Abstract

Nanostructures based on buried interfaces and heterostructures are at the heart of modern semiconductor electronics as well as future devices utilizing spintronics, multiferroics, topological effects, and other novel operational principles. Knowledge of electronic structure of these systems resolved in electron momentum k delivers unprecedented insights into their physics. Here we explore 2D electron gas formed in GaN/AlGaN high-electron-mobility transistor heterostructures with an ultrathin barrier layer, key elements in current high-frequency and high-power electronics. Its electronic structure is accessed with angle-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy whose probing depth is pushed to a few nanometers using soft-X-ray synchrotron radiation. The experiment yields direct k-space images of the electronic structure fundamentals of this system—the Fermi surface, band dispersions and occupancy, and the Fourier composition of wavefunctions encoded in the k-dependent photoemission intensity. We discover significant planar anisotropy of the electron Fermi surface and effective mass connected with relaxation of the interfacial atomic positions, which translates into nonlinear (high-field) transport properties of the GaN/AlGaN heterostructures as an anisotropy of the saturation drift velocity of the 2D electrons.

Semiconductor heterostructures hosting two-dimensional electron gases are widely used today in high-electron-mobility transistors. Here, the authors probe the electronic structure in GaN/AlGaN, heterostructures, discovering planar anisotropy of the electron Fermi surface, offering new insights into transport properties.

Introduction

The concept of high-electron-mobility transistors (HEMTs) advanced by Mimura1 in the early 80s for GaAs/GaAlAs heterostructures revolutionized the field of high-frequency semiconductor electronics. It exploits an idea of polarization engineering when a large band offset between an intrinsic semiconductor and a doped barrier layer forms a quantum well (QW) at the interface that confines a mobile two-dimensional electron gas (2DEG) on the intrinsic semiconductor side. Its spatial separation from defects in the doped barrier layer and in the interface region—in contrast to conventional transistor structures where the 2DEG is formed by doping—allows the electrons to escape defect scattering and dramatically increase their mobility , limited then only by phonon scattering. This fundamental operational principle of HEMTs boosts their high-frequency performance, which is exploited in a wide spectrum of applications such as cell phones.

A characteristic property of HEMTs based on wurtzite GaN/AlGaN heterostructures is the accumulation of large sheet carrier concentrations ns ~ 1013 cm−2—about one order of magnitude higher compared with other III–V or elementary semiconductors2,3—without intentional doping of the barrier layer. This property is attributed to the formation of a deep spike-shaped QW at the heterojunction, where a large conduction band offset coexists with large piezoelectric and spontaneous polarization4,5. Although in GaN-HEMTs is limited by a relatively large electron effective mass m* ~ 0.22 in bulk GaN, nearly three times larger than in GaAs, these devices demonstrate an advantageous combination of sufficiently high operating frequency with exceptionally high current density, resulting from the large ns, saturation drift velocity, operating temperature, and breakdown voltage. These advantages make the GaN-HEMTs indispensable components of high-power amplifiers for microwave communication and radar systems. Recently, the ideas of creating mobile 2DEGs using spontaneous and strain-induced polarization at the interface have been extended to oxide systems such as the binary MgxZn1-xO/ZnO,6 LaAlO3/SrTiO37, and CaZrO3/SrTiO38 heterostructures that typically embed orders of magnitude larger ns.

The state-of-art GaN-HEMTs operate nowadays at the edge of their physical limitations, which remain far from complete understanding. Development of new strategies to improve their performance and conquer the near-THz operational range9 needs qualitatively new experimental knowledge about the physics of these devices. Particularly important is k-space information about the Fermi surface (FS), band dispersions, and wavefunctions of the embedded 2DEG. These fundamental electronic structure characteristics, only indirectly accessible in optics and magnetotransport experiments such as the Hall effect, Shubnikov-de Haas oscillations, cyclotron resonance, etc.10–12, can be directly probed using the k-resolving technique of angle-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy (ARPES). However, the small photoelectron mean free path λPE in conventional ARPES with photon energies hv around 100 eV limits its depth sensitivity to ~ 0.5 nm. Access to buried electron systems such as the HEMTs requires pushing this technique to the soft-X-ray energy range (SX-ARPES, see a recent review ref. 13) with hv around 1 keV and higher, where λPE grows with photoelectron kinetic energy as ~ Ek3/4 14,15. For GaN in particular, elastic-peak electron spectroscopy measurements16 show that an increase of Ek from 200 eV to 2 keV results in an increase of λPE from ~ 0.5 to 4 nm. An added virtue of SX-ARPES, still largely overlooked in applications to 2D systems such as QW states (QWSs), is a significantly sharper definition of the out-of-plane component Kz of the final-state momentum K. This fact results from the larger λPE translating, via the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, to a sharper definition of Kz17,18. As we will see below, in this case the ARPES signal provides the Fourier composition of the 2DEG wavefunctions. SX-ARPES on buried systems, challenged by photoelectron attenuation in the overlayers as well as a progressive reduction of photoexcitation cross-section of the valence band (VB) states with hv19, requires advanced synchrotron radiation sources delivering high photon flux (see Methods).

On the sample fabrication side, the 2DEG in GaN-HEMT heterostructures has until recently remained inaccessible to SX-ARPES because of the prohibitively large—of the order of 20–30 nm—depth of the AlGaN barrier layers. However, recent progress in molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) technology, in pursuit of yet higher operation frequencies of these devices, has allowed fabrication of heterostructures with ultrathin barrier layers of 3–4 nm20–22, which make them ideally suited to SX-ARPES. This has allowed direct k-space imaging of the fundamental electronic structure characteristics—the FS, electron dispersions, and the Fourier composition of wavefunctions—of the interfacial 2DEG in such heterostructures.

Results

Fabrication and basic electronic properties of GaN-HEMT heterostructures

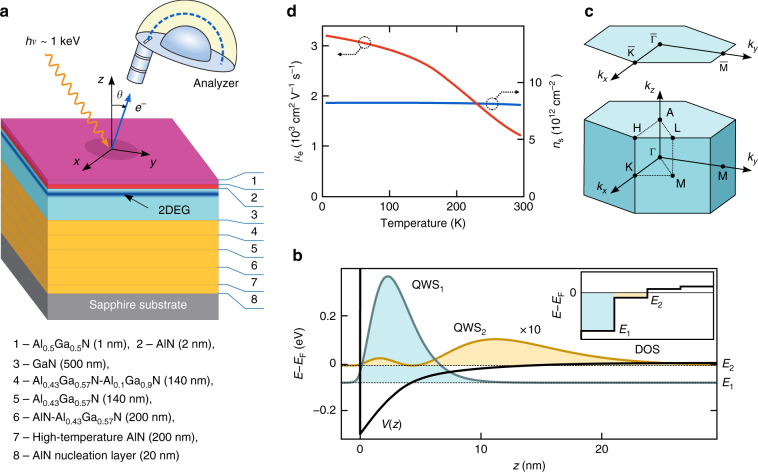

Our samples were grown on c-oriented sapphire substrate (see Methods). The 500 nm-thick Ga-polar GaN layer was grown on top of an AlGaN buffer layer required to suppress the crystal defects and promote growth of a smooth uniform film23. The GaN layer was overgrown by a barrier layer consisting of 2 nm of AlN and 1 nm of Al0.5Ga0.5N, see Fig. 1a. Hall-effect measurements on our samples, 1b, have found ns ~ 8.2 × 1012 cm−2 almost constant through the temperature range T = 5-300 K that confirms the high quality of the fabricated structures.

Fig. 1.

SX-ARPES experiment on the GaN-HEMT heterostructure. a Scheme of the epitaxial GaN-HEMT samples investigated by SX-ARPES. The photoelectron analyser detects the distribution of the photoelectron kinetic energy Ek and emission angle , which yield the binding energy EB and momentum k back in the sample (corrected for the photon momentum p = hv/c) to produce the sought-for electron dispersions E(k). b T-dependence of ns and obtained from Hall measurements. c Sketch of the electronic structure based on self-consistent solution of the 1D Poisson-Schrodinger equation. The quasi-triangular 1D potential V(z) confines two QWSs having different spatial localization of their electron density ni(z) (exaggerated by × 10 for the QWS2) centered at ~ 3 and ~ 12 nm for QWS1 and QWS2, respectively. The total three-dimensional DOS (insert) show steps characteristic of the 2D states. d Bulk BZ of GaN and 2D one of the GaN/AlGaN heterostructure

A simplified electronic structure model of our GaN-HEMTs is shown in Fig. 1b. It was evaluated within the conventional envelope function approach (neglecting atomic corrugation) by self-consistent solutions of the one-dimensional (1D) Poisson–Schrödinger equations with the Dirichlet boundary conditions adjusted to reproduce the experimental ns (for details see Supplementary Note 1). The effective 1D interfacial potential V(z) as a function of out-of-plane coordinate z confines two QWSs with different spatial localization. The QWS1 embeds larger partial ns and is localized closer to the interface compared to the QWS2, which is shifted into the V(z) saturation region.

FS: anisotropy and carrier concentration

A scheme of our SX-ARPES experiment is presented in Fig. 1a. The data were acquired in the hv region between 800 and 1300 eV where the interplay of photoelectron transmission through the barrier overlayer increasing with hv and photoexcitation cross-section decreasing with hv maximizes the QWS signal. In view of the even QWS wavefunction symmetry, we used p-polarization of the incident X-rays, which minimizes the geometry- and polarization-related matrix element effects, which distort the direct relation between ARPES intensities and Fourier composition of the QWS wavefunctions (see below).

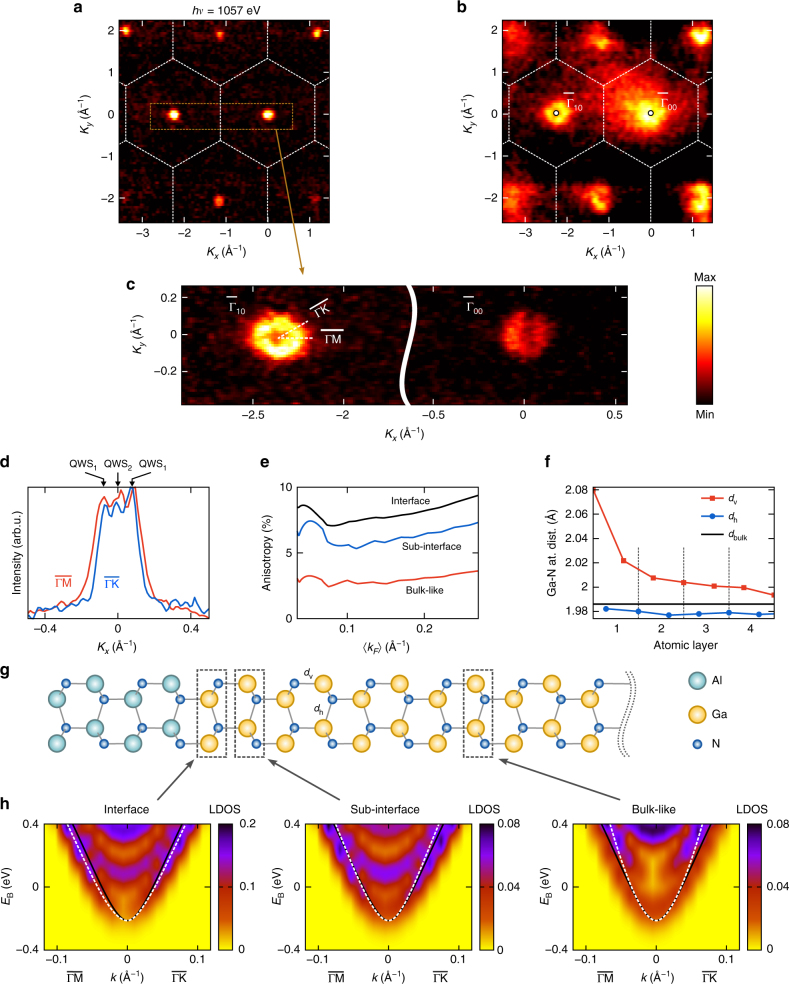

The experimental FS map measured as a function of in-plane momentum Kxy = (Kx,Ky) at hv = 1057 eV (maximizing the QWS signal, see below) is presented in Fig. 2a. The FS formed by the QWSs in the HEMT channel appears as tiny circles whose k// are located around the -points of the heterostructure’s 2D Brillouin zone (BZ) shown in Fig. 1c. The location of the FS pockets coincides with the VB maxima (VBM), as seen in an iso-EB map of the VB shown in Fig. 2b. In the direct band gap GaN, this location in k// is consistent with the conduction band minimum (CBM)-derived character of the QWSs.

Fig. 2.

FS formed by the buried 2DEG. a Experimental FS formed by the 2DEG in comparison with b iso-EB surface of the VB near the VBM. The FS appears as narrow electron pockets centered at the around the -points, consistent with the CBM-derived character of the 2DEG. Both VB and FS maps reflect the C6v symmetry of the GaN crystal lattice. c FS along the line acquired with high energy and angle resolution. d MDCs of the Fermi intensity around the -point (derived from the high-statistics data in Fig. 4) identifying the tiny QWS2 and anisotropy of the QWS1 between the and azimuths with AF ~ 12%. e Calculated AF of QWS1 between and as a function of band filling characterized by < kF > , for bulk GaN and for various heterostructure layers. f Relaxation of the Ga-N bond length as a function of depth and g u.c. used in the slab calculations. h k//-resolved LDOS for various heterostructure layers near the CBM with EF adjusted to the experimental < kF > and superimposed with the corresponding bulk E(k) along ГM and ГK (black lines). The QWS1 dispersion (white dashed in the bottom of the LDOS continuum) in the top GaN layers shows an asymmetry related to the interfacial atomic relaxation

A high-resolution cut of the FS in Fig. 2c displays an external contour with a diameter of ~ 0.2 Å−1 manifesting the QWS1 and finite spectral weight in the middle, suggesting the presence of QWS2. The latter is confirmed by the momentum-distribution curves (MDCs) of the Fermi intensity around the -points (Fig. 2d) where a weak structure in the middle signals the QWS2. Our observation of QWS2 is consistent with its recent detection via magnetotransport spectroscopy24. The presence of this state centered further away from the interface compared with the QWS1 indicates that V(z) in the GaN-HEMTs has a long-range saturated shape (see the model in Fig. 1b). The external Fermi intensity peaks in the EF-MDCs directly identify the Fermi momenta kF of the QWS1.

Such a comprehensive k-space view of the buried QWSs, achieved with SX-ARPES, delivers two important observations. First, the experimental EF-MDCs reveal significant anisotropy of the FS characterized by a difference of the kF values of 0.095 ± 0.006 Å−1 along the azimuth and 0.085 ± 0.004 Å−1 along .These values were determined from the maximal gradient of the Fermi intensity25, which delivers accurate kF-values even when the bandwidth is comparable with the experimental resolution. The indicated statistical errors are the standard deviations of the kF values over the measurement series and scaled with the Student’s t-distribution coefficients for a confidence interval of 76%. The corresponding kF anisotropy factor , where , measures in our case ~ 11%. Such a considerable FS anisotropy has been completely overlooked in previous macroscopic experimental studies without k-resolution.

Why does the 2DEG show such a pronounced planar anisotropy? Our simulations of electronic structure of the GaN-HEMTs (see Methods) used the standard density-functional theory (DFT), which is known to well describe excitation energies in GaN apart from the electron exchange-correlation discontinuity across the band gap approximated by the so-called scissors operator26. As the QWSs inherit their wavefunctions from the CBM of the bulk GaN (see below), we have started our analysis from band structure. The corresponding AF in Fig. 2e is however negligible through the whole range of < kF > defining the band filling. Next, we approached the electronic structure of our heterostructure system using GaN/AlN slab calculations with the unit cell (u.c.) shown in Fig. 2g. The atomic positions were relaxed under the constraint of the bulk GaN lateral lattice constants and symmetry. The resulting c-oriented Ga-N bond length dv in Fig. 2f shows a significant increase toward the interface relative to the bulk value. The corresponding atomic displacement contributes to the piezoelectric polarization at the GaN/AlN interface. The layer-resolved electronic structure of this system was characterized by the k//-resolved layer density of states (LDOS) defined as, , where r = (x,y,z), the summation includes all n-th electron states with wavefunctions available for given k// and E, and the integration runs over the lateral unit cell Ω. Figure 2h shows the LDOS calculated near the CBM (the VB results are given in Supplementary Note 2) for the interface, sub-interface, and deep bulk-like GaN layers, where the bottom of the LDOS continuum corresponds to the QWS1. The corresponding AF plots in 2e now show significant anisotropy, increasing toward the interface. At the experimental < kF > the interface layer AF is ~ 7%, which falls almost within the error bars of the experimental value. Finally, we performed the same LDOS calculations with the atomic coordinates in the slab fixed at the bulk values (without relaxation). AF immediately returned to the negligible bulk values. This analysis suggests thus that the discovered 2DEG anisotropy in GaN-HEMTs is a purely interface effect caused by relaxation of atomic position near the GaN/AlN interface.

We note however that the predicted atomic relaxation is restricted to a few atomic layers next to the interface, and it is not clear why it should significantly affect the 2DEG, whose maximal density is located ~ 3 nm away from this region (Fig. 1b). In fact, even the state-of-art growth methods leave significant intermixing of Ga and Al atoms at the GaN/AlN interface21, resulting in a gradual variation of the lattice parameters over 1–3 nm from the interface. In the spirit of the entanglement between atomic relaxation and LDOS anisotropy, revealed by our computational analysis, this lattice distortion may cause significant electronic structure anisotropy extending into the 2DEG localization region.

Another important characteristic of the buried 2DEG is the experimental FS area which, by the Luttinger theorem27, is directly related to the ns sheet carrier concentration. In our case, the area of the external QWS1 contour translates into partial = (12.8 ± 1.4) × 1012 cm−2, and that of the internal QWS2 contour into = (0.5 ± 0.4) × 1012 cm−2. We note that the emergence of two QWSs goes together with large ns formed in the anomalously deep QW of the GaN-HEMTs. In our case, the QWS2 contributes only ~ 4% of the total ns dominated by the QWS1. A significant difference of this ratio to that of 17% found in a cyclotron resonance study28 is explained by extremely high sensitivity of the QWS2 population to the interfacial QW depth in different samples. The total ns in our case amounts to (13.3 ± 1.8) × 1012 cm−2, which is in fair agreement with ns = 8.2 × 1012 cm−2 obtained by our Hall characterization, see Fig. 1d, in particular taking into account a small systematic overestimate of kF introduced by the gradient method25.

Momentum dependence of ARPES intensity: wavefunction character

Within the one-step theory of photoemission—see, e.g., ref. 29—the ARPES intensity is found as , where is the final and the initial states coupled through the vector potential A of the incident electromagnetic field and momentum operator p. Neglecting the experimental geometry and polarization effects, this expression simplifies to the scalar product . For sufficiently high photon energies, approximates a plane wave periodic in the in-plane xy direction and damped in the out-of-plane direction z, and the ARPES intensity appears30,31 as . We will now apply this formalism to the QWS wavefunctions .

We will first analyze IPE as a function of photoelectron Kxy in-plane momentum. If we represent by Fourier expansion over 2D reciprocal vectors g as , the plane-wave orthogonality will select from the sum only the component whose in-plane momentum kxy+g matches Kxy (corrected for the photon momentum p = hv/c), i.e., . Therefore, the (Kx,Ky)-dependent ARPES maps in Fig. 2a–c visualize essentially the 2D Fourier expansion of 30,31.

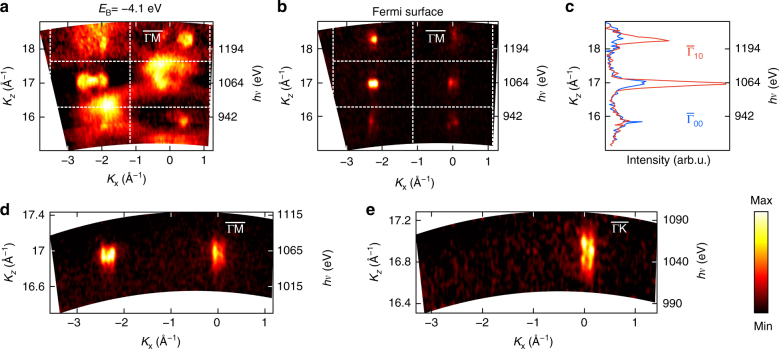

We will now analyze IPE as a function of photoelectron Kz out-of-plane momentum varied in the experiment through hv. The corresponding iso-EB map in (Kx,Kz) coordinates near the VBM is displayed in Fig. 3a. Its Kz-dispersive contours demonstrate the three-dimensional (3D) character of the VB states inherited from bulk GaN. The FS in Fig. 3b formed by the QWSs demonstrates a different behavior however: the ARPES signal sharply increases whenever Kz approaches values of integer Gz—corresponding to the Γ-points of the bulk BZ, but without any sign of Kz dispersion. The latter is emphasized by the zooms in Fig. 3d,e, where the QWSs form segments straight in the Kz direction. This pattern is characteristic of the 2D nature of the QWSs. The corresponding Fermi intensity is represented by EF-MDCs in Fig. 3c that show periodic oscillations peaked where Kz matches the Γ-points.

Fig. 3.

ARPES response of the 2DEG as a function of Kz momentum. ARPES intensity along the indicated azimuths is plotted as a function of Kz rendered from hv (the indicated hv values correspond to the -point) a Iso-EB map near the VBM, showing 3D contours of the VB states. b FS formed by the QWSs. c EF-MDCs at the - and -points, showing periodically oscillating response of the QWSs. Its peaks located in the Γ-points evidence that the QWSs inherit their wavefunction from the CBM of parent bulk GaN. Zoom-in of the FS at the - and -points along the d and e measured at around 1070 eV. The absence of its Kz dispersion confirms the 2D character of the QWSs

Why do the QWSs display such an ARPES response, periodically oscillating as a function of hv? The dependence of on z for given Kxy is represented as , where the envelope function E(z) confines the oscillating Bloch wave whose kz momentum is adapted to the 3D crystal potential32. In our case, the first term is an Airy-like function embedded in the approximately triangular V(z) and the second one derives from bulk states of the GaN host. Inheriting ideas of early ARPES studies on surface states32,33, it can be shown34 that if we expand over out-of-plane reciprocal vectors Gz of the 3D host lattice as , then the Kz dependence of ARPES intensity for given Kxy appears as a sequence of peaks centered at Kz = kz + Gz. Physically, the ARPES intensity blows up whenever the photoelectron Kz hits a kz + Gz harmonic of to maximize the and scalar product. Amplitudes of the peaks image Fourier composition of the oscillating term of (modulated by hv-dependent photoelectron transmission through the AlGaN/AlN layer) and the peak shapes are related to the Fourier transform of the E(z) term weighted by 34.

Importantly, the experimental Kz dependence of the QWS signal in Fig. 3b exhibits peaks exactly at kz + Gz, corresponding to the Γ-point of bulk GaN. In combination with the (Kx,Ky) image in Fig. 2, where the QWS signal corresponds to the same Γ-point, this fact confirms that the ’s are derived from the CBM states of bulk GaN. In a methodological perspective, such identification of the character can be essential, e.g., for heterostructures of layered transition metal dichalcogenides, where the CB can include two or more valleys almost degenerate in energy but separated in k. The knowledge of the QWS character will then allow the predictive manipulation of the valley degree of freedom for potential valleytronics devices35.

We note that the common models of QWSs based on the 1D potential V(z), such as that in Fig. 1b, imply that their in-plane behavior is described by one single plane wave (i.e., one non-zero component) and out-of-plane behavior is identical to the smooth E(z) function. However, the experimental FS maps in Fig. 2a,c reveal numerous non-zero spread through k-space and the oscillations numerous kz + Gz harmonics. Accurate QWS models should therefore incorporate atomic corrugation of the interfacial potential in the in-plane and out-of-plane directions to form as a confined Bloch wave.

The experimental distribution of high-energy ARPES intensity over sufficiently large volume of the (Kx,Ky,Kz) space will in principle allow, notwithstanding the phase problem, a full reconstruction of in all three spatial coordinates, similar to the reconstruction of molecular orbitals (see refs. 30,31, and references therein). This reconstruction will naturally incorporate full including the envelope and Bloch-wave terms that goes beyond the common 1D models such as in Fig. 1b, describing the QWSs as free 2D electrons with empirical m* confined in the z direction. More accurate models of the GaN-HEMTs should replace free electrons by Bloch ones, naturally incorporating atomic corrugation.

Band dispersions: effective mass

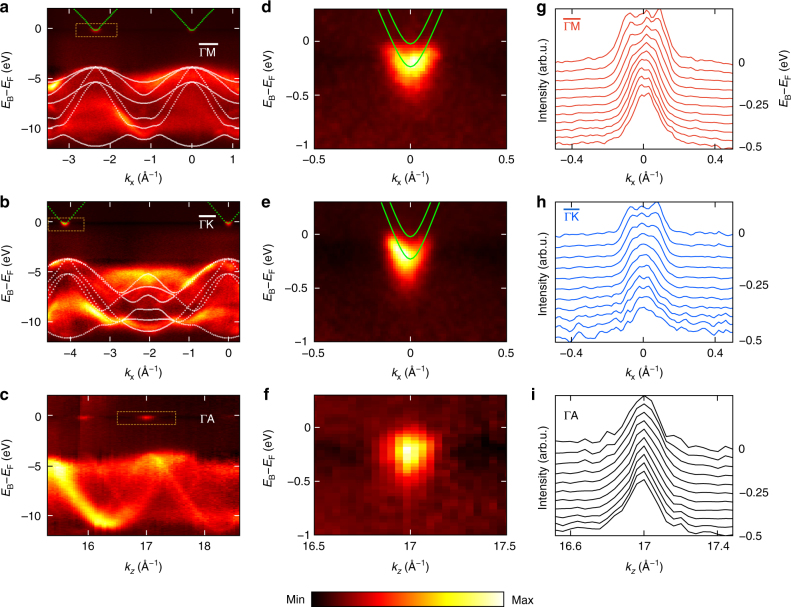

Experimental band dispersions in GaN-HEMTs shown in Fig. 4 were measured along (a) and (b) at hv = 1066 eV bringing Kz to the Γ-point of the bulk BZ. Non-dispersive ARPES intensity coming from the AlN and AlGaN layers is suppressed in these plots by subtracting the angle-integrated spectral component. The CBM-derived QWSs appear as tiny electron pockets above the VB dispersions of GaN. Their energy separation from the VBM is consistent with the GaN fundamental band gap of ~ 3.3 eV. Whereas the VB dispersions are broadened in EB primarily because of band bending in the QW region, the QWS dispersions stay sharp. This confirms their 2D nature insensitive to band bending as well as their localization in the deep defect-free region in GaN, spatially separated from the defect-rich GaN/AlN interface region, the fundamental operational principle of the HEMTs delivering high . Fig. 4c,f,i show the experimental dispersions as a function of kz. Whereas clear dispersion of the VB states manifests their 3D character, the QWS are flat in Kz.

Fig. 4.

Band dispersions of the buried 2DEG. a–c Experimental band structure measured at hv = 1066 eV for the a ΓK and b ΓM directions of the bulk BZ (superimposed with calculated E(k) of bulk GaN, white dashed lines) and under variation of hv for c ΓA, cf. Fig. 3. The CBM-derived QWSs appear above the VB continuum. d–f Zoom-in image of the QWSs around the -point (green lines schematize their dispersions fitting the experimental kF). g–i (Normalized) MDCs around the -point for a series of EB through the QWS bandwidth. The difference between the and dispersions manifests planar anisotropy of the 2DEG, and the absence of kz dispersion confirms its 2D character

A zoom-in of the QWS dispersions along the and azimuths is shown in Fig. 4d,e with the corresponding MDC in Fig. 4g,h. Whereas the outer contour of these dispersions corresponds to the QWS1, the significant spectral weight in the middle is due to the QWS2. Following the kF anisotropy discussed above, a parabolic fit of the QWS1 dispersions yields m* values of (0.16 ± 0.03)m0 along the azimuths and (0.13 ± 0.02)m0 along (m0 is the free-electron mass), which thus differ from each other by ~ 22%.

Our SX-ARPES experiment presents thus a direct evidence of the planar FS and m* anisotropy in GaN-HEMTs. This effect was overlooked in previous studies, because the optics methods are k-integrating and quantum oscillation techniques lose their k-resolution in the 2D case. Magnetotransport experiments give only an indirect information on the 2DEG’s m*10–12, which is conventionally36,37 assumed to be isotropic. We conjecture that further progress of SX-ARPES on energy resolution will push data analysis from merely band structure to one-electron spectral function A(ω,k), which will inform, e.g., the interaction of electrons with other quasiparticles such as the phonon-plasmon-coupled modes.38

Implications for the transport properties

How will the observed lateral anisotropy of the 2DEG electronic structure affect the transport properties? Naively, one might think that it would directly translate into an anisotropy of the electrical conductivity. However, fundamental linear response considerations attest that any physical properties such as conductivity described by a second-order tensor with C6v symmetry must be scalar, i.e., in the linear (low-field) regime, conductivity in the hexagonal lattice of GaN must be isotropic (Supplementary Note 3). On the other hand, this restriction is lifted for the nonlinear (high-field) regime where conductivity can become anisotropic. A canonical example of such a crossover is n-doped Ge.39,40 Although its FS is anisotropic, cubic symmetry of the Ge lattice results in isotropic low-field conductivity. However, with an increase of the electric field, conductivity along the , , and crystallographic directions develops differently. The GaN-HEMTs can be easily driven into the nonlinear regime where electronic current saturates due to electron scattering on longitudinal optical (LO) phonons41,42. To reach the LO phonon energy, lighter electrons should gain a larger drift velocity Vsat. Therefore, larger Vsat and thus saturation current Isat should be expected in the directions of smaller m*.

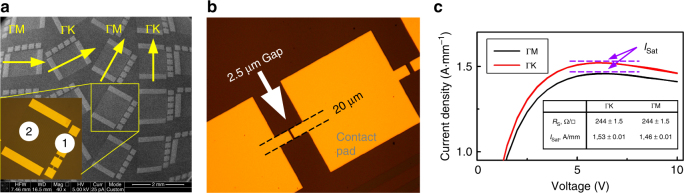

We have examined low- and high-field conductivity in our GaN-HEMT heterostructures using samples essentially identical to the ARPES ones, but with the Al0.45Ga0.55N layer thickness increased to 15 nm, to prevent a 2DEG degradation during longer sample handling in air. Hall measurements showed ns = 2 × 1013 cm−2, μe = 1150 cm2 V−1 s, and sheet resistance Rs = 240 Ω sq−1 for these samples. The fabricated test modules were oriented at four different angles (0°, 30°, 60°, 90°) with respect to the substrate to promote current flow along the and azimuths (Fig. 5a,b). Results of the transport measurements presented in Fig. 5c show, as expected, isotropic low-field Rs. However, the Isat characteristic of the high-field regime is clearly anisotropic: 1.53 ± 0.01 A × mm−1 along and 1.46 ± 0.01 A × mm-1 along (Fig. 5c). As a consistency check, the modules rotated by 60° with respect to each other showed the same Isat values, in accordance with hexagonal symmetry of the GaN electronic structure. These results on the previously overlooked Isat anisotropy demonstrate that m* along is smaller compared to , as predicted by our ARPES results.

Fig. 5.

Electron transport measurements. a Test modules, oriented in four directions (scanning electron microscope images, slightly distorted due to large view area): TLM modules for the contact resistance measurements (marked 1 in the inset) and ‘resistor’ modules for Rs determination (marked 2). The yellow arrows indicate the TLM azimuthal orientation. b Region of the TLM modules with the channel length 2.5 μm used for the I–V measurements (optical microscope image). c I–V characteristics for the and azimuths. The inset table summarizes the mean Rs and Isat values for different azimuths. Although Rs is essentially isotropic, higher Isat for the azimuth in comparison with indicates smaller m* of electrons moving along

Discussion

Our direct k-space imaging of the fundamental electronic structure characteristics—FS, band dispersions and occupancy, and Fourier composition of wavefunctions—of the 2DEG formed in high-frequency GaN-HEMTs with ultrathin barrier layer makes a quantitative step compared to conventional optics and magnetotransport experiments. We discover, in particular, significant planar anisotropy of the 2DEG band dispersions caused by piezoelectrically active relaxation of atomic position near the GaN/AlN interface. This effect is found to manifest itself in nonlinear electron transport properties as anisotropy of the saturation drift velocity and current. Our findings suggest a positive use of the crystallographic orientation to improve these high-power characteristics of GaN-HEMTs. Furthermore, our k-space image of the Fourier composition of the 2DEG wavefunctions calls for extension of the conventional 1D models of semiconductor interfaces to 3D ones based on the Bloch-wave description naturally incorporating atomic corrugation. The fundamental knowledge about GaN-HEMTs achieved in our work as well as new device simulation methods can clarify the physical limits of these heterostructures, and finally push their reliable operation into the near-THz range. Methodologically, we have demonstrated the power of the synchrotron radiation based technique of SX-ARPES with its enhanced probing depth and sharp definition of the full 3D k for the discovery of previously obscured properties of semiconductor heterostructures. Our results complement previous applications of SX-ARPES to buried oxide interfaces7 and magnetic impurities in semiconductors43 and topological insulators44, which used elemental and chemical-state specificity of this technique achieved with resonant photoemission. In a broader perspective, our methodology arms the heterostructure growth technology with means to directly control the fundamental k-space parameters of the electronic structure, thereby delivering optimal transport and optical properties of the fabricated devices. Complementary to imaging of non-equilibrium electron motion in spatial coordinates,45 we can envisage an extension of our experimental methodology to pump–probe experiments using X-ray free-electron laser sources, which will image the electron system evolution in k-space during transient processes in electronic devices.

Methods

Sample fabrication

The GaN-HEMT heterostructures embedding a 2DEG were grown on c-oriented sapphire substrate in a SemiTeq STE3N MBE-system equipped with an ammonia (NH3) nitrogen source. The buffer layer growth adopted the procedure described in ref. 23. Before deposition, the substrate was annealed during 1 h and then nitrided for 40 min with 30 sccm NH3 at 850 °C. The following growth was carried out with 200 sccm NH3. Deposition started with 20 nm AlN layer, grown at 1050 °C. The following 200 nm AlN layer was grown at 1120 °C with Ga used as a surfactant. Then a gradient junction to Al0.43Ga0.57N with a thickness of ~ 250 nm was achieved by a gradual decrease of the substrate temperature down to T = 830 °C, followed by 140 nm of growth at constant T. Next, a second gradient junction to Al0.1Ga0.9N with a thickness of ~ 140 nm was formed by reducing T of the Al effusion cell. Then a 500 nm GaN layer was grown. The growth was finished by deposition of a barrier layer consisting of 2 nm AlN and 1 nm Al0.5Ga0.5N for the ARPES experiments, and 1 nm AlN and 15 nm Al0.45Ga0.55N for measurements of transport properties. Hall effect characterization was carried out in magnetic fields up to 40 kG. The magnetic-field dependences were measured in both the standard Hall and van der Pauw geometries. All transport measurements were carried out at the Resource Center of Electrophysical Methods (Complex of NBICS-Technologies of Kurchatov Institute).

SX-ARPES experiments

Raw SX-ARPES data were generated at the Swiss Light Source synchrotron radiation facility (Paul Scherrer Institute, Switzerland). The experiments have been carried out at the SX-ARPES endstation46 of the ADRESS beamline47, delivering high photon fluxes up to 1013 photons × s−1 × (0.01% BW)−1. With the actual experimental geometry, p-polarized incident X-rays selected electron states symmetric relative to the and azimuths. The projection Kx of the photoelectron momentum was directly measured through the emission angle along the analyser slit, Ky is varied through tilt rotation of the sample, and kz through hv. The experiments were carried out at 12 K to quench the thermal effects reducing the coherent k-resolved spectral component at high photoelectron energies48. The combined (beamline and analyzer) energy resolution was ~ 150 meV and the angular resolution of the PHOIBOS-150 analyzer was 0.07°. The X-ray spot size in projection on the sample was 30 × 75 μm2, which allowed us to control spatial homogeneity of our samples. Charging effects were not detected due to the small thickness of the AlGaN barrier layer.

Electronic structure calculations

First-principles calculations for bulk GaN have been carried out in the DFT framework as implemented in the pseudopotential Quantum Espresso code49 using ultrasoft pseudopotentials. The electron exchange-correlation term was treated within the Generalized Gradient Approximation using the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof functional. Self-consistent calculations for bulk GaN were performed with the plane-wave cutoff energy 60 Ry and k-space sampling over a grid of 10 × 10 × 5 points in the BZ and corrected with the scissors operator to reproduce the experimental band gap. Calculations for the GaN-HEMT heterostructure used a 1 × 1 slab geometry with the supercell including 18 u.c. of GaN in the middle between 3 u.c of AlN at each end, Fig. 2g. Atomic coordinates in the supercell were relaxed, but imposing the lateral u.c. of bulk GaN until the Hellmann–Feynman forces on each atom were < 30 meV Å−1. The plane-wave cutoff energy was 25 Ry with a k-grid of 10 × 10 × 1 points. The Gaussian window for LDOS calculations was set to 0.05 eV.

Transport measurements

Raw transport data were generated at the Kurchatov Institute. To measure linear and nonlinear transport properties of the GaN-HEMT heterostructures, two types of test modules with low-resistance regrown ohmic contacts50,51 were formed. Details on processing can be found in ref. 51. The first type modules were conventional transmission line measurement (TLM) modules with a channel width of 20 μm and channel lengths of 2.5, 10, 20, and 40 μm (marked 1 in Fig. 5a). These modules were used to determine contact resistance, which was found to be 0.15 Ω mm. Also I–V curves were measured at the smallest gaps (2.5 μm length channels, see Fig. 5b) of 24 such TLM modules (6 modules per each of four directions) in DC mode. The voltage sweep time (1 ms per point with a voltage step of 0.5 V) was chosen to be small enough to suppress sample heating effects as judged by the absence of hysteresis in the forward and backward voltage scans as well as repeatability of the I–V curves with a sweep time reduction. The second type “resistor” modules (marked 2 in Fig. 5a) were arrays of 1 mm long and 20 μm wide stripes (25 stripes per module separated by 20 μm mesa isolation) with contact pads on each side. These modules had negligible contact resistance and were used for precise measurement of the 2DEG low-field conductivity in different directions.

Data availability

Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request. The SX-ARPES data were processed using the custom package MATools available at https://www.psi.ch/sls/adress/manuals.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank M.B. Tsetlin, V.G. Nazin, E.E. Krasovskii, and G. Aeppli for fruitful discussions. M.-A.H. was supported by the Swiss Excellence Scholarship grant ESKAS-no. 2015.0257. N.K.C. was partly supported by the Grant RFBR 16-07-01188.

Author contributions

L.L.L. and V.N.S. conceived the SX-ARPES research at the Swiss Light Source. L.L.L., M.-A.H., and V.N.S. performed the SX-ARPES experiment supported by X.W., B.T., and T.S. L.L.L. and V.N.S. processed and interpreted the data. V.N.S. set theoretical description of the ARPES response. M.-A.H. performed the DFT calculations. M.L.Z., I.O.M., E.S.G., and V.G.V. conceived the GaN-HEMT project at the Kurchatov Institute. I.O.M. and I.S.E. grew the samples supported by M.L.Z. N.K.C. performed Hall characterization. E.S.G. implemented the 2DEG numerical model. I.O.M., I.A.C., and M.L.Z. fabricated the TLM modules and performed transport measurements. V.N.S. wrote the manuscript with contributions of L.L.L., V.G.V., E.S.G., and I.O.M. All authors discussed the results, interpretations, and scientific concepts.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: L. L. Lev, I. O. Maiboroda, V. N. Strocov.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-04354-x.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mimura T. The early history of the high electron mobility transistor (HEMT) IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn. 2002;50:780–782. doi: 10.1109/22.989961. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurusinghe MN, Davidsson SK, Andersson TG. Two-dimensional electron mobility limitation mechanisms in AlxGa1−xN∕GaN heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B. 2005;72:045316. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.72.045316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medjdoub, F. & Iniewski, K. (eds). Gallium Nitride (GaN): Physics, Devices, and Technology (CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, 2016).

- 4.Yu ET, et al. Measurement of piezoelectrically induced charge in GaN/AlGaN heterostructure field-effect transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1997;71:2794–2796. doi: 10.1063/1.120138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaska R, et al. The influence of the deformation on the two-dimensional electron gas density in GaN–AlGaN heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1998;72:64–66. doi: 10.1063/1.120645. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsukazaki A, Ohtomo A, Kita T. Quantum Hall effect in polar oxide heterostructures. Science. 2007;315:1388–1391. doi: 10.1126/science.1137430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cancellieri C, et al. Polaronic metal state at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interface. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10386. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, et al. Creation of high mobility two-dimensional electron gases via strain induced polarization at an otherwise nonpolar complex oxide interface. Nano Lett. 2015;15:1849–1854. doi: 10.1021/nl504622w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagatsuma T, Ducournau G, Renaud CC. Advances in terahertz communications accelerated by photonics. Nat. Photonics. 2016;10:371–379. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2016.65. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shockley W. Cyclotron resonances, magnetoresistance, and Brillouin zones in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. 1953;90:491. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.90.491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krieger JB, Meeks T, Esposito E. Conductivity in anisotropic semiconductors: application to longitudinal resistivity and Hall effect in saturation-stressed degenerately doped n-type germanium. Phys. Rev. B. 1972;5:1499–1504. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.5.1499. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brandt NB, Chudinov SM. Shubnikov-de Haas effect and its application to investigation of the energy spectrum of metals, semimetals, and semiconductors. Sov. Phys. Usp. 1982;25:518–529. doi: 10.1070/PU1982v025n07ABEH004575. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strocov VN, et al. Soft-X-ray ARPES at the Swiss Light Source: From 3D materials to buried interfaces and impurities. Synchrotron Radiat. News. 2014;27:31–40. doi: 10.1080/08940886.2014.889550. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powell CJ, Jablonski A, Tilinin IS, Tanuma S, Penn DR. Surface sensitivity of Auger-electron spectroscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 1999;98/99:1–15. doi: 10.1016/S0368-2048(98)00271-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gray AX, et al. Bulk electronic structure of the dilute magnetic semiconductor Ga1−xMnxAs through hard X-ray angle-resolved photoemission. Nat. Mater. 2012;11:957–962. doi: 10.1038/nmat3450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krawczyk M, Zommer L, Jablonski A, Grzegory I, Bockowski M. Energy dependence of electron inelastic mean free paths in bulk GaN crystals. Surf. Sci. 2004;566–568:1234–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.susc.2004.06.098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strocov VN. Intrinsic accuracy in 3-dimensional photoemission band mapping. J. Electron Spectros. Relat. Phenom. 2003;130:65–78. doi: 10.1016/S0368-2048(03)00054-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strocov VN, et al. Three-dimensional electron realm in VSe2 by soft-X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy: origin of charge-density waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;109:086401. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.086401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeh JJ, Lindau I. Atomic subshell photoionization cross sections and asymmetry parameters: 1≤ Z≤ 103. At. data Nucl. data Tables. 1985;32:1–155. doi: 10.1016/0092-640X(85)90016-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao Y, et al. MBE growth of high conductivity single and multiple AlN/GaN heterojunctions. J. Cryst. Growth. 2011;323:529–533. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2010.12.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaun SW, et al. Pure AlN layers in metal-polar AlGaN/AlN/GaN and AlN/GaN heterostructures grown by low-temperature ammonia-based molecular beam epitaxy. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2015;30:055010. doi: 10.1088/0268-1242/30/5/055010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo L, et al. Hot electron induced non-saturation current behavior at high electric field in InAlN/GaN heterostructures with ultrathin barrier. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:37415. doi: 10.1038/srep37415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayboroda I, et al. Growth of AlGaN under the conditions of significant gallium evaporation: phase separation and enhanced lateral growth. J. Appl. Phys. 2017;122:105305. doi: 10.1063/1.5002070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu F, et al. Magneto-transport spectroscopy of the first and second two-dimensional subbands in Al0.25Ga0.75N/GaN quantum point contacts. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:42974. doi: 10.1038/srep42974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Straub Th, et al. Many-body definition of a Fermi surface: application to angle-resolved photoemission. Phys. Rev. B. 1997;55:13473–13478. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.55.13473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Svane A, et al. Quasiparticle self-consistent GW theory of III-V nitride semiconductors: bands, gap bowing, and effective masses. Phys. Rev. B. 2010;82:115102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.82.115102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luttinger JM. Fermi surface and some simple equilibrium properties of a system of interacting fermions. Phys. Rev. 1960;119:1153–1163. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.119.1153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mishra MK, et al. Comprehensive magnetotransport characterization of two dimensional electron gas in AlGaN/GaN high electron mobility transistor structures leading to the assessment of interface roughness. AIP Adv. 2014;4:097124. doi: 10.1063/1.4896192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feibelman PJ, Eastman DE. Photoemission spectroscopy – correspondence between quantum theory and experimental phenomenology. Phys. Rev. B. 1974;10:4932–4947. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.10.4932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puschnig P, et al. Reconstruction of molecular orbital densities from photoemission data. Science. 2009;326:702–706. doi: 10.1126/science.1176105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kliuiev P, Latychevskaia T, Osterwalder J, Hengsberger M, Castiglioni L. Application of iterative phase-retrieval algorithms to ARPES orbital tomography. New. J. Phys. 2016;18:093041. doi: 10.1088/1367-2630/18/9/093041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ortega JE, Himpsel FJ, Mankey GJ, Willis RF. Quantum-well states and magnetic coupling between ferromagnets through a noble-metal layer. Phys. Rev. B. 1993;47:1540–1552. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.47.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Louie SG, et al. Periodic oscillations of the frequency-dependent photoelectric cross sections of surface states: theory and experiment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980;44:549–553. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.44.549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strocov, V. N. Photoemission response of 2D states. Preprint at http://arXiv.org/abs/1801.07505 (2018).

- 35.Schaibley JR, et al. Valleytronics in 2D materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016;1:16055. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.55. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knap W, et al. Effective g* factor of two-dimensional electrons in GaN/AlGaN heterojunctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1999;75:3156–3158. doi: 10.1063/1.125262. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Syed S, et al. Nonparabolicity of the conduction band of wurtzite GaN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003;83:4553–4555. doi: 10.1063/1.1630369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Talwar DN. Direct evidence of LO phonon-plasmon coupled modes in n-GaN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010;97:051902. doi: 10.1063/1.3473826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schweitzer D, Seeger K. The anisotropy of conductivity of n-type germanium in strong D.C. fields. Z. für Phys. 1965;183:207–216. doi: 10.1007/BF01380796. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nathan MI. Anisotropy of the conductivity of n-type germanium at high electric fields. Phys. Rev. 1963;130:2201–2204. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.130.2201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fang T, et al. Effect of optical phonon scattering on the performance of GaN transistors. IEEE Electron Dev. Lett. 2012;33:709–711. doi: 10.1109/LED.2012.2187169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gonschorek M, et al. Self heating in AlInN/AlN/GaN high power devices: origin and impact on contact breakdown and IV characteristics. J. Appl. Phys. 2011;109:063720. doi: 10.1063/1.3552932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kobayashi M, et al. Unveiling the impurity band induced ferromagnetism in the magnetic semiconductor (Ga,Mn)As. Phys. Rev. B. 2014;89:205204. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.89.205204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krieger JA, et al. Spectroscopic perspective on the interplay between electronic and magnetic properties of magnetically doped topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B. 2017;96:184402. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.96.184402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Man MKL, et al. Imaging the motion of electrons across semiconductor heterojunctions. Nat. Nanotech. 2017;12:36–40. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2016.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strocov VN, et al. Soft-X-ray ARPES facility at the ADRESS beamline of the SLS: concepts, technical realisation and scientific applications. J. Synchrotron Rad. 2014;21:32–44. doi: 10.1107/S1600577513019085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strocov VN, et al. High-resolution soft X-ray beamline ADRESS at the Swiss Light Source for resonant inelastic X-ray scattering and angle-resolved photoelectron spectroscopies. J. Synchrotron Rad. 2010;17:631–643. doi: 10.1107/S0909049510019862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Braun J, et al. Exploring the XPS limit in soft and hard x-ray angle-resolved photoemission using a temperature-dependent one-step theory. Phys. Rev. B. 2013;88:205409. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.88.205409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giannozzi P, et al. Quantum expresso: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2009;21:395502. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/21/39/395502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yue Y, et al. InAlN/AlN/GaN HEMTs with regrown ohmic contacts and fT of 370 GHz. IEEE Electron Dev. Lett. 2012;33:988–990. doi: 10.1109/LED.2012.2196751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mayboroda I, et al. Selective MBE growth of nonalloyed ohmic contacts to 2D electron gas in high-electron-mobility transistors based on GaN/AlGaN heterojunctions. Tech. Phys. Lett. 2014;40:488–490. doi: 10.1134/S1063785014060091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request. The SX-ARPES data were processed using the custom package MATools available at https://www.psi.ch/sls/adress/manuals.