Abstract

Honey bee colony nutritional ecology relies on the acquisition and assimilation of floral resources across a landscape with changing forage conditions. Here, we examined the impact of nutrition and queen age on colony health across extended periods of reduced forage in a southern climate. We measured conventional hive metrics as well as colony-level gene expression of eight immune-related genes and three recently identified homologs of vitellogenin (vg), a storage glycolipoprotein central to colony nutritional state, immunity, oxidative stress resistance and life span regulation. Across three apiary sites, concurrent longitudinal changes in colony-level gene expression and nutritional state reflected the production of diutinus (winter) bees physiologically altered for long-term nutrient storage. Brood production by young queens was significantly greater than that of old queens, and was augmented by feeding colonies supplemental pollen. Expression analyses of recently identified vg homologs (vg-like-A, -B, and -C) revealed distinct patterns that correlated with colony performance, phenology, and immune-related gene transcript levels. Our findings provide new insights into dynamics underlying managed colony performance on a large scale. Colony-level, molecular physiological profiling is a promising approach to effectively identify factors influencing honey bee health in future landscape and nutrition studies.

Introduction

Honey bee (Apis mellifera) colony loss occurs primarily during the winter regardless of climate. Although overwintering in temperate regions has been well studied1–4, relatively little is known of the behavioral, nutritional, and molecular physiological responses from honey bees overwintering in climates of the southern United States. A sizable proportion of US colonies overwinter in warm climates throughout the southern U.S. including southern California, Texas and Florida. In southern climates, shorter and warmer winters can allow for longer growth seasons, but unsustainable brood rearing and foraging activity can also deplete scarce resources during extended periods of forage dearth accompanied by abrupt bouts of colder temperatures. Colony losses are often attributed to poor nutrition, queen failure, compromised immune function, increases in parasites/pathogens, or a combination of these factors5–9.

The western honey bee is adapted to survive seasonal differences in temperature and forage dearth by storing simple sugars in the hive and more complex nutrient stores within the bodies of long-lived workers. This cohort of workers transforms physiologically into a nutrient storage caste referred to as “diutinus” bees10. Following extended forage dearth, the nutrients stored in diutinus bees are used to synthesize food for a new cohort of brood. This colony-level nutritional economy is reliant on the production and conservation of internal storage molecules, predominantly vitellogenin, a nutritionally-regulated protein that is highly expressed during the fall months leading up to winter11–13. Diutinus bees accumulate excess levels of vitellogenin, which increases their life-span and improves their tolerance to starvation and oxidative stress10,14.

To compensate for suboptimal forage conditions and high-density apiaries where natural pollen is scarce, colonies are typically fed artificial (pollen substitute) diets15–18. Some studies have found that artificial diets are inferior to diets containing natural pollen19–21. Compared to natural pollen, artificial diets feature atypical phytochemical and enzymatic profiles that can influence honey bee physiology beyond their primary nutritional roles22–28. One approach to improving honey bee nutrition might incorporate a fraction of natural pollen or components found in a natural diet of pollen and nectar into supplemental feeding regimes. Pollen consumption by workers results in molecular signaling central to honey bee metabolism and aging that is partially mediated by fermentation products produced by hindgut bacteria29–31. The expression of immune genes is also affected by microbiome dynamics and pollen consumption, suggesting that prebiotic properties of pollen could also modulate immunity12,32–34.

A common goal of honey bee research is to effectively distill colony-level factors into simplified metrics that accurately reflect colony performance under various landscape conditions and commercial management settings. For example, intensively cultivated landscapes and migratory management conditions are significantly associated with reduced colony performance and increased levels of oxidative stress6,9,35–39. Forage availability and nutrient balance are fundamental to honey bee processes such as brood production, immune function and overwintering survival12,34,40–44. Additionally, poor nutrition is correlated with a variety of sub-lethal effects including altered immune response and increased susceptibility to pathogens and environmental xenobiotics13,45–48. Nutritional landscape fluctuations and seasonal forage dearth are also associated with increased queen loss7,49,50 highlighting queen age or queen “events” in longitudinal studies51–54. Colonies with young queens also have larger adult populations and increased productivity compared to colonies with older queens50,55–57.

Queen quality and nutrition play an important role in honey bee colony performance and health. As far as we are aware, no large-scale studies have explored relevant management practices during the critical months leading up to winter in a warm southern climate. Here we present a longitudinal study of honey bee colony performance and physiological status in the Imperial Valley of California during a seven month period from July through January. The Imperial Valley represents an agriculturally intensive, warm winter environment with low rainfall and low diversity and abundance of natural forage that necessitates supplemental feeding. We manipulated two factors, queen age and supplemental feed composition, across three distinct apiary sites. We monitored traditional hive metrics of brood production, pollen stores, and pathogen levels as well as nutritional and immune gene expression in pooled worker samples. We tested whether prophylactic queen replacement and supplemental pollen feeding are viable approaches to improve colony performance in a commercial management context. We also hypothesized that a pooled sampling approach would overcome individual variation to more closely reflect colony-level physiological status and establish connections between performance, gene expression and phenology. To further assess the utility of molecular biomarkers at the colony level, we analyzed the expression of recently reported vg-like gene homologs implicated in physiology related to life-span regulation and oxidative stress response58.

Results

Effects of queen age and supplemental pollen feeding

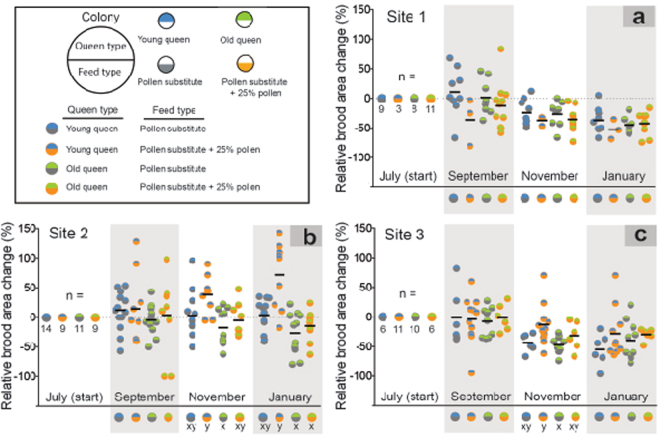

We compared colonies that harbored either a young queen or old queen and were fed either artificial diet containing no pollen or artificial diet containing 25% natural pollen. Surveying 252 colonies across 3 apiaries, queen age had no discernable effect on colony survival (Supplementary Fig. S1). However, surviving colonies with young queens produced significantly more brood overall compared to colonies with old queens (F1,105 = 10.06, P = 0.002; Fig. 1). Brood production by young queens in November and January was 24% and 25% greater than that of old queens, respectively. Supplemental feeding with natural pollen led to a 16.3% increase in brood production compared to exclusively artificial feed, but this increase was not statistically significant (F1,105 = 1.608, P = 0.208, Supplementary Fig. S2). We detected an interaction between diet and evaluation time point on brood production (F2,210 = 3.782, P = 0.024; Supplementary Fig. S2), suggesting that the efficacy of artificial feed formulations are impacted by season-dependent, nutritional landscape dynamics. Consistent with this finding, an interaction between diet and evaluation time point led to detection of increased vg-like-A expression in November in colonies fed pollen (P = 0.023; Supplementary Fig. S3), suggesting that pollen feeding increased the production of vg-like-A in diutinus bees relative to exclusively artificial feed. Besides the aforementioned effect on vg-like-A expression, feed composition did not significantly influence colony-level gene expression (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Colonies that harbored young queens outperformed colonies that harbored old queens with respect to total brood production. Colonies with young queens produced 24% and 25% more brood in November and January, respectively. Values represent the percent change in total brood area relative to July. Red horizontal lines indicate the mean. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences in November and January at α = 0.05.

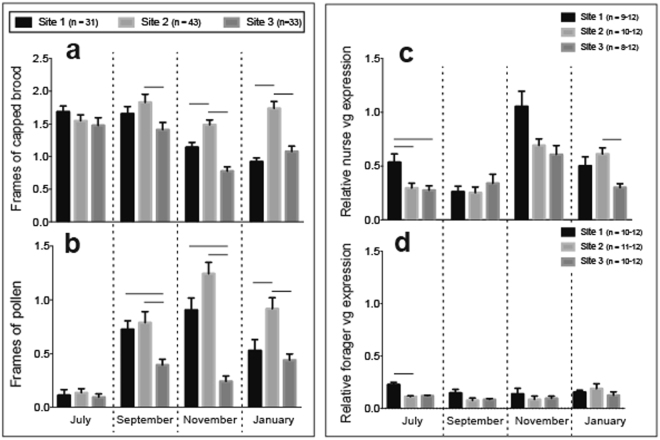

Treatment effects differed by site. No treatment effects were detected at site 1 (P > 0.05; Fig. 2a). At site 2 in November, young queen colonies fed pollen had significantly increased brood areas compared to old queen colonies fed no pollen (X2 = 11.316, df = 3, P = 0.010; Fig. 2b) At site 2 in January, young queen colonies fed pollen produced significantly more brood than old queen colonies fed no pollen and old queen colonies fed pollen (X2 = 17.106, df = 3, P < 0.001; Fig. 2b). At site 3 in November, young queen colonies fed pollen had significantly increased brood production compared to old queen colonies fed no pollen (X2 = 9.145, df = 3, P = 0.027; Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

The effects of queen age and supplemental pollen feeding on colony brood production. Colonies harbored either young queens or old queens and received supplemental feed consisting of either artificial pollen substitute or the same feed containing 25% natural pollen (w/w). Values represent the percent change in brood area relative to July. Black horizontal lines indicate the mean. Within each site and evaluation period, different letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatment combinations at α = 0.05.

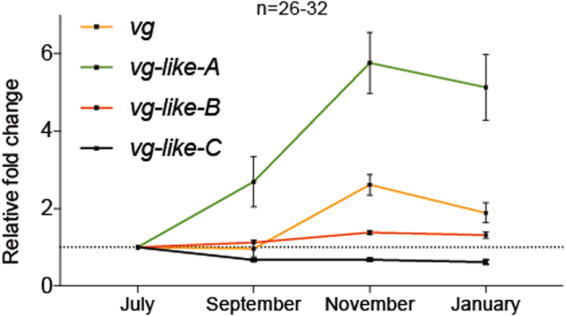

Expression of vitellogenin homologs vg-like-A, -B, and -C

Increased fall vg expression is a characteristic attribute of diutinus bee production. We tested the prediction that vg-like gene transcripts are expressed according to seasonal patterns of diutinus (typically overwintering) bees. Transcript levels of vg-like-A revealed distinct spatiotemporal expression patterns and transcript levels of vg-like-A, -B, and -C were all significantly influenced by evaluation time point (Supplementary Fig. S4). Compared to vg transcript levels, temporal expression differences in vg-like-A were detectable in September. In November, vg-like-A expression increased 5.8-fold in whereas vg increased only 2.6-fold, suggesting that vg-like-A may play an important role in colony-level physiology associated with diutinus worker production (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Fall through winter colony-level expression patterns of vg-like genes. Values represent fold changes relative to July mRNA levels and normalized to actin. Error bars represent standard error (SE).

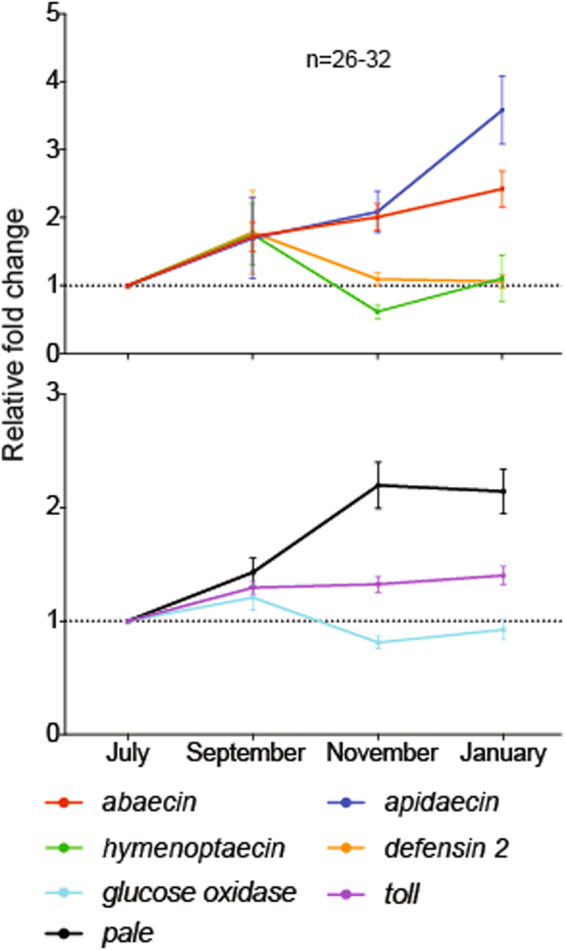

Immune-related gene expression

Colony-level expression analyses revealed significant effects of evaluation time point on transcript levels of the immune-related genes abaecin, apidaecin, hymenoptaecin, defensin 2, glucose oxidase, toll, and pale (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. S5). Relative to July, January expression of the antimicrobial peptides abaecin and apidaeicin increased 2.4- and 3.5-fold, respectively (Fig. 4). Similarly, expression of pale increased approximately 2-fold and expression of toll increased approximately 1.4-fold (Fig. 4). Expression levels of the antimicrobial peptide apidaecin were significantly influenced by site (F2,116 = 3.565, P = 0.031; Supplementary Fig. S6). An interaction between evaluation time point and apiary site led to detection of significantly different transcript levels of glucose oxidase among sites (F6,117 = 4.133, P < 0.001; Supplementary Fig. S6). Expression of pale, a tyrosine hydroxylase involved in melanization and response to bacterial challenge, was significantly influenced by site (F2,117 = 8.748, P < 0.001; Supplementary Fig. S6).

Figure 4.

Fall through winter temporal expression patterns of immune-related genes. Values represent fold changes relative to July mRNA levels.

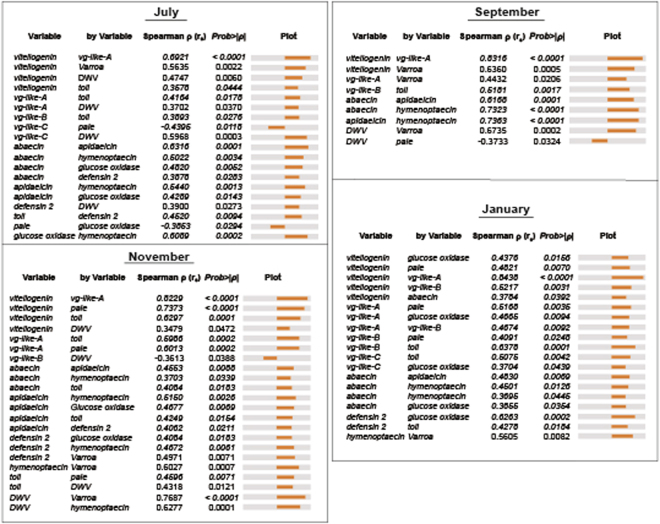

Effects of apiary site on hive performance and vitellogenin expression

From July-January, apiary site had a marked effect on total brood production (F2,104 = 8.354, P < 0.001; Supplementary Fig. S7) and pollen storage. In September, honey bee colonies at site 2 produced significantly more capped brood than site 3 (F2,104 = 13.47, P < 0.001; Fig. 5a). In November and January, colonies at site 2 produced significantly more capped brood relative to both of the other apiary sites (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. S8). In September and November, colonies at site 3 accumulated significantly less pollen than sites 1 and 2 (September: X2 = 9.941, df = 2, P = 0.007 and November: X2 = 40.975, df = 2, P < 0.001; Fig. 5b). In January, colonies at site 2 accumulated significantly more pollen than sites 1 and 3 (X2 = 17.085, df = 2, P < 0.001; Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

The effects of apiary site on honey bee hive performance and colony-level vg expression. (a) Average frames of capped brood per colony measured as whole frame coverage equivalents. (b) Average pollen accumulation measured as whole frame coverage equivalents. (c) Relative vg expression in pooled nurse bee samples collected from inside colony brood nests. (d) Relative vg expression in pooled forager bee samples collected from outside hive entrances. Error bars represent standard error (SE). Horizontal lines above columns indicate statistically significant differences at α = 0.05.

Relative vitellogenin (vg) mRNA levels were measured in separate pools of nurse and forager worker bees from a random subset of colonies at each apiary site. Pooled nurse workers had significantly higher vg transcript levels than pooled forager workers (Fig. 5c,d). Site had a significant effect on vg expression in nurses (F2,116 = 7.542, P < 0.001; Fig. 5c) and foragers (F2,120 = 4.791, P = 0.010; Fig. 5d). Site effects varied by evaluation time point for Vg expression, which could be attributed to environmental fluctuations and pre-winter colony phenology (nurses; F3,116 = 26.9, P < 0.001 and foragers; F3,120 = 3.023, P = 0.032).

Significant correlations were observed between total brood production, pollen stores, and nurse vg expression (Supplementary Fig. S9). The strength and significance of the relationships varied by time. Notably, nurse vg expression in September was positively correlated with pollen stores (rsq = 0.609, P < 0.001) and total brood area (rsq = 0.436, P = 0.018), indicating the potential of Vg as a molecular diagnostic that partially recapitulates standard hive metrics. July brood area was predictive of September brood area (rsq = 0.485, P = 0.006), September pollen stores (rsq = 0.447, P = 0.012), January brood area (rsq = 0.405, P = 0.024) and January pollen stores (rsq = 0.447, P = 0.012). Within-month correlations between brood area and pollen stores were identified in November (rsq = 0.427, P = 0.021) and January (rsq = 0.510, P = 0.003).

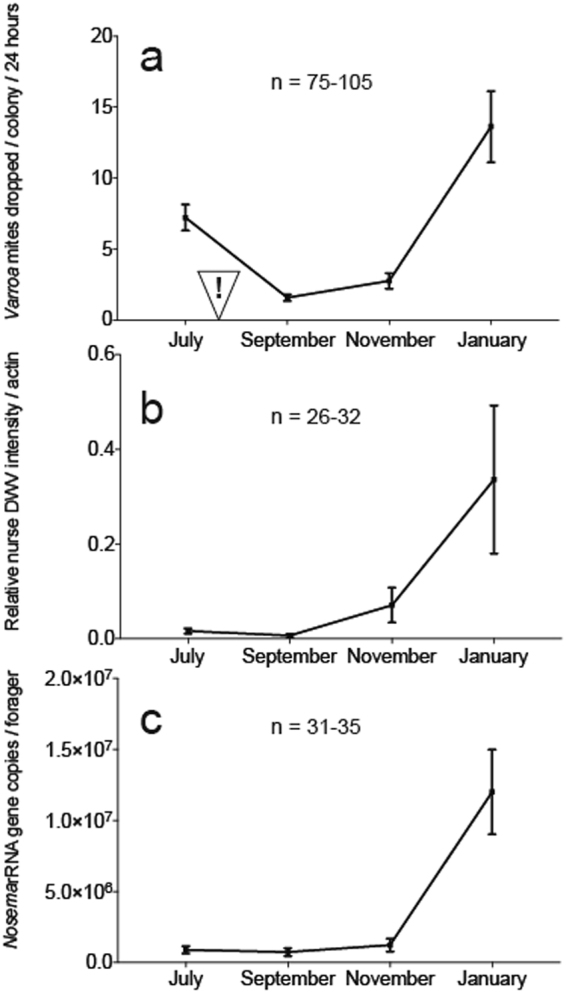

Varroa, deformed wing virus, and Nosema ceranae levels

Varroa, deformed wing virus (DWV), and Nosema levels were monitored throughout the experiment. Significant differences in pathogen levels were observed with respect to evaluation time point. At the start of colony evaluations in July, colonies had significantly higher Varroa levels than in September and November (X2 = 103.369, df = 3, P < 0.001; Fig. 6a) which could be attributed to an acaricide treatment applied in late August. Following the acaricide application, Varroa levels were reduced 4.6-fold in September and began to increase by November although still reduced 2.6-fold from starting levels in July. Overall, deformed wing virus levels in nurse workers were significantly reduced from July to September and were highest in January (X2 = 33.593, df = 3, P < 0.001; Fig. 6b). Both nurse and forager DWV levels mirrored colony Varroa levels (Fig. 6b and Supplemental Fig. S10). From July-November, the prevalence of Nosema infection was below 106 rRNA gene copies per bee in nurse and forager workers. In January, forager Nosema levels reached 107 rRNA gene copies per bee, which was significantly higher than July-November levels (X2 = 48.330, df = 3, P < 0.001; Fig. 6c) and nearly 10-fold higher than nurse levels (Supplemental Fig. S11).

Figure 6.

Varroa, deformed wing virus, and Nosema levels at each apiary site. (a) Varroa levels measured by passive mite drop per hive per 24 hours. A miticide treatment was applied in August and is indicated by (!) (b) Relative deformed wing virus levels in pooled nurse bee samples normalized to host actin and expressed on a log scale. (c) Absolute quantification of Nosema 16S rDNA (rRNA gene) copies in pooled forager samples expressed per bee. Error bars represent standard error (SE).

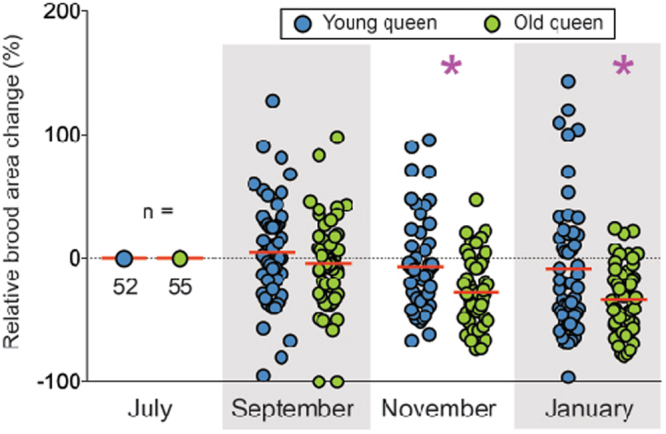

Molecular correlations

Molecular correlations emphasize physiological organization at the colony level and the relative strength of the relationships between nutritional markers (vg and vg-like), immunity, and pathogen levels (Fig. 7). Overall, vg expression was strongly correlated with vg-like-A. Expression of vg-like-a, -b, and -c correlated with immune expression depending on evaluation time point. In July, November, and January, vg-like-a was correlated with toll, which encodes a signal transducing protein involved in immune response and development. In November and January, toll was correlated with antimicrobial peptide gene expression. Transcript levels of the antimicrobial peptides were correlated with each other to varying degrees at each evaluation time point. DWV levels were correlated with colony Varroa infestation levels in September and November. Vg expression was correlated with Varroa infestation levels and DWV titers in July. In September, vg and vg-like-a expression were correlated with Varroa infestation levels.

Figure 7.

Spearman rank correlations for the different molecular markers that were determined significant (P < 0.05) at each evaluation period (July, September, November, and January; n = 26–32).

Discussion

Queen quality and nutrition are critical variables that influence honey bee colony performance and health. There are relatively few studies that quantify colony performance with respect to specific management practices on a large scale and we are unaware of studies that report fall through winter colony-level physiology in a warm southern climate. Our study evaluated the influence of queen age and supplemental pollen feeding at the apiary scale in the Imperial Valley, California. In addition to landscape dynamics, queen quality and age influence colony growth and productivity51,53,54. At two sites in November, colonies with young queens that were fed natural pollen showed significantly improved brood production relative to colonies with old queens that were fed artificial diet. At one site in January, colonies with young queens that were fed natural pollen outperformed colonies with old queens fed either diet. Overall, colonies that harbored young queens produced 24–25% more brood compared to colonies that harbored old queens in fall and winter. Queen reproductive potential is modulated by the rearing environment, aging, and possibly the extended microbiome52,59–62. In the context of this experimental design, our findings suggest that young queens could improve colony brood rearing and that supplemental feeding with natural pollen might further augment brood production, particularly during the fall-winter period when robust diutinus cohorts may be especially important for colony survival.

The increase in brood production from a feeding regime containing 25% natural pollen was not statistically significant despite trending that way in November and January. Limited pollen foraging and pollen stores were observed throughout the experiment, indicating that most hives had at least intermittent access to natural forage that may have diminished the impact of supplemental feeding with natural pollen. We also detected a significant interaction between feeding regimen and evaluation period. These results suggest that natural pollen likely provides essential/critical/important micronutrients or influences host gene expression, and the efficacy of artificial diets may be improved by modification according to spatial and temporal fluctuations in the nutritional landscape. Supplemental feed type did not influence gene expression, except for November transcript levels of vg-like-A, which were significantly increased in colonies fed natural pollen. Considering the role of vg-like-A in winter bee phenotypes, these results suggest that artificial feed containing natural diet components has the potential to improve colony health during overwintering, a period of elevated colony losses63,64.

Our findings revealed site-specific differences in pollen accumulation and brood production, which were recapitulated in nurse vg expression levels. These insights could be applied to commercial management by manipulating the size, location, or feeding regimen of apiaries with reduced colony-level vg expression to improve nutritional conditions at those sites.

The observed differences among apiaries suggest the importance of landscape variation in studies of colony health. Although we observed little indication of disease at any of the 3 sites, records of dysentery in the Imperial Valley indicate site-specific disease outbreaks (Bryan Ashurst pers. Comm.) that may in part explain differences by site, particularly differential immune gene expression.

The combined results indicate the production of diutinus bees in a warm southern climate as evidenced by a mean reduction in brood rearing and a net increase in nurse vg expression leading up to winter. Honey bee vg acts as a storage molecule and precursor to proteinaceous secretions produced by nurse bees to rear brood65–67. This ubiquitous glycolipoprotein also plays a crucial role in mediating the stresses incurred during overwintering. Vg has undergone significant past and ongoing stretches of adaptive evolution with a large proportion of amino acid changes fixed by positive selection68. The vg homologs vg-like-A, -B, and -C were recently identified in all sequenced hymenopteran genomes and may have arisen from ancient gene duplications of vg69. Vg-like-A shares close structural and functional similarities with vg69. We identified temporal expression patterns that were consistent with the role of vg and vg-like-A in life span regulation and winter bee phenotypes10,14, but vg-like-A exhibited a sizeable fold-change earlier in the season and a larger relative response throughout. Moreover, transcript levels of both vg and vg-like-A were influenced by site, but subtle differences in their responses over time suggest they may be differentially regulated. These differences suggest that vg-like-A shows promise as an additional colony-level biomarker that may provide complementary information to vg when studying colonies across a dynamic nutritional landscape. Vg-like-B responds to oxidative stress and is linked to over-wintering phenotypes but to a lesser extent than vg-like-A58. The function of vg-like-C is currently unknown but its expression patterns are consistent with functional divergence from vg and the other homologs. We provide the first report of colony-level expression of vg-like genes in the honey bee. We determined that the relative expression levels of vg-like-a, -b, and -c in pooled nurse samples were similar to those previously reported in individual bee fat bodies58 and ants69. Together with vg, these homologs show promise as prototypical biomarkers that correlate with nutritional and immunological status.

Immunity is intimately tied to nutritional status, and malnourished individuals are more susceptible to disease. In northern climates overwintering success relies on consistent cold temperatures that keep bees in the hive in a state of nutrient conservation. Although simple sugars are metabolized for heat, the proteins and lipids needed to rear brood in the spring are conserved. Consistent with this conservation hypothesis, overwintering in northern climates is associated with reduced immune gene expression at the colony level2. In contrast, we detected increased or stable immune expression, a significant energy investment for bees70,71. This fundamental difference suggests a colony level expenditure of proteins that may represent a net negative cost to colonies overwintering in southern climates. An additional related cost, pollen species diversity in the Imperial Valley is likely reduced compared to areas with greater average rainfall and less agricultural intensity37. Pollen species diversity is positively correlated with increased nutritional quality6. The continuous foraging effort we documented throughout the winter months likely results in the collection of incomplete pollen nutrition, compounding the cost associated with continuous immune expression.

Conclusion

Here we provide the first comprehensive assessment of overwintering honey bee colonies in a southern climate. Our results detail a critical point in the bee life cycle with strong selection on colony survival. We recorded a 45% colony loss leading up to and concurrent with the seasonal production of diutinus bees. In northern climates, colonies typically revert to a broodless state. In contrast, we recorded no surviving colonies that were broodless, and activity outside the hive continued throughout the winter. Thus, colony behavior and physiology that accompany overwintering can take multiple forms depending on climate but retain signatures of honey bee life history traits as evidenced by group-level temporal expression patterns of vitellogenin.

Effective, high-throughput characterization of colony physiology can inform management decisions and land use practices that lead to improved honey bee health and performance37,44,72. To realize this goal on a commercial scale, colony-level molecular biomarkers require further development and characterization to identify the most sensitive and therefore useful targets. It is especially important to investigate their variation across a range of seasonal, geographic, and management contexts. Physiological measures of single adult individuals can fluctuate dramatically due to available forage, supplemental nutrition, seasonal colony demography, and pathogen loads38. Here we used a colony-level approach to integrate standard methods of hive evaluation with molecular measures of physiology. The honey bee colony is an adaptively organized entity that acquires and assimilates nutrition via age-based distribution of labor. To obtain molecular signal, we field-collected separate pools of foragers (n = 25) and nurses (n = 50) based on the robust spatial variation in worker tasks. We observed markedly higher vg expression in nurses compared to foragers, a well-established pattern based on studies using individual bees11,73,74. These differences verify the use of a pooled sampling approach to measure colony-level physiology in large field studies.

Methods

Experimental setup and colony management

In March 2016, two hundred and fifty two commercial colonies were established from splits of large, healthy parent colonies sourced from Ashurst Bee Co. Inc. (Westmoorland, CA), which managed all colonies in this study. Colonies were distributed across three sites (Supplementary Figs S12 and S13): Site 1 (Best 115 E & W, 33°01′′38.8′′N 115°31′07.8′′W), Site 2 (Young and River, 33°07′58.8′′N 115°34′05.3′′W), and Site 3 (Jacobsen 111, 33°04′30.5′′N 115°31′14.9′′W). Half of the colonies were requeened with a new Italian queen while half of the colonies retained an Italian queen from the same commercial breeding source that had spent a year in a commercially managed colony. At the start of colony evaluations in July 2016, these young queens were approximately 4 months old and old queens were approximately 16 months old. Colonies were also assigned feeding regimes consisting of patties made either entirely from artificial pollen substitute or from a mixture of substitute plus 25% dried natural pollen. This natural pollen consisted of a 1:1 (w/w) mix of a commercially available corbicular pollen source (Great Lakes Pollen Mix, Great Lakes Bee Supply, Galesburg, MI, USA) and almond pollen collected from pollen traps, vacuum sealed, and stored at −20 °C by USDA-ARS personnel. Feeding treatments were applied to colonies approximately every 21 days.

Colonies were evaluated in July, September, and November 2016, and in January 2017. Evaluations consisted of inspecting each frame and recording the area covered by sealed brood, open brood, and stored pollen. Frames were scored as 1/8, 1/4, 1/2, 3/4, or full (1) covered by each component by the same two researchers throughout the study. The researchers who performed frame scoring were calibrated against each other to reduce variance. These data were summed and expressed as frames of brood or pollen per colony. In January 2017, a total of 107 colonies had survived across all three sites and treatment combinations (see Supplementary Table S1 for details).

A representative subset of 12 colonies per site (36 total hives) were further sampled for molecular analyses at each time point. Pooled samples of two distinct groups of worker bees were collected based on the association between spatial variation in colony tasks and temporal polyethism75–77. Incoming forager and guard bees were collected by vacuum aspiration from hive entrances to represent a cohort of older workers78. Brood nest nurse bees were collected from the center of a healthy brood frame to represent a cohort of younger workers engaged in nutritional assimilation and brood rearing. All bees were sampled into 50 ml conical tubes, immediately frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80 °C for further processing (Supplementary Fig. S14).

Nucleic acid extractions

Separate pools of 25 forager bees and 50 nurse bees were homogenized in lysis buffer (1.2 M guanidine thiocyanate, 0.6 M ammonium thiocyanate) using a rotary homogenizer at a volume of 0.5 ml lysis buffer per bee. One milliliter of each homogenate was added to a 2 ml bead-beating tube containing 0.2 g of 0.1 mm silica beads, immediately frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80 °C until nucleic acid extractions. Prior to extraction, the samples were thawed at 60 °C for 5 minutes, bead beaten for a total of 2 min in 30 s intervals and centrifuged to recover the supernatant. The RNA fraction was purified from 300 μl of the resulting supernatant using a GeneJet RNA Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacture’s instructions. The DNA fraction was purified from 300 μl of the resulting supernatant using a GeneJet DNA Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for Gram-positive bacteria.

Gene expression analyses

Vitellogenin (vg), vg-like-A, vg-like-B, and vg-like-C, abaecin, apidaecin, hymenoptaecin, defensin 2, glucose oxidase, toll, and pale mRNA levels were measured by quantitative PCR (qPCR) and cDNA template generated from the purified RNA fraction of pooled bee samples. cDNA synthesis was carried out using a RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). PCR reactions were performed in triplicate as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 minutes; 40 cycles with denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s; and a primer-pair-specific annealing and extension temperature (Supplementary Table S2) for 30 seconds. The reactions were carried out using iTaqTM Universal SYBR® Green Supermix (Biorad) in triplicate on an CFX96TM Real-Time PCR Detection System (Biorad). To confirm the absence of contaminating genomic DNA and primer dimers in the qPCR assay, we monitored amplification and melting curves in negative controls consisting of DNase-treated total RNA without reverse transcriptase. Relative gene expression was determined based on standardized Ct values (Δ Ct)79 using actin as a reference gene.

Quantification of Varroa, deformed wing virus, and Nosema ceranae levels

The prevalence of infection by the microsporidian parasite N. ceranae was measured by qPCR using the DNA fraction of pooled bee samples as template. A standard curve was generated using serial dilutions of a plasmid standard containing a 104 base pair product of the N. ceranae ribosomal rRNA gene (Bourgeois et al., 2010). PCR reactions were performed using gene-specific primers (Online Resource 1 Table S1) as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 minutes; 40 cycles with denaturation at 95 C for 15 s; and a combined annealing and extension step at 58 °C for 30 seconds. The reactions were carried out using iTaqTM Universal SYBR® Green Supermix (Biorad) in triplicate on an CFX96TM Real-Time PCR Detection System (Biorad). Sample Cq values were transformed using the linear equation obtained from a logarithmic standard curve of 2 × 103 to 2 × 108 copies of the N. ceranae rDNA template. Standard curve efficiencies ranged from 92–101% with R2 between 0.988–0.999. The qPCR results were expressed as the number of N. ceranae rRNA gene copies per bee after adjusting the values to account for sample volumes. Samples with copy amounts below the range of detection of the standard curve were assigned a value of 104, corresponding to the lower limit of detection after adjustment for volume.

DWV titers were measured by qPCR using cDNA template generated from the purified RNA fraction of pooled bee homogenates80,81. Relative viral levels were determined based on standardized Ct values (Δ Ct)79 using DWV primers (Supplementary Table S1) and actin as a reference gene.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted in JMP v11 and Prism v7. Dependent variables were evaluated for normality using fit statistics and probability plots. Variables with deviations from normality were re-evaluated after transformation. The effects of queen age, supplemental feeding, and apiary site on brood production over time were analyzed by two-way repeated measures ANOVA and post-hoc comparisons were conducted using pairwise t-tests with Bonferroni adjustments. Pollen stores and treatment combination effects were analyzed at each site and evaluation period by Kruskal-Wallis (K-W) test and post hoc contrasts were conducted using pairwise Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon tests with Bonferroni adjustments. The effects of apiary site and evaluation period on gene expression were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and post-hoc comparisons were conducted using pairwise t-tests with Bonferroni adjustments.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the ARS-USDA, research plan 501-2022-050 017. The USDA is an equal opportunity employer and provider.

Author Contributions

V.A.R., B.M.M. and K.E.A. designed and conceived the experiments, V.A.R., B.M.M., A.S.F., D.C.C. and M.J.C., performed the experiments, V.A.R. and B.M.M. analyzed the data, V.A.R. and K.E.A. wrote the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-28732-z.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Vincent A. Ricigliano, Email: Vincent.Ricigliano@ARS.USDA.gov

Kirk E. Anderson, Email: Kirk.Anderson@ARS.USDA.GOV

References

- 1.Mattila HR, Harris JL, Otis GW. Timing of production of winter bees in honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies. Insect. Soc. 2001;48:88–93. doi: 10.1007/PL00001764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinmann N, Corona M, Neumann P, Dainat B. Overwintering Is Associated with Reduced Expression of Immune Genes and Higher Susceptibility to Virus Infection in Honey Bees. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0129956–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smedal B, Brynem M, Kreibich CD, Amdam GV. Brood pheromone suppresses physiology of extreme longevity in honeybees (Apis mellifera) Journal of Experimental Biology. 2009;212:3795–3801. doi: 10.1242/jeb.035063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guzmán-Novoa E, et al. Varroa destructoris the main culprit for the death and reduced populations of overwintered honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies in Ontario, Canada. Apidologie. 2010;41:443–450. doi: 10.1051/apido/2009076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhruba N. Nutritional stress due to habitat loss may explain recent honeybee colony collapses. Biological Conservation. 2009;142:2369–2372. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2009.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallant AL, Euliss NH, Browning Z. Mapping Large-Area Landscape Suitability for Honey Bees to Assess the Influence of Land-Use Change on Sustainability of National Pollination Services. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e99268–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.vanEngelsdorp D, Hayes J, Underwood RM, Pettis J. A Survey of Honey Bee Colony Losses in the U.S., Fall 2007 to Spring 2008. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e4071–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.vanEngelsdorp D, Hayes J, Jr., Underwood RM, Pettis JS. A survey of honey bee colony losses in the United States, fall 2008 to spring 2009. Journal of Apicultural Research. 2015;49:7–14. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.49.1.03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simone-Finstrom, M. et al. Migratory management and environmental conditions affect lifespan and oxidative stress in honey bees. Sci Rep 1–10, 10.1038/srep32023 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Münch D, Kreibich CD, Amdam GV. Aging and its modulation in a long-lived worker caste of the honey bee. J. Exp. Biol. 2013;216:1638–1649. doi: 10.1242/jeb.078915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amdam GV, Norberg K, Fondrk MK, Page RE. Reproductive ground plan may mediate colony-level selection effects on individual foraging behavior in honey bees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101:11350–11355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403073101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alaux C, Dantec C, Parrinello H, Le Conte Y. Nutrigenomics in honey bees: digital gene expression analysis of pollen’s nutritive effects on healthy and varroa-parasitized bees. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:496. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Pasquale G, et al. Influence of Pollen Nutrition on Honey Bee Health: Do Pollen Quality and Diversity Matter? PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e72016–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Münch D, Amdam GV. The curious case of aging plasticity in honey bees. FEBS Letters. 2010;584:2496–2503. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mattila HR, Otis GW. Influence of pollen diet in spring on development of honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) colonies. J. Econ. Entomol. 2006;99:604–613. doi: 10.1093/jee/99.3.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Jong D, da Silva EJ, Kevan PG, Atkinson JL. Pollen substitutes increase honey bee haemolymph protein levels as much as or more than does pollen. Journal of Apicultural Research. 2015;48:34–37. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.48.1.08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeGrandi-Hoffman G, et al. Comparisons of pollen substitute diets for honey bees: consumption rates by colonies and effects on brood and adult populations. Journal of Apicultural Research. 2008;47:265–270. doi: 10.1080/00218839.2008.11101473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Standifer LN, Macdonald RH, Levin MD. Influence of the Quality of Protein in Pollens and of a Pollen Substitute on the Development of the Hypopharyngeal Glands of Honey Bees1,2,3. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 1970;63:909–910. doi: 10.1093/aesa/63.3.909. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeGrandi-Hoffman G, et al. Honey bee colonies provided with natural forage have lower pathogen loads and higher overwinter survival than those fed protein supplements. Apidologie. 2015;47:186–196. doi: 10.1007/s13592-015-0386-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Ghamdi AA, Al-Khaibari AM, Omar MO. Consumption rate of some proteinic diets affecting hypopharyngeal glands development in honeybee workers. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2011;18:73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeGrandi-Hoffman G, Chen Y, Huang E, Huang MH. The effect of diet on protein concentration, hypopharyngeal gland development and virus load in worker honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) J Insect Physiol. 2010;56:1184–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mao W, Schuler MA, Berenbaum MR. Honey constituents up-regulate detoxification and immunity genes in the western honey bee Apis mellifera. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:8842–8846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303884110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pyrzynska K, Biesaga M. Analysis of phenolic acids and flavonoids in honey. Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 2009;28:893–902. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2009.03.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mao W, Schuler MA, Berenbaum MR. A dietary phytochemical alters caste-associated gene expression in honey bees. Science Advances. 2015;1:e1500795–e1500795. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ricigliano VA, et al. The impact of pollen consumption on honey bee (Apis mellifera) digestive physiology and carbohydrate metabolism. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2017;96:e21406–14. doi: 10.1002/arch.21406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wheeler MM, Robinson GE. Diet-dependent gene expression in honey bees: honey vs. sucrose or high fructose corn syrup. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5726. doi: 10.1038/srep05726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grogan DE, Hunt JH. Pollen proteases: their potential role in insect digestion. Insect Biochemistry. 1979;9:309–313. doi: 10.1016/0020-1790(79)90011-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson MB, Spivak M, Hegeman AD, Rendahl A, Cohen JD. Metabolomics Reveals the Origins of Antimicrobial Plant Resins Collected by Honey Bees. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e77512–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee FJ, Rusch DB, Stewart FJ, Mattila HR, Newton ILG. Saccharide breakdown and fermentation by the honey bee gut microbiome. Environmental Microbiology. 2014;17:796–815. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engel, P. & Martinson, V. G. Functional diversity within the simple gut microbiota of the honey bee. In 10.1073/pnas.1202970109/-/DCSupplemental (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Zheng H, et al. Metabolism of Toxic Sugars by Strains of the Bee Gut Symbiont Gilliamella apicola. mBio. 2016;7:e01326–16–9. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01326-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwong WK, Mancenido AL, Moran NA. Immune system stimulation by the native gut microbiota of honey bees. R Soc Open Sci. 2017;4:170003. doi: 10.1098/rsos.170003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Janashia I, Alaux C. Specific Immune Stimulation by Endogenous Bacteria in Honey Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) J. Econ. Entomol. 2016;109:1474–1477. doi: 10.1093/jee/tow065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alaux C, Ducloz F, Crauser D, Le Conte Y. Diet effects on honeybee immunocompetence. Biology Letters. 2010;6:562–565. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Otto CRV, Roth CL, Carlson BL, Smart MD. Land-use change reduces habitat suitability for supporting managed honey bee colonies in the Northern Great Plains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:10430–10435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603481113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dolezal AG, Carrillo-Tripp J, Miller WA, Bonning BC, Toth AL. Intensively Cultivated Landscape and Varroa Mite Infestation Are Associated with Reduced Honey Bee Nutritional State. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0153531–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smart MD, Pettis JS, Euliss N, Spivak MS. Land use in the Northern Great Plains region of the U.S. influences the survival and productivity of honey bee colonies. ‘Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment’. 2016;230:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2016.05.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smart M, Pettis J, Rice N, Browning Z, Spivak M. Linking Measures of Colony and Individual Honey Bee Health to Survival among Apiaries Exposed to Varying Agricultural Land Use. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0152685–28. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morimoto T, et al. The habitat disruption induces immune-suppression and oxidative stress in honey bees. Ecology and Evolution. 2011;1:201–217. doi: 10.1002/ece3.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di Pasquale G, et al. Variations in the Availability of Pollen Resources Affect Honey Bee Health. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0162818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brodschneider R, Crailsheim K. Nutrition and health in honey bees. Apidologie. 2010;41:278–294. doi: 10.1051/apido/2010012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crailsheim K. The protein balance of the honey bee worker. Apidologie. 1990;21:417–429. doi: 10.1051/apido:19900504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang Z. Pollen nutrition affects honey bee stress resistance. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews. 2012;5:175–189. doi: 10.1163/187498312X639568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meikle WG, et al. Internal hive temperature as a means of monitoring honey bee colony health in a migratory beekeeping operation before and during winter. Apidologie. 2017;48:666–680. doi: 10.1007/s13592-017-0512-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeGrandi-Hoffman G, Chen Y. Nutrition, immunity and viral infections in honey bees. Current Opinion in Insect Science. 2015;10:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tritschler, M. et al. Protein nutrition governs within- host race of honey bee pathogens. Sci Rep 1–11, 10.1038/s41598-017-15358-w (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Koch H, Brown MJ, Stevenson PC. The role of disease in bee foraging ecology. Current Opinion in Insect Science. 2017;21:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gong Y, Diao Q. Current knowledge of detoxification mechanisms of xenobiotic in honey bees. Ecotoxicology. 2017;26:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10646-016-1742-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zee RVD, et al. Results of international standardised beekeeper surveys of colony losses for winter 2012–2013: analysis of winter loss rates and mixed effects modelling of risk factors for winter loss. Journal of Apicultural Research. 2015;53:19–34. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.53.1.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Genersch E, et al. The German bee monitoring project: a long term study to understand periodically high winter losses of honey bee colonies. Apidologie. 2010;41:332–352. doi: 10.1051/apido/2010014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tarpy DR, Hatch S, Fletcher DJC. The influence of queen age and quality during queen replacement in honeybee colonies. Animal Behaviour. 2000;59:97–101. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tarpy DR, Keller JJ, Caren JR, Delaney DA. Experimentally induced variation in the physical reproductive potential and mating success in honey bee queens. Insect. Soc. 2011;58:569–574. doi: 10.1007/s00040-011-0180-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rangel J, Keller JJ, Tarpy DR. The effects of honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) queen reproductive potential on colony growth. Insect. Soc. 2012;60:65–73. doi: 10.1007/s00040-012-0267-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.vanEngelsdorp D, Tarpy DR, Lengerich EJ, Pettis JS. Idiopathic brood disease syndrome and queen events as precursors of colony mortality in migratory beekeeping operations in the eastern United States. Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 2013;108:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Woyke J. Correlations and Interactions Between Population, Length of Worker Life and Honey Production by Honeybees in a Temperate Region. Journal of Apicultural Research. 1984;23:148–156. doi: 10.1080/00218839.1984.11100624. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akyol, E., Yeninar, H. & Karatepe, M. Effects of queen ages on Varroa (Varroa destructor) infestation level in honey bee (Apis mellifera caucasica) colonies and colony performance. Italian Journal of … 10.4081/ijas.2007.143 (2007).

- 57.Simeunovic P, et al. Nosema ceranaeand queen age influence the reproduction and productivity of the honey bee colony. Journal of Apicultural Research. 2015;53:545–554. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.53.5.09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Salmela, H., Stark, T., Stucki, D. & Fuchs, S. Ancient duplications have led to functional divergence of vitellogenin-like genes potentially involved in inflammation and oxidative stress in honey bees. Genome biology and … 10.5061/dryad.hq669 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Al-Lawati H, Kamp G, Bienefeld K. Characteristics of the spermathecal contents of old and young honeybee queens. J Insect Physiol. 2009;55:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pettis JS, Rice N, Joselow K, vanEngelsdorp D, Chaimanee V. Colony Failure Linked to Low Sperm Viability in Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) Queens and an Exploration of Potential Causative Factors. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0147220–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tarpy DR, Mattila HR, Newton ILG. Development of the Honey Bee Gut Microbiome throughout the Queen-Rearing Process. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2015;81:3182–3191. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00307-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Anderson, K. E. et al. The queen’s gut refines with age: longevity phenotypes in a social insect model. Microbiome6, 287 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Brodschneider R, et al. Preliminary analysis of loss rates of honey bee colonies during winter 2015/16 from the COLOSS survey. Journal of Apicultural Research. 2016;55:375–378. doi: 10.1080/00218839.2016.1260240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.vanEngelsdorp D, et al. A national survey of managed honey bee 2010–11 winter colony losses in the USA: results from the Bee Informed Partnership. Journal of Apicultural Research. 2015;51:115–124. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.51.1.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Amdam GV, Norberg K, Hagen A, Omholt SW. Social exploitation of vitellogenin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100:1799–1802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0333979100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Piulachs MD, et al. The vitellogenin of the honey bee, Apis mellifera: structural analysis of the cDNA and expression studies. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2003;33:459–465. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(03)00021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Havukainen H, Halskau Ø, Skjaerven L, Smedal B, Amdam GV. Deconstructing honeybee vitellogenin: novel 40 kDa fragment assigned to its N terminus. J. Exp. Biol. 2011;214:582–592. doi: 10.1242/jeb.048314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kent CF, Issa A, Bunting AC, Zayed A. Adaptive evolution of a key gene affecting queen and worker traits in the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Mol Ecol. 2011;20:5226–5235. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Morandin C, et al. Not Only for Egg Yolk—Functional and Evolutionary Insights from Expression, Selection, and Structural Analyses of Formica Ant Vitellogenins. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2014;31:2181–2193. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Donkersley P, et al. Nutritional composition of honey bee food stores vary with floral composition. Oecologia. 2017;185:749–761. doi: 10.1007/s00442-017-3968-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moret Y, Schmid-Hempel P. Survival for immunity: the price of immune system activation for bumblebee workers. Science. 2000;290:1166–1168. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5494.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alaux, C. et al. A ‘Landscape physiology’ approach for assessing bee health highlights the benefits of floral landscape enrichment and semi-natural habitats. Sci Rep 1–10, 10.1038/srep40568 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Nelson CM, Ihle KE, Fondrk MK, Page RE, Amdam GV. The Gene vitellogenin Has Multiple Coordinating Effects on Social Organization. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e62–5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Münch D, Amdam GV, Wolschin F. Ageing in a eusocial insect: molecular and physiological characteristics of life span plasticity in the honey bee. Functional Ecology. 2008;22:407–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Seeley TD. Honey Bee Colonies are Group‐Level Adaptive Units. The American Naturalist. 1997;150:S22–S41. doi: 10.1086/286048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Seeley TD. Adaptive significance of the age polyethism schedule in honeybee colonies. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 1982;11:287–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00299306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Johnson BR. Spatial effects, sampling errors, and task specialization in the honey bee. Insect. Soc. 2010;57:239–248. doi: 10.1007/s00040-010-0077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Smith, C. R. & Tschinkel, W. R. Collecting live ant specimens (colony sampling). Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2009, pdb.prot5239–pdb.prot5239 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cox-Foster DL, et al. A metagenomic survey of microbes in honey bee colony collapse disorder. Science. 2007;318:283–287. doi: 10.1126/science.1146498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen YP, Higgins JA, Feldlaufer MF. Quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR analysis of deformed wing virus infection in the honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2005;71:436–441. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.1.436-441.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.