Abstract

We compared the prevalence of various medical and behavioral co-occurring conditions/symptoms between 4- and 8-year-olds with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) from five sites in the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network during the 2010 survey year, accounting for sociodemographic differences. Over 95% of children had at least one co-occurring condition/symptom. Overall, the prevalence was higher in 8- than 4-year-olds for 67% of co-occurring conditions/symptoms examined. Further, our data suggested that co-occurring conditions/symptoms increased or decreased the age at which children were first evaluated for ASD. Similarly, among the 8-year-olds, the prevalence of most co-occurring conditions/symptoms was higher in children with a previous ASD diagnosis documented in their records. These findings are informative for understanding and screening co-occurring conditions/symptoms in ASD.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, Autism, Prevalence, Co-occurring conditions, Comorbid conditions

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a group of neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by deficits in social communication and interaction and the presence of restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviors, interests, and activities (American Psychiatric Association 2013). In addition, affected individuals may have co-occurring conditions/symptoms. The most frequently reported are: intellectual disability (ID); Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD); developmental regression; behavioral, sleep, sensory processing, and gastrointestinal problems; and ASD-associated genetic conditions, such as Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome (Bauman 2010; Gurney et al. 2006; Kielinen et al. 2004; Krakowiak et al. 2008; Levy et al. 2010; Lundstrom et al. 2015; Simonoff et al. 2008; Supekar et al. 2017; Wiggins et al. 2009).

In 8-year-olds with ASD from the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network, Levy et al. (2010) reported that 83% had at least one co-occurring developmental diagnosis, 16% had at least one co-occurring neurologic diagnosis, and 10% at least one psychiatric diagnosis. Further, other studies have reported that co-occurring conditions/symptoms tend to cluster in the same individual (Boulet et al. 2009; Fulceri et al. 2016; Hirata et al. 2016; Levy et al. 2010; Lundstrom et al. 2015; Magnusdottir et al. 2016; Simonoff et al. 2008). Using the National Health Interview Survey data, Boulet et al. (2009) found that 96% of children with ASD had one or more co-occurring developmental disabilities. Likewise, Simonoff et al. (2008) found that 70% of children with ASD had at least one co-occurring condition/symptom and 41% had two or more co-occurring conditions/symptoms.

Co-occurring conditions/symptoms contribute to the heterogeneity in ASD phenotype and may influence its recognition. Some co-occurring conditions/symptoms can mask or modify the expression of the core ASD symptoms, which may result in later age of diagnosis or loss of a previous diagnosis (Blumberg et al. 2016; Close et al. 2012; Davidovitch et al. 2015; Jonsdottir et al. 2011; Levy et al. 2010; Mandell et al. 2007; Mazurek et al. 2014; Wiggins et al. 2012; Wu et al. 2016). For example, Davidovitch et al. (2015) found that children with language or cognitive deficits, or attention or motor problems were more likely to be diagnosed with ASD after the age of 6 years, even though they were initially evaluated at a younger age. A current or past developmental condition (e.g., developmental delay, hearing problem) or other disorders, such as anxiety or epilepsy, was associated with a loss of a previous ASD diagnosis (Close et al. 2012). Studies have documented sociodemographic differences in the prevalence of some co-occurring conditions. For example, Supekar et al. (2017) reported sex differences in ADHD and epilepsy in those with ASD. Likewise, Non-Hispanic White children were more likely to have a diagnosis of ADHD than children from other racial/ethnic groups (Coker et al. 2016).

Co-occurring conditions/symptoms increase the societal impact of ASD, since they often contribute to a higher level of impairment, increased need for services, including medications and emergency rooms visits for injuries, impacting the quality of life of children with ASD and their families (Gurney et al. 2006; Ianuzzi et al. 2015; Malow et al. 2016; Peacock et al. 2012; Posserud et al. 2018; Schieve et al. 2012; Sikora et al. 2012; Vohra et al. 2016).

Most past studies had methodological limitations, including (1) use of clinic-based samples, which may not be representative of those with ASD; (2) reliance on parental report for the diagnosis of ASD and co-occurring conditions/symptoms; (3) no adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics that may differ among children with ASD at different ages, and (4) assessment of a limited set of co-occurring conditions/symptoms. Further, while a few studies reported differences in the prevalence of co-occurring conditions/symptoms between age groups (Croen et al. 2015; Lever and Geurts 2016; Mannion and Leader 2016; Supekar et al. 2017), there is a need for large population-based studies. In this study, we compared the prevalence of various medical and behavioral co-occurring conditions/symptoms between 4- and 8-year-old children in a population-based sample, accounting for sociodemographic differences. Secondarily, we evaluated whether the presence of co-occurring conditions/symptoms affected the age at which children were first evaluated for ASD.

Methods

Study Design

This is a cross-sectional, secondary analysis of data from the ADDM Network surveillance system collected during the 2010 survey year. Data collection was done under the ADDM protocol, which was approved by the institutional review board at each ADDM site.

Data Source and Participants

Since 2000, the ADDM Network has been tracking the prevalence of ASD among 8-year-old children in selected areas of the United States (Yeargin-Allsopp et al. 2003). Surveillance among 4-year-old children was added in 2010 in a subset of sites to assess early identification of ASD. The ADDM Network is an active, multisite surveillance system for ASD and other developmental disabilities that use information from children’s health and education records to determine case classification. During the 2010 survey year, 11 sites conducted surveillance among 8-year-old children (born in 2002) and five of these sites (Arizona, Missouri, New Jersey, Utah, and Wisconsin) also conducted surveillance among 4-year-old children (born in 2006). This analysis includes only data from these five sites. Previous ADDM studies have shown that the reported ASD prevalence was consistently lower in sites with access to health records only versus sites with access to both health and education records, suggesting a potential under-ascertainment in the former group (Christensen et al. 2016; Soke et al. 2017). During the 2010 survey year, Arizona, New Jersey, and Utah had access to health and education records and were classified as “sites with more complete case ascertainment”, while Missouri and Wisconsin used health records only and were considered “sites with less complete case ascertainment” (Soke et al. 2017).

In all ADDM sites, case determination follows a standardized, validated, multi-step common approach, which is detailed in other publications (CDC 2016; Christensen et al. 2016; Soke et al. 2017; Yeargin-Allsopp et al. 2003). In brief, health records (all sites) and health and education records (some sites) of children, who (1) live in the ADDM catchment areas, (2) are 4 or 8-years old during the surveillance year, and (3) have international classification of diseases (ICD) and special education codes indicative of ASD or other developmental disabilities, are first screened. This screening consists of determining whether these records contain social deficits symptoms associated with ASD, a documented or suspected diagnosis of ASD by a qualified professional, eligibility for autism special education services, or presence of an autism test administered by a qualified professional. If any of these four above conditions are met, information from all available comprehensive developmental evaluations of the child from birth to age 4 or 8 years is abstracted verbatim, and for each child, evaluations from multiple sources are summarized into a single file. Expert clinicians at each site review the summarized abstraction file using criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders-IV-Edition-Text Revision [DSM-IV-TR] (APA 2000) to decide if the child meets the ADDM case classification for ASD. The DSM-IV-TR criteria were used instead of DSM-5 because children included in this study were evaluated prior to the revision of the ASD diagnostic criteria in 2013. In addition to determining whether a child meets the ASD criteria, ADDM expert clinicians review each child’s summary file to assess if there is documentation of any co-occurring condition/symptom in the child’s evaluations between birth to age 4 or 8 years. The documentation of these co-occurring conditions/symptoms by ADMM experts clinicians was based on a pre-specified list of co-occurring conditions/symptoms in ASD (see Supplemental Table 1 for the complete list). The ADDM final dataset is linked to area census data and birth certificate data, if available.

Key Variables

The outcome of interest is the presence of one or more documented co-occurring conditions/symptoms in the child summary record. We assessed 18 most prevalent co-occurring conditions/symptoms among those listed in Supplemental Table 1. These co-occurring conditions/symptoms were coded by the reviewer as present or absent. Since we found differences between 4-year and 8-year-old children on sociodemographic characteristics and because most co-occurring conditions varied with child’s sex and race/ethnicity, maternal education, and study site (data not shown), these variables were included as covariates. In a subset of children with a documented previous ASD diagnosis from a community provider in their records, we evaluated the age at the first evaluation confirming a diagnosis of ASD.

Analytical Strategy

We used log-binomial regression to compare the prevalence of co-occurring conditions/symptoms between 4- and 8-year-old children. We first calculated the unadjusted prevalence ratio (PR) for each co-occurring condition/symptom individually between 4- and 8-year-old children using the 4-year group as the reference in all five sites. In the next step, we calculated the adjusted PR accounting for the four above variables. In a sub-group analysis, we calculated PRs in the three sites with “more complete case ascertainment”, and in the two sites with less complete case ascertainment. Because of small cell numbers in some co-occurring condition/symptoms, we did not report PRs when cells had less than five children. We also compared the number of co-occurring conditions documented for each child between the two age groups. Among children with a documented previous diagnosis in their records, we compared the mean age (months) at which children were first evaluated for ASD between children with and without a specific co-occurring condition/symptom in each age group. As a post-hoc analysis, in 8-year-olds, we compared the prevalence of each co-occurring condition/symptom between children with a previous ASD diagnosis in their records and those without it to assess whether the presence of a co-occurring condition/symptom affected ASD diagnosis. We limited this sub-analysis to 8-year-olds since we found that the prevalence of a previous ASD diagnosis and of most co-occurring conditions/symptoms were lower in 4-year-olds versus 8-year-olds. Therefore, findings in 4-year-olds may be uninformative.

Results

This study included 4-year-olds (n = 783) and 8-year-olds (n = 1091). Sociodemographic characteristics of the two age groups are presented in Table 1. The ratio male to female tended to be higher in 8- versus 4-year-olds and there were more Non-Hispanic White children in the older age group compared to the younger age group. Unadjusted and adjusted PRs comparing the two age groups in all five sites are presented in Table 2. The prevalence was higher in 8-year-olds compared to 4- year-olds for 12 of the 18 (67%) co-occurring conditions/symptoms. However, these differences were statistically significant for only eight conditions/symptoms (ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, anxiety, aggression, language disorder, sleep abnormalities, motor disability, and mood problems). For the remaining six co-occurring conditions/symptoms examined, the prevalence was lower in 8-year-olds compared to 4-year-olds, but none of these differences were significant. The subgroup analysis in sites with more complete and less complete case ascertainment is presented in Table 3. Though most findings were comparable in the two subgroups of sites, some differences were noted. Significant differences in cognitive and motor developmental disabilities, and language disorder were only observed in sites with access to both health and education records. Conversely, a significant difference in the prevalence of temper tantrums in 8-year versus 4-year-olds was noted in the two sites with access to health records only.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 4- and 8-year-old children with autism spectrum disorder in the Early ADDM Network during the 2010 surveillance year

| Variable | 4-year-olds (n=783) |

8-year-olds (n=1091) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 173 (22.09) | 207 (18.97) | |

| Male | 610 (77.91) | 884 (81.03) | .10 |

| Race | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 374 (47.76) | 594 (54.45) | |

| Others | 381 (48.66) | 446 (40.88) | |

| Missing | 28 (3.58) | 51 (4.67) | 0.003 |

| Maternal education | 0.09 | ||

| Post high school education | 381 (48.66) | 507 (46.47) | |

| High school diploma or less | 256 (32.69) | 335 (30.71) | |

| Missing | 146 (18.65) | 249 (22.82) | |

| Previous ASD diagnosis in the records | |||

| Yes | 513 (65.52) | 834 (76.44) | |

| No | 270 (34.48) | 257 (23.56) | <0.0001 |

| Specific sites | |||

| Arizona | 123 (15.71) | 155 (14.21) | |

| Missouri | 103 (13.15) | 207 (18.97) | |

| New Jersey | 352 (44.96) | 404 (37.03) | |

| Utah | 132 (16.86) | 190 (17.42) | |

| Wisconsin | 73 (9.32) | 135 (12.37) | .0003 |

Bold values were significant at the conventional P-value of 0.05

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted prevalence ratios of medical and behavioral co-occurring conditions between 4- and 8-year-old children with autism spectrum disorder in the Early ADDM Network during the 2010 surveillance year

| Co-occurring condition/symptom | 4-year-olds (n = 783) | 8-year-olds (n = 1091) | Unadjusted prevalence ratio and 95% CI 8 versus 4 years | Adjusteda prevalence ratio and 95% CI 8 versus 4 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental disability-cognitive | ||||

| Yes | 131 (16.73) | 159 (14.57) | 0.87 (0.70, 1.08) | 0.83 (0.67, 1.05) |

| No | 652 (83.27) | 932 (85.43) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Congenital conditionsb | ||||

| Yes | 84 (10.73) | 145 (13.30) | 1.24 (0.96, 1.59) | 0.93 (0.75, 1.16) |

| No | 699 (89.27) | 946 (86.70) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Self-injurious behaviors | ||||

| Yes | 192 (24.52) | 273 (25.02) | 1.02 (0.87, 1.20) | 0.94 (0.79, 1.12) |

| No | 591 (75.48) | 818 (74.98) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sensory integration disorder | ||||

| Yes | 63 (8.05) | 95 (8.70) | 1.08 (0.80, 1.47) | 0.96 (0.68, 1.34) |

| No | 720 (91.95) | 996 (91.30) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Developmental regression | ||||

| Yes | 154 (19.67) | 211 (19.34) | 0.98 (0.82, 1.18) | 0.98 (0.80, 1.20) |

| No | 629 (80.33) | 880 (80.66) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Epilepsy/seizure disorder | ||||

| Yes | 22 (2.81) | 33 (3.02) | 1.08 (0.63, 1.83) | 0.99 (0.54, 1.84) |

| No | 761 (97.19) | 1058 (96.98) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ADHD | ||||

| Yes | 43 (5.49) | 306 (26.05) | 5.11 (3.76, 6.93) | 4.78 (3.40, 6.73) |

| No | 740 (94.51) | 785 (71.95) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | ||||

| Yes | 7 (0.89) | 44 (4.03) | 4.51 (2.04, 9.96) | 4.13 (1.75, 9.75) |

| No | 776 (99.11) | 1047 (95.97) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Anxiety | ||||

| Yes | 37 (4.73) | 122 (11.18) | 2.37 (1.66, 3.38) | 2.28 (1.57, 3.39) |

| No | 746 (95.27) | 969 (88.82) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Aggression | ||||

| Yes | 306 (39.08) | 592 (54.26) | 1.39 (1.25, 1.54) | 1.39 (1.24, 1.56) |

| No | 477 (60.92) | 499 (45.74) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Language disorder | ||||

| Yes | 204 (26.05) | 380 (34.83) | 1.34 (1.16, 1.54) | 1.39 (1.19, 1.62) |

| No | 579 (73.95) | 711 (65.17) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sleep abnormalities | ||||

| Yes | 211 (26.95) | 405 (37.12) | 1.38 (1.20, 1.58) | 1.34 (1.15, 1.56) |

| No | 572 (73.05) | 686 (62.88) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Developmental disability-motor | ||||

| Yes | 169 (21.58) | 293 (26.86) | 1.24 (1.05, 1.47) | 1.30 (1.08, 1.56) |

| No | 614 (78.42) | 798 (73.14) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Genetic conditionsc | ||||

| Yes | 4 (0.51) | 7 (0.64) | 1.26 (0.37, 4.27) | 1.30 (0.38, 4.43) |

| No | 779 (99.49) | 1084 (99.36) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mood disorder | ||||

| Yes | 438 (56.00) | 816 (74.80) | 1.33 (1.24, 1.43) | 1.25 (1.16, 1.35) |

| No | 345 (44.00) | 275 (25.20) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Developmental disability-adaptive | ||||

| Yes | 159 (20.31) | 227 (20.81) | 1.02 (0.86, 1.23) | 1.13 (0.93, 1.36) |

| No | 624 (79.69) | 864 (79.19) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Abnormalities in eating, drinking | ||||

| Yes | 403 (51.47) | 619 (56.74) | 1.10 (1.01, 1.20) | 1.06 (0.97, 1.17) |

| No | 380 (48.53) | 472 (43.26) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Temper tantrums | ||||

| Yes | 428 (54.66) | 603 (55.27) | 1.01 (0.93, 1.10) | 1.03 (0.94, 1.13) |

| No | 355 (45.34) | 488 (44.73) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Bold values were significant at the conventional P-value of 0.05

CI confidence interval, ADHD attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Adjusted for child sex, child race/ethnicity, maternal education, and study site

Congenital conditions include Cerebral palsy, encephalopathy, vision impairment and hearing loss

Genetic conditions include Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome, Tuberous sclerosis

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted prevalence ratios of medical and behavioral co-occurring conditions between 4- and 8-year-old children with autism spectrum disorder in the Early ADDM Network during the 2010 surveillance year depending on the type of records assessed by the sites

| Co-occurring condition/symptom | Prevalence in 4–year-olds (n=607) | Prevalence in 8-year-olds (n=749) | Prevalence ratios between 8-year and 4-year-olds in the three sites with access to both health and education records

|

Prevalence in 4-year-olds (n=176) | Prevalence in 8-year-olds (n=342) | Prevalence ratios between 8-year and 4-year-olds in the two sites with access to health records only

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted estimates and 95% CI | Adjusteda estimates and 95% CI | Unadjusted estimates and 95% CI | Adjusteda estimates and 95% CI | |||||

| Developmental Disability-Cognitive | ||||||||

| Yes | 122 (20.10) | 117 (15.62) | 0.78 (0.62, 0.98) | 0.73 (0.57, 0.95) | 9 (5.11) | 42 (12.28) | 2.40 (1.20, 4.82) | 1.95 (0.95, 4.00) |

| No | 485 (79.90) | 632 (84.38) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 167 (94.89) | 300 (87.72) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Congenital conditionsb | ||||||||

| Yes | 23 (3.79) | 46 (6.14) | 1.62 (0.99, 2.64) | 1.56 (0.90, 2.69) | 61 (34.66) | 99 (28.95) | 0.84 (0.64, 1.08) | 0.77 (0.59, 1.02) |

| No | 584 (96.21) | 703 (93.86) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 115 (65.34) | 243 (71.05) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Self-injurious behaviors | ||||||||

| Yes | 150 (24.71) | 183 (24.43) | 0.99 (0.82, 1.19) | 0.90 (0.73, 1.11) | 42 (23.86) | 90 (26.32) | 1.10 (0.80, 1.52) | 1.02 (0.72, 1.44) |

| No | 457 (75.29) | 566 (75.57) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 134 (76.14) | 252 (73.68) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sensory integration disorder | ||||||||

| Yes | 55 (9.06) | 75 (10.01) | 1.11 (0.79, 1.54) | 0.91 (0.63, 1.32) | 8 (4.55) | 20 (5.85) | 1.29 (0.58, 2.86) | 1.26 (0.49, 3.22) |

| No | 552 (90.94) | 674 (89.99) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 168 (95.45) | 322 (94.15) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Developmental regression | ||||||||

| Yes | 116 (19.11) | 133 (17.76) | 0.93 (0.74, 1.16) | 0.98 (0.77, 1.26) | 38 (21.59) | 78 (22.81) | 1.06 (0.75, 1.49) | 1.02 (0.69, 1.49) |

| No | 491 (80.89) | 616 (82.24) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 138 (78.41) | 264 (77.19) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Epilepsy/seizure disorder | ||||||||

| Yes | 15 (2.47) | 19 (2.54) | 1.03 (0.53, 2.00) | 0.85 (0.39, 1.89) | 7 (3.98) | 14 (4.09) | 1.03 (0.42, 2.50) | 1.46 (0.53, 4.08) |

| No | 592 (97.53) | 730 (97.46) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 169 (96.02) | 328 (95.91) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ADHD | ||||||||

| Yes | 32 (5.27) | 196 (26.17) | 4.96 (3.47, 7.10) | 4.32 (2.94, 6.37) | 11 (6.25) | 110 (32.16) | 5.15 (2.84, 9.31) | 6.46 (3.06, 13.62) |

| No | 575 (94.73) | 553 (73.83) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 165 (93.75) | 232 (67.84) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | ||||||||

| Yes | 6 (0.99) | 32 (4.27) | 4.32 (1.82, 10.27) | 3.70 (1.43, 9.60) | 1 (0.57) | 12 (3.51) | – | – |

| No | 601 (99.01) | 717 (95.73) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 175 (99.43) | 330 (67.84) | – | – |

| Anxiety | ||||||||

| Yes | 34 (5.60) | 78 (10.41) | 1.86 (1.26, 2.74) | 1.66 (1.09, 2.53) | 3 (1.70) | 44 (12.87) | – | – |

| No | 573 (94.40) | 671 (89.59) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 173 (98.30) | 298 (87.13) | – | – |

| Aggression | ||||||||

| Yes | 249 (41.02) | 408 (54.47) | 1.33 (1.18, 1.49) | 1.32 (1.15, 1.50) | 57 (32.39) | 184 (53.80) | 1.66 (1.31, 2.10) | 1.74 (1.34, 2.27) |

| No | 358 (58.98) | 341 (45.53) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 119 (67.61) | 158 (46.20) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Language disorder | ||||||||

| Yes | 171 (28.17) | 314 (41.92) | 1.49 (1.28, 1.73) | 1.49 (1.26, 1.76) | 33 (18.75) | 66 (19.30) | 1.03 (0.71, 1.50) | 0.96 (0.62, 1.48) |

| No | 436 (71.83) | 435 (58.08) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 143 (81.25) | 276 (80.70) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sleep abnormalities | ||||||||

| Yes | 150 (24.71) | 254 (33.91) | 1.37 (1.16, 1.63) | 1.35 (1.11, 3.12) | 61 (34.66) | 151 (44.15) | 1.27 (1.01, 1.61) | 1.32 (1.01, 1.73) |

| No | 457 (75.29) | 495 (66.09) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 115 (65.34) | 191 (55.85) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Developmental disability-motor | ||||||||

| Yes | 143 (23.56) | 221 (29.51) | 1.25 (1.04, 1.50) | 1.27 (1.04, 1.56) | 26 (14.77) | 72 (21.05) | 1.43 (0.95, 2.15) | 1.42 (0.88, 2.27) |

| No | 464 (76.44) | 528 (70.49) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 150 (85.23) | 270 (78.95) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Genetic conditionsc | ||||||||

| Yes | 3 (0.49) | 3 (0.40) | – | – | 1 (0.57) | 4 (1.17) | – | – |

| No | 604 (99.51) | 746 (99.60) | – | – | 175 (99.43) | 338 (98.83) | – | – |

| Mood disorder | ||||||||

| Yes | 341 (56.18) | 561 (74.90) | 1.33 (1.23, 1.45) | 1.29 (1.18, 1.41) | 97 (55.11) | 255 (74.56) | 1.35 (1.17, 1.57) | 1.30 (1.11, 1.51) |

| No | 266 (43.82) | 188 (25.10) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 79 (44.89) | 87 (25.44) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Developmental disability-adaptive | ||||||||

| Yes | 141 (23.23) | 181 (24.17) | 1.04 (0.86, 1.26) | 1.09 (0.88, 1.35) | 18 (10.23) | 46 (13.45) | 1.32 (0.79, 2.20) | 1.32 (0.75, 2.35) |

| No | 466 (76.77) | 568 (75.83) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 158 (89.77) | 296 (86.55) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Abnormalities in eating, drinking | ||||||||

| Yes | 290 (47.78) | 405 (54.07) | 1.13 (1.02, 1.26) | 1.09 (0.97, 1.23) | 113 (64.20) | 214 (62.57) | 0.97 (0.85, 1.12) | 1.02 (0.88, 1.19) |

| No | 317 (52.22) | 344 (45.93) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 63 (35.80) | 128 (37.43) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Temper tantrums | ||||||||

| Yes | 362 (59.64) | 432 (57.68) | 0.97 (0.88, 1.06) | 0.97 (0.88, 1.07) | 66 (37.50) | 171 (50.0) | 1.33 (1.07, 1.66) | 1.39 (1.08, 1.78) |

| No | 245 (40.36) | 317 (42.32) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 110 (62.50) | 171 (50.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Bold values were significant at the conventional P-value of 0.05

CI confidence interval, ADHD attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Adjusted for child sex, child race/ethnicity, maternal education, and study site

Congenital conditions include Cerebral palsy, encephalopathy, vision impairment and hearing loss

Genetic conditions include Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome, Tuberous sclerosis

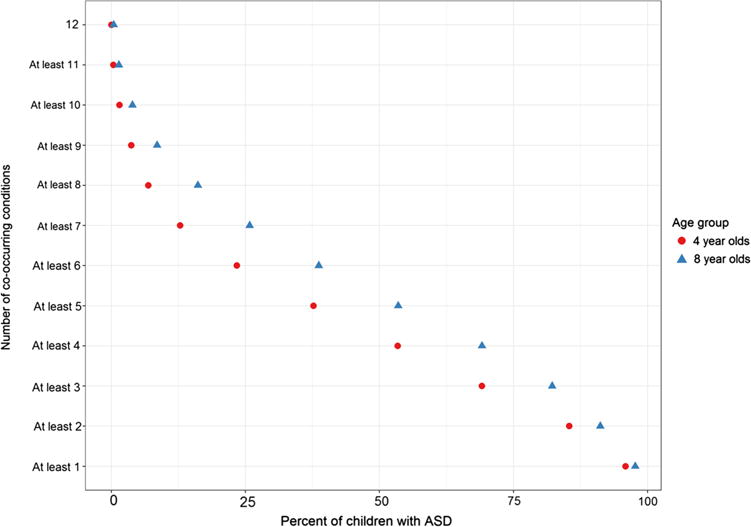

The mean number of co-occurring conditions/symptoms was 4.9 per child among 8-year-olds and 3.8 per child among 4-year-olds (data not shown). While nearly all 8- and 4-year old children had at least one co-occurring condition/symptom (98% and 96%, respectively), 8-year-old children had more conditions/symptoms recognized than 4-year-old children (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Proportion of children with co-occurring conditions in 4 and 8-year-old children with autism spectrum disorder in the Early ADDM Network during the 2010 survey year

For example, 69% and 53% of 8-year-olds and 4-year-olds, respectively, had four or more co-occurring conditions/symptoms; 26% and 13% of 8-year-olds and 4-year-olds, respectively, had seven or more co-occurring conditions/symptoms.

The comparisons of mean age at first evaluation confirming ASD diagnosis between those with and without a specific documented co-occurring condition/symptom in each age group are presented in Table 4. For some conditions/symptoms (e.g., developmental regression, cognitive disability, self-injurious behaviors, temper tantrums), both the unadjusted and adjusted mean age difference were negative i.e., children with these co-occurring conditions/symptoms were first evaluated for ASD at a younger age compared to children who did not have them. Conversely, for other co-occurring conditions/symptoms (e.g., ADHD, anxiety, oppositional defiant disorder, aggressive behaviors), the mean age difference was positive, i.e., those with these conditions were first evaluated for ASD at an older age compared to those without these conditions. Significant differences in the age at first evaluation were commonly found in 8- year versus 4-year-olds. Among 8-year-olds, the prevalence of 14 of 18 (78%) co-occurring conditions examined was higher in children with a previous diagnosis of ASD documented in their records versus those without it (Table 5).

Table 4.

Comparison of the mean age at the first evaluation confirming the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in months between children with and without a specific co-occurring condition in the Early ADDM Network during the 2010 surveillance year

| Co-occurring condition/symptom | Unadjusted mean difference and 95% CI in 4-year-olds | Adjusteda mean difference and 95% CI in 4-year-olds | Unadjusted mean difference and 95% CI in 8-year-olds | Adjusteda mean difference and 95% CI in 8 year-olds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental regression | − 3.8 (− 5.8, − 1.8) | − 3.9 (− 6.1, − 1.8) | − 14.4 (− 17.3, − 11.4) | − 13.9 (− 17.6, − 10.2) |

| Developmental disability-adaptive | − 2.5 (− 4.8, − 0.3) | − 2.1 (− 4.7, 0.5) | − 8.0 (− 11.1, − 4.8) | − 6.7 (− 11.0, − 2.3) |

| Abnormalities in eating, drinking | − 0.4 (− 2.2, 1.4) | − 0.6 (− 2.5, 1.4) | − 8.0 (− 11.1, − 5.0) | − 8.2 (− 11.7, − 4.7) |

| Developmental disability-cognitive | − 1.5 (− 3.9, 1.0) | − 1.9 (− 4.7, 0.8) | − 5.6 (− 9.7, − 1.6) | − 5.8 (− 10.4, − 1.1) |

| Temper tantrums | − 0.9 (− 2.7, 0.8) | − 1.0 (− 3.0, 0.9) | − 5.6 (− 8.7, − 2.6) | − 6.5 (− 9.8, − 3.1) |

| Developmental disability-motor | − 1.2 (− 3.3, 0.9) | − 1.6 (− 3.9, 0.8) | − 5.5 (− 8.7, − 2.4) | − 5.0 (− 8.7, − 1.2) |

| Congenital conditionsb | − 0.4 (− 2.9, 2.4) | 0.5 (− 2.8, 3.9) | − 4.1 (− 8.3, 0.2) | − 4.9 (− 10.3, 0.4) |

| Self-injurious behaviors | − 0.3 (− 2.3, 1.6) | − 0.9 (− 3.1, 1.2) | − 3.6 (− 6.9, − 0.3) | − 4.9 (− 8.6, − 1.1) |

| Sensory integration disorder | − 2.3 (− 5.2, 0.6) | − 1.7 (− 4.9, 1.4) | − 1.1 (− 6.0, 3.7) | − 2.7 (− 8.5, 3.1) |

| Epilepsy/seizure disorder | − 2.9 (− 8.8, 2.9) | − 3.6 (− 10.0, 2.9) | − 2.2 (− 10.1, 5.6) | − 3.5 (− 12.6, 5.6) |

| Language disorder | − 0.4 (− 2.2, 1.4) | 0.7 (− 1.5, 2.8) | − 2.2 (− 5.2, 0.8) | − 2.2 (− 5.9, 1.4) |

| ADHD | 0.7 (− 3.1, 4.4) | − 0.3 (− 4.4, 3.8) | 12.3 (8.8, 15.7) | 11.3 (7.7, 15.0) |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 5.5 (− 5.6, 16.6) | 5.7 (− 5.2, 16.7) | 9.9 (2.5, 17.4) | 10.5 (1.8, 19.1) |

| Anxiety | 3.9 (0.2, 9.7) | 3.6 (− 1.1, 8.2) | 6.8 (1.6, 12.0) | 6.9 (1.8, 12.0) |

| Genetic conditionsc | 2.0 (− 7.6, 11.7) | 2.2 (− 7.5, 11.9) | 12.5 (− 8.3, 33.3) | 14.5 (− 5.9, 34.8) |

| Mood disorder | 0.9 (− 0.9, 2.6) | 0.9 (− 1.1, 2.9) | 1.1 (− 2.3, 4.5) | 0.6 (− 3.4, 4.5) |

| Aggressive behaviors | 0.9 (− 0.9, 2.7) | 0.4 (− 1.6, 2.4) | 1.6 (− 1.4, 4.6) | 1.6 (− 1.8, 5.0) |

| Sleep abnormalities | − 1.3 (− 3.3, 0.6) | − 1.9 (− 4.1, 0.3) | − 0.4 (− 3.4, 2.6) | − 0.10 (− 4.5, 2.5) |

Bold values were significant at the conventional P-value of 0.05

CI confidence interval, ADHD attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Adjusted for child sex, child race/ethnicity, maternal education, and study site

Congenital conditions include Cerebral Palsy, encephalopathy, vision impairment and hearing loss

Genetic conditions include Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome, Tuberous sclerosis

Table 5.

Prevalence of medical and behavioral co-occurring conditions in 8- years olds in Early ADDM Network among children with and without a previous diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder during the 2010 survey year

| Co-occurring condition/symptom | Prevalence among children with a previous ASD diagnosis in the records (n=834) | Prevalence among children without a previous ASD diagnosis in the records (n=257) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental disability-cognitive | |||

| Yes | 130 (15.6) | 29 (11.3) | |

| No | 704 (84.4) | 228 (88.7) | 0.08 |

| Congenital conditionsa | |||

| Yes | 116 (13.9) | 29 (11.3) | 0.28 |

| No | 718 (86.1) | 228 (88.7) | |

| Self-injurious behaviors | |||

| Yes | 228 (27.3) | 45 (17.5) | |

| No | 606 (72.7) | 212 (82.5) | 0.002 |

| Sensory integration disorder | |||

| Yes | 84 (10.1) | 11 (4.3) | 0.004 |

| No | 750 (89.9) | 246 (95.7) | |

| Developmental regression | |||

| Yes | 192 (23.0) | 19 (7.4) | |

| No | 642 (77.0) | 238 (92.6) | <.0001 |

| Epilepsy/seizure disorder | |||

| Yes | 30 (3.6) | 3 (1.2) | |

| No | 804 (96.4) | 254 (98.8) | 0.05 |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | |||

| Yes | 227 (27.2) | 79 (30.7) | |

| No | 607 (72.8) | 178 (69.3) | 0.27 |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | |||

| Yes | 33 (4.0) | 11 (4.3) | |

| No | 801 (96.0) | 246 (95.7) | 0.82 |

| Anxiety | |||

| Yes | 100 (12.0) | 22 (8.6) | 0.13 |

| No | 734 (88.0) | 235 (91.4) | |

| Aggression | |||

| Yes | 462 (55.40) | 130 (50.6) | |

| No | 372 (44.60) | 127 (55.40) | 0.18 |

| Language disorder | |||

| Yes | 296 (35.5) | 84 (32.7) | |

| No | 538 (64.5) | 173 (67.3) | 0.41 |

| Sleep abnormalities | |||

| Yes | 339 (40.7) | 66 (25.7) | |

| No | 495 (59.3) | 191 (74.3) | <0.0001 |

| Developmental disabilities-motor | |||

| Yes | 218 (26.1) | 75 (29.2) | 0.34 |

| No | 616 (73.9) | 182 (70.8) | |

| Genetic conditionsb | |||

| Yes | 4 (0.5) | 3 (1.2) | |

| No | 830 (99.5) | 254 (98.8) | 0.23 |

| Mood disorder | |||

| Yes | 629 (75.4) | 187 (72.8) | |

| No | 205 (24.6) | 70 (27.2) | 0.39 |

| Developmental disabilities-adaptive | |||

| Yes | 167 (20.0) | 60 (23.4) | |

| No | 667 (80.0) | 197 (76.6) | 0.25 |

| Anomalies in eating, drinking | |||

| Yes | 509 (61.0) | 110 (42.8) | < 0.0001 |

| No | 325 (39.0) | 147 (57.2) | |

| Temper tantrums | |||

| Yes | 471 (56.5) | 132 (51.4) | 0.15 |

| No | 363 (43.5) | 125 (48.6) |

Bold values were significant at the conventional P-value of 0.05

ASD autism spectrum disorder

Congenital conditions include Cerebral Palsy, encephalopathy, vision impairment and hearing loss

Genetic conditions include Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome, Tuberous sclerosis

Discussion

We compared the prevalence of various medical and behavioral conditions/symptoms between 4- and 8-year-old children with ASD. Though co-occurring conditions/symptoms were documented in both age groups, the prevalence of most of them was higher in children in the older age group and those in the older group had more co-occurring conditions/symptoms. Further, for the majority of co-occurring conditions/symptoms, we found that the age at which children were evaluated for a possible ASD diagnosis increased or decreased when a co-occurring condition/symptom was documented, suggesting a possible association between co-occurring condition/symptoms and the age at first evaluation for ASD. Likewise, among 8-year-olds, the prevalence of most co-occurring conditions/symptoms was higher in those with a previous diagnosis of ASD than those without it.

In line with other studies (Gurney et al. 2006; Levy et al. 2010; Lundstrom et al. 2015; Nicholas et al. 2009; Simonoff et al. 2008; Supekar et al. 2017; Wiggins et al. 2015), we documented a high prevalence of co-occurring conditions/symptoms in those with ASD. As indicated by others (e.g., Levy et al. 2010; Lundstrom et al. 2015) and confirmed in our study, only a small proportion of children with ASD did not have any co-occurring condition/symptom. While the reasons behind this high prevalence are still unclear, their presence contributes to the ASD phenotype heterogeneity, which is a potential barrier to a timely diagnosis of ASD and a challenge for studying ASD etiology because of difficulties in defining a single early ASD behavioral marker (Georgiades et al. 2013; Waterhouse et al. 2016). Further, like others (Levy et al. 2010; Lundstrom et al. 2015; Simonoff et al. 2008; Wiggins et al. 2015), we confirmed the clustering of co-occurring conditions in the same child. We found that more than 95% of children with ASD, independent of their age group, had at least one co-occurring condition/symptom identified in their records. However, the proportion found in our study was higher compared to some of these studies (Levy et al. 2010; Simonoff et al. 2008; Wiggins et al. 2015). This may be due to a number of reasons, including, the type and number of co-occurring conditions/symptoms assessed and whether some of these co-occurring conditions/symptoms were combined in larger categories. Further, since the ADDM Network uses all available information from multiple sources from birth to the age of ascertainment, this may also explain the low proportion reported in studies that used only one data source (e.g., parental report) and included only a few evaluations. Because of the clustering of co-occurring condition/symptom reported in our study, this finding suggests, and as reported by others (Carbone et al. 2010; Kogan et al. 2008), that children with ASD may benefit from receiving services in a comprehensive system of care (i.e., medical home).

Similar to the study by Cummings et al. (2016), we found a higher prevalence for most conditions examined in the 8-year-old group compared to the 4-year-old group. A number of reasons, including developmental maturation with age, similarities between some of these co-occurring conditions/symptoms and the core symptoms of ASD in young children impeding their recognition, and fewer opportunities for evaluation by clinicians in 4-year-olds (specifically because they are not at school yet) may contribute to the observed differences (Christensen et al. 2016). Since co-occurring conditions/symptoms were still documented even in the younger age group (Hartley et al. 2008; Nicholas et al. 2009; Salazar et al. 2015; Wiggins et al. 2015), this has implications for the clinical assessment and management of children with ASD. As others have suggested and confirmed in our data, clinicians may consider screening for co-occurring conditions/symptoms in those with ASD, so the most appropriate interventions are identified and provided. We found a few differences on some co-occurring conditions between ADDM sites based on whether they had access to education records. Our findings suggest that having access to education records improved documentation of conditions such as cognitive and motor disabilities, and language disorder, which are often first identified in schools rather than in the health care system. Therefore, as reported by others on documenting the core ASD symptoms (Christensen et al. 2016), our findings suggest that access to education records is important in documenting the presence of some co-occurring conditions/symptoms. Though a significant difference in temper tantrums was observed in sites with health records, the prevalence at both ages were lower compared to sites with access to education records. On the other hand, these differences between sites may also be due to differences in providers practices, state specific health and education reporting requirements.

Among 8-years-olds, most co-occurring conditions influenced both the age at which children were first evaluated for a diagnosis of ASD and whether the child had a previous diagnosis of ASD documented in their records. However, different co-occurring conditions/symptoms might influence the age at first evaluation for ASD in opposing directions (i.e., increasing or decreasing the age). An early recognized co-occurring condition/symptom (e.g., developmental regression, self-injurious behaviors, and cognitive developmental delay) might result in earlier recognition of ASD, if the child receives an early comprehensive developmental assessment triggered by the co-occurring condition/symptom. For example, Jonsdottir et al. (2011) reported that children with ASD and co-occurring ID or developmental regression were more likely to be diagnosed before the age of 6 years than children without these conditions. Additionally, some co-occurring conditions/symptoms might impact severity of ASD symptoms, which again could trigger an earlier developmental assessment. Aldinger et al. (2015) found that co-occurring gastro-intestinal, sleep problems, and epilepsy increased the severity of core ASD symptoms. Likewise, our data also showed that children with developmental regression were more likely to have a previous diagnosis of ASD in their records than children without it. Conversely, symptoms of other co-occurring conditions (e.g., ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, aggression) might “mask” core ASD behaviors resulting in later identification of ASD. Similar to our findings, Frenette et al. (2011) reported that in children with a diagnosis of ADHD, attention and hyperactivity symptoms masked core ASD symptoms and could explain why they were diagnosed 1.29 years later than those without ADHD. Further, Davidovitch et al. (2015) reported that almost half of children later diagnosed with ASD were initially diagnosed with ADHD features and behaviors problems. The potential “masking effect” of ADHD symptoms on the diagnosis of ASD may lead clinicians to consider primarily a diagnosis of ADHD instead of ASD. This was also confirmed in our study since the prevalence of ADHD was lower in children with a previous ASD diagnosis compared to those without a previous diagnosis. Before the publication of the current DSM-5, ASD and ADHD were mutually exclusive diagnoses.

This study is the first to compare the prevalence of a large and diverse group of co-occurring conditions/symptoms between two different age groups of children with ASD using a large population-based sample, accounting for differences between the two age groups. Unlike Nicholas et al. (2009), we compared children from the same surveillance year, whose records were evaluated by the same clinicians, thus, reducing the effect of inter-reviewer variability. Further, this study included children with symptoms of ASD who did not have yet a diagnosis of ASD from the community. These children are not included in studies that use clinical samples, since a confirmed diagnosis of ASD is required. Nevertheless, this study had a few limitations. The various co-occurring conditions/symptoms examined were documented in the available child records. It is possible that we missed co-occurring conditions/symptoms for children whose records were not identified or unavailable. This may be important in the 4-year-old group, since they may not be receiving school services yet, therefore, health records constitute the only source of information. Co-occurring conditions/symptoms identified during early evaluations may not be confirmed in later evaluations in some children and we could have missed this information if these later evaluations were not available. This could have resulted in an overestimation of the prevalence of co-occurring conditions/symptoms in our study. However, our prevalence estimates were within the range of those reported in past studies. This analysis is cross-sectional at two age points and do not allow for a longitudinal assessment of co-occurring conditions/symptoms and also fails to account for between subject variability. Though our findings are from a population-based sample, they may have limited external validity, since these analyses included data from five sites not chosen to be a representative sample of children with ASD in the United States. While the age at which children were evaluated for a diagnosis of ASD was affected by the presence of a co-occurring condition/symptom, other factors that influence access to services, including family income, health insurance may also have contributed to this finding. Further, since some conditions may have not been identified yet by age 4, data from this age group may be limited to assess how co-occurring conditions might influence ASD evaluation or a previous diagnosis of ASD. The sub-analysis of sites based on records accessed had low power because of small cell numbers. Future studies should consider including more recent ADDM data when they become available.

Despite the above limitations, findings from this study are informative and useful to policymakers, clinicians, and early intervention specialists. These data may inform policymakers on the type of screening programs that may provide the best opportunity to capture most co-occurring conditions/symptoms during routine evaluations of children with ASD. Since co-occurring conditions can be found even at a young age, clinicians may use these data to support screening for co-occurring conditions/symptoms and provide specific interventions. As reported by others, the high prevalence and the diversity of co-occurring conditions/symptoms in ASD suggest the need for a comprehensive system of care for these children. Assessment of co-occurring conditions/symptoms at an early age may provide opportunity for early identification of children with ASD, since these conditions/symptoms increase the likelihood to be in contact with different health care providers.

In conclusion, co-occurring conditions/symptoms are common in ASD, and entail a diverse set of symptoms and developmental courses. Consideration of these co-occurring conditions/symptoms may be useful for early detection and assessment of ASD and also helpful in selecting the most appropriate interventions and services for children with ASD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge CDC ADDM project personnel, ADDM projects coordinators, clinician reviewers, abstractors, data managers, and ADDM investigators at each site who contributed to the ADDM surveillance project and data collection.

Footnotes

Disclaimer The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3521-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Author Contributions GNS conceptualized the original study, analyzed and interpreted the data, wrote the first manuscript of the article, and approved the final version of the article. MJM, DC, MKS and LAS provided feed-back on the design of the study, interpreted the data, reviewed the different versions of the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest All authors do not have a conflict of interest to report.

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study is a secondary data analysis of de-identified data previously collected in a surveillance system. Therefore, formal consent is not required.

References

- Aldinger KA, Lane CJ, Veenstra-VanderWeele J, Levitt P. Patterns of risks for multiple co-occurring medical conditions replicate across distinct cohorts of children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism Research. 2015;8:771–781. doi: 10.1002/aur.1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman ML. Medical comorbidities in autism: Challenges to diagnosis and treatment. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg SJ, Zablotsky B, Avila RM, Colpe LJ, Pringle BA, Kogan MD. Diagnosis lost: Differences between children who had and who currently have an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis. Autism. 2016;20:783–795. doi: 10.1177/1362361315607724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulet SL, Boyle C, Schieve LA. Health care use and health and functional impact of developmental disabilities among US children, 1997–2005. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163:19–26. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone PS, Behl DD, Azor V, Murphy NA. The medical home for children with autism spectrum disorders: Parent and pediatrician perspectives. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010;40:317–324. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0874-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorders aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, 2012. Mortality Morbidity Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries. 2016;65:1–23. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6503a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen DL, Bilder D, Zahorodny W, Pettygrove S, Durkin MS, Fitzgerald RT, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among 4-year-old children in the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2016;37:1–8. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Close HA, Lee LC, Kauffman WE, Law PA. Co-occurring conditions and change in diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2012;129:305–316. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker TR, Elliott MN, Toomey SL, Schwebel DC, Cuccaro P, Emery ST, et al. Racial and Ethnic disparities in the ADHD diagnosis and treatment. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20160407. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croen L, Zerbo O, Qian Y, Massolo ML, Rich S, Sidney S, et al. The health status of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice. 2015;19:814–823. doi: 10.1177/1362361315577517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JR, Lynch FL, Rust KC, Coleman KJ, Madden JM, Owen-Smith AA, et al. Health services utilization among children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;46:910–920. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2634-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidovitch M, Levit-Binnun N, Golan D, Manning-Courtney P. Late diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder after initial negative assessment by a multidisciplinary team. Journal of Behavioral Pediatrics. 2015;36:227–234. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenette P, Dodds L, MacPherson K, Flowerdew G, Hennen B, Bryson S. Factors affecting the age at diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders in Nova Scotia, Canada. Autism. 2011;17:184–195. doi: 10.1177/1362361311413399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulceri F, Morelli M, Santochi E, Cena H, Del Bianco T, Narzisi A, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms and behavioral problems in preschoolers with autism spectrum disorder. Digestive and Liver disease. 2016;48:248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiades S, Szatmari P, Boyle M, Hanna S, Duku E, Zwaigenbaum L, et al. Investigating phenotypic heterogeneity in children with autism spectrum disorder: A factor mixture modeling approach. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:206–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurney JG, McPheeters ML, Davis MM. Parental report of health conditions and health care use among children with and without autism. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescence Medicine. 2006;160:825–830. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.8.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Sikora DM, McCoy R. Prevalence and risk factors of maladaptive behaviour in young children with autistic disorder. Journal of Intellectual and Disability Research. 2008;52:819–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata I, Mohri I, Kato-Nishimura K, Tachibana M, Kuwada A, Kagitani-Shimono K. Sleep problems are more frequent and associated with problematic behaviors in preschoolers with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2016;49–50:86–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ianuzzi D, Cheng E, Broder-fingert &, Bauman ML. Emergency department utilization by individuals with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;45:1096–1102. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2251-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsdottir SL, Saemundsen E, Antonsdottir IS, Sigurdardottir S, Olason D. Children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder before or after age of 6 years. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011;5:175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Kielinen M, Rantala H, Timonen E, Lina SL, Moilanen I. Associated medical disorders and disabilities in children with autistic disorder. A population-based study. Autism. 2004;8:49–59. doi: 10.1177/1362361304040638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan MD, Strickland BB, Blumberg SJ, Singh G, Perrin JM, Van Dyck PC. A national profile of health care experiences and family impact of autism spectrum disorder among children in the United States, 2005–2006. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1149–1158. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakowiak P, Goodlines B, Hertz-Picciotto I, Croen LA, Hansen RL. Sleep problems in children with autism spectrum disorders, developmental delays, and typical-development: A population-based study. Journal of Sleep Research. 2008;17:197–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00650.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lever AG, Geurts HM. Psychiatric co-occurring symptoms and disorders in young, middle-aged, and older adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;46:1916–1930. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2722-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy SE, Giarelli E, Li-Ching L, Schieve LA, Kirby RS, Cuniff C, et al. Autism spectrum disorder and co-occurring developmental, psychiatric, and medical conditions among children in multiple populations of the United States. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2010;31:267–275. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181d5d03b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundstrom S, Reichenberg A, Melke J, Rastam M, Kerekes N, Lichtenstein P, et al. Autism spectrum disorders and coexisting disorders in a nationwide Swedish twin study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015;56:702–710. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusdottir K, Saemundsen E, Einarsson BL, Magnusson P, Njardvik U. The Impact of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder on adaptive functioning in children diagnosed late with autism spectrum disorder. A comparative analysis. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2016;23:28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Malow BA, Katz T, Reynolds AM, Shui A, Carno M, Conolly HV, et al. Sleep difficulties and medications in children with autism spectrum disorders: A registry study. Pediatrics. 2016;137:S98–S104. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2851H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DS, Ittenbach RF, Levy JSE, Pinto-Martin JA. Disparities in the diagnoses received prior to a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37:1795–1802. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0314-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannion A, Leader G. An investigation of comorbid psychological disorders, sleep problems, gastrointestinal symptoms and epilepsy in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A two year follow-up. Research in Autism Disorders. 2016;22:20–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek MO, Handen BL, Wodka EL, Nowinski L, Butter E, Engelhardt CR. Age at first autism spectrum diagnosis: The role of birth cohort, demographic factors, and clinical features. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2014;35:516–569. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas JS, Carpenter LA, Ling LB, Jenner W, Charles JM. Autism spectrum disorders in preschool-aged children: Prevalence and comparison to a school-aged population. Annals of Epidemiology. 2009;19:808–814. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock G, Amendah D, Ouyang L, Grosse SD. Autism spectrum disorders and health care expenditures: The effects of co-occurring conditions. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2012;33:2–8. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31823969de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posserud M, Hysing M, Helland W, Gillberg C, Lundervold AJ. Autism traits: The importance of co-morbid problems for impairment and contact with services. Data from the Bergen child study. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2018;72:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar F, Baird G, Chandler S, Tseng E, O’Sullivan T, Howlin P, et al. Co-occurring psychiatric disorders in preschool and elementary school-aged children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;45:2283–2294. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2361-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieve LA, Gonzalez V, Boulet SL, Visser SN, Rice CE, Van Naarden Braun K, et al. Concurrent medical conditions and health care use and needs among children with learning and behavioral developmental disabilities, National Health Interview Survey, 2006–2010. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2012;33:467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikora DM, Vora P, Coury DL, Rosenberg D. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms, adaptive functioning, and quality of life in children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. 2012;130:S91–S99. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0900G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonoff EM, Pickles AP, Charman TP, Chandler SP, Loucas T, Baird G. Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:921–929. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soke GN, Maenner MJ, Christensen D, Kurzius-Spencer M, Schieve LA. Brief report: Estimated prevalence of a community diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder by age 4 years in children from selected areas in the United States in 2010: Evaluation of Birth cohort effects. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2017;47:1917–1922. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3094-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supekar K, Iyer T, Menon V. The influence of sex and age on prevalence rates of comorbid conditions in autism. Autism Research. 2017;10:778–789. doi: 10.1002/aur.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vohra R, Madhavan S, Sambamoorthi U. Emergency department use among adults with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;46:1441–1454. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2692-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse L, London E, Gillberg C. ASD validity. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;3:302–329. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins LD, Baio J, Schieve LA, Lee LC, Nicholas J, Rice C. Retention of autism spectrum diagnoses by community professionals: Findings from the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 2000, and 2006. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2012;45:3183–3194. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182560b2f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins LD, Levy SE, Daniels J, Schieve L, Croen LA, DiGuiseppi C, et al. Autism spectrum disorders symptoms among children enrolled in the Study to Explore Early Development (SEED) Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;45:3183–3194. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2476-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins LD, Rice C, Baio J. Developmental regression in children with autism spectrum disorders identified by a population-based surveillance system. Autism. 2009;13:357–374. doi: 10.1177/1362361309105662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YT, Maenner MJ, Wiggins LD, Rice CE, Bradley CE, Lopez ML, et al. Retention of autism spectrum disorder diagnosis: The role of co-occurring conditions in males and females. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2016;25:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeargin-Allsopp M, Rice C, Karapurkar T, Doenberg N, Boyle C, Murphy C. Prevalence of autism in a US metropolitan area. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:49–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.