Abstract

The periodontal pathogen Tannerella forsythia has the unique ability to produce methylglyoxal (MGO) an electrophilic compound, which can covalently modify amino acid side chains and generate inflammatory adducts known as advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs). In periodontitis, the concentrations of gingival-crevicular fluid MGO increase, and correlate with the levels of T. forsythia load. However, the source of MGO and the extent to which MGO may contribute to periodontal inflammation has not been fully explored. In this study, we identified a functional homolog of methyl glyoxal synthase enzyme (MgsA) involved in the production of MGO in T. forsythia. While the wild-type T.forsythia produced significant amount of MGO in the medium, a mutant lacking this homolog produced little to no MGO. Furthermore, compared to the T. forsythia parental strain spent medium, the T. forsythia mgsA-deletion strain spent medium induced significantly lower NF-kB activity as well as pro-inflammogenic and pro-osteoclastogenic cytokines from THP-1 monocytes. The ability of T. forsythia to induce protein glycation end products via MGO was confirmed by an electrophoresis based collagen chain mobility shift assay. Together these data demonstrated that T. forsythia produces MGO, which may contribute to inflammation via the generation of AGEs, and thus acts as a potential virulence factor of the bacterium.

Keywords: T. forsythia, Methylglyoxal, AGEs, RAGE, Periodontitis

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis (PD) results from chronic inflammation of the tooth supporting apparatus due to the presence of subgingival microbial community, which exhibits polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis1. Clinical and experimental evidence has established that the so called ‘red complex’ consortium comprising of Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia and Treponema denticola plays a dominant role in the development of PD2. PD is a leading cause of tooth loss and is estimated that some forms of this disease affect more than 50% of population worldwide. In addition, evidence indicates that PD contributes to the pathogenesis of systemic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases (CVD), rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and diabetes3–10. The periodontal pathogen T. forsythia has adapted to the human oral niche at least since the emergence of prehistoric Neolithic humans11. Despite the epidemiological and experimental evidence implicating T. forsythia in the pathogenesis of PD12, it has remained an understudied organism partly due to its demanding growth requirements and resistance to genetic manipulations in the laboratory. While a number of virulence determinants of T. forsythia have been investigated13, its unique ability to produce methylglyoxal (MGO)14 is worthy of further examination since the contribution of T. forsythia released MGO and its mechanistic relationship to PD pathogenesis has not been investigated. MGO is an electrophilic compound which by covalently modifying the side chain amino groups of lysine, arginine and thiol group of cysteine in proteins can generate inflammatory adducts known as the advanced glycation endproducts or AGEs. AGEs are inflammogenic molecules as they activate RAGE (receptor for AGEs) on macrophages and endothelial cells to induce the release of inflammatory cytokines. MGO accumulation is associated with several inflammatory pathologies including atherosclerosis, diabetes and aging related diseases with an inflammatory etiology. In these diseases, MGO accumulates in the body mainly as a by-product of the host glycolysis and/or secretion by the gut microbiota15,16. With regard to PD, the severity of disease has been shown to correlate with levels of MGO and red-complex bacteria, including T. forsythia17. The purpose of this study was to characterize and define the role of MGO produced by T. forsythia. In this study, we identified a functional ortholog of methyl glyoxal synthase (Tf MgsA) of T. forsythia and showed that MGO produced by T. forsythia can induce AGE adduct formation, which may promote inflammation in the periodontal setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

T. forsythia ATCC 43037 was grown in TF-broth (TFB; brain heart infusion media containing 5 µg /ml hemin, 0.5 µg/ml menadione, 0.001% N -acetylmuramic acid, 0.1% L-cysteine and 5% fetal bovine serum) as liquid cultures or on plates containing 1.5 % agar in broth under anaerobic conditions as described previously18. An isogenic T. forsythia mutant TFM-1726 inactivated of mgsA gene encoding methylglyoxal synthase (construction described below) was grown in broth or agar plates containing 5 µg/mL erythromycin.

Construction of MgsA inactivated strain

The open-reading frame BFO_1726 in T. forsythia annotated as a predicted homolog of methylglyoxal synthase (MgsA) in the genome database (http://img.jgi.doe.gov) was targeted for insertional inactivation with an erythromycin (Emr) cassette as per previously described protocol19,20. Briefly, a DNA fragment containing the ermF gene flanked by the upstream and downstream regions of the BFO_1726 was generated by overlap extension PCR using the primer sets listed in Table 1. To obtain this fragment, the 5’- and 3’- regions of BFO_1726 were amplified with the primer sets TfmgsA1F/TfmgsA3R and TfmgsA6F/TfmgsA2R, respectively, from the T. forsythia 43037 genomic DNA. The ermF fragment was amplified by PCR with the primer set TfmgsA4F/TfmgsA5R from the pVA2198 plasmid DNA21. All three DNA fragments were combined and an overlap PCR reaction was carried out with the primer set TfmgsA1F /TfmgsA2R to yield a 3741 bp fragment, which was gel purified and used for transformation of T. forsythia ATCC 43037 by electroporation. Em resistant colonies were analyzed by PCR, DNA sequencing and RT-PCR to confirm correct integration and to rule out polar effects. One such isogenic mutant, named TFM-1726 was selected for future analysis.

Table 1.

List of primers used in the study

| Primer | DNA sequence (‘5-‘3) | |

|---|---|---|

| TfmgsA 1F | GCGCCTTTTCGATTAACG | |

| TfmgsA 2R | ATGGAGCATCGTGCTCGGA | |

| TfmgsA 3R | CAATTTCTTTTTTGTCATATCGTCAGTTTTTATGTATTCGTAC | underlined text indicates overlap region with ermF |

| TfmgsA 4F | ATAAAAACTGACGATATGACAAAAAAGAAATTGCCC | underlined text indicates overlap region with Tf43037 genomic DNA |

| TfmgsA 5R | TAGCGATATCCCGCTCTACGAAGGATGAAATTTTTC | underlined text indicates overlap region with Tf43037 genomic DNA |

| TfmgsA 6F | TTTCATCCTTCGTAGAGCGGGATATCGCTAAAAAGT | underlined text indicates overlap region with ermF |

Characterization of methylglyoxal production

MGO in spent media from the T. forsythia 43037 and TFM-1726 strains was quantified by an ELISA kit (MGO Competitive EIA Kit, LifeSpan Biosciences) as per manufacturer’s instructions and by a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) based quantitative assay described by McLellan et al.22 with minor modifications. Briefly, trichloroacetic acid (10% final concentration) precipitation was carried out to remove proteins from the media prior to derivatization with 1, 2-diamino-4, 5-dimethoxybenzene and HPLC of the resulting quinoxaline, 6, 7-dimethoxy-2-methylquinoxaline with fluorescence detection. Hexanedione was used as the quantitative internal standard. Derivatization and HPLC were performed under acid conditions and in the presence of sodium azide to prevent the spontaneous formation of methylglyoxal from glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone and to inhibit endogenous peroxidases, respectively.

Glycated endproduct analysis by SDS-PAGE

Collagen was used as the target protein for assessing MGO mediated glycation as previously described23,24. Briefly, wells of a 48-well tissue culture plates coated with Bovine type-1 Collagen Solution (100 µg/100 µl/well) with 1 part of chilled neutralization buffer (Advanced BioMatrix, Inc. Carlsbad, CA) and then incubated for 1 h at 37°C to facilitate gel formation24. The wells were incubated with commercial MGO, bacterial cell free culture supernatants and TF broth at different concentrations for 48 hrs. at 37°C. The wells after treatment with culture supernatants were aspirated, and bound collagen was extracted in 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 70°C and subsequently analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (8% gels) under reducing conditions and silver staining.

NF-kB/AP-1 inducible secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) activity

THP-1-Blue cells (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 4.5 g/L glucose, 100 U/ml penicillin G, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. THP1-Blue cells are derived from the human monocytic THP-1 cell line by stable transfection with a reporter plasmid expressing a secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) gene under the control of NF-κB and AP-1 inducible promoter. Mammalian cells were seeded in 48-well culture plates at a density of 105 cells per well in 250 µl growth medium. THP1-Blue cells were then challenged in triplicate with cell-free supernatant (20 µl/well) from either the mid-log phase wild-type (Tf43037) or TFM-1726 culture for 12 h. For antibody blocking experiments, culture supernatants were incubated in the presence of a function blocking anti-RAGE mouse monoclonal antibody (10 µg/ml). This antibody was generated by cloning the variable regions of heavy and light chains of anti-RAGE rabbit mAb H425 into pFUSE-CHIg-mG1 and pFUSE2-CLIg-mK vectors (Invivogen) to express as a mouse mAb. The recombinant H4 mAB was then produced in 293F cells and purified by protein-G affinity column (Xu et al., unpublished). In parallel wells, a mouse isotype IgG (10 µg/ml) was used as a control. Sterile TFB medium (20 µl/well) was used as a MGO-negative control. Preliminary experiments in our laboratory indicated that when TFB broth greater than 10% of total THP-1 culture volume was used, the viability of THP-1 cells reduced significantly after 16 h incubation as judged by trypan blue staining. We chose TFB broth volume at 10% of total culture volume in all future experiments since at this level >95% of THP-1 cells were found to be viable. HMGBI (high-mobility group box 1 protein)26 was used as a positive control ligand of RAGE. After stimulation, supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C until assayed for SEAP activity by a colorimetric enzyme assay (Quanti-Blue, InVivogen Inc.).

Quantification of Cytokine levels

Culture supernatants were collected from THP-1 cells after challenge with bacterial culture supernatants and or modified collagen as above to assess the levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 by BioPlex-MAGPIX (Bio-Rad) and ELISA kits (Life Technologies Corporation, Frederick, MD) as per manufacturer instructions respectively. Supernatants were used as undiluted and 1:10 fold dilutions. The detection limit for all cytokines was 5 pg /mL.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed on Graph Pad Prism software (Graph Pad, San Diego, CA). Comparisons between groups were made using analysis of variance with an appropriate post hoc t test to compare groups. Statistical significance is defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Inactivation of mgsA impairs methylglyoxal production in T. forsythia

The BFO_1726 open-reading frame in T. forsythia is a predicted ortholog of methylglyoxal synthase (MgsA) involved in MGO synthesis. Strikingly, the red-complex partners of T. forsythia, P. gingivalis and T. denticola do not possess a homolog of MgsA. To confirm the functionality of BFO_1726 as a bona-fide MgsA, we constructed a deletion mutant and compared its ability to secrete active MGO. One representative isogenic mutant, TFM-1726, was selected and compared to the parental strain relative to MGO production. The results of the ELISA based assay showed that TFM-1726 produced significantly reduced amount of MGO than the parental strain ATCC 43037 (Fig. 1a). These results were confirmed with a HPLC based quantitative assay. Fig. 1b shows representative chromatogram traces for each of the wild-type and mutant strain culture supernatants. MGO peak areas were used to calculate the amounts of MGO from a calibrated standard curve. The average MGO levels calculated from two independent cultures grown on separate days, each assayed in triplicate were as follows (mean ± s.d.); wild-type 42.9 ± 2.7 ng/ml (P < 0.01, versus TFM-1726 and culture medium alone); TFM-1726. 11.4 ± 0.8 ng/ml (not significant, versus culture medium alone), and; sterile culture medium, 9.9 ± 1.1 ng/ml (basal level). Thus, the level of MGO in the wild-type culture supernatant was ~4-fold higher than that in the TFM-1726 or sterile medium. The presence of MGO even in the sterile medium (basal level) although is intriguing, but is probably due to the non-enzymatic conversion of glucose27 and/or from the fetal bovine serum used in the preparation of TF Broth. Taken together, we showed that inactivation of BFO_1726 (Tf mgsA) impairs the production of MGO from T. forsythia.

Fig. 1. Methylglyoxal production by T. forsythia.

MGO in the spent media from the wild-type (Tf43037) and the mutant TFM-1726 strains was estimated by ELISA (a) and HPLC (b); sterile medium (TFB) was used as control. For HPLC, MGO was measured as the 6, 7-dimethoxy-2-methylquinoxaline derivative and Hexanedione (HDO) used as an internal standard was measured as 6, 7-dimethoxy-2-methyl-3-pentylquinoxaline derivative. *P< 0.05 ***P< 0.001.

T. forsythia MGO forms glycated collagen

Next, the ability of T. forsythia culture supernatants to induce the formation of advanced glycation endproducts was assessed. For this purpose, type I collagen was subjected to SDS-PAGE following treatment with cell-free bacterial culture supernatants. TF broth and commercial MGO were used for negative and positive treatment controls, respectively. The migration pattern of collagen chains was compared to untreated collagen samples as previously described24,28. The results showed the formation of glycated collagen end products by the wild-type culture supernatant in a dose dependent manner as judged by the shift in the molecular size of α1 and α2 collagen chains (Fig. 2, lanes 7 & 8) compared to the untreated collagen (Fig. 2, lanes 2) or the collagen treated with the sterile medium (Fig. 2, lanes 5 & 6) or the spent medium from TFM-1726 culture (Fig. 2, lanes 9 & 10). The full gel image is available online in the supplementary material (Fig. S1).

Fig. 2. T. forsythia produced MGO promotes collagen glycation.

48-well cell culture plates were coated with a bovine type-I collagen solution for 1 h at 37°C. The collagen matrix was then incubated with either commercial MGO (1 mM and 5 mM), spent medium (50 and 100 µl) from Tf43037 or TFM-1726 culture, or sterile TFB for 48 h at 37°C. Collagen matrix wells were washed twice with water and collagen fibrils were extracted with 5% SDS and separated by SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining.

T. forsythia MGO drives glycation adduct formation to induce pro-inflammatory cytokine production via RAGE

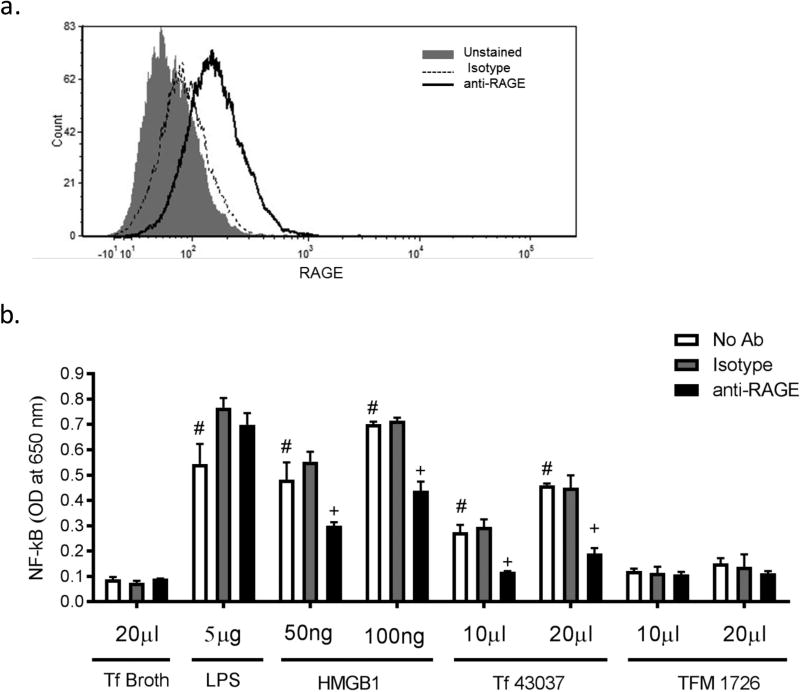

MGO and MGO-derived glycated adducts can activate nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways in endothelial cells and leucocytes, driving inflammatory cytokine release29–32. To assess the immunogenic potential of T. forsythia MGO induced AGE adducts, we utilized THP1-Blue reporter cells in which inflammatory receptor induced NF-kB activation can be monitored by assaying for secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP)33,34. Importantly, we confirmed that RAGE receptor, which can induce NF-kB, is indeed expressed on the surface of THP-1 monocytes. As demonstrated by the flow cytometric data (Fig. 3a), THP- 1 cells were specifically stained with a RAGE-specific monoclonal antibody but not with an isotype control antibody. Regarding RAGE receptor activation, our data clearly showed that while the culture supernatant from the wild-type strain was able to activate NF-kB, the culture supernatant from the mutant TFM-1726 at similar dilutions was ineffective (Fig. 3b). In addition, the anti-RAGE monoclonal antibody significantly blocked the wild-type culture supernatant induced NF-kB. As expected, anti-RAGE antibody blocked the activity of a RAGE ligand, HMGB1 (High-mobility group box 1 protein)26, and not of E. coli LPS used as a non-RAGE ligand.

Fig. 3. T. forsythia-MGO derived glycation adducts activate RAGE.

(a) Flow cytometric analysis of RAGE expression in THP-1 cells. THP-1 Blue cells stained with either anti-RAGE monoclonal antibody or an isotype control (mouse IgG1) followed by FITC-conjugated rat anti-mouse IgG antibody were analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometric image of THP-1 cells is shown. (b) RAGE activation by T. forsythia. THP1-Blue reporter cells were stimulated with spent culture supernatants from the parental (Tf43037) and mutant (TFM-1726) strains in the presence or absence of either an anti-RAGE monoclonal or a mouse isotype control antibody. After 12 h incubation, NF-κB activation was assessed by measuring the levels of SEAP enzyme activity in the supernatant. HMGB1 and E. coli LPS were used as RAGE and TLR4 agonist controls, respectively. TFB medium was used as a control. Data represent one of three independent experiments with similar results. #, P<0.01 versus broth (TFB) stimulated control, +, P<0.05 versus no antibody and isotype antibody controls (n=3).

To confirm the inflammogenic potential of T. forsythia derived MGO, we assayed the levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines from THP-1 monocytic cells following stimulation with spent culture supernatants and T. forsythia-modified glycated collagen adducts obtained above. The data showed that levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α were significantly higher in THP-1 cell supernatants stimulated with the wild-type (ATCC 43037) strain compared to the TFM-1726 mutant (Fig.4A). Interestingly, the levels of IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, did not show any significant difference between the wild-type and TFM-1726 culture supernatant activated cells. In addition, collagen treated with T. forsythia wild-type supernatant was significantly more active than the collagen treated with TFM-1726 supernatant in inducing secretion of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in THP-1 cells (Fig. 4b). TFM-1726 spent medium treated collagen showed significantly higher cytokine inducing activity compared to the sterile TFB medium treated collagen (Fig. 4b). The cause of increased cytokine inducing activity of TFM-1726 spent medium treated collagen is currently unknown. However, we hypothesize that collagen modifications including proteolytic degradation and exposure of epitopes and/or binding of collagen to bacterial components that together might activate THP-cells via redundant pathways might be responsible.

Fig. 4. T. forsythia MGO contributes to proinflammatory cytokine induction.

Cytokine levels in culture supernatants of THP-1 cells after challenge with bacterial spent medium (a) or collagen (10 and 20 µg/ml) exposed to wild-type (collagen + Tf43037) or mutant (collagen + TFM-1726) spent medium; collagen treated with TFB or MGO was used as control (b). (a) * P< 0.05; **, P<0.005, ***, P<0.001 (n=3). (b) *, P<0.01 TFB treated collagen; #, P<0.01 versus Tf43037 spent medium treated collagen.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified and confirmed BFO_1726 as the functional methylglyoxal synthase (MgsA) enzyme involved in the synthesis of methylglyoxal (MGO) in T. forsythia. Furthermore, we showed that MGO production in T. forsythia plays a role in inflammogenic AGE formation. This was based on the data showing that the spent medium from the wild-type strain compared to the MgsA-deficient mutant induced significantly increased proinflammatory cytokine secretion in monocytes. Furthermore, the spent medium form the wild-type strain alone promoted the formation of glycated collagen adducts. The MgsA enzyme catalyzes the formation of methylglyoxal from dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) by enolization reaction. It aids bacteria by disposing their excess load of DHAP which can accumulate due to increased sugar availability, and thus helps in alleviating sugar stress in bacteria. MGO is an electrophilic compound toxic to the bacterial cell and can covalently modify amino acid side chains in proteins to generate inflammatory adducts known as advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs). Here we demonstrated that MGO production by T. forsythia might present the bacterium with an increased ability to induce inflammation. Genome mining studies indicated that T. forsythia’s ‘red complex’ partners P. gingivalis and T. denticola do not possess orthologs of mgsA gene.

We showed that T. forsythia produced MGO was responsible for the formation of AGE adducts that further activated NF-κB pathway via RAGE receptor, and induced high amount of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α. T. forsythia MGO caused collagen AGEs, which in turn induced secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in monocytes. These findings align with previous reports on the role of MGO in collagen modification24,28. Pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α contribute to the pathologic bone loss in periodontal disease. IL-1β and TNF-α stimulate osteoclastogenesis largely through up-regulation of receptor activator for nuclear factor-κB (RANK) ligand35,36.

MGO produced by intestinal bacteria is reported as a potential toxic metabolite involved in many gut diseases, including functional constipation37. Moreover, microbiome of functionally constipated individuals show lower abundance of genes involved in MGO degradation as compared to healthy microbiome38. Together, these studies highlight MGO as toxic metabolite in gut diseases. The contribution of methylglyoxal remains largely undefined in pathogenesis of PD. The ability of T. forsythia to secrete copious amounts of MGO was first demonstrated by Maiden and co-workers14. Furthermore, increasing levels of MGO correlating with the infection levels of T. forsythia are reported in gingival exudates from severe periodontal lesions17,28. Moreover, MGO’s potential involvement in PD is supported from in vitro studies demonstrating that MGO can induce apoptosis in gingival fibroblasts and chemically alter collagen (collagen adducts) to activate TIMP-1 expression in fibroblasts17,28. Furthermore, MGO can modify human β-defensin peptides by reacting with Lys, Arg and Cys residues, thereby blocking their antimicrobial as well as chemotactic function39. MGO is a highly reactive host and bacterially produced molecule that can covalently modify the arginyl, lysyl and sulfhydryl residues of proteins, resulting in the crosslinking and modification of host proteins, which may lead to loss of protein integrity and function40–43. MGO modified proteins can also interact with specific cellular receptors to induce cellular stress responses including endocytosis, cytokine release and apoptosis. It has also been shown that MGO in the free form can trigger the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and cell adhesion molecules (P-selectin, E-selectin and ICAM-1) by activating various signaling pathways such as nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways in endothelial cells and leucocytes29–32. In addition to the toxic killing effect of MGO on the bacterial cell, MGO can also modify its virulence components such as fimbriae, flagella and other components44. Considering the inflammogenic and toxic potential of MGO, we predict that T. forsythia produced MGO may contribute to the pathogenesis of periodontitis via multiple and complex pathways. However, it remains to be seen whether T. forsythia has systems to detoxify self-produced MGO. Bacteria that produce MGO possess an array of detoxification pathways for methylglyoxal45.

In conclusion, we demonstrated the inflammogenic potential of T. forsythia MGO via the formation of immunogenic AGEs and triggering inflammatory signals in immune cells. We also speculate that MGO produced by T. forsythia might drive dysbiotic inflammation due to its potential toxicity on the resident oral flora.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by NIDCR award DE14749 (to AS), University at Buffalo Innovative Micro-Programs Accelerating Collaboration in Themes – IMPACT Grant (to ML), NIH award AR070179 (to DX), and Sunstar Buffalo Microbiome Center (RJG). RPS was supported by the NIDCR Training Program in Oral Sciences T32 DE023526.

Footnotes

Disclosures – R. Genco is a consultant for Sunstar, Inc., Colgate, and Cigna.

References

- 1.Lamont RJ, Hajishengallis G. Polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis in inflammatory disease. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21(3):172–183. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Tanner A, et al. Subgingival microbiota in healthy, well-maintained elder and periodontitis subjects. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25(5):346–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haraszthy VI, Zambon JJ, Trevisan M, Zeid M, Genco RJ. Identification of periodontal pathogens in atheromatous plaques. J Periodontol. 2000;71(10):1554–1560. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.10.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Genco R, Offenbacher S, Beck J. Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease: epidemiology and possible mechanisms. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133(Suppl):14S–22S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geismar K, Stoltze K, Sigurd B, Gyntelberg F, Holmstrup P. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease. J Periodontol. 2006;77(9):1547–1554. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koziel J, Mydel P, Potempa J. The link between periodontal disease and rheumatoid arthritis: an updated review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2014;16(3):408. doi: 10.1007/s11926-014-0408-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scher JU, Ubeda C, Equinda M, et al. Periodontal disease and the oral microbiota in new-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(10):3083–3094. doi: 10.1002/art.34539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Preshaw PM, Alba AL, Herrera D, et al. Periodontitis and diabetes: a two-way relationship. Diabetologia. 2012;55(1):21–31. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2342-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor JJ, Preshaw PM, Lalla E. A review of the evidence for pathogenic mechanisms that may link periodontitis and diabetes. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(Suppl 14):S113–134. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar PS. Oral microbiota and systemic disease. Anaerobe. 2013;24:90–93. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adler CJ, Dobney K, Weyrich LS, et al. Sequencing ancient calcified dental plaque shows changes in oral microbiota with dietary shifts of the Neolithic and Industrial revolutions. Nat Genet. 2013;45(4):450–455. doi: 10.1038/ng.2536. 455e451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ready D, D'Aiuto F, Spratt DA, Suvan J, Tonetti MS, Wilson M. Disease severity associated with presence in subgingival plaque of Porphyromonas gingivalis, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, and Tannerella forsythia, singly or in combination, as detected by nested multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(10):3380–3383. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01007-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma A. Virulence mechanisms of Tannerella forsythia. Periodontol 2000. 2010;54(1):106–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00332.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maiden MF, Pham C, Kashket S. Glucose toxicity effect and accumulation of methylglyoxal by the periodontal anaerobe Bacteroides forsythus. Anaerobe. 2004;10(1):27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baskaran S, Rajan DP, Balasubramanian KA. Formation of methylglyoxal by bacteria isolated from human faeces. J Med Microbiol. 1989;28(3):211–215. doi: 10.1099/00222615-28-3-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell AK, Matthews SB, Vassel N, et al. Bacterial metabolic 'toxins': a new mechanism for lactose and food intolerance, and irritable bowel syndrome. Toxicology. 2010;278(3):268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kashket S, Maiden MF, Haffajee AD, Kashket ER. Accumulation of methylglyoxal in the gingival crevicular fluid of chronic periodontitis patients. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30(4):364–367. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma A, Sojar HT, Glurich I, Honma K, Kuramitsu HK, Genco RJ. Cloning, expression, and sequencing of a cell surface antigen containing a leucine-rich repeat motif from Bacteroides forsythus ATCC 43037. Infect Immun. 1998;66(12):5703–5710. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5703-5710.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma A, Sojar HT, Glurich I, Honma K, Kuramitsu HK, Genco RJ. Cloning, expression, and sequencing of a cell surface antigen containing a leucine-rich repeat motif from Bacteroides forsythus ATCC 43037. Infection and immunity. 1998;66(12):5703–5710. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5703-5710.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honma K, Inagaki S, Okuda K, Kuramitsu HK, Sharma A. Role of a Tannerella forsythia exopolysaccharide synthesis operon in biofilm development. Microb Pathog. 2007;42(4):156–166. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fletcher HM, Schenkein HA, Morgan RM, Bailey KA, Berry CR, Macrina FL. Virulence of a Porphyromonas gingivalis W83 mutant defective in the prtH gene. Infect Immun. 1995;63(4):1521–1528. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1521-1528.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLellan AC, Phillips SA, Thornalley PJ. The assay of methylglyoxal in biological systems by derivatization with 1,2-diamino-4,5-dimethoxybenzene. Anal Biochem. 1992;206(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(05)80005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dobler D, Ahmed N, Song L, Eboigbodin KE, Thornalley PJ. Increased dicarbonyl metabolism in endothelial cells in hyperglycemia induces anoikis and impairs angiogenesis by RGD and GFOGER motif modification. Diabetes. 2006;55(7):1961–1969. doi: 10.2337/db05-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chong SA, Lee W, Arora PD, et al. Methylglyoxal inhibits the binding step of collagen phagocytosis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282(11):8510–8520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609859200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu D, Young JH, Krahn JM, et al. Stable RAGE-heparan sulfate complexes are essential for signal transduction. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8(7):1611–1620. doi: 10.1021/cb4001553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu D, Young J, Song D, Esko JD. Heparan sulfate is essential for high mobility group protein 1 (HMGB1) signaling by the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) J Biol Chem. 2011;286(48):41736–41744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.299685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freedberg WB, Kistler WS, Lin EC. Lethal synthesis of methylglyoxal by Escherichia coli during unregulated glycerol metabolism. J Bacteriol. 1971;108(1):137–144. doi: 10.1128/jb.108.1.137-144.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Retamal IN, Hernandez R, Gonzalez-Rivas C, et al. Methylglyoxal and methylglyoxal-modified collagen as inducers of cellular injury in gingival connective tissue cells. J Periodontal Res. 2016;51(6):812–821. doi: 10.1111/jre.12365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biswas S, Ray M, Misra S, Dutta DP, Ray S. Selective inhibition of mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis in human leukaemic leucocytes by methylglyoxal. Biochem J. 1997;323(Pt 2):343–348. doi: 10.1042/bj3230343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akhand AA, Hossain K, Mitsui H, et al. Glyoxal and methylglyoxal trigger distinct signals for map family kinases and caspase activation in human endothelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31(1):20–30. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00550-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams JL, Badger AM, Kumar S, Lee JC. p38 MAP kinase: molecular target for the inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Prog Med Chem. 2001;38:1–60. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6468(08)70091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamawaki H, Saito K, Okada M, Hara Y. Methylglyoxal mediates vascular inflammation via JNK and p38 in human endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295(6):C1510–1517. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00252.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Settem RP, El-Hassan AT, Honma K, Stafford GP, Sharma A. Fusobacterium nucleatum and Tannerella forsythia induce synergistic alveolar bone loss in a mouse periodontitis model. Infect Immun. 2012;80(7):2436–2443. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06276-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Settem RP, Honma K, Nakajima T, et al. A bacterial glycan core linked to surface (S)-layer proteins modulates host immunity through Th17 suppression. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6(2):415–426. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Devlin RD, Reddy SV, Savino R, Ciliberto G, Roodman GD. IL-6 mediates the effects of IL-1 or TNF, but not PTHrP or 1,25(OH)2D3, on osteoclast-like cell formation in normal human bone marrow cultures. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13(3):393–399. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wei S, Kitaura H, Zhou P, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL. IL-1 mediates TNF-induced osteoclastogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(2):282–290. doi: 10.1172/JCI23394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mancabelli L, Milani C, Lugli GA, et al. Unveiling the gut microbiota composition and functionality associated with constipation through metagenomic analyses. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):9879. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10663-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang S, Jiao T, Chen Y, Gao N, Zhang L, Jiang M. Methylglyoxal induces systemic symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. PloS one. 2014;9(8):e105307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kiselar JG, Wang X, Dubyak GR, et al. Modification of beta-Defensin-2 by Dicarbonyls Methylglyoxal and Glyoxal Inhibits Antibacterial and Chemotactic Function In Vitro. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0130533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagaraj RH, Shipanova IN, Faust FM. Protein cross-linking by the Maillard reaction. Isolation, characterization, and in vivo detection of a lysine-lysine cross-link derived from methylglyoxal. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(32):19338–19345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahmed MU, Brinkmann Frye E, Degenhardt TP, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW. N-epsilon-(carboxyethyl)lysine, a product of the chemical modification of proteins by methylglyoxal, increases with age in human lens proteins. Biochem J. 1997;324(Pt 2):565–570. doi: 10.1042/bj3240565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Booth AA, Khalifah RG, Todd P, Hudson BG. In vitro kinetic studies of formation of antigenic advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Novel inhibition of post-Amadori glycation pathways. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(9):5430–5437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oya T, Hattori N, Mizuno Y, et al. Methylglyoxal modification of protein. Chemical and immunochemical characterization of methylglyoxal-arginine adducts. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(26):18492–18502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rabie E, Serem JC, Oberholzer HM, Gaspar AR, Bester MJ. How methylglyoxal kills bacteria: An ultrastructural study. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2016;40(2):107–111. doi: 10.3109/01913123.2016.1154914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferguson GP, Totemeyer S, MacLean MJ, Booth IR. Methylglyoxal production in bacteria: suicide or survival? Arch Microbiol. 1998;170(4):209–218. doi: 10.1007/s002030050635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.