Summary

The main obstacle to HIV eradication is the establishment of a long-term persistent HIV reservoir. Although several therapeutic approaches have been developed to reduce and eventually eliminate the HIV reservoir only a few have achieved promising results. A better knowledge of the mechanisms involved in the establishment and maintenance of HIV reservoir is of utmost relevance for the design of new therapeutic strategies aimed at purging it with the ultimate goal of achieving HIV eradication or alternatively a functional cure. In this regard, it is also important to take a close look into the cellular HIV reservoirs other than resting memory CD4 T-cells with key roles in reservoir maintenance that have been recently described. Unraveling the special characteristics of these HIV cellular compartments could aid us in designing new therapeutic strategies to deplete the latent HIV reservoir.

Keywords: HIV reservoir, resting memory CD4 T cells, T follicular helper cells, Stem cell-like memory T cells, myeloid-derived cells

Introduction

Current data show that over 36.9 million people around the world are living with HIV infection, with 2 million people became newly infected in 20151. Since it first became available in the mid-1990s, cART has improved the lives of HIV-infected people who have access to and can tolerate therapy (currently 20.9 million HIV-infected subjects are receiving ART according to WHO data), greatly increasing the life expectancy, and significantly reducing associated mortality and morbidity2. The cART can effectively block viral replication in the host and reduce the circulating virus to undetectable levels3. However, it cannot completely eliminate the virus from the human body, and viral load rapidly resumes within 2 to 8 weeks after cART discontinuation4–6. Moreover, cART is not able to completely restore the immune hyperactivation7,8 and chronic inflammation7,9,10 caused by high levels of viremia11. This persistent state of activation/inflammation in spite of cART-induced HIV suppression has been associated with the risk of developing cardiovascular, metabolic, and bone disorders12–14.

HIV reservoirs are the primary obstacle impeding the complete eradication of HIV, and they consist of cell types or anatomical sites that allow persistence of replication-competent HIV for prolonged periods of time in patients on optimal cART regimens15. The HIV cellular reservoir comprises cells with HIV-DNA integrated into their genome, but trancriptionally silent, making the virus refractory to cART and to the action of the immune system. Numerous reports have described that the main HIV cellular reservoir is composed of resting CD4+ T-cells16–18. Importantly, replication-competent provirus from the latent reservoir is capable of reigniting new rounds of infection if therapy is interrupted4,5.

Gastrointestinal mucosa19, central nervous system20, lymph nodes21, and genital tract22 have been described as the major anatomical HIV reservoirs15. In many cases, these anatomical sites are inaccessible to cART23 and/or to the effector cells of the immune system24. In these anatomical reservoirs autonomous viral replication can occur, and systemic viral reseeding could emerge. It has been observed that virus evolution and trafficking between tissues compartments continues in patients with undetectable levels of virus in blood21. Thus, immunological and/or pharmacological control of this latent HIV reservoir is necessary to effectively manage HIV without cART. For this reason, in recent years one of the most active areas in HIV research has endeavored to understand the mechanisms involved in the establishment and maintenance of the HIV reservoir.

We will briefly review the most recent advances concerning the establishment and subsequent control of HIV reservoir, with particular emphasis on the main cell populations described as being involved in the maintenance of the HIV reservoir. Although resting memory CD4+ T-cells (Trm) have been the most widely studied, we will focus on two cell subsets hypothesized to play pivotal role in HIV long-term persistence: stem cell-like memory T-cells (Tscm); and T follicular helper cells (Tfh) of germinal center and their counterpart in peripheral blood (peripheral T follicular helper cells, pTfh). In addition, we will also examine other cell types different from T cells that have been proposed as important harboring of the HIV reservoir. Finally, we will also discuss the wide range of therapeutic strategies used to look for the longed HIV eradication.

The establishment of HIV reservoir

Soon after it was demonstrated that cART may not be sufficient to completely cure HIV, a seminal study showed that the latent HIV reservoir is established at a very early stage of the disease, just a few days after the initial infection25. As a result, treatment during primary HIV-1 infection does not block the establishment of a pool of latently infected resting CD4+ T-cells26,27. Several other studies have confirmed these findings, and have shown that very early cART reduces reservoir size25,28–33. Interestingly, in a cohort of patients treated soon after infection and who controlled viremia after cART discontinuation (the so-called “post-treatment HIV controllers”), a markedly lower viral reservoir was observed 31,32. This suggests an interesting link between the reservoir size and the potential control of HIV infection.

The mechanisms involved in the establishment of HIV latency are not completely understood, and several models have been proposed. Viral latency could be established through a mechanism in which activated HIV-1-infected CD4+ T-cells revert to a resting state non-permissive for viral gene expression34. According to a second model, latency would occur with the direct infection of CD4+ T-cells reverting to a G0 resting memory state34. Another model indicates that latency may be established through direct infection of Trm cells35. A recent study by Chavez et al. has shown that all three scenarios could produce latent HIV infection, although the probability of establishing latency could be higher in resting CD4+ T cells, whereas productive infection is more likely to occur in activated cells36.

Cytokines may be an important factor in the establishment of HIV latency. Immunomodulatory cytokines, such as IL-10 and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), play a key role during the immunosuppressive phase of the immune response37,38, and they could contribute to the generation of a pool of long-lived latently infected cells by the reduction of T-cell activation. More recently, it has been demonstrated that IL-2 and IL-7 induce SAMHD1 phosphorylation in primary CD4+ lymphocytes, eliminating SAMHD1 antiviral activity, increasing the infectivity of memory cells, and leading to HIV integration and reservoir replenishment39. In addition, these cytokines are able to partially reactivate the reservoir from central memory CD4+ T-cells through homeostatic proliferation, though they are unable to reduce the reservoir size40,41.

HIV latency is also influenced by the HIV integration site and chromatin state of the HIV promoter. Integration in sites with low transcription42,43, integration in opposite orientation to host genes44, and transcriptional interference with host genes45,46 likely promote latency. Various epigenetic alterations in host cells seem to be involved in the establishment of latency. A study in HIV-infected cells with LTR activity after proviral integration (active HIV replication) revealed acetylation of histone H3 (H3Ac) and trimethylation of histone H3K4 (H3K4me3), both active histone markers, leading to active virus replication. In contrast, trimethylation of histone H3K27 (H3K27me3), a repressive histone marker, was specifically associated with the LTR region in inactive HIV-infected cells, thus inducing latency. This H3K27 trimethylation seems to be catalyzed by the specific methyltransferase polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), a host cell factor involved in the early phase of HIV-1 transcription silencing47. Moreover, a recent paper by Seu et al. demonstrated that stable changes in the signal transduction and transcription factor network of latently infected cells promotes an unresponsive, anergy-like T cell phenotype essential to the ability of HIV-1 to establish and maintain the latent HIV-1 infection48.

It seems clear that the establishment of HIV reservoir is a complex and multifactorial process that takes place very early after HIV infection. While treatment delivered during primary HIV infection is not able to block the establishment of this reservoir, very early initiation of therapy may reduce its size. Unfortunately, the mechanisms involved in the establishment and maintenance of HIV reservoir are not fully understood. Therefore, unraveling these mechanisms is of utmost importance in the effort to design new therapeutic strategies to cure HIV.

HIV cellular reservoirs

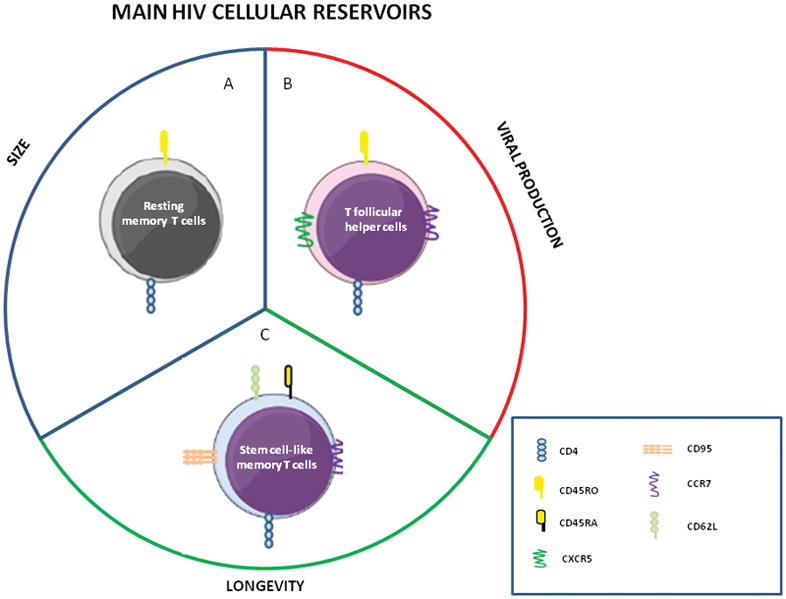

CD4+ T-cells in a resting state are the main cellular component of the latent reservoir. So far the most widely studied population has been the resting memory CD4+ T (Trm) cells. However, in the last few years two new players have become particularly important: stem cell-like memory T (Tscm) cells; and T follicular helper cells (Tfh) of germinal center and their counterpart in peripheral blood (peripheral T follicular helper cells, pTfh) (Figure 1). Moreover, other cell types derived from the myeloid line also seem to have a relevant role as reservoirs of HIV.

Figure 1. Main cellular compartments of HIV reservoir.

Different cell populations of CD4 T cells contribute in a specific way to maintain the viral reservoir. A) Resting memory CD4+ T cells have been considered the major cellular reservoir of quiescent but replication-competent viruses. B) T helper follicular cells have been defined as the main memory CD4+ T cell compartment supporting infection, replication, and production of HIV. C) Stem cell-like memory T cells have been proposed as the most stable and permanent component of the latent HIV reservoir.

Resting memory CD4+ T (Trm) cells

Despite <0.05% of resting CD4+ T cells seem to harbor integrated HIV-DNA in asymptomatic infection49, the major cellular reservoir of quiescent but replication-competent viruses resides in a small pool of this cell type with memory phenotype (Trm cells). It has been showed that CD4+ T-cells with memory phenotype harbored almost the entire replication-competent HIV reservoir (>95%) compared with other CD4+ T-cell subsets50. In fact, in HIV-infected patients on cART, the main source of replication-competent HIV was shown to be the resting CD4+ T-cells with central memory phenotype51. Even, while integrated HIV-DNA reached up to 400 copies/106 resting CD4+ T cells in some patients, the mean frequency in other non-lymphoid cell populations such as macrophages was only 54 copies/106 cells49. These latently infected cells are phenotypically indistinguishable from uninfected cells; hence, host immune response and/or cART cannot effectively kill this population13,26,28,29,52. This latent reservoir in Trm cells is extremely stable, with a mean half-life of around 44 months52,53, requiring approximately 73 years of cART to eradicate a reservoir of 106 cells53.

The main mechanism suggested for the establishment of HIV reservoir in Trm cells is the infection of activated CD4+ T cells surviving the virus cytophatic effect and returning to a resting state54–56. However, several in vitro studies have shown that the direct infection of resting CD4+ T cells may also be involved in the reservoir formation36,57,58. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that infected subjects carry replication-competent HIV in their activated and resting CD4+ T-cell compartments, even when the patient is receiving cART. This suggests continual replenishment of the resting compartment of the reservoir, either by reactivation of infected resting cells or by new rounds of viral infection59,60. Another mechanism that has recently gained relevance in the maintenance of HIV reservoir is the clonal expansion of latently infected cells61–63.

In recent years it has become evident that the mechanisms that promote and sustain the latent infection must be understood. Identification of cellular markers that could unmask the latent infection represents an important step for the development of targeted therapies against the latent HIV reservoir. High expression of the cellular receptor CD2 has been identified in a subset of Trm cells able to produce robust levels of viral particles following ex vivo reactivation64. Also, in successfully treated HIV-patients, central memory CD4+ T-cells expressing CXCR3 and CCR6 surface markers were significantly enriched in integrated HIV-DNA65. In addition, more recently the surface expression of CD32a in CD4+ T cells seems to be associated to enrichment in replication-competent proviruses66.

Nevertheless, other T cell subsets, which have received less attention in research, such as Tscm and Tfh have been identified as potential HIV cellular reservoirs. The unique cellular properties and functional capabilities of these subsets suggest that they could play an important role in the establishment and maintenance of HIV reservoir.

Stem cell-like memory T (Tscm) cells

Tscm cell subset was first described in a murine model as a CD8+ T-cell subset with enhanced self-renewal and multipotency features able to differentiate into all types of T-cell subpopulations67. A possible route was defined by which Tscm CD8+ T-cells are generated through Wnt signaling68, or through the transcription factors T-bet and Eomes, which could cooperate to promote the phenotype of effector/central memory CD8+ T-cell versus the memory stem-like T-cell phenotype69. These cells have been named “memory cells” due to their capacity to differentiate into various memory/effector cell subsets, despite not having the conventional CD45RO+ phenotype of memory T-cells70,71. Subsequently, the Tscm subset was also identified in CD4+ T-cells, exhibiting a phenotype characteristic of naïve T cells (TN) (CD45RO−CCR7+ CD45RA+ CD62L+ CD27+ CD28+ IL7Rα+), though they also express surface markers such as CD95 and CD122 characteristic of memory T-cells (TM), as well as high levels of BCL2, LFA1, CXCR3, and CXCR471. Functionally, Tscm are closer to memory cells, as they present a high response capacity when stimulated by a cognate antigen. Tscm cells represent approximately 2% to 4% of the total CD4+ T-cells in healthy individuals, and an accurate protocol has been designed to isolate and expand Tscm cells from primary samples72.

In recent years, the Tscm CD4+ T cell subpopulation has become an important part of our understanding of HIV pathogenesis and the maintenance of HIV reservoir. A proportion of Tscm cells expresses the main coreceptors for HIV entry, CCR5 and CXCR4, thus rendering them susceptible to HIV infection. Tscm cells seem to be preferentially infected by CCR5-tropic HIV rather than T naïve (TN) cells. Even CXCR4-tropic HIV could infect Tscm cells. However, Tscm cells are less susceptible to HIV infection ex vivo than T central memory (TCM) or T effector memory (TEM) cells73, and show both low sensitivity to cytopathic effects associated with HIV-1 infection and reduced expression of the HIV-1 restriction factors TRIM5α, APOBEC3G, and SAMHD174.

Despite the lower level of integrated HIV-DNA observed in Tscm cells (16 copies/105 cells) compared to TCM (144 copies/105 cells) or TEM (60 copies/105 cells)75 cells, Tscm cells have an important contribution to HIV pathogenesis in the maintenance of viral reservoir. Tscm cells present stem-cell-like properties such as increased proliferative capacity and self-renewal71, and enhanced survival capacity compared to typical memory cells76. A recent study by Jaafoura et al. has showed that after years of successful cART, the latent HIV reservoir may be established in a less differentiated memory CD4+ T-cell subset, such as Tscm cells75. In a group of HIV-patients who received cART for 7 years, the contribution of Tscm cells to the total HIV reservoir was found to be inversely associated with total HIV-1 DNA in the CD4+ T-cell compartment. In fact, a greater contribution of Tscm cells to the HIV reservoir was observed in patients with a smaller HIV reservoir in TCM and TEM cells74. Tscm cells could thus be the most stable and permanent component of the latent HIV reservoir.

The mechanism of establishment of HIV reservoir in Tscm cells seems to be the direct infection since these cells express the HIV correceptors73, thus, HIV could perpetuate itself by infecting this subset76. Moreover, other very important characteristics of this cell population, its long half-life and self-renewal71, could be involved in the establishment and maintenance of HIV reservoir through homeostatic proliferation.

T follicular helper (Tfh) and peripheral Tfh cells

T follicular helper cells (Tfh) are a distinct memory T-cell subset (CD45RO+CXCR5+) involved in B-cell development and antibody production77,78. Tfh are a heterogeneous population with subspecializations and distinct microenvironmental localizations in secondary lymphoid organs79. Although expression of CXCR5 is indispensable for Tfh to enter the B cell follicle, expression of CCR7 could also play a role in helping B cells efficiently produce specific antibodies80. Also, it has been described that the costimulatory molecule ICOS is required for the development and optimum operation of Tfh in vivo81,82. Moreover, IL-21 expression in Tfh is necessary for the formation of the germinal center and isotype switching83. Furthermore, some studies have demonstrated that BCL6 is necessary for Tfh cell differentiation84,85, and PD1 expression could restrain the B-cell-helping function of Tfh to prevent excessive antibody response86.

Recently, it has been found that a peripheral memory CD4+ T-cell subset represents a circulating pool of Tfh cells. This cell subset is called peripheral Tfh (pTfh) cells because it seems to display functional properties similar to the Tfh cells of germinal centers87. Due to the difficulty in accessing the lymph nodes, pTfh cell subset has emerged as an important compartment to be studied for the understanding of HIV infection and persistence. The pTfh cells induce naïve and memory B cells to become Ig-producing cells via ICOS, IL21, and IL10, and secrete CXCL1387. Unlike Tfh cells, however, most pTfh cells do not express activation markers such as ICOS and PD1 at high levels88. Moreover, these cells express the central memory CD4+ T-cell markers, CCR7 and CD62L homing molecules89. Thus, pTfh represent a resting CD4+ T-cell subset (low expression of cell activation markers) with a stable memory cell phenotype88. In addition, pTfh have a high capacity to migrate into secondary lymphoid organs through CCR7 and CD62L expression89. Accurate multiparametric flow cytometric protocols have been developed to define pTfh cells in human blood samples90,91.

Concerning HIV infection, in recent years Tfh cells have taken on a prominent role. A study analyzing four different memory CD4+ T-cell populations from lymph nodes of viremic HIV-infected subjects showed that Tfh cells (defined as CD4+CD45RA-CXCR5+PD1+BCL6+) contained the highest percentage of CD4+ T -cells harboring HIV-DNA and were the most efficient in supporting productive infection in vitro. Thus, Tfh cells were defined as the main memory CD4+ T- cell compartment supporting HIV infection, replication, and production92. Another recent study by Banga et al. analyzed the Tfh subset defined as CD4+CD45RA-CXCR5+PD1+ from lymph nodes of long-term-cART-treated aviremic individuals, and confirmed that the Tfh cells represented the main compartment for persistent transcription and production of replication-competent and infectious HIV93. Moreover, Tfh cells in secondary lymphoid organs lack the expression of SAMHD1 and present a high susceptibility to HIV-1 infection in vitro94. In the simian model (Simian Immunodeficience Virus -SIV-), this cell population represents the main source of virus production in elite controller (EC) animals95.

On the other hand, the counterpart of Tfh cells in blood (pTfh) are highly functional, stimulating the development of neutralizing Abs against HIV88,96 through the production of IL-2196. Furthermore, pTfh cells are significantly reduced during chronic HIV infection but can be significantly recovered after cART initiation97. A very recent study showed that, although less than in Trm cells (1197 DNA copies/million cells) and in non-pTfh cells (989 DNA copies/million cells), pTfh cells contribute significantly to the HIV-DNA content (723 HIV-DNA copies/millions of cells) in patients treated with cART98. In fact, Pallikkuth et al. observed that p24 expression in pTfh cells was higher than in non-pTfh cells in cART-treated individuals99 suggesting that pTfh cells, similar to Tfh cells, may represent an important memory CD4+ T-cell compartment involved in maintenance of replication-competent HIV reservoir, given their ability to actively replicate and produce new infectious HIV virions.

Regarding the establishment of HIV reservoir in these cells it has been proposed some different models. One of them is associated to the high permissiveness of Tfh94,100, and its counterpart in blood (pTfh cells)99, to HIV infection. It has been also proposed that HIV infection would occur in a Tfh precursor subset instead of in Tfh themselves101 taking into account the low CCR5 expression in Tfh cells described by Schaerli et al77. On the other hand, the increased proliferation capacity observed in this cell population92 suggests the participation of the homeostatic proliferation as a mechanism to maintain and expand the infection of Tfh cells.

Monocytes and Macrophages

Monocytes and macrophages are cells of the myeloid lineage with special features that make them a potential HIV reservoir. Monocytes derived from bone marrow circulate in the blood and migrate to tissues differentiating into various types of macrophages102. In 1986, Gartner et al. described the infection and replication of HIV in macrophages, where virus production persisted for at least 40 days103. The expression of CD4 marker and the correceptors CCR5 and CXCR4 by these cells allow the HIV infection104.

Although monocytes rapidly differentiate into macrophages, several studies in peripheral blood have detected HIV in circulating monocytes105–108 with capacity of supporting chronic and highly productive HIV infection109. Moreover, recently it has been observed that a group of monocytes (CD14+CD16+) infected by HIV seems to migrate to central nervous system (CNS) establishing a viral reservoir110. The classical monocytes (CD14+CD16−) that represent ~85% of the monocytes in healthy individuals111,112 seem to be less permissive to HIV infection than CD14+CD16+ monocyte subset112,113. Due to their very low frequency of infection, compared with CD4+ T cells, some studies have fail in detecting HIV-DNA in monocytes114,115. However, other studies in the more permissive monocyte (CD14+CD16+) subset have found HIV-DNA but in lower levels compared to Trm subset of CD4 T cells112. Thus, these cells could represent an important viral reservoir for the ability to disseminate the infection into different tissues and differentiate into macrophages. Actually, HIV-DNA has been detected in macrophages from different organs such as microglial cells116,117, alveolar macrophages118,119, Kupffer cells120 and intestinal macrophages121. Moreover, in the in vitro study of Gartner et al. macrophages were infected by HIV and were able to produce HIV for a long period of time103. Interestingly, in the simian model for the SIV infection, it has been observed the presence of replication-competent SIV in macrophages from brain, blood, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, lungs, and spleen122,123 in ART-suppressed macaques.

Overall, the monocyte-macrophage pool seem to represent a small population in the cellular HIV reservoir, with less than 0.1% of monocytes containing HIV-DNA107 and only 54 per 106 macrophages in lymph node harbouring integrated HIV-DNA49. However, their presence in tissues less accessible to immune system and cART, and their ability to resist the cytopathic effect of HIV124, which seems to be associated to the upregulation of Bim (pro-apoptotic negative regulator of Bcl-2) in latently HIV-infected macrophages125, make these cells an important component of viral reservoir. Even, it has been suggested that macrophages could represent the main source of low-level plasma viremia in patients on cART, since the viral decay in longer-lived cells (1–4 weeks) like monocytes/macrophages is slower than in CD4+ T cells3. Moreover, some studies have shown that macrophages could transmit HIV to target T lymphocytes126,127 in a process involving Siglec-1126 through endocytic compartments in HIV-infected primary macrophages where HIV could survive128.

Dendritic cells and Follicular-dendritic cells

DCs represent an important population of antigen-presenting cells, making these cells a possible target for pathogens like HIV. Primarly, DCs can be classified into myeloid (mDCs) and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs). Patterson et al. showed that both mDCs and pDCs express CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4, the receptors required for HIV infection129, although with differential susceptibility to HIV infection in vitro129,130. In vivo, low level of proviral DNA has been observed in DCs131,132, thus, these cells could play a relevant role in the HIV reservoir. Popov et al. showed that mDCs were able to retain in vitro productive HIV infection of DCs for more than 45 days133. Overall, the most important contribution of DCs to HIV reservoir seems to be the ability to transfer HIV to antigen-specific CD4+ T cells134–136. This seems to be associated to the induction of an important downregulation of SAMHD1 in DCs cocultured with lymphocytes increasing HIV-1 replication in DCs137 what could be further increased by virus-bound host proteins such as LFA-1138.

On the other hand, follicular-DCs are found in B cell follicles in secondary lymphoid organs. Spiegel et al. demonstrated that these FDCs could represent an important role in the HIV reservoir in lymph nodes through mechanisms involving the establishment of HIV-immunocomplexes on cell membranes139 and the ability to internalize HIV in vivo140. In addition, these HIV-immunocomplexes on FDCs have the ability to cause infection of susceptible target cells141 and it was observed that this FDC-trapped HIV was replication competent142. Smith et al. showed that HIV-immunocomplex on human FDCs retained in vitro infectivity for at least 25 days143, suggesting that FDCs could serve as a long-term source of replication-competent virus. Even, a modeling approach suggests that these FDCs could represent the main source of the low-level viremia when HIV is below the limit of detection144.

Megakaryocytes and platelets

It has been proposed that megakaryocytes and platelets could also play a role in the infection and persistence of HIV. Some studies have described productive HIV infection in megakaryocytes145–147, which seems to be associated with the expression in these cells of the CD4 receptor able to bind HIV 148. A later study showed that both CCR5 and CXCR4 HIV isolates are able to infect megakaryocytes149, although only mature megakaryocytic cells seem to be susceptible to HIV infection150. However, it has been observed the induction of apoptosis by HIV gp120, which could limit the potential to establish a latent reservoir in these cells151,152.

Similar to megakaryocytes, it has been observed endocytic vacuoles containing HIV particles close to the plasma membrane in platelets. In this internalization process seems to be involved the DC-SIGN receptor153. Remarkably, a significant level of HIV has been associated to platelets during all stages of HIV infection154. Moreover, Rozmyslowicz et al. observed that platelet- and megakaryocyte-derived microparticles are able to transfer CXCR4 correceptor to other cells, increasing the susceptibility to HIV infection155. Thus, although the special characteristics of platelets prevent the HIV integration and the establishment of a typical HIV reservoir, these cells could play an important role in the spreading of the infection.

Therapeutic strategies for HIV eradication

Although early treatment could reduce the reservoir size28–32, complete viral elimination is not achieved4–6. In recent years several therapeutic approaches have been developed to reduce and eventually eliminate the HIV reservoir. Intensifying the standard cART regimen has been one such approach, based on the assumption that if viral replication is ongoing in spite of cART, the addition of new drugs could have an effect on the low-level viral infection. Intensification with raltegravir showed an impact on the viral life cycle and reduced immune activation in a subset of patients; however, residual viremia was not affected156,157. Thus, drug intensification studies failed to decrease the latent HIV reservoir158–162, suggesting that new infection events were taking place in some patients during cART. However, a very recent study has shown that a combination of maraviroc and raltegravir have a slight impact on proviral HIV-DNA content in gut mucosa163.

Based on knowledge of the mechanisms involved in the maintenance of HIV latency in cellular reservoirs, several studies have employed another approach to target the reservoir: the so-called “shock and kill” strategy specifically designed to purge and eliminate the latent HIV reservoir164. In this strategy, latent HIV is reactivated by LRAs. Spreading of virus from reactivated cells is blocked by cART, and productively infected cells are destroyed by either viral cytopatic effects and/or by the host immune system165. Different LRAs with different mechanisms of action have been assayed in preclinical or clinical trials164–166. Thus far, inhibitors of histone deacetylases (HDAC) have been most widely employed, yielding poor in vivo results167–170; however, a recent in vivo study suggests that romidepsin treatment decreased total HIV-1 DNA171. Other LRAs have been evaluated, albeit with inconclusive results: protein kinase C (PKC) agonists tested ex vivo172–174 and in vivo175, and inhibitors of the DNA methylation tested in vitro176 and ex vivo177.

More recent approaches have been investigated with some interesting results: 1) the in vitro system RNA-guided CRISPR-Cas9 to achieve gene-specific transcriptional activation showed more effective activation of latent virus mediated by activator sgRNA than typical LRAs178,179; 2) In an ex vivo study, BCL-2 antagonist reduced cell-associated HIV DNA when supplied in conjunction with LRAs180; and 3) therapeutic doses of irradiation to activate viral transcription and apoptosis of infected cells have been also suggested181. Of note, the combination therapies with different LRAs have shown the most promising results in in vitro and preclinical studies. PKC agonists in combination with either bromodomain inhibitor JQ1182–184 or HDAC185 induced HIV-1 transcription and release of virus.

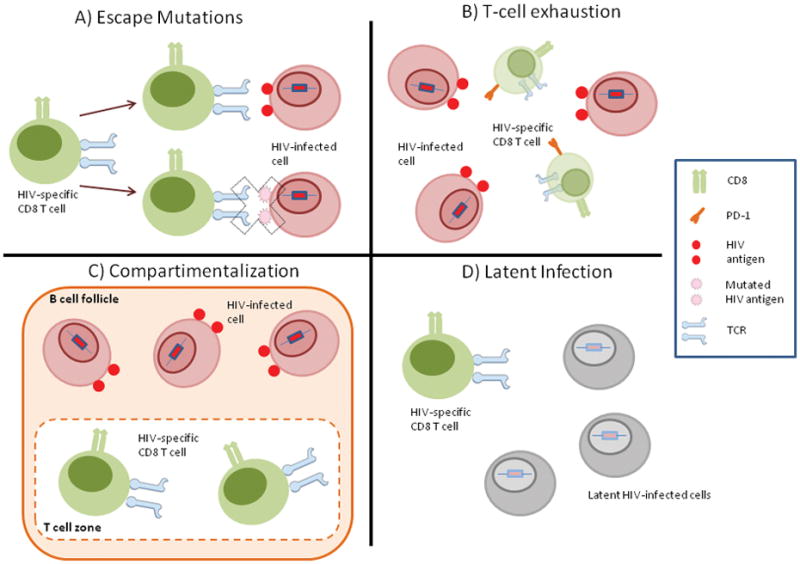

In relation to the “kill” within the “shock and kill” strategy, greater attention has been given to the design of immunotherapeutic interventions in combination with LRAs to purge the HIV reservoir. These approaches include enhancing anti-HIV T-cell immunity and innate immunity and/or virus-specific neutralizing antibodies186. Given the relevance of virus-specific CD8+ T-cells in the infected cells elimination and in the virus replication control, stimulation of adaptive immune response has been explored in combination with LRAs. In in vitro studies, boosting CTL response before using LRAs to reactivate the latent reservoir showed the ability of CD8+ T-cells to efficiently kill reactivated HIV-infected resting CD4+ T-cells187,188. However, in vivo, the existence of provirus with escape mutations in dominant CD8+ T epitopes might preclude the final elimination of reactivated cells189–191. Also, exhaustion and dysfunction192–195, as well as compartimentalization of virus-specific CD8+ T-cells24,196, are additional obstacles to an efficient CD8-mediated eradication of the viral reservoirs (Figure 2). Thus, immunotherapeutic strategies aimed to improve the functionality and/or relocating CD8+ T-cells responses are urgently needed.

Figure 2. Barriers to CTL-mediated HIV eradication.

The figure show the main barriers encountered by HIV-specific CTL response to eliminate HIV-infected cells. A) Escape Mutations: the high ability of HIV to generate escape mutations in epitopes recognized by CTLs. B) T-cell Exhaustion: HIV-induced exhaustion of CTLs renders them unable to eliminate HIV-infected cells. C) Compartimentalization: anatomical compartimentalization in the germinal center of lymph nodes that impedes access of CTLs in the T-cell zone to HIV-infected cells in the B-cell follicle. D) Latent Infection: the establishment of a pool of latently infected T cells that do not express HIV epitopes and thus cannot be recognized by CTLs.

Therapeutic vaccination has been also explored in order to boost HIV-specific T-cell responses with the goal of achieving a functional cure after the administration of LRAs197. Vaccination with the ALVAC-HIV vaccine (modified recombinant canarypox virus expressing the HIV-1 Env and Gag proteins and a synthetic polypeptide that encompasses the CTL epitopes from Nef and Pol proteins) with or without Remune (inactivated gp120-depleted HIV-1) has been associated with a minor loss of CD4+ T-cell counts and delay of viral rebound after cART withdrawal. However, the latent viral reservoir was not impacted198. Even, another phase II study based on ALVAC-HIV vaccine showed that placebo was better than the vaccine, with greater viral rebounds in vaccinees versus placebo recipients199. Also, vaccination with the MVA-B vaccine (modified vaccinia Ankara-based immunogen expressing Env, Gag, Pol, and Nef proteins of HIV-1 clade B) in combination with disulfiram as LRA, showed no impact on either the viral reservoir size or on the rebound of plasma viral load after cART interruption200. Interestingly, although this vaccine was able to boost HIV-specific CD8+ T-cells, immune exhaustion was also increased, showing that vaccination must be aimed not only at boosting preexisting immune responses, but also to increase their functionality201. Eliciting de novo immune responses that target subdominant CD8 T epitopes not presenting escape mutations could represent a promising approach189. Dendritic cells (DCs) will also likely play an important role in enhancing and/or improving virus-specific T-cell responses for HIV reservoir purging. An in vitro study has shown the ability of a DCs vaccine to restore and enhance T-cell reactivity with a polyfunctional response against autologous virus202. Another in vitro study has shown that DCs transduced with a lentiviral vector have induced production of virus from latently infected cells and in parallel have boosted antigen-specific CTLs, providing a strategy to reduce the reservoir size203.

Recently, the role of HIV-1 bNAbs in eradication strategies has received more attention204–207. Passive immunization with VRC01, a potent human mAb targeting the HIV-1 CD4 binding site, on cART-treated individuals with undetectable plasma viremia did not reduce the peripheral blood cell-associated virus reservoir 4 weeks after the second infusion207. On the other hand, in vitro studies have suggested that bNAbs could suppress HIV after reactivation of latently infected cells; however, there was variable sensitivity of virions from the reservoir to neutralization by bNAbs204,205. Moreover, the in vitro ability of antibodies to eliminate reactivated HIV-infected cells through ADCC activity has been evaluated, with not conclusive results205,206. Bruel et al. reported an important ADCC activitity leading to the disappearance of 10% to 50% of Gag+ cells205, whereas Lee et al. reported no significant difference in ADCC responses206. The authors propose that variable susceptibility to ADCC could be the consequence of the high variability seen in the binding of antibodies to the Env epitopes, which could be associated with high differential expression of the HIV-epitopes205,206. However, in order to be effective, ADCC activity will most likely require a potent reactivation, optimal antigen expression, and high antibody potency. Further investigation into this strategy is thus warranted.

Overall, in spite of some promising data, the inconclusive results produced by the aforementioned strategies indicate that the search for approaches that can effectively target the HIV reservoir must still surmount many barriers. It seems clear that single therapies are unlikely to achieve a functional cure or the complete HIV elimination. Combined therapies including the improvement of the immune response (innate and/or adaptive) are an important therapeutic alternative with great potential to impact the latent reservoir in vivo.

Conclusions

Latency remains the most substantial barrier for the HIV eradication. Cellular HIV reservoirs are established soon after infection, and cART in the early phases of the infection seems to control the virus, though it is not able to eliminate the cellular HIV reservoirs. Unfortunately, when applied in clinical practice, new therapeutic strategies have mostly failed to reduce the cellular HIV reservoir size. The heterogeneity of the latent cellular reservoirs may play a role in this regard. In the last few years, Tscm and Tfh CD4-T cell subsets have gained great importance due to their potential contribution to the HIV reservoir. Tscm subset seems to be the subpopulation with the longest half-life whereas Tfh subset has been shown to contain the highest percentage of memory CD4+ T-cells harboring HIV-DNA. The possibility that these cells have different mechanisms that promote HIV latency could add an additional level of complexity when new eradication strategies are designed. Thus, it is of critical importance to continue exploring the mechanisms involved in the establishment and maintenance of the latent reservoir in the different cellular compartments. Understanding the mechanisms maintaining and regulating the latent HIV reservoir hold promise for new eradication strategies.

Search strategy and selection criteria.

Relevant scientific literature was surveyed to review evidence and prepare the manuscript. We searched PubMed for English language papers published between January 1990 and October 2016, and the search was updated before submission (March, 2018). Search terms included: “HIV reservoirs”, “HIV latency”, “HIV cellular reservoirs”, “Latency reversing agents”, “Stem cell-like memory T cells”, “Helper follicular T cells”, Monocytes/Macrophages, Dendritic cells, Follicular dendritic cells, Megacaryocytes/platelets. Two authors (MG and NR) screened abstracts for relevance and reviewed full text articles deemed relevant to topics for manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Funding

We thank Oliver Shaw for assistance in English language editing. This work has been partially funded by the Spanish Carlos III Institute of Health (ISCIII) and FEDER funds (grants: CP14/00198, PI16/01769, RD16/0025/0013, CP17/00179, and RD16/0025/0007); Spanish Secretariat of Science and Innovation and FEDER funds (grant: SAF2015-67334-R). NR and MJB are supported by the Miguel Servet program funded by the Spanish Health Institute Carlos III (grants CP14/00198 and CP17/00179 respectively). MJB is supported by the NIH (grant R21AI118411). MG is co-funded by grant CP14/00198 and Intramural Research Scholarship from IIS-FJD. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ADCC

antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity

- cART

combination antiretroviral therapy

- bNAb

broadly neutralizing antibody

- CTL

cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- DC

dendritic cell

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- EC

elite controller

- FDC

follicular-dendritic cell

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- LRA

latency reversal agent

- LTR

long terminal repeat

- pTfh

peripheral T follicular helper cells

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- sgRNA

single guide RNA

- TCM

T central memory cells

- TEM

T effector memory cells

- TM

memory T-cells

- TN

naïve T-cells

- Tfh

T follicular helper cells

- Trm

resting memory CD4+ T-cells

- Tscm

stem cell-like memory T-cell

- WHO

world health organization

Footnotes

Competing interests

JMB has nothing to disclose; MG has nothing to disclose; MJB has nothing to disclose; NR has nothing to disclose.

Author’s contributions

All authors have participated in the preparation of the manuscript with contributions to draft the manuscript, or providing revisions to content. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. How AIDS changed everything. MDG 6: 15 years, 15 lessons of hope from the AIDS response. 2015 www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/MDG6Report_en.pdf.

- 2.Mocroft A, Ledergerber B, Katlama C, et al. Decline in the AIDS and death rates in the EuroSIDA study: an observational study. Lancet. 2003;362:22–29. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perelson AS, Essunger P, Cao Y, et al. Decay characteristics of HIV-1-infected compartments during combination therapy. Nature. 1997;387:188–191. doi: 10.1038/387188a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calin R, Hamimi C, Lambert-Niclot S, et al. Treatment interruption in chronically HIV-infected patients with an ultralow HIV reservoir. AIDS. 2016;30(5):761–769. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chun TW, Davey RT, Jr, Engel D, Lane HC, Fauci AS. Re-emergence of HIV after stopping therapy. Nature. 1999;401:874–875. doi: 10.1038/44755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stöhr W, Fidler S, McClure M, et al. Duration of HIV-1 viral suppression on cessation of antiretroviral therapy in primary infection correlates with time on therapy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wada NI, Jacobson LP, Margolick JB, et al. The effect of HAART-induced HIV suppression on circulating markers of inflammation and immune activation. AIDS. 2015;29(4):463–471. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vinikoor MJ, Cope A, Gay CL, et al. Antiretroviral therapy initiated during acute HIV infection fails to prevent persistent T-cell activation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(5):505–508. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318285cd33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sereti I, Krebs SJ, Phanuphak N, et al. Persistent, Albeit Reduced, Chronic Inflammation in Persons Starting Antiretroviral Therapy in Acute HIV Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(2):124–131. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendez-Lagares G, Romero-Sanchez MC, Ruiz-Mateos E, et al. Long-term suppressive combined antiretroviral treatment does not normalize the serum level of soluble CD14. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(8):1221–1225. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Appay V, Sauce D. Immune activation and inflammation in HIV-1 infection: causes and consequences. J Pathol. 2008;214(2):231–241. doi: 10.1002/path.2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Funderburg NT, Mehta NN. Lipid Abnormalities and Inflammation in HIV Inflection. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2016;13(4):218–25. doi: 10.1007/s11904-016-0321-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vos AG, Idris NS, Barth RE, et al. Pro-Inflammatory Markers in Relation to Cardiovascular Disease in HIV Infection. A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Abramo A, Zingaropoli MA, Oliva A, et al. Higher Levels of Osteoprotegerin and Immune Activation/Immunosenescence Markers Are Correlated with Concomitant Bone and Endovascular Damage in HIV-Suppressed Patients. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0149601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barton K, Winckelmann A, Palmer S. HIV-1 Reservoirs during Suppressive Therapy. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24:345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chun TW, Stuyver L, Mizell SB, et al. Presence of an inducible HIV-1 latent reservoir during highly active antiretroviral therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13193–13197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong JK, Hezareh M, Günthard HF, et al. Recovery of replication-competent HIV despite prolonged suppression of plasma viremia. Science. 1997;278:1291–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finzi D, Hermankova M, Pierson T, et al. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science. 1997;278:1295–1300. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belmonte L, Olmos M, Fanin A, et al. The intestinal mucosa as a reservoir of HIV-1 infection after successful HAART. AIDS. 2007;21(15):2106–2108. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282efb74b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dahl V, Peterson J, Fuchs D, et al. Low levels of HIV-1 RNA detected in the cerebrospinal fluid after up to 10 years of suppressive therapy are associated with local immune activation. AIDS. 2014;28(15):2251–2258. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorenzo-Redondo R, Fryer HR, Bedford T, et al. Persistent HIV-1 replication maintains the tissue reservoir during therapy. Nature. 2016;530:51–56. doi: 10.1038/nature16933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiscus SA, Cu-Uvin S, Eshete AT, et al. Changes in HIV-1 subtypes B and C genital tract RNA in women and men after initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(2):290–297. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fletcher CV, Staskus K, Wietgrefe SW, et al. Persistent HIV-1 replication is associated with lower antiretroviral drug concentrations in lymphatic tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(6):2307–2312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318249111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connick E, Mattila T, Folkvord JM, et al. CTL fail to accumulate at sites of HIV-1 replication in lymphoid tissue. J Immunol. 2007;178(11):6975–6983. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ananworanich J, Chomont N, Eller LA, et al. HIV DNA Set Point is Rapidly Established in Acute HIV Infection and Dramatically Reduced by Early ART. EBioMedicine. 2016;11:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chun TW, Engel D, Berrey MM, Shea T, Corey L, Fauci AS. Early establishment of a pool of latently infected, resting CD4 (+) T cells during primary HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8869–8873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henrich TJ, Hatano H, Bacon O, et al. HIV-1 persistence following extremely early initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) during acute HIV-1 infection: An observational study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(11):e1002417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strain MC, Little SJ, Daar ES, et al. Effect of treatment, during primary infection, on establishment and clearance of cellular reservoirs of HIV-1. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1410–1418. doi: 10.1086/428777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Archin NM, Vaidya NK, Kuruc JD, et al. Immediate antiviral therapy appears to restrict resting CD4+ cell HIV-1 infection without accelerating the decay of latent infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:9523–9528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120248109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martínez-Bonet M, Puertas MC, Fortuny C, et al. Establishment and Replenishment of the Viral Reservoir in Perinatally HIV-1-infected Children Initiating Very Early Antiretroviral Therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:1169–1178. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sáez-Cirión A, Bacchus C, Hocqueloux L, et al. Post-treatment HIV-1 controllers with a long-term virological remission after the interruption of early initiated antiretroviral therapy ANRS VISCONTI Study. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003211. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chéret A, Bacchus-Souffan C, Avettand-Fenoël V, et al. Combined ART started during acute HIV infection protects central memory CD4+ T cells and can induce remission. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2108–2120. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruner KM, Murray AJ, Pollack RA, et al. Defective proviruses rapidly accumulate during acute HIV-1 infection. Nat Med. 2016;22:1043–1049. doi: 10.1038/nm.4156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen A, Siliciano JD, Pierson TC, Buck CB, Siliciano RF. Establishment of latent HIV-1 infection of resting CD4 (+) T lymphocytes does not require inactivation of Vpr. Virology. 2000;278:227–233. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Unutmaz D, KewalRamani VN, Marmon S, et al. Cytokine signals are sufficient for HIV-1 infection of resting human T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1999;189(11):1735–1746. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chavez L, Calvanese V, Verdin E. HIV Latency Is Established Directly and Early in Both Resting and Activated Primary CD4 T Cells. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004955. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson EB, Brooks DG. The role of IL-10 in regulating immunity to persistent viral infections. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2011;350:39–65. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Travis MA, Sheppard D. TGF-b activation and function in immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:51–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coiras M, Bermejo M, Descours B, et al. IL-7 Induces SAMHD1 Phosphorylation in CD4+ T Lymphocytes, Improving Early Steps of HIV-1 Life Cycle. Cell Rep. 2016;14:2100–2107. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bosque A, Famiglietti M, Weyrich AS, Goulston C, Planelles V. Homeostatic proliferation fails to efficiently reactivate HIV-latently infected central memory CD4+ T cells. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002288. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vandergeeten C, Fromentin R, DaFonseca S, et al. Interleukin-7 promotes HIV persistence during antiretroviral therapy. Blood. 2013;121(21):4321–4329. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-465625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jordan A, Bisgrove D, Verdin E. HIV reproducibly establishes a latent infection after acute infection of T cells in vitro. EMBO J. 2003;22(8):1868–1877. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dieudonné M, Maiuri P, Biancotto C, et al. Transcriptional competence of the integrated HIV-1 provirus at the nuclear periphery. EMBO J. 2009;28(15):2231–2243. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han Y, Lin YB, An W, et al. Orientation-dependent regulation of integrated HIV-1 expression by host gene transcriptional readthrough. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4(2):134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han Y, Lassen K, Monie D, et al. Resting CD4+ T cells from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected individuals carry integrated HIV-1 genomes within actively transcribed host genes. J Virol. 2004;78(12):6122–6133. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6122-6133.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shan L, Yang HC, Rabi SA, et al. Influence of host gene transcription level and orientation on HIV-1 latency in a primary-cell model. J Virol. 2011;85(11):5384–5393. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02536-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsuda Y, Kobayashi-Ishihara M, Fujikawa D, Ishida T, Watanabe T, Yamagishi M. Epigenetic heterogeneity in HIV-1 latency establishment. Sci Rep. 2015;5:7701. doi: 10.1038/srep07701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seu L, Sabbaj S, Duverger A, et al. Stable Phenotypic Changes of the Host T Cells Are Essential to the Long-Term Stability of Latent HIV-1 Infection. J Virol. 2015;89:6656–6672. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00571-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chun TW, Carruth L, Finzi D, et al. Quantification of latent tissue reservoirs and total body viral load in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1997;387(6629):183–188. doi: 10.1038/387183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chomont N, El-Far M, Ancuta P, et al. HIV reservoir size and persistence are driven by T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation. Nat Med. 2009;15:893–900. doi: 10.1038/nm.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soriano-Sarabia N, Bateson RE, Dahl NP, et al. Quantitation of replication-competent HIV-1 in populations of resting CD4+ T cells. J Virol. 2014;88:14070–14077. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01900-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Finzi D, Blankson J, Siliciano JD, et al. Latent infection of CD4+ T cells provides a mechanism for lifelong persistence of HIV-1, even in patients on effective combination therapy. Nat Med. 1999;5:512–517. doi: 10.1038/8394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siliciano JD, Kajdas J, Finzi D, et al. Long-term follow-up studies confirm the stability of the latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells. Nat Med. 2003;9:727–728. doi: 10.1038/nm880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sahu GK, Lee K, Ji J, et al. A novel in vitro system to generate and study latently HIV-infected long-lived normal CD4+ T-lymphocytes. Virology. 2006;355(2):127–37. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang HC, Xing S, Shan L, et al. Small-molecule screening using a human primary cell model of HIV latency identifies compounds that reverse latency without cellular activation. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(11):3473–3486. doi: 10.1172/JCI39199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tyagi M, Pearson RJ, Karn J. Establishment of HIV latency in primary CD4+ cells is due to epigenetic transcriptional silencing and P-TEFb restriction. J Virol. 2010;84(13):6425–6437. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01519-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Swiggard WJ, Baytop C, Yu JJ, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 can establish latent infection in resting CD4+ T cells in the absence of activating stimuli. J Virol. 2005;79(22):14179–14188. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14179-14188.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dai J, Agosto LM, Baytop C, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus integrates directly into naive resting CD4+ T cells but enters naive cells less efficiently than memory cells. J Virol. 2009;83(9):4528–4537. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01910-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chun TW, Nickle DC, Justement JS, et al. HIV-infected individuals receiving effective antiviral therapy for extended periods of time continually replenish their viral reservoir. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3250–3255. doi: 10.1172/JCI26197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murray JM, Zaunders JJ, McBride KL, et al. HIV DNA subspecies persist in both activated and resting memory CD4+ T cells during antiretroviral therapy. J Virol. 2014;88:3516–3526. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03331-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maldarelli F, Wu X, Su L, et al. HIV latency. Specific HIV integration sites are linked to clonal expansion and persistence of infected cells. Science. 2014;345(6193):179–183. doi: 10.1126/science.1254194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wagner TA, McLaughlin S, Garg K, et al. HIV latency. Proliferation of cells with HIV integrated into cancer genes contributes to persistent infection. Science. 2014;345(6196):570–573. doi: 10.1126/science.1256304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hosmane NN, Kwon KJ, Bruner KM, et al. Proliferation of latently infected CD4+ T cells carrying replication-competent HIV-1: Potential role in latent reservoir dynamics. J Exp Med. 2017;214(4):959–972. doi: 10.1084/jem.20170193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iglesias-Ussel M, Vandergeeten C, Marchionni L, Chomont N, Romerio F. High levels of CD2 expression identify HIV-1 latently infected resting memory CD4+ T cells in virally suppressed subjects. J Virol. 2013;87:9148–9158. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01297-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khoury G, Anderson JL, Fromentin R, et al. Persistence of integrated HIV DNA in CXCR3 + CCR6 + memory CD4+ T-cells in HIV-infected individuals on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2016;30:1511–1520. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Descours B, Petitjean G, López-Zaragoza JL, et al. CD32a is a marker of a CD4 T-cell HIV reservoir harbouring replication-competent proviruses. Nature. 2017;543(7646):564–567. doi: 10.1038/nature21710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang Y, Joe G, Hexner E, Zhu J, Emerson SG. Host-reactive CD8+ memory stem cells in graft-versus-host disease. Nat Med. 2005;11:1299–1305. doi: 10.1038/nm1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gattinoni L, Zhong XS, Palmer DC, et al. Wnt signaling arrests effector T cell differentiation and generates CD8+ memory stem cells. Nat Med. 2009;15:808–813. doi: 10.1038/nm.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li G, Yang Q, Zhu Y, et al. T-Bet and Eomes Regulate the Balance between the Effector/Central Memory T Cells versus Memory Stem Like T Cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stemberger C, Neuenhahn M, Gebhardt FE, Schiemann M, Buchholz VR, Busch DH. Stem cell-like plasticity of naïve and distinct memory CD8+ T cell subsets. Semin Immunol. 2009;21:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gattinoni L, Lugli E, Ji Y, et al. A human memory T cell subset with stem cell-like properties. Nat Med. 2011;17:1290–1297. doi: 10.1038/nm.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lugli E, Gattinoni L, Roberto A, et al. Identification, isolation and in vitro expansion of human and nonhuman primate T stem cell memory cells. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:33–42. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tabler CO, Lucera MB, Haqqani AA, et al. CD4+ memory stem cells are infected by HIV-1 in a manner regulated in part by SAMHD1 expression. J Virol. 2014;88:4976–4986. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00324-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Buzon MJ, Sun H, Li C, et al. HIV-1 persistence in CD4+ T cells with stem cell-like properties. Nat Med. 2014;20:139–142. doi: 10.1038/nm.3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jaafoura S, de Goër de Herve MG, Hernandez-Vargas EA, et al. Progressive contraction of the latent HIV reservoir around a core of less-differentiated CD4+ memory T Cells. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5407. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lugli E, Dominguez MH, Gattinoni L, et al. Superior T memory stem cell persistence supports long-lived T cell memory. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:594–599. doi: 10.1172/JCI66327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schaerli P, Willimann K, Lang AB, Lipp M, Loetscher P, Moser B. CXC chemokine receptor 5 expression defines follicular homing T cells with B cell helper function. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1553–1562. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Breitfeld D, Ohl L, Kremmer E, et al. Follicular B helper T cells express CXC chemokine receptor 5, localize to B cell follicles, and support immunoglobulin production. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1545–1552. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kim CH, Rott LS, Clark-Lewis I, Campbell DJ, Wu L, Butcher EC. Subspecialization of CXCR5+ T cells: B helper activity is focused in a germinal center-localized subset of CXCR5+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1373–1381. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.12.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hardtke S, Ohl L, Förster R. Balanced expression of CXCR5 and CCR7 on follicular T helper cells determines their transient positioning to lymph node follicles and is essential for efficient B-cell help. Blood. 2005;106:1924–1931. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Akiba H, Takeda K, Kojima Y, et al. The role of ICOS in the CXCR5+ follicular B helper T cell maintenance in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;175:2340–2348. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rasheed AU, Rahn HP, Sallusto F, Lipp M, Müller G. Follicular B helper T cell activity is confined to CXCR5 (hi) ICOS (hi) CD4 T cells and is independent of CD57 expression. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:1892–1903. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vogelzang A, McGuire HM, Yu D, Sprent J, Mackay CR, King C. A fundamental role for interleukin-21 in the generation of T follicular helper cells. Immunity. 2008;29:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Martinez GJ, et al. Bcl6 mediates the development of T follicular helper cells. Science. 2009;325:1001–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.1176676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yu D, Rao S, Tsai LM, et al. The transcriptional repressor Bcl-6 directs T follicular helper cell lineage commitment. Immunity. 2009;31:457–468. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang C, Hillsamer P, Kim CH. Phenotype, effector function, and tissue localization of PD-1-expressing human follicular helper T cell subsets. BMC Immunol. 2011;12:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-12-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Morita R, Schmitt N, Bentebibel SE, et al. Human blood CXCR5(+)CD4(+) T cells are counterparts of T follicular cells and contain specificsubsets that differentially support antibody secretion. Immunity. 2011;34:108–121. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Locci M, Havenar-Daughton C, Landais E, et al. Human circulating PD-1+ CXCR3− CXCR5+ memory Tfh cells are highly functional and correlate with broadly neutralizing HIV antibody responses. Immunity. 2013;39:758–769. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schmitt N, Bentebibel SE, Ueno H. Phenotype and functions of memory Tfh cells in human blood. Trends Immunol. 2014;35:436–442. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bentebibel SE, Jacquemin C, Schmitt N, Ueno H. Analysis of human blood memory T follicular helper subsets. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1291:187–197. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2498-1_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wei Y, Feng J, Hou Z, Wang XM, Yu D. Flow cytometric analysis of circulating follicular helper T (Tfh) and follicular regulatory T (Tfr) populations in human blood. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1291:199–207. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2498-1_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Perreau M, Savoye AL, De Crignis E, et al. Follicular helper T cells serve as the major CD4 T cell compartment for HIV-1 infection, replication, and production. J Exp Med. 2013;210:143–156. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Banga R, Procopio FA, Noto A, et al. PD-1(+) and follicular helper T cells are responsible for persistent HIV-1 transcription in treated aviremic individuals. Nat Med. 2016;22:754–761. doi: 10.1038/nm.4113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ruffin N, Brezar V, Ayinde D, et al. Low SAMHD1 expression following T-cell activation and proliferation renders CD4+ T cells susceptible to HIV-1. AIDS. 2015;29:519–530. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fukazawa Y, Lum R, Okoye AA, et al. B cell follicle sanctuary permits persistent productive simian immunodeficiency virus infection in elite controllers. Nat Med. 2015;21:132–139. doi: 10.1038/nm.3781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schultz BT, Teigler JE, Pissani F, et al. Circulating HIV-Specific Interleukin-21(+)CD4(+) T Cells Represent Peripheral Tfh Cells with Antigen-Dependent Helper Functions. Immunity. 2016;44:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Boswell KL, Paris R, Boritz E, et al. Loss of circulating CD4 T cells with B cell helper function during chronic HIV infection. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003853. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.García M, Górgolas M, Cabello A, et al. Peripheral T follicular helper Cells Make a Difference in HIV Reservoir Size between Elite Controllers and Patients on Successful cART. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):16799. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17057-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pallikkuth S, Sharkey M, Babic DZ, et al. Peripheral T Follicular Helper Cells Are the Major HIV Reservoir within Central Memory CD4 T Cells in Peripheral Blood from Chronically HIV-Infected Individuals on Combination Antiretroviral Therapy. J Virol. 2015;90:2718–2728. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02883-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kohler SL, Pham MN, Folkvord JM, et al. Germinal Center T Follicular Helper Cells Are Highly Permissive to HIV-1 and Alter Their Phenotype during Virus Replication. J Immunol. 2016;196(6):2711–2722. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Xu Y, Phetsouphanh C, Suzuki K, et al. HIV-1 and SIV Predominantly Use CCR5 Expressed on a Precursor Population to Establish Infection in T Follicular Helper Cells. Front Immunol. 2017;8:376. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Epelman S, Lavine KJ, Randolph GJ. Origin and functions of tissue macrophages. Immunity. 2014;41(1):21–35. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gartner S, Markovits P, Markovitz DM, et al. The role of mononuclear phagocytes in HTLV-III/LAV infection. Science. 1986;233(4760):215–219. doi: 10.1126/science.3014648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lee B, Sharron M, Montaner LJ, et al. Quantification of CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 levels on lymphocyte subsets, dendritic cells, and differentially conditioned monocyte-derived macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(9):5215–5220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.McElrath MJ, Steinman RM, Cohn ZA. Latent HIV-1 infection in enriched populations of blood monocytes and T cells from seropositive patients. J Clin Invest. 1991;87(1):27–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI114981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lambotte O, Taoufik Y, de Goër MG, et al. Detection of infectious HIV in circulating monocytes from patients on prolonged highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;23(2):114–119. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200002010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sonza S, Mutimer HP, Oelrichs R, et al. Monocytes harbour replication-competent, non-latent HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2001;15(1):17–22. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200101050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhu T, Muthui D, Holte S, et al. Evidence for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in vivo in CD14(+) monocytes and its potential role as a source of virus in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Virol. 2002;76(2):707–716. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.2.707-716.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Saini M, Potash MJ. Chronic, highly productive HIV infection in monocytes during supportive culture. Curr HIV Res. 2014;12(5):317–24. doi: 10.2174/1570162x1205141121100659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Veenstra M, León-Rivera R, Li M, et al. Mechanisms of CNS Viral Seeding by HIV+ CD14+ CD16+ Monocytes: Establishment and Reseeding of Viral Reservoirs Contributing to HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders. MBio. 2017;8(5) doi: 10.1128/mBio.01280-17. pii: e01280–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Passlick B, Flieger D, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. Identification and characterization of a novel monocyte subpopulation in human peripheral blood. Blood. 1989;74(7):2527–2534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ellery PJ, Tippett E, Chiu YL, et al. The CD16+ monocyte subset is more permissive to infection and preferentially harbors HIV-1 in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;178(10):6581–6589. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Jaworowski A, Kamwendo DD, Ellery P, et al. CD16+ monocyte subset preferentially harbors HIV-1 and is expanded in pregnant Malawian women with Plasmodium falciparum malaria and HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(1):38–42. doi: 10.1086/518443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Josefsson L, King MS, Makitalo B, et al. Majority of CD4+ T cells from peripheral blood of HIV-1-infected individuals contain only one HIV DNA molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(27):11199–11204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107729108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Honeycutt JB, Wahl A, Baker C, et al. Macrophages sustain HIV replication in vivo independently of T cells. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(4):1353–1366. doi: 10.1172/JCI84456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Trillo-Pazos G, Diamanturos A, Rislove L, et al. Detection of HIV-1 DNA in microglia/macrophages, astrocytes and neurons isolated from brain tissue with HIV-1 encephalitis by laser capture microdissection. Brain Pathol. 2003;13(2):144–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2003.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Churchill MJ, Gorry PR, Cowley D, et al. Use of laser capture microdissection to detect integrated HIV-1 DNA in macrophages and astrocytes from autopsy brain tissues. J Neurovirol. 2006;12(2):146–152. doi: 10.1080/13550280600748946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lebargy F, Branellec A, Deforges L, et al. HIV-1 in human alveolar macrophages from infected patients is latent in vivo but replicates after in vitro stimulation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;10(1):72–78. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.10.1.8292383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cribbs SK, Lennox J, Caliendo AM, et al. Healthy HIV-1-infected individuals on highly active antiretroviral therapy harbor HIV-1 in their alveolar macrophages. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2015;31(1):64–70. doi: 10.1089/aid.2014.0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hufert FT, Schmitz J, Schreiber M, et al. Human Kupffer cells infected with HIV-1 in vivo. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6(7):772–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zalar A, Figueroa MI, Ruibal-Ares B, et al. Macrophage HIV-1 infection in duodenal tissue of patients on long term HAART. Antiviral Res. 2010;87(2):269–271. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Avalos CR, Abreu CM, Queen SE, et al. Brain Macrophages in Simian Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected, Antiretroviral-Suppressed Macaques: a Functional Latent Reservoir. MBio. 2017;8(4) doi: 10.1128/mBio.01186-17. pii: e01186–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Avalos CR, Price SL, Forsyth ER, et al. Quantitation of Productively Infected Monocytes and Macrophages of Simian Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Macaques. J Virol. 2016;90(12):5643–56. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00290-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Swingler S, Mann AM, Zhou J, et al. Apoptotic killing of HIV-1-infected macrophages is subverted by the viral envelope glycoprotein. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3(9):1281–1290. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Castellano P, Prevedel L, Eugenin EA. HIV-infected macrophages and microglia that survive acute infection become viral reservoirs by a mechanism involving Bim. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):12866. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12758-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hammonds JE, Beeman N, Ding L, et al. Siglec-1 initiates formation of the virus-containing compartment and enhances macrophage-to-T cell transmission of HIV-1. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(1):e1006181. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Groot F, Welsch S, Sattentau QJ. Efficient HIV-1 transmission from macrophages to T cells across transient virological synapses. Blood. 2008;111(9):4660–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Jouve M, Sol-Foulon N, Watson S, et al. HIV-1 buds and accumulates in “nonacidic” endosomes of macrophages. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2(2):85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Patterson S, Rae A, Hockey N, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are highly susceptible to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and release infectious virus. J Virol. 2001;75(14):6710–6713. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6710-6713.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Smed-Sörensen A, Loré K, Vasudevan J, et al. Differential susceptibility to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Virol. 2005;79(14):8861–8869. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.8861-8869.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Pope M, Gezelter S, Gallo N, et al. Low levels of HIV-1 infection in cutaneous dendritic cells promote extensive viral replication upon binding to memory CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1995;182(6):2045–2056. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.McIlroy D, Autran B, Cheynier R, et al. Infection frequency of dendritic cells and CD4+ T lymphocytes in spleens of human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients. J Virol. 1995;69(8):4737–4745. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4737-4745.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Popov S, Chenine AL, Gruber A, et al. Long-term productive human immunodeficiency virus infection of CD1a-sorted myeloid dendritic cells. J Virol. 2005;79(1):602–608. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.602-608.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Cameron PU, Freudenthal PS, Barker JM, et al. Dendritic cells exposed to human immunodeficiency virus type-1 transmit a vigorous cytopathic infection to CD4+ T cells. Science. 1992;257(5068):383–387. doi: 10.1126/science.1352913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Loré K, Smed-Sörensen A, Vasudevan J, et al. Myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells transfer HIV-1 preferentially to antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;201(12):2023–2033. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Burleigh L, Lozach PY, Schiffer C, et al. Infection of dendritic cells (DCs), not DC-SIGN-mediated internalization of human immunodeficiency virus, is required for long-term transfer of virus to T cells. J Virol. 2006;80(6):2949–2957. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2949-2957.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Su B, Biedma ME, Lederle A, et al. Dendritic cell-lymphocyte cross talk downregulates host restriction factor SAMHD1 and stimulates HIV-1 replication in dendritic cells. J Virol. 2014;88(9):5109–21. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03057-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Gilbert C, Cantin R, Barat C, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in dendritic cell-T-cell cocultures is increased upon incorporation of host LFA-1 due to higher levels of virus production in immature dendritic cells. J Virol. 2007;81(14):7672–82. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02810-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Spiegel H, Herbst H, Niedobitek G, et al. Follicular dendritic cells are a major reservoir for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in lymphoid tissues facilitating infection of CD4+ T-helper cells. Am J Pathol. 1992;140(1):15–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Heesters BA, Lindqvist M, Vagefi PA, et al. Follicular Dendritic Cells Retain Infectious HIV in Cycling Endosomes. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(12):e1005285. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Heath SL, Tew JG, Tew JG, et al. Follicular dendritic cells and human immunodeficiency virus infectivity. Nature. 1995;377(6551):740–744. doi: 10.1038/377740a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Keele BF, Tazi L, Gartner S, et al. Characterization of the follicular dendritic cell reservoir of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2008;82(11):5548–5561. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00124-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Smith BA, Gartner S, Liu Y, et al. Persistence of infectious HIV on follicular dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166(1):690–696. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Zhang J, Perelson AS. Contribution of follicular dendritic cells to persistent HIV viremia. J Virol. 2013;87(14):7893–901. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00556-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]