Abstract

Background

Vitamin D has anticarcinogenic and immune-related properties and may protect against some diseases, including breast cancer. Vitamin D affects gene transcription and may influence DNA methylation.

Methods

We studied the relationships between serum vitamin D, DNA methylation, and breast cancer using a case-cohort sample (1070 cases, 1277 in subcohort) of non-Hispanic white women. For our primary analysis, we used robust linear regression to examine the association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) and methylation within a random sample of the cohort (“subcohort”). We focused on 198 CpGs in or near seven vitamin D-related genes. For these 198 candidate CpG loci, we also examined how multiplicative interactions between methylation and 25(OH)D were associated with breast cancer risk. This was done using Cox proportional hazards models and the full case-cohort sample. We additionally conducted an exploratory epigenome-wide association study (EWAS) of the association between 25(OH)D and DNA methylation in the subcohort.

Results

Of the CpGs in vitamin D-related genes, cg21201924 (RXRA) had the lowest p value for association with 25(OH)D (p = 0.0004). Twenty-two other candidate CpGs were associated with 25(OH)D (p < 0.05; RXRA, NADSYN1/DHCR7, GC, or CYP27B1). We observed an interaction between 25(OH)D and methylation at cg21201924 in relation to breast cancer risk (ratio of hazard ratios = 1.22, 95% confidence interval 1.10–1.34; p = 7 × 10−5), indicating a larger methylation-breast cancer hazard ratio in those with high serum 25(OH)D concentrations. We also observed statistically significant (p < 0.05) interactions for six other RXRA CpGs and CpGs in CYP24A1, CYP27B1, NADSYN1/DHCR7, and VDR. In the EWAS of the subcohort, 25(OH)D was associated (q < 0.05) with methylation at cg24350360 (EPHX1; p = 3.4 × 10−8), cg06177555 (SPN; p = 9.8 × 10−8), and cg13243168 (SMARCD2; p = 2.9 × 10−7).

Conclusions

25(OH)D concentrations were associated with DNA methylation of CpGs in several vitamin D-related genes, with potential links to immune function-related genes. Methylation of CpGs in vitamin D-related genes may interact with 25(OH)D to affect the risk of breast cancer.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13058-018-0994-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Vitamin D, 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, DNA methylation, Epigenome-wide association study

Background

Vitamin D may protect against poor health outcomes, including heart disease, diabetes, certain cancers, and overall mortality [1–5]. Its biological properties include regulation of cell proliferation and immune function, as well as increased cell differentiation and apoptosis [6–10]. These mechanisms are controlled by the active metabolite 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D) and the vitamin D receptor (VDR), often in conjunction with retinoid X receptor alpha (RXRA) [11]. This 1,25(OH)2D-VDR-RXRA complex binds to vitamin D response elements that can activate or repress gene transcription [12].

Circulating vitamin D levels could affect DNA methylation via transcriptional regulation or other mechanisms [13]. In mammals, DNA methylation is an epigenetic process by which a methyl group is transferred onto the C5 position of a cytosine, forming 5-methylcytosine. Increased methylation at CpG sites in promoter regions is associated with gene inactivation and transcriptional repression, while increased methylation at CpGs in gene bodies is associated with actively transcribed genes [14, 15]. Examples of other environmental exposures associated with methylation changes include smoking (for both smokers [16] and their offspring [17–19]), as well as body mass index (BMI) [20, 21], alcohol consumption [22], and nutrients such as folate, vitamin B12, and retinoic acid [23–27].

Some empirical evidence supports a link between vitamin D exposure and DNA methylation. Candidate gene approaches have observed that vitamin D is associated with methylation of CYP24A1 [28, 29], BMP2 [30], PTEN [31], and DKK1 [32]. Additionally, one epigenome-wide association study (EWAS) conducted among adolescent African-American males identified two sites (cg16317961 (MAPRE2) and cg04623955 (DIO3)) that were significantly associated with serum levels of the stable precursor to 1,25(OH)2D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) [33]. However, those findings did not replicate in a subsequent EWAS conducted among Caucasian men, nor did that subsequent EWAS identify any novel associations [34]. Another EWAS observed no noteworthy associations between maternal 25(OH)D levels and methylation in cord blood [35], and an epigenome-wide in-vitro study identified no detectable methylation changes in blood mononuclear cells treated with vitamin D [36]. Several studies of the association between vitamin D and LINE-1 global methylation levels have also been negative [37–39].

To further investigate a possible link between vitamin D and DNA methylation, we studied the relationship between serum 25(OH)D and CpGs in or near seven vitamin D-related genes (VDR, RXRA, CYP2R1, CYP24A1, GC, CYP27B1, and DHCR7/NADSYN1) using a random sample of women from a large prospective cohort (“subcohort”). Based on our previous finding that serum 25(OH)D was associated with a 21% reduction in the hazard of breast cancer over 5 years of follow-up [3], and other research observations that methylation status can modify the responses of individuals to vitamin D treatment [28, 29], we also examined 25(OH)D-methylation interactions in relation to breast cancer risk. We additionally conducted an EWAS of serum 25(OH)D.

Methods

Study sample

The Sister Study is a prospective cohort study of 50,884 US women (2003–2009) [40]. At baseline, participants were 35–74 years old and had a sister who had been diagnosed with breast cancer but who had never had breast cancer themselves. Each completed a computer-assisted telephone interview, with in-home collection of anthropometric measurements and blood samples. Participants remain under active surveillance, with more than 90% responding to their most recent follow-up request through March 2015 (data release 4.1). When possible, we collected medical records from self-reported breast cancer cases (82%). Among those with medical records available, 99% of self-reported diagnoses were confirmed.

Participants for a DNA methylation substudy were previously sampled using a case-cohort design [41, 42]. To minimize genetic variation due to racial heterogeneity, this sample was limited to non-Hispanic white women, including all such women who had available blood samples and a self-reported diagnosis of invasive breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ. The initial methylation sample included 1542 women who developed incident breast cancer between enrollment and March 2015, and a random sample of 1336 women drawn from the full cohort, 74 of whom developed breast cancer by March 2015.

The participants for our previous analysis of serum 25(OH)D and breast cancer [3] were selected to overlap with the case-cohort sample who had DNA methylation data. However, when looking at methylation and 25(OH)D together, we excluded 429 participants who did not have 25(OH)D measured and 102 participants with quality control-related concerns with regard to their DNA methylation (described below). In the end, we had 1070 cases and 1277 in the subcohort (46 of whom were also cases) who had both DNA methylation and serum 25(OH)D data available. All women provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the institutional review boards of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the Copernicus Group.

Serum 25(OH)D assessment

Baseline serum was stored at −80 °C before being analyzed using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS) at Heartland Assays, Inc. (Ames, IA). The three 25(OH)D metabolites—25(OH)D3, 25(OH)D2, and 3-epi-25(OH)D3—were assessed individually, but we summed their concentrations to estimate total 25(OH)D. We adjusted total 25(OH)D values for batch effects using a random effects model and for season of blood draw using LOESS regression. Further details are provided elsewhere [3].

Methylation analysis

We assessed DNA methylation at 485,512 CpGs (450 K HumanMethylation Beadchip; Illumina, Inc.) using whole blood samples collected from case-cohort participants. Briefly, we extracted 1 μg genomic DNA from whole blood and conducted bisulfite-conversion using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research, Orange County, CA). Methylation analysis was carried out at the Center for Inherited Disease Research at Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). Data processing and quality control assessments were completed using the ‘ENMIX’ package (R v3.2.1) [43], and included correcting fluorescent dye-bias [44], quantile normalization [45], and reduction of background noise. We excluded 102 participants whose sample had > 5% low-quality methylation values, low average bisulfite intensity, or implausible methylation value distributions (final n = 1277 in subcohort and 1024 additional cases, as described above, plus 123 duplicate samples). We excluded CpGs if they were Illumina-designed single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) probes, on the Y chromosome, had > 5% low-quality data, were within 2 base pairs of a common SNP, or had multimodal distributions. This left us with 423,500 CpGs. For each site, we calculated a β value based on each individual’s proportion of unmethylated (U) and methylated (M) sites at a given locus: β = M/(U + M + 100).

As interperson variability can be low at some CpGs, we conducted additional screening to better ensure the reliability of our results. We calculated intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) to compare the technical variation (within-subject variability, assessed using duplicate samples) to the biologic variation (between-subject variability) [46]. We observed that, for approximately 66% of CpGs, the ICC was less than 0.5, suggesting that there is little interindividual variability and some of the corresponding observed associations may not reflect true biologic differences. We have flagged these CpGs in our results.

Candidate gene selection

Candidate genes included VDR and RXRA, as well as the vitamin D binding protein gene (GC), and genes directly involved in vitamin D metabolism (DHCR7/NADSYN1, CYP24A1, CYP27B1, and CYP2R1). We selected any CpGs included on the 450 K HumanMethylation Beadchip (Illumina, Inc.) located within 2000 base pairs from the candidate gene’s transcription start and end sites, as defined by University of California Santa Cruz Genome Browser (GRCh37/hg19; RefSeq notation) [47]. We identified 198 eligible CpGs.

Statistical analysis

25(OH)D and methylation of vitamin D-related genes in the subcohort

We assessed the relationship between serum 25(OH)D (continuous, ng/mL) and methylation (continuous, measured as the logit of β) at each of 198 CpGs in or near vitamin D-related genes using robust linear regression with M-estimation. This analysis was limited to the 1270 individuals in the subcohort who had complete information for the following covariates: age at blood draw (continuous), BMI (continuous; kg/m2), current smoking status (dichotomous), and alcohol use (never/former drinker, current drinker < 1 drink/day, or current drinker ≥ 1 drink per day). In addition to these covariates, we also adjusted for cell type proportions (CD8 T cells, CD4 T cells, natural killer cells, B cells, monocytes, or granulocytes versus other) [48].

25(OH)D-methylation interaction and breast cancer risk in the case-cohort

Next, we used the case-cohort sample to examine whether interactions between serum 25(OH)D and methylation of vitamin D-related genes were related to breast cancer incidence. This included an assessment of the relationship between methylation at each of the CpG sites in or near vitamin D-related genes and risk of breast cancer. For both sets of analyses, we used Cox proportional hazards models to account for the case-cohort design [41, 42]. We adjusted for age at blood draw, BMI, smoking status, alcohol use, and cell type proportions, as well as education, current hormone therapy use and type, current hormonal birth control use, menopausal status, usual physical activity, history of osteoporosis, parity, and a BMI-menopausal status interaction term. For these candidate CpG locus analyses, we considered p < 0.05 to be statistically significant.

For the interaction analysis, the effect measures of interest were ratios of hazard ratios (RHRs). Here, the numerator of the RHR is the hazard ratio (HR) for the association between methylation (measured as 0.1 increments of logit(β)) and breast cancer among those with 25(OH)D levels > 38.0 ng/mL, and the denominator of the RHR is the HR for the association between methylation and breast cancer among those with 25(OH)D levels ≤ 38.0 ng/mL). Therefore, RHR values > 1.00 correspond to a higher estimated HR for the methylation-breast cancer association among those with 25(OH)D levels > 38.0 ng/mL and values < 1.00 correspond to a higher estimated methylation-breast cancer HR among those with 25(OH)D levels ≤ 38.0 ng/mL. The 25(OH)D cut-point was selected based on previous evidence that 38.0 ng/mL is relevant for predicting breast cancer risk [3]. These models also included all of the baseline covariates listed above for the methylation-breast cancer association analysis.

Epigenome-wide association study of 25(OH)D in subcohort or cases

We examined the association between serum 25(OH)D and DNA methylation in the subcohort for all 423,500 CpGs from the 450 K panel that passed quality control checks. Here, we corrected for multiple comparisons by calculating false discovery rate q values [49], considering those with q < 0.05 to be likely to be true positives.

We next assessed the relationship between 25(OH)D and DNA methylation in an independent sample of participants who developed breast cancer within 5 years of enrollment, who were not part of the subcohort, and had the required covariate information (“cases”; n = 1024). Here, our goal was to identify CpGs where the 25(OH)D-methylation association differed by future breast cancer status. We compared the subcohort and case results by plotting the –log10 p values multiplied by the direction of each tested association. We then calculated critical values for a test of the combined p values based on Fisher’s method [50]. CpGs that had combined p values below identified thresholds were included in additional interaction analyses using the methods described above.

Results

Women who developed breast cancer during the 5-year follow-up period were slightly older than those in the subcohort (58.7 years versus 55.7 years) and had lower prediagnosis 25(OH)D levels (32.3 versus 32.7 ng/mL). Cases were more likely to have more than one first-degree relative with breast cancer, to be postmenopausal, to be obese, or to be currently taking hormone therapy (Additional file 1: Table S1).

25(OH)D and methylation of vitamin D-related genes in the subcohort

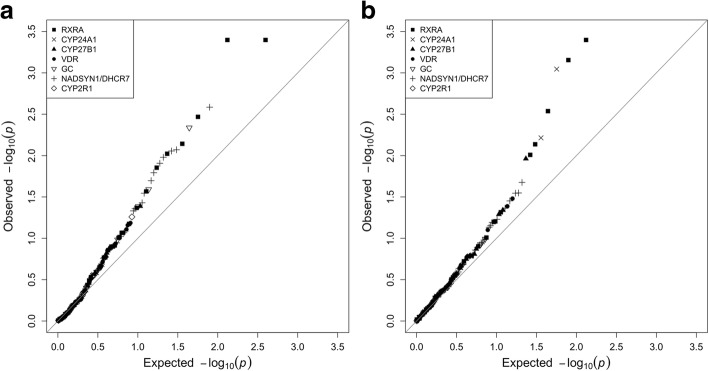

Of the 198 CpGs from vitamin D-related genes, cg21201924 (RXRA) had the lowest p value for association with 25(OH)D in the subcohort (p = 0.0004; Table 1 and Additional file 1: Table S2). Twenty-two other candidate CpGs were significantly associated with 25(OH)D, all but one of which were located in RXRA, NADSYN1/DHCR7, or GC. The large overall contrast between our results and those expected by chance is illustrated by a quantile-quantile plot (Fig. 1a).

Table 1.

CpGs in vitamin D-related genes with statistically significant (p < 0.05) associations with 25(OH)D; Sister Study subcohort (n = 1270)

| Rank | CpG | Gene / location type | Chromosome: position | Mean methylation level (SD) | Association with 25(OH)Da | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p value | |||||

| 1 | cg21201924 | RXRA / body | 9: 137251825 | 0.76 (0.042) | −0.020 | 0.0004 |

| 2 | cg02127980 | RXRA / body | 9: 137252116 | 0.40 (0.067) | −0.015 | 0.0004 |

| 3 | cg17559402b | NADSYN1 / body | 11: 71187890 | 0.97 (0.006) | −0.017 | 0.003 |

| 4 | cg02059519 | RXRA / body | 9: 137250935 | 0.83 (0.026) | −0.012 | 0.003 |

| 5 | cg09997530 | GC / body | 4: 72636217 | 0.91 (0.017) | 0.015 | 0.005 |

| 6 | cg04329455b | RXRA | 9: 137215364 | 0.96 (0.008) | 0.014 | 0.007 |

| 7 | cg00268518b | NADSYN1 / TSS200 | 11: 71164106 | 0.01 (0.001) | 0.011 | 0.008 |

| 8 | cg03146219 | NADSYN1 / body | 11: 71189514 | 0.47 (0.097) | −0.012 | 0.009 |

| 9 | cg13510651b | RXRA / body | 9: 137227772 | 0.94 (0.008) | −0.010 | 0.01 |

| 10 | cg03490288b | DHCR7 / body | 11: 71146658 | 0.97 (0.006) | 0.015 | 0.01 |

| 11 | cg05785753 | NADSYN1 / body | 11: 71189490 | 0.59 (0.074) | −0.010 | 0.01 |

| 12 | cg13687497 | RXRA / body | 9: 137249839 | 0.80 (0.023) | −0.010 | 0.01 |

| 13 | cg07793224b | NADSYN1 / body | 11: 71183180 | 0.97 (0.008) | 0.017 | 0.02 |

| 14 | cg26044621b | DHCR7 / 3´ UTR | 11: 71145665 | 0.94 (0.011) | 0.012 | 002 |

| 15 | cg04837494 | GC / 3´ UTR | 4: 72608149 | 0.85 (0.033) | 0.013 | 0.03 |

| 16 | cg14236758 | RXRA / body | 9: 137252129 | 0.48 (0.066) | −0.009 | 0.03 |

| 17 | cg04774822 | NADSYN1 / body | 11: 71165839 | 0.78 (0.033) | −0.009 | 0.03 |

| 18 | cg16151558b | DHCR7 / TSS1500 | 11: 71159853 | 0.02 (0.066) | 0.013 | 0.04 |

| 19 | cg20372759b | CYP27B1 / TSS1500 | 12: 58162287 | 0.97 (0.006) | −0.010 | 0.04 |

| 20 | cg24806812 | GC / body | 4: 72635202 | 0.93 (0.018) | 0.012 | 0.04 |

| 21 | cg14154547b | RXRA / body | 9: 137293309 | 0.92 (0.010) | −0.007 | 0.04 |

| 22 | cg07099121b | DHCR7 / 3´ UTR | 11: 71146096 | 0.98 (0.004) | −0.010 | 004 |

| 23 | cg16910670b | NADSYN1 | 11: 71215361 | 0.97 (0.005) | −0.011 | 0.05 |

TSS200 within 200 basepairs upstream of the transcription start site, TSS1500 within 1500 basepairs upstream of the transcription start site, UTR untranslated region

aEstimated change in methylation (logit(β)) per 10 ng/mL change in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D)

bIntraclass correlation coefficient < 0.5

Fig. 1.

Quantile-quantile plots for vitamin D-related genes. a The association between DNA methylation and 25(OH)D in the subcohort. b The association between DNA methylation-25(OH)D interactions and breast cancer risk in the case-cohort

25(OH)D-methylation interaction and breast cancer risk in the case-cohort

Eighteen of the 198 candidate CpGs showed evidence of interacting with 25(OH)D to affect breast cancer risk in the case-cohort sample (p < 0.05; Table 2 and Additional file 1: Table S3). This is more than expected by chance, as illustrated by the quantile-quantile plot (Fig. 1b). Nine of the eighteen had ICCs > 0.5. Only one was directly associated with breast cancer risk (cg10592901 in VDR, HR = 1.04, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.01–1.07).

Table 2.

Interacting effects of 25(OH)D and methylation at CpG sites in vitamin D-related genes on the 5-year risk of breast cancer (1024 cases, 1270 from subcohort, including 46 additional casesa): ratio of hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for CpGs with statistically significant interactions (p < 0.05)

| Rank | CpG site | Gene / location type | HR (95% CI) for methylation-breast cancer association | HR (95% CI) for methylation-breast cancer association, if 25(OH)D ≤ 38.0 ng/mL | HR (95% CI) for methylation-breast cancer association, if 25(OH)D > 38.0 ng/mL | Ratio of Hazard Ratios (95% CI)b | Interaction p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | cg21201924 | RXRA / body | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | 0.97 (0.93–1.01) | 1.18 (1.08–1.29) | 1.22 (1.10–1.34) | 7.0 × 10−5 |

| 2 | cg13786567 | RXRA / body | 1.01 (0.94–1.08) | 0.94 (0.87–1.02) | 1.34 (1.12–1.60) | 1.42 (1.17–1.73) | 4.0 × 10−4 |

| 3 | cg02127980 | RXRA / body | 1.00 (0.94–1.06) | 0.95 (0.88–1.01) | 1.22 (1.07–1.38) | 1.29 (1.11–1.49) | 7.0 × 10−4 |

| 4 | cg12978433 | CYP24A1 / 1st exon | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | 1.04 (1.00–1.07) | 0.93 (0.88–0.98) | 0.90 (0.84–0.96) | 9.0 × 10−4 |

| 5 | cg14154547c | RXRA / body | 0.96 (0.90–1.03) | 0.91 (0.84–0.98) | 1.17 (1.01–1.36) | 1.29 (1.09–1.53) | 0.003 |

| 6 | cg18956481c | CYP24A1 / 5´ UTR | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | 0.93 (0.88–0.98) | 0.92 (0.86–0.98) | 0.006 |

| 7 | cg13510651c | RXRA / body | 0.99 (0.93–1.06) | 0.95 (0.88–1.02) | 1.18 (1.03–1.35) | 1.24 (1.06–1.45) | 0.007 |

| 8 | cg14236758 | RXRA / body | 1.00 (0.94–1.06) | 0.96 (0.90–1.03) | 1.19 (1.03–1.37) | 1.23 (1.05–1.44) | 0.01 |

| 9 | cg09253762 | CYP27B1 / TSS1500 | 0.99 (0.95–1.04) | 0.96 (0.91–1.01) | 1.12 (1.01–1.24) | 1.16 (1.04–1.31) | 0.01 |

| 10 | cg18482822c | DHCR7 / body | 1.02 (0.97–1.06) | 0.99 (0.93–1.04) | 1.13 (1.02–1.24) | 1.14 (1.02–1.27) | 0.02 |

| 11 | cg05072492c | NADSYN1 / TSS1500 | 1.01 (0.96–1.06) | 0.97 (0.92–1.03) | 1.11 (1.00–1.24) | 1.15 (1.01–1.29) | 0.03 |

| 12 | cg11035813c | DHCR7 / TSS1500 | 1.02 (0.98–1.07) | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | 1.13 (1.02–1.24) | 1.13 (1.01–1.26) | 0.03 |

| 13 | cg14854850 | VDR / 3´ UTR | 0.99 (0.94–1.03) | 1.02 (0.97–1.07) | 0.90 (0.82–0.99) | 0.89 (0.79–0.99) | 0.03 |

| 14 | cg25588697c | DHCR7 / body | 1.01 (0.95–1.08) | 0.96 (0.89–1.05) | 1.14 (1.00–1.30) | 1.18 (1.01–1.38) | 0.04 |

| 15 | cg10592901 | VDR / body | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 1.06 (1.03–1.10) | 0.98 (0.92–1.05) | 0.92 (0.86–1.00) | 0.04 |

| 16 | cg12474705c | NADSYN1 / body | 0.96 (0.92–1.01) | 0.99 (0.94–1.05) | 0.88 (0.80–0.98) | 0.89 (0.79–1.00) | 0.04 |

| 17 | cg16984335c | CYP27B1 / body | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | 1.02 (0.97–1.06) | 0.92 (0.83–1.00) | 0.90 (0.81–1.00) | 0.05 |

| 18 | cg13941235 | RXRA / body | 1.00 (0.97–1.02) | 0.98 (0.95–1.01) | 1.04 (0.99–1.10) | 1.06 (1.00–1.13) | 0.05 |

CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, TSS1500 within 1500 basepairs upstream of the transcription start site, UTR Untranslated region

aAfter excluding those with missing covariate information

bChange in the methylation-breast cancer association for being in the 4th quartile of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) (≥ 38.0 ng/mL) versus the first three (< 38.0 ng/mL)—a value > 1.00 indicates that the estimated HR for the methylation-breast cancer association is higher among those with higher 25(OH)D levels; similarly, an RHR < 1.00 indicates that the estimated HR for the methylation-breast cancer association is higher among those with lower 25(OH)D levels

cIntraclass correlation coefficient < 0.5

The CpG with the smallest p value for the 25(OH)D-methylation interaction analysis was cg21201924 (RXRA). Among women with 25(OH)D levels > 38.0 ng/mL, each 0.1 change in logit(β) was associated with an 18% increase in the breast cancer hazard (HR = 1.18, 95% CI 1.08–1.29). By contrast, among women with 25(OH)D levels ≤ 38.0 ng/mL, each 0.1 change in logit(β) was associated with a 3% lower hazard of developing breast cancer (HR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.93–1.01). The corresponding RHR was 1.22 (95% CI 1.10–1.29; p = 7.0 × 10−5).

Six other RXRA CpGs (cg13786567, cg02127980, cg14154547, cg13510651, cg14236758, and cg13941235) also showed evidence of interacting with 25(OH)D to affect breast cancer risk. Other statistically significant sites included cg12978433 and cg18956481 in CYP24A1, cg09253762 and cg16984335 in CYP27B1, cg18482822, cg05072492, cg11035813, cg25588697, and cg12474705 in NADSYN1/DHCR7, and cg14854850 and cg10592901 in VDR. As we have previously reported that the protective association between 25(OH)D and breast cancer appears to be limited to postmenopausal women [3], we present postmenopause-specific analyses in Additional file 1: Tables S4 and S5 and Figure S1.The results were largely consistent with the analyses that included all breast cancers.

Epigenome-wide association study of 25(OH)D in subcohort or cases

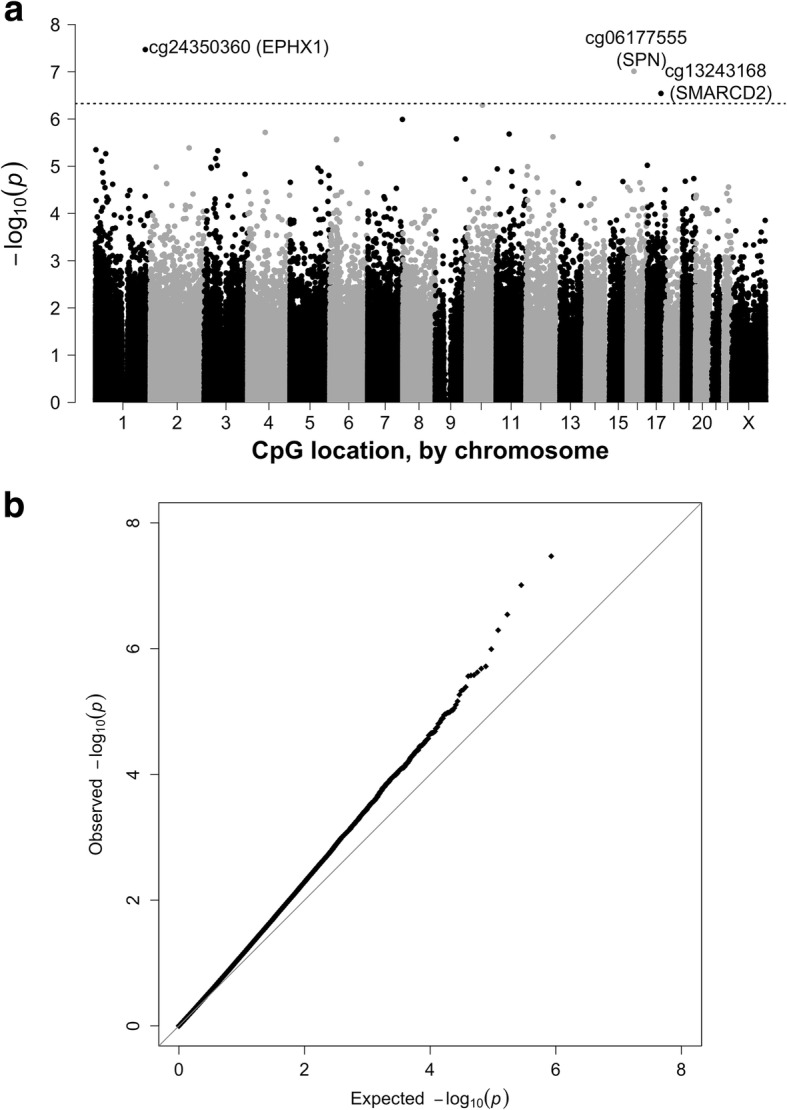

Within the subcohort, 25(OH)D was associated with methylation levels at three CpGs at q < 0.05 (Fig. 2a and Table 3). The CpG with the smallest p value was cg24350360 (EPHX1; p = 3.4 × 10−8), followed by cg06177555 (SPN; p = 9.8 × 10−8) and cg1324316 (SMARCD2; p = 2.9 × 10−7). Two other CpGs had q < 0.10: cg23761815 (SLC29A3; p = 5.1 × 10−7) and cg10401362 (DNAJB6; p = 1.0 × 10−6). The quantile-quantile plot (Fig. 2b) demonstrates that the observed p values systematically deviated from what was expected under the null hypothesis. For all five CpGs with q < 0.10, increases in serum 25(OH)D were associated with decreased methylation (Table 3; Additional file 1: Figure S2). All except cg24350360 (EPHX1) had ICCs > 0.5.

Fig. 2.

Manhattan plot (a) and quantile-quantile plot (b) for the associations between serum 25(OH)D levels (modeled continuously) and DNA methylation at 423,500 CpG sites among women in the subcohort (n = 1270 non-Hispanic white women). The reference line shows the cut-off for false discovery rate, q = 0.05

Table 3.

CpG sites associated with serum 25(OH)D levels in subcohort (q < 0.10)

| CpG site | Location (Chr:position) | Location type | Gene | Effect estimatea (95% CI) | p value | q value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg24350360 | 1:225997662b | TSS200 | EPHX1 | −0.04 (−0.06 to −0.03) | 3.4 × 10−8 | 0.01 |

| cg06177555 | 16:29678624 | 3′ UTR | SPN | −0.02 (−0.03 to −0.01) | 9.8 × 10−8 | 0.02 |

| cg13243168 | 17:61915833 | Body | SMARCD2 | −0.02 (−0.03 to −0.01) | 2.9 × 10−7 | 0.04 |

| cg23761815 | 10:73083123 | Body | SLC29A3 | −0.02 (−0.03 to −0.01) | 5.1 × 10−7 | 0.05 |

| cg10401362 | 7:157185402 | Body | DNAJB6 | −0.02 (−0.03 to −0.01) | 1.0 × 10−6 | 0.09 |

CI confidence interval, TSS200 within 200 basepairs upstream of the transcription start site, UTR untranslated region

aEstimated change in methylation (logit(β)) per 10 ng/mL change in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D)

bIntraclass correlation coefficient < 0.5

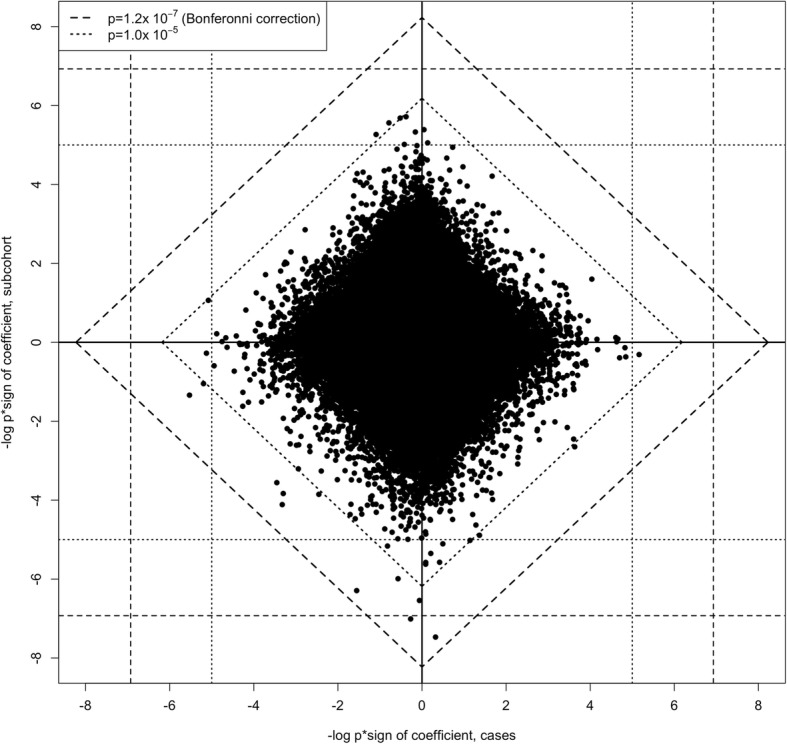

No CpGs were associated with 25(OH)D in case-only analyses (Additional file 1: Figure S3). When we compared the results of 25(OH)D-methylation association tests for the subcohort versus breast cancer cases (Fig. 3), no CpGs had a combined p < 1.2 × 10−7, the Bonferroni-corrected cut-point for significance. Sixteen CpGs with combined p values < 1.0 × 10−5 were deemed worthy of further investigation; all but two of which had ICCs > 0.5 (Table 4). Of the sixteen, nine had RHR p values < 0.05. Three of the latter nine were associated with 25(OH)D at q < 0.10 in the initial EWAS: cg13243168 (SMARCD2), cg23761815 (SLC29A3), and cg24350360 (EPHX1). Most of the CpGs with small Fisher combined p values were inversely associated with 25(OH)D in both cases and the subcohort.

Fig. 3.

Diamond plot comparing –log10 p value × sign of coefficient for the estimated association between 25(OH)D and logit(methylation): subcohort (n = 1270, including 46 breast cancer cases) versus other breast cancer cases (n = 1024). The broken lines show critical values for single (vertical and horizontal grid lines) and Fisher’s combined (diagonal lines) p values, based on χ2 tests with 2 (for single) and 4 (for combined) degrees of freedom

Table 4.

Ratio of hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the interaction between 25(OH)D and methylation on the risk of breast cancer within 5 years of enrollment (1024 cases, 1270 from subcohort, including 46 additional casesa); CpGs with Fisher combined p values < 1 × 10−5 for subcohort combined with case comparison

| Rank | CpG | Gene/ Location | 25(OH)D-methylation association, subcohort | 25(OH)D-methylation association, cases | Fisher combined p value | HR (95% CI) for methylation-breast cancer association | RHRs (95% CI)c | Interaction p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cofficientb | p value | Cofficientb | p value | |||||||

| 1 | cg08092930 | PPFIA1 | −0.03 | 1.3 × 10−5 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 8.5 × 10−6* | 1.01 (0.98–1.05) | 1.15 (1.06–1.24) | 6.3 × 10−4 |

| 2 | cg23761815 | SLC29A3 | −0.02 | 5.1 × 10−7 | − 0.01 | 0.03 | 2.7 × 10−7 | 1.13 (1.07–1.18) | 1.22 (1.08–1.38) | 0.002 |

| 3 | cg13243168 | SMARCD2 | −0.02 | 2.9 × 10−7 | − 7 × 10−4 | 0.87 | 4.0 × 10−6 | 1.05 (0.98–0.91) | 1.29 (1.09–1.51) | 0.002 |

| 4 | cg15544721 | PPP1R9A | −0.01 | 0.09 | −0.03 | 6.4 × 10−6 | 8.8 × 10−6 | 0.98 (0.94–1.03) | 0.87 (0.79–0.96) | 0.008 |

| 5 | cg11568290 | 5p15.1 | −0.02 | 1.4 × 10−4 | −0.01 | 0.004 | 7.7 × 10−6 | 1.15 (1.08–1.22) | 1.23 (1.05–1.44) | 0.009 |

| 6 | cg19420720 | P4HB | −0.01 | 0.002 | 0.02 | 2.3 × 10−4 | 8.1 × 10−6* | 1.01 (0.94–1.08) | 1.27 (1.06–1.52) | 0.01 |

| 7 | cg23839180 | FAM49A | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 3.0 × 10−6 | 2.3 × 10−6 | 0.97 (0.94–1.03) | 0.92 (0.86–0.98) | 0.01 |

| 8 | cg15320474d | UBD | 0.02 | 2.8 × 10−6 | − 0.01 | 0.16 | 7.0 × 10−6* | 0.98 (0.83–1.04) | 0.87 (0.77–0.99) | 0.03 |

| 9 | cg24350360d | EPHX1 | −0.04 | 3.4 × 10−8 | 0.01 | 0.48 | 3.1 × 10−7* | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | 1.08 (1.01–1.16) | 0.04 |

| 10 | cg22488164 | PLBD1 | −0.03 | 1.5 × 10−4 | −0.03 | 5.0 × 10−4 | 1.3 × 10−6 | 1.06 (1.02–1.10) | 0.93 (0.85–1.01) | 0.07 |

| 11 | cg10401362 | DNAJB6 | −0.02 | 1.0 × 10−6 | −0.01 | 0.27 | 4.4 × 10−6 | 1.02 (0.97–1.07) | 1.10 (0.98–1.24) | 0.10 |

| 12 | cg06177555 | SPN | −0.02 | 9.8 × 10−8 | −0.003 | 0.54 | 9.3 × 10−7 | 0.97 (0.91–1.03) | 1.12 (0.98–1.28) | 0.10 |

| 13 | cg11277126 | TRPC4AP | −0.02 | 7.7 × 10−5 | −0.02 | 4.8 × 10−4 | 6.7 × 10−7 | 1.04 (0.98–1.11) | 1.07 (0.92–1.24) | 0.39 |

| 14 | cg21527411 | GLYAT | 0.02 | 2.1 × 10−6 | −0.01 | 0.30 | 9.6 × 10−6* | 1.02 (0.97–1.07) | 0.95 (0.83–1.08) | 0.40 |

| 15 | cg09914444 | DMBX1 | 0.02 | 5.4 × 10−6 | −0.01 | 0.08 | 6.9 × 10−6* | 1.05 (1.01–1.10) | 0.96 (0.87–1.06) | 0.44 |

| 16 | cg23999318 | HIPK2 | −0.02 | 2.8 × 10−4 | −0.02 | 3.5 × 10−4 | 1.7 × 10−6 | 1.00 (0.94–1.05) | 1.00 (0.88–1.14) | 1.00 |

CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, RHR ratio of hazard ratio

aAfter excluding those with missing covariate information

bEstimated change in methylation (logit(β)) per 10 ng/mL change in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D)

cChange in the methylation-breast cancer association for being in the 4th quartile of 25(OH)D (> 38.0 ng/mL) versus the first three (≤ 38.0 ng/mL)—a value > 1.00 indicates that the estimated HR for the methylation-breast cancer association is higher among those with higher 25(OH)D levels; similarly, an RHR < 1.00 indicates that the estimated HR for the methylation-breast cancer association is higher among those with lower 25(OH)D levels

dIntraclass correlation coefficient < 0.5

*Effect estimate going in opposing direction for subcohort versus cases

Discussion

Among our a priori candidate loci, we found that methylation levels at CpGs in or near RXRA, NADSYN1/DHCR7, and GC were associated with serum 25(OH)D levels. In our larger EWAS analysis, CpGs in EPHX1, SPN, and SMARCD2 had epigenome-wide significant associations with serum 25(OH)D. To our knowledge, we are the first to report a link between these three genes and 25(OH)D and the first to study methylation-25(OH)D interactions in relation to breast cancer risk.

For candidate CpG analyses, the top hit for both the methylation-25(OH)D association analysis and the breast cancer interaction analyses was cg21201924, located in the gene body of RXRA. As previously noted, RXRA acts as a transcription factor with 1,25(OH)2D and VDR and changes to the gene’s expression and methylation levels could have widespread biological impacts. Changes in expression or methylation of GC, NADSYN1/DHCR7, and the other candidate genes may have less pervasive biological effects, but our findings support the hypothesis that these vitamin D-related genes and proteins may interact with circulating vitamin D levels to influence breast cancer risk.

Of the CpGs in or near vitamin D-related genes, most of those that were either associated with 25(OH)D or that showed evidence of interacting with 25(OH)D to affect breast cancer risk were located within gene bodies. Higher 25(OH)D levels tended to be associated with higher methylation, but there was no clear pattern linking CpG locations to the direction of the RHR in the interaction analysis.

None of the candidate CpGs from the vitamin D-related genes met the stringent criterion for statistical significance in the EWAS analysis, and thus there was no overlap between the genes identified in our EWAS and those reported previously to be associated with serum vitamin D levels. One of the two hits reported by Zhu et al. [33] (cg04623955 near DIO3) was also assessed in our sample, but we found no evidence of an association (p = 0.78). Other CpGs identified in their sample also failed to replicate, including cg23492043 (p = 0.64), cg00864867 (p = 0.15), and cg16826718 (p = 0.62). Eight CpGs reported by Florath et al. [34] were also assessed in our sample, but none were significantly associated with 25(OH)D (p values 0.09–0.85). These discrepancies could be related to differences in race, sex, or study design, but could also be the result of sampling variation.

As previously noted, vitamin D plays a role in immune response, including regulation of innate and adaptive immunity [9, 10], as well as detoxification [51]. Possible mechanisms for these actions could be through the 1,25(OH)2D-VDR-RXRA complex and its effects on gene transcription [12]. Although there is no established link between 25(OH)D or vitamin D metabolism and SPN, SMARCD2, SLC29A3, or DNAJB6 specifically, the observed associations between these genes and 25(OH)D could be related to VDR or other components of immune function.

EPHX1 encodes epoxide hydrolase, an enzyme that breaks down epoxides from xenobiotic aromatic compounds (e.g., polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, benzene) [52]. Further, EPHX1 regulation of detoxification via CYP450 enzymes has been shown to modulate the immune response in mice [53]. Although the direct mechanisms linking EPHX1 and vitamin D are unclear, an in-vivo study showed that 1,25(OH)2D3 increased the expression of EPHX1 and other phase I and phase II biotransformation enzymes in the intestinal tissue of vitamin D-deficient rats [54]. There is no known association between EPHX1 and breast cancer risk [55]. We do note that our results should be interpreted with caution as the EPHX1 CpG site that was strongly associated with 25(OH)D in our sample had a low ICC (< 0.5), meaning that the within-subject variability was larger than the between-subject variability.

SPN encodes a sialoglycoprotein expressed on leukocytes and platelets. Cell culture models have demonstrated that vitamin A and D metabolites upregulate SPN expression [56, 57]. SMARCD2 encodes a critical component of the SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable (SWI/SNF) chromatin remodeling complex, which uses ATP-derived energy to unwrap or restructure chromatin [58]. SMARCD subunits serve as a link between the SWI/SNF core complex and transcription regulators, including nuclear receptors such as VDR and RXR [59–61]. Although we found no prior reports of a direct link between these sites and breast cancer risk, recent studies have demonstrated that genes encoding for the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex are mutated in approximately 20% of all human tumors [62] and are considered to be critical tumor suppressors [58] and epigenetic regulators of tumorigenesis [63].

The effect measures we estimate for the interaction analysis, RHRs, measure the extent to which the hazard ratio for the 25(OH)D-breast cancer association depends on the epigenetics, as measured by methylation at a particular CpG locus. Because methylation and 25(OH)D were measured in the same blood samples, we cannot address the temporality of the identified associations to determine whether 25(OH)D influences methylation, methylation influences 25(OH)D, or a third factor influences both. Similarly, we can only assess whether the relationship between methylation and 25(OH)D is different for those who later developed breast cancer, suggesting multiplicative interaction, and not whether 25(OH)D or methylation acts as an effect modifier or mediator. Repeated measures of methylation and 25(OH)D would be needed to address temporality. Future studies could also help to determine the most appropriate cut-point for 25(OH)D levels in gene-by-environment interaction studies. We selected 38.0 ng/mL based on our previous results [3] and other findings supporting a threshold effect of similar magnitude [64], but we cannot be sure what levels have the most biological relevance for breast cancer risk.

We limited our sample to non-Hispanic white women to minimize the influence of genetic ancestry. As such, our results may not be fully generalizable. Our sample is also selective in that all participants had a sister diagnosed with breast cancer, and had, on average, approximately twice the risk of developing breast cancer themselves. Our findings are internally valid, but overrepresented risk factors (e.g., germline genetic or early childhood exposures) may inflate the magnitude of effect estimates if they influence the associations evaluated here.

Conclusions

Serum 25(OH)D concentrations were associated with methylation levels at candidate CpGs in vitamin D-related genes and three genes with links to immune function or regulation of VDR. Methylation levels of some of these CpGs may interact with vitamin D to affect breast cancer risk. These results contribute to our understanding of the relationship between vitamin D and DNA methylation and the impact of vitamin D on breast cancer risk.

Additional file

Table S1. Characteristics of participants included in the vitamin D and methylation substudy (Sister Study, 2003–2009); only non-Hispanic white women included. Table S2. Associations between 25(OH)D and methylation at CpG sites in vitamin D-related genes (p > 0.05); Sister Study subcohort (n = 1270). Table S3. Interaction effects of 25(OH)D and methylation at CpG sites in vitamin D-related genes on the 5-year risk of breast cancer (1024 cases, 1270 from subcohort, including 46 additional cases): ratio of hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for CpGs with interaction p values > 0.05. Table S4. Interacting effects of 25(OH)D and CpG sites in vitamin D-related genes on the 5-year risk of post-menopausal breast cancer (852 cases, 1026 from subcohort, including 41 additional cases): ratio of hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Table S5. Ratio of hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the interaction between 25(OH)D and methylation on the 5-year risk of postmenopausal breast cancer (852 cases, 1026 from subcohort, including 41 additional cases); CpGs with Fisher combined p values < 1 × 10−5 for subcohort versus case comparison. Figure S1. Quantile-quantile plot for the association between the epigenetic-by-25(OH)D interaction term and breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women. Figure S2. Volcano plot for the associations between serum 25(OH)D levels (modeled continuously) and DNA methylation at 423,500 CpG sites among 1270 non-Hispanic white women randomly selected from the Sister Study cohort (2003–2009). Figure S3. Manhattan plot (top) and quantile-quantile plot (bottom) for the association between DNA methylation at 423,500 CpG sites and serum 25(OH)D among non-Hispanic white women with breast cancer (n = 1024; excluding those who were selected as part of subcohort). No CpGs were statistically significant at q < 0.05. (DOCX 419 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs. Alexandra White and Jacob Kresovich for their comments on an early draft of this paper.

Funding

This work was supported by an Office of Dietary Supplement Research Scholars Program Grant (to KMO) and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (projects Z01-ES044005 to DPS; Z01-ES102245 to CRW; and Z01-ES049033 to JAT).

Availability of data and materials

Requests for data, including the data used in this manuscript, are welcome. De-identified data is made available upon request as described on the study website (https://sisterstudy.niehs.nih.gov/English/data-requests.htm). The Sister Study is an ongoing prospective study. The data sharing policy was developed to protect the privacy of study participants and is consistent with study informed consent documents as approved by the NIEHS Institutional Review Board.

Abbreviations

- 1,25(OH)2D

1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D

- 25(OH)D

25-Hydroxyvitamin D

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- EWAS

Epigenome-wide association study

- HR

Hazard ratio

- ICC

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- LC/MS

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- RHR

Ratio of hazard ratios

- RXRA

Retinoid X receptor alpha

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- VDR

Vitamin D receptor

Authors’ contributions

DPS, JAT, and CRW designed the parent study and acquired the data. ZX and KMO performed statistical analyses. KMO, HKK, JAT, and CRW interpreted the data. KMO drafted the manuscript, with guidance from JAT and CRW and substantial contributions from HKK. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final draft.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All women provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the institutional review boards of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the Copernicus Group.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Jack A. Taylor and Clarice R. Weinberg contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13058-018-0994-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Katie M. O’Brien, Phone: (984) 287-3753, Email: obrienkm2@niehs.nih.gov

Dale P. Sandler, Email: sandler@niehs.nih.gov

Zongli Xu, Email: xuz@niehs.nih.gov.

H. Karimi Kinyamu, Email: kinyamu@niehs.nih.gov.

Jack A. Taylor, Email: taylor@niehs.nih.gov

Clarice R. Weinberg, Email: weinberg@niehs.nih.gov

References

- 1.Autier P, Boniol M, Pizot C, Mullie P. Vitamin D status and ill health: a systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:76–89. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gandini S, Boniol M, Haukka J, Byrnes G, Cox B, Sneyd MJ, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and colorectal, breast and prostate cancer and colorectal adenoma. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:1414–1424. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Brien KM, Sandler DP, Taylor JA, Weinberg CR. Serum vitamin D and risk of breast cancer within five years. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125:077004. doi: 10.1289/EHP943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schöttker B, Jorde R, Peasey A, Thorand B, Jansen EHJM, de GL, et al. Vitamin D and mortality: meta-analysis of individual participant data from a large consortium of cohort studies from Europe and the United States. BMJ. 2014;348:g3656. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim Y, Je Y. Vitamin D intake, blood 25(OH)D levels, and breast cancer risk or mortality: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2772–2784. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holick MF, Herman RH, Award M. Vitamin D: importance in the prevention of cancers, type 1 diabetes, heart disease, and osteoporosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:362–371. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.3.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trump DL, Hershberger PA, Bernardi RJ, Ahmed S, Muindi J, Fakih M, et al. Anti-tumor activity of calcitriol: pre-clinical and clinical studies. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;89–90:519–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welsh J, Wietzke JA, Zinser GM, Byrne B, Smith K, Narvaez CJ. Vitamin D-3 receptor as a target for breast cancer prevention. J Nutr. 2003;133:2425S–2433S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.7.2425S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei R, Christakos S. Mechanisms underlying the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity by vitamin D. Nutrients. 2015;7:8251–8260. doi: 10.3390/nu7105392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prietl B, Treiber G, Pieber TR, Amrein K. Vitamin D and immune function. Nutrients. 2013;5:2502–2521. doi: 10.3390/nu5072502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheskis B, Freedman LP. Ligand modulates the conversion of DNA-bound vitamin D3 receptor (VDR) homodimers into VDR-retinoid X receptor heterodimers. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3329–3338. doi: 10.1128/MCB.14.5.3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goeman F, De Nicola F, De Meo PDO, Pallocca M, Elmi B, Castrignano T, et al. VDR primary targets by genome-wide transcriptional profiling. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. Elsevier Ltd. 2014;143:348–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fetahu IS, Höbaus J, Kállay EO. Vitamin D and the epigenome. Front Physiol. 2014;5:164. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jjingo D, Conley AB, Yi SV, Lunyak VV, Jordan IK. On the presence and role of human gene-body DNA methylation. Oncotarget. 2012;3:462–474. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee KWK, Pausova Z. Cigarette smoking and DNA methylation. Front Genet. 2013;4:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harlid S, Xu Z, Panduri V, Sandler DP, Taylor JA. CpG sites associated with cigarette smoking: analysis of epigenome-wide data from the sister study. Env Heal Perspect. 2014;122:673–678. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joubert BR, Felix JF, Yousefi P, Bakulski KM, Just AC, Breton C, et al. DNA methylation in newborns and maternal smoking in pregnancy: genome-wide consortium meta-analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:680–696. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joehanes R, Just AC, Marioni RE, Pilling LC, Reynolds LM, Mandaviya PR, et al. Epigenetic signatures of cigarette smoking. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2016;9:436–447. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markunas CA, Xu Z, Harlid S, Wade PA, Lie RT, Taylor JA, et al. Identification of DNA methylation changes in newborns related to maternal smoking during pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:1147–1153. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson LE, Harlid S, Xu Z, Sandler DP, Taylor JA. An epigenome-wide study of body mass index and DNA methylation in blood using participants from the sister study cohort. Int J Obes. 2016;41:194–199. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hair BY, Xu Z, Kirk EL, Harlid S, Sandhu R, Robinson WR, et al. Body mass index associated with genome-wide methylation in breast tissue. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;151:453–463. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3401-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaissière T, Hung RJ, Zaridze D, Moukeria A, Cuenin C, Fasolo V, et al. Quantitative analysis of DNA methylation profiles in lung cancer identifies aberrant DNA methylation of specific genes and its association with gender and cancer risk factors. Cancer Res. 2009;69:243–252. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friso S, Udali S, De Santis D, Choi S-W. One-carbon metabolism and epigenetics. Mol Aspects Med. 2016;54:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steegers-Theunissen RP, Obermann-Borst SA, Kremer D, Lindemans J, Siebel C, Steegers EA, et al. Periconceptional maternal folic acid use of 400 μg per day is related to increased methylation of the IGF2 gene in the very young child. PLoS One. 2009;4:1–5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang S, Wang L, Guan Y, Shangguan S, Du Q, Wang Y, et al. Long interspersed nucleotide element-1 hypomethylation in folate-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114:1549–1558. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi SW, Friso S, Ghandour H, Bagley PJ, Selhub J, Mason JB. Vitamin B-12 deficiency induces anomalies of base substitution and methylation in the DNA of rat colonic epithelium. J Nutr. 2004;134:750–755. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.4.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheong HS, Lee HC, Park BL, Kim H, Jang MJ, Han YM, et al. Epigenetic modification of retinoic acid-treated human embryonic stem cells. BMB Rep. 2010;43:830–835. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2010.43.12.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung I, Karpf AR, Muindi JR, Conroy JM, Nowak NJ, Johnson CS, et al. Epigenetic silencing of CYP24 in tumor-derived endothelial cells contributes to selective growth inhibition by calcitriol. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8704–8714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608894200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson CS, Chung I, Trump DL. Epigenetic silencing of CYP24 in the tumor microenvironment. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121:338–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fu B, Wang H, Wang J, Barouhas I, Liu W, Shuboy A, et al. Epigenetic regulation of BMP2 by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 through DNA methylation and histone modification. PLoS One. 2013;8:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stefanska B, Salamé P, Bednarek A, Fabianowska-Majewska K. Comparative effects of retinoic acid, vitamin D and resveratrol alone and in combination with adenosine analogues on methylation and expression of phosphatase and tensin homologue tumour suppressor gene in breast cancer cells. Br J Nutr. 2012;107:781–790. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511003631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rawson JB, Sun Z, Dicks E, Daftary D, Parfrey PS, Green RC, et al. Vitamin D intake is negatively associated with promoter methylation of the Wnt antagonist gene DKK1 in a large group of colorectal cancer patients. Nutr Cancer. 2012;64:919–928. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2012.711418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu H, Wang X, Shi H, Su S, Harshfield GA, Gutin B, et al. A genome-wide methylation study of severe vitamin D deficiency in African American adolescents. J Pediatr. 2013;162:1004–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Florath I, Schöttker B, Butterbach K, Bewerunge-Hudler M, Brenner H, Schottker B, et al. Epigenome-wide search for association of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration with leukocyte DNA methylation in a large cohort of older men. Epigenomics. 2016;8:487–499. doi: 10.2217/epi.16.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suderman M, Stene LC, Bohlin J, Page CM, Holvik K, Parr CL, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D in pregnancy and genome wide cord blood DNA methylation in two pregnancy cohorts (MoBa and ALSPAC) J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;159:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chavez Valencia RA, Martino DJ, Saffery R, Ellis JA. In vitro exposure of human blood mononuclear cells to active vitamin D does not induce substantial change to DNA methylation on a genome-scale. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;141:144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hübner U, Geisel JJJ, Kirsch SH, Kruse V, Bodis M, Klein C, et al. Effect of 1 year B and D vitamin supplementation on LINE-1 repetitive element methylation in older subjects. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2013;51:649–655. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2012-0624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nair-Shalliker V, Dhillon V, Clements M, Armstrong BK, Fenech M. The association between personal sun exposure, serum vitamin D and global methylation in human lymphocytes in a population of healthy adults in South Australia. Mutat Res. 2014;765:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu H, Bhagatwala J, Huang Y, Pollock NK, Parikh S, Raed A, et al. Race/ethnicity-specific association of vitamin D and global DNA methylation: cross-sectional and interventional findings. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sandler DP, Hodgson ME, Deming-Halverson SL, Juras PJ, D’Aloisio AD, Suarez L, et al. The sister study: baseline methods and participant characteristics. Env Heal Perspect 2017;In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Prentice RL. A case-cohort design for epidemiologic cohort studies and disease prevention trials. Biometrika. 1986;73:1–11. doi: 10.1093/biomet/73.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barlow WE, Ichikawa L, Rosner D, Izumi S. Analysis of case-cohort designs. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00102-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu Z, Niu L, Li L, Taylor JA. ENmix: a novel background correction method for Illumina HumanMethylation450 BeadChip. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;44:e20. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu Z, Langie SAS, De Boever P, Taylor JA, Niu LRELIC. A novel dye-bias correction method for Illumina methylation BeadChip. BMC Genomics. 2017;18:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3406-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Niu L, Xu Z, Taylor JA. RCP: a novel probe design bias correction method for Illumina methylation BeadChip. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:2659–2663. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen J, Just AC, Schwartz J, Hou L, Jafari N, Sun Z, et al. CpGFilter: model-based CpG probe filtering with replicates for epigenome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics. 2015;32:469–471. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.University of California Santa Cruz, Genome Browser. Available from: http://genome.ucsc.edu/. [cited 2017 Mar 15]

- 48.Houseman EA, Kelsey KT, Wiencke JK, Marsit CJ. Cell-composition effects in the analysis of DNA methylation array data: a mathematical perspective. BMC Bioinformatics. 2015;16:95. doi: 10.1186/s12859-015-0527-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fisher RA. Statistical methods for research workers. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd; 1925. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haussler MR, Whitfield GK, Kaneko I, Haussler CA, Hsieh D, Hsieh JC, et al. Molecular mechanisms of vitamin D action. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;92:77–98. doi: 10.1007/s00223-012-9619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Decker M, Arand M, Cronin A. Mammalian epoxide hydrolases in xenobiotic metabolism and signalling. Arch Toxicol. 2009;83:297–318. doi: 10.1007/s00204-009-0416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gilroy DW, Edin ML, De Maeyer RPH, Bystrom J, Newson J, Lih FB, et al. CYP450-derived oxylipins mediate inflammatory resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113:E3240–E3249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521453113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kutuzova GD, DeLuca HF. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 regulates genes responsible for detoxification in intestine. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;218:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tan X, Wang YY, Chen XY, Xian L, Guo JJ, Liang GB, et al. Quantitative assessment of the effects of the EPHX1 Tyr113His polymorphism on lung and breast cancer. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13:7437–7446. doi: 10.4238/2014.September.12.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Babina M, Weber S, Henz BM. CD43 (leukosialin, sialophorin) expression is differentially regulated by retinoic acids. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1147–1151. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Turzová M, Hunáková L, Duraj J, Speiser P, Sedlák J, Chorváth B. Modulation of leukosialin (sialophorin, CD43 antigen) on the cell surface of human hematopoietic cell lines induced by cytokins, retinoic acid and 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D3. Neoplasma. 1993;40:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilson BG, Roberts CWM. SWI/SNF nucleosome remodellers and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:481–492. doi: 10.1038/nrc3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hsiao P-W, Fryer CJ, Trotter KW, Wang W, Archer TK. BAF60a mediates critical interactions between nuclear receptors and the BRG1 chromatin-remodeling complex for transactivation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6210–6220. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.17.6210-6220.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koszewski NJ, Henry KW, Lubert EJ, Gravatte H, Noonan DJ. Use of a modified yeast one-hybrid screen to identify BAF60a interactions with the vitamin D receptor heterodimer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;87:223–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Flajollet S, Lefebvre B, Cudejko C, Staels B, Lefebvre P. The core component of the mammalian SWI/SNF complex SMARCD3/BAF60c is a coactivator for the nuclear retinoic acid receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;270:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kadoch C, Hargreaves DC, Hodges C, Elias L, Ho L, Ranish J, et al. Proteomic and bioinformatic analysis of mammalian SWI/SNF complexes identifies extensive roles in human malignancy. Nat Genet. 2013;45:592–601. doi: 10.1038/ng.2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Masliah-Planchon J, Bièche I, Guinebretière J-M, Bourdeaut F, Delattre O. SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling and human malignancies. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2015;10:145–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012414-040445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bauer SR, Hankinson SE, Bertone-Johnson ER, Ding EL. Plasma vitamin D levels, menopause, and risk of breast cancer: dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Med. 2013;92:123–131. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3182943bc2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Characteristics of participants included in the vitamin D and methylation substudy (Sister Study, 2003–2009); only non-Hispanic white women included. Table S2. Associations between 25(OH)D and methylation at CpG sites in vitamin D-related genes (p > 0.05); Sister Study subcohort (n = 1270). Table S3. Interaction effects of 25(OH)D and methylation at CpG sites in vitamin D-related genes on the 5-year risk of breast cancer (1024 cases, 1270 from subcohort, including 46 additional cases): ratio of hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for CpGs with interaction p values > 0.05. Table S4. Interacting effects of 25(OH)D and CpG sites in vitamin D-related genes on the 5-year risk of post-menopausal breast cancer (852 cases, 1026 from subcohort, including 41 additional cases): ratio of hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Table S5. Ratio of hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the interaction between 25(OH)D and methylation on the 5-year risk of postmenopausal breast cancer (852 cases, 1026 from subcohort, including 41 additional cases); CpGs with Fisher combined p values < 1 × 10−5 for subcohort versus case comparison. Figure S1. Quantile-quantile plot for the association between the epigenetic-by-25(OH)D interaction term and breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women. Figure S2. Volcano plot for the associations between serum 25(OH)D levels (modeled continuously) and DNA methylation at 423,500 CpG sites among 1270 non-Hispanic white women randomly selected from the Sister Study cohort (2003–2009). Figure S3. Manhattan plot (top) and quantile-quantile plot (bottom) for the association between DNA methylation at 423,500 CpG sites and serum 25(OH)D among non-Hispanic white women with breast cancer (n = 1024; excluding those who were selected as part of subcohort). No CpGs were statistically significant at q < 0.05. (DOCX 419 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Requests for data, including the data used in this manuscript, are welcome. De-identified data is made available upon request as described on the study website (https://sisterstudy.niehs.nih.gov/English/data-requests.htm). The Sister Study is an ongoing prospective study. The data sharing policy was developed to protect the privacy of study participants and is consistent with study informed consent documents as approved by the NIEHS Institutional Review Board.