Highlights

-

•

We describe a new approach for postpartum or peripartum hemorrhage (PPH) – a major cause of maternal death worldwide.

-

•

In this case we present the first published ultrasound image of chitosan-covered gauze in utero.

-

•

This novel “uterine sandwich” approach can be a useful method for fertility preserving management of PPH.

Keywords: Postpartum hemorrhage, Intrauterine balloon tamponade, Obstetric complications, Chitosan-covered gauze

Abstract

Introduction

Postpartum or peripartum hemorrhage (PPH) is a major cause of maternal death worldwide. Fertility preserving second stage interventions following uterotonic medications may include compression sutures, uterine balloon tamponade and ligation or embolization of arteries.

Presentation of case

We present a case of PPH where a novel “uterine sandwich” approach (combination of chitosan-covered gauze with intrauterine balloon tamponade) was effectively used to stop further blood loss and prevented more invasive second stage interventions. Furthermore, we present the ultrasonographic image of chitosan-covered gauze in the uterine cavity.

Discussion

Chitosan-covered gauze and intrauterine balloon tamponade are complementary in their mechanism of work, the balloon reducing blood flow into the uterus and the chitosan-covered gauze enhancing the coagulation.

Conclusion

This novel “uterine sandwich” approach can be a useful method for fertility preserving management of PPH.

1. Introduction

Postpartum or peripartum hemorrhage (PPH) is a major cause of maternal death in western industrialized countries [1] as well as worldwide [2]. The main reason for PPH is uterine atony followed by placenta retention or abnormally invasive placenta, trauma of the birth canal or coagulopathy [3]. After the administration of uterotonic drugs there are different second line strategies to control blood loss without performing a hysterectomy as a last option to rescue the patient. These are compression sutures (CSU), uterine tamponade, ligation or embolization of arteries [4]. Each second line strategy has its respective risk such as necrosis in the case of CSU [5].

In the following report, we describe a case not described before in which a combination of two measures involving a sandwich technique of chitosan-covered gauze with intrauterine balloon tamponade. The work is reported in line with the SCARE criteria [6].

2. Presentation of case

A 37-year old 2 gravida, 1 para with severe postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) was treated with the novel “uterine sandwich” approach after giving birth to triplets via cesarean section.

At 35 weeks plus 2 days of gestation, a planned cesarean section was performed. Three healthy boys were delivered with birth weights of 2360 g, 2100 g and 1980 g. After delivery, three international units of oxytocin were applied according to the standard protocol to prevent uterine atony. The placenta was delivered without cord traction. Subsequently, Sulprostone was given as continuous infusion. As with Sulprostone IV, prostaglandin was already resorted to and no rectal misoprostol was applied. The uterotomy was closed with a continuous suture and two additional sutures. The total blood loss during the primary operation was estimated at a volume of 500 ml.

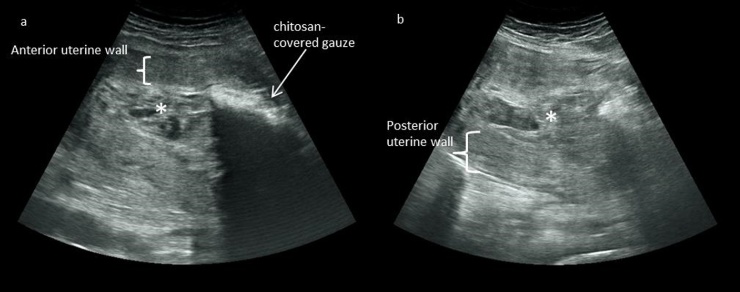

Within 2.5 h, during the postpartum observation period, the uterus became atonic and filled with approximately 2 l of blood. Manual compression and Sulprostone infusion did not sufficiently control the bleeding. The patient was taken to the operation theatre for a vaginal intervention with epidural anesthesia. The clotted blood was manually evacuated from the uterine cavity and curettage under ultrasound guidance was performed. As bleeding continued, surgical measures were discussed. Since it was the first pregnancy of the woman, fertility preserving strategies were preferred. First chitosan-covered gauze (Celox™ gauze, MEDTRADE PRODUCTS LTD. Electra House, Crewe Business Park Crewe, CW1 6GL, UK) was inserted. The patient was informed about the off-label use and gave oral consent. As the bleeding still continued, an intrauterine balloon tamponade (Bakri© Postpartum Balloon, COOK Germany GMBH, Krefelder Straße 745, 41066 Mönchengladbach, Germany) was added into the uterus and filled with 300 ml sodium-chloride as a novel “uterine sandwich” approach. Bleeding stopped after the additional insertion of this balloon. No further invasive surgical techniques such as CSU or ligation of arteries were necessary, bearing less risk for ischemic injury to the uterus. In order to prevent spontaneous expulsion, a vaginal tamponade with two surgical sponges was applied. In total the patient received perioperatively tranexamic acid (TXA), four units of packaged red blood cells and four units of fresh frozen plasma (FFP), with an intraoperative nadir of the hemoglobin of 7.7 g/dl. The intrauterine balloon tamponade was removed after 24 h. Further bleeding was recognized with a drop in hemoglobin value to 5.6 g/dl after 48 h. Clotted blood could be observed in the transabdominal ultrasound in the fundus of the uterus in spite of the chitosan-covered gauze, which presents as a hyperechogenic structure with dorsal acoustic shadow. The patient received two more units of packaged red blood cells. The chitosan-covered gauze was removed after 48 h (Fig. 1). No complications such as a rise in body temperature during the application period of chitosan-covered gauze were observed. After removal, no further significant bleeding occurred. The patient recovered quickly and could be discharged from the hospital on day 9 postpartum.

Fig. 1.

a, b: Transabdominal ultrasonographic view of a chitosan-covered gauze tamponade in utero (a) and uterus after removal of chitosan-covered gauze tamponade (b).

(a): The uterus 48 h after delivery is partially filled with clotted blood in the fundal part of the uterine cavity (*). The chitosan-covered gauze tamponade presents as a hyperechogenic structure with dorsal acoustic shadow in the lower uterine segment. (b): After removal of chitosan-covered gauze tamponade small amount of clotted blood can be seen in the uterine cavity.

3. Discussion

The standard protocol for prevention and treatment of PPH in our hospital follow the actual guidelines of the D-A-CH [7]. Briefly, three international units of oxytocin post-partum are given for any delivery. Escalation of measures follows a stepwise approach. For grade one PPH 3–5 international units of oxytocin or up to 800 μg misoprostol in off-label use are applied. If bleeding still persists, a change to sulprostone if contraction is not sufficient as well as application of tranexamic acid are included in the next step. If bleeding is very likely due to over-distension of the muscle (e.g. in the case of triplets), direct application of sulprostone without trial of rectal application of misoprostol can be performed. In a third step, uterine tamponade is advised. The third step includes CSU, ligation or embolization of arteries. Considering that this is the only measure not preserving fertility; a hysterectomy is performed as a last resort treatment.

In general uterine tamponade is preferred before more invasive surgical measures, as it bears less risk of necrosis for the uterus. Though the mechanism is not yet fully understood, direct compression of the artery in the lower uterine segment or wall confirmation changes due to wall distention are discussed as possible mechanisms [8]. As in the case of atony, relatively small volumes in the balloon suffice and the pressure needed does not exceed the systolic blood flow of the patient. Compression of blood flow in the lower uterine segment seems to be the most important factor in controlling hemorrhaging through balloon tamponade [9,10].

Uterine packing with chitosan-covered gauze for control of postpartum hemorrhage seems to be a safe measure and potentially even lowering hysterectomy rates [11]. Celox™ gauze is a chitosan-covered gauze developed initially to stop severe hemorrhage in the military context [12]. Chitosan stops bleeding by activating tissue factor [13] as well as by interacting directly with erythrocytes and thrombocytes to form a cross-linked barrier clot independent of native factors [14]. Additionally, it is neither allergenic nor exothermic [11].

Several studies have been conducted regarding the use in humans with severe bleeding due to trauma. In a study of 160 patients with penetrating limb trauma, using Celox™ gauze significantly reduced the time to hemostasis and the total blood loss [15].

For control of PPH, different combinations have been proposed. Schmid et al. combined chitosan-covered gauze occasionally with compression sutures, bearing the risk of inclusion of gauze in the stitches necessitating secondary evacuation of uterine cavity [11]. Uterine compression sutures have also been applied in combination with balloon tamponade as a “uterine sandwich” [[16], [17], [18]]. However, necrosis as complication have been reported with this measure [19].

This case report proposes a novel “uterine sandwich” approach: combination of balloon and chitosan-covered gauze in intrauterine packing for PPH. The measures are complementary in their mechanism of work, the balloon reducing blood flow into the uterus and the chitosan-covered gauze enhancing the coagulation with its hemostatic effect on the placental bed.

Celox™ gauze is not yet approved for the use in obstetrics, however its usage has been published before [11]. We present a case were the combination of off-label use of Celox™ gauze and intrauterine balloon tamponade prevented the need of re-laparotomy or other further more invasive second stage interventions. The combination of two less-invasive measures when compared to definite surgical techniques broadens the portfolio of fertility-preserving second stage interventions in PPH. Furthermore, no laparotomy is necessary for this measure. As PPH is a worldwide PPH problem, responsible for maternal morbidity and mortality especially in the developing countries, this fact is very important. Low resource countries sometimes do not have alternative options to hysterectomy such as embolization. Our approach is possible also after vaginal birth in low resource settings.

This is the first report of this novel “uterine sandwich” approach and additionally the first published ultrasound image of chitosan-covered gauze in utero.

Regarding safety of this approach, it has been shown that after the combination of balloon and CSU was applied, women resume normal menstruation [16]. Also after application of chitosan-covered gauze women resume normal menstruation [11]. For the combination of balloon and chitosan-covered gauze, this has not been shown before. In this reported case, the woman was still lactating.

4. Conclusion

This novel “uterine sandwich” approach, chitosan-covered gauze in combination with intrauterine balloon tamponade, can be a useful method for fertility preserving management of PPH.

Prospective and follow-up studies are needed to further validate and confirm the value combined use of intrauterine balloon and chitosan-covered gauze tamponade in the sandwich technique for the treatment of PPH. Furthermore, long-term studies could contribute to the important research and medical techniques regarding future maternal health for example, evaluating the consequences for subsequent pregnancies.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sources of funding

We acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Open Access Publication Fund of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Ethical approval

The patient whose case is presented in this case report has provided signed consent for publication. Ethical approval for publication of this case has been exempted by our institution.

Consent

The patient whose case is presented in this case report has provided signed consent for publication.

Author contribution

Seidel, Vera and Braun, Thorsten contributed equally to the manuscript in writing and data collection.

Weizsäcker, Katharina performed the surgical procedure.

Henrich, Wolfgang contributed mainly to the design of the case report as well as background information.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable for case report.

Guarantor

Vera Seidel.

Acknowledgments

The patient whose case is presented in this case report has provided signed consent for publication.

We thank Dr. Rebecca C. Rancourt for her contribution to this report.

Dr. Seidel is participant in the BIH-Charité Clinical Scientist Program funded by the Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Berlin Institute of Health.

References

- 1.Haeri S., Dildy G.A., 3rd Maternal mortality from hemorrhage. Semin. Perinatol. 2012;36(1):48–55. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Say L. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2014;2(6):e323–e333. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henrich W. Diagnosis and treatment of peripartum bleeding. J. Perinat. Med. 2008;36(6):467–478. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2008.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arulkumaran S., Mavrides E., Penney G. 2011. RCOG Green-Top Guideline No. 52: Prevention and Management of Postpartum Haemorrhage. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seidel V. Vaginal omentum prolapse due to uterine anterior wall necrosis after prophylactic compression suture for postpartum hemorrhage: case report and review of the literature. Case Rep. Perinat. Med. 2017:12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agha R.A. The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlembach D. Management Der postpartalen Blutung: Der «D-A-CH»-Algorithmus. Schweiz Med. Forum. 2013;13(50):1033–1038. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belfort M.A. Intraluminal pressure in a uterine tamponade balloon is curvilinearly related to the volume of fluid infused. Am. J. Perinatol. 2011;28(8):659–666. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1276741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Georgiou C. Intraluminal pressure readings during the establishment of a positive’ tamponade test’ in the management of postpartum haemorrhage. BJOG: An. Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2010;117(3):295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seror J., Allouche C., Elhaik S. Use of Sengstaken-Blakemore tube in massive postpartum hemorrhage: a series of 17 cases. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scan. 2005;84(7):660–664. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmid B.C. Uterine packing with chitosan-covered gauze for control of postpartum hemorrhage. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;209(3):225. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.055. e1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arul G.S., Bowley D.M., DiRusso S. The use of Celox gauze as an adjunct to pelvic packing in otherwise uncontrollable pelvic haemorrhage secondary to penetrating trauma. J. R Army Med. Corps. 2012;158(4):331–333. doi: 10.1136/jramc-158-04-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aktop S. Effects of ankaferd blood stopper and celox on the tissue factor activities of warfarin-treated rats. Clin. Appl. Thromb./Hemost. 2014;20(1):16–21. doi: 10.1177/1076029613490254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kozen B.G. An alternative hemostatic dressing: comparison of CELOX, HemCon, and QuikClot. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2008;15(1):74–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2007.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatamabadi H.R. Celox-coated gauze for the treatment of civilian penetrating trauma: a randomized clinical trial. Trauma. Mon. 2015;20(1):e23862. doi: 10.5812/traumamon.23862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoong W. Application of uterine compression suture in association with intrauterine balloon tamponade (’uterine sandwich’) for postpartum hemorrhage. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scan. 2012;91(1):147–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson W.L., O’Brien J.M. The uterine sandwich for persistent uterine atony: combining the B-Lynch compression suture and an intrauterine Bakri balloon. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007;196(5):e9–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.10.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danso D., Reginald P. Combined B-lynch suture with intrauterine balloon catheter triumphs over massive postpartum haemorrhage. BJOG: Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2002;109(8):963. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lodhi W. Uterine necrosis following application of combined uterine compression suture with intrauterine balloon tamponade. J. Obstet. Gynaecol.: J. Inst. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2012;32(1):30–31. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2011.614972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]