Abstract

This report presents a case of stroke-like migraine attacks after radiation therapy (SMART) syndrome in a 31-year-old man in whom symptoms and radiological findings resolved with steroid pulsed therapy and reviews the literatures with special emphasis on the use of steroids against SMART syndrome. The patient had a past history of left temporal anaplastic astrocytoma and was treated with surgery followed by local 72 Gy radiation therapy and chemotherapy using Nimustine Hydrochloride. Four years after the surgery, he was suffering from subacute progressing symptoms of headache, right hemianopia, right hemiparesis and aphasia from 2 to 4 days before admission to our hospital. At first he was diagnosed as symptomatic epilepsy but after extensive examination, the final diagnosis was SMART syndrome. His symptoms soon improved with steroid pulse therapy. In the literature, steroid pulse therapy is not necessarily a standard of care for SMART syndrome, but it seemed to decrease the need of biopsy. As the lesions of SMART syndrome require differential diagnosis from recurrences, biopsy was performed in some cases. However, lack of benefit and possible detriment is reported with biopsy of SMART lesions. Through this experience we suggest that steroid pulse therapy may provide speedy recovery from symptoms, and it should be considered before other invasive investigations or treatments.

Keywords: Glioma, Radiation, SMART syndrome, Steroid pulse therapy

Highlights

-

•

Report a case of stroke-like migraine attacks after radiation therapy (SMART) syndrome in a 31-year-old man in whom symptoms and radiological findings resolved with steroid pulsed therapy.

-

•

Lack of benefit and possible detriment is reported with biopsy of SMART lesions.

-

•

Steroid pulse therapy is not necessarily a standard of care for SMART syndrome, but it seemed to decrease the need of biopsy.

-

•

Steroid pulse therapy may provide recovery from symptoms of SMART, and should be considered before invasive investigations.

1. Introduction

SMART (stroke-like migraine attacks after radiation therapy) is a syndrome presumed to be a delayed complication of brain irradiation wherein patients have recurrent attacks of complex neurological symptoms, often including headache and seizures that begin many years after radiation therapy, and demonstrates characteristic imaging findings [1]. Since it was first described in 1995, about 40 cases of SMART have been reported in the literature [2]. Given the small number of cases reported to date, there is no clear consensus regarding effective treatment approaches to SMART.

2. Case presentation

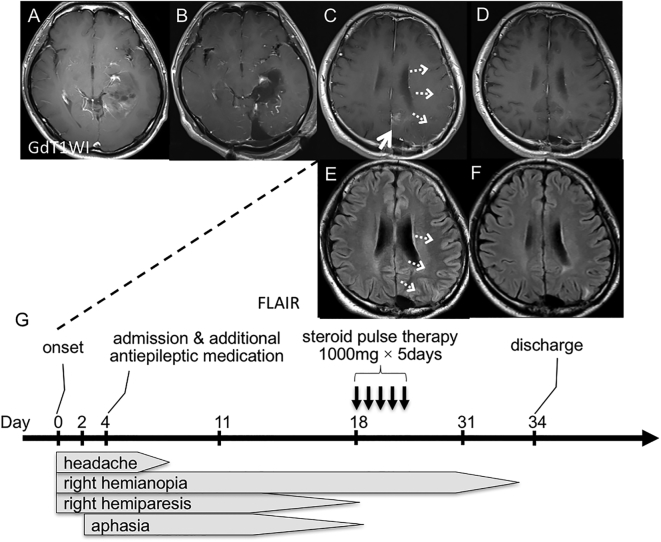

A 31-year-old man, who had a past history of left temporal anaplastic astrocytoma, was then followed consistently with MRI at our outpatient department. He had initially been treated with surgery (Fig. 1, A, B) followed by local 72 Gy radiation therapy and chemotherapy using Nimustine Hydrochloride. After the treatment he had a right upper quadrantanopia but discharged without any other neurological deficit. He had received 12 cycles of maintenance ACNU therapy given once in 2 months and was then followed consistently. During this period, his symptomatic epilepsy was well controlled with levetiracetam and carbamazepine. Four years later, however, he suffered from subacute progressing symptoms of headache, right hemianopia, right hemiparesis and aphasia. MRI scan obtained on admission revealed abnormal findings, including new enhancement at left parietal lobe, and mild swelling of left frontal, parietal, and temporal gyri (Fig. 1, C, E). At first, he was treated with additional antiepileptic medication, because the electroencephalogram revealed focal slowing over the left frontal to temporal region. Nevertheless, his symptoms persisted for several days, especially his worsened visual field defect persisted for over 2 weeks. With the possible diagnosis of SMART, steroid pulse therapy (1000 mg/day, 5 days) was given. Subsequently, his visual field recovered to almost the similar level as before within only 2 weeks. Additionally, the abnormal imaging findings including enhancement and swelling had also disappeared on a subsequent MRI (Fig. 1, D, F). Clinical course of the present case is summarized in Fig. 1, G.

Fig. 1.

Imaging findings with the clinical course.

Patient's preoperative T1-weighted image (T1WI) with contrast enhancement shows a left temporal anaplastic astrocytoma (A). Postoperative examination demonstrates removal of the lesion (B). T1WI with contrast enhancement and FLAIR (fluid attenuated inversion recovery) signal on admission revealed new enhancement at left parietal lobe (C, white arrow), and mild swelling of left frontal and temporal gyri (C, E, white dashed arrows). Three days after steroid pulse therapy, the enhancement and swelling had disappeared (D, F). Clinical course (G).

3. Discussion

SMART is a rare complication of brain radiotherapy with delayed onset of complex neurological impairment unrelated to tumor recurrence. Our case fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for SMART which was revised by Black et al., in 2006 [3]. According to the literature, the interval between radiotherapy and the diagnosis of SMART ranges from 1 to 35 years [2]. This new neurological deficits and new enhancement regions in MRI long after the initial treatment lead a neurologist to think first about recurrence of malignancy. In case they are tumor recurrence, rapid diagnosis and initiation of appropriate treatment is the utmost importance because patients with recurrent malignant gliomas often deteriorate rapidly. Therefore, differential diagnosis from recurrence is extremely important.

The hallmark features of SMART on MRI are reversible, transient, unilateral cortical gadolinium enhancement as well as the correlative abnormal T2 and FLAIR (fluid attenuated inversion recovery) signal [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. However, in most cases, MRI abnormalities persist over weeks to months [4]. The differential diagnosis from recurrence cannot wait until after several months. In some cases, patient reluctantly underwent biopsy for early diagnosis [4]. Recently Black et al. reported that they failed to demonstrate pathologic etiology of SMART from biopsy, and warned the lack of benefit and possible detriment [4]. In the present case, the abnormal imaging findings had disappeared within only 3 days from steroid pulse therapy. Patient's persistent symptom had also recovered within only 2 weeks. Therefore, steroid pulse therapy can be recommended in the case of possible SMART for earlier determination of SMART from non-SMART including recurrence. “Blood-brain barrier disruption” in SMART is described in some literatures, possibly leading to edema or inflammation in the nervous system [1,4]. Steroid therapy can be reasonable from this point of view.

In the literature, SMART syndrome is treated either with (Table 1) or without (Table 2) steroid therapy. Prognosis of SMART syndrome is not poor even without steroid therapy; almost all cases recovered at least partially (Table 2). Therefore, steroids are not considered as standard of care. However, biopsy seems to have performed more often in the non steroid group. As mentioned above, lack of benefit and possible detriment is reported with biopsy of SMART lesion [4]. Steroid therapy may help earlier diagnosis and prevent the unnecessary surgical procedure.

Table 1.

Cases of SMART treated with steroids.

| Author, year [ref] | Treatment | Recovery period after treatment | Outcome | Biopsy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black, 2013 [4] | 2 cases: corticosteroids | Undescribed | Partially recovered | 1/2 biopsy |

| 1 case: antiepileptic drugs + corticosteroids | 2.5 months | Completely recovered | – | |

| 2 cases: antiepileptic drugs + varapamil + corticosteroids | 2–2.5 months | Completely recovered | – | |

| Di Stefano, 2013 [5] | 1 case: antiepileptic drugs + methylprednisolone (1000 mg/day, 5 days) | 4 days | Partially recovered | – |

| 3 cases: antiepileptic drugs + methylprednisolone (1000 mg/day, 5 days) | 2–5 days | Completely recovered | – | |

| 1 case: antiepileptic drugs + dexamethasone 20 mg daily | 6 days | Partially recovered | – | |

| Maloney, 2014 [6] | 1 case: antiepileptic drugs + temporal lobectomy + dexamethasone (20 mg/day) | 4 days | Completely recovered | – |

| Hametner,2015 [7] | 1 case: antiepileptic drugs + high dose cortisone therapy + sedation | 2 months | Completely recovered | – |

| Gómez-Cibeira, 2015 [1] | 1 case: antiepileptic drugs + methylprednisolone (1000 mg/day, 5 days) | Several weeks | Completely recovered | – |

| Jaraba, 2015 [8] | 1case: antiepileptic drugs + high dose corticosteroid therapy (1 mg/kg/day) + sedation | Few days | Partially recovered but died of pneumonia | – |

| 1case: antiepileptic drugs + high dose corticosteroid therapy (1 mg/kg/day) | 1 week | Completely recovered | – | |

| 1case: antiepileptic drugs + high dose corticosteroid therapy (1 mg/kg/day) | 11 days | Completely recovered | – | |

| Nar Senol, 2015 [9] | 1 case: antiepileptic drugs + dexamethasone | 2 weeks | Completely recovered | – |

| Singh, 2016 [10] | 1 case: antiepileptic drugs + corticosteroids | – | Permanent disability | – |

| Present case | 1 case: antiepileptic drugs + steroid pulse therapy (1000 mg/day, 5 days) | 2 weeks | Completely recovered | – |

Ref; reference.

Steroid therapies and outcomes in reported SMART cases. In 5 cases who received steroid pulse therapy (1000 mg/day, 5 days), complete recovery was observed in 4 cases (80%) whereas only1 case (20%) just had partial recovery.

Table 2.

Cases of SMART treated without steroids.

| Auther, year [ref] | Treatment | Recovery period after treatment | Outcome | Biopsy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friedenberg, 2000 [11] | 1 case: antiepileptic drugs + asprin | Several weeks | Partially recovered | – |

| Bartleson, 2003 [12] | 1 case: antiepileptic drugs | Several weeks | Completely recovered | – |

| 1 case: antiepileptic drugs + varapamil + warfarin | Several weeks | Completely recovered | – | |

| Black, 2006 [13] | 1 case: antiepileptic drugs + varapamil | Several weeks | Completely recovered | – |

| 1 case: antiepileptic drugs | 3–4 weeks | Completely recovered | – | |

| Cordato, 2006 [14] | 1 case: antiepileptic drugs | 1–2 months | Completely recovered | – |

| 1 case: antiepileptic drugs | 2 days | Completely recovered | – | |

| Abend, 2009 [15] | 1 case: antiepileptic drugs | 2 weeks | Completely recovered | – |

| Kerklaan, 2011 [16] | 1 case: antiepileptic drugs | Several weeks | Completely recovered | – |

| 2 cases: antiepileptic drugs | Few days | Completely recovered | – | |

| 1 case: antiepileptic drugs + sedation | Several weeks | Completely recovered | open biopsy | |

| Diniz Fde, 2013 [17] | 1 case: no specific therapy | Undescribed | Completely recovered | – |

| Black, 2013 [18] | 1 case: antiepileptic drugs | Undescribed | Partially recovered | Biopsy |

| 1 case: antiepileptic drugs | 1–2 months | Completely recovered | – | |

| 1 case: antiepileptic drugs + asprin | Undescribed | Partially recovered | Biopsy | |

| 2 cases: antiepileptic drugs + verapamil | 2 months | Completely recovered | – | |

| 1 case: antiepileptic drugs + varapamil + asprin | Undescribed | Partially recovered | Biopsy | |

| Lim, 2016 [19] | 1 case: antiepileptic drugs + sedation | 2.5 months | Partially recovered | – |

| Ramanathan, 2016 [3] | 1 case: antiepileptic drugs + acyclovir | Few days | Completely recovered | – |

| Rigamonti, 2016 [20] | 1 case: antiepileptic drugs | 5 months | Completely recovered | – |

| O'Shea A, 2016 [21] | 1 case: Undescribed | Few months | Completely recovered | – |

Ref; reference.

Although, there exist several reports that just had incomplete recovery after steriod therapy, the dose of steroid is not specified in many of the reports. Some of the cases who received corticosteroid therapy but not pulse therapy had partial recovery (Table 1) [4,5]. In 5 cases who received steroid pulse therapy (1000 mg/day, 5 days), including the present case, complete recovery was observed in 4 cases (80%) but 1 case (20%) just had partial recovery (Table 1) [5].

We reported a case of SMART whose persistent symptom responded rapidly to steroid pulse therapy. Through this experience and review of the literature, we suggest that steroid pulse therapy may provide speedy diagnosis of and recovery from SMART, and it should be considered before other invasive investigations or treatments.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gómez-Cibeira E., Calleja-Castaño P., Gonzalez de la Aleja J. Brain magnetic resonance spectroscopy findings in the stroke-like migraine attacks after radiation therapy (SMART) syndrome. J. Neuroimaging. 2015;25(6):1056–1058. doi: 10.1111/jon.12227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khanipour Roshan S., Salmela M.B., McKinney A.M. Susceptibility-weighted imaging in stroke-like migraine attacks after radiation therapy syndrome. Neuroradiology. 2015;57(11):1103–1109. doi: 10.1007/s00234-015-1567-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramanathan R.S., Sreedher G., Malhotra K. Unusual case of recurrent SMART (stroke-like migraine attacks after radiation therapy) syndrome. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2016;19(3):399–401. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.168634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black D.F., Morris J.M., Lindell E.P. Stroke-like migraine attacks after radiation therapy (SMART) syndrome is not always completely reversible: a case series. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2013;34(12):2298–2303. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Stefano A.L., Berzero G., Vitali P. Acute late-onset encephalopathy after radiotherapy: an unusual life-threatening complication. Neurology. 2013;81(11):1014–1017. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a43b1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maloney P.R., Rabinstein A.A., Daniels D.J. Surgically induced SMART syndrome: case report and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2014;82(1–2) doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2013.01.028. (240.e7–12) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hametner E., Unterberger I., Lutterotti A. Non-convulsive status epilepticus with negative phenomena—a SMART syndrome variant. Seizure. 2015;25:49–51. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaraba S., Puig O., Miró J. Refractory status epilepticus due to SMART syndrome. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;49:189–192. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nar Senol P., Gocmen R., Karli Oguz K. Perfusion imaging insights into SMART syndrome: a case report. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2015;115(4):807–810. doi: 10.1007/s13760-015-0483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh D., Hsu C.C. Stroke-like migraine attacks after radiation therapy (SMART) syndrome causing permanent neurological deficit. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2016;19(1):129–130. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.165484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedenberg S., Dodick D.W. Migraine-associated seizure: a case of reversible MRI abnormalities and persistent nondominant hemisphere syndrome. Headache. 2000;40(6):487–490. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartleson J.D., Krecke K.N., O'Neill B.P. Reversible, strokelike migraine attacks in patients with previous radiation therapy. Neuro-Oncology. 2003;5(2):121–127. doi: 10.1215/S1522-8517-02-00040-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Black D.F., Bartleson J.D., Bell M.L. SMART: stroke-like migraine attacks after radiation therapy. Cephalalgia. 2006;26(9):1137–1142. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cordato D.J., Brimage P., Masters L.T. Post-cranial irradiation syndrome with migraine-like headaches, prolonged and reversible neurological deficits and seizures. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2006;13(5):586–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abend N.S., Florance N., Finkel R.S. Intravenous levetiracetam terminates refractory focal status epilepticus. Neurocrit. Care. 2009;10(1):83–86. doi: 10.1007/s12028-007-9044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerklaan J.P., Lycklama á Nijeholt G.J., Wiggenraad R.G. SMART syndrome: a late reversible complication after radiation therapy for brain tumours. J. Neurol. 2011;258(6):1098–1104. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5892-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diniz Fde V., Lopes L.C., Castro L.H. SMART syndrome: a late reversible complication of radiotherapy. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2013;71(5):336–337. doi: 10.1590/0004-282x20130033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Black D.F., Morris J.M., Lindell E.P. Stroke-like migraine attacks after radiation therapy (SMART) syndrome is not always completely reversible: a case series. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2013;34(12):2298–2303. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim S.Y., Brooke J., Dineen R. Stroke-like migraine attack after cranial radiation therapy: the SMART syndrome. Pract. Neurol. 2016;16(5):406–408. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2016-001385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rigamonti A., Lauria G., Mantero V. SMART (stroke-like migraine attack after radiation therapy) syndrome: a case report with review of the literature. Neurol. Sci. 2016;37(1):157–161. doi: 10.1007/s10072-015-2396-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Shea A., Culleton S., Asadi H. A diagnosis of stroke-like migraine attacks after radiation therapy (SMART) as severe headache with stroke-like presentation. Iran J. Neurol. 2016;15(4):237–239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]