clinically significant improvements on multiple measures of sleep. Both treatment conditions were associated with moderate improvements in pain over 6-month follow-up. Pre-post treatment reductions in WASO predicted subsequent decreases in clinical pain. Measures of pain modulation did not change significantly with treatment. These findings strongly support the efficacy of CBT-I for treating insomnia in OA and highlight that future work is needed to identify the mechanisms by which improvements in sleep improve clinical pain. Given CBT-I’s favorable side-effect profile, screening for insomnia and including CBT-I as a standard treatment component for the substantial number of KOA patients with insomnia, has strong potential to improve the overall management of KOA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00592449

Support: This study was supported by the NIH, National Institutes of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Disease grants: R01 AR05487 & AR059410 (Smith)

Reference List

- 1.Felson DT. An update on the pathogenesis and epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42(1):1–9. v. doi: 10.1016/S0033-8389(03)00161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dieppe PA, Lohmander LS. Pathogenesis and management of pain in osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2005;365(9463):965–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lanes SF, Lanza LL, Radensky PW, Yood RA, Meenan RF, Walker AM, et al. Resource utilization and cost of care for rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis in a managed care setting: the importance of drug and surgery costs. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(8):1475–81. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creamer P, Lethbridge-Cejku M, Hochberg MC. Factors associated with functional impairment in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39(5):490–6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.5.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dominick KL, Ahern FM, Gold CH, Heller DA. Health-related quality of life and health service use among older adults with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(3):326–31. doi: 10.1002/art.20390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilcox S, Brenes GA, Levine D, Sevick MA, Shumaker SA, Craven T. Factors related to sleep disturbance in older adults experiencing knee pain or knee pain with radiographic evidence of knee osteoarthritis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(10):1241–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abad VC, Sarinas PS, Guilleminault C. Sleep and rheumatologic disorders. Sleep Med Rev. 2008;12(3):211–28. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider-Helmert D, Whitehouse I, Kumar A, Lijzenga C. Insomnia and alpha sleep in chronic non-organic pain as compared to primary insomnia. Neuropsychobiology. 2001;43(1):54–8. doi: 10.1159/000054866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clauw DJ, Witter J. Pain and rheumatology: thinking outside the joint. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(2):321–4. doi: 10.1002/art.24326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cruz-Almeida Y, King CD, Goodin BR, Sibille KT, Glover TL, Riley JL, et al. Psychological profiles and pain characteristics of older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65(11):1786–94. doi: 10.1002/acr.22070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finan PH, Buenaver LF, Bounds SC, Hussain S, Park RJ, Haque UJ, et al. Discordance between pain and radiographic severity in knee osteoarthritis: findings from quantitative sensory testing of central sensitization. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(2):363–72. doi: 10.1002/art.34646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith MT, Edwards RR, McCann UD, Haythornthwaite JA. The effects of sleep deprivation on pain inhibition and spontaneous pain in women. Sleep. 2007;30(4):494–505. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.4.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee YC, Lu B, Edwards RR, Wasan AD, Nassikas NJ, Clauw DJ, et al. The role of sleep problems in central pain processing in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):59–68. doi: 10.1002/art.37733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith MT, Perlis ML, Park A, Smith MS, Pennington JY, Giles DE, et al. Comparative meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy and behavior therapy for persistent insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(1):5–11. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vitiello M, Rybakowski J, von Korff M, Stepanski E. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia improves sleep and decreases pain in older adults with co-morbid insomnia and osteoarthritis. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2009;5:355–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edinger JD, Wohlgemuth WK, Krystal AD, Rice JR. Behavioral insomnia therapy for fibromyalgia patients: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(21):2527–35. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.21.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pigeon WR, Moynihan J, Matteson-Rusby S, Jungquist CR, Xia Y, Tu X, et al. Comparative effectiveness of CBT interventions for co-morbid chronic pain & insomnia: a pilot study. Behav Res Ther. 2012;50(11):685–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang NK, Goodchild CE, Salkovskis PM. Hybrid cognitive-behaviour therapy for individuals with insomnia and chronic pain: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2012;50(12):814–21. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Currie SR, Wilson KG, Pontefract AJ, deLaplante L. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of insomnia secondary to chronic pain. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(3):407–16. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jungquist CR, O’Brien C, Matteson-Rusby S, Smith MT, Pigeon WR, Xia Y, et al. The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia in patients with chronic pain. Sleep Med. 2010;11(3):302–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finan PH, Buenaver LF, Runko VT, Smith MT. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Comorbid Insomnia and Chronic Pain. Sleep Mdicine Clinics. 2014;9(2):261–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vitiello MV, McCurry SM, Shortreed SM, Balderson BH, Baker LD, Keefe FJ, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for comorbid insomnia and osteoarthritis pain in primary care: the lifestyles randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(6):947–56. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCurry SM, Shortreed SM, von Korff M, Balderson BH, Baker LD, Rybarczyk BD, et al. Who benefits from CBT for insomnia in primary care? Important patient selection and trial design lessons from longitudinal results of the Lifestyles trial. Sleep. 2014;37(2):299–308. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vitiello MV, McCurry SM, Shortreed SM, Baker LD, Rybarczyk BD, Keefe FJ, et al. Short-term improvement in insomnia symptoms predicts long-term improvements in sleep, pain, and fatigue in older adults with comorbid osteoarthritis and insomnia. Pain. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(8):1039–49. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edinger JD, Bonnet MH, Bootzin RR, Doghramji K, Dorsey CM, Espie CA, et al. Derivation of research diagnostic criteria for insomnia: report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Work Group. Sleep. 2004;27(8):1567–96. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measures. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johns MW. Reliability and factor analysis of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1992;15(4):376–81. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.4.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spitzer R, Gibbon R, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis 1 Disorders. Version 2. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schramm E, Hohagen F, Grasshoff U, Riemann D, Hajak G, Weess HG, et al. Test-retest reliability and validity of the Structured Interview for Sleep Disorders According to DSM-III-R. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(6):867–72. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Redline S, Sanders MH, Lind BK, Quan SF, Iber C, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Methods for obtaining and analyzing unattended polysomnography data for a multicenter study. Sleep Heart Health Research Group. Sleep. 1998;21(7):759–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haythornthwaite JA, Hegel MT, Kerns RD. Development of a sleep diary for chronic pain patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1991;6(2):65–72. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(91)90520-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lichstein KL, Stone KC, Donaldson J, Nau SD, Soeffing JP, Murray D, et al. Actigraphy validation with insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29(2):232–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bastien CH, Vallie’res A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Medicine. 2000;2(2001):297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jensen MP, McFarland CA. Increasing the reliability and validity of pain intensity measurement in chronic pain patients. Pain. 1993;55(2):195–203. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90148-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(12):1833–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Finan PH, Quartana PJ, Smith MT. Positive and negative affect dimensions in chronic knee osteoarthritis: effects on clinical and laboratory pain. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(5):463–70. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31828ef1d6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arendt-Nielsen L, Petersen-Felix S. Wind-up and neuroplasticity: is there a correlation to clinical pain? Eur J Anaesthesiol Suppl. 1995;10:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perlis ML, Jungquist C, Smith MT, Posner D. Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Insomnia: A Session-by-Session Guide. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lacks P, Bertelson AD, Sugerman J, Kunkel J. The treatment of sleep-maintenance insomnia with stimulus-control techniques. Behav Res Ther. 1983;21(3):291–5. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(83)90211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edinger JD, Wohlgemuth WK, Radtke RA, Marsh GR, Quillian RE. Cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of chronic primary insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285(14):1856–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.14.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borkovec TD, Nau SD. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1972;2:257–60. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singer JD, Willet JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. London: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morin CM. Insomnia: Psychological Assessment and Management. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, Beaton D, Cleeland CS, Farrar JT, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9(2):105–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lichstein KL, Riedel BW, Wilson NM, Lester KW, Aguillard RN. Relaxation and sleep compression for late-life insomnia: a placebo- controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(2):227–39. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huedo-Medina TB, Kirsch I, Middlemass J, Klonizakis M, Siriwardena AN. Effectiveness of non-benzodiazepine hypnotics in treatment of adult insomnia: meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. BMJ. 2012;345:e8343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.