Abstract

Patient: Male, 58

Final Diagnosis: Posterior cortical atrophy

Symptoms: Oculomotor apraxia • simultagnosia • visual impairment

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: tDCS and cognitive rehabilitation

Specialty: Neurology

Objective:

Unusual or unexpected effect of treatment

Background:

Posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) is a neurodegenerative syndrome that accounts for 5% of the atypical presentation of Alzheimer disease (AD). To date, only a few studies have explored the effect of non-pharmacological treatment in PCA patients and no studies have evaluated the efficacy of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in this disorder.

Case Report:

A 58-year-old PCA patient underwent a cognitive rehabilitation treatment followed by 2 cycles of tDCS stimulation. The effects of both treatments were monitored over time with a standardized task-based fMRI protocol and with a neuropsychological assessment. Improvements in cognitive abilities, increased fMRI activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and deactivation of the default mode network during the Stroop test performance were detected after each session treatment.

Conclusions:

This combined approach lead to both cognitive improvements and neurophysiological adaptive changes, however, further studies on a larger cohort are needed to confirm these preliminary results.

MeSH Keywords: Cognitive Therapy, Dementia, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

Background

Posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) is a neurodegenerative syndrome that typically presents in patients who are in their mid-50s or early 60s; it is characterized by visuoperceptual deficit followed by a progressive cognitive decline and account for 5% of the atypical presentation of Alzheimer disease (AD) [1]. The core symptoms are mainly related to visuospatial disorders, including simultagnosia, optic ataxia, oculomotor disorders, visual inattention, and topographical disorientation [2]. Although episodic memory and insight are initially relatively preserved, progression of the disease ultimately leads to a more diffuse pattern of cognitive dysfunction; deficits in writing, reading, numeracy, literacy, and praxis may also be present [1]. Recent studies have demonstrated the potential therapeutic effect of some non-pharmacological interventions such as non-invasive brain stimulation techniques. Among these methods, transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) has proven to be a promising tool for the treatment of cognitive-behavioral deficits [3]. To date, only a few studies have explored the effect of non-pharmacological treatment in PCA patients and no studies have evaluated the efficacy of tDCS in this disorder. We report the effects of a combined approach composed by cognitive rehabilitation treatment and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in a patient with PCA. A task-based fMRI and a neuropsychological (NPS) assessment was used to monitor patient’s performance and neurophysiological changes over time.

Case Report

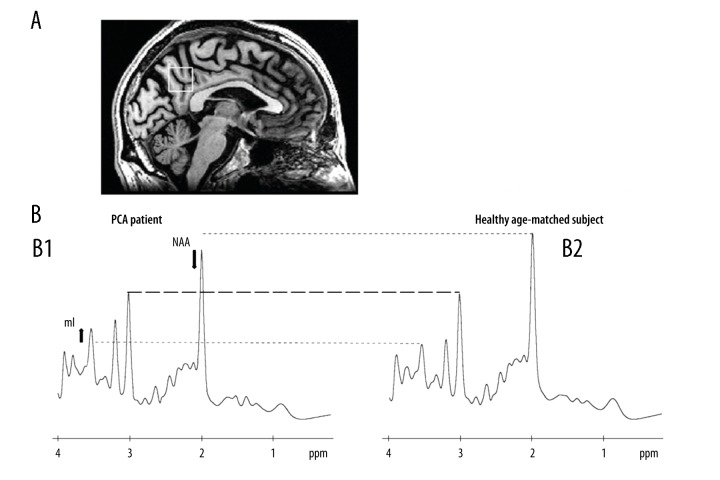

A 58-year-old Caucasian male (right-handed, 17 years of education) was referred to the IRCCS-Istituto delle Scienze Neurologiche, Bologna (IT). At the age of 56, he started complaining about light hypersensitivity and difficulties in following lines while reading. During the last 6 months, he also presented difficulties in identifying dimension and spatial orientation of static objects. The neurological examination showed simultanagnosia and oculomotor apraxia. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF analysis) demonstrated an increase both in total Tau protein (>1200 pg/mL; normal values=117±127 pg/mL) and in P-tau/amyloid-beta ratio (0.24; values >0.08 are consistent with a biochemical AD profile [2]). The MMSE was 29/30 and the NPS evaluation revealed deficits in immediate visual memory (P=11.6; cutoff >13.85), visuo-spatial short term memory (P=2.5, cutoff >3.46), visual gestaltic perception (P=0; cutoff >2.25) and slower reaction time (seconds) in tests measuring response inhibition (P=31; cutoff <27.5) and visual attention (P=105; cutoff <93). Brain MRI volume analysis (FreeSurfer, https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/) showed, in comparison to a matched group of healthy participants, a volume reduction in occipito-parietal cortex (−21%), temporal cortex (−17%), and frontal cortex (−11%) (Figure 1). Proton MR spectroscopy (1H-MRS) analysis (LCModel software, version 6.3) showed reduced levels of the neuro-axonal marker N-Acetyl-Aspartate (NAA), and increased levels of myoinositol (mL), glial marker, in the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC); ratio NAA/ml=1.34 (healthy controls=1.81±0.15) (Figure 2). According to these clinical and MRI findings, the diagnosis of PCA was established [1].

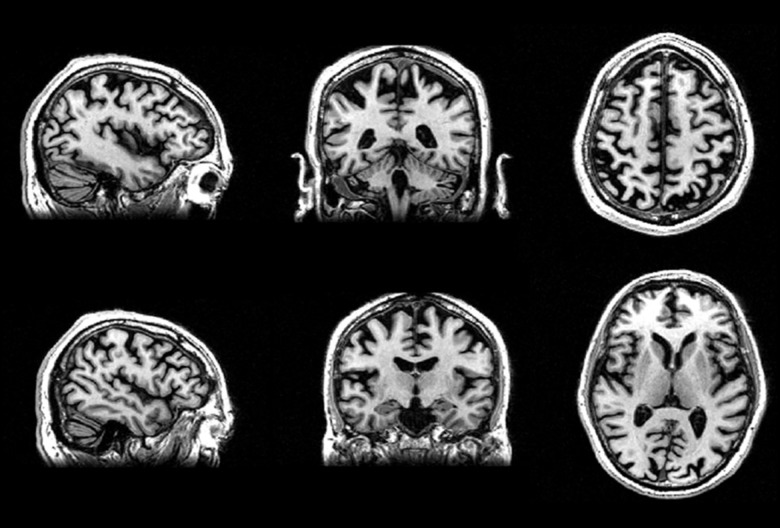

Figure 1.

High resolution 3D T1-weighted FSPGR images showed volume reduction in occipito-parietal, temporal, and frontal areas.

Figure 2.

(A) Voxel localization (PCC) projected onto sagittal plane of patient’s own T1-W image; (B) 1H-MRS spectra indicating resonance of interest (NAA – N-acetyl-aspartate; mI – myo-inositol). (B1) PCA patient. (B2) Example of 1H-MRS spectrum of a healthy elderly patient with similar demographic features.

The patient underwent cognitive rehabilitation followed by 2 cycles of tDCS. The cognitive treatment was composed by 12 sessions (1 hour each, 1 time per week for 3 months) and consisted of both computerized and “paper and pencil” tasks, specifically designed to target multiple cognitive domains. The 2 cycles of tDCS, targeting the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPC), consisted of 20 minutes of stimulation at 2 mA per session each, 5 days a week for 4 weeks.

The stimulation was performed using an HDC Stim constant-current stimulator (Newronika s.r.l., Milano, Italy), isolated from the main circuit, and powered by a low voltage battery. The stimulator was connected to a pair of sponge-tipped electrodes, bathed in saline solution, and covered by electroconductive gel to reduce impedance. Current density was 0.057 mA/cm2, below the relevant safety limit [4]. The active electrode was placed on the scalp over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, identified as F3 in the international 10–20 EEG electrode system. The reference electrode was placed on the right shoulder to avoid any interference from cerebral areas that would be present with a cranial placement [5].

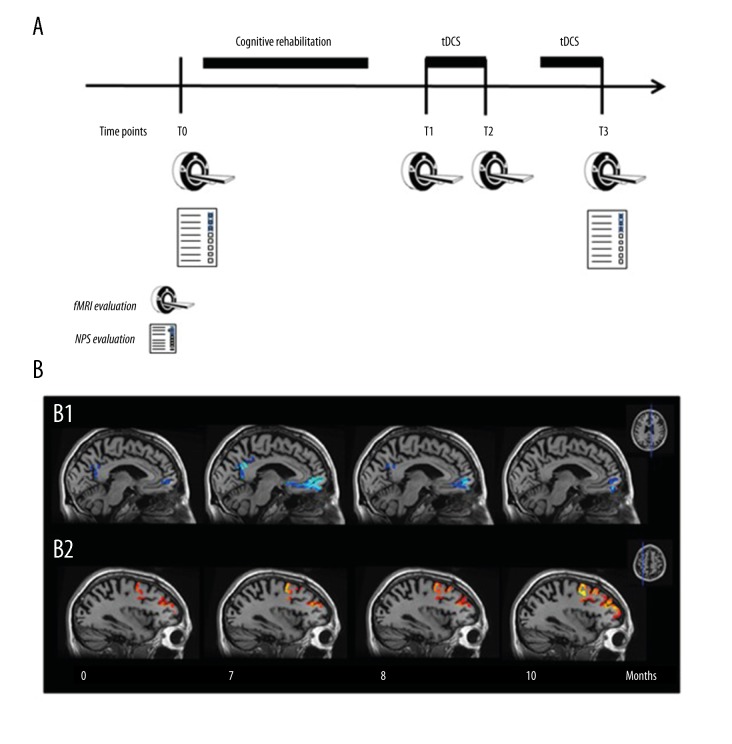

The effects of both treatments were monitored with a standardized task-based fMRI protocol at baseline (T0), after the cycle of cognitive rehabilitation (T1) (duration of the treatment 3 months), and after the first (T2) and the second cycle of tDCS (T3) (duration of each tDCS cycle 1 month). The assessment of brain hemodynamic changes in response to a specific cognitive task (i.e., Stroop task) allows for simultaneous monitoring on a neurophysiological and cognitive level, enabling direct assessment of both measures. Furthermore, a complete NPS evaluation was also administered at T0 and T3.

fMRI was acquired in a 1.5 T scanner while the patient was performing a word-color Stroop test. The extent of activation was evaluated in the cortical regions stimulated during the tDCS cycles, the left DLPC and the contralateral side, regions usually involved in Stroop-related cognitive processes [6]. The extent of deactivation was evaluated in the core hubs of the default mode network (DMN), the medial orbital prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the precuneus, usually deactivated when the mind is engaged in cognitive tasks [7]. These regions of interest (ROIs) were identified using the automatic parcellation of the high-resolution images (GR-EPI) provided by the ad hoc method for longitudinal studies of Freesurfer software (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/). For the selected ROIs, blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) signal intensities were quantified by using the maximum Z-score.

After the cognitive rehabilitation treatment (T1), our patient showed an improvement on the fMRI Stroop test performance (accuracy from 26% at T0 to 40% at T1); this cognitive improvement was also maintained after the first tDCS cycle (accuracy at T2=31%) and after the second tDCS cycle (accuracy at T3=30.8%). An improvement in immediate visual memory, visual gestaltic perception, visual attention, and visuo-spatial short-term memory was detected at T3, despite a mild decrease in the MMSE score (from 29 to 27) and in spatial attention. After the first and the second tDCS cycle (T2 and T3), the brain hemodynamic response (BOLD signal), increased bilaterally in the DLPC in comparison to T0 and T1; higher deactivation of DMN, specifically in the mPFC and precuneus was also detected after both tDCS cycles (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

(A) Timeline of the experimental study design. (B) Longitudinal fMRI deactivation (B1, blue scale) and activation (B2, red scale) maps resulting from the word-color modified Stroop test administration (P<0.05 cluster-based corrected, displayed on co-registered and averaged high-resolution T1 images). Results are displayed only in the selected ROIs. At visual inspection, it is detectable an increase of deactivation of DMN in the region of medial orbital prefrontal cortex and precuneus (B1) and an increase of activation of DLPC over time (B2). tDCS – transcranial direct current stimulation; fMRI – funtional magnetic resonance imaging; NPS – neuropsychological.

Discussion

This is the first longitudinal study on a PCA patient treated with a combination of cognitive rehabilitation and tDCS stimulation of prefrontal cortices. Cognitive and neurophysiological changes were monitored after each session through a standardized task-based fMRI protocol, enabling a direct assessment of both treatments. This study provides evidence that this approach modifies intrinsic brain activity, increasing DLPC activation and DMN deactivation. These neurophysiological changes seem to facilitate reallocation of cerebral resources to support task performance, thus promoting improvements at the cognitive level. These results are in line with previous studies with healthy young volunteers that suggested a reconfiguration of intrinsic brain activity networks after a tDCS stimulation [8].

Previous studies demonstrated the efficacy of combined approaches (cognitive rehabilitation and brain stimulation) in patients with acute stroke [9]. In the last few years, it has also been demonstrated that the synergetic use of cognitive rehabilitation and tDCS appeared to slow down the cognitive decline in neurodegenerative diseases (i.e., in a patient with AD) and these improvements lasted approximately 3 months [10].

PCA patients showed a variety of cognitive deficits and this study demonstrated that the use of a combined approach (cognitive rehabilitation and brain stimulation techniques) lead to both cognitive improvements and neurophysiological adaptive changes. Behavioral fMRI could be considered a useful tool in monitoring the effect of these non-pharmacological interventions.

Certain limitations of the study should be borne in mind in interpreting these data. This is a case study with a single PCA patient, therefore, the results may not be generalized; this protocol should be replicated with a bigger sample to establish more reliability. Furthermore, longer follow-ups are needed to explore whether cognitive improvements and neurophysiological changes are also maintained over time.

Conclusions

A combination of cognitive rehabilitation and tDCS stimulation of prefrontal cortices lead to both cognitive improvements and neurophysiological adaptive changes in a PCA patient. A reconfiguration of intrinsic brain activity networks seems to facilitate reallocation of cerebral resources to support task performance, thus also promoting improvements at the cognitive level. Behavioral fMRI could be considered a useful tool in monitoring the effect of these non-pharmacological interventions.

References:

- 1.Crutch SJ, Schott JM, Rabinovici GD, et al. Consensus classification of posterior cortical atrophy. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;17:30040–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caine D. Posterior cortical atrophy: A review of the literature. Neurocase. 2004;10(5):382–85. doi: 10.1080/13554790490892239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lefaucheur J-P. A comprehensive database of published tDCS clinical trials (2005–2016) MOTS CLÉS. Neurophysiol Clin Neurophysiol. 2016;46:319–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poreisz C, Boros K, Antal A, Paulus W. Safety aspects of transcranial direct current stimulation concerning healthy subjects and patients. Brain Res Bull. 2007;72(4–6):208–14. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cappa SF, Sandrini M, Rossini PM, et al. The role of the left frontal lobe in action naming: rTMS evidence. Neurology. 2002;59(5):720–23. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.5.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vanderhasselt MA, De Raedt R, Baeken C. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and stroop performance: Tackling the lateralization. Psychon Bull Rev. 2009;16(3):609–12. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.3.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anticevic A, Cole MW, Murray JD, et al. The role of default network deactivation in cognition and disease. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16(12):584–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peña-Gómez C, Sala-Lonch R, Junqué C, et al. Modulation of large-scale brain networks by transcranial direct current stimulation evidenced by resting-state functional MRI. Brain Stimul. 2012;5(3):252–63. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim J, Yim J. Effects of high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with task-oriented mirror therapy training on hand rehabilitation of acute stroke patients. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:743–50. doi: 10.12659/MSM.905636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Penolazzi B, Bergamaschi S, Pastore M, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation and cognitive training in the rehabilitation of Alzheimer disease: A case study. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2015;25(6):799–817. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2014.977301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]