Abstract

We previously reported that SSBXoc, a highly conserved single-stranded DNA-binding protein from Xanthomonas spp., was secreted through the type III secretion system (T3SS) and functioned as a harpin-like protein to elicit the hypersensitive response (HR) in the non-host plant, tobacco. In this study, we cloned SsbXoc gene from X. oryzae pv. oryzicola (Xoc), the causal agent of bacterial leaf streak in rice, and transferred it into Nicotiana benthamiana via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. The expression of SsbXoc in transgenic N. benthamiana enhanced growth of both seedling and adult plants. When inoculated with the harpin Hpa1 or the pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (Pst DC3000), the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) was increased more in SsbXoc transgenic lines than that in wild-type (WT) plants. The expression of pathogenesis-related protein genes (PR1a and SGT1), HR marker genes (HIN1 and HSR203J) and the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway gene, MPK3, was significantly higher in transgenic lines than in WT after inoculation with Pst DC3000. In addition, SsbXoc transgenic lines showed the enhanced resistance to the pathogenic bacteria P. s. tabaci and the improved tolerance to salt stress, accompanied by the elevated transcription levels of the defense- and stress-related genes. Taken together, these results indicate that overexpression of the SsbXoc gene in N. benthamiana significantly enhanced plant growth and increased tolerance to disease and salt stress via modulating the expression of the related genes, thus providing an alternative approach for development of plants with improved tolerance against biotic and abiotic stresses.

Keywords: transgenic N. benthamiana, SsbXoc, plant growth, hypersensitive response, pathogen resistance, stress tolerance

Introduction

Plants are exposed to diverse stress conditions throughout their life cycle, including biotic and abiotic stresses. To cope with biotic stress, plants employ innate immune systems to overcome the microbial invasion (Jones and Dangl, 2006; Thomma et al., 2011). The first line of defense is induced by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which includes a diverse group of molecules such as flagellin (Felix et al., 1999), EF-Tu (Kunze et al., 2004), chitin and harpins (He et al., 1993; Zou et al., 2006). Harpins are glycine-rich, heat-stable and protease-sensitive proteins that are secreted through the type III secretion system (T3SS) (Wei et al., 1992). Previous researches have demonstrated that plants are highly sensitive to harpin elicitors. The harpins stimulate the hypersensitive cell death, the oxidative burst and the expression of defense-related genes (He et al., 1993; Andi et al., 2001; Ichinose et al., 2001), and activate the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent signaling pathway (Desikan et al., 1999, 2001; Lee et al., 2001), which finally induce the defence response in plants.

Previous studies have shown that treatment with harpins induces plant growth (e.g., stimulates the elongation of roots) and enhances resistance to aphids in Arabidopsis (Dong et al., 2004; Lü et al., 2011, 2013). Up to now, multiple harpins have been expressed in plants, including Arabidopsis, rice, wheat, tobacco, cotton, and soybean, and the transgenic plants exhibited enhanced plant growth and improved resistance to pathogens (Jang et al., 2006; Shao et al., 2008; Miao et al., 2010; Choi et al., 2012; Wang D. et al., 2014; Du et al., 2018). For example, the transformation of cotton with hpa1 enhanced the defense response against Verticillium dahliae (Miao and Wang, 2013; Zhang et al., 2016). Furthermore, the heterologous expression of a functional fragment of the harpin protein Hpa1Xoo induced phloem-based defense against the English grain aphid in wheat (Fu et al., 2014). In addition, the expression of harpins also improves tolerance to abiotic stress. Previous studies demonstrate that HrpN increased drought tolerance by activating abscisic acid (ABA) signaling in Arabidopsis, and the harpin-encoding gene, hrf1, increased tolerance to drought stress in rice (Dong et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2011). Recent studies indicate that overexpression of the harpin-encoding gene, popW, enhances plant growth and resistance to R. solanacearum, and also increases drought tolerance in transgenic tobacco (Wang C. et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016). Increasing evidence shows that the multiple effects of harpins can be attributed to cross-talk of distinct signaling pathways to regulate development and defense in plants (Chen et al., 2008).

SSBs are highly conserved single-stranded DNA-binding proteins that protect ssDNA from nucleolytic digestion (Fedorov et al., 2006). We recently demonstrated that the SSB protein from Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola (Xoc) was shown to function as a harpin in tobacco (e.g., elicited an HR). Furthermore, treatment with SSBXoc improved plant growth and resistance to the fungal pathogen Alternaria alternate in Nicotiana tabacum cv. Xanthi (Li et al., 2013). In this study, the gene encoding Ssb in X. oryzae pv. oryzicola was transformed into N. benthamiana. Our research displays that SsbXoc transgenic plants exhibit enhanced plant growth, improved pathogen resistance, and increased tolerance to salt stress. To our knowledge, up to now there are no prior reports showing that the overexpression of harpins can enhance salt tolerance.

Materials and Methods

Generation of SsbXoc Transgenic N. benthamiana Plants

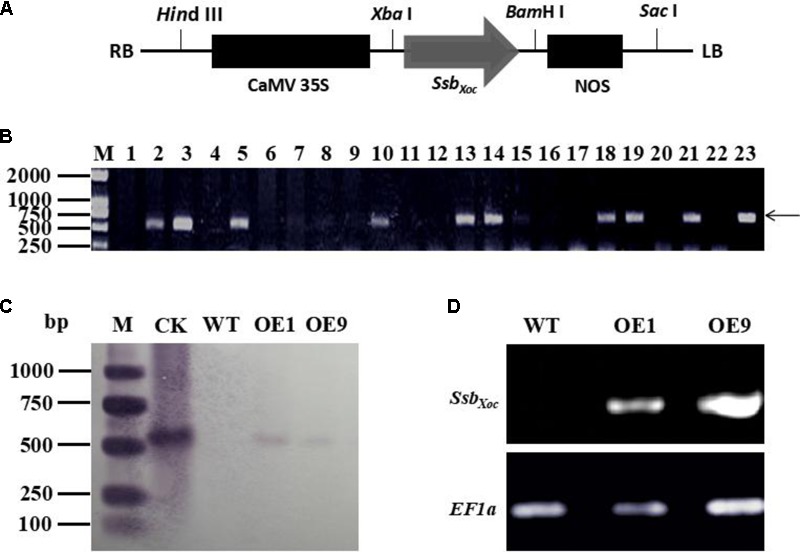

Full-length SsbXoc gene (552 bp) was amplified by PCR using the specific primers (Table 1). The amplified product was cloned into pMD18-T Simple Vector (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and then subcloned into the binary vector pCAMBIA2300 at XbaI and BamHI sites, which were placed downstream of the constitutive cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (CaMV35S) and upstream of the polyadenylation signal of the nopaline synthase terminator (NOS) (Figure 1A). The recombinant clone, pCAMBIA2300-SsbXoc, was then transferred into Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA105 for transformation of N. benthamiana. The SsbXoc transgenic plants were determined by PCR amplification with the specific primers of SsbXoc till T2 generation.

Table 1.

Primers designed and used for PCR.

| Genes | Primer sequences (5′ – 3′) |

Purpose | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | ||

| SsbXoc | CGGGATCCATGGCCCGCGGCATCAATAAAGT | CCTCTAGATCAGAACGGGATATCGTCGTCGGC | Cloning |

| SsbXoc | ATGGCCCGCGGCATCAATAAAGT | TCAGAACGGGATATCGTCGTCGGC | RT-PCR, Probe |

| EF1α | AGACCACCAAGTACTACTGCAC | CCACCAATCTTGTACACATCC | RT-PCR |

| SsbXoc | CAGGGTGATGGTGGATACGG | ATATCGTCGTCGGCGAAATC | qRT-PCR |

| PR1a | GGTGTAGAACCTTTGACCTGGG | AAATCGCCACTTCCCTCAGC | qRT-PCR |

| PR2 | TAGAGAATACCTACCCGCCC | GAGTGGAAGGTTATGTCGTGC | qRT-PCR |

| PR4 | GTGACGAACACAAGAACAGGAA | CCACTCCATTTGTGTCCAAT | qRT-PCR |

| SGT1 | CCTTCTATGAGCAGACATCCCA | GCGTCCAGTATGACAACCCA | qRT-PCR |

| HIN1 | TGCGTCCAGTATTCAAAGGTCA | GCTTCACTTCCATCTCATAAACCC | qRT-PCR |

| HSR203J | TGCGTCCAGTATTCAAAGGTCA | GCTTCACTTCCATCTCATAAACCC | qRT-PCR |

| MPK3 | CGGCACATGGAACACG | GACCGAATAATCTGATGAAGG | qRT-PCR |

| APX | TGGAACCCATCAAGGAGCAG | ATCAGGTCCTCCAGTGACTTC | qRT-PCR |

| GPX | GTTTCCGCTAAGAGATTTGAGTTG | CCCTTAGCATCCTTGACAGTG | qRT-PCR |

| CAT1 | AACAAGGCTGGGAAATCAACC | TGGCTGTGATTTGCTCCTCC | qRT-PCR |

| EXPA1 | TTGTTTCTCTGCTTCTGGATGG | CTTAATGCAGCAGTGTTTGTACCA | qRT-PCR |

| EIN2 | GGCATAATAGATCTGGCATTTTCC | TATCTAAGAGCATCGGTGCAGTTG | qRT-PCR |

| EF1α | AGACCACCAAGTACTACTGCAC | CCACCAATCTTGTACACATCC | qRT-PCR |

FIGURE 1.

Identification of SsbXoc transgenic N. benthamiana plants. (A) Construction of vector expressing SsbXoc in transgenic N. benthamiana. The CaMV promoter and nopaline synthase (NOS) polyadenylation signal are shown in black solid rectangles and flanked the SsbXoc coding region. (B) PCR analysis of transgenic lines using the SsbXoc-specific primers. Lane M, molecular weight marker; lanes 1-22 represent different transgenic lines, and lanes 2 and 21 are lines OE1 and OE9, respectively. Lane 23 contains the positive control, and the arrow shows the location of the 552-bp SsbXoc PCR product. (C) Southern blot hybridization of transgenic lines, OE1 and OE9, with dig-labeled SsbXoc. Lanes: M, molecular weight marker; CK, check, pCAMBRIA2300-SsbXoc; WT, wild-type N. benthamiana; OE1 and OE9, transgenic lines containing SsbXoc gene. (D) Expression measurement of SsbXoc gene in transgenic lines OE1 and OE9 by RT-PCR. The housekeeping gene, EF1α, was used as an internal control for normalizing the data.

Plants and Growth Conditions

Seeds of WT and SsbXoc transgenic lines OE-1 and OE-9 (T2 generations) were surface-sterilized with 75% ethanol and 10% sodium hypochlorite for 0.5 and 5 min, respectively. They were then separately transferred to Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium without or with 100 mg L-1 kanamycin and cultivated in a light-controlled incubator at 25°C. Fifteen days later, the seedlings were transplanted to pots and grown in a greenhouse with a 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod with 50% relative humidity at 25°C.

Plant Growth Analysis

The root lengths of transgenic lines (T2 generations) and WT plants grown in MS medium were measured after 15 days. Three independent experiments were performed and at least 20 seedlings were analyzed in each experiment. The phenotypes of plants were determined after the seedlings were transplanted to pots and cultivated for 4 weeks.

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

Bacterial strains used in this study were Pst DC3000 and P. s. tabaci. Both of them were grown at 28°C on King’s medium B (KMB) with or without rifampicin, respectively. They were resuspended and diluted to the appropriate concentration with 10 mM MgCl2 for subsequent research.

Determination of ROS Levels

Fully developed leaves of 2-month-old WT and T2 SsbXoc transgenic plants were separately injected with 100 μl Hpa1 protein (10 μg ml-1)and Pst DC3000 (OD600 = 0.01) using 1-mL needleless syringes. After 6 h, treated leaves were collected and incubated in diaminobenzidine (DAB) for 8 h at 25°C and then were immersed in boiling ethanol (95%) for 10 min to remove the dye (Thomas and Lemmer, 2005). After further incubation in 60% ethanol for 4 h, photographs were taken for visualization of reactive oxygen species (ROS). To quantify ROS accumulation, treated samples were collected separately at 0 and 6 hpi for detection of H2O2 contents as described previously (Bernt and Bergmeyer, 1974; Cao et al., 2015).

Bacterial Growth Analysis

The fully expanded leaves of 2-month-old WT and T2 SsbXoc transgenic lines were inoculated with P. s. tabaci (OD = 0.01), and the phenotypes were photographed at 36 hpi. In order to quantify the bacterial growth, the plants were inoculated with 105 CFU/ml P. s. tabaci as described previously (Klement, 1963; Thilmony et al., 1995). Briefly, a P. s. tabaci strain was grown overnight in KMB, washed twice, and resuspended at the appropriate concentration in 10 mM MgCl2. And bacterial suspensions were then infiltrated into fully developed leaves using 1-mL needleless syringes. To determine bacterial growth in plants, 1 cm2 leaf disks were excised from the inoculated tissue of each treatment at 0, 1, and 2 dpi. The bacterial populations in the leaves were determined by plating serial dilutions on KMB.

RNA Isolation and Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from leaves of WT and SsbXoc transgenic plants (T1 and T2 generation) using TRIzol reagent (TaKaRa, Japan) as recommended by the manufacturer. RT-PCR with gene-specific primer pairs was performed to evaluate the expression of SsbXoc in WT and transgenic plants. The expression of SsbXoc and genes related to the defense response, oxidative stress, and salt stress was measured using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), and all of the primers used in these experiences were listed in Table 1. EF1α was used as an internal standard in these experiments.

Southern Blot Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from WT and T1 SsbXoc transgenic lines using CTAB as described previously (Murray and Thompson, 1980). The recombinant plasmid pMD18-SsbXoc and genomic DNA were digested with BamHI and XbaI enzymes, and fragments were separated by electrophoresis in a 1.3% agarose gel at 80 V for 12 h. DNA was transferred to nylon membranes and hybridized with the SsbXoc PCR product, which was labeled with digoxigenin as recommended by the manufacturer (Dig-Labeling Kit, Roche). Conditions for hybridization and detection were followed as described by Aviv et al. (2011). The primers used for amplifying the SsbXoc probe were listed in Table 1.

Salt Stress Tolerance Assays

To examine germination rates during salt stress, seeds of T2 SsbXoc transgenic lines and WT plants were surface-sterilized and sown on MS medium supplemented with 100 mM NaCl cultivated in a light-controlled incubator with a 14-h light/10-h dark photoperiod at 25°C. Germination rates were assayed after 5 days. For analysis of chlorophyll content, leaf disks (1 cm diameter) were excised from fully expanded leaves and floated separately on solutions containing 0, 200, and 400 mM NaCl for 4 d in the incubator. Chlorophyll contents were measured as described by Porra (2002), Kanneganti and Gupta (2008). Leaves were sampled for the measurements of malondialdehyde (MDA) and proline using previously described methods (Bates et al., 1973; Cao et al., 2014) after treatment with salt for 4 days.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were repeated three times. Data were presented as the mean ± SD and analyzed using Excel and SPSS. Tukey’s test (P < 0.05) was used to determine significant differences.

Results

Generation of SsbXoc Transgenic N. benthamiana

To quickly determine whether SsbXoc gene was present in transformed N. benthamiana, potential transgenic plants (T0 generation) were initially screened by PCR using the SsbXoc-specific primers. Nine lines were obtained that existed a prominent 552-bp fragment in the genomic DNA, which was the predicted size of SsbXoc gene (Figure 1B). Two transgenic lines designated OE1 and OE9 were randomly selected for further characterization. Genomic DNA was extracted from OE1 and OE9 and analyzed by Southern blot hybridization. Both lines contained a 0.55-kb hybridizing fragment that corresponded with the predicted size of SsbXoc gene, and this signal was not detected in WT plants (Figure 1C). Thus, both PCR and Southern blot analyses indicated that SsbXoc gene had been incorporated into the genome of OE1 and OE9 transgenic plants. To determine whether SsbXoc was expressed in the transgenic lines, the accumulation of SsbXoc mRNA was evaluated by RT-PCR using EF1α as an internal standard. A 552-bp product was amplified from the transgenic lines OE1 and OE9, but not from WT (Figure 1D), indicating that SsbXoc gene was successfully expressed in transgenic lines. In addition, to quantify the expression level of SsbXoc gene in transgenic lines, the qRT-PCR experiment was performed using SsbXoc specific primers (Table 1). The result showed that the expression level of SsbXoc in OE9 line was higher than that in OE1 line (Supplementary Figure S1).

Expression of SsbXoc in Transgenic N. benthamiana Enhances Plant Growth

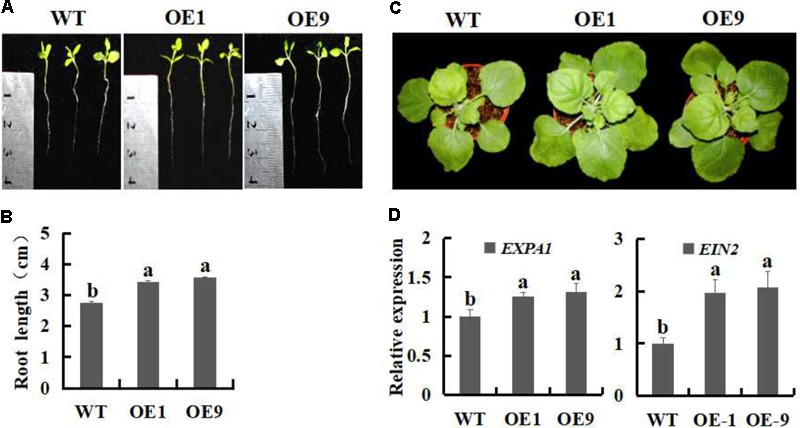

To evaluate whether the growth of SsbXoc transgenic plants was enhanced, root lengths were measured after cultivation in MS medium for 15 days. The transgenic lines OE1 and OE9 exhibited increased root lengths as compared with the WT (Figures 2A,B), and the difference was significant (P < 0.05). Four weeks after transplantation to pots, the transgenic lines still exhibited enhanced plant growth (Figure 2C). Previously, Goh et al. (2012) reported that genes in the expansin family, e.g., AtEXPA1, AtEXPA5 and AtEXPA10, were required for leaf growth, furthermore, the suppression of AtEXPA decreased foliar growth in Arabidopsis. EIN2 is demonstrate as an essential positive regulator in the ethylene signaling pathway, which is involved in many aspects of the plant life cycle (Johnson and Ecker, 1998; Wang et al., 2002). Thus, we measured the expression levels of expansin-encoding gene, EXPA1, and EIN2, to investigate whether the transcription of the two genes was enhanced in SsbXoc transgenic plants. As shown in Figure 2D, the transgenic lines exhibited higher expression of EXPA1 and EIN2 in comparison with WT, which further confirmed the enhanced growth evident in transgenic plants (Figure 2D).

FIGURE 2.

Growth phenotypes of WT and SsbXoc transgenic N. benthamiana plants. (A) Phenotypes of WT and transgenic lines incubation on MS medium for 15 days. (B) Root lengths on MS medium after 15 days. (C) Mature-stage phenotypes of plants after 6 weeks. (D) Expression analysis of EXPA1 and EIN2 by qRT-PCR in mature leaves of WT and transgenic N. benthamiana. plants. Error bars represent SD, and values with different letters are significantly different at P < 0.05.

SSBXoc Improves Defense Responses to Hpa1 and Pst DC3000 in Transgenic N. benthamiana

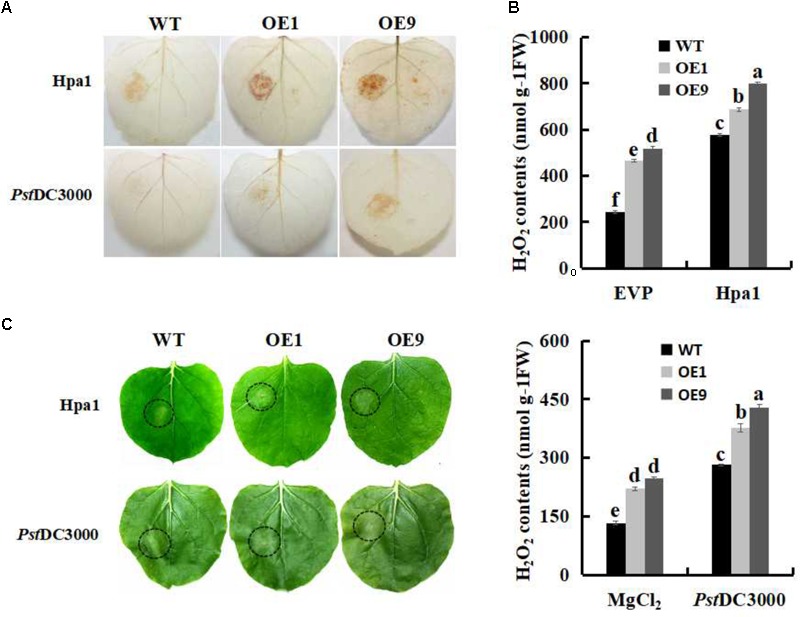

The Hpa1 protein and the pathogen of Pst DC3000 were individually inoculated to WT and SsbXoc transgenic plants to examine defense responses. DAB staining results indicated that ROS levels were significantly enhanced in SsbXoc transgenic lines as compared with WT (Figure 3A). H2O2 contents were then evaluated to quantify ROS levels in treated leaves. As shown in Figure 3B, transgenic lines exhibited higher levels of H2O2 accumulation than WT plants after inoculation with Hpa1 (Figure 3B, upper panel) and Pst DC3000 (Figure 3B, lower panel).

FIGURE 3.

The oxidative burst assay in WT and SsbXoc transgenic N. benthamiana plants inoculated with Hpa1 and Pst DC3000. WT and transgenic plants were injected with Hpa1 protein (10 μg ml-1) and Pst DC3000 pathogen (OD = 0.01), and at 6 hpi, treated leaves were collected. (A) Visualization of H2O2 accumulation by DAB staining in leaves inoculated with Hpa1 and Pst DC3000. (B) Evaluation of H2O2 levels in leaves. Upper panel shows H2O2 levels in WT and transgenic lines inoculated with empty vector preparation (EVP; negative control) and Hpa1; Lower panel shows H2O2 levels in WT and transgenic lines inoculated with 10 mM MgCl2 (negative control) and Pst DC3000. (C) Phenotypes of WT and transgenic lines inoculated with Hpa1 and Pst DC3000 after 24 h. Inoculation sites are indicated with open circles. Error bars represent SD, and values with different letters are significant at P < 0.05.

The accumulation of ROS in response to harpins and incompatible pathogens is generally accompanied by the HR (Zurbriggen et al., 2010). Therefore, WT and SsbXoc transgenic lines were evaluated visually for the HR at 24 hpi. The results showed that, after inoculated with Hpa1 and Pst DC3000 for 24 h, WT plants started to appear the HR, while transgenic lines reacted earlier and formed a more prominent HR at the inoculation site (Figure 3C), indicating that SsbXoc transgenic plants activated defense response earlier than WT, and this promoted the pathogen resistance.

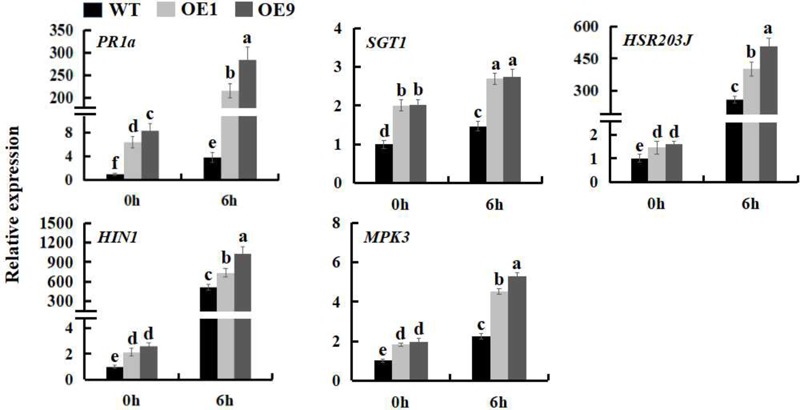

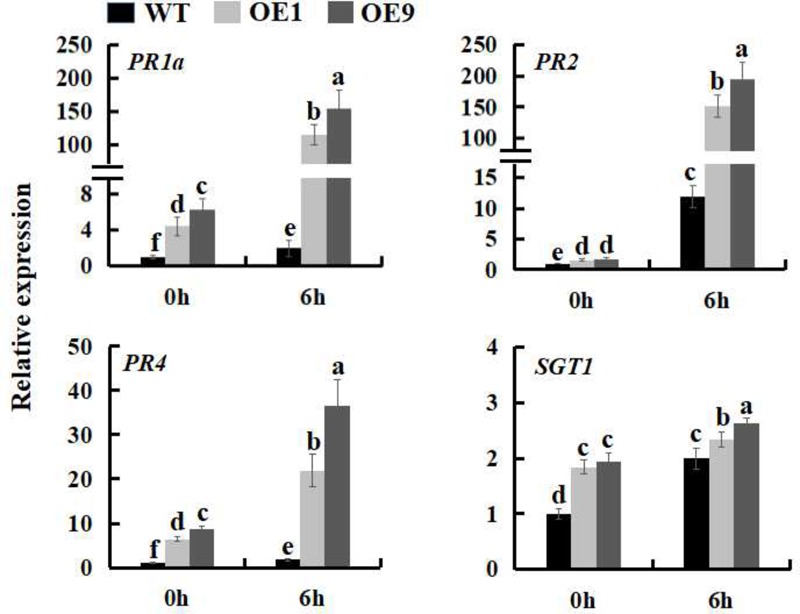

SSBXoc Enhances the Expression of Defense Related-Genes in Transgenic N. benthamiana

The expression of many defense genes can be activated during pathogen invasion in plants, including the pathogenesis-related (PR) genes, which play an important role in plant defense response (Maurhofer et al., 1994; Van Loon, 1997). To further investigate the mechanism underlying the increased pathogen resistance of SsbXoc transgenic plants, the expression levels of the PR genes, PR1a and SGT1, HR marker genes, HIN1 and HSR203J, and a gene involved in the MAPK-dependent signaling pathway, MPK3, were examined during infection by Pst DC3000. The results showed that at the time of inoculation with Pst DC3000 (0 hpi), the expression of defense-related genes was higher in transgenic lines as compared to WT; at 6 hpi, the expression levels of the five genes were all upregulated in all of the plants, while they were increased more in transgenic lines (Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure S2), further indicating that SsbXoc transgenic lines could respond more quickly to the invasion of Pst DC3000.

FIGURE 4.

Expression analysis of defense related-genes in WT and SsbXoc transgenic N. benthamiana plants inoculated with Pst DC3000. Two-month-old seedlings were inoculated with Pst DC3000 (OD = 0.01). At 0 and 6 hpi, the leaves were sampled to extract the total RNA to synthesize cDNA, and the transcription levels of PR1a, SGT1, HIN1, HSR203J and MPK3 genes were examined by qRT-PCR. Error bars represent SD, and values with different letters are significantly different at P < 0.05.

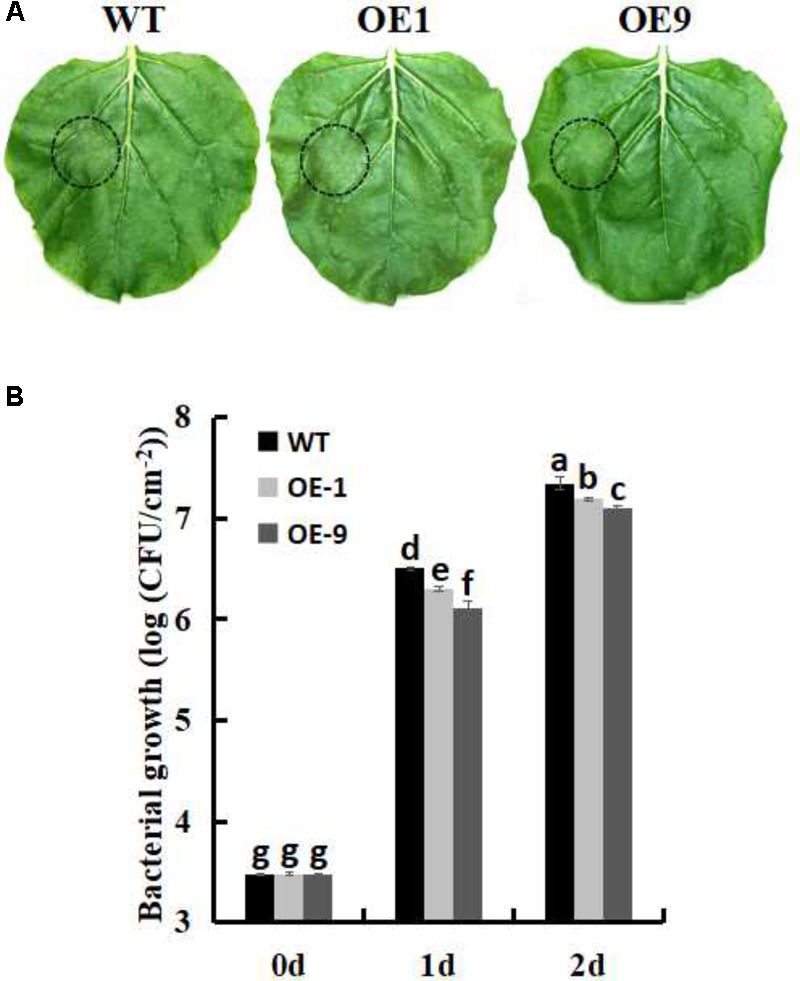

Overexpression of SsbXoc Improves Resistance to P. s. tabaci

In order to investigate whether SsbXoc transgenic plants could improve bacterial disease resistance, one pathogenic bacteria, P. s. tabaci, was used. As shown in Figure 5A, SsbXoc transgenic lines displayed less disease symptoms than WT plants at 36 h after inoculation with P. s. tabaci (Figure 5A). Correspondingly, the growth of P. s. tabaci was significantly lower in transgenic lines than that in WT plants at 1 and 2dpi, respectively (Figure 5B), being consistent with the necrosis symptoms in plants. In addition, the expression of defense genes was assayed in WT and SsbXoc transgenic plants after inoculation with P. s. tabaci. The results displayed that SsbXoc transgenic lines showed a higher expression of the pathogenesis-related genes, PR1a, PR2, PR4 and SGT1, than that of WT at the time of inoculation (0 hpi), and at 6 hpi, the expression levels of all the four genes were upregulated, however, they were more higher in transgenic lines than in WT (Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure S2). All of the above results indicated that SsbXoc transgenic plants had an improvement in resistance to the pathogenic bacterium, P. s. tabaci.

FIGURE 5.

Measurement of bacterial growth in WT and SsbXoc transgenic N. benthamiana plants inoculated with P. s. tabaci. (A) Phenotypic observation of the leaves in WT and transgenic lines after inoculation with P. s. tabaci (OD = 0.01) for 36 h (B) Bacterial growth in WT and transgenic lines was determined at 0, 1, and 2 days after inoculation with P. s. tabaci (105 CFU/ml). Error bars represent SD, and values with different letters are significantly different at P < 0.05.

FIGURE 6.

Expression analysis of defense genes in WT and SsbXoc transgenic N. benthamiana plants inoculated with P. s. tabaci. Two-month-old seedlings were inoculated with P. s. tabaci (OD = 0.01). At 0 and 6 hpi, the leaves were sampled to extract the total RNA to synthesize cDNA, and the expression levels of PR1a, PR2, PR4, and SGT1 genes were analyzed by qRT-PCR. Error bars represent SD, and values with different letters are significantly different at P < 0.05.

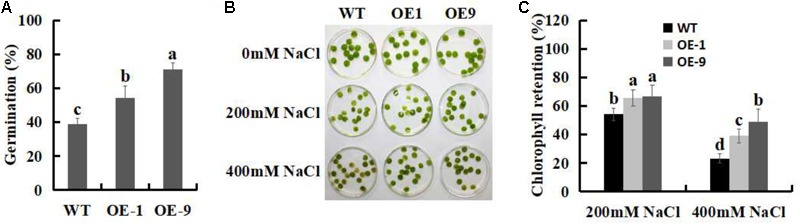

SSBXoc Enhances Seed Germination and Chlorophyll Retention During Salt Stress

The potential role of SSBXoc in improving salt stress tolerance was initially investigated by measuring the germination of the seeds after treatment with 100 mM NaCl. As shown in Figure 7A, the percentages of seed germination of the two SsbXoc transgenic lines were 54.5 and 71%, respectively, which were significantly higher than WT (38.8%). This result showed that the improved germination rate was most pronounced in OE9 transgenic line (Figure 7A).

FIGURE 7.

Effects of salt stress on seed germination and chlorophyll content in WT and SsbXoc transgenic N. benthamiana plants. (A) Analysis of percent seed germination after treatment with 100 mM NaCl for 5 d. (B) Phenotypic observation of chlorophyll retention in WT and transgenic leaf disks after treatment with 0, 200, and 400 mM NaCl for 4 d. (C) Chlorophyll contents in WT and transgenic plants after treatment with 200 and 400 mM NaCl for 4 d. Error bars represent SD, and values with different letters are significant at P < 0.05.

Chlorophyll retention is used as a physiological indicator of salt tolerance in plants (Sui et al., 2017). In the present study, a chlorophyll retention assay was performed to evaluate the salt tolerance in WT and SsbXoc transgenic plants when they were exposed to 0, 200, and 400 mM NaCl. The results showed that when exposed to 200 mM NaCl, the chlorophyll contents of WT, OE1 and OE9 were 54.3, 65.9, and 67%, respectively, and they were further reduced to 23.3, 39.1, 49% during treatment with 400 mM NaCl, respectively (Figures 7B,C). Thus, chlorophyll retention was higher in SsbXoc transgenic lines than in WT, suggesting that overexpression of SsbXoc improved salt tolerance in transgenic N. benthamiana.

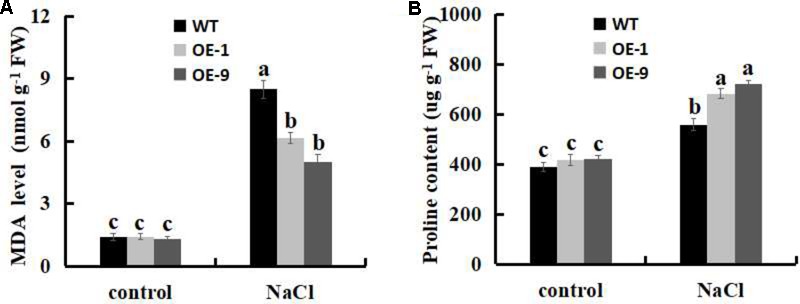

SSBXoc Decreases MDA Level and Increases Proline Content During Salt Stress

Malondialdehyde level has been used as a biological marker for the end-point of lipid peroxidation (Yoshimura et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2017), thus, we measured the MDA levels in WT and SsbXoc transgenic plants under the salt stress. No differences were observed in MDA contents between WT and SsbXoc transgenic lines when exposed to 0 mM NaCl, however, MDA level was significantly higher in WT than in transgenic lines after treatment with 200 mM NaCl (Figure 8A), indicating that lipid peroxidation, and hence membrane damage, was lower in transgenic N. benthamiana.

FIGURE 8.

Analysis of physiological indicators of lipid peroxidation (MDA) and proline in WT and SsbXoc transgenic N. benthamiana plants under salt stress. (A) MDA levels and (B) Proline contents in WT and transgenic plants after treatment with 0 and 200 mM NaCl for 4 d. Error bars represent SD, and values with different letters are significant at P < 0.05.

The accumulation of proline in plant cells is indicative of enhanced salt stress tolerance (Vinocur and Altman, 2005; Miller et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2015). Therefore, we evaluated the proline contents of leaves in WT and transgenic lines when they were exposed to salt stress. As shown in Figure 8B, no obvious differences were observed in proline contents between WT and SsbXoc transgenic lines without NaCl treatment, however, in transgenic lines, proline contents significantly increased more than in WT after treatment with 200 mM NaCl (Figure 8B). Thus, the increased proline contents implies the improved salt tolerance in SsbXoc transgenic plants.

SSBXoc Improves the Expression of Stress-Related Genes During Salt Stress

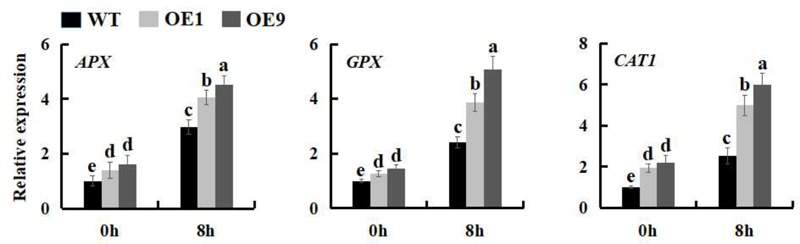

More and more results demonstrated that plants modulate the expression of many stress-related genes as an adaptation to environmental stress (Umezawa et al., 2006; Chinnusamy et al., 2007; Hirayama and Shinozaki, 2010; Bharti et al., 2016). To better understand the mechanistic basis of salt tolerance in SsbXoc transgenic lines, we measured the expression levels of three stress-related genes, APX, GPX and CAT1, which separately encode ascorbate peroxidase, glutathione peroxidase, and catalase. As shown in the Figure 9, SsbXoc transgenic plants displayed a higher basal expression level of the three genes as compared to WT without salt stress; under 200 mM NaCl treatment, the expression levels of these three genes were all significantly enhanced in WT and SsbXoc transgenic lines, while they were increased more in the latter (Figure 9). These results indicated that SsbXoc transgenic N. benthamiana plants improved salt tolerance through up-regulating the expression of stress-related genes.

FIGURE 9.

Expression levels of stress-related genes in WT and SsbXoc transgenic N. benthamiana plants under salt stress. Two-month-old seedlings were treated with 0 and 200 mM NaCl, and after 8 h, the leaves were sampled to extract the total RNA to synthesize cDNA. The expression levels of APX, GPX and CAT1 genes were analyzed by qRT-PCR. Error bars represent SD, and values with different letters are significant at P < 0.05.

Discussion

SSBXoc Improves Plant Growth in Transgenic N. benthamiana

We previously demonstrated that the exogenous application of SSBXoc enhanced growth of tobacco and Arabidopsis (Li et al., 2013). In this study, we cloned SsbXoc gene from X. oryzae pv. oryzicola and transferred it into N. benthamiana via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Two SsbXoc transgenic lines (OE1 and OE9) were characterized, and both of them showed improved root elongation and enhanced foliar growth as compared to WT plants (Figures 2A–C). Previous study reported that the expansin family genes were required for leaf growth (Goh et al., 2012) and EIN2 participated in the process of plant development and positively regulated the ethylene signaling pathway (Johnson and Ecker, 1998; Wang et al., 2002). Thus, we measured the expression levels of one expansin-encoding gene, EXPA1 and EIN2 to investigate whether or not they were changed in SsbXoc transgenic plants. As shown in Figure 2D, the transgenic lines exhibited higher expression of the two genes in comparison with WT, which further confirmed the growth phenotypes of SsbXoc transgenic plants (Figure 2C).

SSBXoc Transgenic Plants Exhibit Potentiated Defense Responses

Many studies have demonstrated that the activation of MAPK-dependent signaling cascades (Nakagami et al., 2005), ROS, and defense gene expression (Nürnberger, 1999; Gómez-Gómez and Boller, 2000) occurs in most plant-pathogen interactions, which leads to an improved defense resistance. During this process, the activities of defense enzymes are usually triggered initially in the plant-pathogen interactions (Ramamoorthy et al., 2002), and the speed of these defense responses is faster in incompatible interactions (Kombrink and Somssich, 1995). Corresponded to these conclusions, the expression of PR genes was increased more in WT and SsbXoc transgenic N. benthamiana when the tested plants were inoculated with Pst DC3000 rather than P. s. tabaci, excepting for the expression of SGT1 in WT plants.

Reactive oxygen species, e.g., H2O2 and O2-, are primarily produced at the site of attempted pathogen invasion in plant cells (Nanda et al., 2010; Jwa and Hwang, 2017) and are indicative of pathogen recognition and activation of plant defense responses (Lamb and Dixon, 1997; Torres, 2010). Up to now, more and more researches demonstrate that exogenous harpins, including Hpa1, induce ROS accumulation in tobacco and Arabidopsis cell cultures (Desikan et al., 1998; Andi et al., 2001; Samuel et al., 2005; Zou et al., 2006; Li et al., 2013; Choi et al., 2013). In the current study, the ROS level was higher in SsbXoc transgenic plants after inoculation with Hpa1 protein and the incompatible pathogen, Pst DC3000 (Figure 3B), which finally led to an earlier HR (Figure 3C). In addition, the expression of PR genes, HR marker genes, and MPK3 gene was also higher in transgenic lines than that in WT after inoculation with Pst DC3000 for 6 h (Figure 4). In a word, the higher levels of ROS and the improved expression of defense-related genes in SsbXoc transgenic plants were consistent with the rapid elicitation of the HR. Previous studies have shown that the HR generally appears within 24 h after inoculation with an incompatible pathogen or harpin (Wei et al., 1992; He et al., 1993). In this study, we inoculated N. benthamiana plants with reduced levels of Hpa1 (10 μg ml-1) and Pst DC3000 (OD600 = 0.01). Using this approach, we discovered that SsbXoc transgenic plants were more sensitive to the two eliciting agents accompanied with the increased expression of SsbXoc gene in transgenic plants, finally leading to producing a stronger HR at 24 hpi than WT plants (Figure 3C and Supplementary Figure S1).

Previously, Nicotiana tabacum cv. Xanthi plants infiltrated with SSBXoc displayed an improved resistance to the tobacco pathogen, Alternaria alternata (Li et al., 2013). In the current study, another pathogenic bacterium, P. s. tabaci, was used to inoculate WT and SsbXoc transgenic N. benthamiana plants. The results showed that SsbXoc transgenic lines had the higher basal transcription levels of PR1a, PR2, PR4, and SGT1 as compared to WT plants. After inoculation with P. s. tabaci for 6 h, expression of PR genes was significantly increased more in SsbXoc transgenic lines, and this was accompanied by a slight reduction in pathogen growth than WT plants (Figures 5, 6), suggesting the enhanced bacterial resistance in SsbXoc transgenic N. benthamiana.

SsbXoc Transgenic Plants Show Improved Salt Tolerance

Salt stress has many deleterious effects on plant growth and development, and inhibits seed germination, chlorophyll retention, root length, and fructification (Zhang et al., 2006; Sui et al., 2017; Liang et al., 2018). We initially used percent seed germination and chlorophyll retention to evaluate salt tolerance and discovered that SsbXoc transgenic N. benthamiana plants displayed higher levels of germination rates and chlorophyll contents when exposed to different concentrations of NaCl (Figure 7), indicating the enhanced salt tolerance of transgenic plants.

We next used MDA and proline as bioindicators to investigate the salt stress tolerance of SsbXoc transgenic N. benthamiana in the present study. MDA is the main product of membrane lipid peroxidation when plants are under salt stress (Liang et al., 2018), and MDA content has been used as a biological marker for the degree of membrane damage (Yoshimura et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2017). In our current study, we noted lower MDA levels in SsbXoc transgenic lines than in WT under salt stress condition (Figure 8A), suggesting that the degree of lipid peroxidation was lower in transgenic lines. Proline is an important osmotic adjustment compound in plant cells and plays a crucial role in protecting macromolecules and cellular membranes (Singh et al., 2000; Miller et al., 2010; Liang et al., 2018). The elevated accumulation of proline in plant cells is indicative of enhanced salt stress tolerance (Vinocur and Altman, 2005; Miller et al., 2010). In our research, we also observed a significant increase of proline contents in transgenic lines as compared to WT plants (Figure 8B), implying the enhanced salt tolerance in SsbXoc transgenic N. benthamiana.

During salt stress, the concentration of ROS increases to a potentially toxic level. To overcome H2O2-related cellular damage, organisms produce various antioxidant enzymes, including ascorbate peroxidase (APX), glutathione peroxidase (GPX), and catalase (CAT) (Ozyigit et al., 2016). The improved expression of APX, GPX, and CAT was correlated with the increased salt tolerance in both WT and transgenic plants (Mishra and Tanna, 2017). In the current study, the expression of APX, GPX and CAT1 was higher in SsbXoc transgenic lines than in WT both under normal and salt stress conditions, particularly in OE9 line, which had the higher expression level of SsbXoc gene (Figure 9 and Supplementary Figure S1). Thus, in addition to the elevated proline levels, the activities of ROS-scavenging enzymes were also increased in transgenic lines, finally leading to the enhanced tolerance to salt stress in SsbXoc transgenic plants.

However, little is known about the mechanisms how harpins and SSB protein trigger many similar beneficial effects on plants, though both harpins (including Hpa1) and SSB protein have some common features as mentioned elsewhere in this report. We hypothesize that, SSBXoc, like Hpa1, is translocated through the T3SS into plant cells, and possibly also perceived in plant apoplast, where it is recognized by unknown receptor(s) that recruit other proteins to activate downstream signal transduction cascades for HR induction, leading to expression of Eth-dependent genes for plant growth and SA- or JA-dependent genes for plant defense. Nevertheless, the discovery of harpin or SSB receptors in plants is the key to understand this point.

Conclusion

Our previous research displays that SSB from X. oryzae pv. oryzicola shares many features in common with the harpin Hpa1. Similar to Hpa1, SSBXoc is an acidic glycine-rich, heat-stable protein that lacks cysteine residues, which can also stimulate an HR in tobacco (Li et al., 2013). Thus, in many aspects, SSBXoc functions in a similar manner to harpins. The present studies have shown that SSB proteins in Escherichia coli are found to bind to ssDNA in a sequence-independent manner, and protect ssDNA from forming secondary structures and subsequent degradation by nucleases (Shereda et al., 2008; Bianco, 2017). Although SSBXoc clearly functions as a harpin, it may also have additional functions that are similar to SSB in E. coli. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that SSBXoc may impart increased resistance to ROS in transgenic plants via the protective roles, such as the increased repair ability of single-stranded breaks due to oxidative stress. In a word, regardless of the precision mechanisms in the current study, SSBXoc has the potentials in improving plant growth, imparting enhanced disease resistance and improving salt tolerance in N. benthamiana.

Author Contributions

YC and GC designed the experiments. YC performed most of the experiments and analyzed most of the data. MY detected the H2O2 contents and analyzed part of the data. WM provided some experimental methods. YS constructed the plasmid of pCAMBRIA2300-SsbXoc. GC and YC wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by the National Major Project for Developing New GM Crops (2016ZX08001-002) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31471742).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.00953/full#supplementary-material

References

- Andi S., Taguchi F., Toyoda K., Shiraishi T., Ichinose Y. (2001). Effect of methyl jasmonate on harpin-induced hypersensitive cell death, generation of hydrogen peroxide and expression of PAL mRNA in tobacco suspension-cultured BY-2 cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 42 446–449. 10.1093/pcp/pce056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviv A., Hunt S. C., Lin J., Cao X., Kimura M., Blackburn E. (2011). Impartial comparative analysis of measurement of leukocyte telomere length/DNA content by Southern blots and qPCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:e134. 10.1093/nar/gkr634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates L. S., Waldren R. P., Teare I. D. (1973). Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 39 205–207. 10.1016/j.dental.2010.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernt E., Bergmeyer H. U. (1974). “Inorganic peroxides,” in Methods of Enzymatic Analysis ed. Bergmeyer H. U. (New York, NY: Academic Press; ) 4.2246–2248. 10.1016/B978-0-12-091304-6.50090-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti N., Pandey S. S., Barnawal D., Patel V. K., Kalra A. (2016). Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria Dietzia natronolimnaea modulates the expression of stress responsive genes providing protection of wheat from salinity stress. Sci. Rep. 6:34768. 10.1038/srep34768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco P. R. (2017). The tale of SSB. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 127 111–118. 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y. Y., Yang M. T., Chen S. Y., Zhou Z. Q., Li X., Wang X. J., et al. (2015). Exogenous sucrose influences antioxidant enzyme activities and reduces lipid peroxidation in water-stressed cucumber leaves. Biol. Plant. 59 147–153. 10.1007/s10535-014-0469-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y. Y., Yang M. T., Li X., Zhou Z. Q., Wang X. J., Bai J. G. (2014). Exogenous sucrose increases chilling tolerance in cucumber seedlings by modulating antioxidant enzyme activity and regulating proline and soluble sugar contents. Sci. Hortic. 179 67–77. 10.1016/j.scienta.2014.09.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Qian J., Qu S., Long J., Yin Q., Zhang C., et al. (2008). Identification of specific fragments of HpaGXooc, a harpin protein from Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola, that induce disease resistance and enhanced growth in rice. Phytopathology 98 781–791. 10.1094/PHYTO-98-7-0781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnusamy V., Zhu J., Zhu J. K. (2007). Cold stress regulation of gene expression in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 12 444–451. 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi M. S., Heu S., Paek N. C., Koh H. J., Lee J. S., Oh C. S. (2012). Expression of hpa1 gene encoding a bacterial harpin protein in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae enhances disease resistance to both fungal and bacterial pathogens in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Pathol. J. 28 364–372. 10.5423/PPJ.OA.09.2012.0136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi M. S., Kim W., Lee C., Oh C. S. (2013). Harpins, multifunctional proteins secreted by gram-negative plant-pathogenic bacteria. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 26 1115–1122. 10.1094/MPMI-02-13-0050-CR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan R., Clarke A., Atherfold P., Hancock J. T., Neill S. J. (1999). Harpin induces mitogen-activated protein kinase activity during defence responses in Arabidopsis thaliana suspension cultures. Planta 210 97–103. 10.1007/s004250050658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan R., Hancock J. T., Ichimura K., Shinozaki K., Neill S. J. (2001). Harpin induces activation of the Arabidopsis mitogen-activated protein kinases AtMPK4 and AtMPK6. Plant Physiol. 126 1579–1587. 10.1104/pp.126.4.1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan R., Reynolds A., Hancock J. T., Neill S. J. (1998). Harpin and hydrogen peroxide both initiate programmed cell death but have differential effects on defence gene expression in Arabidopsis suspension cultures. Biochem. J. 330 115–120. 10.1042/bj3300115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H. P., Peng J., Bao Z., Meng X., Bonasera J. M., Chen G., et al. (2004). Downstream divergence of the ethylene signaling pathway for harpin-stimulated Arabidopsis growth and insect defense. Plant Physiol. 136 3628–3638. 10.1104/pp.104.048900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H. P., Yu H., Bao Z., Guo X., Peng J., Yao Z., et al. (2005). The ABI2-dependent abscisic acid signalling controls HrpN-induced drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Planta 221 313–327. 10.1007/s00425-004-1444-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Q., Yang X., Zhang J., Zhong X., Kim K. S., Yang J., et al. (2018). Over-expression of the Pseudomonas syringae harpin-encoding gene hrpZm confers enhanced tolerance to Phytophthora root and stem rot in transgenic soybean. Transgenic Res. 27 277–288. 10.1007/s11248-018-0071-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov R., Witte G., Urbanke C., Manstein D. J., Curth U. (2006). 3D structure of Thermus aquaticus single-stranded DNA–binding protein gives insight into the functioning of SSB proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 34 6708–6717. 10.1093/nar/gkl1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix G., Duran J. D., Volko S., Boller T. (1999). Plants have a sensitive perception system for the most conserved domain of bacterial flagellin. Plant J. 18 265–276. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00265.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu M., Xu M., Zhou T., Wang D., Tian S., Han L., et al. (2014). Transgenic expression of a functional fragment of harpin protein Hpa1 in wheat induces the phloem-based defence against English grain aphid. J. Exp. Bot. 65 1439–1453. 10.1093/jxb/ert488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh H. H., Sloan J., Dorca-Fornell C., Fleming A. (2012). Inducible repression of multiple expansin genes leads to growth suppression during leaf development. Plant Physiol. 159 1759–1770. 10.1104/pp.112.200881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Gómez L., Boller T. (2000). FLS2: an LRR receptor–like kinase involved in the perception of the bacterial elicitor flagellin in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cell 5 1003–1011. 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80265-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S. Y., Huang H. C., Collmer A. (1993). Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae harpinPss: a protein that is secreted via the Hrp pathway and elicits the hypersensitive response in plants. Cell 73 1255–1266. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90354-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama T., Shinozaki K. (2010). Research on plant abiotic stress responses in the post-genome era: past, present and future. Plant J. 61 1041–1052. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04124.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinose Y., Andi S., Doi R., Tanaka R., Taguchi F., Sasabe M., et al. (2001). Generation of hydrogen peroxide is not required for harpin-induced apoptotic cell death in tobacco BY-2 cell suspension culture. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 39 771–776. 10.1016/S0981-9428(01)01300-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y. S., Sohn S. I., Wang M. H. (2006). The hrpN gene of Erwinia amylovora stimulates tobacco growth and enhances resistance to Botrytis cinerea. Planta 223 449–456. 10.1007/s00425-005-0100-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P. R., Ecker J. R. (1998). The ethylene gas signal transduction pathway: a molecular perspective. Annu. Rev. Genet. 32 227–254. 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. D., Dangl J. L. (2006). The plant immune system. Nature 444 323–329. 10.1038/nature05286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jwa N.-S., Hwang B. K. (2017). Convergent evolution of pathogen effectors toward reactive oxygen species signaling networks in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1687. 10.3389/fpls.2017.01687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanneganti V., Gupta A. K. (2008). Overexpression of OsiSAP8, a member of stress associated protein (SAP) gene family of rice confers tolerance to salt, drought and cold stress in transgenic tobacco and rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 66 445–462. 10.1007/s11103-007-9284-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klement Z. (1963). Rapid detection of the pathogenicity of phytopathogenic pseudomonads. Nature 199 299–300. 10.1038/199299b0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kombrink E., Somssich I. E. (1995). Defense responses of plants to pathogens. Adv. Bot. Res. 21 1–34. 10.1016/S0065-2296(08)60007-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze G., Zipfel C., Robatzek S., Niehaus K., Boller T., Felix G. (2004). The N terminus of bacterial elongation factor Tu elicits innate immunity in Arabidopsis plants. Plant Cell 16 3496–3507. 10.1105/tpc.104.026765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb C., Dixon R. A. (1997). The oxidative burst in plant disease resistance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 48 251–275. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Klessig D. F., Nürnberger T. (2001). A harpin binding site in tobacco plasma membranes mediates activation of the pathogenesis-related gene HIN1 independent of extracellular calcium but dependent on mitogen-activated protein kinase activity. Plant Cell 13 1079–1093. 10.1105/tpc.13.5.1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. R., Ma W. X., Che Y. Z., Zou L. F., Zakria M., Zou H. S., et al. (2013). A highly-conserved single-stranded DNA-binding protein in Xanthomonas functions as a harpin-like protein to trigger plant immunity. PLoS One 8:e56240. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang W., Ma X., Wan P., Liu L. (2018). Plant salt-tolerance mechanism: a review. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 495 286–291. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.11.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Wang Y., Zhou X., Wang C., Wang C., Fu J., et al. (2016). Overexpression of a harpin-encoding gene popW from Ralstonia solanacearum primed antioxidant defenses with enhanced drought tolerance in tobacco plants. Plant Cell Rep. 35 1333–1344. 10.1007/s00299-016-1965-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lü B., Sun W., Zhang S., Zhang C., Qian J., Wang X., et al. (2011). HrpNEa-induced deterrent effect on phloem feeding of the green peach aphid Myzus persicae requires AtGSL5 and AtMYB44 genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biosci. 36 123–137. 10.1007/s12038-011-9016-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lü B. B., Li X. J., Sun W. W., Li L., Gao R., Zhu Q., et al. (2013). AtMYB44 regulates resistance to the green peach aphid and diamondback moth by activating EIN2-affected defences in Arabidopsis. Plant Biol. 15 841–850. 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2012.00675.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurhofer M., Hase C., Meuwly P., Metraux J. P., Defago G. (1994). Induction of systemic resistance of tobacco to tobacco necrosis virus by the root-colonizing Pseudomonas fluorescens strain CHA0: influence of the gacA gene and of pyoverdine production. Phytopathology 84 139–146. 10.1094/Phyto-84-139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miao W., Wang J. (2013). Genetic Transformation of Cotton with a Harpin-encoding Gene hpaXoo Confers an Enhanced Defense Response Against Verticillium dahliae Kleb. Transgenic Cotton. New York City, NY: Humana Press; 223–246. 10.1007/978-1-62703-212-4_19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao W., Wang X., Li M., Song C., Wang Y., Hu D., et al. (2010). Genetic transformation of cotton with a harpin-encoding gene hpaXoo confers an enhanced defense response against different pathogens through a priming mechanism. BMC Plant Biol. 10:67. 10.1186/1471-2229-10-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G. A. D., Suzuki N., Ciftci-Yilmaz S., Mittler R. O. N. (2010). Reactive oxygen species homeostasis and signalling during drought and salinity stresses. Plant Cell Environ. 33 453–467. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A., Tanna B. (2017). Halophytes: potential resources for salt stress tolerance genes and promoters. Front. Plant Sci. 8:829. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray M. G., Thompson W. F. (1980). Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 8 4321–4326. 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagami H., Pitzschke A., Hirt H. (2005). Emerging MAP kinase pathways in plant stress signalling. Trends Plant Sci. 10 339–346. 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanda A. K., Andrio E., Marino D., Pauly N., Dunand C. (2010). Reactive oxygen species during plant-microorganism early interactions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 52 195–204. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00933.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nürnberger T. (1999). Signal perception in plant pathogen defense. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 55 167–182. 10.1007/s000180050283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozyigit I. I., Filiz E., Vatansever R., Kurtoglu K. Y., Koc I., Öztürk M. X., et al. (2016). Identification and comparative analysis of H2O2-scavenging enzymes (ascorbate peroxidase and glutathione peroxidase) in selected plants employing bioinformatics approaches. Front. Plant Sci. 7:301. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porra R. J. (2002). The chequered history of the development and use of simultaneous equations for the accurate determination of chlorophylls a and b. Photosynth. Res. 73 149–156. 10.1023/A:1020470224740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamoorthy V., Raguchander T., Samiyappan R. (2002). Induction of defense-related proteins in tomato roots treated with Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf1 and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici. Plant Soil 239 55–68. 10.1023/A:1014904815352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel M. A., Hall H., Krzymowska M., Drzewiecka K., Hennig J., Ellis B. E. (2005). SIPK signaling controls multiple components of harpin-induced cell death in tobacco. Plant J. 42 406–416. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02382.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao M., Wang J., Dean R. A., Lin Y., Gao X., Hu S. (2008). Expression of a harpin-encoding gene in rice confers durable nonspecific resistance to Magnaporthe grisea. Plant Biotechnol. J. 6 73–81. 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2007.00304.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shereda R. D., Kozlov A. G., Lohman T. M., Cox M. M., Keck J. L. (2008). SSB as an organizer/mobilizer of genome maintenance complexes. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43 289–318. 10.1080/10409230802341296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. K., Sharma H. C., Goswami A. M., Datta S. P., Singh S. P. (2000). In vitro growth and leaf composition of grapevine cultivars as affected by sodium chloride. Biol. Plant. 43 283–286. 10.1023/A:1002720714781 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sui N., Tian S., Wang W., Wang M., Fan H. (2017). Overexpression of glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase from Suaeda salsa improves salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1337. 10.3389/fpls.2017.01337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thilmony R. L., Chen Z., Bressan R. A., Martin G. B. (1995). Expression of the tomato Pto Gene in tobacco enhances resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv tabaci expressing AvrPto. Plant Cell 7 1529–1536. 10.1105/tpc.7.10.1529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M. A., Lemmer B. (2005). HistoGreen: a new alternative to 3, 3’-diaminobenzidine-tetrahydrochloride-dihydrate (DAB) as a peroxidase substrate in immunohistochemistry? Brain Res. Protoc. 14 107–118. 10.1016/j.brainresprot.2004.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomma B. P., Nürnberger T., Joosten M. H. (2011). Of PAMPs and effectors: the blurred PTI-ETI dichotomy. Plant Cell 23 4–15. 10.1105/tpc.110.082602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres M. A. (2010). ROS in biotic interactions. Physiol. Plant. 138 414–429. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01326.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezawa T., Fujita M., Fujita Y., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. (2006). Engineering drought tolerance in plants: discovering and tailoring genes to unlock the future. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 17 113–122. 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loon L. C. (1997). Induced resistance in plants and the role of pathogenesis-related proteins. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 103 753–765. 10.1023/A:1008638109140 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vinocur B., Altman A. (2005). Recent advances in engineering plant tolerance to abiotic stress: achievements and limitations. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 16 123–132. 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Liu H., Cao J., Guo J. (2014). Construction of transgenic tobacco expressing popW and analysis of its biological phenotype. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao 30 569–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Wang C., Li H. W., Wei T., Wang Y. P., Liu H. X. (2016). Overexpression of a harpin-encoding gene popW in tobacco enhances resistance against Ralstonia solanacearum. Biol. Plant. 60 181–189. 10.1007/s10535-015-0571-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Wang Y., Fu M., Mu S., Han B., Ji H., et al. (2014). Transgenic expression of the functional fragment Hpa110-42 of the harpin protein Hpa1 imparts enhanced resistance to powdery mildew in wheat. Plant Dis. 98 448–455. 10.1094/PDIS-07-13-0687-RE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Tang X., Wang H., Shao H. B. (2015). Proline accumulation and metabolism-related genes expression profiles in Kosteletzkya virginica seedlings under salt stress. Front. Plant Sci. 6:792. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Wu Y. H., Tian X. Q., Bai Z. Y., Liang Q. Y., Liu Q. L., et al. (2017). Overexpression of DgWRKY4 enhances salt tolerance in Chrysanthemum seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1592. 10.3389/fpls.2017.01592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K. L. C., Li H., Ecker J. R. (2002). Ethylene biosynthesis and signaling networks. Plant Cell 14(Suppl. 1) S131–S151. 10.1105/tpc.001768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z. M., Laby R. J., Zumoff C. H., Bauer D. W., He S. Y., Collmer H., et al. (1992). Harpin, elicitor of the hypersensitive response produced by the plant pathogen Erwinia amylovora. Science 257 85–88. 10.1126/science.1621099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura K., Miyao K., Gaber A., Takeda T., Kanaboshi H., Miyasaka H., et al. (2004). Enhancement of stress tolerance in transgenic tobacco plants overexpressing Chlamydomonas glutathione peroxidase in chloroplasts or cytosol. Plant J. 37 21–33. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01930.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Xiao S., Li W., Feng W., Li J., Wu Z., et al. (2011). Overexpression of a Harpin-encoding gene hrf1 in rice enhances drought tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 62 4229–4238. 10.1093/jxb/err131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R. H., Guo S. R., Li J. (2006). Effects of salt stress on root activity and chlorophyll content of cucumber. J. Chang Jiang Veget. 2 47–49. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Zhao J., Ding L., Zou L., Li Y., Chen G., et al. (2016). Constitutive expression of a novel antimicrobial protein, Hcm1, confers resistance to both Verticillium and Fusarium wilts in cotton. Sci. Rep. 6:20773. 10.1038/srep20773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L. F., Wang X. P., Xiang Y., Zhang B., Li Y. R., Xiao Y. L., et al. (2006). Elucidation of the hrp clusters of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola that control the hypersensitive response in nonhost tobacco and pathogenicity in susceptible host rice. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 6212–6224. 10.1128/AEM.00511-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurbriggen M. D., Carrillo N., Hajirezaei M. R. (2010). ROS signaling in the hypersensitive response: when, where and what for? Plant Signal. Behav. 5 393–396. 10.4161/psb.5.4.10793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.