Abstract

Objectives

In response to a call from the American Heart Association to more clearly identify the demographic factors associated with sedentary behaviours, this study aimed to identify the hierarchy of demographic characteristics associated with the sedentary behaviours of television viewing, recreational computer use and driving.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of baseline data collected as part of the UK Biobank. The UK Biobank is a population cohort recruited from 22 centres across the UK. Participants aged between 37 and 73 years were recruited between 2006 and 2010.

Methods

Decision tree models were generated for the sedentary behaviour outcomes of hours/day spent television viewing, recreational computer use and all driving; a sum of time spent in these sedentary behaviours (‘overall’) was computed. Age, sex, race, college attendance, employment, shift-work, urban versus rural residence as well as physical activity were considered as predictors.

Results

The analytic sample comprised 415 666 adults who were mostly female (54.2%), white (95.2%), non-college attendee (64.5%), employed (61.7%), lived in an urban centre (85.5%), with a mean age of 56.6 (SD=8.1) years. Television viewing was most common sedentary behaviour (2.7 hour/day vs 1.1 for recreational computer use and 1.0 for all driving). Males (tier 1), who did not attend college (tier 2) were the highest risk group for overall sedentary time. Adults with no college attendance (tier 1) and were retired (tier 2) were the most high-risk demographic group for television viewing. College attendees (tier 1) were highest risk for recreational computer use. Adults who were employed (tier 1), male (tier 2) and did not attend college (tier 3) were most at risk for driving

Conclusions

Daily time spent in different sedentary behaviours varies by sex, employment status and college attendance status. The development of targeted interventions to reduce sedentary behaviour in different demographic subgroups is needed.

Keywords: epidemiology, preventive medicine, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study uses a large population cohort of-middle age adults from the UK.

Hierarchical decision tree modelling is used to identify a demographic risk profile for sedentary behaviours.

The study relies on self-report, cross-sectional data.

Work-based sedentary behaviour is not considered.

Introduction

Sedentary behaviour is defined as any waking activity characterised by an energy expenditure of <1.5 metabolic equivalents (METs) performed in a sitting or reclining posture.1 2 High levels of sedentary behaviour have been associated with cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality, even after adjustment for time spent in light and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity.3–5 For example, participants who reported more than 10 hours of riding in a car per week had a 50% greater risk of cardiovascular disease mortality than those riding less than 4 hours, even after adjustment for physical activity and other cardiovascular risk factors.6 Given that interventions to address other, ‘established’ behavioural cardiovascular risk factors such physical inactivity, tobacco use and poor dietary behaviours may have limited long-term efficacy,7 there is an opportunity for sedentariness, as a common modifiable behaviour, to be a potentially potent intervention target with which to ameliorate cardiovascular disease risk across time.

In addition to quantifying the independent relationship between sedentary behaviour time with disease outcomes, research has also been dedicated to identifying predictors of sedentary time.8 Expected outcomes of this work is the capacity to define subgroups that are associated with higher levels of sedentary behaviour, and in turn, high-priority intervention targets. Examinations into demographic variables associated with sedentary behaviour has yielded mixed evidence.1 For example, while studies have generally shown older adults (>60 years) to be more sedentary than younger adults,9–11 there is less consensus around other demographic variables. Some studies show that males are more sedentary,12 13 while others show that, on average, females are,14 and still others report no gender differences in sedentary time.15 16 Examinations of racial differences in sedentary time also yield inconsistent results, with some studies showing Black/African American adults to be more sedentary,17 others show no racial differences18 and still others show Non-Hispanic Whites to be more sedentary than other racial groups examined.10 Increased sitting time in adults with higher levels of education have been shown by some studies,8 13 19 but not all.20

There are several possible reasons to account for the inconsistencies in the literature examining demographic correlates and determinants of sedentary time. One reason is the range of self-report tools used to assess sedentary behaviour in smaller community samples that may yield different results.21 Another reason is that many studies only report on one form of sedentary behaviour (ie, television viewing). Studies comparing different forms of sedentary behaviour may therefore identify different relationships with demographic factors. In addition, the consideration of individual demographic correlates and determinants of sedentary time22 may oversimplify or not fully consider the hierarchy of demographic factors that combine to present a high-risk profile for different forms of sedentary behaviours.

To address these limitations and to respond to a recent call in the literature to more clearly define the demographic determinants of sedentary behaviour,1 this study used Classification and Regression Trees (CART) decision tree modeling23 to identify the hierarchy of demographic characteristics that best differentiate between high and low engagement in the sedentary behaviours of television viewing, recreational computer use and driving in a population sample (eg, Roda et al 2016).24

Methods

Study design and participants

Data for this analysis were collected by the UK Biobank prospective cohort study that began in 2005. Using patient registers from the UK National Health Service (NHS), adults aged 40–69 years who live within a 10 mile radius of one of the UK Biobank’s 35 assessment centres were invited to participate. At a baseline visit, participants provided written informed consent and completed a touch screen questionnaire that assessed sociodemographic, lifestyle and health behaviour variables. Between 2006 and 2010, 502 656 eligible and consenting adults provided baseline data. More expansive details about the rationale, design and survey methods for UK Biobank have been described elsewhere.25 Study procedures were approved by the UK Biobank Institutional Review Board. Study participants were not involved with the design of the study or the recruitment of cohort members.

Measures

The outcome of interest was sedentary behaviour. Participants self-reported how many hours per day they spent watching television, using a computer for recreation and driving (recreational and work-related) on a typical day. For the purposes of this analysis, an ‘overall’ sedentary time variable was generated by summing the time spent in each of these sedentary activities. Participants reporting over 16 hours of sedentary time (n=974), were recoded to 16 hours.26

The predictors of interest were the demographic variables of age (continuous), sex (male, female), race (White, Asian/Asian British/Chinese, Black/Black British, mixed/other, Do not know/prefer not to answer), attended college (yes, no, prefer not to answer), employment (employed, unemployed or retired), shift-work (yes, no, do not know/prefer not to answer) and urban versus rural residence (urban, rural, no postal code provided).

Physical activity as measured by excess MET hours was considered as a predictor in decision tree models given the demonstrated relationship between physical activity and sedentary behaviour.27 Participants self-reported how many days in a typical week, and for how many minutes in each of those days, they engaged in walking, moderate and vigorous activity for 10 or more minutes. For each of the three categories of activity, values of >1260 min per week (equivalent to an average of 3 hours per day) were truncated at 1260, while values of <10 min was recoded to 0.28 Excess MET values of 2.3 for walking, 3.0 for moderate physical activity and 7.0 for vigorous physical activity were multiplied with the time in hours spent in each activity, to generate Excess MET/hours for each category.29

Generation of analytic sample

Baseline data from 502 623 participants were obtained. Participants with overall sedentary time greater than 24 hours (n=76) and those who withdrew from the study (n=4) were initially excluded, leaving 502 543 participants. Further, participants with missing data for any of the study variables were excluded (n=86 877), leaving 415 666 participants in the final analytic sample. Although significant differences between participants with complete and incomplete data were observed for all study variables (table 1), this is due to our large sample size and high power. As a result, Cohen’s d were calculated and were deemed either very small (<0.20) or small (0.20–0.49) in size for all study variables, indicating negligible differences between participants with complete and incomplete data.30 Thus, all analyses in this study reflect data from participants with complete information for all study variables.

Table 1.

Study sample characteristics

| Variable | Complete data (n=415 666) |

Incomplete data (n=86 877) |

P values* | d |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 56.64 (8.14) | 56.01 (7.85) | <0.0001 | 0.08 |

| Sex, n (%) | <0.0001 | 0.02 | ||

| Female | 225 456 (54.2%) | 47 979 (55.2%) | ||

| Male | 190 210 (45.8%) | 38 898 (44.8%) | ||

| Race, n (%) | <0.0001 | 0.15 | ||

| Mixed/Other | 5284 (1.3%) | 2233 (2.6%) | ||

| Asian | 8267 (2.0%) | 3184 (3.7%) | ||

| Black | 5439 (1.3%) | 2618 (3.0%) | ||

| White | 395 506 (95.2%) | 77 235 (88.9%) | ||

| Do not know/Prefer not to answer | 1170 (0.3%) | 1607 (1.9%) | ||

| Education, n (%) | <0.0001 | 0.19 | ||

| College | 144 599 (34.8%) | 16 585 (19.1%) | ||

| No college | 268 275 (64.5%) | 62 947 (72.5%) | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 2792 (0.7%) | 2699 (3.1%) | ||

| Missing | 0 (0.00%) | 4646 (5.4%) | ||

| Employment status, n (%) | <0.0001 | 0.26 | ||

| Employed | 256 588 (61.7%) | 30 593 (35.2%) | ||

| Unemployed | 12 079 (2.9%) | 1780 (2.1%) | ||

| Retired | 146 999 (35.4%) | 19 998 (23.0%) | ||

| None of the above/Prefer not to answer | 0 (0.00%) | 4886 (5.6%) | ||

| Missing | 0 (0.00%) | 29 620 (34.1%) | ||

| Shift work, n (%) | <0.0001 | 0.14 | ||

| Yes | 42 285 (10.2%) | 7266 (8.4%) | ||

| No | 372 902 (89.7%) | 44 865 (51.6%) | ||

| Do not know/Prefer not to answer | 479 (0.1%) | 240 (0.3%) | ||

| Missing | 0 (0.00%) | 34 506 (39.7%) | ||

| Residence, n (%) | <0.0001 | 0.13 | ||

| Urban | 355 222 (85.5%) | 73 587 (84.7%) | ||

| Rural | 60 429 (14.5%) | 8232 (9.5%) | ||

| No postal code provided | 15 (0.00%) | 3 (0.00%) | ||

| Missing | 0 (0.00%) | 5055 (5.8%) | ||

| Season of assessment, n (%) | <0.0001 | 0.04 | ||

| Fall (September–November) | 100 142 (24.1%) | 19 257 (22.2%) | ||

| Winter (December–February) | 86 848 (20.9%) | 17 815 (20.5%) | ||

| Spring (March–May) | 119 536 (28.8%) | 26 949 (31.0%) | ||

| Summer (June–August) | 109 140 (26.3%) | 22 853 (26.3%) | ||

| Missing | 0 (0.00%) | 3 (0.00%) | ||

| Mean TV Use, hours/day (SD) | 2.69 (1.6) | 3.35 (2.1) | <0.0001 | 0.40 |

| Mean computer use, hours/day (SD) | 1.08 (1.4) | 1.10 (1.5) | 0.0009 | 0.01 |

| Mean driving time, hours/day (SD) | 0.99 (1.2) | 0.89 (1.3) | <0.0001 | 0.08 |

| Mean overall sedentary behaviour, hours/day (SD) | 4.76 (2.3) | 4.98 (2.8) | <0.0001 | 0.09 |

| Mean total physical activity, excess MET-hours/week (SD) | 31.78 (33.0) | 27.65 (32.0) | <0.0001 | 0.13 |

| Categorised total physical activity, n (%) | <0.0001 | 0.18 | ||

| Low activity (<10 excess MET-hours/week) | 109 215 (26.3%) | 13 809 (15.9%) | ||

| Moderate activity (10–49.9 excess MET-hours/week) | 223 597 (53.8%) | 19 142 (22.0%) | ||

| High activity (≥50 excess MET-hours/week) | 82 854 (19.9%) | 6436 (7.4%) | ||

| Missing | 0 (0.00%) | 47 490 (54.7%) |

Column percentages do not always add up to 100% because of rounding.

*P values based on χ² tests for categorical variables and two-sample t-tests for continuous variables.

d, Cohen’s d effect size; MET, metabolic equivalents; n, frequency.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated to characterise all variables. Frequencies and percentages were used to describe categorical variables. Since all continuous variables were normally distributed, means and SD were used to describe these variables. To examine hierarchical clusters of demographic variables associated with each sedentary outcome, a separate decision tree model that included all demographic predictors and physical activity were generated for each of the study outcomes. Specifically, the CART growing method was used for all decision tree analyses, which split the data into binary segments that were as homogeneous as possible with respect to the outcome until no predictors could improve the homogeneity of the nodes given a complexity parameter of 0.01 for all decision tree models.23 24 In this study, the between-group sum of squares (or R-squared) is maximised in splitting nodes and pruning the tree. If the increase in R-squared is less than the complexity parameter, splitting will stop. The analytic sample was randomly split into 60% training (n=249 399) and 40% testing sets (n=166 267). Decision trees were constructed using the training data and were validated using 10-fold cross validation. The performance of the decision trees was then evaluated using the testing data. R-squared for both the training and testing data were reported. Descriptive statistics were generated using SAS V.9.4 (SAS, Cary, North Carolina, USA) and decision tree analyses were conducted using the rpart package in R V.3.4.3.

Patient and public involvement

The current study is a secondary analysis of the UK Biobank. Study design and development was not informed by patient input. We are not aware of the UK Biobank plans for dissemination of results to study participants.

Results

Participant characteristics

The analytic sample comprised 415 666 adults. Of these, 54.2% were female, 95.2% were White and 64.5% reported that they did not attend college. Six out of 10 (61.7%) respondents were employed (full time or part time) while 10.2% reported being shift workers. Most of the sample resided in urban areas (85.5%). In terms of sedentary behaviours, mean daily hours of television viewing was 2.7 (SD=1.6); computer use was 1.1 (SD=1.4), while mean driving time was 1.0 (SD=1.2) hours per day. Overall mean sedentary time was 4.8 hours per day (SD=2.3). One in five adults (19.9%) reported high activity (≥50 excess MET hours/week), 53.8% reported moderate activity (10–49.9 excess MET hours/week), while 26.3% reported low levels of physical activity (<10 excess MET hours/week) (table 1).

Demographic variables associated with overall sedentary behaviour

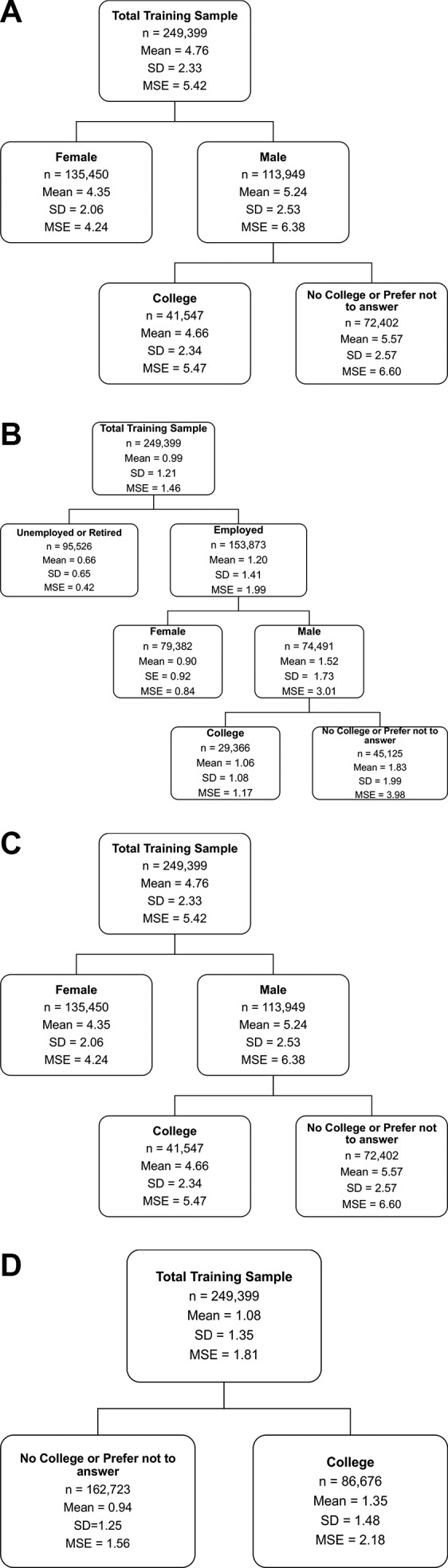

In the decision tree model of overall hours of sedentary behaviour each day, being male (tier 1) and not attending college or responding ‘prefer not to answer’ (tier 2) distinguished the demographic profile with the highest mean daily hours of sedentary behaviours (mean [M]=5.57, SD=2.57, mean squared error (MSE)=6.60) vs the 4.35 hours (SD=2.06, MSE=4.24) recorded by female participants (figure 1A). R-squared for both the training and testing samples was 0.05.

Figure 1.

(A) Decision tree model results for overall sedentary time using training set (n=249 399). (B) Decision tree models results for daily hours of television viewing using training set (n=249 399).(C) Decision tree models results for daily hours of recreational computer use using training set (n=249 399). (D) Decision tree models results for daily hours of all driving using training set (n=249 399). MSE, mean squared error.

Demographic variables associated with television use

In the decision tree model of daily television viewing, not attending college or responding ‘prefer not to answer’ (tier 1) and being retired (tier 2) was the demographic risk profile for those that accumulated the highest mean daily hours of television viewing (M=3.49, SD=1.65, MSE=2.72) vs the 1.92 (SD=1.24, MSE=1.53) mean hours (reported by college attendees who were employed or unemployed) (figure 1B). R-squared for both the training and testing samples was 0.13.

Demographic variables associated with recreational computer use

In the decision tree model of daily recreational computer use, only college education emerged as a significant distinguishing factor with college graduates averaging 1.35 hours per day (SD=1.48, MSE=2.18) vs the 0.94 hours (SD=1.25, MSE=1.56) recorded by non-college graduates and those responding ‘prefer not to answer’ (figure 1C). R-squared for both the training and testing samples was 0.02.

Demographic variables associated with driving

In the decision tree model of all driving time, being employed (tier 1), male (tier 2) and not attending college or responding ‘prefer not to answer’ (tier 3) was the demographic profile that distinguished the highest mean daily hours of driving (M=1.83, SD=1.99, MSE=3.98) vs the 0.90 (SD=0.92, MSE=0.84) mean hours reported by employed, female participants (figure 1D). R-squared for both the training and testing samples was 0.12.

Discussion

Sedentary behaviour is a common behaviour, increasingly being recognised as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease.1 To advance the development of targeted interventions to reduce sedentary behaviours,1 the current study used decision tree modelling to identify the hierarchy of demographic characteristics that most related to different sedentary behaviours. The key findings from this population study were that males with no college education accrued the most overall sedentary time. Adults with no college education and who were retired (vs employed or unemployed) reported the highest mean for television viewing, adults with a college education reported more daily hours of recreational computer use, while employed males, who did not attend college reported more hours per day of all driving. Together, these results indicate that sex, college attendance and employment status are key demographic correlates of sedentary behaviour and that the demographic risk-profile varies for different sedentary behaviours.

Decision tree modelling of overall sedentary time showed that males with no college education were the highest risk group for sedentary behaviour with a mean of 5.57 hours of sedentary time per day vs 4.35 hours reported by females (see figure 1A). These data may go towards clarifying a body of mixed evidence in which some studies have shown males to be more sedentary than females,12 females to be more sedentary than males14 or no gender difference at all.31 Likewise, low educational attainment has been associated with greater sedentary time,32 while higher education has been associated with sitting >7.5 hours per day.8

One reason for the inconsistent findings in the association between education levels and sedentary behaviour may be that sitting at work for >7.5 hours per day is more common in managerial-level desk jobs that are more characteristic of higher education subgroups.33 The current study queried about ‘recreational’ sedentary behaviours (ie, recreational computer use). Thus, these data underscore how demographic risk profiles for work, and non-work, based sedentary behaviours may be different, and the importance of considering work and non-work-related sedentary time separately.

When the individual sedentary behaviours of television viewing, recreational computer use, and all driving were considered, television viewing emerged as the most time-absorbing sedentary behaviour. This converges with previous literature showing television viewing to account for at least 50% of total sitting time34 as well as a robust marker of overall sedentary time in women.35 That adults who had not attended college and were retired were the highest risk group for television viewing by accruing a full 1.57 more hours per day of television time than those who went to college and were employed or unemployed (figure 1B) is somewhat of a departure from previous work. Specifically, low educational attainment has consistently been associated with lower levels of overall sedentary time,36 most likely because adults with lower levels of education are more likely to have more active, less-sedentary occupations.37 These data extend this work by showing that as one form of sedentary behaviour, television viewing is greater in those without a college degree. As expected, older, retired, adults reported more television viewing; together, these data give a novel risk profile for television viewing.

The demographic risk profiles for recreational computer use and driving time could be related to employment type. For example, as might be expected, recreational computer use time was higher in those with a college education versus those without.38 That employed males who did not attend college were the high-risk demographic group for increased daily driving time could be related to blue-collar service jobs (ie, plumber, electrician) that require driving and no college education.

These data have several implications for clinical and population health efforts. First, that the mean hours per day of non-work specific sedentary behaviour was 4.60 indicates that a considerable proportion of adult disposable time is dedicated to being sedentary. Given that the sedentary time queried in this study was not work-specific, this time may be more under the control of the individual and more amenable to change. Changes such as replacing sedentary time with heart-health enhancing behaviours including light to moderate physical activity and/or achieving adequate sleep duration, can reduce mortality and improve cardiovascular markers.39 40

Second, previous data have shown that independent of physical activity and other cardiovascular disease events, every additional hour of sedentary time increases the odds of an incident cardiovascular disease event by 1.06.41 In the current study, where males with no college education accrued 1.28 more hours of overall sedentary time each day (vs females), this magnitude of difference is considerable, especially when one considers that males have a higher age-standardised mortality rate in cardiovascular disease (205.2 per 100 000) than females (129.0 per 100 000)42 and that in higher-income countries, lower educational attainment is associated with higher rates of cardiovascular disease events.43 Given that physical activity was not retained by any of the decision tree models in this study as a key correlate, these data underscore the independence of physical activity and sedentary behaviours as independent constructs44 and support the need to reduce sedentary time in the high-risk demographic groups identified here as a strategy to ameliorate cardiovascular disease.

Third, each of the sedentary behaviours studied emerged with a different high-risk demographic profile. This finding suggests that ‘sedentary behaviour’ is not a homogeneous behaviour and that different sedentary behaviours may have different determinants. These data also suggest that reducing sedentary time in one demographic group may require focusing on a specific form of sedentary behaviour. For example, in retired adults who did not attend college, interventions to reduce and/or replace television viewing may have a bigger impact on reducing overall sedentary time than targeting recreational computer use.

Although the current study is one of the largest population-level studies into the individual correlates and hierarchy of demographic characteristics associated with sedentary behaviours, these data should be interpreted with consideration of some methodological limitations. Given that the sample comprised mostly middle-age and White adults, the findings may not be generalisable to adults who are younger and/or non-White. From a measurement perspective, the data are based on self-reports and in most cases, self-reports on single-survey items. For the sedentary behaviour assessments, survey respondents provided typical hours of time in sedentary behaviour and not minutes, and thus the precision of the self-reported sedentary time is limited. These data also did not distinguish between sedentary behaviour at work versus outside of work, sedentary behaviour during weekend versus weekdays or include sitting time as a passenger versus just driving time. Future studies should consider these contextual features as well as the association between other demographic characteristics including family structure (ie, number of children in the home) and disability status with objectively measured sedentary behaviour. Consideration of a greater array of predictors of sedentary time is also likely to explain a greater proportion of the variance in this outcome as was achieved in the current study where the R2 values were <5%. It would also be informative to examine how demographic factors interact with environmental characteristics (ie, residence area) to yield different levels of sedentary time. The efficacy of demographically targeted interventions to reduce and replace sedentary behaviour with heart-healthy behaviours is also needed. Given the strong association between time spent being sedentary and the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases,6 45 this line of inquiry could ultimately inform cardiovascular disease prevention efforts.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: FP conceptualised the study, drafted and reviewed the manuscript. AL conducted the data analysis and drafted sections of the manuscript. LH conducted the data analysis and drafted sections of the manuscript. MP and JB conducted the literature searching and drafted sections of the manuscript. AH designed the data analytic approach, oversaw the data analysis and reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript draft.

Funding: FP receives support from an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) Center of Biomedical Research Excellence from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P20GM113125 and from the University of Delaware Research Foundation grant number 16A01366. FP receives free study medication from Pfizer.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The UK Biobank.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Young DR, Hivert MF, Alhassan S, et al. Sedentary Behavior and Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality: A Science Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016;134:e262–e279. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tremblay MS, Aubert S, Barnes JD, et al. Sedentary Behavior Research Network (SBRN) - Terminology Consensus Project process and outcome. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2017;14:75 10.1186/s12966-017-0525-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chomistek AK, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, et al. Relationship of sedentary behavior and physical activity to incident cardiovascular disease: results from the Women’s Health Initiative. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:2346–54. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Katzmarzyk PT, Church TS, Craig CL, et al. Sitting time and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009;41:998–1005. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181930355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Rezende LF, Rodrigues Lopes M, Rey-López JP, et al. Sedentary behavior and health outcomes: an overview of systematic reviews. PLoS One 2014;9:e105620 10.1371/journal.pone.0105620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Warren TY, Barry V, Hooker SP, et al. Sedentary behaviors increase risk of cardiovascular disease mortality in men. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010;42:879–85. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c3aa7e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Artinian NT, Fletcher GF, Mozaffarian D, et al. Interventions to promote physical activity and dietary lifestyle changes for cardiovascular risk factor reduction in adults: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010;122:406–41. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181e8edf1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lakerveld J, Loyen A, Schotman N, et al. Sitting too much: A hierarchy of socio-demographic correlates. Prev Med 2017;101:77–83. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. O’Donoghue G, Perchoux C, Mensah K, et al. A systematic review of correlates of sedentary behaviour in adults aged 18-65 years: a socio-ecological approach. BMC Public Health 2016;16:163 10.1186/s12889-016-2841-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Matthews CE, Chen KY, Freedson PS, et al. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003-2004. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:875–81. 10.1093/aje/kwm390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bowman SA. Television-viewing characteristics of adults: correlations to eating practices and overweight and health status. Prev Chronic Dis 2006;3:A38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harvey JA, Chastin SF, Skelton DA. How Sedentary are Older People? A Systematic Review of the Amount of Sedentary Behavior. J Aging Phys Act 2015;23:471–87. 10.1123/japa.2014-0164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bennie JA, Pedisic Z, van Uffelen JG, et al. The descriptive epidemiology of total physical activity, muscle-strengthening exercises and sedentary behaviour among Australian adults--results from the National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey. BMC Public Health 2016;16:73 10.1186/s12889-016-2736-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hamrik Z, Sigmundová D, Kalman M, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behaviour in Czech adults: results from the GPAQ study. Eur J Sport Sci 2014;14:193–8. 10.1080/17461391.2013.822565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dagmar S, Erik S, Karel F, et al. Gender Differences in Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior and BMI in the Liberec Region: the IPAQ Study in 2002-2009. J Hum Kinet 2011;28:123–31. 10.2478/v10078-011-0029-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Prince SA, Reed JL, McFetridge C, et al. Correlates of sedentary behaviour in adults: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2017;18:915–35. 10.1111/obr.12529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cohen SS, Matthews CE, Signorello LB, et al. Sedentary and physically active behavior patterns among low-income African-American and white adults living in the southeastern United States. PLoS One 2013;8:e59975 10.1371/journal.pone.0059975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shields M, Tremblay MS. Screen time among Canadian adults: a profile. Health Rep 2008;19:31–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bennie JA, Chau JY, van der Ploeg HP, et al. The prevalence and correlates of sitting in European adults - a comparison of 32 Eurobarometer-participating countries. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013;10:107 10.1186/1479-5868-10-107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Konevic S, Martinovic J, Djonovic N. Association of Socioeconomic Factors and Sedentary Lifestyle in Belgrade’s Suburb, Working Class Community. Iran J Public Health 2015;44:1053–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Healy GN, Clark BK, Winkler EA, et al. Measurement of adults' sedentary time in population-based studies. Am J Prev Med 2011;41:216–27. 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bernaards CM, Hildebrandt VH, Hendriksen IJ. Correlates of sedentary time in different age groups: results from a large cross sectional Dutch survey. BMC Public Health 2016;16:1121 10.1186/s12889-016-3769-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Breiman L, Friedman J, Stone CJ, et al. ; Classification and Regression Trees: Taylor & Francis, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roda C, Charreire H, Feuillet T, et al. Lifestyle correlates of overweight in adults: a hierarchical approach (the SPOTLIGHT project). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016;13:114 10.1186/s12966-016-0439-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. UK Biobank. UK Biobank: Protocol for a large-scale prospective epidemiological resource, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tyrrell J, Wood AR, Ames RM, et al. Gene-obesogenic environment interactions in the UK Biobank study. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:dyw337 10.1093/ije/dyw337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Melkevik O, Torsheim T, Iannotti RJ, et al. Is spending time in screen-based sedentary behaviors associated with less physical activity: a cross national investigation. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2010;7:46 10.1186/1479-5868-7-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Committee IR. Guidelines for data processing and analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)—Short and Long Forms, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Howley ET. Type of activity: resistance, aerobic and leisure versus occupational physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001;33 S364–S369. 10.1097/00005768-200106001-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. J. C. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, NY: Routledge Academic, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harrington DM, Barreira TV, Staiano AE, et al. The descriptive epidemiology of sitting among US adults, NHANES 2009/2010. J Sci Med Sport 2014;17:371–5. 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stamatakis E, Coombs N, Rowlands A, et al. Objectively-assessed and self-reported sedentary time in relation to multiple socioeconomic status indicators among adults in England: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006034 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Saidj M, Menai M, Charreire H, et al. Descriptive study of sedentary behaviours in 35,444 French working adults: cross-sectional findings from the ACTI-Cités study. BMC Public Health 2015;15:379 10.1186/s12889-015-1711-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Harvey JA, Chastin SF, Skelton DA. Prevalence of sedentary behavior in older adults: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013;10:6645–61. 10.3390/ijerph10126645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sugiyama T, Healy GN, Dunstan DW, et al. Is television viewing time a marker of a broader pattern of sedentary behavior? Ann Behav Med 2008;35:245–50. 10.1007/s12160-008-9017-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chastin SF, Buck C, Freiberger E, et al. Systematic literature review of determinants of sedentary behaviour in older adults: a DEDIPAC study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015;12:127 10.1186/s12966-015-0292-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hadgraft NT, Lynch BM, Clark BK, et al. Excessive sitting at work and at home: Correlates of occupational sitting and TV viewing time in working adults. BMC Public Health 2015;15:899 10.1186/s12889-015-2243-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rhodes RE, Mark RS, Temmel CP. Adult sedentary behavior: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2012;42:e3–28. 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stamatakis E, Rogers K, Ding D, et al. All-cause mortality effects of replacing sedentary time with physical activity and sleeping using an isotemporal substitution model: a prospective study of 201,129 mid-aged and older adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015;12:121 10.1186/s12966-015-0280-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hamer M, Stamatakis E, Steptoe A. Effects of substituting sedentary time with physical activity on metabolic risk. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2014;46:1946–50. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Borodulin K, Kärki A, Laatikainen T, et al. Daily Sedentary Time and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: The National FINRISK 2002 Study. J Phys Act Health 2015;12:904–8. 10.1123/jpah.2013-0364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nichols M, Townsend N, Scarborough P, et al. Cardiovascular disease in Europe 2014: epidemiological update. Eur Heart J 2014;35:2950–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Goyal A, Bhatt DL, Steg PG, et al. Attained educational level and incident atherothrombotic events in low- and middle-income compared with high-income countries. Circulation 2010;122:1167–75. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.919274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Owen N, Leslie E, Salmon J, et al. Environmental determinants of physical activity and sedentary behavior. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2000;28:153–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Achana FA, et al. Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2012;55:2895–905. 10.1007/s00125-012-2677-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.