Abstract

Background

Half of all Americans have a chronic disease. Promoting healthy behaviors to decrease this burden is a national priority. A number of behavioral interventions have proven efficacy; yet even the most effective of these has high levels of non-response.

Objectives

In this study, we explore variation in response to an evidence-based community health worker intervention for chronic disease management.

Research Design

We used a convergent parallel design that combined a randomized controlled trial with a qualitative process evaluation that triangulated chart abstraction, in-depth interviews and participant observation.

Subjects

Eligible patients lived in a high-poverty region and were diagnosed with two or more of the following chronic diseases: diabetes, obesity, hypertension or tobacco dependence. There were 302 patients in the trial, 150 of whom were randomly assigned to the CHW intervention. Twenty patients and their community health workers were included in the qualitative evaluation.

Results

We found minimal differences between responders and non-responders by sociodemographic or clinical characteristics. A qualitative process evaluation revealed that health behavior change was challenging for all patients and most experienced failure (i.e. gaining weight or relapsing with cigarettes) along the way. Responders seemed to increase their resolve after failed attempts at health behavior change, while non-responders became discouraged and 'shut down'.

Conclusions

Failure is a common and consequential aspect of health behavior change; a deeper understanding of failure should inform chronic disease interventions.

Keywords: Health behavior, behavior change, community based interventions, chronic disease, qualitative research

Introduction

Chronic diseases are responsible for 7 of 10 deaths in the United States.1 Many of these deaths could be prevented by changes in health behaviors such as diet, physical activity and smoking.2,3 Accordingly, it is a national priority to develop and scale effective interventions for promoting healthy behavior, particularly in lower income populations where the risk of chronic disease is disproportionately high.2 A number of approaches have been effective including: chronic disease self-management training,4,5 structured diabetes prevention programs,6,7 financial incentives,8 digital automated monitoring,9 and support from community health workers (CHWs).10–12

Yet, even the most effective of these interventions does not work for all people. For example, only 60% of participants in the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) intensive lifestyle intervention achieved exercise goals and only 40% met weight loss goals.10 We know surprisingly little about what distinguished responders from non-responders or reasons for non-response.7 Non-responders in the DPP trial were similar to responders across all measured baseline sociodemographic characteristics.10 Other behavioral intervention studies4,6,8,13 have similarly concluded that baseline measures explain little of the variation in treatment response.

Numerous systematic reviews7,10,14 and research funders15 have identified the same knowledge gap: for whom do effective chronic disease interventions work/not work and why? Answering this question is critical so that interventions can be targeted and tailored across populations.

Our study team has developed IMPaCT16–19 (Individualized Management for Patient-Centered Targets), a standardized CHW intervention tested in two prior randomized clinical trials16,19 including a recent trial of outpatients with multiple chronic diseases.16 The primary analysis of this trial demonstrated that the intervention improved control of diabetes, obesity, smoking, mental health and quality of primary care while reducing hospital admissions.16 However, despite overall effectiveness, 36.7% of intervention patients had worsened chronic disease control over the study period.

We were interested in learning who these non-responders were and why their chronic diseases got worse despite support. Here, we present a secondary analysis of trial data exploring differences between intervention responders and non-responders. We also use a concurrent qualitative evaluation to uncover differences not otherwise measured.

Methods

Randomized trial

We used a convergent parallel design20 that combined a randomized controlled trial with a qualitative process evaluation. Details of this trial have been previously described.16–18 Briefly, enrollment took place between July 2013 and October 2014 at two urban internal medicine clinics. Eligible patients lived in a high-poverty region and were diagnosed with two or more of the following chronic diseases: diabetes, obesity, hypertension or tobacco dependence. We did not require patients to be in poor control of their chronic disease. After enrollment, patients selected one of their chronic diseases to focus on during the study and set a chronic disease management goal in consultation with their primary care provider.

Trained research assistants collected baseline biometric (glycosylated hemoglobin (Hba1C), body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure (SBP) or cigarettes per day (CPD)) and survey data (including the Patient Activation Measure,21 a 13-item measure that assesses patient’s knowledge, skill, and confidence for self-management). After the baseline survey, patients were randomized to goal-setting alone or goal-setting plus six months of the IMPaCT intervention. Six months later, blinded research assistants conducted study visits to assess outcomes including the primary outcome: change in selected chronic disease.

We defined non-responders as those individuals who had worsening of their selected chronic disease (as measured by an increase in Hba1C, BMI, SBP or CPD between enrollment and 6-month follow-up.) Responders were those who improved, or at least maintained control of their selected chronic disease. We reasoned that for low-income patients with multiple chronic diseases, maintaining control can be considered a victory and we didn’t want to consider these people non-responders.

Intervention

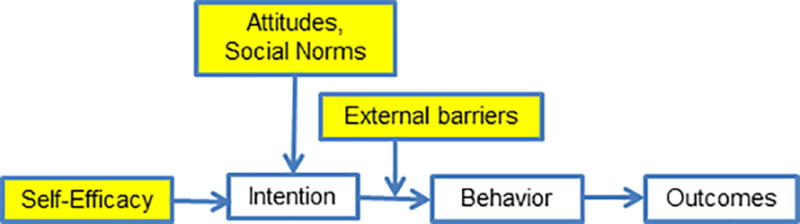

IMPaCT is theory-based and builds on the Reasoned Action Approach23,24 (Figure 1) an evidence-based framework for behavior-dependent outcomes. In this framework, attitudes, social norms, and self-efficacy shape an individual’s intention to initiate a behavior. A strong intention predicts performance of behavior unless there are external barriers. CHWs are trained laypeople who share socioeconomic backgrounds with patients and have high levels of empathy. These characteristics allow CHWs to influence attitudes, shift social norms, address external barriers, and bolster self-efficacy through strategies like motivational interviewing (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Reasoned Action Approach with IMPaCT Intervention Targets. Source: Adapted from Rimer, Glanz Theory At A Glance.53

At their first meeting, CHWs and patients discussed social and behavioral determinants affecting patients’ health. CHWs then helped patients create action plans to achieve their chronic disease management goals. CHWs provided six months of tailored support, contacting patients at least weekly, to help patients execute their action plans. Over the six-month period, CHWs encouraged patients to monitor progress on their selected chronic disease goal each week (i.e. track blood sugars, weight, daily cigarettes or blood pressure). If patients failed to make progress (for instance, if their weight was going up instead of down), CHWs used a semi-structured script to provide empathic motivational interviewing and troubleshoot barriers. CHWs also facilitated a weekly support group designed to foster peer networks.

The IMPaCT model provides guidelines for program infrastructure including hiring, training and supervision.25 CHWs were recruited by circulating job descriptions through a network of community-based organizations (e.g. neighborhood associations, churches). Job applicants were screened through group and individual interviews and employer reference checks to identify individuals who were good listeners, non-judgemental and reliable.

CHWs went through a month-long training that covers topics such as action-planning, motivational interviewing and trauma-informed care.

CHW fidelity to the training and care model was reinforced through several strategies. Newly trained CHWs were apprenticed to a senior community health worker until they demonstrated proficiency in pre-specified core competences. CHWs were then observed by their supervisor, typically a master’s level social worker, to confirm that adherence to work practices as described in training and in intervention manuals. Supervisors continued to assess intervention fidelity through a recurring series of weekly assessments: reviews of documentation, observation of CHWs in the field, telephone calls to patients, a performance dashboard of process and outcome metrics and weekly meetings with each CHW.

Qualitative process evaluation

The goal of this process evaluation was to understand patient and CHW perspectives on the intervention, comparing responders and non-responders.

The evaluation triangulated multiple data sources collected at the completion of the six-month intervention: (1) abstraction of medical records and CHW documentation; (2) asynchronous qualitative interviews with patient and their CHW that included stimulated recall of key topics gleaned from the chart abstraction; and (3) participant observation notes recorded at patient interviews. We used the Reasoned Action Approach to develop structured data collection guides for each source probing for key domains such as self-efficacy, social norms, intention of performing health behaviors and external barriers.

Trained interviewers (unknown to study participants) conducted patient interviews either in patients’ homes or private clinic rooms, based on preference, while a research assistant recorded participant observation notes. Patients and their CHWs were interviewed at separate times in no particular sequence without any reference to each other’s interviews. Interviewers asked open-ended questions to encourage patients to speak freely and in their own words. Interviewers asked probing follow-up questions to clarify statements, explore important themes, and establish timelines of events. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed.

We purposively sampled responders and non-responders, and planned to obtain 40 interviews (20 patients and 20 CHWs) to allow for thematic saturation, the point at which no new qualitative codes are created or refined and code frequency stabilizes.25 We performed iterative data collection and analysis to determine whether new themes were emerging, assess saturation, and inform purposive sampling. For instance, if we realized that results among hypertensive patients were saturated, but new themes were still emerging among smokers, we purposively sampled more smokers.

Analysis

Quantitative analysis

We used the above described randomized controlled trial dataset, focusing on the subgroup of individuals in the CHW intervention arm. Response was defined as a dichotomous variable: improvement or maintenance (negative or zero value) for change in in patients’ selected chronic disease.

We descriptively compared baseline characteristics of responders and non-responders in the CHW intervention arm using χ2 tests for categorical variables and 2-tailed, unpaired t tests, as well as the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables.

We then built a multivariable logistic regression model including baseline variables (main effects and interaction terms) that were associated (p<0.2) with the outcome in the descriptive analysis. We also included in this model conceptually driven variables: basic demographic and clinical variables (age, gender, race, prior hospital use) and domains of the Reasoned Action Approach (self-efficacy and commitment to chronic disease management goals, social support and key external barriers as reflected by income, employment, drug or alcohol use and perceived stress.) We then used stepwise regression to restrict the model to variables with a threshold of significance (p<0.1).

Qualitative analysis

All four data sets for each patient (chart, asynchronous dyadic interviews and observation notes) were uploaded into QSR NViVO 10.0 (QSR International) for analysis. We used an integrated approach,26 developing a coding schema that included major ideas that emerged from a close reading as well as a set of a priori codes corresponding to key domains of the Reasoned Action Approach. Two trained research assistants coded all data and iteratively met to modify the coding schema and interview guide for clarity.26 At coding meetings, inter-rater reliability (kappa) was calculated using the NViVO coding comparison function. Discrepancies (a node where inter-rater reliability was less than 0.8) were discussed to facilitate either consensus or a deeper understanding of the issue at hand. The final inter-rater reliability across all data sources was 0.93.

Data were sorted by code based on intervention response using the matrix query function of NViVO. These reports were carefully read in order to understand prominent themes including differences between responders and non-responders. We used member checking27 – a technique in which findings are validated with members of the study population– by discussing findings with CHWs.

The themes reported below are derived from the integrated analysis of all four data sources.

Results

Quantitative

Of the subgroup of patients who received CHW support (n=150), 63.3% maintained or improved control of their selected chronic disease control, while 36.7% worsened. In the descriptive analysis, responders and non-responders were similar across all measured characteristics with the exception of race, chronic disease selection, baseline chronic disease control, goal difficulty and patient activation measure (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients receiving intervention (n=150)

| Responder (n=95) No (%) or mean ± SD |

Non-responder (n=55) No (%) or mean ± SD |

P Value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||||

| Age | 56.8 ±13.3 | 56.5 ±14.4 | 0.87 | |

| Female | 73 (76.8) | 42 (76.4) | 0.95 | |

| African American | 93 (97.9) | 49 (89.1) | 0.02 | |

| Employed | 19 (20.2) | 11 (20.0) | 0.98 | |

| Household Income <15K | 39 (52.0) | 24 (53.3) | 0.89 | |

| Low Social Support | 16 (17.0) | 13 (23.6) | 0.33 | |

| Chronic disease focus | ||||

| Tobacco dependence | 13 (13.7) | 2 (3.6) | 0.05 | |

| Systolic blood pressure | 13 (13.7) | 12 (21.8) | 0.20 | |

| Diabetes | 24 (25.3) | 12 (21.8) | 0.63 | |

| Obesity | 45 (47.4) | 29 (52.7) | 0.53 | |

| Chronic disease management goal | ||||

| Goal difficulty (baseline-goal difference) | ||||

| Tobacco dependence (cigarettes/day) | −11.9 ±8.7 | −0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.06 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | −12.7 ±14.8 | −0.9 ± 12.5 | 0.02 | |

| Diabetes (Glycosylated hemoglobin %) | −1.6 ±2.3 | −0.6 ± 1.0 | 0.39 | |

| Obesity (Body mass index) | −2.5 ±1.3 | −2.4 ± 0.9 | 0.98 | |

| Commitment to goal (3–2013;24 is not committed) | 7.3 ±1.0 | 7.3 ± 1.0 | 0.46 | |

| Self-efficacy of achieving goal (2–16 is low) | 7.0 ±1.3 | 7.2 ± 1.1 | 0.30 | |

| Goal attention Scale (4–32 low)* | 23.2±7.3 | 22.8 ± 7.2 | 0.70 | |

| Goal recall* | 28 ±42.4 | 14 ± 35.9 | 0.51 | |

| Clinical | ||||

| Baseline control of selected chronic disease | ||||

| Tobacco dependence (cigarettes/day) | 11.9 ±8.7 | 0.8 ±0.4 | 0.06 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 148.8 ±16.0 | 133.3 ±13.1 | 0.01 | |

| Diabetes (Glycosylated hemoglobin %) | 9.1 ±3.4 | 7.9 ± 1.2 | 0.65 | |

| Obesity (Body mass index) | 40.0 ±7.7 | 41.2 ± 8.5 | 0.55 | |

| Baseline self-rated health (0–100 high) | 36.5 ± 12.0 | 36.6 ± 11.5 | 0.95 | |

| Number of hospitalizations 12 months prior | 0.7 ±2.3 | 1.0 ± 2.7 | 0.26 | |

| Psychosocial | ||||

| Perceived stress (0–12 high) | 6.1 ±3.7 | 5.6± 3.7 | 0.44 | |

| Trauma History Questionnaire (0–24 high) | 6.6 ±3.7 | 7.2 ± 5.0 | 0.66 | |

| Alcohol overuse | 18 19.2) | 13 (23.6) | 0.51 | |

| Drug use | 13 (13.8) | 7 (12.7) | 0.85 | |

| Patient Activation Measure (0–100 high) | 57.9 ±12.5) | 63.5 ± 13.7 | 0.03 | |

| CHW assigned to patient | ||||

| CHW | 0.44 | |||

| A | 31 (32.6) | 18 (32.7) | ||

| B | 35 (36.8) | 15 (27.3) | ||

| C | 28 (29.5) | 22 (40.0) | ||

| D | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Types of action plans worked on with CHW | ||||

| Clinical (e.g. deal with pain) | 3 (0.9) | 3 (1.57) | 0.42 | |

| Health system navigation (e.g. get apt) | 27 (8.4) | 17 (8.9) | ||

| Psychosocial (e.g. family stress) | 68 (21.1) | 53 (27.8) | ||

| Resources (e.g. transportation) | 27 (8.4) | 14 (7.3) | ||

| Health behavior (e.g. joining gym) | 197 (61.2) | 104 (54.5) | ||

Goal attention and recall were measured at 6-month follow-up. All other measures were assessed at baseline.

In the final multivariable logistic regression model, the only significant predictor of response was an interaction between patient activation and study arm (OR 1.03, 95%CI [1.05, 1.01], p=0.05): patients with lower activation were more likely to respond to the intervention. African American patients appeared more likely to respond to the intervention (OR 13.3, 95% CI [1.3, 139.6, p=0.005); however this estimate was unstable because there were only eight non-African Americans in the sample.

There was no difference in intervention response based on which CHW was delivering the intervention. There were no differences in the types of action plans patients and their CHWs worked on together (Table 1).

Qualitative

Ninety trial participants were screened for interest in the qualitative evaluation. Of the seventy-six who consented, 24 were purposively sampled and invited to participate. Three of the individuals were not reachable at the time of the interview and one was no longer interested, leaving 20 (10 responders, 10 non-responders) in the final sample (Table 2) in addition to 20 dyad interviews with four CHWs.

Table 2.

Characteristics of qualitative evaluation participants

| Responder (n=10) No (%) or mean ± SD |

Non-responder (n=10) No (%) or mean ± SD |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Age | 56.9 ±16.0 | 59.7 ± 15.0 | |

| Female | 6 (60) | 8 (80) | |

| African American | 10 (100) | 8 (80) | |

| Employed | 1 (10) | 2 (20) | |

| Household Income <15K | 4 (50) | 5 (60) | |

| Low Social Support | 2 (20) | 3 (30) | |

| Clinical | |||

| Baseline control of selected chronic disease | 0.5 ±NA | 13.0 ±9.9 | |

| Tobacco dependence (cigarettes/day) | 160.0 ±21.2 | 142.0 ±2.8 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 9.5 ± 3.1 | 8.0 ± NA | |

| Diabetes (Glycosylated hemoglobin %) | 45.8 ± 18.8 | 38.4 ± 7.6 | |

| Obesity (Body mass index) | |||

| Baseline self-rated health (0–100 high) | 41.4 ± 7.3 | 38.0 ± 8.0 | |

| Number of hospitalizations 12 months prior | 2.4 ± 6.3 | 0.7 ± 0.9 | |

| Chronic disease management goal | |||

| Goal difficulty (baseline-goal difference) | |||

| Tobacco dependence (cigarettes/day) | −0.5 ±NA | −13.0 ±9.9 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | −25.0 ±28.3 | 3.0 ±4.2 | |

| Diabetes (Glycosylated hemoglobin %) | −1.8 ± 2.0 | −1.0 ± NA | |

| Obesity (Body mass index) | −22.8 ± 3.2 | −16.4 ± 3.2 | |

| Difficult goal | 5 (50) | 1 (10) | |

| Commitment to goal (3 – 24 is not committed) | 6.5 ± 3.0 | 3.6 ± 1.1 | |

| Goal attention Scale (4–32 high) | 21.6 ± 8.4 | 21.8 ± 6.6 | |

| Self-efficacy of achieving goal (2–16 is low) | 3.4 ± 1.7 | 3.4 ± 1.6 | |

| Goal recall at 6 month follow-up | 4 (40) | 3 (30) | |

| Psychosocial | |||

| Perceived stress (0–12 high) | 5.1 ± 3.1 | 8.3 ± 4.2 | |

| Trauma History Questionnaire (0–24 high) | 6.8 ± 3.0 | 9.0 ± 6.5 | |

| Alcohol overuse | 0 (0) | 4 (40) | |

| Drug use | 3 (30) | 3 (30) | |

| Patient Activation Measure (0–100 high) | 56.9 ± 9.2 | 53.7 ± 13.0 | |

|

| |||

| (n = 4) | |||

| No (%) or mean ± SD | |||

| CHW Demographics | |||

| Age | 43.75 ±9.2 | ||

| Female | 2 (50) | ||

| African American | 4 (100) | ||

Common themes

There were several themes common across responders and non-responders. Most patients describe being motivated at the time of study enrollment and considering chronic disease management a high priority. CHWs affirmed the uniformity of initial motivation; in fact they had trouble predicting who would eventually become a responder versus non-responder. Ninety percent of patients expressed a positive opinion of their CHW. Charts and interviews revealed that responders and non-responders received similar types of social support from their CHWs. This included emotional support (“I [told CHW] about things going on with my children’s father. She really understood” [Female patient, 35y]), appraisal support (“When I was doing well, [CHW] said she proud of me” [Female patient, 80y]) and informational support (“[CHW] got me a list of stuff, what to eat and what not to eat” [Male patient, 48y]).

Charts and interviews revealed common barriers across both groups including limited access to resources like healthy food, stress, trauma histories, disability, and insurance issues. One notable barrier endorsed by half of all patients was grief associated with death of family members, (“I lost my only child and that was a very [big] shock to me…and then after that my grandson, his only son, dropped dead” [Female patient, 88y]). Patients commonly talked about doing well with their health behavior change until a family death disrupted them entirely.

Differences between responders and non-responders

Despite similarities, there were a number of important qualitative differences distinguishing responders versus non-responders (Table 3).

Table 3.

Representative quotes

| Responders | Non-responders | |

|---|---|---|

| Influence of social norms | “I ain’t never talked about [my goals] with nobody so I was just doing it”[Male patient, 49yr]. | “Things I’m not supposed to have, [my daughter] makes it a point to bring it…Like she might come in here on the weekend or during the week with the lemon meringue pie, a half a dozen cookies, those TV dinners and whatnot, all these I’m not supposed to have” [Female patient, 84yr]. |

| Specific versus vague barriers | “The thing that makes it hard is when we have parties and things or family get-togethers, and you just have all this different foods or cakes and things. Now, where I might have had two helpings of macaroni and cheese [previously], I only have one” [Female patient, 36 yr]. | “Eventually it just came to a point where, what the hell, if the cigarettes kill me, let them kill me, okay, I’ll be gone, I don’t have to deal with this” [Female patient, 59yr] |

| Response to failure | “I started to gain back the weight. It wasn’t like I got upset. Nothing like that. [CHW] and I talked through it and it made me more aware of what I was doing, eating a lot of cakes. And it made me work extra hard in the gym, that’s all” [Male patient, 40yr]. | “I felt at ease with [the CHW], he was offering to help me with my electric bill or family stuff. But I felt that no, I’m not making these goals, I’m not doing what I’m supposed to do, so I shut down” [Female patient, 59 yr]. |

Influence of social norms

Responders sometimes enlisted the help of supportive friends or family to do things like exercise or reinforce smoking cessation. However, when friends or family were not supportive, responders seemed to pull away from their influence. “[My family] didn’t take me serious [about quitting smoking]. It made me more determined. So I really didn’t talk about it with anybody. I just let them know I don’t smoke no more” [Male patient, 79y]. These responders created new social norms by drawing closer to their CHWs or the support group. For instance, a CHW described how a patient gravitated to the support group when her family continued to offer her unhealthy food: “[She] saw that she wasn’t alone and met other people working on the same goals.”[CHW]

In contrast, non-responders seemed to have a harder time disentangling from negative social norms. One CHW remarked: “[The patient] had three people who lived in her house who all smoked and every time they would light up, she felt the need to light up. And I had asked her if she wanted to ask her family members to light up outside. And I remember her – she didn’t agree to that.” “It makes it difficult,” this same patient explained. ”Feeling that I didn’t have anybody at home working with me to try to do things that needed to be done. That brought about a lot of stress and some anger and I smoked a lot” [Female patient, 59y].

Specific vs. vague barriers

Responders commonly described concrete barriers, such as unhealthy food at social events, inclement weather, or pain that made it difficult to exercise. Due to the concrete, often temporary nature of these barriers, responders routinely could work with CHWs to find solutions.

Non-responders described vague barriers and as a result could not easily identify solutions. They used phrases like “It’s nothing specific” or “It was situations beyond my control.” They expressed lack of self-awareness around why they struggled on their health goals: “I don’t know what happened. My sugar just got out of control.”

Response to failure

All patients found behavior change to be challenging, and most had periods of failure (i.e. gaining weight or relapsing with cigarettes) along the way. Responders were more likely to react to these failures with resolve. A CHW described a patient “who would call and say like, oh, I had a setback. She gained three or four pounds. But she didn’t make a bad week turn into a bad month. She got right back on track as soon as she could” [CHW]. Another patient explained setbacks with childcare and other family stressors. “So I was going through more of a depression. But I didn't let that get me down either. I was making sure I would get to my goal”[Female patient, 39yr].

Contrastingly, non-responders often started off optimistically, but were discouraged by failure and became avoidant. They described feelings of self-blame that often led them to disengage from the intervention. One CHW described a patient who “got kinda frustrated because she said she didn’t see the weight coming off like it was coming off before. I just encouraged her to just keep working on it [CHW]”. However, as the patient explained: “[The program] was coming to the end, and I was telling her I hadn’t reached the goal. She would tell me don’t get discouraged. But, I got discouraged. I mean, what you gonna do? Either you do it or you don’t” [Female patient, 56yr].

In some instances, discouragement was prompted by CHWs asking patients to self-monitor disease measures (i.e. blood sugar, weight, cigarettes or blood pressure). Monitoring forced patients to confront their progress or lack thereof on their goals and seemed to create a type of aversive feedback: “She keep texting me and calling me to ask about weight. But some of the texts and some of the calls, I never replied back, because I feel ashamed. Because she would be like, let’s do this – it’s going to be good for you. At that time, when I answer, yeah, yeah, yeah. But I hang up, f**k it, I don’t want to do that s**t because I don’t see the change on me [Male patient, 40yr].”

Interestingly, when CHWs adjusted their approach and deliberately stopped discussing self-monitoring or health goals, patients sometimes became re-engaged. As told from a CHW’s perspective: “She was avoiding my calls because her sugars were high. So I left messages purely to make her smile. She began to call me…checking her sugars, without me asking! [CHW]”

Discussion

We found minimal quantitative clues to explain differences in response to an evidenced-based chronic disease management intervention. The intervention was slightly more effective among patients with lower baseline patient activation.

The qualitative evaluation revealed several common external barriers that have been well described in the literature, such as lack of healthy foods29 and insurance problems30. Notably, this high-risk group described grief as a common and tragic deterrent to health behavior change.

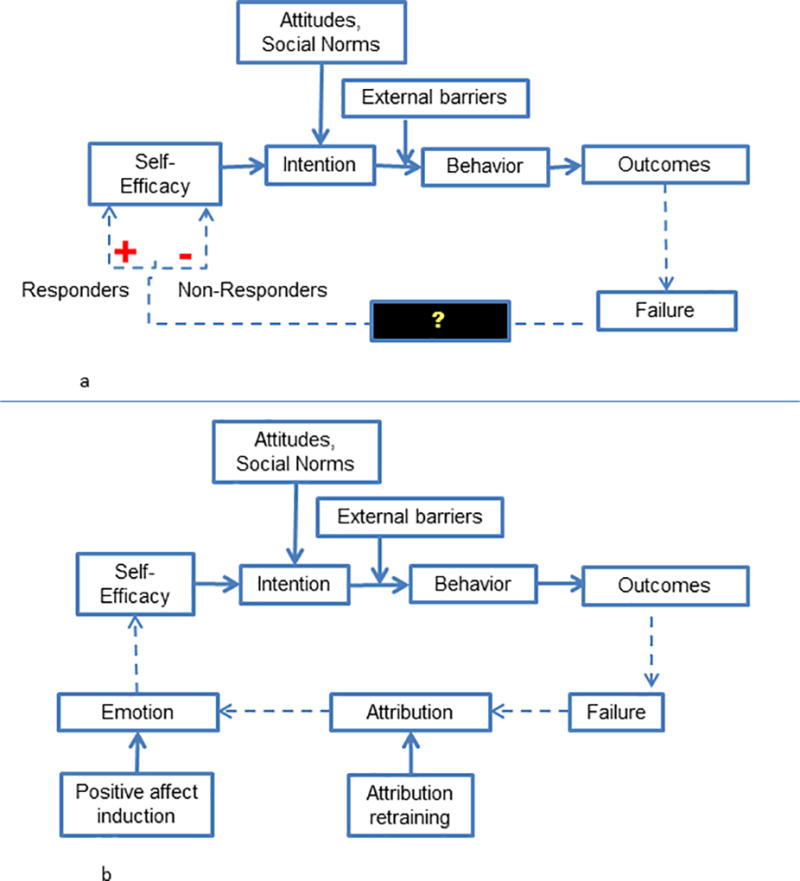

The most striking difference between responders and non-responders was their reactions to failure. By encouraging patients to monitor progress on chronic disease goals, CHWs activated a feedback loop that provided patients with signals of success or failure (Figure 2a). Responders seemed to be motivated by failure and went on to “work even harder” with their CHW on health behavior change, ultimately improving chronic disease control. Non-responders appeared discouraged by failure and avoided their CHWs. Interestingly, these patients may have been re-engaged when CHWs stopped focusing on the “numbers” and provided pure emotional support.

Figure 2.

a: Feedback loop created divergent reactions to failure

b: Pathways of response to failure and intervention targets

These findings raise a critical question: what caused these two subgroups of patients, so similar by most measures, to have such different reactions to failure?

Recent behavioral science theories31,32 may explain these individual differences. Failure is processed in two stages: attribution (‘Why did I fail?’) and emotion (‘How do I feel about the failure?’). When people attribute failure to concrete and controllable causes (‘I failed this test because I didn’t study’), they feel regret,33 which can sharpen motivation, increase self-efficacy and improve behavior.33,34 Contrastingly when people attribute failure to vague or uncontrollable causes (‘I failed because I am stupid’), they feel ashamed and hopeless.35,36 These negative emotions can trigger avoidance as a way to preserve self-esteem.31,37

Fortunately, two behavioral interventions seem to promote resolve instead of avoidance: attribution retraining38,39 and positive affect induction.31 Attribution retraining is a form of cognitive reframing that encourages participants to interpret failures as controllable.38,39 This retraining has been tested in education, and helps students academic performance after failure,38 with the greatest benefit for students predisposed to avoidance.40,41 Few studies have translated attribution retraining to the sphere of health behavior.38 Positive affect induction uses strategies such as unexpected compliments or gifts42,43 and self-affirmation44 to induce positive emotion. Two healthcare studies demonstrated that positive affect induction improved adherence to hypertensive medications45 and doubled physical activity among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.46

Our results and insights from the behavioral science literature are synthesized in Figure 2b.

This study has several limitations. This was a single-center study which may not be generalizable beyond an urban, disadvantaged population. The study was not powered to detect differences between responders and non-responders. For instance, although we did not see differential response across the CHW delivered the intervention, it is difficult to know with certainty whether non-response was due to patient rather than CHW characteristics. However, there were several safeguards in place to reinforce CHW fidelity to the intervention and the qualitative data supported the notion that care was uniform. Another limitation was that qualitative interviews may have been subject to recall bias which we attempted to minimize by using chart-stimulated recall. Finally, results were validated by member-checking with CHWs but not with patients.

Sustained health behavior change is incredibly challenging and most people fail along the way. Self-monitoring –-- a cornerstone of many health promotion strategies like wearable tracking devices51 or ‘Know Your Numbers’ campaigns52—can heighten awareness of these failures. How a patient ultimately responds to failure may be an important and modifiable determinant of future behavior and chronic disease outcomes.

Yet failure and non-response are understudied. Quantitative analyses examining non-response are often unrevealing, likely because we are not measuring the right baseline variables. We should measure not only demographic, but psychological characteristics (e.g. grit,47 response to failure,48 or coping style49) in intervention trials. Understanding predictors of non-response could inform targeting of interventions for maximal benefit. Alternately, interventions could be modified to better serve would-be non-responders; for instance based on these findings, the study team is planning to train IMPaCT CHWs on positive affect induction and attribution retraining. Perhaps in the future, CHWs will be able to help patients face the failures that are an inevitable part of behavior change.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Disclosure of funding: This work was supported by funding from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Institutional Career Development (K12) grant, a grant from the University of Pennsylvania Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, and funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K23 HL128837).

Footnotes

Statement of conflict of interests: No authors on this paper have any conflicts of interest from the past 3 years.

Contributor Information

Merritt Edlind, University of Pennsylvania.

Nandita Mitra, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, 622 Blockley Hall, 423 Guardian Drive, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

David Grande, University of Pennsylvania, 3641 Locust Walk, Colonial Penn Center 407, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

Frances K. Barg, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, 915 Blockley Hall, 423 Guardian Drive, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

Tamala Carter, University of Pennsylvania Health System, 3801 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

Lindsey Turr, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, 1002 Blockley Hall, 423 Guardian Drive, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

Karen Glanz, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, 801 Blockley Hall, 423 Guardian Drive, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

Judith Long, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, 1201 Blockley Hall, 423 Guardian Drive, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

Shreya Kangovi, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, 1233 Blockley Hall, 423 Guardian Drive, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

References

- 1.Control CfD, editor. At a Glance 2015 National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Fact Sheet. Atlanta, GA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation. 2005 Mar 15;111(10):1233–1241. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158136.76824.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schroeder SA. Shattuck Lecture. We can do better--improving the health of the American people. N Engl J Med. 2007 Sep 20;357(12):1221–1228. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa073350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med Care. 1999 Jan;37(1):5–14. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199901000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, et al. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med Care. 2001 Nov;39(11):1217–1223. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002 Feb 07;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diabetes Prevention and Control: Combined Diet and Physical Activity Promotion Programs to Prevent Type 2 Diabetes Among People at Increased Risk: Commnuity Preventive Services Task Force. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volpp KG, Troxel AB, Pauly MV, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of financial incentives for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 2009 Feb 12;360(7):699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0806819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLean G, Band R, Saunderson K, et al. Digital interventions to promote self-management in adults with hypertension systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2016 Apr;34(4):600–612. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Force CPST, editor. Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control: Interventions Engaging Community Health Workers. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim K, Choi JS, Choi E, et al. Effects of Community-Based Health Worker Interventions to Improve Chronic Disease Management and Care Among Vulnerable Populations: A Systematic Review. Am J Public Health. 2016 Apr;106(4):e3–e28. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski JL, Nishikawa B, et al. Outcomes and costs of community health worker interventions: a systematic review. Med Care. 2010 Sep;48(9):792–808. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35b51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffiths C, Motlib J, Azad A, et al. Randomised controlled trial of a lay-led self-management programme for Bangladeshi patients with chronic disease. Br J Gen Pract. 2005 Nov;55(520):831–837. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control: Interactive Digital Interventions for Blood Pressure Self-Management: Community Preventive Services Task Force. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institute PCOR, editor. Putting Research to Work for Individual Patients. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kangovi S, Mitra N, Grande D, Huo H, Smith RA, Long JA. Community Health Worker Support for Disadvantaged Patients With Multiple Chronic Diseases: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Public Health. 2017 Aug 17;:e1–e8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kangovi S, Mitra N, Turr L, Huo H, Grande D, Long JA. A randomized controlled trial of a community health worker intervention in a population of patients with multiple chronic diseases: Study design and protocol. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017 Feb;53:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kangovi S, Mitra N, Smith RA, et al. Decision-making and goal-setting in chronic disease management: Baseline findings of a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2016 Sep 25; doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kangovi S, Mitra N, Grande D, et al. Patient-centered community health worker intervention to improve posthospital outcomes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Apr;174(4):535–543. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guetterman TC, Fetters MD, Creswell JW. Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Results in Health Science Mixed Methods Research Through Joint Displays. Ann Fam Med. 2015 Nov;13(6):554–561. doi: 10.1370/afm.1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004 Aug;39(4 Pt 1):1005–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanfer R, Ackerman PL. Motivation and Cognitive-Abilities - an Integrative Aptitude Treatment Interaction Approach to Skill Acquisition. J Appl Psychol. 1989 Aug;74(4):657–690. Table 651. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior : the reasoned action approach. New York: Psychology Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fishbein M. Paper presented at: Theorists Workshop. Bethesda, MD: 1992. Factors Influencing Behavior and Behavior Change. Final Report. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kangovi S, Leri D, Clayton C, Lang A, Grande D, Long JA, Rosin R. Penn Center for Community Health Workers. 2013 http://chw.upenn.edu/, 2016.

- 26.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007 Aug;42(4):1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernard HR, Ryan GW. Analyzing qualitative data : systematic approaches. Los Angeles Calif.: SAGE; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013 Feb;32(2):207–214. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans A, Banks K, Jennings R, et al. Increasing access to healthful foods: a qualitative study with residents of low-income communities. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015 Jul 27;12(Suppl 1):S5. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-12-S1-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jerant AF, von Friederichs-Fitzwater MM, Moore M. Patients' perceived barriers to active self-management of chronic conditions. Patient Educ Couns. 2005 Jun;57(3):300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eberly MLDMT, Lee T. The Goal Striving Process. In: Locke E, Latham G, editors. New Developments in Goal Setting and Task Performance. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis Group; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Webb TL, Chang B, Benn Y. ‘The Ostrich Problem’: Motivated Avoidance or Rejection of Information About Goal Progress. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2013;7(11):794–807. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ketelaar T, Au WT. The effects of feelings of guilt on the behaviour of uncooperative individuals in repeated social bargaining games: An affect-as-information interpretation of the role of emotion in social interaction. Cognition Emotion. 2003 May;17(3):429–453. doi: 10.1080/02699930143000662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cron WL, Slocum JW, VandeWalle D, Fu QB. The role of goal orientation on negative emotions and goal setting when initial performance falls short of one's performance goal. Hum Perform. 2005;18(1):55–80. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hospers HJ, Kok G, Strecher VJ. Attributions for previous failures and subsequent outcomes in a weight reduction program. Health education quarterly. 1990 Winter;17(4):409–415. doi: 10.1177/109019819001700405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tracy JL, Robins RW. Appraisal antecedents of shame and guilt: Support for a theoretical model. Pers Soc Psychol B. 2006 Oct;32(10):1339–1351. doi: 10.1177/0146167206290212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ilies R, Judge TA. Goal regulation across time: the effects of feedback and affect. J Appl Psychol. 2005 May;90(3):453–467. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forsterling F. Attributional retraining: a review. Psychol Bull. 1985;98(3):495–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perry RP, Hechter FJ, Menec VH, Weinberg LE. Enhancing Achievement-Motivation and Performance in College-Students - an Attributional Retraining Perspective. Res High Educ. 1993 Dec;34(6):687–723. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ilies R, Judge TA, Wagner DT. The Influence of Cognitive and Affective Reactions to Feedback on Subsequent Goals Role of Behavioral Inhibition/Activation. Eur Psychol. 2010;15(2):121–131. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hall NC, Perry RP, Goetz T, Ruthig JC, Stupnisky RH, Newall NE. Attributional retraining and elaborative learning: Improving academic development through writing-based interventions. Learn Individ Differ. 2007;17(3):280–290. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Charlson ME, Boutin-Foster C, Mancuso CA, et al. Randomized controlled trials of positive affect and self-affirmation to facilitate healthy behaviors in patients with cardiopulmonary diseases: rationale, trial design, and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007 Nov;28(6):748–762. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erez A, Isen AM. The influence of positive affect on the components of expectancy motivation. J Appl Psychol. 2002 Dec;87(6):1055–1067. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.6.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steele CM, Spencer SJ, Lynch M. Self-Image Resilience and Dissonance - the Role of Affirmational Resources. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993 Jun;64(6):885–896. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogedegbe GO, Boutin-Foster C, Wells MT, et al. A randomized controlled trial of positive-affect intervention and medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Feb 27;172(4):322–326. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peterson JC, Charlson ME, Hoffman Z, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Positive-Affect Induction to Promote Physical Activity After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Feb 27;172(4):329–336. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duckworth AL, Quinn PD. Development and Validation of the Short Grit Scale (Grit-S) J Pers Assess. 2009;91(2):166–174. doi: 10.1080/00223890802634290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zemack-Rugar Y, Corus C, Brinberg D. The "Response-to-Failure" Scale: Predicting Behavior Following Initial Self-Control Failure. Journal of Marketing Research. 2012 Dec;49(6):996–1014. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4(1):92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McKirnan DJ. The identification of alcohol problems: socioeconomic status differences in social norms and causal attributions. Am J Community Psychol. 1984 Aug;12(4):465–484. doi: 10.1007/BF00896506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Asch DA, Muller RW, Volpp KG. Automated hovering in health care--watching over the 5000 hours. N Engl J Med. 2012 Jul 5;367(1):1–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1203869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Know Your Health Numbers. [Accessed October 12, 2017];2017 Apr 14; http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/More/Diabetes/PreventionTreatmentofDiabetes/Know-Your-Health-Numbers_UCM_313882_Article.jsp#.Wd-OBltSyM8.

- 53.Rimer B, Glanz K. In: Theory at a Glance. National Institutes of Health NCI, editor. Sep, 2005. p. 25. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.