Short abstract

Objective

There is growing emphasis on health care organizations to ensure that lay people are meaningfully engaged as partners on research teams. Our aim was to explore the perspectives of patients, family members and informal caregivers who have been involved on health care research teams in Canada and elicit their recommendations for meaningful engagement.

Methods

We conducted a qualitative study guided by thematic analysis of transcripts of focus groups and interviews of 19 experienced patient research partners in Canada.

Results

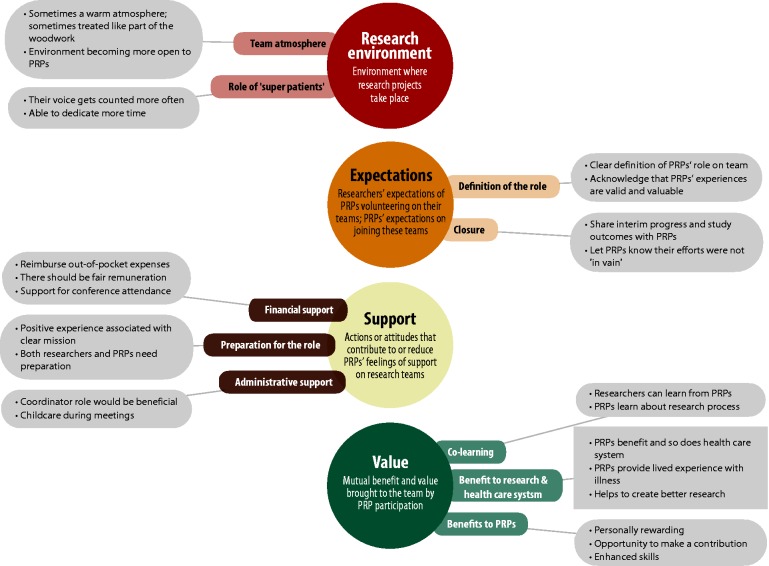

We identified four main themes: research environment, expectations, support and value, which highlight participants’ combined perspectives on important factors to ensure their engagement in research is meaningful.

Conclusions

Our findings add to the evolving evidence base on the perspectives of lay people involved in health care research and their recommendations for research leaders on meaningful engagement. Our study suggests that research leaders should provide a welcoming research environment, outline appropriate expectations for patient research partners on research teams, support patient research partners’ engagement in projects and recognize the value patient research partners bring to health research.

Keywords: patient and family engagement, patient engagement in research, patient experience, patient-oriented research, qualitative methods, research priority setting

Introduction

There is growing interest in engaging patients, their family members and other informal caregivers in both health care improvement and research in Canada.1,2 Patient engagement3–5 or patient and public involvement in research5–7 can cover the entire spectrum from individual patients and caregivers acting as consultants, advisors, collaborators or project leaders in the research process. This reflects an ideological shift towards partnering with those most affected by health research as key stakeholders in deciding what and how research is undertaken,7,8 and it is an increasingly important requirement by funders of health research in many countries.6,9,10 We here refer to patients, family members and informal caregivers who engage in research as patient research partners (PRPs).

Patient engagement in research is expected to empower PRPs and enhance research relevance to patients’ needs and preferences, quality and impact on health care policy and practice.11,12 However, ongoing discussion and empirical research have highlighted the need for more diversity among PRPs.2,5,7,13 Furthermore, recent systematic reviews on the impact of patient engagement in research show that the practice is feasible but tends to be tokenistic and lacks validated methods for meaningful engagement of PRPs.3,12,14

There is a growing body of literature on how to plan, implement and evaluate patient engagement in research.3,11,12,15–17 Existing guidance includes principles and recommendations for engaging PRPs and reporting their impact.6,17–19 The principles vary, but commonly incorporate core values such as trust, respect, transparency, reciprocal relationships, co-building and support.9,19,20 There are models and frameworks for proposed best practices.11,16 An example is the GRIPP2 (Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public) checklist, which provides guidance for reporting key aspects of patient and public involvement in research to enhance its evidence base internationally.18

The changing requirements from funding organizations, and the growing mandate for inclusion of the patient voice in research, create a more conducive environment for partnerships between PRPs and researchers across the life course of a study and research programmes.9,10,21 The perspectives of stakeholders, including PRPs, are seen to be valuable and should be included in research.16 In 2011, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research created the Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR), which led to the formation of 10 units across Canada, mandated to provide logistical support for patient-oriented research. A 2016 report from the SPOR SUPPORT Unit in British Columbia, Canada, showed that researchers had a strong interest but needed training and support in effectively engaging PRPs in research.22

While there is a growing body of literature on patient engagement in research, there is little robust evidence on the Canadian context.5,7,13,16,20,23 To address this gap, we explored the perspectives of patients and informal caregivers in Canada who have been involved on health care research teams and elicited their recommendations for meaningful engagement.

Methods

We used a qualitative methodological approach involving focus groups and interviews to explore the experiences and preferences of PRPs for engaging on health research teams. Our research team included two PRPs as co-researchers, both with previous experience partnering on research studies, who engaged at every stage of the study, from its inception through writing this manuscript. Each team member signed a team agreement describing their roles and responsibilities in the research project. The University of British Columbia-Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board (H16-00054) approved this study.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited between April and June 2016 using social media, targeted email announcements and the distribution of a promotional flyer. Patient engagement organizations like Patient Voices Network emailed their membership, and we asked SPOR Units to advertise the study. Additionally, we contacted patients and informal caregivers from our personal networks and conducted snowball sampling.24 Interested potential participants completed an eligibility screening questionnaire. Eligible individuals were patients or informal caregivers such as patients’ family members, who had contributed to research within the last five years as advisors, research team members or research priority-setting group members. Demographic information was collected on the screening questionnaire for selective sampling, but a low response rate resulted in the use of a convenience sample. All eligible individuals were invited to register for a focus group.

Focus groups and interviews

Eligible individuals chose to attend one of four scheduled focus groups, either in person, by teleconference or via a video-webinar platform. Three individuals who were unable to join a focus group participated in one-on-one interviews. Two teleconferences and a webinar made the focus groups accessible to participants across Canada.25 Participants provided written consent and anonymized demographic information before their focus groups or interviews. In-person participation occurred in a meeting room. Participants in the teleconferences called a toll-free phone number. Participants in the webinar logged in from personal computers.

Focus groups were co-facilitated by CBH and WYC, and WYC conducted the interviews. Participants were asked about aspects of their participation on research teams including preparation, role, support, challenges, benefits, expectations and outcomes (see Appendix 1 for interview guide). Participants were asked to make recommendations to improve engagement of PRPs on research teams. After each focus group, the facilitators met and compiled field notes. All focus groups and interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim and de-identified to maintain anonymity.

Data analysis

We conducted a thematic analysis guided by the six-step Thematic Network Analytical Technique.26 This allowed inductive and systematic identification of nascent themes across three levels: basic themes, organizing themes and global themes. Higher level themes were conceptual abstractions of ideas consistent across themes from the previous level.26

In Step 1, all team members independently open-coded the same transcript from a focus group. The team met, discussed and refined the codes. Each team member coded the remaining transcripts and then took a consecutive week to revise the evolving coding framework. In Step 2, we discussed the codes at team meetings, allowing themes to emerge from the interpretive lenses of all team members. Key codes were selected, and themes abstracted from the corresponding quotes. In Step 3, we finalized the arrangement of themes across the three thematic levels (basic, organizing and global), by removing, combining and renaming some themes. Field notes provided further context during data organization and theming. We gave priority to themes that were more common and themes the PRPs on our team felt were crucial to the viewpoints of PRPs. In Step 4, each global theme with supporting themes was described using corresponding quotes. In Step 5, our team created summaries for each thematic network. Finally, in Step 6, we explored and interpreted the relationships among the thematic networks, which involved comparison of our results to important attributes of patient engagement on research teams as emphasized in published literature. The research team agreed on a cohesive set of recommendations arising from participants’ responses to focus group and interview questions. This paper was initially written by ATB and CBH and then critically reviewed and approved by our entire research team.

Results

Our study included 19 PRPs from three Canadian provinces. Individuals chose to attend one of four focus groups, either in person (n = 4), by teleconference (n = 9) or via video-webinar platform (n = 3); or an interview (n = 3). Participants included 10 women and 9 men between the ages of 19 and 85 years. Sixteen participants identified as Caucasian, two as African-Canadian and one as Asian. At least nine participants had some university education; six participants provided no information on their educational level. Most of the participants (n = 9) had not received training for their research roles; of the remaining participants, seven had received training and three did not provide information on this. Eleven participants identified as patients, 10 as family members, 7 as informal caregivers (9 participants identified as more than one role). We identified four thematic networks, with the following respective global themes: research environment, expectations, support and value, which we describe in turn (Figure 1). Appendix 2 provides an overview of additional salient quotes from participants.

Figure 1.

Emergent Themes from the Perspectives of Patient Research Partners.

Research environment

Participants viewed the environment in which research projects take place as a key factor for meaningful engagement in research. Participants expressed that the research environment had changed in recent years to become more open to patient engagement. Organizing themes contributing to this global theme were team atmosphere and the role of ‘super patients’.

Team atmosphere

Participants indicated that the team atmosphere had a substantial impact on their experience. Some participants described a positive team atmosphere where they were welcomed and introduced, while others noted a team atmosphere in which team members were dismissive of the PRP. One participant said, ‘Some people are more open to hearing what you have to say and some people just treat you like you’re part of the woodwork’ (P15). Another participant commented on inequity within research teams: ‘I think there is this real sense of a power imbalance when you’re sitting around a room with…10 or 15 other individuals, all of whom have the title ‘doctor’…’ (P7).

One participant commented on the change in research atmosphere in recent years: ‘It’s really becoming a time of like ‘nothing about me without me’ and I think that it’s time that that be embraced within the research community…Unless you ask that patient you really don’t know what’s important’ (P12).

Role of ‘super patients’

At one focus group meeting, a participant commented that the research environment was impacted by the participation of ‘super patients’, who have more time to dedicate to volunteering on health care teams, and whose voices may get counted more often. Other participants nodded in agreement, and the participant went on to state their view that if research teams become too dependent on ‘super patients’ they would miss the perspectives of patients and informal caregivers from more marginalized groups and suggested, ‘…we must look at…the social determinants and how they interplay with patient engagement’ (P18).

Expectations

Many participants had strong views on the expectations of researchers leading health care teams, and some perceived that researchers’ expectations of PRPs were not always realistic, equitable or well-articulated to the PRPs. The organizing themes were definition of the role and closure.

Definition of the role

Several participants commented that research teams on which they volunteered were unclear about the roles of the PRPs. For example, one participant noted, ‘I remember asking…‘What’s my role on the governing council?’ and she said… ‘I don’t know! We’re going to figure that out as we go’’ (P7). This participant also commented that other team members seemed unsure about how to relate to the PRPs: ‘…people again are very open to having me there…. But I think a little bit unclear as to ‘what is this person doing who is not a trained academic?’’ (P7) Advice from one participant was, ‘I think it should be made clear to people that your primary role here as a patient is to bring your personal experiences. Your experiences…are valuable’ (P3). Several participants described positive experiences of having clearly defined roles, including one participant who said, ‘My experience is very, very positive…. we have specific roles that are recognized by the organization…We have terms of reference, we have a mission’ (P13).

Closure

Participants had strong expectations that research team leaders should report back to them on the results of research projects:

If I had to say a weakness on a majority of studies that I’ve taken part in… The results of the study either are promised and they don’t come through or they come through three years later… Closure is one of the things that I would emphasize…without it, again you wonder about your value. (P2)

Another participant echoed this sentiment: ‘Follow up after a study is completed is something that is sorely lacking…I think it is a massive way in creating value for people participating in the research…Just show them that their efforts weren’t in vain…’ (P3).

Support

When asked about support for PRPs, participants listed various actions and attitudes of other team members and team leaders that either enhanced or lessened their feelings of support on teams. One participant stated: ‘I don’t get the impression that I’m really supported in the same way as the researchers are supported, you know… You’re sort of doing it all by yourself ’ (P16). Three organizing themes emerged: financial support, preparation/training for the role and administrative support.

Financial support

Many participants believed that research team leaders should cover engagement-related costs (parking, mileage and food), and some participants noted their appreciation for payment they received for their assistance on research teams, or desire to be paid for their work on research teams. One participant commented on experienced inequities of support between the PRPs and other stakeholders on research teams:

The number of times that I have sat in a room as a volunteer on a committee or various projects where everyone in the room was being paid except for myself…I think that there should be fair remuneration for the work that a person does…it doesn’t inspire people to contribute and to put in the effort, you know, if they’re not being paid for travel and for their costs at a bare minimum… (P3)

Funding PRPs to attend conferences was felt to be another missed opportunity to offer support: ‘I don’t have the same opportunity for conferences…’ (P16). The same participant expressed that if researchers value the role of PRPs, they should be compensated: ‘Everybody else in the room is getting paid, so maybe they don’t value what they don’t pay for’ (P16). One other participant recounted the experience of a PRP colleague: ‘She was paid nothing…But instead they dumped on her 12 hours of work…and she thought, ‘This is not fair. The doctors are getting several hundred dollars and I’m getting a Thank You…’’ (P2).

One participant expressed concern that payment for the work could jeopardize their disability status: ‘If you are on like, government support in any way and if you receive income, they will dock half of your income’ (P18). In contrast, one other participant described being paid for assisting a research team: ‘In the second research team I’m involved with I get an hourly wage for the work that I do. So, I feel, you know, I am a fully valued member of this team…’ (P6). Although our participants were not in agreement about all aspects of financial support, they were unified in expressing that the costs of their engagement, such as parking and meals, should be covered.

Preparation/training for the role

Participants expressed widely divergent experiences with the preparation and training for their roles but agreed that preparation was beneficial and recommended, both for PRPs and for researchers, who often seemed unprepared for working with PRPs. Among participants who felt inadequately prepared, a typical comment was: ‘I could have used a lot of orientation to what health research is, how it operates in Canada, how it’s funded…in order to…get my feet under me and feel that I was an equal contributor at the table’ (P7). One participant described feeling unprepared and out of place at their first research team meeting:

Well, the first formal research team meeting that I went to, the only preparation that I had was a one-page description of the research they were doing. And when I went into the room…with one page only and the rest of them had stacks of papers in front of them, I felt very unprepared…It’s like you’re on their turf…and as friendly as they try to be, if you’re not well-prepared you really don’t want to open your mouth and sound stupid… (P16)

Among participants who felt prepared for their roles, one participant described receiving a half-day orientation session, while others noted having taken the initiative themselves by signing up for on-line courses. One participant who felt well supported in her role noted: ‘My experience was nothing but amazing… They fly you in. They have you for dinner the night before the review with all the reviewers. So you have an opportunity to meet as human beings and just talk’ (P12). Participants agreed that preparation and training for the role of PRP benefits the entire research team by supporting smoother integration of the PRPs onto the team.

Administrative support

Participants noted a variety of supports that they felt would be helpful to them, including childcare during meetings and coordinators to assist them in their roles as PRPs. One participant said:

For us it was really important that they were able to provide childcare because, you know, the expenses when you have a child with a medical condition or disability or something like that – you can’t get just the neighbourhood 12-year-old to come and take care of them, so those expenses can be pretty intensive. (P10)

One participant noted that the local hospital had a coordinator who manages engagement requests and matches patients and family members with research teams looking for patient input. Another participant suggested that they would welcome the coordinator role: ‘I would like to suggest that there be a position like a coordinating position, someone that can coordinate relationships with patients and family partners and the rest of the research teams…a go-to person for support’ (P7).

Value

PRPs described the perceived value of their engagement on research teams, including benefits they felt their participation offered to the teams, and the benefits they received from participation. Within the global theme of value, we identified three organizing themes: co-learning, benefit to research and the health care system and benefits to the PRPs.

Co-learning

Participants explained that their engagement in research taught them a great deal and they felt that the researchers had also learned from them. One participant shared their experience of interpreting and communicating research information. ‘So by having us there…to say ‘what does that mean?’ was actually pretty helpful to them to recognize that they need to use simple language when they’re trying to get information across to a broad audience’ (P10).

Benefit to research and the health care system

Most of the participants’ reasons for volunteering to engage in research included potential benefits to other patients and the health care system. ‘I do it because I will benefit if the health system benefits’ (P2). Those ideas were shared by other participants who stated: ‘The reason I got into the volunteering is to make the experience better than it was for me in those early days so that…the new families that are coming up won’t have such a broken experience’ (P11).

There was the sense that PRPs ‘…can certainly help to create better research…’ (P3) and expressions of appreciation when researchers acknowledged the importance of their contributions. Participants felt strongly that patients bring their experiences of living with illness and that researchers would benefit from those experiences:

It was really very important for patients to be involved in that review process because the reviewers…don’t necessarily have the knowledge of living with the disease and the patients brought that to the table and while at first the reviewers were not really accepting…by the end of the day we were very much accepted as part of the process… (P9)

Additionally, participants noted that they would bring a range of skills to their PRP role, including social media abilities, experience as educators and writing for publication, all of which they believed could assist their research teams in multiple ways.

Benefits to the PRPs

Almost all participants noted that their engagement in research had benefitted them personally. ‘I find it incredibly interesting and personally rewarding… Because of my health, I had had to retire from my full-time job and I was really missing having some meaningful work in my life…’ (P7). One participant stated: ‘One of the benefits to me is the opportunity to have input into shaping any number of different things that I or others in similar situations might be able to benefit from’ (P19). Participants noted other benefits, such as enhanced communication skills gained through the experience of presenting and writing along with the research team. Participants also benefited from ‘…getting to know the community a little more’ (P13).

Based on their experiences, this study provides advice for research team leaders and health care leaders seeking to initiate or continue engaging PRPs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Recommendations for leaders, researchers and patient research partners (PRPs).

| Themes | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Research environment |

|

| Expectations |

|

| |

| Support |

|

| |

| |

| |

| Value |

|

Discussion

This paper describes the perspectives and recommendations of PRPs on health care research teams in Canada. Study participants reinforced the need to improve patient engagement in research, particularly across four broad factors: research environment, expectations, support and value.

We found benefits to PRPs and researchers from a research environment that provides a positive team atmosphere, which is consistent with recommendations in models such as ‘Facilitate, Identify, Respect, Support, Trust’ (FIRST).20 The FIRST model emphasizes facilitating PRPs’ engagement by ‘creating practical conditions and eliminating barriers for structural collaboration’.20 Existing guidelines for engaging patients in research have highlighted that supportive attitudes of stakeholders towards engagement are paramount for its progress.19 In a positive team atmosphere, PRPs are treated with respect19,20,27 and as important partners rather than as ‘part of the woodwork’ (P15).

Our findings contribute the unique notion of ‘super patients’, referring to individuals who contribute frequently to research engagement opportunities, thus enabling their voices to be included multiple times. The concept of ‘super patients’ is related to concerns about ‘socialization’ of some PRPs to their role on research teams, and the potential loss of their ability to represent a layperson’s point of view if they receive formal training and research experience.28 Qualitative studies in the UK have highlighted a need for greater diversity among PRPs, such as ability, age, class, gender, geography, ethnicity/race, immigration status, indigeneity, sexuality and religion.2,7,13 While ‘super patients’ could be an important driving force for increasing patient engagement in research, issues of diversity and professionalization among PRPs should be addressed.2,7,13 Practical solutions for research leaders include the suggestion to recruit a diversity of patient perspectives pulled from the population being studied, and at least two PRPs per research team.28,29

PRPs participating in this research wanted research leaders to provide them with clearly defined roles and expectations, which is part of acknowledging the value they bring to research.16,20,23 Published research has recommended that PRPs and research team leaders discuss the goals and expectations for the project at the outset.29 This could counter PRPs becoming frustrated with the slow progress of achieving results from research.13 Our findings emphasize an expectation for closure, in which research leaders report back to the PRPs on the progress and outcomes of a research project, such as with interim reports. This recommendation aligns with the evolving expectations for dissemination of research findings as put forth by health care funding agencies, such as the Canadian Institutes of Health Research in its Health Roadmap II.30

The need for support forms a strong element in guiding principles and models on patient engagement in research10,16,19,20,27 and underscores the importance of providing PRPs with preparation, training and financial resources to facilitate their contributions. Effective support could be addressed through formal or task-specific training.6,16 Participants also recommended that a coordinator could serve as go-between, who facilitates patient engagement in research. In describing a theoretical framework for mapping and evaluating patient and public involvement in health services research, Gibson et al. highlighted that an involvement coordinator helped to support the engagement of a patient advisory group.15 While most of our participants favoured reimbursement for out-of-pocket expenses, others were concerned that direct payment could negatively impact their government disability benefits. This mix of opinions on financial support is well documented in the literature.6,13,20 Some of our participants felt that research team leaders should simply ask PRPs about their preferences regarding payment.

Participants recognized that their personal perspectives could offer value to the research and potentially to the health care system. These and other impacts of engaging patients and informal caregivers, such as a positive refocusing on life and making sense of their illness, have been documented in published research from the UK.5,13,23 In order for patient engagement in research to have its desired positive impacts, our findings suggest that research teams should address key factors around how PRPs want to be engaged. One participant offered fundamental advice to researchers on how to engage PRPs: ‘Sit them down and ask them how they want to be engaged…Don’t assume – just ask!’ (P18). We did just that, and we offer in this paper the collective perspectives of PRPs on how they can be meaningfully engaged, which complements over a decade of literature on the subject of public and patient involvement in research.

This study is limited to the perspectives of 19 PRPs. We extended our recruitment timeline and offered an honorarium to increase the number of participants but were unable to do so within our time frame. Our sample was relatively diverse, with almost 50% male participants, three different race/ethnicity categories and a wide age spread. The option to participate by webinar broadened our sample frame to remote and rural areas of Canada, but lack of a computer and internet may have excluded the participation of under-resourced individuals.

Patient–research partnerships are mandated for research projects financed by major funding agencies in Canada, and many researchers are interested in engaging with patients.10,22 Despite this momentum, the experience of many of the participants in our study seems to suggest that improvement is needed regarding the quality of these partnerships. We recognize the evolving nature of this practice and offer recommendations from the perspectives of PRPs.

Conclusions

Our findings offer insight into the experiences of PRPs in Canada, and their recommendations suggest that research leaders should provide a welcoming research environment, outline appropriate expectations for PRPs, support PRPs in their role and facilitate and recognize the added value of PRPs’ contributions. This would improve the quality of patient–researcher partnerships and address factors contributing to PRPs’ meaningful engagement, allowing patient perspectives to be more fully integrated in the research process.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support of Leanne Heppell and Candy Garossino at Providence Health Care, and we thank the 19 individuals who shared their experiences with us.

Appendix 1

Focus group and interview questions

Patient family partner focus groups and interviews on research involvement

Health care organizations and health care funding agencies are interested in how to involve Patient Family Partners (PFPs) on research teams – as advisors, team members and as members of teams determining research priorities. PFPs are people with experience in the health care system as patients, families or informal caregivers. This interview will explore your experience with research teams. The information we learn from you will be reviewed and a report will be written with recommendations for health care leaders and researchers. This report will hopefully increase inclusion of PFPs on research teams.

Role & preparation:

Describe your role as a PFP involved in research.

What preparation was provided for the role?

What kind of preparation or training would you like to have received for your role?

Logistics and support:

How did you find out about the opportunity to participate?

How were you supported in your role on the research team?

What more can research leaders, researchers and health care organizations do to more effectively include Patient Family Partners on research teams – as advisors, team members and as members of teams determining research priorities?

Challenges and benefits and drawbacks:

What challenges did you encounter as a PFP on a research team?

During your involvement, what areas were unclear as to your role or contribution?

What benefits or drawbacks were there to participating on a research team?

Hopes for participation/what could have been done differently:

What did you hope to get out of the opportunity? Why did you sign up to participate?

What do you wish could have been done differently to make your experience more effective?

What do you wish you could tell members of your research team to improve the experience?

Impact:

How did you feel about the impact of your involvement in research?

Closing thoughts:

Anything else you’d like to share?

Appendix 2

| Quotations from participants | |

|---|---|

Research environment

|

It was just a warm atmosphere…extremely respectful of the reps. Everybody was quiet when I was speaking…give me an opportunity to explain why I did or didn’t feel that the review, like the grant was valid…I just felt like I was an equal partner sitting at that table and it was very much a team experience. (P12)As a patient, please welcome us to our role right at the beginning of the study because you’ll turn off some of the most interested people if you don’t acknowledge their role. (P2) …there are super patients. What I mean is that there’s patients that go to every single conference, every single workshop…And that’s not always bad but…but you’re really hearing their voice like 5 times…. (P18) |

Expectations

|

The whole idea of engaging patients in health research as collaborators or as partners on research team is quite novel and once it gets to be more of the norm, people will be a little bit clearer about the roles and responsibilities. So I’m not too critical about that fact! (P7) The other thing I think is a challenge is understanding the roles that people are playing on the team because you get introduced to people, sort of……and you have no idea what they’re actually doing on the project and what their role is. So it’s very hard to understand, you know, the context for the things that they say. (P15) I mean if they come in and consult on my project and then…they send a follow-up report whatever it is, even if it’s a year later and say ‘hey, this is what ended up happening. This is what we did and this is how we used your advice’ then that really helps. (P1) |

Support

|

I think that there should be fair remuneration for the work that a person does, paid or unpaid… it doesn’t inspire people to contribute and to put in the effort, you know, if they’re not being paid for travel and for their costs at a bare minimum, let alone for time and work and effort that they’re putting into a project. (P3) I felt very unprepared. .It’s like you’re on their turf and they all know one another and you’re the stranger in the room and as friendly as they try to be, if you’re not well-prepared, you really don’t know want to open your mouth and sound stupid when you don’t know enough. (P16)…a lot of us didn’t have much experience with like the logistics of research…Getting a better understanding of how the research process works. That was really helpful and supportive. (P1)For us it was really important that they were able to provide child care because, you know, the expenses when you have a child with a medical condition or disability…you can’t get just the neighbourhood 12-year-old to come and take care of them, and so those expenses can be pretty intensive. (P10) |

Value

|

…for me the major benefits have been just that sense of reward, intrinsic reward and learning. I’m learning so much and meeting people. (P7)…I was the only one at the table who realized that some of these questions were impossible…because if you had arthritis you could not do that… Or don’t expect them to be recovered after a knee replacement after 3 months…And these kinds of things researchers don’t really know. It’s the lived experience that we bring, and that’s so valuable. (P9)Researchers, they’re very, very intelligent people but they’re not - they don’t live with these conditions that the people they are trying to study do. (P3)The reason I got into the volunteering is to make the experience better than it was for me in those early days, so that… the new families that are coming up won’t have such a broken experience. |

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Clayon Hamilton receives support from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Trainee Award in Health Services.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Baker GR, Fancott C, Judd M, et al. Expanding patient engagement in quality improvement and health system redesign: three Canadian case studies. Healthc Manage Forum 2016; 29: 176–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimmin C, Wittmeier KDM, Lavoie JG, et al. Moving towards a more inclusive patient and public involvement in health research paradigm: the incorporation of a trauma-informed intersectional analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2017; 17: 539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2014; 14: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shippee ND, Domecq Garces JP, Prutsky Lopez GJ, et al. Patient and service user engagement in research: a systematic review and synthesized framework. Health Expect 2015; 18: 1151–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crocker JC, Boylan A, Bostock J, et al. Is it worth it? Patient and public views on the impact of their involvement in health research and its assessment: a UK-based qualitative interview study. Health Expect 2017; 20: 519–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.INVOLVE. Briefing notes for researchers: public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research. Eastleigh: INVOLVE, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maguire K, Britten N. ‘ How can anybody be representative for those kind of people?’ Forms of patient representation in health research, and why it is always contestable. Soc Sci Med 2017; 183: 62–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gooberman-Hill R, Burston A, Clark E. Involving patients in research: considering good practice. Musculoskelet Care 2013; 11: 187–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frank L, Forsythe L, Ellis L, et al. Conceptual and practical foundations of patient engagement in research at the patient-centered outcomes research institute. Qual Life Res 2015; 14: 1033–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Strategy for patient-oriented research – patient engagement framework. Ottawa: Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gradinger F, Britten N, Wyatt K, et al. Values associated with public involvement in health and social care research: a narrative review. Health Expect 2015; 18: 661–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esmail L, Moore E, Rein A. Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: moving from theory to practice. J Comp Eff Res 2015; 4: 133–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashcroft J, Wykes T, Taylor J, et al. Impact on the individual: what do patients and carers gain, lose and expect from being involved in research? J Ment Health 2016; 25: 28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forsythe LP, Szydlowski V, Murad MH, et al. A systematic review of approaches for engaging patients for research on rare diseases. J Gen Intern Med 2014; 29: S788–S800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibson A, Welsman J, Britten N. Evaluating patient and public involvement in health research: from theoretical model to practical workshop. Health Expect 2017; 20: 826–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton CB, Hoens AM, Backman CL, et al. An empirically based conceptual framework for fostering meaningful patient engagement in research. Health Expect 2017; 20: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen S, Doyle-Thomas KAR, Beesley L, et al. How and why should we engage parents as co-researchers in health research? A scoping review of current practices. Health Expect 2017; 20: 543–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. Res Involv Engagem 2017; 358: j3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirwan JR, de Wit M, Frank L, et al. Emerging guidelines for patient engagement in research. Value Health 2017; 20: 481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Wit MP, Elberse JE, Broerse JE, et al. Do not forget the professional – the value of the FIRST model for guiding the structural involvement of patients in rheumatology research. Health Expect 2015; 18: 489–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NHS Health Research Authority. UK policy framework for health and social care research. London: NHS Health Research Authority, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.BC Support Unit. Strategy for patient-oriented research. Building momentum for patient engagement in BC research. Available from: http://bcsupportunit.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Building-Momentum-for-Patient-Engagement-in-BC-Research-May-11-2016-Final-v2.pdf (accessed 24 February 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cotterell P, Harlow G, Morris C, et al. Service user involvement in cancer care: the impact on service users. Health Expect 2011; 14: 159–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burns N, Grove SK. Understanding nursing research: building an evidence-based practice. 5th ed Maryland Heights: Elsevier Saunders, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chong E, Alayli-Goebbels A, Webel-Edgar L, et al. Advancing telephone focus groups method through the use of webinar methodological reflections on evaluating Ontario, Canada's Healthy Babies Healthy Children Program. Glob Qual Nurs Res Epub ahead of print 5 Oct 2015. DOI: 10.1177/2333393615607840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Attride-Stirling J. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual Res 2001; 1: 385–405. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson DS, Bush MT, Brandzel S, et al. The patient voice in research-evolution of a role. Res Involv Engagem 2016; 2: 6–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ives J, Damery S, Redwod S. PPI, paradoxes and Plato: who's sailing the ship? J Med Ethics 2013; 39: 181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheung PP, de Wit M, Bingham CO, 3rd, et al. Recommendations for the involvement of patient research partners (PRP) in OMERACT working groups. A report from the OMERACT 2014 Working Group on PRP. J Rheumatol 2016; 43: 187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Health research roadmap II: capturing innovation to produce better health and health care for Canadians: strategic plan 2014-15 to 2018-19. Ottawa: CIHR, 2015. [Google Scholar]