Summary

Breeding for disease resistance is the most effective strategy to control diseases, particularly with broad‐spectrum disease resistance in many crops. However, knowledge on genes and mechanism of broad‐spectrum resistance and trade‐off between defence and growth in crops is limited. Here, we show that the rice copine genes OsBON1 and OsBON3 are critical suppressors of immunity. Both OsBON1 and OsBON3 changed their protein subcellular localization upon pathogen challenge. Knockdown of OsBON1 and dominant negative mutant of OsBON3 each enhanced resistance to rice bacterial and fungal pathogens with either hemibiotrophic or necrotrophic lifestyles. The defence activation in OsBON1 knockdown mutants was associated with reduced growth, both of which were largely suppressed under high temperature. In contrast, overexpression of OsBON1 or OsBON3 decreased disease resistance and promoted plant growth. However, neither OsBON1 nor OsBON3 could rescue the dwarf phenotype of the Arabidopsis BON1 knockout mutant, suggesting a divergence of the rice and Arabidopsis copine genes. Our study therefore shows that the rice copine genes play a negative role in regulating disease resistance and their expression level and protein location likely have a large impact on the balance between immunity and agronomic traits.

Keywords: rice immunity, bacterial blight, blast, sheath blight, growth, trade‐off

Introduction

Nearly half of the world population consumes rice (Oryza sativa L.) as the staple food. However, rice grain production and quality are severely threatened by a variety of pathogens, including hemibiotrophic Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) and Pyricularia oryzae/Magnaporthe oryzae (M. oryzae), and necrotrophic Rhizoctonia solani (R. solani). These three pathogens respectively cause bacterial leaf blight, fungal blast and sheath blast, three devastating diseases of rice. Broad‐spectrum and durable resistance is an effective strategy to control disease in rice (Deng et al., 2017). Recent studies have characterized dozens of genes contributing to disease resistance and provided potential solutions for the control of diseases in rice. However, much remains unknown on the rice immune machinery. In particular, how the dynamic immunity and the trade‐off between defence and growth are controlled remains elusive in the crop that has been extensively domesticated.

Rice has evolved a complex innate immune machinery during its long co‐evolution with pathogens. Recent advances in genetic and genomic studies have greatly contributed to a better understanding of the complexity of the rice–Xoo and rice–M. oryzae pathosystems (Niño‐Liu et al., 2006; Valent and Chumley, 1991; Wilson and Talbot, 2009). It is proposed that the two‐layered innate immunity responses mainly established in Arabidopsis thaliana (referred to as Arabidopsis) (Dangl and Jones, 2001; Jones and Dangl, 2006) also work in rice. The first layer of innate immunity is activated upon detection of conserved pathogen‐associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or microbe‐associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) by cell surface pattern‐recognition receptors (PRRs), resulting in PAMP‐triggered immunity (PTI). The second layer of innate immunity is activated upon recognition of pathogen‐secreted effectors by intracellular receptors, namely disease resistance (R) genes, leading to effector‐triggered immunity (ETI). It has been generally recognized that PTI is conserved in diverse plant species and acts as a major determinant of basal defence against diverse pathogens. In contrast, ETI provides a race‐specific protection against pathogens with a stronger defence reaction than PTI, often accompanied by rapid programmed cell death at the infection site, namely hypersensitive response (Coll et al., 2011). A number of PRRs, mainly receptor‐like kinases (RLKs) and receptor‐like proteins (RLPs), are shown to recognize PAMPs from rice pathogens. For instance, the rice RLP CEBiP and RLK CERK1 can recognize fungal chitins and induce defence responses (Kaku et al., 2006; Shimizu et al., 2010). For ETI in rice, a large number of effectors have been identified from M. oryzae and Xoo and dozens have been characterized in terms of their secretion, virulence and the recognition by rice host (Valent and Khang, 2010). Many R proteins have been identified in rice, particularly those conferring broad‐spectrum disease resistance (Liu et al., 2013; Verdier et al., 2012). Activation of these R proteins induces robust defence responses usually including reactive oxygen species (ROS) production to effectively limit pathogen growth. Interestingly, a pair of antagonistic NLR receptors PigmR and PigmS were epigenetically regulated to fine‐tune durable and broad‐spectrum blast resistance and yield phenotypes in rice (Deng et al., 2017).

In the model plant Arabidopsis, the calcium‐binding proteins BON1, BON2 and BON3 are shown to be negative regulators of plant disease resistance (Yang and Hua, 2004; Yang et al., 2006). They belong to the evolutionarily conserved copine proteins found in protozoa, plants, nematodes and mammals (Creutz et al., 1998). Copine proteins have two calcium‐dependent phospholipid‐binding C2 domains at their amino (N)‐terminus and a putative protein–protein interaction vWA (von Willebrand A) at their carboxyl (C)‐terminus (Rizo and Sudhof, 1998; Whittaker and Hynes, 2002). The BON1 protein resides on the plasma membrane, and this is mainly through myristoylation at its second residue glycine (Hua et al., 2001; Li et al., 2010). It has conserved aspartate (Asp) residues important for calcium binding in the two C2 domains. These Asp residues are essential for BON1 function, suggesting a regulation by calcium of BON1 (Li et al., 2010). The loss‐of‐function mutant bon1‐1 in Col‐0 accession has an enhanced disease resistance to virulent bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pst) DC3000 and oomycete pathogen Hyaloperonospora parasitica (Yang and Hua, 2004). This enhanced resistance largely results from an up‐regulation of the plant immune receptor NLR gene SNC1 in the absence of pathogen infection (Li et al., 2007; Yang and Hua, 2004). The autoimmune phenotype of bon1 exhibited at normal growth temperature 22 °C can be suppressed at relatively high temperature 28 °C, due to the temperature‐sensitive nature of the NLR proteins (Zhu et al., 2010). The three members of BON1 gene family (BON1, BON2 and BON3) in Arabidopsis are all suppressors of immunity, and their triple mutants die from heightened defence responses (Yang et al., 2006). Intriguingly, the bon1 mutants did not close stomata in response to calcium, ABA or bacterial pathogen (Gou et al., 2015). Stomata are the entry point of many bacterial pathogens, and their closure upon recognition of PAMP signals is one critical defence mechanism (Melotto et al., 2006). BON1 is therefore a positive regulator of stomatal closure in Arabidopsis at the pre‐invasion phase, and this function in stomatal closure regulation is independent of its role in regulating NLR gene expression (Gou et al., 2015).

Rice also has two BON1 homologous proteins, with OsBON1 closely related to BON1 and OsBON3 to BON3 (Zou et al., 2016). The functions of BON1‐like or copine proteins in rice and other monocots remain unknown. Here, we identified OsBON1 and OsBON3 as negative regulators of disease resistance to Xoo, M. oryzae and R. solani. Transcription of OsBON1 and OsBON3 is constitutively activated in the rice autoimmunity mutant ebr1 (enhanced blight and blast resistance 1) and inducible by pathogen infection. The enhanced resistance in OsBON mutants is associated with a trade‐off in growth. The OsBON1‐mediated defence activation and growth trade‐off are largely suppressed by high temperature. Intriguingly, neither OsBON1 nor OsBON3 was capable to complement the Arabidopsis bon1 mutant. Our study reveals a nonredundant or partitioning function of BON/copine proteins in plant innate immunity in Arabidopsis and rice, two model plants that have evolved independently.

Results

OsBON1 and OsBON3 are induced by Xoo infection

In our previous study on the broad‐spectrum disease resistance mutant ebr1 (Wang et al., 2005; You et al., 2016), we observed that OsBON1 (Os02g0521300) and OsBON3 (Os05g0373300) were up‐regulated in ebr1 compared with the wild type. Our previous study showed that both OsBON1 and OsBON3 were induced by M. oryzae (Zou et al., 2016). The induction of these two genes was also observed during Xoo infection. The expression of both OsBON1 and OsBON3 was greatly increased by Xoo challenging compared with water mock inoculation (Figure 1a,b). Notably, the relative expression level of OsBON3 was lower than that of OsBON1 in all tissue samples (Figure S1a,b). This induction pattern suggests that OsBON1 and OsBON3 might play roles in rice immunity.

Figure 1.

Induction of OsBON1 and OsBON3 by Xoo and characterization of OsBON1‐RNAi and overexpression transgenic plants. (a,b) Induction of OsBON1 (a) and OsBON3 (b) RNA expression by Xoo. Two‐month‐old plants were inoculated by Xoo (strain PXO99A), with mock inoculation (leaf‐clipping with water). Total RNAs were isolated from the inoculated leaves at different time points. Shown are transcript levels of OsBON1 and OsBON3 detected by qRT‐PCR. (c–e) RNA expression levels of OsBON1 (c,e) and OsBON3 (d) in representative lines of OsBON1‐ RNAi (c), OsBON1‐RNAi (d) and OsBON1‐OE (e) compared to the wild‐type TP309 detected by qRT‐PCR. (f) Protein levels of OsBON1 in independent transgenic lines and the wild type detected by Western blot using an anti‐OsBON1 antibody. OsACTIN was used as a control. The rice OsActin1 gene was used as an internal control to normalize expression levels for qRT‐PCR (a–e). Data are shown as means ± SD from three biological replicates (Student's t‐test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001) (a–c and e).

Quantitative RT‐PCR (qRT‐PCR) analysis showed that OsBON1 and OsBON3 transcripts were present in different tissues, with partially overlapping expression patterns. OsBON1 was more predominantly expressed in leaves (Figure S1a,b). We subsequently generated reporter transgenes using the promoters of OsBON1 and OsBON3 to drive β‐glucuronidase (GUS) expression, respectively. GUS staining of transgenic plants of pOsBON1::GUS and pOsBON3::GUS revealed that both OsBON1 and OsBON3 were expressed in the embryo and OsBON3 was expressed in the coleoptile (Figure S1c,d). At heading stage, OsBON1 and OsBON3 expression could be detected in almost all the tissues. High GUS expression was found in young and mature leaves as well as junction of leaf and leaf sheath in OsBON1::GUS transgenic lines. High GUS activity was found in junction of leaf and leaf sheath, node region and leaf sheath in OsBON3::GUS transgenic lines (Figure S1c,d).

OsBON1 negatively regulates rice resistance to bacterial pathogen Xoo

To determine the function of OsBON1 in rice immunity, we obtained transgenic lines with either reduced or increased expression of OsBON1 in TP309 background. The reduced expression was achieved by RNA interference (RNAi), and the lower expression of OsBON1 but not OsBON3 in OsBON1‐RNAi lines was verified by qRT‐PCR (Figure 1c,d). The overexpression was achieved by expressing either OsBON1 or the OsBON1‐eGFP fusion gene under the promoter of the maize Ubi promoter. The RNA expression of OsBON1 in OsBON1‐OE lines was 5‐ to 50‐fold that of the wild type as analysed by qRT‐PCR (Figure 1e). To further characterize the OsBON1 protein levels in transgenic lines, we performed Western blot using antibodies against OsBON1 (Figure 1f). OsBON1 protein could not be detected in the RNAi lines while it was five‐ to eightfold more in the OsBON1‐OE lines compared to the wild type. The OsBON1‐eGFP lines also had a higher expression of OsBON1 protein with over 20‐fold increase compared to the wild type (Figure 1f).

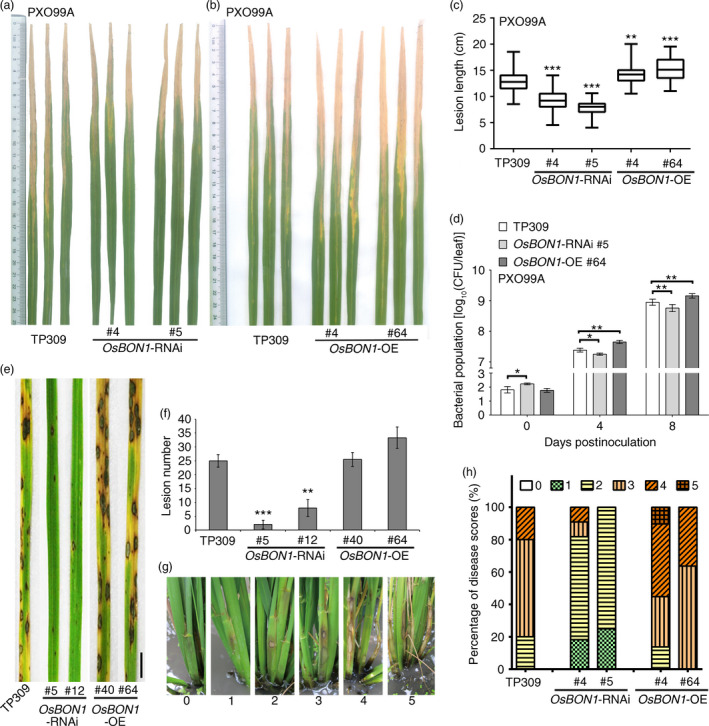

We used two stable RNAi lines (#4 and #5) and two stable overexpression lines (#40 and #64) for disease resistance evaluation. We found that the OsBON1‐RNAi lines exhibited an enhanced resistance to the Xoo strain PXO99A, while OsBON1‐OE lines exhibited an increased susceptibility. OsBON1‐RNAi had significantly shorter lesions and OsBON1‐OE lines had significantly longer lesions than the wild‐type TP309 (Figure 2a–c). OsBON1‐RNAi and OsBON1‐OE lines were also inoculated with Xoo strains PXO71 and PXO347 and similar disease resistance results was observed as inoculated with the Xoo strain PXO99A (Figure S2a–d). Disease resistance was also calculated by bacterial growth in the leaves at 0, 4 and 8 days postinoculation (dpi). The colony‐forming units (cfu) of Xoo strain PXO99A was reduced in OsBON1‐RNAi and increased in OsBON1‐OE plants compared to the wild type (Figure 2d). Similar to OsBON1‐OE transgenic lines, OsBON1‐eGFP lines were also more susceptible to Xoo strain PXO99A (Figure S3a,b). Therefore, OsBON1 plays a negative role in rice basal disease resistance against the bacterial pathogen.

Figure 2.

OsBON1 negatively regulates disease resistance to Xoo and fungal pathogens M. oryzae and R. solani. Shown are disease resistance phenotypes to Xoo (a–d), M. oryzae (e,f) and R. solani (g,h) in OsBON1‐RNAi and OsBON1‐OE lines. (a,b)Disease symptoms of OsBON1‐ RNAi (a) and OsBON1‐OE lines compared with wild‐type TP309 at 14 dpi with Xoo strain PXO99A. (c) Lesion lengths of OsBON1‐ RNAi and OsBON1‐OE lines compared with wild‐type TP309 at 14 dpi with Xoo strain PXO99A. Data are shown as box plots (n ≥ 50). (d) Xoo strain PXO99A bacterial populations per leaf were measured at 0, 4 and 8 dpi. Values are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). The bacterial growth curve experiment was repeated twice with similar results. (e) Disease symptoms of the wild‐type TP309, OsBON1‐RNAi lines and OsBON1‐OE lines at 7 dpi with M. oryzae (isolate Hoku1). Scale bars = 2 cm. (f) Average lesion number per leaf of TP309, OsBON1‐RNAi lines and OsBON1‐OE lines at 7 dpi with M. oryzae. Values are means ± SD (n ≥ 30). This experiment was repeated independently at least three times with similar results. (g) Disease scores (from 0 to 5) used in sheath blight resistance at 14 dpi with R. solani AG1‐IA isolate RH‐9. (h) Disease profiles of sheath blight expressed as percentages of six disease scores in TP309, OsBON1‐RNAi and OsBON1‐ OE lines at 14 dpi. Lesion length (c) was measured independently for at least three generations with similar results. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences in comparison with the wild‐type control (Student's t‐test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). Note that the knockdown and overexpression of OsBON1 significantly increased and decreased Xoo resistance, respectively.

OsBON1 negatively regulates resistance to M. oryzae

We then analysed the role of OsBON1 in resistance to rice blast (M. oryzae). The wild‐type TP309 and OsBON1 transgenic plants were assayed for resistance to virulent M. oryzae isolate Hoku1 at seedling stage by spray inoculation. Because seeds produced from glasshouse‐grown plants were limited, we performed blast inoculation using additional RNAi line 12 in addition to line 5. The two representative OsBON1‐RNAi lines strongly exhibited enhanced blast resistance at 7 dpi, with 3 and 7 lesions per leaf on average on OsBON1‐RNAi #5 and #12, respectively, which was significantly reduced compared to the 25 lesions in the wild‐type TP309 (Figure 2e,f). The overexpression of OsBON1 also increased disease severity because more typical susceptible lesions developed on the OsBON1‐OE plants (Figure 2e,f). We further investigated the progressiveness of invasive hyphal growth in leaf sheath with virulent isolate Hoku1. The progressiveness of invasive hyphal growth of M. oryzae can be rated by types/stages I–IV as described previously (Kankanala et al., 2007): type I, the initial stage of spore germination, germ tube not yet formed; type II, the spores germinated, forming the appressorium (AP); type III, successful invasion of the host cell and formation of primary hyphae (PH); and type IV, hyphae continuing to invade and forming secondary/branch invasive hyphae (BH). We observed that 48% and 31% of penetration sites were type III and type IV, respectively, inside the epidermal cells of the wild‐type TP309 at 38 hpi (Figure S4a). By contrast, only 34%–35% of penetration sites were type III and 15%‐17% were type IV in the two OsBON1‐RNAi lines (Figure S4a). Growth of the infectious hyphae was also analysed by Uvitex 2B staining, and a similar inhibition of the hyphae growth was observed in the OsBON1‐RNAi lines (Figure S4b‐f). Therefore, the development of advanced infectious phases of blast fungus was drastically delayed in OsBON1‐RNAi plants. Although OsBON1‐OE lines were indistinguishable from the wild type in M. oryzae lesion numbers and infection stage because the wild‐type TP309 is susceptible to M. oryzae, more typical susceptible lesions that developed on the OsBON1‐OE plants revealed that OsBON1‐OE plants had severer disease symptom than the wild type.

OsBON1 negatively regulates resistance to necrotrophic fungal pathogen R. solani

To test whether OsBON1 also conditions resistance against necrotrophic pathogens, we performed inoculation experiments with R. solani. In contrast to the hemibiotrophic pathogens M. oryzae and Xoo that invade living rice cells, R. solani kills host cells at very early stages of infection (De Vleesschauwer et al., 2013). In nature, R. solani survives as sclerotia on plant residues in soil (Jia et al., 2013), and therefore, we applied field evaluation to measure resistance against R. solani for three generations. Two‐month‐old rice plants grown in the paddy field were inoculated, and the degree of disease severity was scored on sheath at 14 dpi giving a value of 0–5 as described (Park et al., 2008). A value of 0 represents no lesion; 1 represents the appearance of water‐soaked lesion; 2 represents the appearance of necrotic lesion; 3 represents less than 50% necrosis on the leaf sheath; 4 represents more than 50% necrosis on the leaf sheath; and 5 represents necrosis across the entire leaf sheath resulting in death (Figure 2g). Based on the scores of two independent lines for each transgene, OsBON1‐OE lines were found to be more susceptible and OsBON1‐RNAi lines more resistant to R. solani than the wild type (Figure 2h). OsBON1‐eGFP transgenic lines were also sensitive to R. solani, similar to OsBON1‐OE lines (Figure S3c). Therefore, OsBON1 also negatively regulates disease resistance to the necrotrophic fungus R. solani.

OsBON1 and OsBON3 do not complement the Arabidopsis bon1 mutant

The Arabidopsis BON1 gene is also a negative regulator of disease resistance, and we asked whether the rice BON genes could complement the Arabidopsis bon1 defect. However, unlike the Arabidopsis BON3 gene that rescued the bon1 mutant when overexpressed (Yang et al., 2006), neither OsBON1 nor OsBON3 rescued the Arabidopsis bon1 mutant phenotype when they were overexpressed (Figure S5a). Transcript levels of OsBON1 and OsBON3 were detected in transgenic Arabidopsis (Figure S5b,c). OsBON1 accumulation was also detected in transgenic Arabidopsis plants (Figure S5d). This suggests that OsBON genes might have diverged from the Arabidopsis BON1 gene during evolution, given that some amino acids in the conserved C2 and vWA domains in OsBON proteins are different from their Arabidopsis homologs (Zou et al., 2016).

Loss of OsBON1 function leads to enhanced defence activation

Activation of plant defence responses during pathogen infection is accompanied by defence hormone pathways, such as salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonate (JA), and up‐regulation of pathogenesis‐related (PR) genes (van Loon et al., 2006). The PR genes PR1a and PR4 are marker genes of SA and JA pathway activation, respectively (Agrawal et al., 2000, 2001; Wang et al., 2011). We therefore analysed PR gene expression in OsBON1‐RNAi and OsBON1‐overexpressing plants during a time course of 0–48 h in leaves inoculated with Xoo (PXO99A). As expected, pathogen challenge strongly induced the expression of PR1a in the wild type (Figure 3a). In OsBON1‐RNAi plants, PR1a was constitutively expressed and was further induced to higher levels than in the wild‐type plants (Figure 3a). PR4 was not constitutively expressed but was induced by Xoo to a higher level in OsBON1‐RNAi plants than in the wild type (Figure 3b). In contrast, OsBON1 overexpression lines had much lower induction of PR1a upon Xoo challenge (Figure 3a,b). We did not observe significant differences in SA or JA levels among the wild type, OsBON1‐RNAi plants and OsBON1 overexpression plants (Figure S6a‐d). Therefore, the loss of OsBON1 function likely resulted in enhanced defence activation of both SA and JA responses, but not SA and JA levels because rice has high endogenous SA and JA levels as previously proposed (Yuan et al., 2007). A similar synchronous activation of SA and JA was also observed in other rice immunity mutants (Tong et al., 2012; You et al., 2016).

Figure 3.

OsBON1 affects expression of rice defence‐responsive genes. RNA expression of PR1a (a) and PR4 (b) was detected in 2‐month‐old OsBON1‐RNAi and OsBON1‐OE transgenic and wild‐type TP309 before and after inoculation with Xoo PXO99A. The OsActin1 gene was used as an internal control, and expression levels were normalized to 0 h of TP309. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant difference in comparison with the wild‐type plants (Student's t‐test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

OsBON1 promotes rice growth and development

The transgenic lines of OsBON1‐RNAi and OsBON1‐OE exhibited additional growth phenotypes in tiller number and plant height. At the age of 2 months, compared to the wild‐type TP309, OsBON1‐RNAi transgenic lines had fewer tillers (Figure 4a,b), while OsBON1‐OE transgenic lines had increased tiller number (Figure 4c,d). At mature stage, OsBON1‐RNAi lines had decreased plant height compared to the wild type (Figure 4e,f), while OsBON1‐OE lines had increased plant height (Figure 4e,f). These data indicate that OsBON1 is a positive regulator of plant growth and functions in trade‐off between defence and growth fitness.

Figure 4.

OsBON1 promotes rice growth and development. (a,b) Morphology (a) and tiller number (b) of 2‐month‐old TP309 and OsBON1‐RNAi plants. (c,d) Morphology (c) and tiller number (d) of 2‐month‐old TP309 and OsBON1‐OE plants. (e,f) Morphology (e) and plant height (f) of TP309, OsBON1‐RNAi and OsBON1‐OE mature plants. Data on tiller number and plant height are shown as box plots (n ≥ 30). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences in comparison with the wild‐type control (Student's t‐test, ***P < 0.001) (b, d and f). Scale bars = 20 cm (a, c and e).

High temperature suppresses the mutant phenotype of OsBON1‐RNAi

In Arabidopsis, the loss‐of‐function bon1 mutants display a temperature‐dependent defence response (Yang and Hua, 2004), which was attributed to the temperature sensitivity of TIR‐NB‐LRR genes (Zhu et al., 2010). Another study also showed that high temperature attenuated the effectiveness of many rice R genes against Xoo, and Xoo was more virulent at high temperature (Webb et al., 2010). To test whether the OsBON1‐mediated growth and defence activation are also affected by temperature, we compared the growth phenotypes of 2‐week‐old OsBON1‐RNAi lines and expression of the defence marker gene PR1a in the OsBON1‐RNAi lines grown at high temperature (32 °C) and normal growth temperature (26 °C). Indeed, temperature sensitivity was observed in the OsBON1‐RNAi lines and in the wild type. The dwarf growth phenotype of 2‐week‐old OsBON1‐RNAi plants exhibited at 26 °C was not observed at 32 °C (Figure 5a–d). We further analysed the expression of the PR1a genes at two temperatures and found that in contrast to the up‐regulation at 26 °C, the expression levels of PR1a in OsBON1‐RNAi lines were similar to those of the wild type at 32 °C (Figure 5e,f). This suggests that high temperature likely inhibits the immune activation in the OsBON1‐RNAi lines.

Figure 5.

High temperature inhibits the stunted growth phenotype and PR1a overexpression of OsBON1‐RNAi plants. (a,b) Morphology of 2‐week‐old TP309 and OsBON1‐RNAi plants grown at 26 °C (a) and 32 °C (b). Note that the 32 °C growth inhibited the dwarfing of OsBON 1‐RNAi plants. Scale bars = 8 cm. (c,d) Plant heights of TP309 and OsBON1‐RNAi lines grown at 26 °C (c) and 32 °C (d). Data are means ± SD (n ≥ 20). No significant difference was detected at 32° C. (e,f) Expression levels of OsPR1a revealed by qRT‐PCR in the wild‐type TP309 and OsBON1‐RNAi lines at 26 °C (e) and 32 °C (f). The OsActin1 gene was used as an internal control. Note that the constitutive activation of OsPR1a in the OsBON1‐RNAi lines was compromised under high temperature (32 °C). No significant difference was detected at 32 °C. Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference in comparison with the wild‐type control (Student's t‐test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01) (c and e).

OsBON3 negatively regulates disease resistance and cell death

To determine the function of OsBON3, we attempted to generate OsBON3‐RNAi transgenic lines but were unable to obtain transformants with decreased expression of OsBON3. Instead, we generated OsBON3 overexpression plants by driving its expression under the maize Ubi promoter (OsBON3‐OE). Similar to the OsBON1‐OE lines, the OsBON3‐OE displayed vigorous growth with increased height and more tillers than the wild type (Figure S7a,b). These plants also exhibited a decreased disease resistance to Xoo (Figure 6b–d). Therefore, OsBON3, similar to OsBON1, antagonistically regulates rice disease resistance and growth.

Figure 6.

OsBON3 negatively regulates rice disease resistance. (a) Protein levels of OsBON3 in representative OsBON3‐OE and OsBON3‐eGFP transgenic lines and wild types detected by Western blot using an anti‐BON3 antibody. (b) Disease symptoms of OsBON3‐OE lines in comparison with the wild‐type NIP at 14 dpi with Xoo PXO99A. (c) Lesion lengths of OsBON3‐OE and NIP at 14 dpi with Xoo PXO99A. Data are shown in box plots (n ≥ 50). (d) Bacterial growth measured at 0, 4 and 8 dpi with Xoo PXO99A. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). The bacterial growth curve experiment was repeated twice with similar results. (e) Lesion mimic phenotype of 12‐week‐old OsBON3‐eGFP plants. Scale bars = 1 cm. (f) DAB staining of H2O2 accumulation in twelve‐week‐old OsBON3‐eGFP leaves. Scale bars = 1 cm. (g,h) Disease resistance of OsBON3‐eGFP lines compared with the wild type at 14 dpi with Xoo PXO99A. Shown here are disease symptoms (g) and lesion length (h). Lesion length (h) data are shown as box plots (n ≥ 50). Lesion length measurement was repeated independently for 3 generations with similar results. Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference in comparison with the wild‐type control (Student's t‐test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001) (c,d and h).

Unexpectedly, overexpression of the OsBON3‐eGFP fusion displayed a semidwarf and lower tillering phenotype similar to that of OsBON1‐RNAi (Figure S7c). RNA and protein blot assays showed the accumulation of both OsBON3 transcripts (Figure S7d) and OsBON3‐eGFP protein (Figure 6a) in the OsBON3‐eGFP lines. This indicates that they are unlikely RNA‐silenced plants but rather dominant negative lines of OsBON3. In addition to the growth defects, the OsBON3‐eGFP lines displayed a spontaneous lesion mimic phenotype late at booting stage (Figure 6e). This cell death phenotype was associated with high H2O2 accumulation in the absence of pathogen (Figure 6f). These OsBON3‐eGFP lines also exhibited an enhanced disease resistance to Xoo (Figure 6g,h). The enhanced resistance was associated with the development of lesion mimics because the enhanced resistance was not observed at seedling and tillering stages when lesions were not developed. Therefore, OsBON3, similar to OsBON1, plays a negative role in immunity and promotes growth in rice.

Subcellular localization of OsBON1 and OsBON3 is affected by pathogen infection

A number of signalling events occur upon pathogen infection at the plasma membrane where the Arabidopsis BON1 is localized. To determine the location of OsBON1 and OsBON3, we generated their YFP fusion proteins OsBON1‐YFP and OsBON3‐YFP driven by the 35S promoter and transiently expressed them in rice protoplasts and Nicotiana benthamiana (N. benthamiana). The YFP fluorescence signals were concentrated on the plasma membrane in both expression systems (Figure 7a). Stable transgenic lines of the OsBON1‐eGFP and OsBON3‐eGFP were also generated, and the GFP fluorescence signals were also detected on the plasma membrane in root tip cells (Figure 7b). OsBON1 and OsBON3 are predicted to be calcium‐dependent lipid‐binding proteins (Li et al., 2010). We therefore determined whether or not the putative calcium‐binding sites are critical for the plasma membrane association of OsBON1 and OsBON3. However, mutating aspartates that are thought to be critical for calcium binding in the OsBON1 or OsBON3 did not alter their locations (Figure S8a–c).

Figure 7.

Pathogen infection alters subcellular localization of OsBON1 and OsBON3. (a) Fluorescence signals of OsBON1‐YFP and OsBON3‐YFP expressed in rice protoplasts and N. benthamiana leaves. Both proteins are mainly localized to the plasma membrane in contrast to the control protein YFP. Scale bars, 10 μm (rice protoplasts) or 50 μm (tobacco leaves). (b) Fluorescence signals of OsBON1‐YFP and OsBON3‐YFP in root cells of stable transgenic lines of Ubi::OsBON1‐eGFP and Ubi::OsBON3‐eGFP. Plasmolysis was induced using 30% sucrose. Scale bars = 50 μm. (c) Localization of OsBON1‐eGFP protein after infection by Xoo. Roots of OsBON1‐eGFP seedlings were infected with Xoo or mock‐inoculated with water. Shown are confocal images taken at 48 hpi. Scale bars = 50 μm. (d) Localization change of OsBON1‐eGFP during M. oryzae infection. Shown are laser confocal images taken at 0 h (control) and 36 h after leaf sheath inoculation with M. oryzae. The transgenic plants with the plasma membrane‐located OsAnn‐eGFP were used as a control. Arrows indicate biotrophic interfacial complex (BIC). Scale bars = 20 μm.

As membrane dynamics is important for plant immunity, we asked whether or not the BON proteins change their localization upon pathogen challenge. We adopted a root inoculation approach (Chen et al., 2010) to analyse the dynamics of OsBON localization after Xoo infection. In contrast to the sharp and even signals on plasma membrane observed before infection, the OsBON1‐GFP signal became diffused with punctate aggregations both on the plasma membrane and in the cytoplasm after root infection (Figure 7c). A similar internationalization was also observed for OsBON3‐eGFP after root inoculation with Xoo (Figure S9). In addition, we used OsBON1‐eGFP lines to observe OsBON1 localization after infection with M. oryzae using sheath inoculation (Figure 7d). The OsBON1‐eGFP protein was found to relocate to the plasma membrane around fungal haustoria and appeared to be enriched at a special structure named BIC (biotrophic interfacial complex), which is thought to be the secretion site of pathogen effectors (Khang et al., 2010). In contrast, the eGFP fusion with a control plasma membrane protein OsAnn‐eGFP did not change the plasma membrane location upon fungal infection (Figure 7d). These results together indicate that pathogen infection triggers relocalization of OsBON1 and OsBON3, which may serve as an early response to pathogen invasion.

Discussion

Copines are evolutionarily conserved calcium‐binding proteins widely found in protozoa, plants and animals, and their functions have remained largely enigmatic. Our earlier studies have showed that all three Arabidopsis copine genes, BON1, BON2 and BON3, are negative regulators of plant immune responses (Yang and Hua, 2004; Yang et al., 2006). The loss of BON1 leads to enhanced resistance to bacterial pathogen P. syringae and oomycete pathogen H. parasitica in Arabidopsis (Yang and Hua, 2004). The impact of BON1 on immunity is mediated partially through suppressing the expression of the plant immune receptor NB‐LRR genes. Some of these NB‐LRR genes are accession (ecotype)‐specific, which raised questions of whether or not the immunity function observed in Arabidopsis is a conserved function of copine or BON genes of all plants or a unique phenomenon in Arabidopsis. Our current study revealed an important role of rice copine or BON genes in immunity. An enhanced and broad‐spectrum disease resistance is found in the RNAi lines of OsBON1 as well as dominant negative lines of OsBON3 in rice, suggesting a conserved role of copines as suppressors or negative regulators of immunity in higher plants. It is notable that the rice OsBON genes could not rescue the bon1 mutant phenotype in Arabidopsis. Therefore, copine proteins might have subjected to species‐specific functionality and lost the interexchange capacity in immune responses among higher plants. However, this hypothesis awaits further investigation on additional copine genes in other plants.

Interestingly, knocking down OsBON function enhances resistance to both hemibiotrophic (Xoo and M. oryzae) and necrotrophic (R. solani) pathogens in rice. In Arabidopsis, the bon1 mutant has enhanced resistance to biotrophic and hemibiotrophic pathogens, and its resistance to necrotrophic pathogens has not been tested. It is often assumed that an enhanced resistance to biotrophic pathogens is accompanied by a compromised resistance to necrotrophic pathogens probably due to the antagonistic interaction of SA and JA signalling (Spoel and Dong, 2008). Therefore, it came as a surprise that the OsBON1‐RNAi lines exhibit resistance to both hemibiotrophic and necrotrophic fungi. The mechanism of such enhanced resistance is not fully understood. It is evident that knockdown of OsBON confers a higher basal expression of defence response genes such as PR1 and PR4 and a higher induction of these genes by Xoo in rice (Figure 3). However, no significant change was found for the SA or JA levels in the OsBON mutants (Figure S6), in contrast to a higher level of SA in the Arabidopsis bon1 mutant. Our study here suggests that the resistance to both biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens is at least partially due to the slowing of the fungal invasion in the mutants. In OsBON1‐RNAi lines, the development of hyphae was inhibited at early phase (Figure S4). The inhibition was not complete as some hyphae went on to develop further and invade the plants. This could be due to the presence of OsBON3 function or residual function of OsBON1 in the RNAi lines. Further analysis of the double‐knockout mutant will reveal whether the OsBON function is absolutely required for the invasion of fungal pathogens. Nevertheless, the effect on pathogen entry might be a shared mechanism in resistance against biotrophic and necrotrophic fungi in later phase, given that defence‐related genes regulated by both SA and JA signalling are constitutively or more rapidly induced in the OsBON1‐RNAi lines (Figure 3), which may provide an explanation of broad‐spectrum disease resistance to both biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens in OsBON1‐RNAi. Similar to OsNPR1 (Li et al., 2016), OsBON1 might modify signalling of SA and JA rather than their levels as rice has high basal levels of SA and JA.

This study also reveals a different functional partitioning among members within the copine gene family between Arabidopsis and rice. Like other monocots analysed, rice has two copine genes, with OsBON1 in clade I and OsBON3 in clade III. The clade I copine gene in Arabidopsis is duplicated into BON1 and BON2, and like all other dicots analysed, Arabidopsis has one copine gene, BON3, in clade III. In Arabidopsis, the loss of BON1 function leads to autoimmune phenotype, while the loss of BON2 or BON3 alone does not lead to obvious immune activation. However, the simultaneous loss of BON1 and BON2, or BON1 and BON3 but not BON2 and BON3, leads to stronger autoimmunity than the loss of single BON1. This indicates that BON1 has a major role in immunity regulation, while BON2 and BON3 have overlapping functions with BON1. In rice, the reduction of OsBON1 or OsBON3 dominant negative regulation each leads to enhanced disease resistance. Although the exact contribution of these two rice genes still awaits the analysis of knockout mutants, the lesion mimic phenotype in the OsBON3 mutant suggests a larger or stronger role of OsBON3 in immunity and/or hypersensitive cell death than the OsBON1. It thus appears that individual copine genes within a species underwent functional partition in modulating immunity, such that Arabidopsis BON1 assumes a more dominant role while the rice OsBON1 and OsBON3 maintain a relatively equal partition. It is likely that clade I and clade III BON genes have distinct functions besides overlapping functions, which would also explain their presence in all plant species analysed, and no complementation of OsBON1 or OsBON3 with the Arabidopsis bon1 mutant. The lesion mimic phenotype is seen in the mutant of OsBON3 but not that of OsBON1, also suggesting a distinct function of OsBON3 if not a higher activity of OsBON3.

This study also sheds some lights on the mechanism of how plant copines modulate immune responses. Most strikingly, both OsBON1 and OsBON3 proteins change their localizations upon pathogen invasion. The OsBON1 and OsBON3 proteins form punctate aggregates in the PM and cytosol after Xoo infection, while it is concentrated at interface between the host cell and fungal hypha during M. oryzae infection. Protein localization changes have been reported for signalling molecules. For instance, the FLS2 and XA21 receptors undergo endocytosis and move from the PM to endosomes (Chen et al., 2010; Robatzek et al., 2006). Recently, the rice Rac1‐RbohB/H immune complex was reported to move to microdomains upon pathogen invasion (Nagano et al., 2016). The immediate change of protein localization indicates that OsBON proteins are also involved in the early event of plant immune responses, either facilitating the signalling to enhance immune responses or antagonizing the signalling to prevent overactivating immune responses. Current evidence could not resolve between the activating and inhibiting models. In the activating model, OsBON proteins might become targets of pathogen effectors and the loss of their functions may be recognized by plants as pathogen invasion signals and thus trigger immune responses. This is consistent with the finding of the involvement of NB‐LRR genes in autoimmunity of the bon1 mutants that are temperature‐dependent. Whether the enhanced resistance in rice bon mutants involves NB‐LRR genes is not known yet, but the temperature sensitivity of the growth defect and PR gene expression suggests an involvement of such genes in rice as well. However, the inhibiting model cannot be excluded. The induction of these genes upon pathogen invasion could be a fine‐tuning mechanism in preventing overactivating immune responses in response to pathogens and autoimmunity in the absence of pathogens. Therefore, their loss of function results in higher activation of immune signalling to confer resistance to normally virulent pathogens as observed in the immune homoeostasis controlled by the rice EBR1‐OsBAG4 module (You et al., 2016).

A growth‐promoting function of OsBON1 and OsBON3 was observed in their overexpression plants. Trade‐off is often observed between growth and defence, and devoting less in immunity could result in more resources for plant growth. Indeed, these overexpression lines exhibited more susceptibility to pathogens in rice. This OsBON‐mediated growth phenotype might result from the hormone‐mediated trade‐off between defence and growth in rice (Deng et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2013, 2012). However, no significant changes in hormone levels were observed in the RNAi or overexpression lines of OsBON1 and OsBON3. Therefore, the data could support the inhibiting model where OsBON genes more directly inhibit immunity. Identifying the direct targets of copine proteins would ultimately differentiate these two models, and the two models may not be mutually exclusive. BON proteins might have different regulatory target proteins in different processes. A recent study of the Arabidopsis BON1 reveals its positive function at stomatal closure control, which could be explained by different target proteins of BON1 in different phases of plant immunity.

The rice OsBON1 knockdown and OsBON3 dominant negative lines display broad‐spectrum disease resistance to both bacterial and fungal pathogens. This is a very desirable trait in crop breeding, given that few genes have been molecularly characterized to be involved in such resistance. The identification of OsBON1/3 in broad‐spectrum resistance will not only enhance a mechanistic understanding of such resistance, but also provide a means to achieve such a resistance. Reduction of copine gene levels could be a potential way to generate resistance to bacterial and fungal pathogens not only in rice but also in other crops due to the likely conservation of copine genes in plants. Finding a right level of reduction of BON genes might achieve an enhancement of disease resistance without a substantial yield reduction.

Experimental procedures

Pathogen inoculation and disease resistance assay

For Xoo resistance assay, 2‐month‐old plants were inoculated with Philippine strain P6 (PXO99A) by the leaf‐clipping method as previously described (Yang et al., 2008). Bacteria were incubated on a peptone sucrose agar (PSA) medium at 28 °C for 3 days. Inoculum was prepared by suspending the bacterial mass in sterilized water at a concentration of OD600 = 1.0. Lesion length was measured and recorded 14 dpi. More than 50 leaves per genotype (five leaves per plant) were inoculated for statistical analysis. For bacterial growth curve, 20 cm of leaf tissue infected was ground in 10 mL sterile water to collect bacteria. Bacterial population was counted on PSA plates containing 15 mg/L cephalexin after 3 days of incubation at 28 °C. For Xoo induction of genes, plants were infected with Xoo strain PXO99A, and RNA was extracted from infected and water mock control leaves collected at different infection time points. Root inoculation was conducted as previously described (Chen et al., 2010).

For M. oryzae inoculation, virulent isolate Hoku1 was used. Rice seedlings at the three‐leaf stage in a chamber were sprayed with a conidial suspension (5 × 104 conidia/mL) with 0.02% Tween‐20 as described previously (Zou et al., 2016). Lesion size and number in the fourth leaf blades of each genotype were scored at 7 dpi with more than 10 leaves per genotype (one leaf per plant). The detailed progressiveness of invasive hyphal growth inside rice sheath cells was conducted and rated by types/stages I–IV as described previously (Kankanala et al., 2007). In brief, excised sheaths from 4‐week‐old rice seedlings were cut into 9‐cm strips and inoculated with conidial suspension of isolate Hoku1 (1 × 105 conidial/mL). Inoculated sheaths were incubated in a Petri dish containing wet filter paper such that the conidial suspension settled on the mid‐vein regions. The infectious hyphae in inner leaf sheath cells were observed at 38 hpi under a microscopy. Twenty samples from the inoculated sheaths (10 plants per genotype) were observed, and about 100 infecting hyphae were counted for each genotype.

For R. solani resistance assay, R. solani AG1‐IA isolate RH‐9 was used for inoculation with tooth picks as described by Wen et al. (Wen et al., 2015), with some modifications. In brief, sclerotia were transferred to a new PDA (potato dextrose agar) plate and grown for 2 days at 28°C. Short (0.8–1.0 cm) woody toothpicks were sterilized and co‐incubated with fungal plugs for 5 days at 28°C and then inserted into the third leaf sheath of rice plants grown in the paddy field at booting stage. Sheath blight symptom was recorded at 14 dpi with more than 20 sheaths per genotype (two sheaths per plant).

Other methods

Details of the methods for plant materials and growth conditions, plasmid construction, plant transformation, RNA isolation and gene expression analysis, antibody preparation, protein extraction and Western blotting, SA and JA measurements, histochemical analysis and protein subcellular localization are available in the supplementary methods (Appendix S1). All primers used for plasmid construction and gene expression analysis are listed in Table S1.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Expression pattern of OsBON1 and OsBON3.

Figure S2 OsBON1 negatively regulates disease resistance to Xoo strain PXO71 and PXO347.

Figure S3 OsBON1‐eGFP transgenic plants displayed enhanced disease susceptibility.

Figure S4 M. oryzae infection stage revealed by Uvitex 2B staining assay.

Figure S5 OsBON1 and OsBON3 do not complement Atbon1‐1 mutant phenotype.

Figure S6 OsBON1 does not affect SA and JA accumulation.

Figure S7 OsBON3 promotes rice growth and development.

Figure S8 Mutations in aspartate residues do not alter the subcellular localization of OsBON1 and OsBON3.

Figure S9 Subcellular localization change of OsBON3‐eGFP during Xoo infection.

Table S1 Primers used in this study.

Appendix S1 Supplementary methods.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Longjun Zeng and Jiyun Liu for rice growth and maintenance, Xin Wang for rice transformation assistance, Yiwen Deng for rice disease evaluation and Zhenguang Zhang, Hongsheng Zhang, Yongmei Bao and Muxing Liu for technical assistance of M. oryzae infection and microscopy. This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2016YFD0100601 and 2016ZX08009‐003‐001 to ZH), Natural Science Foundation of China (31330061 to ZH), Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA08010201 to ZH), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20150662 to BZ) and National Science Foundation of USA (IOS 1353738 to JH). The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Jian Hua, Email: jh299@cornell.edu.

Zuhua He, Email: zhhe@sibs.ac.cn.

References

- Agrawal, G.K. , Jwa, N.S. and Rakwal, R. (2000) A novel rice (Oryza sativa L.) acidic PR1 gene highly responsive to cut, phytohormones, and protein phosphatase inhibitors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 274, 157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, G.K. , Rakwal, R. and Jwa, N.S. (2001) Differential induction of three pathogenesis‐related genes, PR10, PR1b and PR5 by the ethylene generator ethephon under light and dark in rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings. J. Plant Physiol. 158, 133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F. , Gao, M.J. , Miao, Y.S. , Yuan, Y.X. , Wang, M.Y. , Li, Q. , Mao, B.Z. et al. (2010) Plasma membrane localization and potential endocytosis of constitutively expressed XA21 proteins in transgenic rice. Mol. Plant, 3, 917–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll, N.S. , Epple, P. and Dangl, J.L. (2011) Programmed cell death in the plant immune system. Cell Death Differ. 18, 1247–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creutz, C.E. , Tomsig, J.L. , Snyder, S.L. , Gautier, M.C. , Skouri, F. , Beisson, J. and Cohen, J. (1998) The copines, a novel class of C2 domain‐containing, calcium‐dependent, phospholipid‐binding proteins conserved from Paramecium to humans. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 1393–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl, J.L. and Jones, J.D. (2001) Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature, 411, 826–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vleesschauwer, D. , Gheysen, G. and Hofte, M. (2013) Hormone defense networking in rice: tales from a different world. Trends Plant Sci. 18, 555–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y. , Zhai, K. , Xie, Z. , Yang, D. , Zhu, X. , Liu, J. , Wang, X. et al. (2017) Epigenetic regulation of antagonistic receptors confers rice blast resistance with yield balance. Science, 355, 962–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou, M.Y. , Zhang, Z.M. , Zhang, N. , Huang, Q.S. , Monaghan, J. , Yang, H.J. , Shi, Z.Y. et al. (2015) Opposing effects on two phases of defense responses from concerted actions of HEAT SHOCK COGNATE70 and BONZAI1 in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 169, 2304–2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua, J. , Grisafi, P. , Cheng, S.H. and Fink, G.R. (2001) Plant growth homeostasis is controlled by the Arabidopsis BON1 and BAP1 genes. Genes Dev. 15, 2263–2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y. , Liu, G. , Park, D.S. and Yang, Y. (2013) Inoculation and scoring methods for rice sheath blight disease. Methods Mol. Biol. 956, 257–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.D. and Dangl, J.L. (2006) The plant immune system. Nature, 444, 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaku, H. , Nishizawa, Y. , Ishii‐Minami, N. , Akimoto‐Tomiyama, C. , Dohmae, N. , Takio, K. , Minami, E. et al. (2006) Plant cells recognize chitin fragments for defense signaling through a plasma membrane receptor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 11086–11091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kankanala, P. , Czymmek, K. and Valent, B. (2007) Roles for rice membrane dynamics and plasmodesmata during biotrophic invasion by the blast fungus. Plant Cell, 19, 706–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khang, C.H. , Berruyer, R. , Giraldo, M.C. , Kankanala, P. , Park, S.Y. , Czymmek, K. , Kang, S. et al. (2010) Translocation of Magnaporthe oryzae effectors into rice cells and their subsequent cell‐to‐cell movement. Plant Cell, 22, 1388–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. , Yang, S. , Yang, H. and Hua, J. (2007) The TIR‐NB‐LRR gene SNC1 is regulated at the transcript level by multiple factors. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 20, 1449–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. , Gou, M. , Sun, Q. and Hua, J. (2010) Requirement of calcium binding, myristoylation, and protein‐protein interaction for the Copine BON1 function in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 29884–29891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. , Yang, D.L. , Sun, L. , Li, Q. , Mao, B. and He, Z. (2016) The systemic acquired resistance regulator OsNPR1 attenuates growth by repressing auxin signaling through promoting IAA‐amido synthase expression. Plant Physiol. 172, 546–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W. , Liu, J. , Ning, Y. , Ding, B. , Wang, X. , Wang, Z. and Wang, G.L. (2013) Recent progress in understanding PAMP‐ and effector‐triggered immunity against the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae . Mol. Plant, 6, 605–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Loon, L.C. , Rep, M. and Pieterse, C.M.J. (2006) Significance of inducible defense‐related proteins in infected plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 44, 135–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melotto, M. , Underwood, W. , Koczan, J. , Nomura, K. and He, S.Y. (2006) Plant stomata function in innate immunity against bacterial invasion. Cell, 126, 969–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagano, M. , Ishikawa, T. , Fujiwara, M. , Fukao, Y. , Kawano, Y. , Kawai‐Yamada, M. and Shimamoto, K. (2016) Plasma membrane microdomains are essential for Rac1‐RbohB/H‐mediated immunity in rice. Plant Cell, 28, 1966–1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niño‐Liu, D.O. , Ronald, P.C. and Bogdanove, A.J. (2006) Xanthomonas oryzae pathovars: model pathogens of a model crop. Mol. Plant Pathol. 7, 303–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, D.‐S. , Sayler, R.J. , Hong, Y.‐G. , Nam, M.‐H. and Yang, Y. (2008) A method for inoculation and evaluation of rice sheath blight disease. Plant Dis. 92, 25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizo, J. and Sudhof, T.C. (1998) C2‐domains, structure and function of a universal Ca2 + ‐binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 15879–15882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robatzek, S. , Chinchilla, D. and Boller, T. (2006) Ligand‐induced endocytosis of the pattern recognition receptor FLS2 in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 20, 537–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, T. , Nakano, T. , Takamizawa, D. , Desaki, Y. , Ishii‐Minami, N. , Nishizawa, Y. , Minami, E. et al. (2010) Two LysM receptor molecules, CEBiP and OsCERK1, cooperatively regulate chitin elicitor signaling in rice. Plant J. 64, 204–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoel, S.H. and Dong, X. (2008) Making sense of hormone crosstalk during plant immune responses. Cell Host Microbe 3, 348–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, X. , Qi, J. , Zhu, X. , Mao, B. , Zeng, L. , Wang, B. , Li, Q. et al. (2012) The rice hydroperoxide lyase OsHPL3 functions in defense responses by modulating the oxylipin pathway. Plant J. 71, 763–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valent, B. and Chumley, F.G. (1991) Molecular genetic analysis of the rice blast fungus, Magnaporthe grisea . Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 29, 443–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valent, B. and Khang, C.H. (2010) Recent advances in rice blast effector research. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 13, 434–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdier, V. , Vera Cruz, C. and Leach, J.E. (2012) Controlling rice bacterial blight in Africa: Needs and prospects. J. Biotech. 159, 320–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.J. , Zhu, X.D. , Wang, L.Y. , Zhang, L.H. , Xue, Q.Z. and He, Z. (2005) Disease resistance and cytological analyses on lesion resembling disease mutant lrd40 in Oryza sativa . Chin. J. Rice Sci., 19, 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N. , Xiao, B. and Xiong, L. (2011) Identification of a cluster of PR4‐like genes involved in stress responses in rice. J. Plant Physiol. 168, 2212–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb, K.M. , Oña, I. , Bai, J. , Garrett, K.A. , Mew, T. , Vera Cruz, C.M. and Leach, J.E. (2010) A benefit of high temperature: increased effectiveness of a rice bacterial blight disease resistance gene. New Phytol. 185, 568–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.H. , Zeng, Y.X. , Ji, Z.J. and Yang, C.D. (2015) Mapping quantitative trait loci for sheath blight disease resistance in Yangdao 4 rice. Genet. Mol. Res. 14, 1636–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, C.A. and Hynes, R.O. (2002) Distribution and evolution of von Willebrand/integrin A domains: widely dispersed domains with roles in cell adhesion and elsewhere. Mol. Biol. Cell, 13, 3369–3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, R.A. and Talbot, N.J. (2009) Under pressure: investigating the biology of plant infection by Magnaporthe oryzae . Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 185–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S. and Hua, J. (2004) A haplotype‐specific resistance gene regulated by BONZAI1 mediates temperature‐dependent growth control in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell, 16, 1060–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S. , Yang, H. , Grisafi, P. , Sanchatjate, S. , Fink, G.R. , Sun, Q. and Hua, J. (2006) The BON/CPN gene family represses cell death and promotes cell growth in Arabidopsis. Plant J., 45, 166–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.L. , Li, Q. , Deng, Y.W. , Lou, Y.G. , Wang, M.Y. , Zhou, G.X. , Zhang, Y.Y. et al. (2008) Altered disease development in the eui mutants and Eui overexpressors indicates that gibberellins negatively regulate rice basal disease resistance. Mol. Plant, 1, 528–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.L. , Yao, J. , Mei, C.S. , Tong, X.H. , Zeng, L.J. , Li, Q. , Xiao, L.T. et al. (2012) Plant hormone jasmonate prioritizes defense over growth by interfering with gibberellin signaling cascade. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 109, 1192–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.L. , Yang, Y. and He, Z. (2013) Roles of plant hormones and their interplay in rice immunity. Mol. Plant, 6, 675–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You, Q. , Zhai, K. , Yang, D. , Yang, W. , Wu, J. , Liu, J. , Pan, W. et al. (2016) An E3 ubiquitin ligase‐BAG protein module controls plant innate immunity and broad‐spectrum disease resistance. Cell Host Microbe 20, 758–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y. , Zhong, S. , Li, Q. , Zhu, Z. , Lou, Y. , Wang, L. , Wang, J. et al. (2007) Functional analysis of rice NPR1‐like genes reveals that OsNPR1/NH1 is the rice orthologue conferring disease resistance with enhanced herbivore susceptibility. Plant Biotech. J. 5, 313–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. , Qian, W. and Hua, J. (2010) Temperature modulates plant defense responses through NB‐LRR proteins. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou, B. , Hong, X. , Ding, Y. , Wang, X. , Liu, H. and Hua, J. (2016) Identification and analysis of copine/BONZAI proteins among evolutionarily diverse plant species. Genome, 59, 565–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Expression pattern of OsBON1 and OsBON3.

Figure S2 OsBON1 negatively regulates disease resistance to Xoo strain PXO71 and PXO347.

Figure S3 OsBON1‐eGFP transgenic plants displayed enhanced disease susceptibility.

Figure S4 M. oryzae infection stage revealed by Uvitex 2B staining assay.

Figure S5 OsBON1 and OsBON3 do not complement Atbon1‐1 mutant phenotype.

Figure S6 OsBON1 does not affect SA and JA accumulation.

Figure S7 OsBON3 promotes rice growth and development.

Figure S8 Mutations in aspartate residues do not alter the subcellular localization of OsBON1 and OsBON3.

Figure S9 Subcellular localization change of OsBON3‐eGFP during Xoo infection.

Table S1 Primers used in this study.

Appendix S1 Supplementary methods.