Abstract

Background: Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is an important public health challenge. In recent years, there has been a greater awareness concerning this phenomenon, its causes and consequences. Due to the relational nature of IPV, attachment theory (Bowlby, 1988) appears a useful framework to read the phenomenon and to better understand its components and its dynamics to provide more precise and tailored interventions in the future.

Purpose: To summarize our knowledge of the research concerning IPV and attachment with an aim to better design and implement future research.

Methods: Computer database researches were conducted using the following databases: Psychinfo, Psycharticle, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science, and PubMed (all years to the 01/02/2018). Search terms were compiled into two concepts for all database namely Attachment and IPV.

Results: After removing the duplicates, a total of 3,598 records was screened, resulting in the identification of 319 full-text articles to be further scrutinized. Upon closer examination, there was consensus that 113 of those studies met the study inclusion criteria. Data was organized considering specifically studies concerning (1) IPV victimization and attachment, (2) IPV perpetration and attachment (both these sections were articulated in Physical, Psychological, and Sexual IPV), and (3) New research (comprising same-sex couples, IPV and attachment in couple contexts and IPV profiles and attachment among perpetrators).

Conclusion: A number of studies failed to find significant associations between insecure attachment and IPV victimization or perpetration. Additional research is needed to provide a greater understanding of different IPV forms and to aid in the development of prevention and treatment interventions.

Keywords: attachment, intimate partner violence, systematic review, victimization, perpetration, mutual violence, homosexuality

Introduction

Rationale

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is defined by World Health Organization (WHO) as “any behavior within an intimate relationship that cause physical, physical or sexual harm to those in the relationship” (Heise et al., 1999). The term IPV comprises different forms of violence, that go from manipulation to sexual coercion, that can be divided in three main categories: physical violence, psychological violence and sexual violence.

To understand violence, due to its complexity, the ecological model was applied: IPV seems to be a result of the explosive interaction between individual, relational, community and societal factors (Garcia-Moreno et al., 2005).

Physical and mental health are affected by IPV through both direct pathways, like wounds and injuries, and indirect pathways, like chronic health problems or psychological consequences of trauma and stress (Krug et al., 2002).

Due to the relational nature of IPV, we thought that Attachment Theory can be a useful framework to read the phenomenon and to better understand its components and its dynamics to provide more precise and tailored interventions in the future. At the end of the Eighties, attachment theory has also been used to investigate the quality of adult attachment relationships (Hazan and Shaver, 1987; Mikulincer and Shaver, 2007). Individual differences in adult attachment are assessed via self-report (e.g., Brennan et al., 1998) or interview (e.g., George et al., 1985; Velotti et al., 2011; Castellano et al., 2014). In both these traditions individuals can be classified into categories—secure, insecure-dismissing, insecure-preoccupied, disorganized—corresponding to those obtained among children. Also, research suggests that adult attachment is best described by two dimensions, avoidance, and anxiety (Shaver and Mikulincer, 2002; Mikulincer and Shaver, 2007). Individuals scoring high on the avoidance dimension are characterized by feelings of fear and uneasiness regarding intimacy as well as the difficulty to accept dependency on others within an affective bond (for example discomfort when the partner becomes too intimate or dependent). High scores on the anxiety dimension appear to reflect preoccupation about the reliability of the attachment figure and the availability to face the needs of attachment (for example, one might think the partner may be interested in someone else or that he/she does not desire closeness). The combination of anxiety and avoidance leads to four prototypes (Brennan et al., 1998): the secure (low levels of avoidance and low levels of anxiety), preoccupied (low levels of avoidance, but high levels of anxiety), dismissing (which is the same as the avoidant style mentioned above, with high levels of avoidance and low levels of anxiety), and lastly, the fearful style.

Each one of these lines of research has contributed to enrich the knowledge of the mechanisms, which come into play in the formation, functioning, and evolution of couple relationships (Mikulincer and Shaver, 2007).

Concerning IPV in romantic relationships, violence has been interpreted by researchers as a dysfunctional attempt to maintain proximity to the partner, that assumes the role of an attachment figure, when attachment needs are threatened (Simpson and Rholes, 1994).

According to Shaver and Mikulincer (2011), people with anxious attachment would tend to be ambivalent toward power and domination; on one hand, in fact, they would like to have control of the relationship, but on the other they may fear to obtain it, because this could provoke the resentment of the partner, and therefore constitute a threat to the stability of the relationship. People with an avoidant attachment would instead tend toward autonomy and distance, the critical vision of others, and the perception of others as objects to be used instrumentally for the satisfaction of their needs.

The joint between insecurely attached partners is peculiar: one partner may perceive a threat when the other partner claims for autonomy, as if leaving he won't ever get back again, and he gains reassurance only maintaining proximity and control over him. In reverse, the other partner may perceive partner's need for closeness and intimacy as oppressing and threatening for its autonomy. This conflicting perspectives can easily lead to a misunderstanding that often generates violence, perpetrated by one partner or both (Hazan and Shaver, 1987).

Objectives

In the years, several reviews of different nature have been conducted to explore the relationship between the two constructs.

McClellan and Killeen (2000) produced the first narrative review exploring the use of aggression by males in couples in the light of attachment theory: the paper is focused on the evidence that adults internal working models have a consistent role in their adult relationship with intimate partners, making a parallel between infant experiences of attachment and the replications of insecure patterns in adulthood.

A review on risk and protective factors for male psychological abuse toward partners has been conducted by Schumacher et al. (2001): according to this review, adult attachment, along with other factors such as communication partners and marital adjustment, is significantly associated with psychological IPV.

A review on literature on female perpetrators of IPV has been written by Carney et al. (2007): the narrative review makes an interesting confrontation on male and female offenders and includes a summary of existing intervention programs for these women.

Finkel and Slotter (2006) have discussed a narrative review, adopting an attachment perspective to reconsider IPV as an impulsive behavior that occurs when an individual feels threatened in the relationship.

Langhinrichsen-Rohling (2010) wrote an interesting paper on controversial discussions regarding gender and IPV in US, addressing topics about subtypes of IPV, differences between male and female perpetrators and gender-related challenges concerning the phenomenon.

Ogilvie et al. (2014) wrote a meta-analysis focused on attachment and violent offending, investigating controversial results about the correlation between attachment and several typologies of criminal offending (i.e., IPV, violent offending, sexual offending, non-violent offending).

The narrative review produced by Park (2016) is a very useful dissertation about implications of attachment theory applications to IPV, focused on theory's strengths and limitation in both understanding and facing the phenomenon.

Tapp and Moore (2016) produced a very useful article on instruments to assess the risk of IPV in late adolescents and young adults. It provides a very exhaustive review on the most used measures, highlighting their characteristics and efficacy, to explore the phenomenon and detect risk potential.

In the end, Karantzas et al. (2016) provided a very complete systematic review concerning the topic of attachment style and less severe forms of sexual coercion, taking in consideration the phenomenon not only in couple setting but also related to acts perpetrated toward other people.

After exploring existing reviews discussing the relationship between IPV and attachment, we found a gap in research: no other review examined studies that explored the relationship between attachment and IPV in all its manifestations nor it adopted a systematic approach nor it considered studies conducted among male and female samples.

Therefore, this systematic review has the objective to collect and draw conclusions from all the studies available that investigated the relationship between attachment and all forms of IPV, considering researches conducted among male and female samples and not only among couples. It is crucial for both clinicians and researchers to have a clearer view of the correlations between the two constructs, with the goal to elaborate specific programs, to prevent and to intervene properly on both perpetrators and victims.

Research question

Two main research questions have led to the preparation of this review: Is attachment involved in IPV? How does attachment explain the process that leads to IPV?

Method

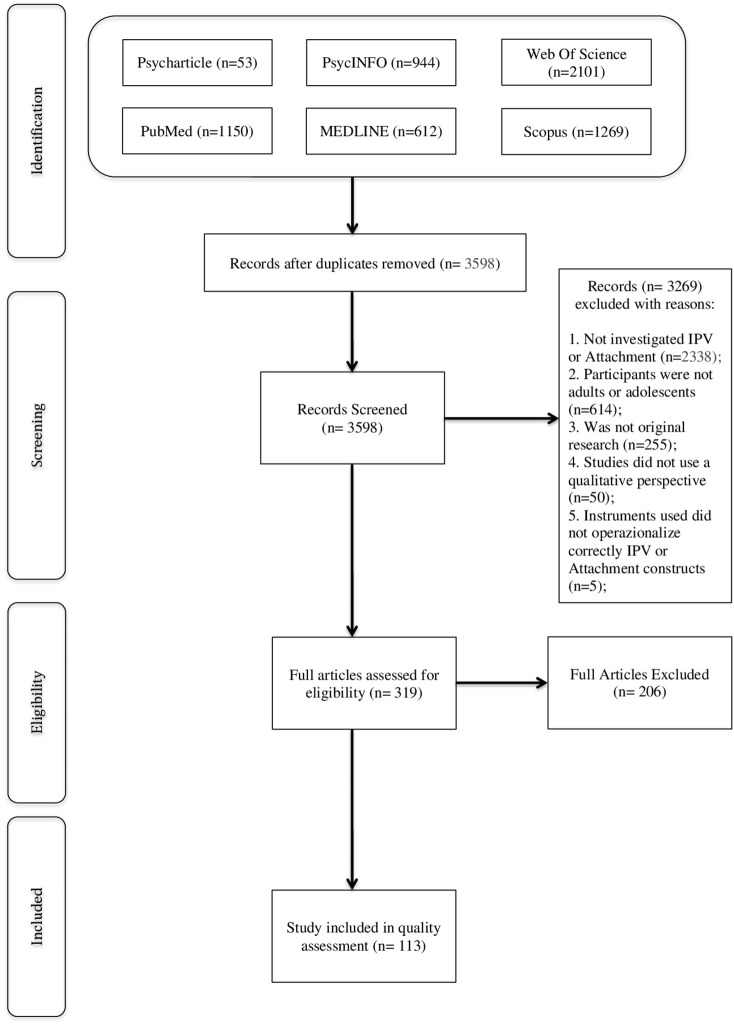

A systematic search was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). The full process of study identification, inclusion and exclusion is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram describing the processes of identification, screening and inclusion of the studies.

Search strategy

Computer database researches were conducted using the following databases: Psychinfo, Psycharticle, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science, and PubMed (all years to the 01/02/2018). Search terms were compiled into two concepts for all database namely Attachment and IPV. For Psycinfo, Psycharticle, Medline and Scopus, terms of Appendix A were searched in Title, Abstract and Key-words fields and results were refined including only articles. For Web of Science, terms presented in Appendix B were searched into Topic field. Then, we refined results including articles and excluding the Medline database. Finally, for PubMed, terms presented in Appendix B (including Mesh Terms) were searched into Title and Abstract fields.

Selection of studies

We screened every title and abstract to determine the eligibility of the study for inclusion. Criteria for inclusion of studies were the following: (1) To investigate both attachment and IPV constructs; (2) To conduct study on adults or adolescents; (3) To provide original research; (4) To use a qualitative perspective; (5) To use validated instruments for the measurement of both attachment and IPV.

Two reviewers (SBZ, GR) independently conducted the electronic searches using the aforementioned databases. Together, independent review of these electronic databases identified a total of 6,129 articles with the initial search terms, which were then examined by each reviewer for eligibility. After removing the duplicates, a total of 3,598 records was screened, resulting in the identification of 319 full-text articles to be further scrutinized. Upon closer examination, there was consensus that 113 of those studies met the study inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and reporting

A coding protocol was prepared and used to extract relevant information from the selected primary studies. In particular, six classes of information were coded: (1) characteristics of the publication (i.e., year); (2) characteristics of the sample (i.e., total sample size; gender; age was coded as the mean, standard deviation in years, sample composition); (3) information about the methodological characteristics (i.e., the context of the study was coded as the country in which the research was conducted; the type of design was coded as cross-sectional or longitudinal; the instruments used to measure attachment and IPV were reported) (4) Main results (the dimensions of attachment significantly associated with IPV were reported together with the statistical index used in the study).

Results

IPV victimization and attachment

We found 47 studies examining attachment among victims of IPV. Despite the fact that the first papers on the topic were written on 1997, 72.92% of the studies have been published in the last 10 years. Importantly, 1.46% of these studies did not distinguish between different forms of IPV. In contrast, 60.42% of the papers focused on physical IPV, 45.83% examined psychological forms of violence and only 1.25% investigated sexual IPV. Results are presented within these four categories in the following sections.

Generic IPV victimization and attachment

Table 1 displays the characteristics of the seven studies investigating attachment among victims of IPV without distinguishing between the different forms of violence. Most of researches have been conducted in USA (57.14%) and Canada (42.86%). Research is mainly cross-sectional with only two contributions adopting a longitudinal prospective (Weiss et al., 2011; La Flair et al., 2015).

Table 1.

Studies investigating the relationship between generic IPV and attachment among victims.

| References | Country | Design | Sample characteristics | Instrument used to evaluate IPV | Instrument used to evaluate attachment | Main results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender composition | Size | Type | Age | ||||||

| Wekerle and Wolfe, 1998 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Female | 193 | High school students | 15.13 (0.94) | CIRQ | ASR | Avoidance (r = 0.28) Anxiety (r = 0.19) |

| Male | 128 | 15.34 (1.75) | |||||||

| Frey et al., 2011 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 20 | Couples with men in military service | 28.50 (5.11) | IJS | MIMARA | Avoidance (r = 0.32 for F) Anxiety (r = −0.03 for F) |

| Male | 20 | 28.20 (6.24) | |||||||

| Weiss et al., 2011 | Canada | Longitudinal | Female | 90 | With intellectual disability | 15.8 (0.98) | CADRI | ASR | Security (r = −0.20) Avoidance (r = 0.33) |

| Male | 66 | ||||||||

| Shechory, 2013 | Israel | Cross-sectional | Female | 36 | With history of IPV | 35.65 (8.53) | 3 questions | ECR | Anxiety (F = 14.83; p < 0.05) Avoidance (F = 10.26; p < 0.05) |

| Female | 89 | Without history of IPV | |||||||

| Yarkovsky and Timmons Fritz, 2014 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Female | 137 | Undergraduate students | 20.76 (1.87) | CADRI | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.30) |

| La Flair et al., 2015 | USA | Longitudinal | Female | 215 | Healthcare workers | 39.7 (11.26) | AAS | ECR-R | Anxiety (r = 0.29) Avoidance (r = 0.27) |

| Lewis et al., 2017 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 293 | Couples with pregnant F with and without story of IPV | 18.7 (1.7) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (F = 5.66; p < 0.05) |

| Male | 293 | 21.3 (4.1) | |||||||

| McClure and Parmenter, 2017 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 161 | Undergraduate students | 18.83 (1.03) | CADRI | AAS (only Anxiety scale) | Anxiety (r = 0.13) |

| Male | 93 | ||||||||

IPV, Intimate Partner Violence; CIRQ, Conflict in Relationships Questionnaire; ASR, Attachment Security Ratings; IJS, Intimate Justice Scale; MIMARA, Multi Measure of Adult Romantic Attachment; F, Female; M, Male; CADRI, Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory; ECR, Experiences in Close Relationship Questionnaire; AAS, Abuse Assessment Screen; ECR-R, Experiences in Close Relationship Questionnaire Revised; CTS2, Conflict Tactics Scale Revised; AAS, Adult Attachment Scale.

Researchers generally decided to investigate the topic among samples balanced for gender with only two exceptions (Shechory, 2013; Yarkovsky and Timmons Fritz, 2014). Also, they often used participants with no previous report of IPV such as students (Wekerle and Wolfe, 1998; Yarkovsky and Timmons Fritz, 2014; McClure and Parmenter, 2017) or participants recruited among minority populations. For example, some studies have been conducted on couples with men doing military service (Frey et al., 2011), on adolescents with intellectual disability (Weiss et al., 2011) and on healthcare female workers (La Flair et al., 2015). Noteworthy, only two studies recruited participants with a previous reported history of IPV (Shechory, 2013; Lewis et al., 2017).

Also, studies showed heterogeneity regarding age of the participants with three studies investigating the topic among adult population (Frey et al., 2011; Shechory, 2013; La Flair et al., 2015), and five studies recruiting young adults or adolescents (Wekerle and Wolfe, 1998; Weiss et al., 2011; Yarkovsky and Timmons Fritz, 2014; Lewis et al., 2017; McClure and Parmenter, 2017).

Studies were highly heterogeneous regarding the instrument used to measure IPV with the most administering the Conflict in Adolescents Dating Relationships (CADRI, Wolfe et al., 2001). In contrast, measurment of attachment appeared more consistent with the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR; Brennan et al., 1998) and its revised version being the most used.

Results seem to support the hypothesis of a relationship between the attachment dimensions anxiety and avoidance and IPV victimization. Indeed, almost all correlational studies, with two exceptions (Frey et al., 2011; Weiss et al., 2011), found significant and positive correlation between the anxious dimension of attachment and IPV victimization. However, coefficient indicated only weak associations, ranging from 0.13 to 0.30. The fact that Weiss et al. (2011) did not replicate this result may be explained by the specificity of their sample, being constituted by adolescents with intellectual disability. Also, Frey et al. (2011) found a negative and significant correlation (albeit very weak: r = −0.03) between IPV victimization and anxious attachment in female partners of men doing military service. It has to be noted that the sample in this study is particularly small and results are consequently difficult to generalize to the whole population. Supporting the idea that victims of IPV may have high levels of anxious attachment, two studies successfully compared groups of females with a history of IPV with groups of females without previous reported victimization (Shechory, 2013; Lewis et al., 2017). Both found that females belonging to the IPV group scored higher on the anxious dimension of attachment compared to control participants.

Turning to the attachment dimension of avoidance, results are more contrasting with five studies showing associations with IPV victimization (Wekerle and Wolfe, 1998; Frey et al., 2011; Weiss et al., 2011; Shechory, 2013; La Flair et al., 2015) and others failing to replicate such results (Yarkovsky and Timmons Fritz, 2014; Lewis et al., 2017; McClure and Parmenter, 2017). As for the anxiety dimension, correlational coefficients indicate weak associations between avoidance and IPV victimization, ranging from 0.27 to 0.33.

Moreover, some of these studies brought additional contributions for the understanding of the relationship between IPV and attachment. For example, the role of individual differences has been pointed out, underlying that intellectual ability (Weiss et al., 2011) and gender (Wekerle and Wolfe, 1998; Lewis et al., 2017) may play a moderating role in such link. Also, two studies, using structural equation modeling, evidenced that attachment insecurity may mediate the relationship between IPV and psychological symptoms as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Frey et al., 2011) or depression (La Flair et al., 2015). Importantly, a study showed that attachment insecurity predicted no longer IPV victimization after controlling for social desirability (Yarkovsky and Timmons Fritz, 2014).

Physical IPV victimization and attachment

Studies examining attachment in victims of physical IPV were 30 (all displayed in Table 2) with 62% conducted in USA, 24.14% in Europe, 10.34% in Canada and one in Chile. Only five studies adopted a longitudinal design of research with the others being cross-sectional.

Table 2.

Studies investigating the relationship between physical IPV and attachment among victims.

| References | Country | Design | Sample characteristics | Instrument used to evaluate IPV | Instrument used to evaluate attachment | Attachment's dimensions resulting associated with IPV | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender composition | Size | Type | Age | ||||||

| Henderson et al., 1997 | Canada | Longitudinal | Female | 63 | With history of IPV | 31.4 (NA) | CTS | Interview coded with the Bartholomew's model | Fearful (r = 0.23) |

| Bookwala, 2002 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 102 | Undergraduate students | NA | CTS2 | RQ | NSO |

| Male | 59 | ||||||||

| Bond and Bond, 2004 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Female | 43 | Couples | 39.85 (10.26) | MSI-R PAPS | RQ ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.42 for F; r = −0.32 for M) Avoidance (r = 0.38 for M) |

| Male | 43 | 41.83 (11.48) | |||||||

| Henderson et al., 2005 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male and Female | 128 | Community participants | 37.4 (12.6) | CTS2 | HAI | Secure (r = −0.18) Preoccupied (r = 0.23) |

| Orcutt et al., 2005 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 457 | College students | NA | CTS2 | ECR-R | NSO |

| Rogers et al., 2005 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 80 | Couples College students | 19.54 (3.40) | HAQ | AAQ | Avoidance (Statistical index NA) |

| Male | 80 | 20.71 (3.66) | |||||||

| Toews et al., 2005 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 147 | Divorced mothers | 34 (NA) | CTS2 | RSQ | Insecurity (r = 0.30) |

| Shurman and Rodriguez, 2006 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 85 | Help-seeking victims of IPV | 33.89 (9.6) | ABI | ASQ | NSO |

| Higginbotham et al., 2007 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 299 | Undergraduate students | NA | CTS | AAQ | Insecurity (B = 0.09) |

| Rapoza and Baker, 2008 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 171 | Couples | 19.77 (3.06) | CTS2 | Questionnaire created for the study | NSO |

| Male | 171 | ||||||||

| Weston, 2008 | USA | Longitudinal | Female | 574 | Low income community | 33.97 (7.73) | SVAWS | RQ modified version | Avoidance (r = 0.25) |

| Wigman et al., 2008 | UK | Cross-sectional | Female | 127 | Undergraduate students | 21 (6.41) | CTS | RQ | Security (r = −0.16) |

| Male | 50 | 25 (8.84) | |||||||

| Scott and Babcock, 2009 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 138 | In violent relationship | 29.74 (9.34) | CTS2 | AAS | Anxiety (F = 19.85; p < 0.001) |

| Female | 37 | In non-violent relationship | 31.51 (10.17) | ||||||

| Kuijpers et al., 2012 | The Netherlands | Longitudinal | Female | 74 | Help-seeking victims of IPV | 39.28 (10.04) | CTS2 | ECR-S | Avoidance (r = 0.43) |

| Gay et al., 2013 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 396 | College students | 19.14 (1.4) | CTS2 | RSQ | Anxiety (r = 0.14) Avoidance (r = 0.10) |

| Karakurt et al., 2013 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 87 | Couples | 22.3 (4.80) | CTS | ECR | Insecurity (r = 0.39 for M) |

| Male | 87 | ||||||||

| Owens et al., 2014 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 133 | Veterans with PTSD | 51.28 (12.05) | CTS | ECR-S | Anxiety (r = 0.19) |

| Craparo et al., 2014 | Italy | Cross-sectional | Female | 80 | Victims of IPV | 31.62 (9.81) | None | ASQ | Confidence (F = 11.82; p < 0.05) Discomfort (F = 20.16 p < 0.05) Need for Approval (F = 4.97; p < 0.05) Preoccupation (F = 10.57; p < 0.05) |

| Female | 80 | Not victims of IPV | 25.05 (3.67) | ||||||

| Oka et al., 2014 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 644 | Couples | 30.25 (9.79) | 3 items of the CTS2 | BARE | Insecure (b = 0.16) |

| Male | 644 | 32.44 (10.5) | |||||||

| Hellemans et al., 2015 | Belgium | Cross-sectional | Female | 392 | Turkish minority in Belgium | 34.32 (10.74) | 7 items adopted from the WHO'study | ECR-S | Avoidance (r = 0.25) |

| Bélanger et al., 2015 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 23 | Help-seeking abusive men | 34.3 (NA) | CTS2 | ECR-S | Avoidant (r = 0.53) |

| Karakoç et al., 2015 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | Female | 36 | Depressive patients | 39.10 (10.2) | Questionnaire created for the study | ASQ | Anxiety (t = 3.9; p < 0.05) Avoidance (t = 2.8; p < 0.05) |

| 64 | Depressive patients with history of IPV | ||||||||

| Seiffge-Krenke and Burk, 2015 | Germany | Cross-sectional | Female | 194 | Couples | 16.99 (1.26) | CADRQ | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.21 for M; r = 0.27 for F) |

| Male | 194 | 18.41 (2.02) | |||||||

| Smith and Stover, 2016 | USA | Longitudinal | Female | 93 | With history of IPV | 30 (NA) | CTS2 | ECR-R | Anxiety (r = 0.32) |

| González et al., 2016 | Chile | Cross-sectional | Female | 407 | University students | 21.36 (4.48) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (statistical index NA) |

| Male | 334 | 21.38 (2.18) | |||||||

| Sandberg et al., 2016 | USA | Longitudinal | Female | 133 | College students | 22.10 (6.38) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.23) |

| Bonache et al., 2017 | Spain | Cross-sectional | Female | 638 | Students | 15.41 (1.11) | CTS | ECR-R | Avoidance (r = 0.19) |

| Male | 660 | ||||||||

| Smagur et al., 2018 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 206 | Pregnant women with an history of IPV | 25.38 (5.00) | SVAWS | ASQ | Anxiety (r = 0.21) Avoidance (r = 0.37) |

| Sommer et al., 2017 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 163 | Couples | 30.29 (9.61) | CTS2 | AAS | Anxiety (r = 0.17 for F; r = 0.23 for M) Avoidance (r = 0.23 for F; r = 0.31 for M) |

| Male | 163 | 31.90 (9.51) | |||||||

IPV, Intimate Partner Violence; NA, Not Available; CTS2, Conflict Tactics Scale Revised; RQ, Relationship Questionnaire; NSO, No Significant Outcome; MSI-R, Marital Satisfaction Inventory revised; F, Female; M, Male; PAPS, Physical Abuse of Partner Scale; HAI, History of Attachment Interview; ECR, The Experiences of Close Relationship Questionnaire; ECR-R, Experiences of Close Relationship Questionnaire Revised; HAQ, History of Abuse Questionnaire; AAQ, Adult Attachment Questionnaire; RSQ, Relationship Style Questionnaire; ABI, Abusive Behavior Inventory; ASQ, Attachment Style Questionnaire; SVAWS, Severity of Violence Against Women Scale; TLEQ, Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire; ECR-S, Experiences in Close Relationships Questionnaire Short Form; AAS, Adult Attachment Scale; BARE, Brief Accessibility, Responsiveness and Engagement Scale; CADRQ, Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Questionnaire.

Eight studies were conducted on women with a previous reported history of IPV whereas more than a third of the studies used students as participants. Seven studies were conducted on couples whereas 15 groups of researchers focused exclusively on female population. Interestingly, two studies examined the topic among clinical population suffering from PTSD and depression.

The Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS, Straus, 1979) and its revised version (CTS2, Straus et al., 1996) were the most used instrument for the assessment of physical IPV (65.52% of the studies). Instruments measuring attachment were more heterogeneous with the ECR being the most used (44.83% of the studies).

Noteworthy, all studies merging the avoidance and anxiety dimensions into a unique insecure one, evidenced a positive and significant association with physical victimization (Toews et al., 2005; Higginbotham et al., 2007; Karakurt et al., 2013). Interestingly, whereas these first evidences were brought by two studies focusing exclusively on females, Karakurt et al. (2013) successively found that such association was significant only among male participants.

Considering the specific dimensions of attachment, only four studies failed to find some kind of relationship with physical IPV victimization (Bookwala, 2002; Orcutt et al., 2005; Shurman and Rodriguez, 2006; Rapoza and Baker, 2008). In relation to the anxious facet of attachment, results are highly contrasting with 14 studies finding a role played by this dimension in physical IPV victimization and other 10 failing to replicate such result. Correlational studies providing support to the hypothesis of a relationship between physical IPV victimization and attachment reported coefficients ranging from 0.14 to 0.42. Also, studies conducted on clinical participants suffering from PTSD or depression are in line with these results (Owens et al., 2014; Karakoç et al., 2015).

Regarding the avoidant dimension, again, studies are split in two balanced categories of results with 14 failing to find any association with physical IPV victimization and 11 pointing out a significant relationship between the two variables. However, it has to be noted that from the last category, three studies suffer from methodological concerns related to the lack of a validated measure of IPV (Craparo et al., 2014; Hellemans et al., 2015; Karakoç et al., 2015). Anyway, the intensity of the significant associations reported vary from 0.10 to 0.53 with one study not reporting any statistical index (Rogers et al., 2005). Interestingly, the strongest correlation was obtained among a sample of men being in treatment for IPV perpetration (Bélanger et al., 2015).

Some studies did not limit the investigation to the relationship between attachment and IPV victimization but add other insightful considerations. For example, several studies tested this relationship considering the role of early trauma. First, results brought by Sandberg et al. (2016) underlined that anxious attachment significantly predicted physical IPV victimization also after controlling the role of trauma. In contrast, Karakoç et al. (2015) showed that, when controlling for the effect of trauma, insecure attachment no longer predicted IPV victimization among patients suffering from depression. Also, Smith and Stover (2016) found that childhood maltreatment predicted IPV victimization only when participants scored high on the anxious dimension of attachment. However, Gay et al. (2013) showed that insecure attachment did not mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and IPV victimization. No other studies tested such mediation model. Then, insecure attachment has been showed to moderate the link between IPV victimization and PTSD symptoms (Scott and Babcock, 2009) and to mediate the relationship between physical victimization and depressive symptomatology (Smagur et al., 2018). Furthermore, others variables seem to play a role in the relationship between attachment and IPV victimization as conflict resolution strategies (Bonache et al., 2017), anger (Kuijpers et al., 2012) and religiosity (Higginbotham et al., 2007). Finally, gender differences emerged in the study of Hellemans et al. (2015) suggested that physical IPV victimization was related with attachment avoidance among women and with attachment anxiety among men.

Psychological IPV victimization and attachment

Since 1997, 23 studies investigating attachment among victims of psychological IPV have been published. Characteristics of these studies are illustrated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Studies investigating the relationship between psychological IPV and attachment among victims.

| References | Country | Design | Sample characteristics | Instrument used to evaluate IPV | Instrument used to evaluate attachment | Main results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender composition | Size | Type | Age | ||||||

| Henderson et al., 1997 | Canada | Longitudinal | Female | 63 | With history of IPV | 31.4 (NA) | CTS | Interview coded with the Bartholomew's model | NSO |

| O'Hearn and Davis, 1997 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 282 | Undergraduate students | NA | PMWI Interview | RQ Interview | For self-report: NSO For Interview: Security (r = −0.35) Preoccupied (r = 0.33) |

| Henderson et al., 2005 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male and Female | 128 | Community participants | 37.4 (12.6) | CTS2 | HAI | Preoccupied (r = 0.38) |

| Toews et al., 2005 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 147 | Divorced mothers | 34 (NA) | CTS2 | RSQ | Insecurity (r = 0.31) |

| Shurman and Rodriguez, 2006 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 85 | Help-seeking victims of IPV | 33.89 (9.6) | ABI | ASQ | NSO |

| Weston, 2008 | USA | Longitudinal | Female | 574 | Low income community | 33.97 (7.73) | SOPAS | RQ modified version | Avoidant (r = 0.37 for insecure F; r = 0.35 for secure F) |

| Wigman et al., 2008 | UK | Cross-sectional | Female | 127 | Undergraduate students | 21 (6.41) | CTS | RQ | NSO |

| Male | 50 | 25 (8.84) | |||||||

| Riggs and Kaminski, 2010 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 213 | College students | 21.9 (3.70) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.15) |

| Male | 64 | 21.4 (4.25) | |||||||

| Péloquin et al., 2011 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Female | 193 | Couples | 31 (NA) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.19 for F; r = 0.32 for M) Avoidance (r = 0.29 for F) |

| Male | 193 | ||||||||

| Kuijpers et al., 2012 | The Netherlands | Longitudinal | Female | 74 | Help-seeking victims of IPV | 39.28 (10.04) | CTS2 | ECR-S | Avoidance (r = 0.32) |

| Karakurt et al., 2013 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 87 | Couples | 22.3 (4.80) | EAQ | ECR | Insecurity (r = 0.43 for M) |

| Male | 87 | ||||||||

| Owens et al., 2014 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 133 | Veterans with PTSD | 51.28 (12.05) | CTS | ECR-S | Anxiety (r = 0.22) Avoidance (r = 0.26) |

| Oka et al., 2014 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 644 | Couples | 30.25 (9.79) | 3 items of the CTS2 | BARE | NSO |

| Male | 644 | 32.44 (10.5) | |||||||

| Hellemans et al., 2015 | Belgium | Cross-sectional | Female | 392 | Turkish minority in Belgium | 34.32 (10.74) | 7 items adopted from the WHO'study | ECR-S | Anxiety (r = 0.22) Avoidance (r = 0.37) |

| Bélanger et al., 2015 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 23 | Help-seeking abusive men | 34.3 (NA) | CTS2 | ECR-S | NSO |

| Seiffge-Krenke and Burk, 2015 | Germany | Cross-sectional | Female | 194 | Couples | 16.99 (1.26) | CADRQ | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.24 for M; r = 0.32 for F) Avoidance (r = 0.20 for M; r = 0.22 for F) |

| Male | 194 | 18.41 (2.02) | |||||||

| Tougas et al., 2016 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Female | 210 | Couples | 41 (NA) | CTS2 | ECR | NSO |

| Male | 210 | 43 (NA) | |||||||

| Bonache et al., 2016 | Spain | Cross-sectional | Female | 165 | Undergraduate students | 21.40 (3.63) | CIRS | ECR-R | Anxiety (r = 0.58) Avoidance (r = 0.50) |

| Male | 51 | ||||||||

| Goncy and van Dulmen, 2016 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 113 | Dating non married couples | 19.13 (0.80) | CADRI | ECR-R | Anxiety (r = 0.37 for F; r = 0.38 for M) Avoidance (r = 0.20 for F; r = 0.22 for M) |

| Male | 113 | 20.25 (1.80) | |||||||

| Oka et al., 2016 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 457 | Couples | 43.8 (NA) | CRAVIS | ECR | Insecurity (r = 0.53 for F, r = 0.48 for M) |

| Male | 457 | 45.6 (NA) | |||||||

| Bonache et al., 2017 | Spain | Cross-sectional | Female | 638 | Students | 15.41 (1.11) | SDPAV | ECR-R | Anxiety (r = 0.27) Avoidance (r = 0.23) |

| Male | 660 | ||||||||

| Sommer et al., 2017 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 163 | Couples | 30.29 (9.61) | CTS2 | AAS | Anxiety (r = 0.17) Avoidance (r = 0.23 for F; r = 0.31 for M) |

| Male | 163 | 31.90 (9.51) | |||||||

| Smagur et al., 2018 | USA | Longitudinal | Female | 206 | Pregnant and with history of IPV | 25.38 (5.00) | SVAWS | ASQ | Anxiety (r = 0.21) Avoidance (r = 0.37) |

IPV, Intimate partner Violence; NA, Not available; CTS, Conflict Tatics Scale; NSO, No Significant Outcome; PMWI, Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory; RQ, Relationship Questionnaire; HAI, History of Attachment Interview; ABI, Abusive Behavior Inventory; ASQ, Attachment Style Questionnaire; SOPAS, Subtle and Overt Psychological Abuse Scale; F, Female; M, Male; CTS2, Conflict Tatics Scale revised; ECR, Experiences in Close Relationship; ECR-S, Experiences in Close Relationship Short Form; EAQ, Emotional Abuse Questionnaire; CRAVIS, Couples Relational Aggression and Victimization Scale; BARE, Brief Accessibility Responsiveness and Engagement scale; CADRQ, Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Questionnaire; RSQ, Relationships Style Questionnaire; CIRS, Conflict Resolution Styles Inventory; ECR-R, Experiences in Close Relationships Revised; CADRI, Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory; SDPAV, Safe Dates-Psychological Abuse Victimization; AAS, Adult Attachment Scale; SVAWS, Severity of Violence Against Women Scale.

Among them, 54.54% were conducted in USA, 22.72% in Europe and 18.18% in Canada. Despite the fact that the very two first studies were published in 1997, 81.81% of them have been published in the last 10 years. Only 18.18% of the studies were longitudinal in their design with the others being cross-sectional. Regarding sample types, most of the researches were conducted on couples (Péloquin et al., 2011; Karakurt et al., 2013; Oka et al., 2014, 2016; Seiffge-Krenke and Burk, 2015; Goncy and van Dulmen, 2016; Tougas et al., 2016; Sommer et al., 2017). Fortunately, only five groups of researchers used student samples (O'Hearn and Davis, 1997; Wigman et al., 2008; Riggs and Kaminski, 2010; Bonache et al., 2016, 2017). Two additional studies were conducted among male-only samples being veterans suffering from PTSD (Owens et al., 2014) or batterers (Bélanger et al., 2015). Unfortunately, only a small proportion of studies recruited women reporting experiences of psychological IPV (Henderson et al., 1997; Shurman and Rodriguez, 2006; Kuijpers et al., 2012; Smagur et al., 2018). Finally, two studies examined the topic among minority populations of women (Weston, 2008; Hellemans et al., 2015). Instruments used to evaluate both IPV and attachment were homogenous with ECR being mostly used to evaluate attachment styles and the subscale of CTS used to measure the intensity of psychological IPV.

Three studies, merging the anxiety and avoidance dimensions in a unique index of insecure attachment, found that psychological IPV victimization was positively correlated with insecure attachment (Toews et al., 2005; Karakurt et al., 2013; Oka et al., 2016) with coefficient ranging from 0.31 to 0.53. Noteworthy, almost half of the studies found that psychological IPV victimization was not associated with anxious or avoidant dimensions of attachment (Henderson et al., 1997; Shurman and Rodriguez, 2006; Wigman et al., 2008; Oka et al., 2014; Bélanger et al., 2015; Tougas et al., 2016).

Regarding the anxious dimension, studies conducted on women with reported history of IPV mainly failed to find an association between anxious attachment and psychological victimization (Henderson et al., 1997; Shurman and Rodriguez, 2006; Kuijpers et al., 2012). In contrast, studies recruiting students or community participants mostly indicated a relationship between anxious attachment and IPV among victims, suggesting a potential role played by sample type (O'Hearn and Davis, 1997; Henderson et al., 2005; Riggs and Kaminski, 2010; Bonache et al., 2016, 2017). Noteworthy, such studies greatly vary in the intensity of reported association with correlational coefficients ranging from 0.15 to 0.58. Finally, whereas some studies conducted on couples reported association between psychological IPV and anxious attachment among victims (Péloquin et al., 2011; Seiffge-Krenke and Burk, 2015; Goncy and van Dulmen, 2016; Sommer et al., 2017), two others studies failed to replicate such results (Oka et al., 2014; Tougas et al., 2016). However, the study of Oka et al. (2014) may be biased by methodological issues as IPV was measured throughout only three items extracted from the Conflict Tactics Scale-Revised.

Then, from 20 studies examining the relationship between avoidant attachment and psychological IPV, only 11 found a significant association between the constructs with correlational coefficients ranging from 0.20 to 0.50. In relation to the role played by gender in such relationship, Péloquin et al. (2011) found that this association was significant only among females whereas two other studies indicated significant correlations in both gender (Seiffge-Krenke and Burk, 2015; Goncy and van Dulmen, 2016; Sommer et al., 2017).

Some studies shed light on additional interesting aspects related to the link between attachment and psychological IPV victimization. First, gender differences emerged in some studies (Péloquin et al., 2011; Hellemans et al., 2015). Also, studies showed that insecure attachment not only predicted psychological IPV victimization beyond the role of depression (Riggs and Kaminski, 2010) but also mediated such relationship (Smagur et al., 2018). Finally, the use of destructive conflict strategies has been showed to explain the pathway by which insecure attachment leads to psychological IPV victimization (Bonache et al., 2016, 2017).

Sexual IPV victimization and attachment

Only six studies investigated the relationship between sexual IPV and attachment among victims (see Table 4). Interestingly, these studies are relatively recent with the majority having been published in the last 3 years. All of them, except one (Bonache et al., 2016), were conducted in USA (Weston, 2008; Karakurt et al., 2013; Ross et al., 2016; Sommer et al., 2017; Smagur et al., 2018). Half of the studies were cross-sectional in their design with the remainders being longitudinal. Studies recruited large samples ranging from 51 to 574 participants by group (Weston, 2008; Bonache et al., 2016). Noteworthy, only one research was conducted on participants with a reported history of IPV (Smagur et al., 2018) with most of others recruiting couples extracted from general population (Karakurt et al., 2013; Sommer et al., 2017) or undergraduate students (Bonache et al., 2016; Ross et al., 2016).

Table 4.

Studies investigating the relationship between sexual IPV and attachment among victims.

| References | Country | Design | Sample Characteristics | Instrument used to evaluate IPV | Instrument used to evaluate attachment | Main results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender composition | Size | Type | Age | ||||||

| Weston, 2008 | USA | Longitudinal | Female | 574 | Low income community | 33.97 (7.73) | SVAWS | RQ | Avoidance (r = 0.22 for secure F; r = 0.14 for insecure F) |

| Karakurt et al., 2013 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 87 | Couples | 22.3 (4.80) | CTS | ECR | NSO |

| Male | 87 | ||||||||

| Bonache et al., 2016 | Spain | Cross-sectional | Female | 165 | Undergraduate students | 21.40 (3.63) | SCIRS | ECR-R | Anxiety (r = 0.53) Avoidance (r = 0.34) |

| Male | 51 | ||||||||

| Ross et al., 2016 | USA | Longitudinal | Female | 584 | Undergraduate Students | 20.43 (4.64) | SCIRS | ECR-S | Anxiety (F = 3.11, p < 0.05) |

| Male | 301 | ||||||||

| Sommer et al., 2017 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 163 | Couples | 30.29 (9.61) | CTS2 | AAS | Anxiety (r = 0.17 for F; r = 0.24 for M) Avoidance (r = 0.23 for M) |

| Male | 163 | 31.90 (9.51) | |||||||

| Smagur et al., 2018 | USA | Longitudinal | Female | 206 | Pregnant and with history of IPV | 25.38 (5.00) | SVAWS | ASQ | Anxiety (r = 0.26) Avoidance (r = 0.39) |

IPV, Intimate Partner Violence; SVAWS, Severity of Violence Against Women Scale; RQ, Relationship Questionnaire; F, Female; CTS, Conflict Tactics Scale; ECR, Experience in Close Relationship Questionnaire; NSO, No Significant Outcome; SCIRS, Sexual Coercion Victimization Scale; ECR-R, Experience in Close Relationship Questionnaire Revised; ECR-S, Experiences in Close Relationship Questionnaire Short Form; AAS, Adult Attachment Scale; M, Male; ASQ, Attachment Style Questionnaire.

Results regarding the relationship between the anxious dimension of attachment among victims of sexual IPV are contrasting. Some found that sexual IPV victimization correlated positively and significantly with anxiety (Sommer et al., 2017; Smagur et al., 2018) with coefficient reaching 0.53. Also, results of Ross et al. (2016) indicated that individuals with history of sexual IPV scored higher on the anxious dimension of the Experiences in Close Relationships-Short form (ECR-S, Wei et al., 2007) compared to participants without experiences of sexual IPV. In contrast, two studies failed to find significant association between sexual IPV victimization and anxious attachment (Weston, 2008; Karakurt et al., 2013).

In relation the attachment dimension of avoidance, data brought by correlational studies mostly indicated a positive association between anxious attachment and sexual IPV with coefficients ranging from 0.22 to 0.39. Noteworthy, one of them found that the association was significant only among men. However, two studies did not go in the same direction, finding no association between avoidance and sexual IPV victimization (Karakurt et al., 2013) or no differences on avoidance scores between individuals with and without sexual IPV victimization (Ross et al., 2016).

Finally, two studies examined other variables accounting for the relationship between attachment and sexual IPV victimization showing that such link was mediated by the use of destructive conflict resolution strategies (Bonache et al., 2016) and that insecure attachment fully mediated the pathway by which childhood maltreatment leads to sexual IPV victimization (Smagur et al., 2018).

As a whole, research examining the role of attachment in IPV victimization appears widely unbalanced in relation to the type of violence investigated, with most studies measuring physical manifestation and only few including a separate measurement of sexual victimization. Despite the fact that the majority of studies found some kind of association between insecure attachment and IPV victimization, results are highly contrasting regarding the specific dimensions of attachment.

IPV perpetration and attachment

In the present review, we found 72 studies that explored the attachment dimensions among IPV perpetrators. Contrary to the studies on IPV victimization, most of the studies focused on psychological IPV (40.74%), whereas 15.52% of the studies did not make differences between the different forms of IPV, 31.04% of the studies investigated physical IPV and on 6.79% of the studies were focused on sexual IPV. The studies we examined cover a wide range of years, comprised between 1994 and 2017, even though the majority has been published in the last 10 years.

Generic IPV perpetration and attachment

Over the years, 15 studies decided to investigate the relationship between the perpetration of violence in general, not discriminating between different forms of expression, and attachment. These studies are displayed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Studies investigating the relationship between generic IPV and attachment among perpetrators.

| References | Country | Design | Sample Characteristics | Instrument used to evaluate IPV | Instrument used to evaluate attachment | Main results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender composition | Size | Type | Age | ||||||

| Babcock et al., 2000 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 23 | Violent males | NA | CTS | AAI | Insecure attachment (khi-2; p < 0.05) |

| 13 | Non-violent males | ||||||||

| Wigman et al., 2008 | UK | Cross-sectional | Male | 50 | College students | 22 (7.39) | UPBI | RQ | Preoccupied (r = 0.16) Fearful (r = 0.18) |

| Female | 127 | ||||||||

| Carraud et al., 2008 | France | Cross-sectional | Male | 50 | Convicted for IPV | 18 (NA) | CTS2 | ECR | Preoccupied, dismissing (khi-2 p < 0.05) |

| Convicted for other crimes | |||||||||

| Grych and Kinsfogel, 2010 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 188 | High School students | 15.6 (1.1) | CIR | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.19 for M; r = 0.17 for F) |

| Female | 203 | ||||||||

| Weiss et al., 2011 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 66 | High school students with ID | 15.58 (0.98) | CADRI | Attachment Security Ratings | Avoidance (r = 0.30) |

| Female | 90 | ||||||||

| De Smet et al., 2012 | Belgium | Cross-sectional | Male | 160 | Divorced | 43.1 (9.42) | RP-PSF | ECR-S | Anxiety (khi-2 = 9.58, p < 0.01) |

| Female | 236 | ||||||||

| Gay et al., 2013 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 409 | College students | 19.14 (1.4) | CTS2 | RSQ | Anxiety (r = 0.11) |

| De Smet et al., 2013 | Belgium | Cross-sectional | Male | 46 | Former couples | 47.07 (8.3) | RP-PSF | ECR-S | Anxiety (r = 0.37 for M; r = 0.41 for F) |

| Female | 46 | 44.8 (7.88) | |||||||

| Genest and Mathieu, 2014 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 80 | Males in treatment for IPV | 34.3 (NA) | CTS2 | ECR | NSO |

| Tassy and Winstead, 2014 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 62 | College students | 19.5 (NA) | RP-PSF | ECR-S | Anxiety (r = 0.19) |

| Female | 180 | ||||||||

| Ulloa et al., 2014 | USA | Longitudinal | Male | 62 | High school students | 15.87 (1.52) | CADRI | AAS | Anxiety (r = 0.06) |

| Female | 78 | ||||||||

| Muñoz, 2015 | Chile | Cross-sectional | Male | 732 | Males in treatment for IPV | NA | CTS2 | ECR-R | Anxiety (F = 8.1, p = 0.000) |

| 100 | Non-violent males | ||||||||

| Pimentel and Santelices, 2017 | Chile | Cross-sectional | Male | 20 | Violent males | 39 (7.7) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (U = 93.5; p < 0.004) |

| 20 | Non-violent males | ||||||||

| Gonzalez-Mendez et al., 2017 | Spain | Cross-sectional | Male | 166 | High school students | 15.66 (1.23) | SD CTS-S | ECR-R | Anxiety (r = 0.31) |

| Female | 190 | ||||||||

| McClure and Parmenter, 2017 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 93 | College students | 18.83 (1.03) | CADRI | AAS | NSO |

| Female | 161 | ||||||||

| Aizpitarte et al., 2017 | Spain | Cross-sectional | Male | 197 | High school students | 18.02 (1.36) | CADRI | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.33) Avoidance (r = 0.13) |

| Female | 280 | ||||||||

NA, Not available; CTS, Conflict Tactics Scale; AAI, Adult Attachment Interview; UPBI, Unwanted Pursuit Behavior Inventory; RQ, Relationship Questionnaire; IPV, Intimate Partner Violence; CTS2, Conflict Tactics Scale-Revised; ECR, Experiences in Close Relationships Scale; CIR, Conflict in Relationships scale; CADRI, Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory; F, Female; M, Male; RP-PSF, Relational Pursuit-Pursuer Short Form; ECR-S, Experiences in Close Relationships Scale-Short form; AAS, Adult Attachment Scale; RSQ, Relationship Style Questionnaire; NSO, Non-significant outcome; ECR-R, Experiences in Close Relationships Scale-Revised; SD, Safe Dates; CTS-S, Conflict Tactics Scale-Short form.

America and Europe have been the continents in which studies were mainly conducted: most of the studies were run in USA (33.3%), followed by Spain (13.3%), Chile (13.3%), and Belgium (13.3%). There was only one studied conducted in France, one in Canada and one in UK.

Research are mainly cross-sectional in their design with only one study adopting a longitudinal design of research (Ulloa et al., 2014).

Only six studies (Babcock et al., 2000; Carraud et al., 2008; Gay et al., 2013; Genest and Mathieu, 2014; Muñoz, 2015; Pimentel and Santelices, 2017) did not investigate the topic among samples balanced for gender.

Regarding sample types, researchers often used participants with no previous report of IPV such as students (Wigman et al., 2008; Grych and Kinsfogel, 2010; Gay et al., 2013; Tassy and Winstead, 2014; Ulloa et al., 2014; Aizpitarte et al., 2017; Gonzalez-Mendez et al., 2017; McClure and Parmenter, 2017) or minority population such as divorced couples (De Smet et al., 2012, 2013) and jail population (Carraud et al., 2008). In this case, only four studies recruited participants with a previous reported history of IPV (Babcock et al., 2000; Genest and Mathieu, 2014; Muñoz, 2015; Pimentel and Santelices, 2017).

Surprisingly, most studies investigated the topic among young adult population and adolescents and only six studies recruited adult population (Babcock et al., 2000; De Smet et al., 2012, 2013; Genest and Mathieu, 2014; Muñoz, 2015; Pimentel and Santelices, 2017).

Due to the age variability of the samples, there was a relevant heterogeneity concerning the instruments used to measure IPV: CTS, both in its revised and its short version (Control Tactics Scale-Short form; CTS-S), has been the most used in adult samples, whereas CADRI was the most used with adolescents. As for attachment measures, ECR, both in its revised (Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised; ECR-R, Fraley et al., 2000) and its short version, turns out to be the most used tool (62.5%) both for adult and for adolescent population. Also, an American study conducted in 2000 used Adult Attachment Interview (AAI; George et al., 1985) on batterers.

Results of the studies supported the hypothesis of a relationship between attachment dimensions and being a perpetrator of IPV. All the studies that confronted a clinical group of violent men with a control group of non-violent men (Babcock et al., 2000; Carraud et al., 2008; Muñoz, 2015; Pimentel and Santelices, 2017) proved that violent men tend to have insecure attachment (Babcock et al., 2000), showing a higher level of anxiety in close relationships (Muñoz, 2015; Pimentel and Santelices, 2017) compared to non-violent men, even though results do not agree with each other about the prevailing attachment style of clinical groups. There has been found a prevalence of preoccupied and dismissing attachment (Carraud et al., 2008) over other attachment styles.

Most of the studies support the existence of a positive correlation between the attachment dimension of anxiety and IPV perpetration, even though coefficient did not indicate any strong association. They ranged from 0.06 to 0.33.

Both the weak correlation of 0.06 and a study that did not obtain any significant outcome (McClure and Parmenter, 2017) may be explained by the use of the Adult Attachment Scale (AAS, Hazan and Shaver, 1987), which might be not enough sensitive as a tool for this specific target group, as claimed by Tasso et al. (2012).

Concerning the attachment dimension of avoidance, only two studies found a significant correlation between IPV perpetration and avoidance (Weiss et al., 2011; Aizpitarte et al., 2017), where other studies failed to replicate the same result. Correlational coefficients range from 0.30 to 0.13: as for anxiety dimension scores indicate a weak association between the two constructs.

Physical IPV perpetration and attachment

Since 1998, the relationship between attachment and physical IPV as perpetrators has been investigated in 32 studies, illustrated in Table 6.

Table 6.

Studies investigating the relationship between physical IPV and attachment among perpetrators.

| References | Country | Design | Sample Characteristics | Instrument used to evaluate IPV | Instrument used to evaluate attachment | Main results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender composition | Size | Type | Age | ||||||

| Wekerle and Wolfe, 1998 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 128 | High school students | 15.34 (1.75) | CIR | Attachment Security Ratings | Anxiety (r = 0.15) Avoidance (r = 0.21) |

| Female | 193 | 15.13 (0.94) | |||||||

| Rankin et al., 2000 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 69 | Convicted for IPV | 31 (11) | MWA | ASQ | Avoidance (r = 0.27) |

| Follingstad et al., 2002 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 223 | College students | NA | CTS | RSQ | NSO |

| Female | 199 | ||||||||

| Kim and Zane, 2004 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 52 | Korean Americans in treatment for IPV | 40.7 (9.8) | CTS | RQ | Anxiety (r = 0.28) |

| 50 | European Americans in treatment for IPV | ||||||||

| Henderson et al., 2005 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 60 | Community | 37.4 (12.6) | CTS2 | HAI | Preoccupied (r = 0.23) |

| Female | 68 | ||||||||

| Orcutt et al., 2005 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 457 | College students | NA | CTS2 | ECR-R | Anxiety (b = 0.32) Avoidance (b = −0.11) |

| Lafontaine and Lussier, 2005 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Couples | 316 | Community | 39 (NA) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (β = .15 for F) |

| Toews et al., 2005 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 147 | Divorced mothers | 34 (NA) | CTS2 | RSQ | Insecure attachment (r = 0.25) |

| Lawson et al., 2006 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 33 | In treatment for IPV | 32.8 (8.7) | CTS | AAS | NSO |

| Mauricio et al., 2007 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 192 | Convicted for IPV | 33 (8.83) | CTS | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.24) |

| Goldenson et al., 2007 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 33 | Violent | 30.9 (7.8) | Physical violence interview | ECR-R | Anxiety (F = 8.48, p = 0.005) Avoidance (F = 10.96, p = 0.002) |

| 32 | Non-violent | 32 (9.1) | |||||||

| Lawson, 2008 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 100 | Violent | 32.2 (10.3) | CTS | AAS | Closeness (r = −0.32) |

| 35 | Non-violent | 27.1 (10) | |||||||

| Wigman et al., 2008 | UK | Cross-sectional | Male | 50 | College students | 22 (7.39) | CTS | RQ | NSO |

| Female | 127 | ||||||||

| Doumas et al., 2008 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 70 | Community couples | 28.46 (10.36) | CTS | RQ | NSO |

| Female | 70 | 27.03 (10.52) | |||||||

| Godbout et al., 2009 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 315 | Community | 29.5 (5.5) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.21) Avoidance (r = 0.15) |

| Female | 329 | 27.6 (4.3) | |||||||

| Lawson and Brossart, 2009 | USA | Longitudinal | Male | 49 | In IPV treatment | 31.73 (8.83) | CTS2 | AAS | NSO |

| Brown et al., 2010 | Australia | Cross-sectional | Male | 66 | In IPV treatment | 39.9 (NA) | ABI | SSDS | Anxiety (r = 0.27) |

| Miga et al., 2010 | USA | Longitudinal | Male | 39 | Couples | 14.28 (0.78) | CIR | ECR | NSO |

| Female | 54 | ||||||||

| Lawson and Malnar, 2011 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 100 | On probation for IPV | 32.2 (10.3) | MCTS | AAS | Avoidant (r = 0.24) |

| Fournier et al., 2011 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 55 | In treatment for relationship difficulties | 37 (12.5) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.32) |

| Karakurt et al., 2013 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 87 | Couples of college students | 22.3 (4.8) | CTS2 | ECR; RQ | NSO |

| Female | 87 | ||||||||

| Owens et al., 2014 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 133 | Veterans in treatment for PTSD | 51.28 (12.05) | CTS | ECR-S | Anxiety (r = 0.19) |

| McKeown, 2014 | UK | Cross-sectional | Female | 92 | Convicted | NA | CTS2 | ECR-R | NSO |

| Brassard et al., 2014 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 302 | In treatment for relationship difficulties | 35 (10.9) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.19) |

| Lee et al., 2014 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 89 | College students | 20.81 (1.81) | CTS2 | ECR-R | Anxiety (r = 0.34) |

| Female | 392 | ||||||||

| Belus et al., 2014 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 125 | College students | 21.25 (2.21) | CTS2 | RSQ | NSO |

| Female | 306 | 21.39 (3.6) | Fearful (r = 0.13) Secure (r = −0.12) Preoccupied (r = 0.13) | ||||||

| Burk and Seiffge-Krenke, 2015 | Germany | Cross-sectional | Male | 194 | Couples of high school students | 16.99 (1.26) | CADRI | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.37 for M; r = 0.19 for F) Avoidance (r = 0.30 for M) |

| Female | 194 | 18.41 (2.02) | |||||||

| Rodriguez et al., 2015 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 39 | College students | 22.51 (4.79) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.27) |

| Female | 222 | ||||||||

| Bélanger et al., 2015 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 20 | Couples in treatment for IPV | 34.3 (NA) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.565 for F) |

| Female | 20 | 32.2 (NA) | |||||||

| González et al., 2016 | Chile | Cross-sectional | Male | 239 | College students | 21.52 (2.15) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.14 for M; r = 0.12 for F) Avoidance (r = 0.15 for M; r = 0.12 for F) |

| Female | 369 | 21.41 (2.26) | |||||||

| Sommer et al., 2017 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 163 | Couples | 31.9 (9.51) | CTS2 | AAS | Anxiety (r = 0.1666 for M; r = 0.165 for F) Avoidance (r = 0.306 for M; r = 0.227 for F) |

| Female | 163 | 30.29 (9.61) | |||||||

| Cascardi et al., 2017 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 185 | College students | 19.5 (NA) | CADRI | RSQ | Anxiety (r = 0.16) |

| Female | 327 | ||||||||

CIR, Conflict in Relationships scale; IPV, Intimate Partner Violence; MWA, Measurement of Wife Abuse; ASQ, Attachment Style Questionnaire; NA, Not available; CTS, Conflict Tactics Scale; RSQ, Relationship Style Questionnaire; NSO, Non-significant outcome; RQ, Relationship Questionnaire; CTS2, Conflict Tactics Scale-Revised; HAI, History of Attachments Interview; ECR-R, Experiences in Close Relationships Scale-Revised; ECR, Experiences in Close Relationships Scale; F, Female; AAS, Adult Attachment Scale; ABI, Abusive Behavior Inventory; SSDS, Spouse-specific dependency scale; MCTS, Modified Conflict Tactics Scale; ECR-S, Experiences in Close Relationship-Short form; CADRI, Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory; LEQ, Love Experiences Questionnaire; M, Male.

Most of the studies have been conducted in America: in USA (62.5%) and Canada (21.87%). Only three studies have been conducted in Europe, two in UK and one in Germany. Other two studies have been conducted respectively in Chile and in Australia.

In this group of studies, the most common design is cross-sectional with only one study adopting a longitudinal design, performed in USA (Lawson and Brossart, 2009).

Among all the studies, 23 of them investigated the relationship between the two dimensions among samples balanced for gender. Only four studies had female-only samples and 11 had only male samples.

Contrary to what one might thing, only ten studies (Rankin et al., 2000; Kim and Zane, 2004; Lawson et al., 2006; Goldenson et al., 2007; Mauricio et al., 2007; Lawson, 2008; Lawson and Brossart, 2009; Brown et al., 2010; Lawson and Malnar, 2011; Bélanger et al., 2015) recruited participants that had a previous history of IPV or that are convicted or in therapy because of it. Most of the samples are made up of community population: a relevant number of researches enrolled high school or college students whereas others recruited veterans in treatment for PTSD (Owens et al., 2014), men in treatment for relationship issues (Fournier et al., 2011; Brassard et al., 2014), divorced mothers (Toews et al., 2005), and female prisoners (McKeown, 2014).

All studies, except two (Wekerle and Wolfe, 1998; Burk and Seiffge-Krenke, 2015), enrolled adults or young adults in their samples, so the age of participants is quite homogeneous.

Due to this homogeneity, we can observe quite an accordance in the choice of the physical IPV measure: most of the studies used CTS, both in its revised and its short version, whereas three studies used CADRI to assess adolescents. Concerning attachment assessment, there is much more heterogeneity with most studies making use of ECR, both in its revised and its short version.

The hypothesis of a relationship between physical IPV perpetration and attachment dimensions has been supported by the results of the studies. Compared to non-violent samples, physical IPV perpetrators show higher level of anxiety and avoidance (Goldenson et al., 2007) and a preoccupied attachment style (Henderson et al., 2005). Most of the studies supported a positive correlation between physical IPV perpetration and the attachment dimension of anxiety, even though coefficient ranged from 0.56 to 0.12, so they're not really strong.

Concerning the attachment dimension of avoidance, several studies found a positive correlation with physical IPV perpetration. Correlational coefficients range from 0.30 to 0.12, so, as for attachment anxiety, they indicate a weak correlation between the constructs.

Concerning the dimension of closeness, one study found a negative correlation (r = −0.32) with physical IPV (Lawson, 2008).

Regarding gender differences, they are consistent with the trend, showing a prevalence of anxiety and avoidance in both male and female physical IPV perpetrators (González et al., 2016; Sommer et al., 2017).

Noteworthy, eight studies didn't obtain any significant outcome. However, two of them used the AAS as attachment measure, which is claimed to be not much sensitive for such samples by Tasso et al. (2012).

Psychological IPV and attachment

There are 42 studies that investigated the relationship between attachment and psychological IPV, focusing on IPV perpetration (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Studies investigating the relationship between psychological IPV and attachment among perpetrators.

| References | Country | Design | Sample characteristics | Instrument used to evaluate IPV | Instrument used to evaluate attachment | Main results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender composition | Size | Type | Age | ||||||

| Dutton et al., 1994 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 120 | In treatment for IPV | 35 (NA) | PMWI | RSQ; RQ | Anxiety (r = 0.26) |

| 40 | Non-violent | ||||||||

| Dutton, 1995 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 140 | In treatment for IPV | 35 (NA) | PMWI | RSQ | Fearful (r = 0.53) |

| 44 | Non-violent | ||||||||

| Dutton et al., 1996 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 120 | In treatment for IPV | 35 (NA) | PMWI | RSQ | Fearful (NA) |

| 40 | Non-violent | ||||||||

| O'Hearn and Davis, 1997 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 282 | College students | 20 (NA) | Verbal abuse subscale (PMWI) | RQ | Preoccupied (r = 0.39) Fearful (r = 0.14) |

| Wekerle and Wolfe, 1998 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 128 | High school students | 15.34 (1.75) | CIR | Attachment Security Ratings | Anxiety (r = 0.17) Avoidance (r = 0.24) |

| Female | 193 | 15.13 (0.94) | |||||||

| Rankin et al., 2000 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 69 | Convicted for IPV | 31 (11) | MWA | ASQ | Avoidance (r = 0.28) |

| Davis et al., 1998 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 46 | College students | 19 (NA) | PMP | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.25) |

| Female | 123 | ||||||||

| Davis et al., 2002 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 93 | College students | 19 (NA) | PMP | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.22) |

| Female | 110 | ||||||||

| Dye and Davis, 2003 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 87 | College students | 21 (3.31) | PMWI | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.28) |

| Female | 251 | ||||||||

| Henderson et al., 2005 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 60 | Community | 37.4 (12.6) | PMWI | HAI | Preoccupied (r = 0.38) |

| Female | 68 | ||||||||

| Mahalik et al., 2005 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 143 | In treatment for IPV | 34.9 (8.99) | CBI | RQ | Fearful (r = 0.28) |

| Lafontaine and Lussier, 2005 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 316 | Couples | 39 (NA) | CTS2 | ECR | Avoidance (B = 0.12 for M) Anxiety (B = 0.2 for F) |

| Female | |||||||||

| Toews et al., 2005 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 147 | Divorced mothers | 34 (NA) | CTS2 | RSQ | Attachment insecurity (r = 0.32) |

| Mauricio et al., 2007 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 192 | In treatment for IPV | 33 (8.83) | CTS | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.50) Avoidance (r = 0.16) |

| Lawson, 2008 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 100 | Violent | 32.2 (10.3) | CTS | AAS | Closeness (r = −0.30) |

| 35 | Non-violent | 27.1 (10) | |||||||

| Wigman et al., 2008 | UK | Cross-sectional | Male | 50 | College students | 22 (7.39) | CTS | RQ | NSO |

| Female | 127 | ||||||||

| Godbout et al., 2009 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 315 | Community | 29.5 (5.5) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.21) Avoidance (r = 0.15) |

| Female | 329 | 27.6 (4.3) | |||||||

| Lawson and Brossart, 2009 | USA | Longitudinal | Male | 49 | In treatment for IPV | 31.73 (8.83) | CTS2 | AAS | NSO |

| Grych and Kinsfogel, 2010 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 188 | High School students | 15.6 (1.1) | CIR | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.21 for M; r = 0.27 for F) |

| Female | 203 | ||||||||

| Gormley and Lopez, 2010 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 61 | College students | 20 (2.26) | DS | ECR-R | Anxiety (r = 0.30 for F) Avoidance (r = 0.48 for M) |

| Female | 66 | ||||||||

| Patton et al., 2010 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 1.169 | College students | 23 (NA) | NVAWS | ECR | Anxiety (B = 0.569) |

| Female | 1.614 | ||||||||

| Brown et al., 2010 | Australia | Cross-sectional | Male | 66 | In treatment for IPV | 39.9 (NA) | ABI | SSDS | Anxiety (r = 0.39) |

| Riggs and Kaminski, 2010 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 64 | College students | 21.4 (4.25) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.160) |

| Female | 221 | 21.9 (3.7) | |||||||

| Péloquin et al., 2011 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 193 | Community couples | 31 (NA) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.245 for M; r = 0.306 for F) Avoidance (r = 0.290 for F) |

| Female | |||||||||

| Clift and Dutton, 2011 | USA | Cross-sectional | Female | 914 | College students | 20.5 (2.7) | PMI | RSQ | NSO |

| Fournier et al., 2011 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 55 | In treatment for relationship difficulties | 37 (12.5) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.37) Avoidance (r = 0.407) |

| Frey et al., 2011 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 40 | Veterans in treatment for PTSD | 28.5 (5.11) | IJS | MIMARA | Avoidance (r = 0.653 for M) |

| Lawson and Malnar, 2011 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 100 | On probation for IPV | 32.2 (10.3) | MCTS | AAS | Avoidance (r = 0.28) |

| Karakurt et al., 2013 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 87 | Couples of college students | 22.3 (4.8) | CTS2 | ECR; RQ | Attachment insecurity (r = 0.398 for M; r = 0.309 for F) |

| Female | 87 | ||||||||

| Owens et al., 2014 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 133 | Veterans in treatment for PTSD | 51.28 (12.05) | CTS | ECR-S | Anxiety (r = 0.29) Avoidance (r = 0.30) |

| McKeown, 2014 | UK | Cross-sectional | Female | 92 | Convicted | (NA) | CTS2 | ECR-R | NSO |

| Brassard et al., 2014 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 302 | In treatment for relationship difficulties | 35 (10.9) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.34) Avoidance (r = 0.15) |

| Burk and Seiffge-Krenke, 2015 | Germany | Cross-sectional | Male | 194 | High school students | 16.99 (1.26) | CADRI | LEQ | Anxiety (r = 0.35 for M; r = 0.27 for F) Avoidance (r = 0.47 for M; r = 0.19 for F) |

| Female | 194 | 18.41 (2.02) | |||||||

| Wright, 2015 | USA | Longitudinal | Male | 274 | High school students | 17.53 (0.51) | Cyber Aggression Self-Report | Attachment Self-Report | Anxiety (r = 0.33) Avoidance (r = 0.19) |

| Rodriguez et al., 2015 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 39 | College students | 22.51 (4.79) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.35) |

| Female | 222 | ||||||||

| Tougas et al., 2016 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Male | 210 | Couples | 43 (NA) | CTS2 | ECR | NSO |

| Female | 210 | 41 (NA) | |||||||

| Barbaro et al., 2016 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 258 | Community | 32.1 (8.9) | MRI-S | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.66 for M; r = 0.66 for F) Avoidance (r = 0.29 for M) |

| Sommer et al., 2017 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 163 | Couples | 31.9 (9.51) | CTS2 | AAS | Anxiety (r = 0.207 for M) Avoidance (r = 0.264 for M; r = 0.259 for F) |

| Female | 163 | 30.29 (9.61) | |||||||

| Gou and Woodin, 2017 | USA | Longitudinal | Male | 69 | Pregnant couples | 34.71 (5) | CTS2 | ECR | Anxiety (r = 0.30 for M) |

| Female | 71 | 32.24 (4.78) | |||||||

| Cascardi et al., 2017 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 185 | College students | 19.5 (NA) | CADRI | RSQ | Anxiety (r = 0.33) |

| Female | 327 | ||||||||

| Wright, 2017 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 276 | College students | 20.68 (0.61) | IPV Self-report | ECR-R | Anxiety (r = 0.36) Avoidance (r = 0.20) |

| Female | 324 | ||||||||

IPV, Intimate Partner Violence; PMWI, Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory; RSQ, Relationship Style Questionnaire; RQ, Relationship Questionnaire; NA, Not available; CIR, Conflict in Relationships scale; MWA, Measure of Wife Abuse; ASQ, Attachment Style Questionnaire; PMP, Psychological Maltreatment of Partner; ECR, Experiences in Close Relationships Scale; HAI, History of Attachments Interview; CBI, Controlling Behavior Index; M, male; F, female; CTS2, Conflict Tactics Scale - Revised; CTS, Conflict Tactics Scale; NSO, Non-significant outcome; AAS, Adult Attachment Style; MMEA, Multidimensional Measure of Emotional Abuse; ECR-R, Experiences in Close Relationships Scale-Revised; DS, Dominance Scale; NVAWS, National Violence Against Women Survey modified to assess perpetration; ABI, Abusive behavior inventory; SSDS, Spouse-specific dependency scale; PMI, gender neutral version of Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory; IJS, Intimate Justice Scale; MIMARA, Multi-Item Measure of Adult Romantic Attachment; MCTS, Modified Conflict Tactics Scale; ECR-S, Experiences in Close Relationships Scale-Short form; CADRI, Conflict in Adolescence Rating Scale; LEQ, Love Experiences Questionnaire; MRI-S: Mate Retention Inventory-Short Form.

Most of the studies have been conducted in America (64.28% in USA and 26.19% in Canada), with only two studies conducted in UK, one in Germany and one in Australia.

Studies have predominantly a cross-sectional design; only three studies present a longitudinal design (Lawson and Brossart, 2009; Wright, 2015; Gou and Woodin, 2017).

Surprisingly, only 22 studies investigated the topic among samples balanced for gender; instead, 16 studies had an exclusively male sample and 4 studies had an exclusively female sample.

Concerning sample nature, a relevant number of researches enrolled participants from community samples: most of them were conducted among high school and college students, couples and veterans in treatment for PTSD. Only 11 studies were focused on subjects with a history of IPV (Dutton et al., 1994, 1996; Dutton, 1995; Rankin et al., 2000; Mahalik et al., 2005; Mauricio et al., 2007; Lawson, 2008; Lawson and Brossart, 2009; Brown et al., 2010; Lawson and Malnar, 2011; McKeown, 2014).

Most of the studies were conducted among adult and young adult population, whereas only four studies investigated the topic among adolescents. According to the age of the samples, there was a consistent homogeneity over the instruments used to measure attachment: the most used instrument in adult sample was the ECR, both in its revised and its short version, although several studies used other measures.

Instead, concerning instruments to measure IPV, there was a remarkable variability presumably imputable to construct complexity, as psychological violence comprises very different forms of violence from verbal abuse to cyber aggression. It follows that the most used tool has been CTS, both in its revised and its short version, because of its ability to detect different types of psychological violence, less or more severe. Another common measure is the Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory (PMWI, Tolman, 1999), made up of several abuse typologies subscales. Other studies measured specific forms of violence with relevant instruments: as Controlling Behavior Index (BCI, Dobash et al., 1996), Dominance Scale (DS, Hamby, 1996), Intimate Justice Scale (IJS, Jory, 2004) and Mate Retention Inventory (MRI, Buss et al., 2008). In a longitudinal study conducted among high school students (Wright, 2015) there have been developed two specific self-report questionnaires to measure both attachment and cyber aggression.

Even though studies present a relevant heterogeneity, mainly for kind of violence and for sample composition, they supported the hypothesis of a relationship between insecure attachment and psychological IPV perpetration.

Four studies that confronted clinical groups of IPV perpetrators with control groups of non-perpetrators showed that attachment anxiety or fearful attachment make the difference between the two groups (Dutton et al., 1994, 1996; Dutton, 1995) and that IPV has a negative correlation (r = −0.30) with the attachment dimension of closeness (Lawson, 2008).

Concerning gender difference, there are contrasting results: even though most studies state that both male and female perpetrators tend to present attachment anxiety, some studies have found a prevalence of avoidant attachment in male samples compared to female (Lafontaine and Lussier, 2005; Gormley and Lopez, 2010; Frey et al., 2011; McKeown, 2014; Sommer et al., 2017).

The majority of studies support a positive correlation between psychological violence perpetration and the attachment dimension of anxiety, albeit the association indicated by coefficients ranged from 0.66 to 0.16. Regarding the association between avoidance and psychological IPV, several studies support the positive correlation between the two constructs, but the coefficient tend to be weak also in this case, ranging from 0.65 to 0.15.

Sexual IPV and attachment

As shown in Table 8, only seven studies investigated the relationship between sexual IPV and attachment from the perspective of the perpetrator.

Table 8.

Studies investigating the relationship between sexual IPV and attachment among perpetrators.

| References | Country | Design | Sample characteristics | Instrument used to evaluate IPV | Instrument used to evaluate attachment | Main results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender composition | Size | Type | Age | ||||||

| Kalichman et al., 1994 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 123 | College students | 19.6 (1.33) | CTS | Attachment Security Ratings | NSO |

| Rankin et al., 2000 | USA | Cross-sectional | Male | 69 | Convicted for IPV | 31 (11) | MWA | ASQ | Avoidance (r = 0.29) |