Abstract

BACKGROUND: Androgen receptor (AR) has emerged as a significant prognostic marker in early breast cancer (BCa). Association of AR with cancer stem cell (CSC) markers in BCa is unknown. Aim of the present study was to evaluate the immunohistochemical expression of AR, CD44, CD24 and ALDH1 in a cohort of Pakistani patients diagnosed with invasive BCa and to correlate the expression with 5- year disease free survival. PATIENTS AND METHODS: We evaluated immunohistochemical expression AR, CD44, CD24 and ALDH1 in formalin fixed paraffin embedded archival blocks of 166 cases of primary invasive BCa (stage I-III) and correlated the expression with clinicopathological variables and outcome using univariable and multivariable analysis. Survival data was computed by Kaplan Meier curves. RESULTS: Expression of AR was observed in 62.7% tumors whereas CD44, CD24 and ALDH1 were expressed in 61.4%, 44% and 30.1% tumors, respectively. AR expression was significantly associated with T1-T2 tumors, lower grade, estrogen and progesterone receptor expression (P < .05) and remained an independent prognostic indicator in multivariable analysis (adjusted HR 0.33, 95% CI 0.13–0.81; P = .016). Significant association was observed between concordant expression of AR and CD24 (P = .001) with a favorable impact on survival (P = .007) whereas expression of CSC phenotypes (CD44+, CD44+/CD24− and ALDH1+) did not correlate with adverse outcome (P > .05). However, AR expression retained the association with better prognosis even in patients whose tumors exhibited a CSC phenotype. CONCLUSIONS: Expression of AR and CD24 in stage I-III invasive BCa correlates with favorable clinicopathological features and delineates a subgroup of patients with better disease-free survival.

Introduction

Androgen receptor (AR) is a ligand dependent transcription factor variably expressed in 60–77% of early invasive breast cancers (BCa) [1], [2], [3], [4]. Expression of AR in BCa is associated with molecular subtypes with highest expression observed in ER+ tumors (78.4%) where AR positivity has emerged as an independent prognostic marker associated with favorable clinicopathological features, predictor of response to chemotherapeutic and endocrine agents and better survival [2], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. These findings are in concordance with in vitro studies demonstrating that AR signaling exerts an anti-estrogenic effect by inhibiting ER mediated transcription of genes in luminal BCa cell lines [10]. However, the interplay between AR and ER is complex as it is also influenced by levels of AR and ER in the tumor, whereby AR to ER ratio of >2 selects for a subtype of ER+/AR+ tumors with an adverse outcome [11], [12].

Androgen receptor expression is also observed in 12–40% of triple negative breast cancers (TNBC) [13]. Considering the paucity of targeted treatments, AR has evolved as a promising therapeutic target in at least a subset of TNBC. This is well supported by in vitro studies where targeting AR with anti-androgens yielded anti-proliferative effect in a panel of TNBC cell lines [14]. However, the clinical significance of AR expression in predicting outcome of patients with TNBC remains ambiguous [13], [15], [16], [17].

There is consensus that cancers evolve from a cancer stem cells (CSCs) also referred to as the tumor initiating cells (TICs) [18]. CSCs in solid tumors were first identified in human BCa by Al-Hajj and colleagues who demonstrated that as few as 100 cells with CD44+/CD24−/low/Lin− phenotype, isolated from primary or metastatic sites can establish tumors and when serially passaged, transplantable in nude mice [19]. Ginestier and colleagues identified an ALDH1+ population of cells in normal and malignant human breast epithelium. They showed that high expressing ALDH1+ cells derived from BCa could be grown in vivo and xenotransplanted in an animal model [20]. The defining characteristics of CSC include self-renewal, clonal tumor initiation with a repopulating potential, phenotypic plasticity and metastasis.

In addition, in vivo and in vitro studies have shown that CSCs are quiescent, therapy resistant cells within the primary tumor and metastatic sites. Disease recurrences are hence attributed to arise from failure to eradicate the CSC population [18], [21]. However, the clinical significance of CSC phenotypes (CD44+/CD24− and ALDH1+) in BCa requires further investigation [22], [23], [24], [25].

In vivo and in vitro studies investigating the biological interaction between AR and ALDH1 in BCa are lacking and only limited studies have addressed the mechanisms underpinning the regulation of CSC phenotypes (CD44+/CD24−) by AR and AR signaling with conflicting results [26], [27], [28].

In view of these equivocal findings, it is important to determine if there is any association and prognostic relevance of AR in relation to CSC phenotypes. Hence, the aim of our study was to evaluate the immunohistochemical expression of AR, CD44, CD24 and ALDH1 in a cohort of Pakistani patients diagnosed with stage I-III invasive BCa and to correlate the expression with clinicopathological features and survival.

Patients and Methods

Study Design

Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH), Karachi, is one of the principal, not for profit teaching institutions in Pakistan. It is a 710-bed tertiary care center that receives referrals from across the country. Retrospective cohort study was undertaken and included adult female patients diagnosed with stage I-III invasive BCa from 2006–2010. Cases were identified from prospectively maintained BCa registry and included patients who had completed their management at AKUH. Total of 930 patients were registered in the defined study period, from which 166 cases were selected on basis of the following criteria; 1) availability of formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) archival blocks, 2) representative tumor tissue on hematoxylin and eosin stained sections, and 3) follow up clinical data.

Medical records were reviewed, and data was collected on structured questionnaire for clinico-pathological characteristics including age, menopausal status, TNM staging, surgical interventions and systemic therapies administered. In addition, data for histological details including tumor type, size, grade, ER/PR, and HER-2/neu expression and FISH analysis for HER-2/neu gene amplification was collected. Follow-up details and outcome comprising of loco-regional recurrences and death were recorded. Study protocol was approved by ethical review committee of Aga Khan University, Pakistan campus (2517-Pat-ERC-13). All patients had consented for their data and tumor tissues to be used for research. The study was planned incorporating the REMARK guidelines [29].

Immunohistochemical Expression

FFPE archival tissue blocks were retrieved from department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, AKUH. Appropriate blocks were selected by the pathologist, based upon representative tumor morphology on hematoxylin and eosin stained sections. Serial sections of 5um were cut onto poly-L-lysine coated glass slides (Dako-K8020).

For CD44, CD24 and ALDH1, sections were de-waxed in an oven (Memmert, UK) at 70°C for 40 minutes followed by de-paraffinization and gradual hydration in graded alcohol. Details of antibodies, appropriate controls, method of antigen retrieval, dilutions, incubation time and detection method are enlisted in online Supplementary Table S1.

Immunohistochemical Scoring

CD44 & CD24

Scoring for membranous and cytoplasmic expression of CD44 and CD24, respectively, was performed according to previously published criteria as follows: No expression (0); 1–10% positive tumor cells (1); 11–50% positive tumor cells (2); 51–75% positive tumor cells (3); 76–100% positive tumor cells (4) [30].

ALDH1

ALDH1 scoring was performed as described previously [31]. Briefly, percentage and intensity of cytoplasmic expression was recorded. Staining intensity was scored as 0 (no expression), 1 (weak expression), 2 (moderate expression) and 3 (strong expression). Product of percentage and intensity generated a numerical score (S = P x I). For statistical analysis, scores = 0 were considered as negative and positive expression was considered for all cases with scores >0.

AR

Nuclear expression of AR was scored in accordance with previously published Allred criterion [32]. Briefly, percentage of AR expressing cells was visually estimated. Allred score was calculated by taking into consideration the proportion (P) scored as 0–5 and intensity (I) scored as 1–3. Proportion and intensity were then summed up to generate a score from 0 through 8. Score of ≥3 was considered to be positive.

Acquisition of Images

The slides were imaged on virtual scanning microscope (VS-120: Olympus) at 20X and the images were acquired through Olympus OlyVIA software.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20 software. Descriptive statistics were computed for continuous (mean ± SD) and categorical variables. Duration of follow-up was recorded from date of diagnosis until death or until the date of last hospital visit at the time of data collection. Loco-regional relapses and deaths were expressed as frequencies. Association between expression of AR, CSC markers and clinico-pathological features was assessed by chi-square test or Fisher exact test, where appropriate and P-value of <0.05 was considered to be significant. Univariate analysis was performed by using cox proportional hazard model and results were reported as crude hazard ratio. All variables found to have a P-value of <0.2 were considered eligible for multivariable analysis and adjusted hazard ratio with 95% confidence intervals were reported using multiple cox proportional hazard model. Event was defined as death attributed to BCa.

5-year disease free survival (DFS) was measured from date of diagnosis until death due to BCa. Survival curves were acquired by using Kaplan Meir methodology and significance between different categories was determined by log rank analysis.

Results

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

Clinico-pathological characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1. The median age at diagnosis was 54 years (range: 28–87 years). Majority of tumors were invasive ductal (90.4%) followed by invasive lobular (3%) and remaining (6.6%) tumors belonged to mucinous, papillary, metaplastic and tubulo-lobular subtypes. More than half of patients (56.6%) were diagnosed with stage II. Positive expression of ER, PR was found in 60.2% and 52.4% of tumors respectively whereas HER-2/neu over-expression or amplification was present in 30% of primary tumors. Amongst 166 cases, 46.4% were luminal A (ER+ and/or PR+, HER-2/neu−), 13.9% were luminal B (ER+ and/or PR+, HER-2/neu+) and 16.3% tumors were HER-2/neu subtype and 23.5% were TNBC (ER−, PR−, HER-2/neu−) subtype. Mastectomy was performed in 72.2% patients while breast conservation was performed in 25% of cases. Systemic therapy was administered in adjuvant and neo-adjuvant setting in 60.8% and 21.1% of the patients, respectively. Systemic therapy comprised of adriamycin and taxane based chemotherapy in neo-adjuvant and adjuvant setting in all patients with the exception of three patients who were administered CMF (cyclophosphamide, Methotrexate and 5-Flourouracil) in adjuvant setting. Endocrine therapy was recommended where hormonal receptors were expressed and radiation therapy was recommended in accordance with NCCN® (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) guidelines. Mean duration of follow-up was 4.6 years (SD± 2.7 years) and 42 deaths, attributed to BCa were recorded in the entire cohort.

Table 1.

Clinical and Histopathological Characteristics of the Patients (n = 166)

| Features | n = 166 (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | Median: 54 (Range:28–87) |

| <40 | 20 (12) |

| 40–49 | 45 (27.1) |

| 50–59 | 38 (22.9) |

| 60–64 | 24 (14.5) |

| >65 | 39 (23.5) |

| Tumor Grade | |

| I | 15 (9) |

| II | 97 (58.4) |

| III | 54 (32.5) |

| Tumor Size (cm) | |

| T1 | 20 (12) |

| T2 | 86 (51.8) |

| T3 | 37 (22.3) |

| T4 | 23 (13.9) |

| Axillary Lymph Node Status | |

| N0 | 89 (53.6) |

| N1 | 43 (25.9) |

| N2 | 17 (10.2) |

| N3 | 17 (10.2) |

| TNM Stage | |

| I | 27 (16.3) |

| II | 94 (56.6) |

| III | 45 (27.1) |

| Estrogen Receptor Expression | |

| Positive | 100(60.2) |

| Negative | 66 (39.8) |

| Progesterone Receptor Expression | |

| Positive | 87 (52.4) |

| Negative | 79 (47.6) |

| HER-2/neu Expression | |

| Positive | 50 (30.1) |

| Negative | 116 (69.9) |

| Androgen Receptor Expression | |

| Positive | 104 (62.7) |

| Negative | 62 (37.3) |

| CD44 Expression | |

| Positive | 102 (61.4) |

| Negative | 64 (38.6) |

| CD24 Expression | |

| Positive | 73 (44) |

| Negative | 93 (56) |

| ALDH1 Expression | |

| Positive | 50 (30.1) |

| Negative | 116 (69.9) |

Immunohistochemical Expression of AR, CD24, CD44 and ALDH1

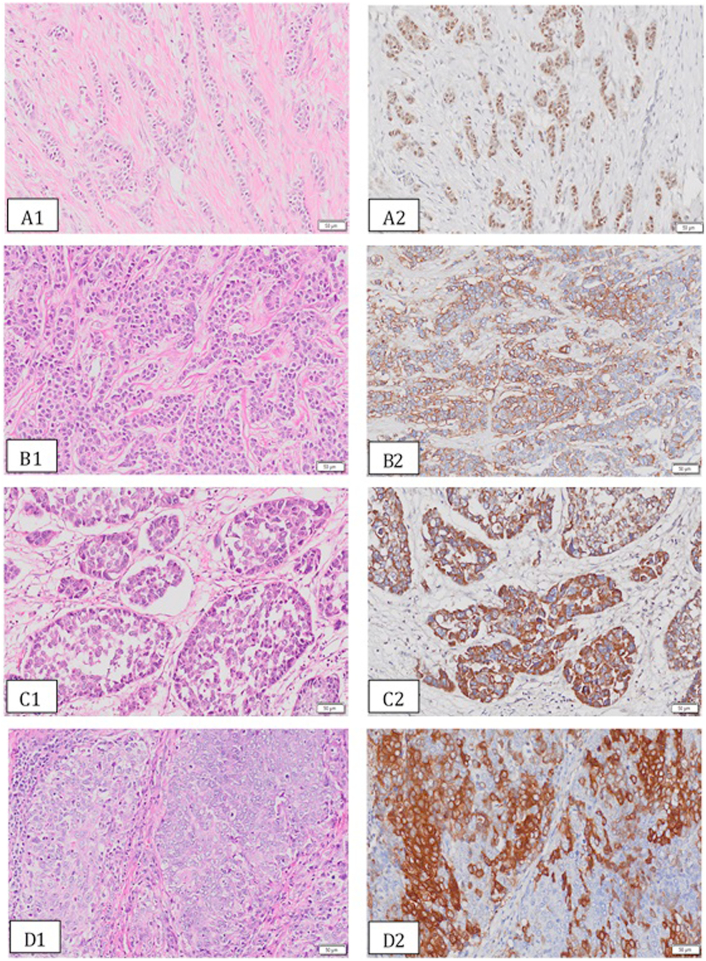

Overall, immunohistochemical expression of AR, CD44, CD24 and ALDH1 was observed in 62.7%, 61.4%, 44%, and 30.1% of tumors, respectively (Table 1). Immunostaining of CD24 and ALDH1 was predominantly cytoplasmic; whereas AR expression was localized to nucleus and CD44 was found to have membranous expression. Representative photomicrographs for expression of AR, CD44, CD24 and ALDH1 along with representative hematoxylin and eosin stained sections are presented in Figure 1 (A-D).

Figure 1.

(A-D): Representative photomicrographs for expression AR (A2), CD44 (B2), CD24 (C2) and ALDH1 (D2) in invasive BCa along with corresponding hematoxylin and eosin stained sections (A1-D1).

Association of Stem Cell Markers with Clinicopathological Features and Survival

CD44 expression

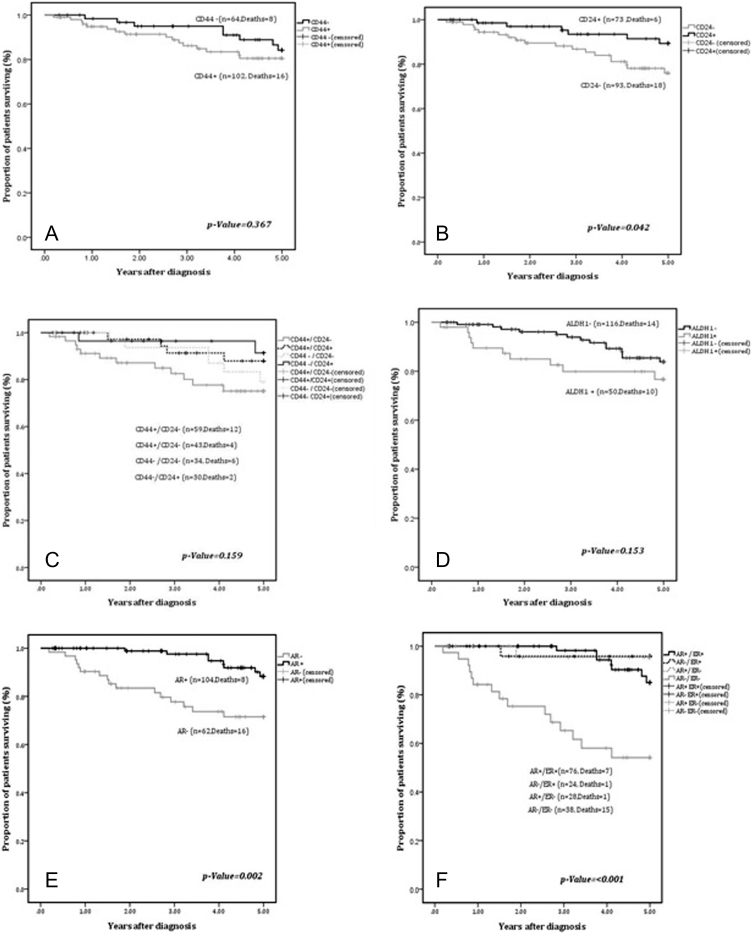

CD44 expressing tumors comprised of two groups: a) Expression observed in 1–10% of cells (26.5%); b) Expression observed in >10% of cells (35%). Expression of CD44 varied significantly amongst BCa subtypes (P = .018) with highest expression in luminal A (40.2%) and lowest in luminal B (11.8%) while 16.7% of Her2/neu+ and 31.4% of TNBC tumors expressed CD44. Furthermore, CD44+ tumors were significantly associated with positive expression of ER (P = .006) and low and intermediate grade (P = .021) tumors. However, no association was found with disease stage, axillary nodal status, PR, AR and HER-2/neu expression or amplification (P > .05). There was no significant difference in 5-year DFS of patients stratified by CD44 expression (P = .367) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

A-F: Kaplan Meier curves for 5-year DFS for expression of: A) CD44; B) CD24; C) CD44/CD24 phenotypes; D) ALDH1; E) AR; F) AR and ER.

CD24 expression

Amongst CD24+ tumors, 24.1% of cases exhibited expression in 1–10% of cells while >10% of positivity was demonstrated in remaining tumors (19.9%). No significant difference was observed between tumors with and without CD24 expression with respect to stage, axillary node status, grade, BCa subtypes, ER, PR and HER-2/neu expression (P= > 0.05). Significant concordant association was observed between AR and CD24 expressing tumors (P = .001). Remarkably, an adverse 5-year DFS was observed in patients with CD24− phenotype as compared to tumors with CD24+ phenotype (P = .042) (Figure 2B).

CD44+/CD24− phenotype vs CD44−/CD24+ Phenotype Expression

Cases were categorized into four groups based on CD44 and CD24 expression patterns. Group I: CD44+/CD24− (n = 59 cases); Group II: CD44+/CD24− (n = 43 cases); Group III: CD44−/CD24− (n = 34); Group IV: CD44−/CD24+(n = 30). The groups did not differ with respect to stage, axillary node status, histological grade, PR, HER-2/neu expression and BCa subtypes (P > .05). However, ER expression was more frequent in group II (P = .028). Similarly, AR was expressed in 76.7% of group II tumors as compared to 45.8% of group I tumors (p-value = 0.005). The 5-year DFS between the groups did not attain statistical significance (P = .159) (Figure 2C).

ALDH1

We did not observe a significant association of ALDH1 expression with stage, axillary node status and HER-2/neu expression (P > .05). Of the cohort of tumors negative for ALDH1 expression (n = 116), we found that a significant number were Grade I and II tumors (P = <0.002). A significant association of discordance was observed between ALDH1 and ER (ALDH1−/ER+: P = .005), PR (ALDH1−/PR+: P = .036) and AR (ALDH1−/AR+: P = .010). Five-year DFS did not differ significantly between ALDH1+ and ALDH1− tumors (P = .153) (Figure 2D).

Association of AR with clinico-pathological features and outcome

AR expression was significantly associated with intermediate histological grade, expression of ER, PR and CD24 (P < .001) and lack of ALDH1 expression (P = .010). No significant difference was observed between AR+ or AR− tumors with respect to age at diagnosis, tumor size, axillary lymph node status, stage, HER-2/neu over-expression or amplification and CD44 expression (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical and Histopathological Characteristics Stratified by AR Expression (n = 166)

| Features | AR Positive n = 104 (62.7) | AR Negative n = 62 (37.3) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis | |||

| <40 | 13 (12.5) | 7 (11.3) | 0.193 |

| 40–49 | 23 (22.1) | 22 (35.5) | |

| 50–59 | 23 (22.1) | 15 (24.2) | |

| 60–64 | 15 (14.4) | 9 (14.5) | |

| ≥ 65 | 30 (28.8) | 9 (14.5) | |

| Tumor Size | |||

| T1 | 16 (15.4) | 4 (6.5) | 0.082 |

| T2 | 49 (47.1) | 37 (59.7) | |

| T3 | 21 (20.1) | 16 (25.8) | |

| T4 | 18 (17.3) | 5 (8) | |

| Axillary Nodal Status | |||

| N0 | 54 (51.9) | 35 (56.5) | 0.844 |

| N1 | 28 (26.9) | 15 (24.2) | |

| N2 | 10 (9.6) | 7 (11.3) | |

| N3 | 12 (11.5) | 5 (8) | |

| Grade of Tumor | |||

| I | 13 (12.5) | 2 (3.2) | <0.001* |

| II | 71 (68.3) | 26 (41.9) | |

| III | 20 (19.2) | 34 (54.8) | |

| Stage of Disease | |||

| I | 20 (19.2) | 7 (11.3) | 0.324 |

| II | 55 (52.9) | 39 (62.9) | |

| III | 29 (27.9) | 16 (25.8) | |

| ER Expression | |||

| Positive | 76 (73.1) | 24 (38.7) | <0.001* |

| Negative | 28 (26.9) | 38 (61.3) | |

| PR Expression | |||

| Positive | 66 (63.5) | 21 (33.9) | <0.001* |

| Negative | 38 (36.5) | 41 (66.1) | |

| HER-2/neu Status | |||

| Positive | 32 (30.8) | 18 (29) | 0.813 |

| Negative | 72 (69.2) | 44 (70.9) | |

| CD44 Expression | |||

| Positive | 60 (57.7) | 42 (67.8) | 0.198 |

| Negative | 44 (42.3) | 20 (32.2) | |

| CD24 Expression | |||

| Positive | 56 (53.8) | 17 (27.4) | 0.001* |

| Negative | 48 (46.2) | 45 (72.6) | |

| ALDH1 Expression | |||

| Positive | 24 (23) | 26 (41.9) | 0.010* |

| Negative | 80 (76.9) | 36 (58) | |

| Triple Negative | |||

| Yes | 13 (12.5) | 20 (32.3) | 0.002* |

| No | 91 (87.5) | 42 (67.7) | |

Frequency of AR expression revealed significant variation across the BCa subtypes (P = <0.001). Amongst 104 (62.7%) AR+ tumors, AR expression was most frequently observed in luminal A (53.8%) and luminal B tumors (19.2%), followed by TNBC (15.3%) and HER-2/neu+ subtype (11.5%). Significantly better 5-year DFS was observed in patients with AR+ tumors as compared to patients with AR− tumors (P = .002) (Figure 2E). The concordant expression of AR and ER (AR+/ER+) associated with a significantly improved outcome (P < .001) as compared to concordantly negative tumors (AR−/ER−) (2F).

Univariate analysis revealed axillary nodal metastasis (crude HR 2.31, 95% CI 0.99–5.41; P = .046), stage III (crude HR 3.16, 95%CI 0.90–11.13; P = .002) and neo-adjuvant chemotherapy (crude HR 2.32, 95% CI 1.01–5.30; P = .040) to be associated with adverse outcome. Expression of ER (crude HR 0.28, 95% CI 0.12–0.64; P = .001), PR (crude HR 0.27, 95% CI 0.11–0.68; P = .003) and AR (crude HR 0.0.28, 95% CI 0.12–0.66; P = .002) predicted better outcome. Subsequent multivariable analysis confirmed ER (adjusted HR 0.35, 95% CI 0.14–0.85; P = .021) and AR expression (adjusted HR 0.33, 95% CI 0.13–0.81; P = .016) to be independently associated with improved outcome (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cox Univariable and Multivariable Analysis of Clinical and Pathological Variables for Mortality in Patients with Invasive BCa (n = 166)

| Variables | Crude Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis | ||||

| <40 | 1 | 0.909 | - | - |

| 40–49 | 0.81 (0.24–2.77) | |||

| 50–59 | 0.90 (0.26–3.08) | |||

| 60–64 | 0.46 (0.08–2.51) | |||

| >65 | 0.70 (0.18–2.82) | |||

| Tumor Grade | ||||

| I | 1 | 0.162 | - | - |

| II | 1.87 (0.24–14.28) | |||

| III | 3.64 (0.47–28.19) | |||

| Axillary Lymph Nodes | ||||

| Negative | 1 | 0.046 | - | - |

| Positive | 2.31 (0.99–5.41) | |||

| Stage of Disease | ||||

| I | 1 | 0.002 | 1 | 0.0028* |

| II | 0.80 (0.21–3.01) | 0.71 (0.18–2.67) | ||

| III | 3.16 (0.90–11.13) | 3.21 (0.92–11.29) | ||

| Adjuvant Chemotherapy | ||||

| No | 1 | 0.055 | - | - |

| Yes | 0.46 (0.20–1.03) | |||

| Neo-adjuvant Chemotherapy | ||||

| No | 1 | 0.040 | - | - |

| Yes | 2.32 (1.01–5.30) | |||

| Endocrine Therapy | ||||

| No | 1 | 0.003 | - | - |

| Yes | 0.29 (0.12–0.68) | |||

| ER Expression | ||||

| No | 1 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.021* |

| Yes | 0.28 (0.12–0.64) | 0.35 (0.14–0.85) | ||

| PR Expression | ||||

| No | 1 | 0.003 | - | - |

| Yes | 0.27 (0.11–0.68) | |||

| HER-2/neu | ||||

| Negative | 1 | 0.959 | - | - |

| Positive | 1.02 (0.42–2.47) | |||

| AR Expression | ||||

| Negative | 1 | 0.002 | 1 | 0.016* |

| Positive | 0.28 (0.12–0.66) | 0.33 (0.13–0.81) | ||

| CD44 Expression | ||||

| Negative | 1 | 0.368 | - | - |

| Positive | 1.47 (0.63–3.45) | |||

| CD24 Expression | ||||

| Negative | 1 | 0.042 | - | - |

| Positive | 0.39 (0.16–0.99) | |||

| ALDH1 Expression | ||||

| Negative | 1 | 0.153 | - | - |

| Positive | 1.79 (0.79–4.04) | |||

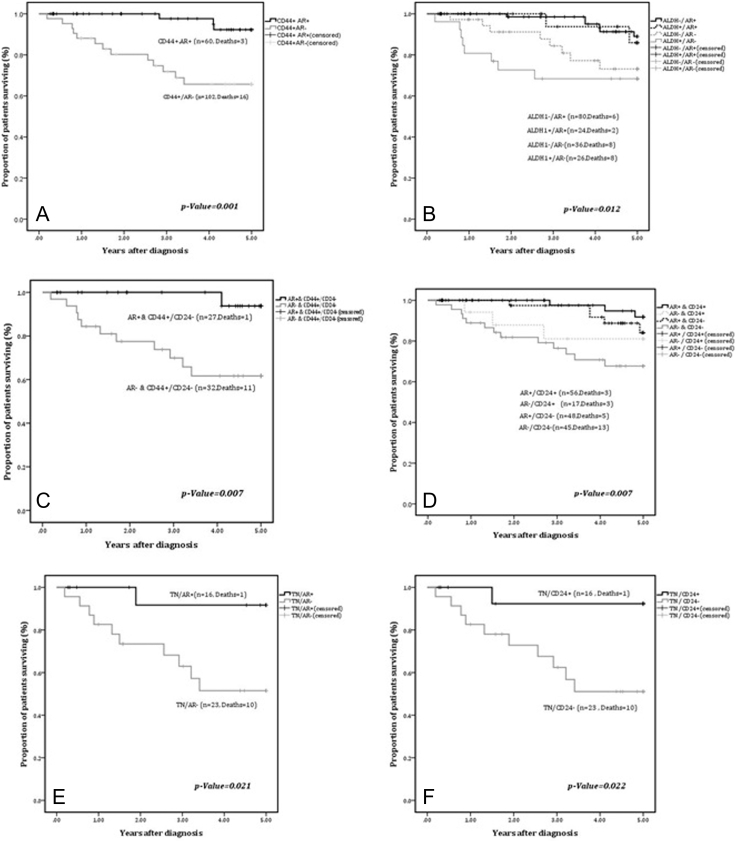

Impact of AR Expression On Survival In Tumors with Stem Cell Marker Expression

To investigate the prognostic relevance of AR in relation to CSC markers, we performed sub-group analysis where tumors identified with CSC phenotype were individually stratified for AR expression. We found that concordant expression of AR with CD44, ALDH1 and CD44+/CD24− phenotypes (CD44+/AR+, ALDH1+/AR+ and CD44+/CD24−/AR+, respectively) selected for a cohort of patients with a significantly better outcome. CD44+/AR+ tumors had a mean survival time of 4.9 ± 0.0.06 years as compared to CD44+/AR− tumors (3.9 ± 0.26 years) (P = .001). Similarly, ALDH1+/AR+ phenotype also demonstrated a better outcome with a mean survival time of 4.85± 0.13 years as compared to mean survival time of 3.79± 0.36 years in tumors with ALDH1+/AR− phenotype (P = .012). Likewise, AR expression in tumors with CD44+/CD24− cases was associated with significantly favorable outcome (P = .007) with mean survival time of 4.9 years±0.54 years as opposed to AR−/CD44+/CD24− cases with lower mean survival time (3.79± 0.36 years) (Figure 3A-C).

Figure 3.

A-F: Kaplan Meier curves for 5-year DFS for: A) CD44+ cases stratified by AR expression (n = 102); B) ALDH1 and AR expression (n = 166); C) AR and CD44+/CD24− phenotype (n = 59); D) CD24 and AR expression (n = 166); E & F) TNBC cases stratified by expression of AR and CD24.

Interestingly, concordant expression of AR and CD24 (CD24+/AR+) conferred a significant survival advantage (mean: 4.9 ± 0.05 years) as compared to tumors with AR−/CD24− phenotype (mean: 4.02± 0.24 years) (P = .007) (Figure 3D). Expression of AR and CD24 was also associated with a significant survival advantage in TNBC (P = .021 and P = .022 respectively) as shown in Figure 3E-F.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to date, examining the clinical significance of individual and combined expression of putative CSC phenotypes (CD44+, CD44+/CD24− and ALDH1+) together with AR on clinical samples of primary invasive BCa with its implications on patient survival.

Salient findings of our study of stage I-III invasive BCa are:

-

a)

Lack of association CSC phenotypes (CD44+, CD44+/CD24− and ALDH1+) with 5-year DFS;

-

b)

Patients with tumors expressing CD24 showed a significantly better 5-year DFS (P = .042);

-

c)

Significantly improved 5-year DFS survival observed in patients whose tumors expressed AR (P = .002);

-

d)

Patients with tumors expressing concordant AR and CD24 showed a significantly better 5-year DFS (P = .007).

In 2003, Al-Hajj and colleagues were the first to identify a CSC population in BCa with a CD44+/CD24−/Lin− phenotype [19]. Four years later in 2007, Ginestier and colleagues identified ALDH1+ CSC population in samples of normal and malignant breast epithelium [20]. Subsequently, the existence and potential relevance of CSCs with either CD44+/CD24− and ALDH1+ phenotypes were validated in several in vitro and in vivo studies [33], [34], [35]. In our study we did not observe a significant association of CSC phenotypes (CD44+/CD24− and ALDH1+) with 5-year DFS.

There are several potential explanations for these discrepant findings including the following:

-

a)

Influence of the tumor microenvironment: In vitro studies utilizing BCa cell lines and the serial transplantation assays are devoid of the tumor microenvironment (TME), whereas, the in vivo studies on patient tumor samples have a preserved TME. The CSC niche comprises of extra cellular matrix, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, perivascular cells and a myriad of signaling molecules including growth factor and cytokines [18]. The CSC niche plays a pivotal role in determining stem cell fate via cues from cell–cell interaction and paracrine factors [21]. It is therefore not surprising to observe discordant observations between in vitro and in vivo studies on patient tumor samples.

-

b)

CSCs exhibit phenotypic plasticity by their capacity to reversibly interconvert between a differentiated and stem cell fate [36]. It is therefore conceivable that a CSC with a CD44+/CD24− phenotype transitioned to a differentiated cell exhibiting CD24+ phenotype and further differentiating into a clone with CD24+/AR+ phenotype, thus becoming a dominant clone within the tumor likely associated with favorable outcome.

-

c)

Dormancy is yet another factor which should be taken into consideration in the evolution of tumor. It is perhaps conceivable that over the course of a longer follow up, the dormant CD44+/CD24−/low phenotype could transition from the state of quiescence into a phenotype capable of metastasis and hence poor outcome.

Hence the findings from our study coupled with those from the other studies should be interpreted with caution as there are several factors which influence these observations and conclusions.

With reference to expression of AR, our findings are in agreement with several previous studies signifying the prognostic relevance of AR as a powerful predictor of improved survival associated with small tumors, low grade and ER/PR expression [3], [5], [37], [38].

Our study has examined the immunohistochemical expression and prognostic implication of AR and CSC markers which has not been described before. The sub-group analysis has demonstrated a survival benefit with concordant expression of CD44 and AR (CD44+/AR+) as compared to tumors with a discordant expression phenotype (CD44+/AR−). Concordant expression of AR with ALDH1 (ALDH1+/AR+) and CD44+/CD24− (CD44+/CD24−/AR+) sub-groups also displayed a similar trend towards survival advantage. Only two studies have reported expression of AR with ALDH1 however, in both these studies no significant association was found between AR and ALDH1 [39], [40].

The mechanisms of biological interaction of AR signaling with CSC markers has been addressed in a few in vitro studies with inconsistent results. Zhang et al. demonstrated that ligand activated AR in MCF-7 inhibited tumor initiation, self-renewal and invasive potential via transcriptional up-regulation of Let 7a [12]. In contrast, Feng et al. demonstrated that AR signaling in MCF-7 induced epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) program with enhanced invasion, migration, self-renewal and enrichment of CD44+/CD24− phenotype [27]. Barton et al. provided evidence demonstrating that AR mRNA, protein and transcriptional activity increased under anchorage independent conditions using TNBC cell lines and AR inhibition by enzalutamide decreased CSC population [14]. Although these studies add to the understanding of AR and CSC interaction, however, AR signaling pathways regulating CSC across the various molecular subtypes of BCa require further insight.

CD24 is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked cell adhesion protein expressed in several malignancies including BCa [41]. We found that its expression in tumors was associated with significantly better survival (P = .042) that was enhanced when there was concordant expression with AR (P = .007). Bensimon et al. demonstrated that CD24− cells had lower proliferation rates, lower levels of reactive oxygen species and decreased genomic stability whereas CD24+ tumors showed the converse, concluding that the loss of CD24 leads to radiation resistance [42], [43]. Ju et al. showed that forced expression of CD24 in MDA-MB231 resulted in decreased proliferation, down-regulation of cRAF /MEK/MAPK pathway and increased apoptosis through inhibition of NF-ƙB signaling pathway [44]. This contrasts with immunohistochemical studies of Kristiansen et al. and Kwon et al. demonstrating CD24 as a poor prognostic marker [41], [45]. These conflicting data are probably due to the differing experimental approaches, factors related to tissue fixation, immunohistochemical cutoff points and genetic background of patients, amongst others.

In TNBC tumors we found that AR and CD24 conferred a survival advantage. Role of AR in these aggressive tumors requires further elucidation as data on the potential role of AR in TNBC is equivocal. AR expression in TNBC has been associated with older age, advanced disease, lymph node metastasis, high Ki-67, lymphovascular invasion, and poor survival [15], [16], [39]. Conversely, other studies have demonstrated that AR expression in TNBC correlates with well-differentiated tumors with decreased incidence of lymph node metastasis and better survival [46]. Likewise, CD24 expression has been associated with either adverse outcome or has failed to show any association with survival in TNBC [45]. Biological interaction between AR and CD24 has been demonstrated in bladder cancer, where CD24 transcriptional activity was enhanced via ligand activated AR through its interaction with androgen response elements located upstream of CD24 promoter [47]. Significance of AR and CD24 in BCa requires further elucidation.

The limitations of our study include: a) Small sample size: In Pakistan, as in most low/middle income countries, patients are either lost to follow up or attend different institutions for treatment, which makes it challenging to undertake long term survival studies on a large cohort of patients; b) Undertaking single as opposed to double immunostaining which may have identified the various co-expressing population of cells with a higher precision.

Conclusions

In our study, amongst the analyzed biomarkers, only AR and CD24 significantly correlated with favorable clinicopathological features and an improved survival whereas CSC markers such as CD44+, CD44+/CD24− and ALDH1+ were not effective prognostic indicators for outcome prediction.

These findings are contributory to existing literature where AR has emerged as an important prognostic marker in BCa with promising therapeutic application. Studies on larger cohorts are warranted for substantiation of our results. Moreover, routine assessment of AR in BCa may provide valuable insight for disease prognostication and for identification of low-risk patient population.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

Details of antibodies, antigen retrieval, dilution and detection methodology.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contributions of the following individuals: Dr Azhar Hussain and Sheerien Rajput for critical review of the manuscript and generosity of several donors for partial funding support towards this project.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: None.

Funding: University Research Council Grant of the Aga Khan University (122014 P & M).

Contributor Information

Nazia Riaz, Email: nazia.riaz@aku.edu.

Romana Idress, Email: romana.idress@aku.edu.

Sadia Habib, Email: sadia.habib@aku.edu.

Iqbal Azam, Email: iqbal.azam@aku.edu.

El-Nasir MA Lalani, Email: elnasir.lalani@aku.edu.

References

- 1.Pietri E, Conteduca V, Andreis D, Massa I, Melegari E, Sarti S, Cecconetto L, Schirone A, Bravaccini S, Serra P. Androgen receptor signaling pathways as a target for breast cancer treatment. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2016;23(10):R485–R498. doi: 10.1530/ERC-16-0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bozovic-Spasojevic I, Zardavas D, Brohee S, Ameye L, Fumagalli D, Ades F, de Azambuja E, Bareche Y, Piccart M, Paesmans M. The Prognostic Role of Androgen Receptor in Patients with Early-Stage Breast Cancer: A Meta-analysis of Clinical and Gene Expression Data. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(11):2702–2712. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qu Q, Mao Y, Fei XC, Shen KW. The impact of androgen receptor expression on breast cancer survival: a retrospective study and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins LC, Cole KS, Marotti JD, Hu R, Schnitt SJ, Tamimi RM. Androgen receptor expression in breast cancer in relation to molecular phenotype: results from the Nurses' Health Study. Mod Pathol. 2011;24(7):924–931. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vera-Badillo FE, Templeton AJ, de Gouveia P, Diaz-Padilla I, Bedard PL, Al-Mubarak M, Seruga B, Tannock IF, Ocana A, Amir E. Androgen receptor expression and outcomes in early breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(1) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu Q, Niu Y, Liu N, Zhang JZ, Liu TJ, Zhang RJ, Wang SL, Ding XM, Xiao XQ. Expression of androgen receptor in breast cancer and its significance as a prognostic factor. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(6):1288–1294. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castellano I, Allia E, Accortanzo V, Vandone AM, Chiusa L, Arisio R, Durando A, Donadio M, Bussolati G, Coates AS. Androgen receptor expression is a significant prognostic factor in estrogen receptor positive breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;124(3):607–617. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0761-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loibl S, Muller BM, von Minckwitz G, Schwabe M, Roller M, Darb-Esfahani S, Ataseven B, du Bois A, Fissler-Eckhoff A, Gerber B. Androgen receptor expression in primary breast cancer and its predictive and prognostic value in patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130(2):477–487. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1715-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sultana A, Idress R, Naqvi ZA, Azam I, Khan S, Siddiqui AA, Lalani EN. Expression of the Androgen Receptor, pAkt, and pPTEN in Breast Cancer and Their Potential in Prognostication. Transl Oncol. 2014;7(3):355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Need EF, Selth LA, Harris TJ, Birrell SN, Tilley WD, Buchanan G. Research resource: interplay between the genomic and transcriptional networks of androgen receptor and estrogen receptor alpha in luminal breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26(11):1941–1952. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cochrane DR, Bernales S, Jacobsen BM, Cittelly DM, Howe EN, D'Amato NC, Spoelstra NS, Edgerton SM, Jean A, Guerrero J. Role of the androgen receptor in breast cancer and preclinical analysis of enzalutamide. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16(1):R7. doi: 10.1186/bcr3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rangel N, Rondon-Lagos M, Annaratone L, Osella-Abate S, Metovic J, Mano MP, Bertero L, Cassoni P, Sapino A, Castellano I. The role of the AR/ER ratio in ER-positive breast cancer patients. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2018;25(3):163–172. doi: 10.1530/ERC-17-0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang C, Pan B, Zhu H, Zhou Y, Mao F, Lin Y, Xu Q, Sun Q. Prognostic value of androgen receptor in triple negative breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7(29):46482–46491. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barton VN, D'Amato NC, Gordon MA, Lind HT, Spoelstra NS, Babbs BL, Heinz RE, Elias A, Jedlicka P, Jacobsen BM. Multiple molecular subtypes of triple-negative breast cancer critically rely on androgen receptor and respond to enzalutamide in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14(3):769–778. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi JE, Kang SH, Lee SJ, Bae YK. Androgen receptor expression predicts decreased survival in early stage triple-negative breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(1):82–89. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3984-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGhan LJ, McCullough AE, Protheroe CA, Dueck AC, Lee JJ, Nunez-Nateras R, Castle EP, Gray RJ, Wasif N, Goetz MP. Androgen receptor-positive triple negative breast cancer: a unique breast cancer subtype. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(2):361–367. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu R, Dawood S, Holmes MD, Collins LC, Schnitt SJ, Cole K, Marotti JD, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Tamimi RM. Androgen receptor expression and breast cancer survival in postmenopausal women. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(7):1867–1874. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plaks V, Kong N, Werb Z. The cancer stem cell niche: how essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16(3):225–238. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(7):3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ginestier C, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E, Monville F, Dutcher J, Brown M, Jacquemier J, Viens P, Kleer CG, Liu S. ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(5):555–567. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreso A, Dick JE. Evolution of the cancer stem cell model. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14(3):275–291. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin Y, Zhong Y, Guan H, Zhang X, Sun Q. CD44+/CD24- phenotype contributes to malignant relapse following surgical resection and chemotherapy in patients with invasive ductal carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2012;31:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-31-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mylona E, Giannopoulou I, Fasomytakis E, Nomikos A, Magkou C, Bakarakos P, Nakopoulou L. The clinicopathologic and prognostic significance of CD44+/CD24(−/low) and CD44-/CD24+ tumor cells in invasive breast carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2008;39(7):1096–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ali HR, Dawson SJ, Blows FM, Provenzano E, Pharoah PD, Caldas C. Cancer stem cell markers in breast cancer: pathological, clinical and prognostic significance. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13(6):R118. doi: 10.1186/bcr3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmed MA, Aleskandarany MA, Rakha EA, Moustafa RZ, Benhasouna A, Nolan C, Green AR, Ilyas M, Ellis IO. A CD44(−)/CD24(+) phenotype is a poor prognostic marker in early invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133(3):979–995. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1865-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang W, Liu X, Liu S, Qin Y, Tian X, Niu F, Liu H, Liu N, Niu Y. Androgen receptor/let-7a signaling regulates breast tumor-initiating cells. Oncotarget. 2018;9(3):3690–3703. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng J, Li L, Zhang N, Liu J, Zhang L, Gao H, Wang G, Li Y, Zhang Y, Li X. Androgen and AR contribute to breast cancer development and metastasis: an insight of mechanisms. Oncogene. 2017;36(20):2775–2790. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barton VN, Christenson JL, Gordon MA, Greene LI, Rogers TJ, Butterfield K, Babbs B, Spoelstra NS, D'Amato NC, Elias A. Androgen Receptor Supports an Anchorage-Independent, Cancer Stem Cell-like Population in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77(13):3455–3466. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM, Statistics Subcommittee of NCIEWGoCD REporting recommendations for tumor MARKer prognostic studies (REMARK) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100(2):229–235. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Honeth G, Bendahl PO, Ringner M, Saal LH, Gruvberger-Saal SK, Lovgren K, Grabau D, Ferno M, Borg A, Hegardt C. The CD44+/CD24- phenotype is enriched in basal-like breast tumors. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10(3):R53. doi: 10.1186/bcr2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Resetkova E, Reis-Filho JS, Jain RK, Mehta R, Thorat MA, Nakshatri H, Badve S. Prognostic impact of ALDH1 in breast cancer: a story of stem cells and tumor microenvironment. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123(1):97–108. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0619-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allred DC, Harvey JM, Berardo M, Clark GM. Prognostic and predictive factors in breast cancer by immunohistochemical analysis. Mod Pathol. 1998;11(2):155–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charafe-Jauffret E, Ginestier C, Iovino F, Wicinski J, Cervera N, Finetti P, Hur MH, Diebel ME, Monville F, Dutcher J. Breast cancer cell lines contain functional cancer stem cells with metastatic capacity and a distinct molecular signature. Cancer Res. 2009;69(4):1302–1313. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheridan C, Kishimoto H, Fuchs RK, Mehrotra S, Bhat-Nakshatri P, Turner CH, Goulet R, Jr., Badve S, Nakshatri H. CD44+/CD24- breast cancer cells exhibit enhanced invasive properties: an early step necessary for metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8(5):R59. doi: 10.1186/bcr1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li W, Ma H, Zhang J, Zhu L, Wang C, Yang Y. Unraveling the roles of CD44/CD24 and ALDH1 as cancer stem cell markers in tumorigenesis and metastasis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14364-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quail DF, Taylor MJ, Postovit LM. Microenvironmental regulation of cancer stem cell phenotypes. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2012;7(3):197–216. doi: 10.2174/157488812799859838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Basile D, Cinausero M, Iacono D, Pelizzari G, Bonotto M, Vitale MG, Gerratana L, Puglisi F. Androgen receptor in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer: Beyond expression. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;61:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park S, Koo J, Park HS, Kim JH, Choi SY, Lee JH, Park BW, Lee KS. Expression of androgen receptors in primary breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(3):488–492. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pistelli M, Caramanti M, Biscotti T, Santinelli A, Pagliacci A, De Lisa M, Ballatore Z, Ridolfi F, Maccaroni E, Bracci R. Androgen receptor expression in early triple-negative breast cancer: clinical significance and prognostic associations. Cancers (Basel) 2014;6(3):1351–1362. doi: 10.3390/cancers6031351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elebro K, Bendahl PO, Jernstrom H, Borgquist S. Androgen receptor expression and breast cancer mortality in a population-based prospective cohort. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;165(3):645–657. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4343-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kristiansen G, Winzer KJ, Mayordomo E, Bellach J, Schluns K, Denkert C, Dahl E, Pilarsky C, Altevogt P, Guski H. CD24 expression is a new prognostic marker in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(13):4906–4913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bensimon J, Biard D, Paget V, Goislard M, Morel-Altmeyer S, Konge J, Chevillard S, Lebeau J. Forced extinction of CD24 stem-like breast cancer marker alone promotes radiation resistance through the control of oxidative stress. Mol Carcinog. 2016;55(3):245–254. doi: 10.1002/mc.22273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bensimon J, Altmeyer-Morel S, Benjelloun H, Chevillard S, Lebeau J. CD24(−/low) stem-like breast cancer marker defines the radiation-resistant cells involved in memorization and transmission of radiation-induced genomic instability. Oncogene. 2013;32(2):251–258. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ju JH, Jang K, Lee KM, Kim M, Kim J, Yi JY, Noh DY, Shin I. CD24 enhances DNA damage-induced apoptosis by modulating NF-kappaB signaling in CD44-expressing breast cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(10):1474–1483. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kwon MJ, Han J, Seo JH, Song K, Jeong HM, Choi JS, Kim YJ, Lee SH, Choi YL, Shin YK. CD24 Overexpression Is Associated with Poor Prognosis in Luminal A and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rakha EA, El-Sayed ME, Green AR, Lee AH, Robertson JF, Ellis IO. Prognostic markers in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer. 2007;109(1):25–32. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Overdevest JB, Knubel KH, Duex JE, Thomas S, Nitz MD, Harding MA, Smith SC, Frierson HF, Conaway M, Theodorescu D. CD24 expression is important in male urothelial tumorigenesis and metastasis in mice and is androgen regulated. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(51):E3588–E3596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113960109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Details of antibodies, antigen retrieval, dilution and detection methodology.