Abstract

Objectives

To examine (1) the effectiveness of therapeutic play in reducing anxiety and negative emotional manifestations among children undergoing cast-removal procedures and (2) the satisfaction of parents and cast technicians with cast-removal procedures.

Design

A randomised controlled trial.

Setting

An orthopaedic outpatient department of a regional teaching hospital in Hong Kong.

Participants

Children (n=208) aged 3–12 undergoing cast-removal procedure were invited to participate.

Interventions

Eligible children were randomly allocated to either the intervention (n=103) or control group (n=105) and stratified by the two age groups (3–7 and 8–12 years). The intervention group received therapeutic play intervention, whereas the control group received standard care only. Participants were assessed on three occasions: before, during and after completion of the cast-removal procedure.

Outcome measures

Children’s anxiety level, emotional manifestation and heart rate. The satisfaction ratings of parents and cast technicians with respect to therapeutic play intervention were also examined.

Results

Findings suggested that therapeutic play assists children aged 3–7 to reduce anxiety levels with mean differences between the intervention and control group was −20.1 (95% CI −35.3 to −4.9; p=0.01). Overall, children (aged 3–7 and 8–12) in the intervention groups exhibited fewer negative emotional manifestations than the control group with a mean score difference −2.2 (95% CI −3.1 to −1.4; p<0.001). Parents and technicians in the intervention group also reported a higher level of satisfaction with the procedures than the control group with a mean score difference of 4.0 (95% CI −5.6 to 2.3; p<0.001) and 2.6 (95% CI 3.7 to 1.6; p<0.001), respectively.

Conclusion

Therapeutic play effectively reduces anxiety and negative emotional manifestations among children undergoing cast-removal procedures. The findings highlight the importance of integrating therapeutic play into standard care, in particular for children in younger age.

Trial registration number

ChiCTR-IOR-15006822; Pre-results.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study was one of the first randomised controlled trials to examine the effects of therapeutic play on children undergoing cast-removal procedures, building the evidence base of therapeutic play.

A major limitation was the lack of blinding of outcome assessor. Another limitation was recruiting children from a single clinical setting so that the generalisability of the findings may be restricted.

The strength of this study included employing both subjective and objective outcome measures to evaluate the impact of therapeutic play on the psychological state of a child.

Introduction

It is common for children to display stressed behaviour in clinical settings even during painless medical procedures such as cast removal (CR).1 2 The original injuries, sustained by the children, added to the unfamiliar environment and the equipment used during the procedures, are likely to provoke anxiety and fear in children of any age. The psychological burden on children makes the procedures difficult to perform effectively and efficiently, and may impose medical risks.1 3 For instance, an extreme case of death in a child having history of cardiomyopathy during the cast room procedure has been reported.1 Moreover, anxiety in the children also reduces parents’ satisfaction with the care provided.4 Various strategies such as the use of ear protection or musical lullabies have been used but have not proved very effective.5 6 Other interventions to reduce anxiety levels in children coping with CR procedures should be explored.

Therapeutic play is a set of structured activities designed according to the subject’s age, cognitive development and health-related issues, to promote emotional and physical well-being in hospitalised children.7 The therapeutic play activities may include scrapbooking, storytelling, doll demonstration and art activities. Li et al suggested that hospitalised children who engaged in therapeutic play exhibited fewer negative emotions and experienced lower levels of anxiety than those who did not.8 A recent systematic review of 14 articles found that therapeutic play was commonly employed for children undergoing invasive procedures, such as elective surgery, vaccination, blood collection or dental treatment in inpatient settings, with positive changes in the behaviour of those who participated in play sessions and a reduction in their anxieties.9 However, some of these studies were limited by the lack of random assignment of subjects into intervention or control groups. Besides, the efficacy of therapeutic play interventions is yet to be determined, as the studies reported were mainly based on clinical observation and most of the play manuals, which should have set out specific procedures to improve fidelity, were not fully described.10–12 Future study that adopt a robust randomised controlled design and delineate the scope of play procedures is clearly necessary.

Our literature search revealed no reports of prospective and randomised controlled studies on therapeutic play among children undergoing CR procedures, let alone among Hong Kong Chinese. Most importantly, the comprehensive value of therapeutic play in paediatric orthopaedic cast rooms—in their impact on the children, parents and medical institution as a whole—remains largely unexplored in the literature. This study aimed to examine the effectiveness of therapeutic play in reducing anxiety and negative emotional manifestations among children undergoing CR procedures. The satisfaction ratings of parents and cast technicians in respect of the CR procedures were also to be examined.

Theoretical framework

Lazarus and Folkman’s theory of stress and coping theory was used to guide this trial.13 They suggest that stress is a relationship between a person and the environment that the person finds taxing or exceeding resources. Coping is a constantly changing cognitive and behavioural effort to manage stressful situations. The two types of strategy used to cope with stress are problem-focused and emotional-focused coping. When individuals perceive that they cannot change the threatening situation, they will resort to emotion-focused coping.13 It is well known that CR procedures are stressful for children.1 2 Children likely feel stress and anxiety if they perceived a lack of control over the medical procedure.8 Therapeutic play works by helping children to prepare for the procedure and thereby assist them to regain a sense of self-control to cope with the stressful procedure.13 14 As a result, it is reasoned that children undergoing therapeutic play intervention will be more likely to cope with CR procedures and feel less stress and anxiety.

Methods

Design

A two-arm parallel randomised controlled trial was employed.

Setting

The study was conducted in the orthopaedic outpatient department (OPD) of a regional teaching hospital in Hong Kong, where the OPD cast room performs approximately 20 CR procedures monthly. The standard regimen in this OPD did not include therapeutic play intervention.

Participants

Children

Children and their accompanying parents who were waiting for the cast room procedure were invited to participate in the study if: (1) the child was 3–12 years of age and (2) the parents were able to speak Cantonese and read Chinese. Children were excluded if they: (1) had had a cast removed within the previous 3 months or (2) had neurological or developmental problems as shown on the medical record.

The rationale for selecting children aged 3–12 years was that the number of children having cast room procedure within this age range in Hong Kong was higher than for other age groups. According to Piaget’s (1963) theory of cognitive development, children from 3 to 7 belong to the same preoperational stage, while those between 8 and 12 belong to the concrete operational stage.15 Children in different age group are at the different stage of psychosocial development and likely respond to CR procedures and therapeutic play differently.16 Therefore, children were stratified according to their age group (3–7 and 8–12).

The sample size of the study was determined to detect an effect size of Cohen’s d=0.6 on the outcomes of anxiety level and emotional manifestation between the intervention and control groups with reference to previous therapeutic play studies17 18 for guiding the selection of a minimum detectable effect. By using the power analysis software GPower V.3.1, 45 subjects in each group were sufficient to detect an effect of at least 0.6 with 80% power at 5% level of significance. Taking into account of up to a 15% attrition rate and stratified the study by age, 53 children each would be recruited for the intervention and control groups per stratum by age (3–7 and 8–12 years).

Accompany parents and cast technicians

All accompany parents and cast technicians involved in the CR procedures were invited to assess their satisfaction for the procedures.

Randomisation

Eligible children undergoing the CR procedure were randomly allocated to the intervention or control groups in a 1:1 ratio. Randomisation was stratified by the two age groups, 3–7 and 8–12 years. Serially numbered opaque sealed envelopes containing the grouping identifier (intervention or control) for each age group were prepared in advance by an independent statistician using computer-generated random codes. The group allocation of the children recruited was assigned according to their ages and sequence of enrolment in the study, and the grouping identifier contained in the corresponding numbered envelopes.

Control group: standard care

Participants in the control group received standard care without therapeutic play intervention. Standard care included the nurse explaining why and what would be done and saying comforting and supportive words during the procedures.

Intervention group: therapeutic play

In addition to the standard care, children in the intervention group also received therapeutic play intervention. The interventions were conducted by an experienced and well-trained senior hospital play specialist (HPS). The HPS has more than 5 years of experience in delivering therapeutic play—including preparation play and distraction play—to children undergoing medical treatments in various units of hospitals. To ensure therapeutic play interventions were provided according to the children’s needs and psycho-cognitive development,15 16 the research team met with the HPS to set up the research protocol (online supplementary file). The content of the therapeutic play had two main components: preparation and distraction forms of play.19 The duration of intervention was about 30 min.

bmjopen-2017-021071supp001.pdf (573.6KB, pdf)

Preparation play

Preparation play was conducted before the CR procedure. A demonstration of the CR procedure was conducted using a doll. The demonstration included:

Showing a dummy circular-saw cast cutter with appropriate sound effects.

Playing with a doll and explaining how the cast was cut open by the circular saw.

Reassuring children that the saw would not cut their skin if they followed the instruction not to move.

Explaining that, when the cast was cut, the child might feel vibration or tingling, notice a certain warmth and see chalky dust flying.

Describing the use of spreaders and scissors to finish removing the cast.

Explaining how, after the cast was open, the skin might appear scaly and dirty and the limb feel a little stiff when first moved; also that the arm or leg might seem light because the cast had been heavy.

During the demonstration, the children were asked to touch and play with the doll and material, and role-play how they would respond to the procedure after the demonstration. The preparation play usually took 10–15 min to complete.

Distraction play

Throughout the CR procedure, support was given to children by introducing distraction play. The aim of the distraction play was to divert children’s attention away from the medical procedure. Methods of distraction included visual or auditory distraction, deep breathing exercises, tactile stimulation, counting/singing or other verbal interaction. The choice of method depended on the children’s choices.20 The parents’ presence and involvement were supported, and the children were praised for any act of successful self-control. The conclusion of the procedure was indicated by offering the children a reward (eg, stickers). The children did not know that they would receive reward in advance.

Primary outcome measures

Anxiety

Visual Analogue Scale

A Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) was used to assess the anxiety levels of children between 3 and 7. The VAS consists of a 10 cm horizontal line anchored by the words ‘not worried’ (low score) at one end and ‘very worried’ (high score) at the other, with drawings of different facial expressions spaced along the line. Children aged between 3 and 7 were asked to indicate their levels of anxiety by moving a pointer over the line. As children of 3 or 4 may have limited verbal expression abilities, their parents were also invited to rate the anxiety levels of their children. The VAS is a widely used scale which has been found to be a reliable and valid tool for measuring children’s subjective feelings.21

The short-form Chinese version of the State Anxiety Scale for Children

The Chinese version of the State Anxiety Scale for Children (CSAS-C) is a 10-item self-report scale measuring the anxiety levels of children aged 8–12 in busy clinical setting.17 It is a three-point Likert scale with total scores ranging from 10 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety levels.17 The psychometric properties of the short form have been tested and found to correlate highly with the scores on the full form (r=0.92), with good internal consistency (r=0.83) and convergent validity that differentiate the state anxiety of children in various situations. Factorial structure of the short form was also checked using exploratory and confirmatory analyses.22 The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale in this study was 0.80–0.88.23 24

Children’s Emotional Manifestation Scale

The emotional behaviour of children during CR procedures was documented by using the Children’s Emotional Manifestation Scale (CEMS), developed by Li and Lopez. It comprises five observable emotional forms of behaviour, categorised as ‘facial expression’, ‘vocalisation’, ‘activity’, ‘interaction’ and ‘level of cooperation’. The CEMS score is obtained by reviewing the descriptions of behaviour in each category and selecting the number that most closely represents the behaviour observed at the time the subject experiences the most distress. Each category is scored from 1 to 5. Observable forms of behaviour in each category of the CEMS are explained in detail with an operational definition, so that the observer, a research nurse in this study, using the scale has relatively clear-cut criteria for assessment. The sum of the numbers obtained for each category is the total score, which will be between 5 and 25, higher scores indicating the manifestation of more negative (distressed) emotional behaviour. The evaluation of the psychometric properties of the CEMS demonstrated adequate reliability and validity.25 The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale in this study was 0.86.23 24

Secondary outcome measures

Satisfaction scale for parent and cast technician

Two questionnaires in English, developed by Tyson et al,12 were adopted to measure parents’ and cast technicians’ satisfaction levels. The original questionnaire for parents is a 10-item scale to measure their satisfaction with the child life services. Each item is rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree, higher scores indicating higher levels of satisfaction. Example of the statement used is ‘My child’s emotional needs were met.’ The perception of the cast technician was examined by eight items, with each being rated on a scale from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree. Example of the statement used is ‘the child engaged in distraction.’ The researcher translated the questionnaire into Chinese, using the back-translation method recommended by Brislin.26 The translated version was reviewed by a panel of expert professionals for semantic and content equivalence. The scale level of semantic equivalence for the parents’ satisfaction and cast technician satisfaction was 95% and 92%, respectively, indicating that the translated version was a correct reflection of the original version.27 The Content Validity Index of the parent’s satisfaction level scale was 0.90 and cast technician’s satisfaction level scale was 0.94, indicating the content of the translated scale were equivalent to the original version. The Cronbach’s alpha of both scales in this study was 0.90.

Heart rate monitoring

A standard automatic heart rate monitoring machine, available in the study hospital, was used to measure children’s heart rates to assess their physiological responses to CR procedures. Children’s heart rates have been considered objective and definitive indicators for an indirect assessment of children’s anxiety levels in previous studies.28

Anxiety produced due to CR procedures likely manifested as an increase in heart rate in children.

A demographic sheet

The sociodemographic and clinical variables of parents and children were collected. The items for children include age, sex, reason for cast application and number of hospital admissions. The accompany parent’s age, sex, educational level and working status was also obtained. The cast technician’s demographic information, including age, sex and years of work experience was also collected by the research nurse.

Data collection

Children having their CR would be arranged to wait outside the cast room of the study OPD in a separate timeslot. They would be identified by a research nurse in the waiting area. Permission for a child meeting the recruitment criteria to participate was obtained from the accompanying parent. The research nurse conducted the interview with consenting parent–child pairs in a private room. The children in both groups were asked to indicate how anxious they were by completing either the VAS anxiety scale (for children between 3 and 7 years of age) or the short form of the CSAS-C (for children aged between 8 and 12).17 The research nurse obtained demographic and clinical data from the parents. She also asked the parents of children aged under 5 to use the VAS to indicate their child’s perceived anxiety level. Children’s heart rates were also monitored for 1 min at the end of the interview, using a standard automatic monitor.

According to the subject allocation scheme, children in the control group received standard care in CR room A, while the intervention group additionally received a therapeutic play intervention conducted by the HPS in CR room B. The parents and children were asked during the informed consent process not to discuss the purpose of the study with cast technicians in the cast room.

In the CR room, the research nurse took two 1 min recordings of the child’s heart rate: (1) when the cast technician started sawing the cast and (2) immediately after the cast had been removed. The research nurse then rated the child’s signs of distress from the time the saw touched the cast until the limb was free of it, by means of the CEMS.25 She also recorded the length of the whole CR procedure for each child. After the CR procedure, the research nurse asked the parents and the cast technician to fill in their respective satisfaction scales to reflect their perceptions of how the CR procedure had been delivered. The children were asked to recall their level of anxiety throughout the procedure by filling in either the VAS anxiety scale (for those between 3 and 7) or the short form of the CSAS-C (for those between 8 and 12).17 Parents were asked to rate the VAS scale for children under 5.

Data analysis

All data were analysed by means of IBM SPSS for Windows, V.22. Appropriate descriptive statistics were used to present the participants’ sociodemographics and outcome measurements. A generalised estimating equations (GEE) model was used to compare each of the outcome measures across time between the two groups. Specifically, the GEE model was used to estimate the mean change on each outcome between group with adjustment for the baseline group difference and accounting for autocorrelation of the outcome across time. All statistical analyses were two sided, with the level of significance set at 0.05.

Patient and public involvement

Development of the research question and outcome measures were based on the facts that many children reported anxiety during the CR procedures. Patients were not involved in the design, subject recruitment and conduct of the study. The findings will be disseminated to the study participants by publishing the study as an original article. A satisfaction survey was conducted involving the parents of the participants to assess whether the participants experienced any burden during the intervention.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the children and their families

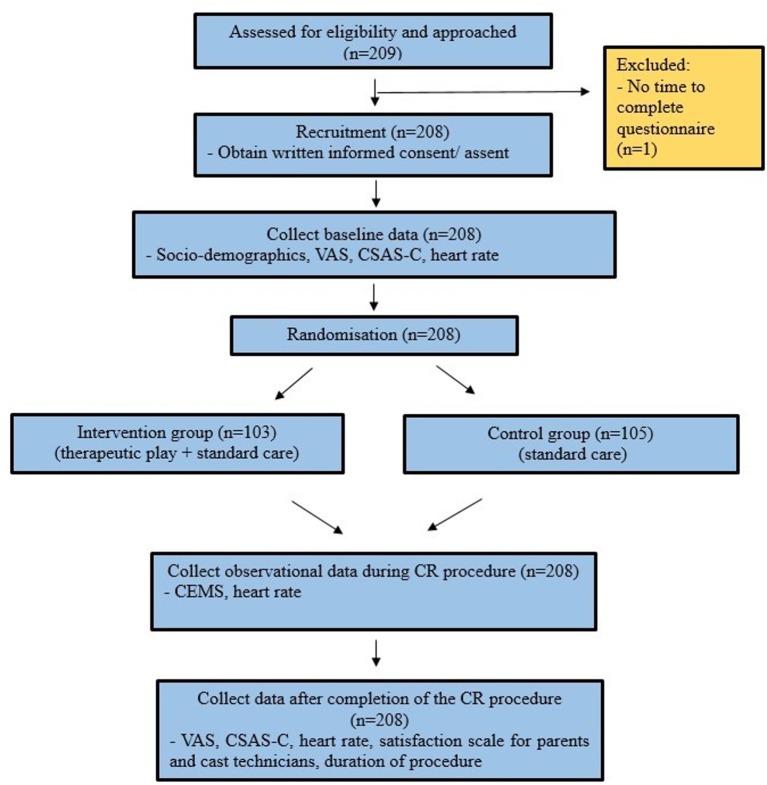

From August 2015 to January 2017, a total of 209 patients and their accompanying parents were screened and approached. However, one of them declined to participate in the study because they were in a hurry and had to leave the clinic at once after the procedure. Therefore, a total of 208 participants and their accompany parents were recruited. Of these, 105 were allocated to the control group and 103 to the intervention group (figure 1). Their mean ages were 7.7 (SD 3.0) and 7.5 (SD 2.9), respectively. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the two groups were comparable and are shown in table 1.

Figure 1.

The CONSORT diagram of this study. CEMS, Children’s Emotional Manifestation Scale; CR, cast removal; CSAS-C, Chinese version of the State Anxiety Scale for Children; CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Table 1.

Sociodemographics and clinical characteristics of the participants (n=208) and CR technicians (n=12)

| Characteristics | Control (n=105) | Intervention (n=103) |

| Children and their family | ||

| Age of the child (years)* | 7.7 (3.0) | 7.5 (2.9) |

| Age group | ||

| 3–7 years | 55 (52.4%) | 52 (50.5%) |

| 8–12 years | 50 (47.6%) | 51 (49.5%) |

| Sex of the child | ||

| Female | 37 (35.2%) | 36 (35.0%) |

| Male | 68 (64.8%) | 67 (65.0%) |

| Accompanied by | ||

| Mother only | 52 (49.5%) | 54 (52.4%) |

| Father only | 29 (27.6%) | 26 (25.2%) |

| Both parents | 14 (13.3%) | 10 (9.7%) |

| Mother/father together with other relatives | 6 (5.7%) | 6 (5.8%) |

| Other relatives | 4 (3.8%) | 7 (6.8%) |

| Highest education attainment of the accompanied family | ||

| Primary or below | 8 (7.6%) | 7 (6.8%) |

| Secondary | 63 (60.0%) | 64 (62.1%) |

| College or above | 34 (32.4%) | 32 (31.1%) |

| No of hospital admission |

||

| 0 | 38 (36.2%) | 31 (30.1%) |

| 1 | 30 (28.6%) | 36 (35.0%) |

| 2 | 25 (23.8%) | 14 (13.6%) |

| ≥3 | 12 (11.4%) | 22 (21.4%) |

| Type of casts | ||

| Arm long | 88 (83.8%) | 82 (79.6%) |

| Arm short | 6 (5.7%) | 7 (6.8%) |

| Leg long | 9 (8.6%) | 13 (12.6%) |

| Leg short | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (1.0%) |

| CR technician (n=12) | ||

| Sex | ||

| Female | 32 (30.5%) | 30 (29.1%) |

| Male | 73 (69.5%) | 73 (70.9%) |

| Age (years) | ||

| <30 | 16 (15.2%) | 9 (8.7%) |

| 30–40 | 34 (32.4%) | 39 (37.9%) |

| >40 | 55 (52.4%) | 55 (53.4%) |

| Years of experience | ||

| <2 | 14 (13.3%) | 9 (8.7%) |

| 2–5 | 47 (44.8%) | 41 (39.8%) |

| >5 | 44 (41.9%) | 53 (51.5%) |

Data of variables marked with * are presented as mean (SD), otherwise as frequency (%).

CR, cast removal.

Anxiety levels

Children aged between 3 and 7

The mean anxiety scores of children aged 3–7 in the intervention group as measured by VAS anxiety scale decreased from 35.4 to 27.6 after the CR procedures. By contrast, the mean anxiety levels of children who did not take part in therapeutic play increased from 34.0 to 46.3. The difference in mean changes between the two groups as estimated by the group by time interaction term by using GEE was −20.1 (95% CI −35.3 to −4.9; p=0.010) (table 2).

Table 2.

Outcome measures across time between the intervention and control groups among those children aged between 3 and 7 years (n=107)

| Control (n=55) | Intervention (n=52) | P values | Effect size (95% CI)* | |

| VAS anxiety scale (range: 0–100) | ||||

| T1 (before CR procedure) | 34.0 (30.0) | 35.4 (32.7) | ||

| T3 (after CR procedure) | 46.3 (37.3) | 27.6 (28.6) | 0.010† | 0.50 (0.11 to 0.88)‡ |

| Children’s Emotional Manifestation Scale (range: 5–25) | ||||

| T2 (during CR procedure)§ | 10.6 (4.7) | 8.1 (2.9) | 0.002¶ | 0.62 (0.23 to 1.01) |

| Heart rate (per minute) | ||||

| T1 (before CR procedure) | 88.7 (14.9) | 88.6 (14.5) | ||

| T2 (during CR procedure) | 95.8 (17.7) | 89.8 (16.6) | 0.081† | 0.33 (−0.05 to 0.71)‡ |

| T3 (after CR procedure) | 97.2 (15.6) | 90.0 (17.2) | 0.051† | 0.37 (−0.01 to 0.75)‡ |

| Parent satisfaction score (range: 10–50) | ||||

| T3 (after CR procedure) | 42.5 (6.7) | 47.3 (3.3) | <0.001¶ | 0.89 (0.49 to 1.28) |

| CR technician satisfaction score (range: 8–40) | ||||

| T3 (after CR procedure) | 31.5 (5.0) | 33.9 (3.7) | 0.007¶ | 0.54 (0.15 to 0.92) |

| Duration of procedure (min) | 4.8 (2.2) | 4.2 (2.0) | 0.126¶ | 0.30 (−0.08 to 0.68) |

Data of variables marked with † are presented as median (IQR), otherwise as mean (SD).

*Cohen’s d effect size.

†P value testing for differential change of heart rate at the underlying time point with respect to T1 by using GEE model.

‡The Cohen’s d effect size corresponds to the standardised mean difference of the mean changes at the underlying time point with respect to T1 between the intervention and control groups.

§Nature log-transformed before subjected to independent t-test.

¶Independent t-test.

CR, cast-removal; GEE, generalised estimating equations; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Accompanying parent(s) with children under 5 were invited to rate the anxiety levels of their children using VAS. The results showed that there were moderate to high correlations between the children and their parent’s rating before (r=0.36, 95% CI 0.0 to 0.65; p<0.05) and after the CR procedure (r=0.50, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.74; p<0.01).

Children aged between 8 and 12

The mean anxiety scores of children in the intervention group as measured by CSAS-C fell from 18.0 to 15.3, and in the control group from 17.4 to 15.9. The difference in mean changes between the two groups as estimated by using GEE was −1.1 (95% CI −2.8 to 0.5; p=0.171) (table 3).

Table 3.

Outcome measures across time between the intervention and control groups among those children aged between 8 and 12 years (n=101)

| Control (n=50) | Intervention (n=51) | P values | Effect size (95% CI)* | |

| State Anxiety Scale for Children (CSAS-C) (range: 10–30) | ||||

| T1 (before CR procedure) | 17.4 (4.0) | 18.0 (3.5) | ||

| T3 (after CR procedure) | 15.9 (4.7) | 15.3 (3.9) | 0.171† | 0.27 (−0.12 to 0.66)‡ |

| Children’s Emotional Manifestation Scale (range:5–25) | ||||

| T2 (during CR procedure)§ | 9.0 (2.6) | 7.0 (1.4) | <0.001¶ | 0.93 (0.51 to 1.33) |

| Heart rate (per minute) | ||||

| T1 (before CR procedure) | 86.3 (13.4) | 84.8 (12.6) | ||

| T2 (during CR procedure) | 96.2 (14.4) | 88.7 (14.5) | 0.037† | 0.41 (0.01 to 0.80)‡ |

| T3 (after CR procedure) | 89.9 (13.1) | 87.5 (13.8) | 0.720† | 0.07 (−0.32 to 0.46)‡ |

| Parent satisfaction score (range: 10–50) | ||||

| T3 (after CR procedure) | 42.8 (7.1) | 46.0 (6.5) | 0.020¶ | 0.47 (0.07 to 0.86) |

| CR technician satisfaction score (range: 8–40) | ||||

| T3 (after CR procedure) | 31.8 (3.5) | 34.8 (3.5) | <0.001¶ | 0.83 (0.42 to 1.24) |

| Duration of procedure (min) | 4.4 (2.2) | 3.9 (2.5) | 0.314¶ | 0.20 (−0.19 to 0.59) |

Data of variables marked with † are presented as median (IQR), otherwise as mean (SD).

*Cohen’s d effect size.

†P value testing for differential change at the underlying time point with respect to T1 by using GEE model.

‡The Cohen’s d effect size corresponds to the standardised mean difference of the mean changes at the underlying time point with respect to T1 between the intervention and control groups.

§Nature log-transformed before subjected to independent t-test.

¶Independent t-test.

CSAS-C, Chinese version of the State Anxiety Scale for Children; CR, cast removal; GEE, generalised estimating equation.

Emotional manifestation during CR procedures

The mean CMESs of children aged 3–7 and 8–12 in the intervention group were significantly lower than the control group (tables 2 and 3). Overall, the mean CMESs of the intervention group were 7.6 (SD 2.4) and of the control group 9.8 (SD 3.9) with a mean difference of −2.2 (95% CI −3.1 to −1.4; p<0.001), indicating that children in the intervention group, on average, exhibited fewer negative emotional manifestations during the CR procedures comparing with those children in the control group (table 4).

Table 4.

Outcome measures across time between the intervention and control groups

| Control | Intervention | P values | Effect size (95% CI)* | |

| Among all children (n=208) | ||||

| Children’s Emotional Manifestation Scale (range: 5–25) | (n=105) | (n=103) | ||

| T2 (during CR procedure)† | 9.8 (3.9) | 7.6 (2.4) | <0.001‡ | 0.69 (0.41 to 0.69) |

| Heart rate (per minute) | ||||

| T1 (before CR procedure) | 87.6 (14.2) | 86.7 (13.6) | ||

| T2 (during CR procedure) | 96.0 (16.2) | 89.3 (15.5) | 0.008§ | 0.36 (0.09 to 0.64)¶ |

| T3 (after CR procedure) | 93.7 (14.9) | 88.8 (15.6) | 0.070§ | 0.25 (−0.02 to 0.52)¶ |

| Parent satisfaction score (range: 10–50) | ||||

| T3 (after CR procedure) | 42.6 (6.9) | 46.6 (5.1) | <0.001‡ | 0.65 (0.38 to 0.93) |

| CR technician satisfaction score (range: 8–40) | ||||

| T3 (after CR procedure) | 31.7 (4.3) | 34.3 (3.6) | <0.001‡ | 0.66 (0.38 to 0.94) |

| Duration of procedure (min) | 4.6 (2.2) | 4.1 (2.3) | 0.072‡ | 0.25 (−0.02 to 0.52) |

Data of variables marked with † are presented as median (IQR), otherwise as mean (SD).

*Cohen’s d effect size.

†Nature log-transformed before subjected to independent t-test.

‡Independent t-test.

§P value testing for differential change at the underlying time point with respect to T1 by using GEE model.

¶The Cohen’s d effect size corresponds to the standardised mean difference of the mean changes at the underlying time point with respect to T1 between the intervention and control groups.

CR, cast removal; GEE, generalised estimating equation.

Changes in heart rate

No significant difference in heart rate was noted between the intervention and control group among children aged 3 and 7 years old (table 2). In contrast, significant difference was found before and during CR procedure between the intervention and control group among children aged 8 and 12 years old (table 3). Among all children, a trend of increasing heart rate was noted before and during the CR procedures for both groups. The mean heart rate of the intervention and control groups increased by 2.6 and 8.4 beats/min, respectively with a difference in mean changes between the two groups as estimated by using GEE was −5.9 (95% CI −10.3 to −1.5; p=0.008), indicating that the children in the intervention group might experience lower levels of anxiety than those in the control group (table 4).

Satisfaction levels of parents and cast technicians

Among all children, the satisfaction scores of parents in the intervention group (46.6, SD 5.1) were higher than the control group (42.6, SD 6.9) with a mean difference of 4.0 (95% CI 5.6 to 2.3; p<0.001). Similarly, the satisfaction scores of CR technician in the intervention group (34.3, SD 3.6) were higher than those in the control group (31.7, SD 4.3) with a mean difference of 2.6 (95% CI 3.7 to 1.6; p<0.001) (table 4).

Duration of procedure

Among all children, the mean time (in minutes) taken to perform the CR procedure was shorter in the intervention 4.1 (SD 2.3) than in the control groups 4.6 (SD 2.2) with a mean difference of −0.56 (95% CI −1.17 to 0.05; p=0.072) (table 2).

Discussion

This study expanded previous studies and examined the effects of a therapeutic play intervention on CR procedures in patients, parents and institutions. A randomised controlled design was employed such that the cause and effect relationships among variables could be established.27 Findings suggest that therapeutic play effectively assists children aged 3–7 to cope with stressful CR procedures and reduces their anxiety levels. Overall, children who received the intervention exhibited significantly fewer negative emotional manifestations than those who did not.

Most children in this study presented some degree of anxiety before the procedures, the use of a saw and the fluctuating level of high-frequency noise probably accounting for most of the anxiety.1 29 Previous studies employed ear protection5 or lullaby-type music6 to reduce anxiety in children during CR, while heart rate and mean arterial blood pressure were used as physiological outcome indicators of anxiety, respectively. However, no significant difference was noted in these parameters in either study.

The positive results of the present study are further supported by the fact that the mean increase in heart rates before and during the procedure was lower in the intervention than in the control group. A possible explanation may be that the therapeutic play assisted children to cope with an unfamiliar procedure. During the play session, the HPS explained and simulated the CR procedures, which allowed the children to understand them. As the children were familiarised with the procedure, they would expect it to generate noise but not pain. These preparations assisted the children in such a way that they had an enhanced sense of control over the procedure, minimising the adverse effects of the experience.6 As suitable and age-appropriate distraction were provided to the intervention group, the children’s attention was diverted from the anxiety-provoking procedure to playful interaction. They, therefore, exhibited less negative emotional behaviour. However, children without any distraction might have focused on the whole procedure and thus exhibited more negative emotions and increased anxiety levels, even after it was all over.

Nevertheless, although children of 8–12 in the intervention group had larger reductions in their anxiety scores than those in the control group after the procedure, the difference between the groups was non-significant. The results were in conflict with those of a previous study suggesting that older hospitalised children benefit more from the play intervention.21 30 One possible explanation for the non-significant findings is that older children have a better understanding of CR procedures than younger children. According to Piaget,15 children of 8–12 can mentally manipulate information to solve problems. As they may have obtained information about the CR procedure from other sources, such as books, the internet or friends, they might feel less anxious about the forthcoming procedure. Moreover, compared with younger children, older children probably have better coping strategies and better control of their emotions, even in stressful situations. Nevertheless, further study is needed to determine other effective methods for children at this developmental stage.

Consistent with a previous study,31 the result indicated that parents of children in the intervention group were more satisfied with the care and play intervention than those of children receiving standard care only. The satisfaction of parents in the intervention group is likely to have increased because they also experienced the positive influence of play on their children, particularly the reduction in anxiety and improved cooperation with the procedure.32 In fact, parental perception played an important role on child’s coping with various conditions such as cancer or other medical procedures.33 The positive correlations in the VAS ratings of children under 5 further suggested that parents also perceived their children to be less anxious after the intervention. However, further study could also include self-report questionnaire on satisfaction and examine the mediating role of parents play in the distraction intervention.

Some cast technicians might have concerns that the CR procedures would be impeded and prolonged because the play intervention was implemented at the same time. However, the findings suggest that the duration of the entire procedure was shorter in the intervention than in the control group, although the differences were non-significant. Nevertheless, the duration in the intervention group did decrease, probably because the children were psychologically prepared and were thus more cooperative. In fact, children who are less anxious are easier to manage in clinical situations,34 which may account for the increased satisfaction of CR technicians in procedures assisted by HPS.

Limitations

The results of the current study should be interpreted in the light of several limitations. First, children were recruited from a single clinical setting. The generalisability of the findings may therefore be restricted. Second, neither patients nor outcome assessors were blinded to the study. However, because of the very nature of the intervention, blinding of patients and outcome assessors would have been difficult. Although children are unlikely to change their behaviour even when they know they are participating in a certain intervention,9 however, lack of blinding may contribute to an importance source of bias because the assessors know the group allocation of children which likely affect their ratings of children’s emotional manifestation during the CR procedures. Nevertheless, different strategies were employed to minimise the potential bias. For example, children were assigned to different cast rooms and isolated from other patients at the time of the intervention, regardless of whether or not they were randomised to the play intervention group. Also, subjective and objective outcome measures were used to evaluate the impact of therapeutic play on the psychological state of a child. Finally, there might be other factors that affect children’s anxiety level and play predisposition such as children’ coping styles or temperament, or parent’s anxiety level and symptomatology towards CR procedure. Future study should take these factors into account and consider to include the assessment of children’s coping style or parents’ anxiety level as well.

Conclusions

This study confirms the findings of previous work that children experience some degree of anxiety and exhibit negative emotional manifestations during medical procedures. The consequences of stress appear to be substantial, and thus the importance of assisting children to cope effectively with it and reduce its impact is highlighted. A gap in the literature is addressed by providing empirical evidence on the benefits of therapeutic play for children, family and medical institution during CR procedures. The findings show that a play intervention effectively reduces anxiety levels and negative emotional manifestations among children undergoing CR procedures. Such positive outcomes also translate into an improvement in the satisfaction levels of parents and CR technicians with the procedures. Play is universal and similar intervention can be adopted in other settings or medical procedures. It may also adopt to reduce anxiety and improve motor abilities of children that underwent invasive procedures.35 The findings highlight the importance of providing and integrating therapeutic play into standard care. Such an intervention ensures that holistic and quality care is provided to ease the psychological burden of the patients. Furthermore, it contributes to improve patient care, satisfaction and overall experience of children and their families.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude for the generous support of Kuenflower Management Inc. (in honour of Kwong Sik Kwan and Kwong Hui May Kuen) to the UBS Optimus Foundation in sponsorship for this project.

Footnotes

Contributors: WYI and BKWN conceived and designed the study. CLW and WYI obtained ethical approval. BMCK supervised data collection. CLW supervised the data analysis and wrote the paper. KCC provided statistical support and analysed the data. BMCK and CWHC helped revising the manuscript. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This study was supported by the Playright Children’s Play Association.

Disclaimer: The funding agencies are not responsible for the opinions presented in the manuscript. The funding bodies had no influence on the conduct of the study or the interpretation of the results.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong—New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee (2015.005-T).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Not additional data are available.

References

- 1. Katz K, Fogelman R, Attias J, et al. Anxiety reaction in children during removal of their plaster cast with a saw. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001;83:388–90. 10.1302/0301-620X.83B3.10487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mahan ST, Harris MS, Lierhaus AM, et al. Noise reduction to reduce patient anxiety during cast removal: can we decrease patient anxiety with cast removal by wearing noise reduction headphones during cast saw use? Orthop Nurs 2017;36:271–8. 10.1097/NOR.0000000000000365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sanders MB, Starr AJ, Frawley WH, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in children recovering from minor orthopaedic injury and treatment. J Orthop Trauma 2005;19:623–8. 10.1097/01.bot.0000174709.95732.1b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. He HG, Zhu LX, Chan WC, et al. A mixed-method study of effects of a therapeutic play intervention for children on parental anxiety and parents' perceptions of the intervention. J Adv Nurs 2015;71:1539–51. 10.1111/jan.12623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carmichael KD, Westmoreland J. Effectiveness of ear protection in reducing anxiety during cast removal in children. Am J Orthop 2005;34:43–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu RW, Mehta P, Fortuna S, et al. A randomized prospective study of music therapy for reducing anxiety during cast room procedures. J Pediatr Orthop 2007;27:831–3. 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181558a4e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vessey JA, Mahon MM. Therapeutic play and the hospitalized child. J Pediatr Nurs 1990;5:328–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li WHC, Chung JOK, Ho KY, et al. Play interventions to reduce anxiety and negative emotions in hospitalized children. BMC Pediatr 2016;16:16–36. 10.1186/s12887-016-0570-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Silva RD, Austregésilo SC, Ithamar L, et al. Therapeutic play to prepare children for invasive procedures: a systematic review. J Pediatr 2017;93:6–16. 10.1016/j.jped.2016.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brewer S, Gleditsch SL, Syblik D, et al. Pediatric anxiety: child life intervention in day surgery. J Pediatr Nurs 2006;21:13–22. 10.1016/j.pedn.2005.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stevenson MD, Bivins CM, O’Brien K, et al. Child life intervention during angiocatheter insertion in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2005;21:712–8. 10.1097/01.pec.0000186423.84764.5a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tyson ME, Bohl DD, Blickman JG. A randomized controlled trial: child life services in paediatric imaging. Springer-Verlag 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li HC, Chung OK, Ho KY, et al. Coping strategies used by children hospitalized with cancer: an exploratory study. Psychooncology 2011;20:969–76. 10.1002/pon.1805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Piaget J. The origins of intelligence in children. New York: Norton, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Erikson E. Childhood and society. 2nd Edn New York: Norton & Company, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li HC, Lopez V. Development and validation of a short form of the Chinese version of the State Anxiety Scale for Children. Int J Nurs Stud 2007;44:566–73. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. He HG, Zhu L, Chan SW, et al. Therapeutic play intervention on children’s perioperative anxiety, negative emotional manifestation and postoperative pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs 2015;71:1032–43. 10.1111/jan.12608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hasenfuss E, Franceschi A. Collaboration of nursing and child life: a palette of professional practice. J Pediatr Nurs 2003;18:359–65. 10.1016/S0882-5963(03)00158-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Doellman D. Pharmacological versus nonpharmacological techniques in reducing venipuncture psychological trauma in pediatric patients. J Infus Nurs 2003;26:103–9. 10.1097/00129804-200303000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bringuier S, Dadure C, Raux O, et al. The perioperative validity of the visual analog anxiety scale in children: a discriminant and useful instrument in routine clinical practice to optimize postoperative pain management. Anesth Analg 2009;109:737–44. 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181af00e4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li HC, Wong ML, Lopez V. Factorial structure of the Chinese version of the State Anxiety Scale for Children (short form). J Clin Nurs 2008;17:1762–70. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02284.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wong CL, Ip WY, Chan CWH, et al. The stress-reducing effects of therapeutic play on children undergoing cast removal procedure Poster session presented at the hospital authority convention. Hong Kong, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wong CL. The best partner in a stressful medical procedure: play. Paper presented at the imagining the future: community innovation and social resilience in Asia. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li HC, Lopez V. Children’s Emotional manifestation scale: development and testing. J Clin Nurs 2005;14:223–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01031.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brislin RW. The wording and translation of research instrument : Lonner WJ, Berry JW, Field methods in cross-cultural research. Beverly Hills, CA: Stage, 1986:137–64. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Polit DF, Beck CT. Essentials of nursing research: appraising evidence for nursing practice. 8th edn Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Panda N, Bajaj A, Pershad D, et al. Pre-operative anxiety. Effect of early or late position on the operating list. Anaesthesia 1996;51:344–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chan CW, Choi KC, Chien WT, et al. Health-related quality-of-life and psychological distress of young adult survivors of childhood cancer in Hong Kong. Psychooncology 2014;23:229–36. 10.1002/pon.3396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ziegler DB, Prior MM. Preparation for surgery and adjustment to hospitalization. Nurs Clin North Am 1994;29:655–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schlechter JA, Avik AL, DeMello S. Is there a role for a child life specialist during orthopedic cast room procedures? A prospective-randomized assessment. J Pediatr Orthop B 2017;26:575–9. 10.1097/BPB.0000000000000310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. William Li HC, Lopez V, Lee TL. Effects of preoperative therapeutic play on outcomes of school-age children undergoing day surgery. Res Nurs Health 2007;30:320–32. 10.1002/nur.20191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tremolada M, Bonichini S, Basso G, et al. Coping with pain in children with leukemia. Int J Cancer Res Pre 2015;8:451–66. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schreiber KM, Cunningham SJ, Kunkov S, et al. The association of preprocedural anxiety and the success of procedural sedation in children. Am J Emerg Med 2006;24:397–401. 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Taverna L, Tremolada M, Bonichini S, et al. Motor skill delays in pre-school children with leukemia one year after treatment: Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation therapy as an important risk factor. PLoS One 2017;12:e0186787 10.1371/journal.pone.0186787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-021071supp001.pdf (573.6KB, pdf)