Abstract

Introduction

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), although widely used for a long time in diffuse coronary artery disease (CAD), has serious limitations associated with graft aging and its degeneration.

Aim

The relationship between saphenous vein graft (SVG) plaque morphology assessed by optical coherence tomography (OCT) and clinical findings has not been elucidated yet.

Material and methods

We compared the morphology of SVG in stenotic vs. non-stenotic lesions using OCT imaging in 29 patients hospitalized in our center within the OCTOPUS registry.

Results

Stenotic lesions were characterized by higher incidence of thin-cap fibroatheroma (TCFA) (33% vs. 0%, p = 0.0048), thrombus (28% vs. 0%, p = 0.0008), lipid-rich plaque (LRP) (75% vs. 35%, p = 0.0013) and plaque within the SVG valve (19% vs. 0%, p = 0.0114) as compared to non-stenotic lesions. Patients with intimal tearing or rupture (ITR) were older (75.8% vs. 68.9 years, p = 0.047) and had lower left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (32.0% vs. 49.7%, p = 0.001) and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (36.0 vs. 73.6 ml/min/1.73 m2, p = 0.010). Patients with calcified lesions vs. those without had lower high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (33.2 vs. 44.1 mg/dl, p = 0.018), similarly to those with ruptured plaque vs. those without (28.3 vs. 41.7 mg/dl, p = 0.047).

Conclusions

Presence of ITR was associated with advanced age, decreased LVEF and renal insufficiency. Decreased concentration of HDL was associated with higher occurrence of calcified and ruptured plaque.

Keywords: coronary artery bypass grafting, saphenous vein graft, optical coherence tomography, thin-cap fibroatheroma, coronary artery disease

Introduction

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is widely applied to treat diffuse coronary artery disease [1]. It offers a significant reduction in mortality at 5-year follow-up compared to medical treatment only (10.2% vs. 15.8%; p = 0.0001) [2]. 88–95% of arterial conduits remain patent at ten or more years after surgery; thus their utilization is a preferred clinical modality. Unfavorably, their use has serious limitations (restrictions in the use of radial artery, mammary artery harvesting may result in sternal dehiscence and/or mediastinitis), particularly in obese and diabetic patients [3–6].

In contrast, only 32–71% of saphenous vein grafts (SVG) maintain patency at ten or more years [7–12]. As the re-do CABG has two- to four-fold increased mortality, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) within the SVG and/or native vessel remains the method of choice in the treatment of these cases [13, 14]. Percutaneous coronary intervention for SVG is associated with higher incidence of periprocedural myocardial infarction [15]. There exists a paradigm that atherosclerotic plaque localized in the venous conduits consists of friable tissue being prone to release its debris and cause distal embolization during PCI [16–19].

There is a paucity of data concerning SVG plaque burden and tissue type. The majority of these observations were made before the introduction of optical coherence tomography (OCT) to the clinical setting. Hence, the question arises whether there is a significant difference between the stenotic and non-stenotic regions of the SVG as assessed by OCT imaging.

Aim

Therefore, the aim of the study was to compare the morphology of SVG in stenotic vs. non-stenotic lesions imaged by OCT, and to present these differences in relation to clinical settings.

Material and methods

Twenty-nine patients hospitalized in the Upper Silesia Medical Center between June 2013 and March 2016 were included in the OCTOPUS registry [20, 21]. Each patient gave informed written content, and the study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was accepted by the local ethical committee.

Inclusion criteria were: CABG prior to intervention and coronary artery disease with evidence of active ischemia in non-invasive testing or acute coronary disease. Exclusion criteria were: lack of consent or less than 18 years of age or severe valvular insufficiency or contrast allergy or localization of the lesion preventing safe examination or ST-elevated myocardial infarction.

Optical coherence tomography imaging technique

The lesion was defined as stenotic when it caused 50% stenosis as assessed. Otherwise, it was recognized as non-stenotic. The non-stenotic segments of the vessel were assigned for further analysis. The St Jude Ilumien Optis Medical system was used for OCT Imaging. The OCT Dragonfly catheter was advanced through a guiding catheter over a 0.014’ guidewire into the SVG via the 6 Fr left radial or femoral approach. The OCT probe was positioned 5 mm distal to the region submitted to analysis. All OCT images were acquired using automatic pullback triggered by the hand injection of contrast flush. All patients were adequately heparinized with the activated clotting time > 300 s.

Optical coherence tomography image analysis

The OCT image analysis was performed by an independent core laboratory at Krakow Cardiovascular Research Institute (www.KCRI.org). In the case of a conflict of opinions the analyzed frame was excluded from the analysis. The OCT region of interest (ROI) was defined as the lesion length limited by areas without atheroma or neointimal hyperplasia. The OCT analysis scrutinized serial cross-sectional images of the vessel at 1 mm intervals for both stenotic and non-stenotic de novo SVG lesions. Cross-sectional area (CSA), and vessel lumen diameter were measured every 1 mm. The smallest values for both parameters were defined as the minimal lumen diameter (MLD) of the minimal CSA and were assessed for both types of lesions.

The OCT reference lumen area and reference diameter were estimated at the site of the largest CSA within the analyzed SVG for both de novo SVG lesions and non-stenotic lesions. Percentage lumen diameter and area stenosis were defined as the relative decrease in luminal diameter and CSA of the target lesion compared to the reference lumen diameter and CSA.

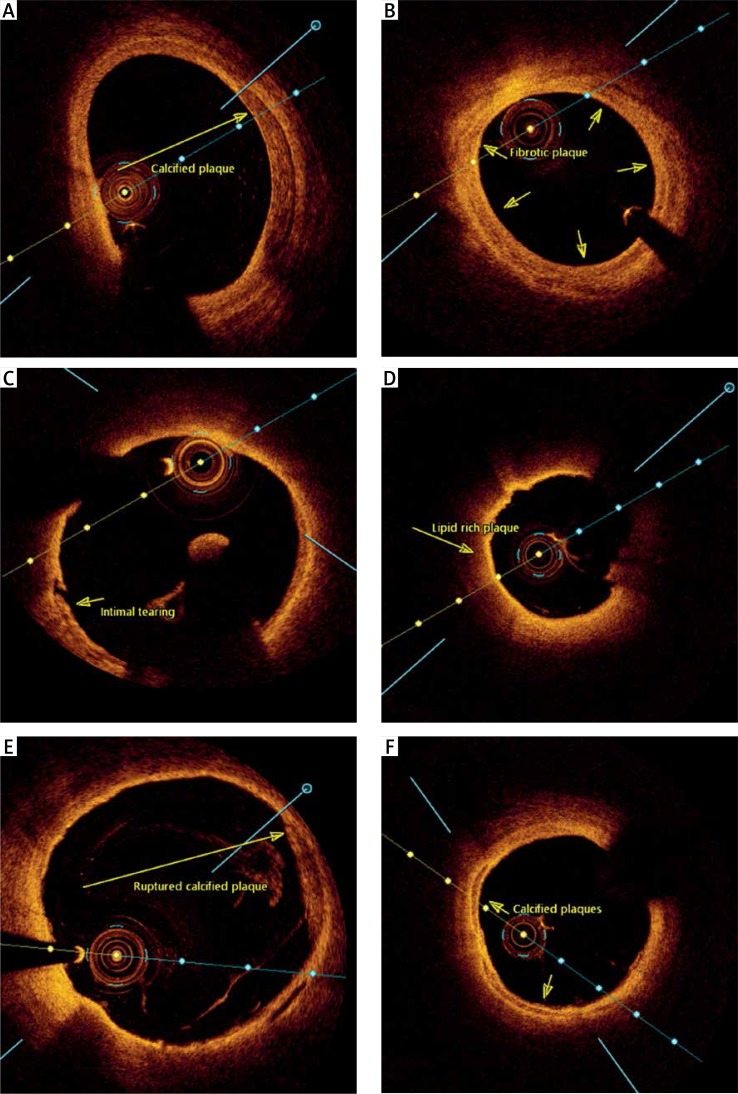

Tissue was classified as homogeneous for signal-rich regions, lipid for signal-poor regions with diffuse borders and high signal attenuation, calcified for signal-poor regions with sharp edges, and heterogeneous for poor signal regions without signal attenuation. The length of an arc of lipid and calcium that occupied the vessel wall circumference was measured and expressed in degrees [22, 23]. The maximal lipid arc and calcium arc were measured. The thickness of the fibrous cap that covered the lipid core was measured in the thinnest part of a signal-rich zone that separated the lipid content from the vessel lumen (μm). The fibrous cap thickness was the mean value of three measurements. OCT defined thin-cap fibroatheroma (TCFA) as a lipid-rich plaque (LRP) with fibrous cap thickness < 65 μm. Also, the presence of plaque rupture (PRT), luminal thrombus, intimal tear or rupture (ITR), tissue friability (FRB) and venous valves was noted during the OCT analysis. An intimal tear was defined as a micro-cavity between the SVG lumen and its media, intimal rupture as a micro-cavity of the intima connected with the SVG lumen, tissue friability as a signal-free zone overlaid with signal-rich tissue inside the SVG wall [24]. Offline OCT image analysis was performed using CAAS Intravascular 2.0 (Pie Medical Imaging BV), and results of intraobserver variability for standard protocols were presented previously [25]. See Figure 1 for different types of plaque morphologies.

Figure 1.

Different types of plaque morphologies. A–F – show different types of plaque morphologies: A – calcified plaque, B – fibrotic plaque, C – intimal tearing, D – lipid-rich plaque, E – ruptured calcified plaque, F – calcified plaques

Statistical analysis

Distributions of the examined parameters were analyzed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical variables were expressed as n and percentage. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or as the median and the 25th and 75th percentiles (interquartile range). Linear variables with normal distribution were compared using Student’s t-test. Variables with abnormal distribution were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables of abnormal distribution were compared using the χ2 test with Yates’ correction. Differences between the values were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using Statistica 10 with the medical package (StatSoft Inc.).

Results

Patients’ characteristics

Twenty-nine patients with 32 de novo SVG stenotic and 43 non-stenotic lesions were included in the study. The data for clinical characteristics were depicted on a per patient basis, and the data for plaque morphology were analyzed on a per lesion basis. Percutaneous coronary intervention was performed in 22 of the de novo SVG lesions. The study population consisted of 24 males, mean age 69.07 ±7.56. Mean duration from CABG to the index procedure was 143 (100–212) months. Eighteen (62%) patients presented with stable CAD and 11 (38%) with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Among ACS patients 10 presented unstable angina symptoms and 1 suffered from non-ST segment elevated myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). For patients’ characteristics consisting of clinical data, pharmacological therapy and laboratory findings, see Table I.

Table I.

Patient characteristics (n = 29)

| Clinical data | Value |

|---|---|

| Age ± SD | 69.07 ±7.56 |

| Male, n (%) | 24 (83) |

| Body mass index, median (IQR) [kg/m2] | 28.5 (26–32) |

| Non-ST elevated myocardial infarction, n (%) | 1 (3) |

| Unstable angina, n (%) | 10 (35) |

| Stable angina, n (%) | 18 (62) |

| Risk factors, n (%): | |

| Hypertension | 26 (90) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 25 (86) |

| Diabetes | 13 (45) |

| Current smoking | 2 (7) |

| Time from CABG, median (IQR) [months] | 143 (100–212) |

| Number of vein conduits, n (%): | |

| 1 | 4 (14) |

| 2 | 18 (62) |

| 3 | 7 (24) |

| Arterial conduit (LIMA-LAD) , n (%) | 26 (90) |

| Pharmacological therapy, n (%): | |

| Aspirin | 28 (97) |

| Thienopyridine | 2 (7) |

| β-Adrenergic antagonist | 25 (86) |

| Calcium channel antagonist | 4 (14) |

| ARB/ACEI | 20 (69) |

| Statin | 29 (100) |

| Other lipid-lowering therapy | 6 (21) |

| Oral antidiabetics | 5 (17) |

| Insulin | 2 (7) |

| Laboratory results: | |

| Hemoglobin, median (IQR) [mg/dl] | 14.08 (12.90–15.22) |

| White blood cells, median (IQR) (× 103/μl) | 6.32 (5.69–7.24) |

| Platelets, median (IQR) (× 103/μl) | 184 (161–228) |

| Total cholesterol, mean ± SD [mg/dl] | 162.29 ±58.52 |

| LDL cholesterol, median (IQR) [mg/dl] | 78 (68–98) |

| HDL cholesterol, median (IQR) [mg/dl] | 41 (32–48) |

| Triglyceride, median (IQR) [mg/dl] | 132 (103–157) |

| GFR, median (IQR) [ml/min/1.73 m2] | 71 (53–88) |

SD – standard deviation, IQR – interquartile range, CABG – coronary artery bypass grafting, LIMA-LAD – left internal mammary artery to left anterior descending artery, ARB – angiotensin II receptor blocker, ACEI – angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, LDL – low-density lipoprotein, HDL – high-density lipoprotein, GFR – glomerular filtration rate.

Data derived from optical coherence tomography analysis of saphenous vein grafts

As shown in Table II, stenotic vs. non-stenotic lesions were characterized by a raised plaque burden expressed by lowered MLD (1.88 vs. 2.83 mm), increased area stenosis (61.00% vs. 15.05%), diameter stenosis (37.33% vs. 3.0%) and maximal lipid arc (269° vs. 97°); p < 0.001 for all. Furthermore, stenotic lesions had a higher incidence of TCFA (33% vs. 0%, p = 0.0048), thrombus (28% vs. 0%, p = 0.0008), LRP (75% vs. 35%, p = 0.0013), plaque within the SVG valve (19% vs. 0%, p = 0.0114) and decreased minimal cap thickness (80 vs. 139 μm, p < 0.001).

Table II.

Comparison of stenotic vs. non-stenotic lesions in saphenous vein grafts (SVG)

| Parameter | Stenotic lesions (n = 32) | Non-stenotic lesions (n = 43) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Region of interest [mm] | 12.45 ±4.99 | 10.71 ±3.85 | 0.25 |

| Reference lumen CSA [mm2] | 7.41 (IQR: 4.38–9.38) | 7.56 (IQR: 5.60–8.70) | 0.43 |

| Reference mean lumen diameter [mm] | 3.03 ±0.73 | 3.06 ±0.46 | 0.49 |

| Minimal lesion lumen CSA, median (IQR) [mm2] | 2.71 (1.34–4.19) | NA | NA |

| Minimal lumen diameter [mm] | 1.88 ±0.65 | 2.83 ±0.45 | < 0.001 |

| Area stenosis, median (IQR) (%) | 61.00 (42.72–77.63) | 15.05 (13.0–17.0) | < 0.001 |

| Diameter stenosis (%) | 37.33 ±17.25 | 3.0 ±4.82 | < 0.001 |

| Minimal cap thickness, median (IQR) [μm] | 80 (60–101) | 139 (125–155) | < 0.001 |

| Maximal lipid arc, median (IQR) [o] | 269 (163–317) | 97 (75–120) | < 0.001 |

| Maximal calcification arc [o] | 86.89 ±54.19 | 112 ±51.6 | 0.11 |

| Plaque calcification, n (%) | 14 (44) | 16 (37) | 0.74 |

| Thin-cap fibroatheroma, n (%) | 7 (33) | 0 (0) | 0.0048 |

| Thrombus, n (%) | 9 (28) | 0 (0) | 0.0008 |

| Heterogeneous tissue, n (%) | 2 (6) | 4 (9) | 0.96 |

| Plaque rupture, n (%) | 4 (12.5) | 4 (9) | 0.95 |

| Lipid-rich plaque, n (%) | 24 (75) | 15 (35) | 0.0013 |

| Dissection, n (%) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.88 |

| Intimal tearing, n (%) | 2 (6) | 2 (5) | 0.83 |

| Intimal rupture, n (%) | 2 (6) | 3 (7) | 0.73 |

| Tissue friability, n (%) | 6 (19) | 2 (5) | 0.11 |

| Plaque within the SVG valve, n (%) | 6 (19) | 0 (0) | 0.0114 |

CSA – cross sectional area, IQR – interquartile range, NA – not applicable, SVG – saphenous vein graft; insignificant p values were rounded up to two decimal places.

Patients with fibrotic (FIB) tissue were mostly men (26 vs. 9, p = 0.004) with higher body surface area (BSA) (2.0 vs. 1.9 m2, p = 0.014) and increased serum creatinine concentration (1.1 vs. 1.0 mg/dl, p = 0.028). Moreover, this group of patients was characterized by a positive lipid profile consisting of significantly decreased triglycerides (TG) (116.0 vs. 164.4 mg/dl, p = 0.013), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol (85.1 vs. 101.2, p = 0.05) and elevated high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (43.2 vs. 34.8, p = 0.06), although neither of the last two p-values reached statistical significance. Patients with fibrotic tissue were less frequently current smokers (0 vs. 25%, p = 0.029). On the other hand, patients diagnosed with LRP had higher concentration of platelets (231.9 vs. 182.3 × 103/μl, p = 0.008) and were smokers (27% vs. 0%, p = 0.020). Data are presented in Table III.

Table III.

Clinical and imaging findings depending on tissue type according to OCT imaging

| Parameter | FIB-0 (n = 16) Mean ± SD | FIB-1 (n = 27) Mean ± SD | P-value | LRP-0 (n = 28) Mean ± SD | LRP-1 (n = 15) Mean ± SD | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEM volume [mm] | 123.4 ±53.3 | 124.3 ±57.7 | 0.96 | 115.1 ±55.8 | 140.6 ±52.7 | 0.15 |

| Lumen volume [mm] | 92.9 ±40.4 | 90.9 ±44.8 | 0.71 | 85.2 ±43.2 | 103.7 ±40.5 | 0.09 |

| Min. av. lumen diameter [mm] | 3.1 ±0.6 | 3.0 ±0.4 | 0.56 | 3.0 ±0.4 | 3.1 ±0.5 | 0.40 |

| Min. lumen area [mm2] | 7.8 ±2.8 | 7.4 ±2.1 | 0.95 | 7.3 ±2.1 | 8.0 ±2.7 | 0.62 |

| Min. lumen diameter [mm] | 2.9 ±0.6 | 2.8 ±0.4 | 0.45 | 2.8 ±0.4 | 2.9 ±0.5 | 0.20 |

| Plaque volume [mm] | 30.4 ±14.2 | 33.3 ±14.5 | 0.58 | 29.8 ±14.0 | 36.8 ±14.2 | 0.13 |

| Stenosis EEM [%] | 14.5 ±2.5 | 15.4 ±2.3 | 0.26 | 15.1 ±2.3 | 15.0 ±2.7 | 0.93 |

| Stenosis length [mm] | 10.5 ±3.9 | 10.8 ±3.9 | 0.76 | 10.1 ±3.6 | 11.8 ±4.1 | 0.17 |

| Stenosis reference (%) | 3.1 ±6.5 | 2.9 ±3.6 | 0.19 | 2.3 ±3.6 | 4.3 ±6.5 | 0.42 |

| Total lumen perimeter [mm2] | 109.8 ±41.1 | 111.5 ±43.8 | 0.90 | 103.6 ±41.6 | 124.5 ±41.6 | 0.13 |

| Age [years] | 70.4 ±5.5 | 69.3 ±8.4 | 0.65 | 68.7 ±6.4 | 71.5 ±8.7 | 0.25 |

| Body surface area [m2] | 1.9 ±0.2 | 2.0 ±0.1 | 0.014 | 2.0 ±0.2 | 2.0 ±0.2 | 0.68 |

| Body mass index [kg/m2] | 28.0 ±2.8 | 29.6 ±3.4 | 0.16 | 28.9 ±3.8 | 29.0 ±2.3 | 0.98 |

| LVEF (%) | 49.9 ±8.9 | 46.3 ±11.6 | 0.36 | 46.7 ±11.5 | 49.3 ±9.2 | 0.64 |

| Troponin before [ng/l] | 0.4 ±0.5 | 0.2 ±0.4 | 0.22 | 0.2 ±0.4 | 0.4 ±0.5 | 0.29 |

| Troponin after [ng/l] | 0.4 ±0.5 | 0.2 ±0.4 | 0.22 | 0.2 ±0.4 | 0.4 ±0.5 | 0.29 |

| HGB [mg/dl] | 15.0 ±7.3 | 15.9 ±7.1 | 0.71 | 15.9 ±7.1 | 15.0 ±7.1 | 0.69 |

| WBC [× 103/μl] | 7.1 ±1.8 | 6.9 ±1.6 | 0.54 | 6.9 ±1.4 | 7.1 ±2.0 | 0.97 |

| PLT [× 103/μl] | 221.1 ±65.8 | 189.7 ±40.9 | 0.19 | 182.3 ±31.9 | 231.9 ±65.5 | 0.008 |

| TCH [mg/dl] | 168.6 ±44.4 | 143.3 ±52.2 | 0.08 | 147.7 ±52.2 | 160.4 ±47.9 | 0.76 |

| TG [mg/dl] | 164.4 ±33.1 | 116.0 ±61.0 | 0.013 | 134.8 ±60.4 | 131.2 ±53.3 | 0.86 |

| LDL [mg/dl] | 101.2 ±37.2 | 85.1 ±34.3 | 0.05 | 88.7 ±33.0 | 94.5 ±41.3 | 0.67 |

| HDL [mg/dl] | 34.8 ±9.1 | 43.2 ±14.7 | 0.06 | 40.5 ±14.7 | 39.8 ±11.5 | 0.81 |

| Creatinine [mg/dl] | 1.0 ±0.4 | 1.1 ±0.4 | 0.028 | 1.1 ±0.3 | 1.0 ±0.3 | 0.13 |

| GFR [ml/min/1.73 m2] | 72.4 ±17.9 | 67.3 ±24.7 | 0.77 | 66.8 ±24.6 | 72.9 ±18.7 | 0.50 |

| Male, n (%) | 9 (56) | 26 (96) | 0.004 | 25 (89) | 10 (67) | 0.16 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 10 (63) | 12 (44) | 0.41 | 14 (50) | 8 (53) | 0.91 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 16 (100) | 21 (78) | 0.12 | 22 (79) | 15 (100) | 0.14 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 4 (25) | 0 (0) | 0.029 | 0 (0) | 4 (27) | 0.020 |

FIB-0/1 – fibrotic tissue absent/present, LRP-0/1 – lipid-rich plaque absent/present, EEM – external elastic membrane, min. – minimal, av. – average, LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction, HGB – hemoglobin, WBC – white blood cells, PLT – platelets, TG – triglyceride, TCH – total cholesterol, LDL – low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL – high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, GFR – glomerular filtration rate; insignificant p-values were rounded up to two decimal places, significant p-values were rounded up to three decimal places.

As presented in Table IV, patients with calcified lesions (CAL) had decreased HDL cholesterol (33.2 vs. 44.1 mg/dl, p = 0.018), similarly to those with ruptured plaque (PRT) (28.3 vs. 41.7 mg/dl, p = 0.047).

Table IV.

Clinical and imaging findings depending on tissue type according to OCT imaging

| Parameter | CAL-0 (n = 27) Mean ± SD | CAL-1 (n = 16) Mean ± SD | P-value | PRT-0 (n = 39) Mean ± SD | PRT-1 (n = 4) Mean ± SD | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEM volume [mm] | 126.9 ±57.5 | 119.0 ±53.4 | 0.66 | 125.7 ±57.5 | 107.2 ±28.2 | 0.53 |

| Lumen volume [mm] | 93.0 ±43.5 | 89.5 ±42.6 | 0.94 | 92.5 ±44.2 | 83.5 ±26.1 | 0.90 |

| Min. av. lumen diameter [mm] | 3.0 ±0.5 | 3.2 ±0.4 | 0.18 | 3.0 ±0.4 | 3.3 ±0.6 | 0.28 |

| Min. lumen area [mm2] | 7.3 ±2.3 | 8.1 ±2.3 | 0.30 | 7.4 ±2.2 | 8.8 ±3.2 | 0.42 |

| Min. lumen diameter [mm] | 2.8 ±0.4 | 2.9 ±0.5 | 0.30 | 2.8 ±0.4 | 3.0 ±0.7 | 0.42 |

| Plaque volume [mm] | 33.9 ±15.0 | 29.4 ±13.0 | 0.41 | 33.1 ±14.7 | 23.6 ±2.3 | 0.17 |

| Stenosis EEM [%] | 15.3 ±2.3 | 14.6 ±2.6 | 0.32 | 15.1 ±2.4 | 14.5 ±2.9 | 0.64 |

| Stenosis length [mm] | 11.3 ±3.8 | 9.7 ±3.9 | 0.18 | 11.0 ±3.9 | 7.6 ±1.0 | 0.10 |

| Stenosis reference (%) | 3.9 ±5.7 | 1.6 ±2.4 | 0.19 | 3.2 ±5.0 | 0.8 ±1.5 | 0.25 |

| Total lumen perimeter [mm2] | 114.4 ±42.0 | 104.9 ±43.5 | 0.48 | 113.1 ±43.6 | 89.1 ±15.7 | 0.28 |

| Age [years] | 68.3 ±8.6 | 71.9 ±4.1 | 0.12 | 69.1 ±7.4 | 75.8 ±2.5 | 0.08 |

| Body surface area [m2] | 2.0 ±0.2 | 2.0 ±0.2 | 0.76 | 2.0 ±0.2 | 1.9 ±0.1 | 0.20 |

| Body mass index [kg/m2] | 29.6 ±3.1 | 27.9 ±3.2 | 0.13 | 29.2 ±3.2 | 26.7 ±1.5 | 0.20 |

| LVEF (%) | 48.4 ±10.2 | 46.3 ±11.6 | 0.47 | 47.8 ±10.7 | 45.8 ±12.1 | 0.59 |

| Troponin before [ng/l] | 0.2 ±0.4 | 0.3 ±0.5 | 0.50 | 0.3 ±0.4 | 0.0 ±0.0 | 0.41 |

| Troponin after [ng/l] | 0.2 ±0.4 | 0.3 ±0.5 | 0.50 | 0.3 ±0.4 | 0.0 ±0.0 | 0.41 |

| HGB [mg/dl] | 16.6 ±8.5 | 13.5 ±1.2 | 0.18 | 15.8 ±7.4 | 13.6 ±1.1 | 0.56 |

| WBC [× 103/μl] | 6.6 ±1.2 | 7.6 ±2.2 | 0.19 | 6.9 ±1.5 | 7.5 ±2.6 | 0.88 |

| PLT [× 103/μl] | 202.4 ±42.0 | 196.6 ±69.4 | 0.13 | 198.4 ±48.1 | 218.8 ±89.7 | 0.91 |

| TCH [mg/dl] | 164.6 ±45.3 | 129.2 ±53.2 | 0.21 | 153.4 ±52.9 | 141.8 ±23.8 | 0.57 |

| TG [mg/dl] | 132.9 ±64.6 | 134.5 ±43.4 | 0.94 | 130.2 ±57.4 | 159.8 ±55.9 | 0.34 |

| LDL [mg/dl] | 94.2 ±42.2 | 84.3 ±18.4 | 0.90 | 91.8 ±37.1 | 82.3 ±21.3 | 0.86 |

| HDL [mg/dl] | 44.1 ±13.3 | 33.2 ±11.0 | 0.018 | 41.7 ±13.3 | 28.3 ±9.1 | 0.047 |

| Creatinine [mg/dl] | 1.0 ±0.3 | 1.1 ±0.4 | 0.87 | 1.0 ±0.3 | 1.2 ±0.6 | 0.89 |

| GFR [ml/min/1.73 m2] | 71.9 ±17.4 | 63.4 ±30.0 | 0.44 | 69.4 ±22.8 | 64.8 ±24.1 | 0.60 |

| Male, n (%) | 22 (81) | 13 (81) | 0.70 | 32 (82) | 3 (75) | 0.74 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 13 (48) | 9 (56) | 0.84 | 21 (54) | 1 (25) | 0.57 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 21 (78) | 16 (100) | 0.16 | 33 (85) | 4 (100) | 0.93 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 3 (11) | 1 (6) | 0.99 | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | 0.82 |

CAL-0/1 – calcified lesion absent/present, PRT-0/1 – plaque rupture absent/present, EEM – external elastic membrane, min. – minimal, av. – average, LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction, HGB – hemoglobin, WBC – white blood cells, PLT – platelets, TG – triglyceride, TCH – total cholesterol, LDL – low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL – high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, GFR – glomerular filtration rate; insignificant p-values were rounded up to two decimal places, significant p-values were rounded up to three decimal places.

Patients with intimal tearing or rupture (ITR) were older (75.8 vs. 68.9 years, p = 0.047), had significantly impaired systolic function with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (32.0% vs. 49.7%, p = 0.001), decreased GFR (36.0 vs. 73.6 ml/min/1.73 m2, p = 0.010) and total cholesterol (TCH) (93.4 vs. 161.3 mg/dl, p = 0.033). Patients with diagnosed ITR had raised cardiac troponin concentrations both before and after the procedure (0.6 vs. 0.2 ng/l, p = 0.05 for both) of borderline significance. Data are presented in Table V.

Table V.

Clinical and imaging findings depending on tissue type according to OCT imaging

| Parameter | ITR-0 (n = 38) Mean ± SD | ITR-1 (n = 5) Mean ± SD | P-value | FRB-0 (n = 41) Mean ± SD | FRB-1 (n = 2) Mean ± SD | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEM volume [mm] | 125.7 ±54.1 | 111.1 ±70.6 | 0.59 | 126.2 ±55.8 | 77.1 ±10.6 | 0.23 |

| Lumen volume [mm] | 92.9 ±42.0 | 82.5 ±52.0 | 0.52 | 93.3 ±43.1 | 59.1 ±9.8 | 0.12 |

| Min. av. lumen diameter [mm] | 3.0 ±0.5 | 3.2 ±0.2 | 0.47 | 3.1 ±0.5 | 3.0 ±0.6 | 0.74 |

| Min. lumen area [mm2] | 7.5 ±2.5 | 8.2 ±0.8 | 0.23 | 7.6 ±2.3 | 7.0 ±3.1 | 0.89 |

| Min. lumen diameter [mm] | 2.8 ±0.5 | 2.9 ±0.3 | 0.86 | 2.8 ±0.4 | 2.7 ±0.6 | 0.69 |

| Plaque volume [mm] | 32.8 ±13.9 | 28.5 ±18.8 | 0.36 | 33.0 ±14.3 | 17.9 ±0.8 | 0.12 |

| Stenosis EEM [%] | 15.1 ±2.5 | 14.4 ±1.1 | 0.53 | 15.1 ±2.4 | 13.5 ±0.7 | 0.36 |

| Stenosis length [mm] | 10.9 ±3.6 | 9.0 ±5.8 | 0.30 | 10.9 ±3.8 | 7.7 ±3.5 | 0.26 |

| Stenosis reference (%) | 3.3 ±5.0 | 0.6 ±1.3 | 0.14 | 3.0 ±4.9 | 2.5 ±3.5 | 1.00 |

| Total lumen perimeter [mm2] | 112.7 ±39.9 | 97.2 ±61.7 | 0.45 | 112.7 ±42.5 | 74.0 ±11.6 | 0.21 |

| Age [years] | 68.9 ±7.2 | 75.8 ±5.7 | 0.047 | 69.5 ±7.5 | 74.5 ±2.1 | 0.35 |

| Body surface area [m2] | 2.0 ±0.2 | 2.1 ±0.1 | 0.09 | 2.0 ±0.2 | 1.8 ±0.1 | 0.25 |

| Body mass index [kg/m2] | 29.0 ±3.4 | 28.4 ±2.2 | 0.69 | 29.0 ±3.2 | 27.5 ±3.5 | 0.52 |

| LVEF (%) | 49.7 ±9.4 | 32.0 ±6.7 | 0.001 | 47.5 ±10.7 | 50.0 ±14.1 | 0.62 |

| Troponin before [ng/l] | 0.2 ±0.4 | 0.6 ±0.5 | 0.05 | 0.2 ±0.4 | 1.0 ±0.0 | 1.00 |

| Troponin after [ng/l] | 0.2 ±0.4 | 0.6 ±0.5 | 0.05 | 0.2 ±0.4 | 1.0 ±0.0 | 1.00 |

| HGB [mg/dl] | 15.7 ±7.5 | 14.7 ±1.6 | 0.77 | 15.7 ±7.2 | 12.8 ±1.3 | 0.58 |

| WBC [× 103/μl] | 6.9 ±1.6 | 7.3 ±1.7 | 0.69 | 7.0 ±1.7 | 6.7 ±0.0 | 0.57 |

| PLT [× 103/μl] | 201.6 ±55.3 | 192.2 ±18.4 | 0.84 | 201.1 ±52.9 | 186.5 ±48.8 | 0.61 |

| TCH [mg/dl] | 161.3 ±41.6 | 93.4 ±67.4 | 0.033 | 151.2 ±51.7 | 169.0 ±8.5 | 0.27 |

| TG [mg/dl] | 140.4 ±55.2 | 90.6 ±55.5 | 0.07 | 131.6 ±58.2 | 165.5 ±21.9 | 0.42 |

| LDL [mg/dl] | 93.1 ±37.6 | 75.4 ±12.1 | 0.27 | 90.4 ±36.7 | 96.0 ±4.2 | 0.33 |

| HDL [mg/dl] | 40.5 ±13.0 | 38.8 ±18.2 | 0.76 | 40.3 ±13.8 | 40.0 ±8.5 | 0.89 |

| Creatinine [mg/dl] | 1.0 ±0.3 | 1.2 ±0.2 | 0.16 | 1.1 ±0.3 | 0.8 ±0.0 | 0.31 |

| GFR [ml/min/1.73 m2] | 73.6 ±17.4 | 36.0 ±29.8 | 0.010 | 68.9 ±23.2 | 69.0 ±4.2 | 0.64 |

| Male, n (%) | 31 (82) | 4 (80) | 0.60 | 35 (85) | 0 (0) | 0.036 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 19 (50) | 3 (60) | 0.96 | 20 (49) | 2 (100) | 0.49 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 32 (84) | 5 (100) | 0.79 | 35 (85) | 2 (100) | 0.64 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 3 (8) | 1 (20) | 0.95 | 3 (7) | 1 (50) | 0.43 |

ITR-0/1 – intimal tearing or rupture absent/present, FRB-0/1 – tissue friability absent/present, EEM – external elastic membrane, min. – minimal, av. – average, LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction, HGB – hemoglobin, WBC – white blood cells, PLT – platelets, TG – triglyceride, TCH – total cholesterol, LDL – low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL – high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, GFR – glomerular filtration rate; insignificant p-values were rounded up to two decimal places, significant p-values were rounded up to three decimal places.

Discussion

According to our best knowledge, there is a lack of systematic comparison between stenotic vs. non-stenotic lesions assessed by OCT; thus, we encountered serious difficulties in addressing the issue in the previously published papers. Our observations concerning stenotic lesions are in line with the work of Davlouros et al. [24] with the exception that the ACS in our group of patients occurred in the minority of cases (11 ACS vs. 18 patients with stable angina), hence TCFA, PRT and ITR were considerably less frequent. What might be a novelty in the current research is that only TCFA, LRP, thrombus and plaque within the valve had a higher incidence rate in stenotic lesions compared to non-stenotic ones. In contrast, presence of PRT, ITR and FRB did not differ significantly. Adlam et al. [26] evaluated sixteen SVGs in asymptomatic patients 3 years after cardiac surgery and reported that the rates of TCFA and thrombus were 37.5% and 25% respectively. These data are consistent with our results – incidence of TCFA and thrombus were 33% and 28% respectively. Considering the significant imbalance between the time from CABG in Adlam’s (3 years) and our (12 years) group of patients, it is tempting to speculate that the thrombus and TCFA formation accelerates in a non-linear way and a major impact on its occurrence is exerted by the quality of conduit tissue and periprocedural surgical conditions. Burgmaier et al. reported the relationship between plaque vulnerability and the left ventricle dilatation assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) in patients with type two diabetes [27]. We observed significant deterioration in the left ventricle (LV) systolic function in patients diagnosed with ITR (LVEF was 32.0% vs. 49.7%, p = 0.001). Moreover, this group of patients exhibited impaired renal function (GFR 36.0 vs. 73.6 ml/min/1.73 m2, p = 0.010). These data are in line with the previous results of Burgmaier et al., although some important differences should be addressed. First of all, we assessed the patients in a real-world setting; hence LVEF evaluation was performed by the use of ultrasound imaging and the penetration of HF is considerable (21% of patients with LVEF ≤ 35%). Secondly, despite the fact that patients with diabetes are prone to glucose fluctuations which are associated with vulnerable plaque formation [28], PRT prevalence in the dilated LV group of patients was higher but without statistical significance (22.7% vs. 8.5%, p = 0.083). Notably, although many efforts aiming to improve long-term efficacy of SVG have been made throughout the years, interesting theoretical assumptions have not necessarily had a positive impact on clinical practice [29]. Last but not least, to date nothing is known about the relationship between clinical characteristics and SVG plaque morphology assessed by OCT in patients previously submitted to CABG. Therefore we suggest initiating a randomized control trial of SVGs after cardiac surgery to address the issue of OCT-derived plaque morphology with respect to hypothetical clinical benefit in this therapeutically demanding group of patients.

This is a preliminary study that enrolled a relatively small number of patients. As it was performed in one center, although the researchers did not interfere with the management process, there exists a possibility of selection bias. Despite the fact that it was recently widely discussed and considered insignificant, since OCT is an invasive procedure there exists a theoretical possibility of iatrogenic damage of the vessel wall which might have influenced the results.

Conclusions

Stenotic lesions of the SVG had a higher incidence of LRP, TCFA, thrombus, and plaque within the valve compared to non-stenotic ones. Presence of ITR was associated with advanced age, deteriorated systolic function of the left ventricle and renal insufficiency. Decreased concentration of HDL was associated with higher occurrence of calcified and ruptured plaque.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by European Union structural funds (Innovative Economy Operational Program POIG.01.01.02-00-109/09-00) and statutory funds of the Medical University of Silesia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Authors/Task Force members. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on Myocardial Revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Developed with the Special Contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541–619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu278. Authors/Task Force members; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusuf S, Zucker D, Peduzzi P, et al. Effect of coronary artery bypass graft surgery on survival: overview of 10-year results from randomised trials by the coronary artery bypass graft surgery Trialists Collaboration. Lancet. 1994;344:563–70. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91963-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hemo E, Mohr R, Uretzky G, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with diabetes receiving bilateral internal thoracic artery grafts. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146:586–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taggart DP, Lees B, Gray A, et al. Investigators ART. Protocol for the Arterial Revascularisation Trial (ART). A randomised trial to compare survival following bilateral vs. single internal mammary grafting in coronary revascularisation [ISRCTN46552265] Trials. 2006;7:7. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elmistekawy EM, Gawad N, Bourke M, et al. Is bilateral internal thoracic artery use safe in the elderly? J Card Surg. 2012;27:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2011.01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toumpoulis IK, Theakos N, Dunning J. Does bilateral internal thoracic artery harvest increase the risk of mediastinitis? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2007;6:787–91. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2007.164343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hattler B, Messenger JC, Shroyer AL, et al. Veterans Affairs Randomized On/Off Bypass (ROOBY) Study Group. Off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery is associated with worse arterial and saphenous vein graft patency and less effective revascularization: results from the Veterans Affairs Randomized On/Off Bypass (ROOBY) Trial. Circulation. 2012;125:2827–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.069260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexander JH, Hafley G, Harrington RA, et al. PREVENT IV Investigators. Efficacy and safety of edifoligide, an E2F transcription factor decoy, for prevention of vein graft failure following coronary artery bypass graft surgery: PREVENT IV: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:2446–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.19.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tatoulis J, Buxton BF, Fuller JA. The right internal thoracic artery: the forgotten conduit--5,766 patients and 991 angiograms. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.03.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barner HB, Bailey M, Guthrie TJ, et al. Radial artery free and T graft patency as coronary artery bypass conduit over a 15-year period. Circulation. 2012;126(11 Suppl 1):S140–4. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.081497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Achouh P, Boutekadjirt R, Toledano D, et al. Long-term (5- to 20-year) patency of the radial artery for coronary bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:73–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sabik JF, Blackstone EH, Houghtaling PL, et al. Is reoperation still a risk factor in coronary artery bypass surgery? Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:1719–27. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yap CH, Sposato L, Akowuah E, et al. Contemporary results show repeat coronary artery bypass grafting remains a risk factor for operative mortality. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:1386–91. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrison DA, Sethi G, Sacks J, et al. Investigators of the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study #385, Angina With Extremely Serious Operative Mortality Evaluation. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus repeat bypass surgery for patients with medically refractory myocardial ischemia: AWESOME randomized trial and registry experience with post-CABG patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1951–4. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02560-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coolong A, Baim DS, Kuntz RE, et al. Saphenous vein graft stenting and major adverse cardiac events: a predictive model derived from a pooled analysis of 3958 patients. Circulation. 2008;117:790–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.651232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbo KM, Dooris M, Glazier S, et al. Features and outcome of no-reflow after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:778–82. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waksman R, Douglas JS, Scott NA, et al. Distal embolization is common after directional atherectomy in coronary arteries and saphenous vein grafts. Am Heart J. 1995;129:430–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90263-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baim DS, Carrozza JP. Understanding the “no-reflow” problem. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1996;39:7–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0304(199609)39:1<7::AID-CCD2>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piana RN, Paik GY, Moscucci M, et al. Incidence and treatment of “no-reflow” after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 1994;89:2514–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.6.2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roleder T, Wanha W, Smolka G, et al. Bioresorbable vascular scaffolds in saphenous vein grafts (data from OCTOPUS Registry) Postep Kardiol Inter. 2015;11:323–6. doi: 10.5114/pwki.2015.55604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roleder T, Pociask E, Wańha W, et al. Optical coherence tomography of de novo lesions and in-stent restenosis in coronary saphenous vein grafts (OCTOPUS Study) Circ J. 2016;80:1804–11. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-16-0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yabushita H, Bouma BE, Houser SL, et al. Characterization of human atherosclerosis by optical coherence tomography. Circulation. 2002;106:1640–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000029927.92825.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JS, Afari ME, Ha J, et al. Neointimal patterns obtained by optical coherence tomography correlate with specific histological components and neointimal proliferation in a swine model of restenosis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15:292–8. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jet162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davlouros P, Damelou A, Karantalis V, et al. Evaluation of culprit saphenous vein graft lesions with optical coherence tomography in patients with acute coronary syndromes. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:683–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kochman J, Tomaniak M, Kołtowski Ł, et al. A 12-month angiographic and optical coherence tomography follow-up after bioresorbable vascular scaffold implantation in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;86:E180–9. doi: 10.1002/ccd.26006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adlam D, Antoniades C, Lee R, et al. OCT characteristics of saphenous vein graft atherosclerosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:807–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burgmaier M, Frick M, Liberman A, et al. Plaque vulnerability of coronary artery lesions is related to left ventricular dilatation as determined by optical coherence tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013;12:102. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-12-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuroda M, Shinke T, Otake H, et al. Effects of daily glucose fluctuations on the healing response to everolimus-eluting stent implantation as assessed using continuous glucose monitoring and optical coherence tomography. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:79. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0395-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Węglarz P, Krejca M, Trusz-Gluza M, et al. Neointima development in externally stented saphenous vein grafts. Adv Interv Cardiol. 2016;12:334–9. doi: 10.5114/aic.2016.63634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]