To the Editor

Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney (CCSK) comprises approximately 3% of pediatric renal neoplasms, but accounts for a disproportionate number of diagnostically problematic cases1, 2. The classic pattern of CCSK features regular branching fibrovascular septa separating cords and trabeculae of neoplastic cells containing non-overlapping nuclei with fine, evenly dispersed chromatin and inconspicuous cytoplasm. However, CCSK may adopt numerous variant histologic patterns, including epithelioid, spindle cell, myxoid, sclerosing, palisading, and anaplastic. Therefore, CCSK may mimic and be mimicked by every other major pediatric renal neoplasm. Previously, immunohistochemistry has had little role in supporting the diagnosis of CCSK, except to exclude various entities in the differential diagnosis. CCSK is uniformly negative for vascular markers (CD34), neural markers (S100 protein), muscle markers (desmin), and epithelial markers (cytokeratins and epithelial membrane antigen). Cyclin D1, TLE1, SATB2, vimentin, Bcl-2 and CD10 are frequently expressed in CCSK, though none of these is highly specific3–6.

CCSK has recently been shown to harbor internal tandem duplications in the last exon of the BCOR gene in over 90% of cases7–9, with a smaller subset harboring YWHAE-NUTM2B/E10 or BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusions6. All of these genetic abnormalities result in a transcriptional signature characterized by high BCOR mRNA expression11. Nuclear labeling for BCOR by immunohistochemistry (IHC) has been demonstrated to be a highly sensitive marker of CCSK5. All 8 cases of CCSK previously studied by our group demonstrated strong diffuse strong nuclear labeling for BCOR5. Wong et al found nuclear labeling in 73% (8 of 11) CCSK12: the lower sensitivity in the latter study may relate to the different antibody dilution used as well as differences in the immunohistochemical platforms used (which was not specifically stated in the latter study12). Diffuse strong nuclear labeling for BCOR is highly specific for BCOR-related sarcomas of soft tissue, with the one exception being synovial sarcomas; approximately 50% of synovial sarcomas label for BCOR. The specificity of BCOR IHC in the context of pediatric renal neoplasia has not previously been systematically studied.

We therefore evaluated whole tissue sections from 79 neoplasms, including 34 Wilms tumors (including 21 with a stromal component), 17 congenital mesoblastic nephromas (CMN) (2 classic, 10 cellular, 5 mixed), 9 CCSK, 11 metanephric stromal tumors (MST), 4 rhabdoid tumors of the kidney (RTK), 1 renal PNET and 3 sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcomas (SEF). We performed immunohistochemistry for BCOR using clone C-10 (SC-514576; Santa Cruz, Dallas TX) generated against the N-terminus of BCOR at a dilution of 1:150 as done previously5. Tumors were evaluated on the basis of intensity of labeling (strong, moderate, weak, or negative) and the percentage of positive neoplastic cells. Only nuclear labeling was counted, and slides were scored using a 10X eyepiece (100X total magnification). Neoplasms with no labeling were considered negative. Neoplasms with less than 10% labeling of any intensity were considered minimally positive, neoplasms with labeling in 10–50% of neoplastic cells of any intensity were considered focally positive, while neoplasms with strong labeling in greater than 50% of cells were considered diffusely positive.

We found diffuse strong nuclear labeling for BCOR to be both highly sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of CCSK in the setting of pediatric renal neoplasia (Table 1). All 9 CCSK tested in this study (which included none of the eight cases tested previously and found to be diffusely positive5) demonstrated diffuse, strong nuclear labeling for BCOR, ranging from 80–100% of neoplastic cells (Figure 1). New cases tested included a previously reported CCSK with a t(10;17) translocation and YWHAE-NUTM2B fusion10, along with a previously unreported CCSK with a BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusion in a 14 year-old male (Figure 2). Most of the other pediatric renal neoplasms were completely negative for BCOR. A minority showed minimal labeling (<10% of neoplastic cells), and a smaller proportion showed focal labeling (10–50% of neoplastic cells). We noticed in occasional cases of Wilms tumor moderate nuclear labeling of the epithelial component with weak labeling with the adjacent blastema, but no other significant patterns in the minimally to focally positive cases. Of note, of the 9 other pediatric renal neoplasms showing focal positive immunoreactivity, labeling was weak or moderate in all but one, a single primary renal sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma13 that showed strong nuclear labeling in 20% of neoplastic cells.

Table 1.

BCOR IHC in Pediatric Renal Neoplasms

| Completely Negative |

Minimally Positive |

Focally Positive |

Diffusely Positive |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCSK (n=17) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 (100%) |

| Wilms (n=34) | 13 (38%) | 17 (50%) | 4 (12%) | 0 |

| CMN (n=17) | 8 (47%) | 7 (41%) | 2 (12%) | 0 |

| MST (n=11) | 8 (73%) | 3 (27%) | 0 | 0 |

| RT (n=4) | 2 (50%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (25%) | 0 |

| SS (n=7) | 2 (29%) | 1 (14%) | 2 (29%) | 2 (29%) |

| SEF (n=3) | 1 (33%) | 1 (33%) | 1 (33%) | 0 |

| PNET (n=1)* | 1 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

CCSK=clear cell sarcoma of the kidney; CMN=congenital mesoblastic nephroma: MST=metanephric stromal tumor; RT=rhabdoid tumor; SS=synovial sarcoma; SEF=sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma; PNET=primitive neuroectodermal tumor.

only 1 of 9 soft tissue PNET from our prior study showed focal labeling for BCOR5

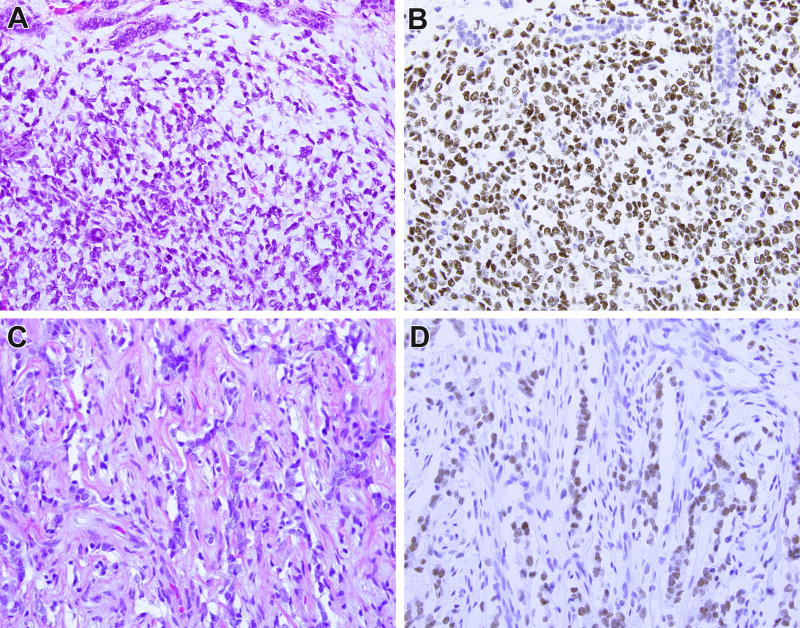

Figure 1.

BCOR immunohistochemistry in clear cell sarcoma of the kidney (CCSK) with BCOR internal tandem duplication (ITD). This CCSK demonstrates entrapped native renal tubules at its periphery, mainly in the upper portions of the field (A). Immunohistochemistry for BCOR demonstrates strong nuclear labeling of the neoplastic cells and absence of labeling of the entrapped renal tubules (B). A treated brain metastasis from a different case of CCSK demonstrates minimal neoplastic cord cells in a background of prominent fibrous septa (C). The neoplastic cord cells but not the supporting elements demonstrate strong nuclear labeling for BCOR (D).

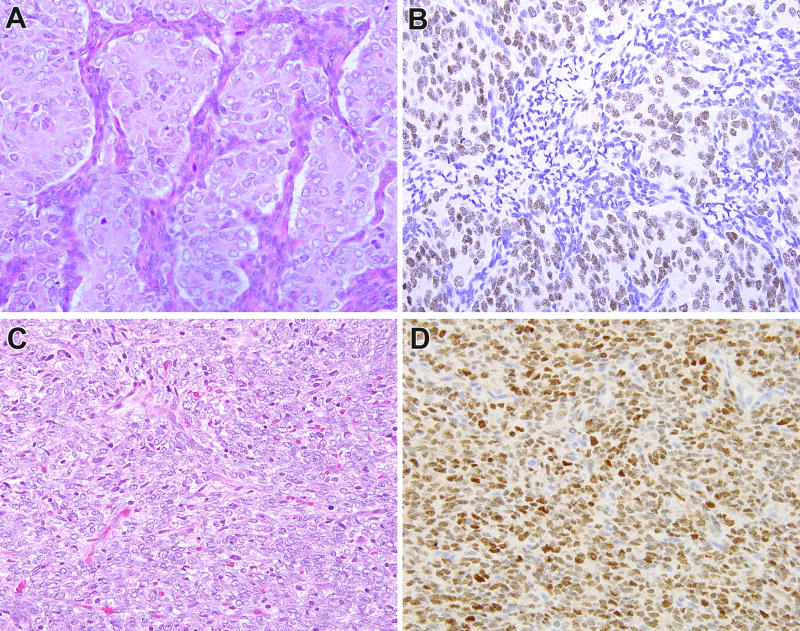

Figure 2.

BCOR immunohistochemistry in clear cell sarcoma of the kidney (CCSK) with less common genetic alterations. This CCSK demonstrated a t(10;17) (q22;p13) translocation resulting in a YWHAE-NUTM2 gene fusion, and demonstrated prominent epithelioid morphology (A). These areas as well as the rest of the neoplasm demonstrates diffuse nuclear labeling for BCOR (B). This CCSK demonstrated a BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusion, and demonstrated predominantly spindle morphology (C). This neoplasm also demonstrated diffuse strong nuclear labeling for BCOR (D).

Therefore, diffuse strong nuclear labeling for BCOR separated CCSK from its major mimickers in the pediatric kidney, including stromal Wilms tumor, cellular congenital mesoblastic nephroma, metanephric stromal tumor, and rhabdoid tumor. While the specificity of BCOR is high, the one known exception remains synovial sarcoma, since as previously shown primary renal synovial sarcomas (like their soft tissue counterparts) also label for BCOR in approximately 50% of cases6, 14, 15. Also, as seen in this study, focal staining in other pediatric renal neoplasms mandates caution when evaluating small biopsies. Moreover, the potential significance of diffuse weak or moderate labeling for BCOR (not encountered in this study) is not clear. Nonetheless, diffuse strong nuclear labeling for BCOR is now the single best immunohistochemical marker for CCSK, demonstrating greater sensitivity and specificity than other previously reported markers such cyclin D1, SATB2, TLE1, CD10, and Bcl-2. Once defined primarily by the absence of immunolabeling for specific lineages (such epithelial, neural, vascular and muscular), CCSK now has its own sensitive and specific diagnostic immunohistochemical marker.

Acknowledgments

We thank Norman Barker MA, MS, RBP for expert photographic assistance. 4-23-18

Disclosures: Supported in part by: P50 CA 140146-01 (CRA), P30-CA008748 (CRA), Cycle for Survival (CRA), Kristin Ann Carr Foundation (CRA), Dahan Translocation Carcinoma Fund (PA), Joey’s Wings (PA)

References

- 1.Argani P, Perlman EJ, Breslow NE, et al. Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney: a review of 351 cases from the National Wilms Tumor Study Group Pathology Center. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:4–18. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gooskens SL, Furtwangler R, Vujanic GM, et al. Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney: a review. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:2219–2226. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mirkovic J, Calicchio M, Fletcher CD, Perez-Atayde AR. Diffuse and strong cyclin D1 immunoreactivity in clear cell sarcoma of the kidney. Histopathology. 2015;67:306–12. doi: 10.1111/his.12641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jet Aw S, Hong Kuick C, Hwee Yong M, et al. Novel Karyotypes and Cyclin D1 Immunoreactivity in Clear Cell Sarcoma of the Kidney. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2015;18:297–304. doi: 10.2350/14-12-1581-OA.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kao YC, Sung YS, Zhang L, Jungbluth AA, Huang SC, Argani P, Agaram NP, Zin A, Alaggio R, Antonescu CR. BCOR Overexpression Is a Highly Sensitive Marker in Round Cell Sarcomas With BCOR Genetic Abnormalities. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:1670–1678. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Argani P, Kao Y-C, Zhang L, Bacchi C, Matoso A, Alaggio R, Epstein JI, Antonescu CR. Primary Renal Sarcomas with BCOR-CCNB3 Gene Fusion: A Report of Two Cases Showing Histologic Overlap with Clear Cell Sarcoma of Kidney, Suggesting Further Link Between BCOR-related Sarcomas of the Kidney and Soft Tissues. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:1702–1712. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ueno-Yokohata H, Okita H, Nakasato K, et al. Consistent in-frame internal tandem duplications of BCOR characterize clear cell sarcoma of the kidney. Nat Genet. 2015;47:861–863. doi: 10.1038/ng.3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Astolfi A, Melchionda F, Perotti D, et al. Whole transcriptome sequencing identifies BCOR internal tandem duplication as a common feature of clear cell sarcoma of the kidney. Oncotarget. 2015;6:40934–40939. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy A, Kumar V, Zorman B, et al. Recurrent internal tandem duplications of BCOR in clear cell sarcoma of the kidney. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8891. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Meara E, Stack D, Lee CH, et al. Characterization of the chromosomal translocation t(10;17)(q22;p13) in clear cell sarcoma of kidney. J Pathol. 2012;227:72–80. doi: 10.1002/path.3985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kao YC, Sung YS, Zhang L, Huang SC, Argani P, Chung CT, et al. Recurrent BCOR Internal Tandem Duplication and YWHAE-NUTM2B Fusions in Soft Tissue Undifferentiated Round Cell Sarcoma of Infancy: Overlapping Genetic Features With Clear Cell Sarcoma of Kidney. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:1009–20. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong MK, Ng CCY, Kuick CH, Aw SJ, Rajasegaran V, Lim JQ, Sudhanshi J, Loh E, Yin M, Ma J, Zhang Z, Iyer P, Loh AHP, Lian DWQ, Wang S, Goh SGH, Lim TH, Lim AST, Ng T, Goytain A, Loh AHL, Tan PH, Teh BT, Chang KTE. Clear cell sarcomas of the kidney are characterised by BCOR gene abnormalities, including exon 15 internal tandem duplications and BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusion. Histopathology. 2018;72:320–329. doi: 10.1111/his.13366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Argani P, Lewin JR, Edmonds P, Netto GJ, Prieto-Granada C, Zhang L, Jungbluth AA, Antonescu CR. Primary Renal Sclerosing Epithelioid Fibrosarcoma: Report of Two Cases with EWSR1-CREB3L1 Gene Fusion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:365–373. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Argani P, Faria PA, Epstein JI, Reuter VE, Perlman EJ, Beckwith JB, Ladanyi M. Primary renal synovial sarcoma: Molecular and morphologic delineation of an entity previously included among embryonal sarcomas of the kidney. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1087–1096. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200008000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kao YC, Sung YS, Zhang L, Kenan S, Singer S, Tap WD, Swanson D, Dickson BC, Antonescu CR. BCOR upregulation in a poorly differentiated synovial sarcoma with SS18L1-SSX1 fusion-A pathologic and molecular pitfall. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2017;56:296–302. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]