Abstract

Introduction

Inappropriate use of antimicrobials in hospitals contributes to antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) interventions aim to improve antimicrobial prescribing, but they are often resource and personnel intensive. Computerised decision supportsystems (CDSSs) seem a promising tool to improve antimicrobial prescribing but have been insufficiently studied in clinical trials.

Methods and analysis

The COMPuterized Antibiotic Stewardship Study trial, is a publicly funded, open-label, cluster randomised, controlled superiority trial which aims to determine whether a multimodal CDSS intervention integrated in the electronic health record (EHR) reduces overall antibiotic exposure in adult patients hospitalised in wards of two secondary and one tertiary care centre in Switzerland compared with ‘standard-of-care’ AMS. Twenty-four hospital wards will be randomised 1:1 to either intervention or control, using a ‘pair-matching’ approach based on baseline antibiotic use, specialty and centre. The intervention will consist of (1) decision support for the choice of antimicrobial treatment and duration of treatment for selected indications (based on indication entry), (2) accountable justification for deviation from the local guidelines (with regard to the choice of molecules and duration), (3) alerts for self-guided re-evaluation of treatment on calendar day 4 of antimicrobial therapy and (4) monthly ward-level feedback of antimicrobial prescribing indicators. The primary outcome will be the difference in overall systemic antibiotic use measured in days of therapy per admission based on administration data recorded in the EHR over the whole intervention period (12 months), taking into account clustering. Secondary outcomes include qualitative and quantitative antimicrobial use indicators, economic outcomes and clinical, microbiological and patient safety indicators.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was obtained for all participating sites (Comission Cantonale d'Éthique de la Recherche (CCER)2017–00454). The results of the trial will be submitted for publication in a peer-reviewed journal. Further dissemination activities will be presentations/posters at national and international conferences.

Trial registration number

NCT03120975; Pre-results.

Keywords: antimicrobial stewardship, computerised decision support system, cluster randomised trial

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The use of a multicentre randomised design in a research area where there is a clear lack of high-quality trials (impact: increased internal validity).

The intervention will be tested in a diverse setting of hospitals in different cultural/language regions of the same country (impact: increased external validity) and it is relatively easy to implement uniformly (impact: increased external validity).

Overall, antimicrobial prescribing levels in the participating centres are already relatively low compared with levels in other countries (about 50–60 defined daily dose per 100 patient-days) (impact: reduced external validity; higher risk of ‘negative’ trial).

While the intervention should be implementable elsewhere, it requires modifications in the electronic health record/computerised physician order entry system which may be difficult to implement in settings using software by commercial vendors (impact: reduced external validity).

This is a cluster randomised trial with the ward as the ‘unit of randomisation’. A certain degree of ‘contamination’ is therefore unavoidable, for example, through physicians changing between wards, although the degree is lower than that for an individual randomised trial (impact: higher risk of ‘negative’ trial).

Introduction

Inappropriate use of antimicrobials in hospitals is one of the key drivers of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and Clostridium difficile infections (CDI). The purpose of antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) is, by definition, to protect this limited resource and stave off the negative consequences of its inadequate use while at the same time optimising patient outcomes.1 AMS programmes have been implemented in thousands of hospitals around the world, in some areas by legal mandate.2 3 While there is increasing evidence that AMS can generally reduce drug costs, AMR and CDI in the hospital setting, we still do not know which particular AMS interventions provide the best and most sustainable improvements in antibiotic prescribing with the best cost-effectiveness.4–6 In particular, many AMS interventions are labour-intensive and require ‘manual’ assessment of individual situations by dedicated experts such as infectious diseases specialists or pharmacists.7–11 This is problematic since it limits interventions to a small proportion of all prescriptions. Moreover, it threatens sustainability, since there are always competing hospital priorities resulting in limited resources for AMS programmes.

There is thus a need to at least partially automate AMS interventions. The 2016 AMS guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America indicate moderate-quality evidence for the incorporation of computerised decision support system (CDSS) at the time of prescribing.12 CDSSs to improve antimicrobial use have been implemented before, but there is clearly a lack of high-quality studies assessing their impact on actual antimicrobial prescribing and patient outcomes. The vast majority of studies in this area are uncontrolled before–after studies which have a much higher risk of bias and lower external validity.13 A recent systematic review of computerised decision support for antibiotic use in hospitals identified only 6 randomised controlled studies among the 81 studies included in the review, of which half (3) were single-site studies.14 Another earlier systematic review, also mostly identified low-quality, single-centre, before–after studies and concluded that ‘high quality, systematic, multisite, comparative studies are critically needed to assist organisations in making informed decisions about the most effective IT interventions.’15 Furthermore, existing studies often limited assessment to specific situations and settings, such as increasing guideline compliance in the treatment of urinary tract infection16 and critically ill patients,17 and to improve empirical antibiotic treatment for patients with suspected bacterial infections.18 CDSSs are also often overly complex, poorly designed, not integrated into the workflow, expensive or difficult to implement in heterogeneous clinical settings.19

The COMPuterized Antibiotic Stewardship Study (COMPASS) trial aims to address this evidence gap by assessing through a randomised multicentre trial, if a CDSS integrated into the workflow can reduce days of therapy (DOT) per admission in the intervention wards compared with controlled wards, over a 1-year period.

Methods and analysis

Study setting

COMPASS will be conducted in adult acute-care wards of three Swiss hospitals, one academic medical centre and two regional hospitals. HUG (Geneva University Hospitals) is one of the largest hospitals in Switzerland with about 1900 beds and 340 000 patient-days in acute care per year.20 HUG has deployed an in-house electronic health record (EHR) since 2000 and a computerised physician order entry system (CPOE) system since 2006.21 ORL (Regional Hospital of Lugano) and OSG (Regional Hospital of Bellinzona) are the largest hospitals of Southern Switzerland, with respectively 306 and 228 beds, and about 100 000 and 72 000 patients-days per year. Both hospitals have developed and adapted an EHR and CPOE system based on the in-house system of HUG since 2008 and 2014, respectively. All three hospitals have AMS programmes with regularly updated antimicrobial prescribing guidelines, review of all positive blood cultures, regular teaching sessions for physicians, and internal and external benchmarking of antibiotic use and resistance. Dedicated ward rounds in some divisions (eg, the intensive care unit and haematological or solid organ transplant wards), are also part of the AMS programme at HUG; however, these units will not be included into COMPASS. The overall framework for the COMPASS intervention is identical in all study sites; given the particularities of each setting (different EHRs, different categories of hospitals, different language, different prescribing guidelines) some details of the intervention may slightly vary between sites.

Intervention

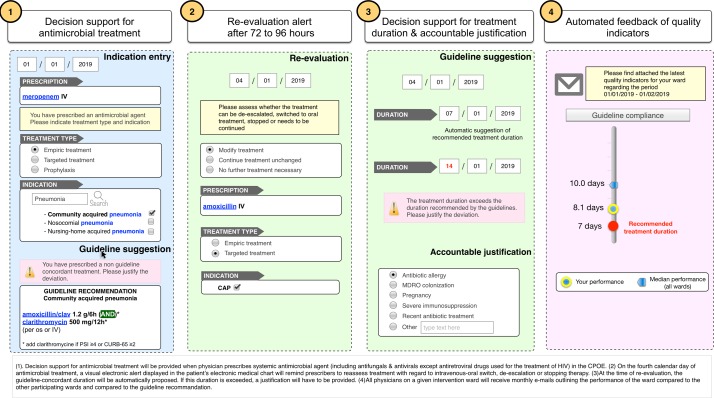

The intervention will consist of four components (figure 1):

Decision support for antimicrobial treatment with regard to the choice of antimicrobial drugs based on indication entry and current, local guidelines with accountable justification for guideline deviation.

Alerts for self-guided re-evaluation of antimicrobial therapy on calendar day 4 of therapy.

Decision support for the duration of antimicrobial treatment based on indication entry and current, local guidelines with accountable justification for guideline deviation.

Regular feedback of unit-wide antimicrobial prescribing indicators.

Figure 1.

COMPASS interventions. COMPASS, COMPuterized Antibiotic Stewardship Study; CPOE, computerised physician order entry system.

Decision support for antimicrobial treatment

When physicians prescribe a systemic antimicrobial agent (including antifungals and antivirals except antiretroviral drugs used for the treatment of HIV) in the CPOE, they will be asked to select whether the treatment is used for empiric treatment, targeted treatment or prophylaxis and to select the main indication of treatment based on a prespecified list of indications linked to an international terminology such as International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine-Clinical Terms. If a treatment recommendation exists in the local guidelines for the given indication and the treatment regimen prescribed deviates from this recommendation, the prescriber will be offered the choice to switch to the guideline-recommended treatment; otherwise prescribers will be asked to provide an ‘accountable justification’ for the deviation from the guidelines (a predefined list of potential reasons will be provided with the availability to also enter free text). The proposed system ensures that each antibiotic prescription is linked to a retrievable indication, making it possible to assess prescribing quality and to provide specific decision support.

Self-guided evaluation alert

On the fourth calendar day of antimicrobial treatment, a visual electronic alert displayed in the patient’s electronic medical chart will remind prescribers to reassess treatment with regard to intravenous-oral switch, de-escalation or stopping therapy. The alert will not be blocking (ie, if the alert is ignored by the prescriber the antimicrobial prescription will remain active), it will, however, continue to be displayed until it is addressed. The re-evaluation of treatment will be self-guided, that is, there will be no decision support guiding treatment adaptation based on patient-specific data such as vital signs, microbiological results or use of other medications. General information useful for re-evaluation, such as intravenous–oral switch criteria, will be provided as infobuttons. If the antimicrobial treatment is continued or modified, prescribers will be asked to reassess the indication (since the indication may change over a course of antimicrobial treatment). If the antimicrobial treatment is modified on calendar day 3, re-evaluation will be assumed to have taken place and no alert will be displayed on day 4.

Decision support for duration of treatment

At the time of re-evaluation, the treatment duration will have to be entered. If the entered duration exceeds the duration proposed by the guidelines, a justification will have to be provided.

Systematic audit and feedback

Quality indicators of antimicrobial prescribing such as concordance with local guidelines (in terms of duration of therapy and drug) will be automatically assessed based on the information collected during the prescribing process. All physicians on a given intervention ward will receive monthly emails outlining the performance of the ward compared with the other participating wards and compared with the guideline recommendation (if applicable). The results will be presented graphically.

Duration of the intervention period

The intervention period will last 12 months. If the intervention proves to be successful based on analyses of the data, the system will also be implemented in the control wards and the effect will continue to be monitored in all wards to assess the sustainability of the intervention after the end of the research study.

Control

The control will consist of routine, ‘standard-of-care’ AMS as described above.

Sample size

The sample size calculation is based on the primary outcome (DOT per admission) and has been performed taking into account the pair-matched and clustered design of the study according to the approach proposed by Hayes and Bennett.22 Assuming 12 wards per arm, with an average size of 500 admissions, antibiotic use of 4.0 DOT/admission in the control group with an SD of 1.0 (based on preliminary antibiotic use data) and a two-sided type I error of 0.05 we would have a power of 80% to detect a relative difference in average DOT/admission between the intervention and control arm of at least 7.7%. Antibiotic stewardship interventions described in the published literature have often exceeded this effect size.

Inclusion criteria and randomisation

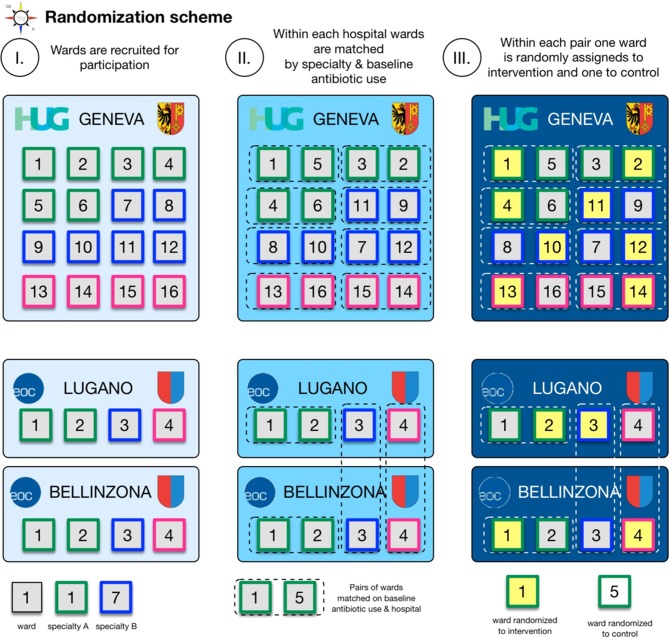

Twenty-four acute wards fulfilling the inclusion criteria (table 1) will be recruited by approaching the heads of the concerned departments (16 wards at HUG, 4 wards at ORL and OSG each). Acute wards will be paired according to centre, specialty (eg, medicine, surgery, geriatrics) and baseline antibiotic use in DOT/admission. Wards will be randomised 1:1 to the intervention or control arm within each pair using an online random sequence generator (figure 2). The randomisation plan will be established by personnel not directly involved in the study. Depending on the recruitment of wards, specialities may be matched across ORL and OSG since due to the smaller size these hospitals may only have one ward per specialty (eg, visceral surgery, orthopaedics). In that case randomisation may be constrained to make sure that each hospital has at least one intervention ward in either specialty (eg, orthopaedics or visceral surgery).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

| Cluster level (wards) |

|

|

| Physician level |

|

|

| Patient level |

|

|

CPOE, computerised physician order entry; ICU, intensive care unit.

Figure 2.

Randomisation scheme. Twenty-four acute wards fulfilling the inclusion criteria will be recruited (16 wards at HUG, 4 wards at ORL and OSG each). Acute wards will be paired according to centre, specialty (eg, medicine, surgery, geriatrics) and baseline antibiotic use in days of therapy/admission. Wards will be randomised 1:1 to the intervention or control arm within each pair using an online random sequence generator. EOC, Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale; HUG, Geneva University Hospitals; ORL, Regional Hospital of Lugano; OSG, Regional Hospital of Bellinzona.

Outcomes

Table 2 gives a detailed overview of the primary and secondary outcomes, the underlying hypothesis and the justification for the choice of outcomes.

Table 2.

Main study outcomes and corresponding hypotheses evaluated within the COMPASS trial

| Outcome component | Relevant hypothesis (If not otherwise stated, the hypothesis refers to the expected effect of the intervention.) |

Rationale for outcome selection | |

| Primary outcome | Days of therapy (DOT) of antibiotics* per admission. | Reduction in antibiotic use through shortening of duration of treatment and reduction in combination therapies. | DOT is an easily measurable, objectively assessable, outcome that is supported by expert consensus.23 Admission was chosen as the denominator for the primary outcome rather than PDs since reductions in antimicrobial treatment duration (reflected by a reduction in DOT) may induce a reduction of length of stay (LOS). This may have as consequence that DOT per PDs changes little despite a reduction in antibiotic exposure since both the numerator and denominator are reduced. |

| Secondary outcomes: quantitative antimicrobial use† | DOT per 100 patient-days (PD). Defined daily doses (DDD) per 100 PD and per admission. Antimicrobial days (ADs)‡ per 100 PD and per admission. Days per treatment period overall and for specific indications.§ |

Reduction in antimicrobial use through shortening of duration of treatment and reduction in combination therapies. | DDDs are the most widely used metric for antimicrobial consumption and are therefore most suitable for comparisons with other settings. ADs are a further metric that has been proposed to assess antibiotic use. Both PDs and admissions have been proposed as denominators.23 28–31

A treatment period is defined as antibiotic treatment not interrupted by more than one calendar day or discharge. |

| Secondary outcomes: clinical outcomes | Thirty-day mortality In hospital mortality. |

The intervention is safe and does not result in an increase in mortality or readmissions. | Clinical outcomes are included to demonstrate the safety of the intervention, the improvement of quality of care and the absence of unintended consequences. The clinical outcomes are chosen based on their objectivity, the ease of obtaining the data and expert consensus.28 32 |

| Unplanned hospital readmissions within Thirty days after discharge. Hospital LOS. Intensive or intermediate care unit admission from COMPASS wards. |

Similar LOS or a reduction in the LOS. No increase in the no of intensive care unit or intermediate care unit admissions. |

||

| Secondary outcomes: qualitative antimicrobial use | Concordance of empirical antibiotic therapy with local guidelines (taking into account justified exceptions) with regard to the choice of molecules and duration of treatment. Switch to oral therapy when appropriate De-escalation of antimicrobial therapy by calendar day 4 of treatment Appropriate diagnostic exams. |

Improved quality of antimicrobial use. | Improving the quality of antimicrobial use is one of the key goals of antimicrobial stewardship (AMS). Valid, reliable and universally accepted metrics for measuring appropriateness of antimicrobial use are difficult to define and labour-intensive to assess.30 Qualitative antimicrobial use outcomes will be assessed through manual review of a random selection of charts (at least 50 charts per ward over the 12-month period) by infectious diseases specialists using prespecified criteria for appropriateness. A subselection of charts (about 10% of the sample) will be reviewed independently by two reviewers (blinded to ward assignment) to determine interobserver variability. |

| Secondary outcomes: microbiological outcomes and healthcare-associated infections | Incidence of healthcare facility-onset Clostridium difficile denominated per 10 000 PD and admission (attributed to unit). Incident clinical cultures with multidrug resistant organisms (MRSA, ESBL-E, CPE, VRE, multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa) denominated per 1000 PD and admission. |

Reduced incidence of healthcare facility-onset C. difficile infection (CDI). Reduced incidence of multidrug-resistant organisms. |

Limiting CDI and the emergence and transmission of AMR is one of the key goals of AMS. There is expert consensus that the incidence of CDI and drug-resistant pathogens are key metrics to assess the impact of AMS.23

Since these outcomes are influenced by numerous other factors and would require a very large sample size, they are secondary outcomes and not primary outcomes in this study. |

| Secondary outcomes physician satisfaction | User satisfaction with the system. | Users will be satisfied with the system. | A major obstacle to the use of CDSS is the lack of buy-in from prescribers and unintended consequences such as ‘alert fatigue’. |

| Secondary outcomes: economic | Costs of administered antimicrobials (overall and by class) per admission and per admission receiving antibiotics. Costs of the intervention Total costs of hospitalisation. |

Decreased overall direct costs for antimicrobials. | Reducing the cost of antimicrobial therapy is a goal secondary to that of improving quality of care and patient safety but is one of great interest to administrators.33 All costs will be assessed from the perspective of the hospital. |

| Other outcomes | Number of infectious diseases consultations. | No difference in the number of infectious diseases consultations between the groups. | An unintended consequence of the intervention may be an increase in the requests for infectious diseases consultations which may impact antibiotic use and patient outcomes.34 |

*The primary outcome will be DOT for antibiotics belonging to Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System class J01 (anti-infectives for systemic use) plus oral metronidazole (P01AB01), oral vancomycin (A07AA09), rifampicin (J04AB02) and fidaxomicin (A07AA12).

†In addition to overall antibiotic use as defined above, outcomes for DOT and DDD will also be assessed for different antibiotic classes, for antifungals, for non-HIV antivirals and for selected specific antibiotics.

‡The metric AD is equivalent to ‘length of therapy’.35

§To make a comparison possible between intervention and control wards, the ‘diagnosis’ will be based on administrative discharge data. The most common infections (community-acquired pneumonia, upper urinary tract infection, etc) will be analysed.

CDSS, Computerised Decision Support System; COMPASS, COMPuterized Antibiotic Stewardship Study; CPE, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae; ESBL-E, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; VRE, vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

Primary outcome

The difference in overall systemic antibiotic use measured in DOT of systemic antibiotic use per admission based on electronically recorded drug administration data (for details see table 2).23 One DOT represents a specific antibiotic administered to an individual patient on a calendar day independent of dose and route.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes include quantitative and qualitative antimicrobial use indicators, clinical outcomes, microbiological outcomes, economic outcomes and user satisfaction (see table 2 for more detailed definitions).24 25

Blinding

Neither the study staff implementing the intervention, nor the physicians targeted by the intervention, nor the patients receiving treatments will be blinded to an individual ward’s assignment group since the nature of the intervention makes this impossible. Extraction of the primary outcome measures will be performed primarily by administrative staff not involved in the study. The data analysts will be blinded to the treatment allocation.

Study schedule

The intervention is scheduled to begin mid-2018.

Analysis

Outcome variables will first be summarised across treatment and intervention groups and then explored using descriptive statistics, taking into account the matched design by sandwich variance estimators for CIs. The DOT/admission at the individual level will be compared between the intervention groups using a random-effects Poisson model with two levels, taking into account clustering within hospitals and the matched pairs. The following confounders will be considered: sex, age, type of comorbidities and type of admission (internal medicine vs other), whereby all variables that result in a change of >5% in the coefficient for the intervention effect in bivariate regression will be added to the multivariate model, and the most parsimonious model will be selected through the conditional AIC. Collinearity will be checked through a correlation matrix, whereby the most relevant, clinical variable will be selected in case of R2 >0.8.

Data collection and management

Most data will be retrieved from the hospital’s data warehouses. De-identified data will be stored in password-protected Microscoft Excel files on secured hospital servers. For the secondary outcome ‘qualitative assessment of antibiotic use’, an elecronic Case Report Form (eCRF) will be created in an electronic data capture system such as Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap Consortium).

For analysis data will be imported into a statistical programme, such as Stata V.15 (StataCorp) or ‘R’ (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Only investigators directly involved in the trial will have access to the data. The data will be stored on secure servers with backup systems for 10 years.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the development of the research question, study design or any other part of this protocol.

Ethics and dissemination

A waiver of informed consent by prescribers and patients was granted under the condition to provide an information leaflet to patients in the participating wards. Several publications in peer-reviewed journals are planned from this trial: these will include the description of the development of the intervention and main findings of the trial. Furthermore, the findings will be presented at national and international conferences.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the COMPASS trial will be one of the first multicentre, cluster randomised controlled trials to assess whether a pragmatic CDSS integrated into the EHR can reduce overall antibiotic use in a diverse setting of hospitals. Our study has several strengths and limitations which are outlined in the article summary. COMPASS addresses many of the limitations of previous studies regarding the impact of CDSS on antimicrobial use in hospitals.13 A limitation of COMPASS is the fact that the combination of different interventions will make it difficult to identify which component is the most effective; this can hopefully be addressed in further research. We believe that COMPASS is innovative in combining relatively new strategies for AMS, such as ‘accountable justification’ with well-established strategies like audit and feedback leveraging the potentials of the EHR.26 27 If effective, similar systems could be adapted in many hospitals given the relatively ‘simple’ design of the CDSS intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all members of the COMPASS study team for the valuable contribution in setting up the study. The COMPASS study team consists of members from Geneva University Hospitals and from the Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale, Carlo Balmelli, Nicolò Centemero, Valentina Coray, Serge Da Silva, Emmanuel Durand, Christophe Marti, Lorenzo Moja, Francesco Pagnamenta, Marie-Françoise Piuz, Javier Portela, Virginie Prendki, Jerôme Stirnemann, Nathalie Vernaz.

Footnotes

Contributors: BDH conceived the original idea for this study which was further developed with all authors. BDH, EB, SH, LK and RM secured funding for the study. BDH and GC wrote the first draft of this manuscript. MDK provided input regarding the sample size calculations and statistical analysis. The manuscript was reviewed and edited by all authors: GC, MDK, BWS, RV, SH, LK, LE, RM, EB and BDH.

Funding: This work is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 407240_167079) in the context of the Swiss National Research Programme 72 "Antimicrobial Resistance" (www.nfp72.ch).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The trial has been approved by the competent ethics committees in Geneva and Ticino (CCER no 2017–00454).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

References

- 1. Dyar OJ, Huttner B, Schouten J, et al. What is antimicrobial stewardship? Clin Microbiol Infect 2017;23:793–8. 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Trivedi KK, Dumartin C, Gilchrist M, et al. Identifying best practices across three countries: hospital antimicrobial stewardship in the United Kingdom, France, and the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59(Suppl 3):S170–8. 10.1093/cid/ciu538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Howard P, Pulcini C, Levy Hara G, et al. An international cross-sectional survey of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015;70:1245–55. 10.1093/jac/dku497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Davey P, Marwick CA, Scott CL, et al. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;2:CD003543 10.1002/14651858.CD003543.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baur D, Gladstone BP, Burkert F, et al. Effect of antibiotic stewardship on the incidence of infection and colonisation with antibiotic-resistant bacteria and Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17:990–1001. 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30325-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Naylor NR, Zhu N, Hulscher M, et al. Is antimicrobial stewardship cost-effective? A narrative review of the evidence. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017;23:806–11. 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lesprit P, de Pontfarcy A, Esposito-Farese M, et al. Postprescription review improves in-hospital antibiotic use: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015;21:180.e1–7. 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Senn L, Burnand B, Francioli P, et al. Improving appropriateness of antibiotic therapy: randomized trial of an intervention to foster reassessment of prescription after 3 days. J Antimicrob Chemother 2004;53:1062–7. 10.1093/jac/dkh236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Manuel O, Burnand B, Bady P, et al. Impact of standardised review of intravenous antibiotic therapy 72 hours after prescription in two internal medicine wards. J Hosp Infect 2010;74:326–31. 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cosgrove SE, Seo SK, Bolon MK, et al. Evaluation of postprescription review and feedback as a method of promoting rational antimicrobial use: a multicenter intervention. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2012;33:374–80. 10.1086/664771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Uçkay I, Vernaz-Hegi N, Harbarth S, et al. Activity and impact on antibiotic use and costs of a dedicated infectious diseases consultant on a septic orthopaedic unit. J Infect 2009;58:205–12. 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an Antibiotic Stewardship Program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis 2016;62:1197–202. 10.1093/cid/ciw217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Kraker MEA, Abbas M, Huttner B, et al. Good epidemiological practice: a narrative review of appropriate scientific methods to evaluate the impact of antimicrobial stewardship interventions. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017;23:819–25. 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Curtis CE, Al Bahar F, Marriott JF. The effectiveness of computerised decision support on antibiotic use in hospitals: A systematic review. PLoS One 2017;12:e0183062 10.1371/journal.pone.0183062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baysari MT, Lehnbom EC, Li L, et al. The effectiveness of information technology to improve antimicrobial prescribing in hospitals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Med Inform 2016;92:15–34. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Demonchy E, Dufour JC, Gaudart J, et al. Impact of a computerized decision support system on compliance with guidelines on antibiotics prescribed for urinary tract infections in emergency departments: a multicentre prospective before-and-after controlled interventional study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014;69:2857–63. 10.1093/jac/dku191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nachtigall I, Tafelski S, Deja M, et al. Long-term effect of computer-assisted decision support for antibiotic treatment in critically ill patients: a prospective ’before/after' cohort study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005370 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Paul M, Andreassen S, Tacconelli E, et al. Improving empirical antibiotic treatment using TREAT, a computerized decision support system: cluster randomized trial. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006;58:1238–45. 10.1093/jac/dkl372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rawson TM, Moore LSP, Hernandez B, et al. A systematic review of clinical decision support systems for antimicrobial management: are we failing to investigate these interventions appropriately? Clin Microbiol Infect 2017;23:524–32. 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. HUG en bref. chiffres clés. 2014. https://www.hug-ge.ch/sites/interhug/files/structures/chiffres_cles_2017/documents/hug_enbref_2017.pdf

- 21. Iten A, Perrier A, Lovis C. [Deployment of a computerized physician order entry: description of the process and challenges]. Rev Med Suisse 2006;2:2344–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hayes RJ, Bennett S. Simple sample size calculation for cluster-randomized trials. Int J Epidemiol 1999;28:319–26. 10.1093/ije/28.2.319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moehring RW, Anderson DJ, Cochran RL, et al. Expert Consensus on Metrics to Assess the Impact of Patient-Level Antimicrobial Stewardship Interventions in Acute-Care Settings. Clin Infect Dis 2017;64:377–83. 10.1093/cid/ciw787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Versporten A, Gyssens IC, Pulcini C, et al. Metrics to assess the quantity of antibiotic use in the outpatient setting: a systematic review followed by an international multidisciplinary consensus procedure. J°Antimicrob Chemother 2018;73:vi59–vi66. 10.1093/jac/dky119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Le Maréchal M, Tebano G, Monnier AA, et al. Quality indicators assessing antibiotic use in the outpatient setting: a systematic review followed by an international multidisciplinary consensus procedure. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018;73:vi40-vi49 10.1093/jac/dky117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meeker D, Linder JA, Fox CR, et al. Effect of Behavioral Interventions on Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing Among Primary Care Practices: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016;315:562–70. 10.1001/jama.2016.0275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012:CD000259 10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dik JW, Hendrix R, Poelman R, et al. Measuring the impact of antimicrobial stewardship programs. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2016;14:569–75. 10.1080/14787210.2016.1178064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morris AM, Brener S, Dresser L, et al. Use of a structured panel process to define quality metrics for antimicrobial stewardship programs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2012;33:500–6. 10.1086/665324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Morris AM. Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs: Appropriate Measures and Metrics to Study their Impact. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis 2014;6:101–12. 10.1007/s40506-014-0015-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Proposals for EU guidelines on the prudent use of antimicrobials in humans. 2017. https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/proposals-eu-guidelines-prudent-use-antimicrobials-humans (accessed 27 Feb 2018).

- 32. Akpan MR, Ahmad R, Shebl NA, et al. A Review of Quality Measures for Assessing the Impact of Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs in Hospitals. Antibiotics 2016;5:5 10.3390/antibiotics5010005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ibrahim NH, Maruan K, Mohd Khairy HA, et al. Economic Evaluations on Antimicrobial Stewardship Programme: A Systematic Review. J Pharm Pharm Sci 2017;20:397–406. 10.18433/J3NW7G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schmitt S, McQuillen DP, Nahass R, et al. Infectious diseases specialty intervention is associated with decreased mortality and lower healthcare costs. Clin Infect Dis 2014;58:22–8. 10.1093/cid/cit610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Polk RE, Hohmann SF, Medvedev S, et al. Benchmarking risk-adjusted adult antibacterial drug use in 70 US academic medical center hospitals. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53:1100–10. 10.1093/cid/cir672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.