Abstract

Study objective

To evaluate the implementation of the Ohio Emergency and Acute Care Facility Opioids and Other Controlled Substances Prescribing Guidelines and their perceived impact on local policies and practice.

Methods

The study design was a cross-sectional survey of emergency department (ED) medical directors, or appropriate person identified by the hospital, perception of the impact of the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines on their departments practice. All hospitals with an ED in Ohio were contacted throughout October and November 2016. Distribution followed Dillman’s Tailored Design Method, augmented with telephone recruitment. Hospital chief executive officers were contacted when necessary to encourage ED participation. Descriptive statistics were used to assess the impact of opioid prescribing policies on prescribing practices.

Results

A 92% response rate was obtained (150/163 EDs). In total, 112 (75%) of the respondents stated that their ED has an opioid prescribing policy, is adopting one or is implementing prescribing guidelines without a specific policy. Of these 112 EDs, 81 (72%) based their policy on the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines. The majority of respondents strongly agreed/agreed that the prescribing guidelines have increased the use of the prescription drug monitoring programme (86%) and have reduced inappropriate opioid prescribing (71%).

Conclusion

This study showed that the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines have been widely disseminated and that the majority of EDs in Ohio are using them to develop local policies. The majority of respondents believed that the Ohio opioid prescribing guidelines reduced inappropriate opioid prescribing. However, prescribing practices still varied greatly between EDs.

Keywords: health policy, quality in health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

All emergency departments (EDs) in hospitals in Ohio were included in the study.

A large response rate of 92% (150/163) was obtained for the survey.

Survey reported ED medical directors’ perceptions of prescribing practices in their EDs.

Survey results are self-reported and may be influenced by recall or social desirability bias.

Introduction

Background

Drug overdoses are the leading cause of unintentional death in the USA, driven largely by opioids (66%), both prescription and illicit.1 2 In total, 40% of opioid-related deaths are due to a prescription opioid, with the remainder primarily driven by heroin and illicitly manufactured fentanyl (IMF).3 Although heroin and IMF-related deaths are the primary cause of opioid-related deaths in the USA, there are significant geographical variations in opioid prescribing practices and involvement of specific opioid compounds in overdose deaths.2 4 Reducing unnecessary exposure to prescription opioids may prevent the development of opioid use disorder that is later supplemented or replaced by illicit opioids.5 This has led to the implementation of multiple strategies aimed at improving opioid prescribing around the USA.2 6 Such strategies appear to be improving the situations in some states, as the rates of overdose deaths involving a prescription (age adjusted) have steadied from 2011 to 20155 and the annual opioid prescribing rate has decreased from 2012 to 2015.4

This paper will focus on strategies used in the emergency room setting in Ohio, as Ohio had the third highest rate of prescription opioid-related overdose deaths and highest number of prescription opioid-related overdose deaths in the USA in 2016.7 Ohio has persistently had high overdose deaths over the last decade and has been comprehensive in its approach to reduce them.5 8 Many state-based initiatives were developed by the Governor’s Cabinet Opiate Action Team (GCOAT) and have also included the development of numerous opioid prescribing guidelines. This includes the Ohio Emergency and Acute Care Facility Opioids and Other Controlled Substances Prescribing Guidelines, referred to as the Ohio emergency department (ED) Opioid Prescribing Guidelines, in 2012.9 Similar guidelines have been released by the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) in 2012.10 The Ohio guidelines were endorsed and publicised by nine organisations, including the Ohio chapter of the ACEP, the Ohio State Medical Association and the Ohio Hospital Association.9

Physicians working in ED may require assistance as it has been estimated that up to 42% of EDs may be misused by patients.11 Development and dissemination of high-quality clinical practice guidelines can assist physicians in making informed prescribing decisions while mitigating the risks associated with medications, such as opioids. A qualitative study of 61 emergency physicians presented at the 2012 national ACEP research and education conference found that, in general, physicians viewed opioid prescribing guidelines in EDs favourably.12 They believed the guidelines assisted in standardising practice patterns at the institutional level, reduced the frequency and dosage of opioid prescriptions, improved patient safety and protected them from liability and patient complaints. However, it was also noted that many physicians were unaware of specific recommendations listed in the guidelines.12 Recent evidence further supports this as opioid prescribing has declined in Ohio by ED physicians since the release of the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines.13 However, it is unknown which recommendations in the guidelines have led to this change and which ones may need to be refined. The Ohio Department of Health (ODH) contracted with our research team to evaluate the extent to which the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines have been implemented in hospitals with an ED in Ohio.9 As a result, this study aimed to evaluate the implementation of the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines and their perceived impact on hospital policies and practices.

Methods

Study design, setting and survey development

The study design was a cross-sectional survey of ED medical directors, or appropriate person identified by the hospital, in all Ohio hospitals with an ED throughout October and November 2016. A 10-question survey based on the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines was developed by experts on the research team who have experience in survey design and opioid prescribing in EDs. A literature review and input from ODH also ensured content validity of the survey. The survey instrument included primarily closed-ended questions using a Likert-scale to evaluate the implementation of the guidelines and local opioid policies. Questions were chosen to correspond with each recommendation in the guideline. Additional questions focused on the respondents’ demographic details, strategies used to implement the guidelines and the perceived benefits of the guidelines. Once developed, the survey was pretested for key elements of accessibility, usability and understandability by five ED medical directors and physicians. The final survey was then made available as a paper version and a web-based version using (Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)).14

Selection of participants

The survey was designed to be completed by one person at each hospital ED in Ohio. The survey targeted ED medical directors or those identified by ED personnel as the most appropriate person to complete the survey. Hospitals with an ED in Ohio were identified through the ODH Office of Health Assurance and Licensing. As of September 2016, 271 hospitals were registered in Ohio; 164 of these hospitals had an ED; however, 1 hospital had closed just prior to the study commencement. Hospitals’ mailing addresses, phone numbers and an email address for their respective chief executive officer (CEO) were obtained from hospital registration reports.

Survey distribution followed Dillman’s Tailored Design Method, a mixed-mode method including postal mail and email, augmented by telephone interviews to maximise the response rate.15 Dillman’s Tailored Design Method is based on social exchange theory, which focuses on establishing trust, increasing benefits and decreasing costs, to improve response rates.15 One strategy recommend by Dillman is to provide participants with a token of appreciation in advance. This token can be as small as US$2 as it increases the benefit and establishes trust.15 A US$10 incentive was chosen as it was the smallest amount that could be preloaded on a prepaid credit card.

All hospitals in Ohio with an ED were initially telephoned (day 0) to inform potential participants about the survey and to offer to complete the survey over the phone. If potential participants were unavailable or unable to complete the survey over the phone, a letter was mailed with a web-link to the survey and a US$10 incentive (day 1). A letter containing a US$10 incentive was also mailed to the hospital’s CEO asking the CEO to pass the survey web-link to the potential participant (day 1). Three days later (day 4), the letters were followed up with an email to both the potential participant and the hospital’s CEO. If no response was received, a reminder email was sent on day 10, a hard copy of the survey was mailed on day 18 and a final reminder email was sent on day 22. To further increase the response rate, a reminder was sent to rural hospitals through the ODH State Office of Rural Health and to ED physicians through the Ohio Chapter of the ACEP. These emails were sent on day 4 with a reminder sent a week later. The most senior ED physicians’ responses were used for hospitals where the ED medical director could not be contacted or identified.

Patient and public involvement

This study was designed and conducted by the research team with assistance from the Ohio ODH. Patients and the public were not involved in this study.

Analysis

All survey data were managed using REDCap.14 Hospitals were classified as being urban or rural based on the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy definition. Descriptive statistics, reported as percentages, were used to summarise the demographics and survey responses. All analyses were performed using Stata SE V.13.1 (StataCorp).

Results

Characteristics of study subjects

ED personnel at 163 hospitals were contacted to participate in this study and 150 responses were received; yielding 92% response rate. Among those that responded, 57% (86/150) were from urban hospitals and 43% (64/150) were from rural hospitals. Table 1 shows the characteristics of respondents and their hospitals. The ED medical director completed the survey for 79% (119/150) of the EDs. For the remaining EDs, either an emergency physician (13%, 19/150), an ED nursing director (6%, 9/150) or a pharmacist (2%, 3/150) completed the survey.

Table 1.

Characteristics of respondents and their hospitals (n=150)

| Respondents’ position | n (%) |

| Medical director | 119 (79.3) |

| Emergency physician | 19 (12.7) |

| Nursing director | 9 (6.0) |

| Pharmacist | 3 (2.0) |

| Rural | |

| Urban | 86 (57.3) |

| Rural | 64 (42.7) |

| Region of Ohio | |

| Central | 21 (14.0) |

| Northeast | 48 (32.0) |

| Northwest | 34 (22.7) |

| Southeast | 15 (10.0) |

| Southwest | 32 (21.3) |

| Hospital funding type | |

| Non-government not for profit | 130 (86.7) |

| Government non-federal | 16 (10.7) |

| Investor owned for profit | 4 (2.7) |

| Hospital classification | |

| Short-term acute hospital | 115 (76.7) |

| Critical access hospital | 32 (21.3) |

| Children’s hospital | 3 (2.0) |

Main results

Implementation of Ohio opioid prescribing policy

Overall, 75% (112/150) of respondents stated that their ED either had an opioid prescribing policy, was in the process of adopting one or was implementing guidelines without a specific policy. Of these 112 EDs, 72% (81/112) based their policy and practices on the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines. Other prescribing guidelines on which respondents based their policies and practices were the ACEP guidelines (34%, 38/112), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines (29%, 32/112) and the American Academy of Emergency Medicine (AAEM) guidelines (13%, 15/112).

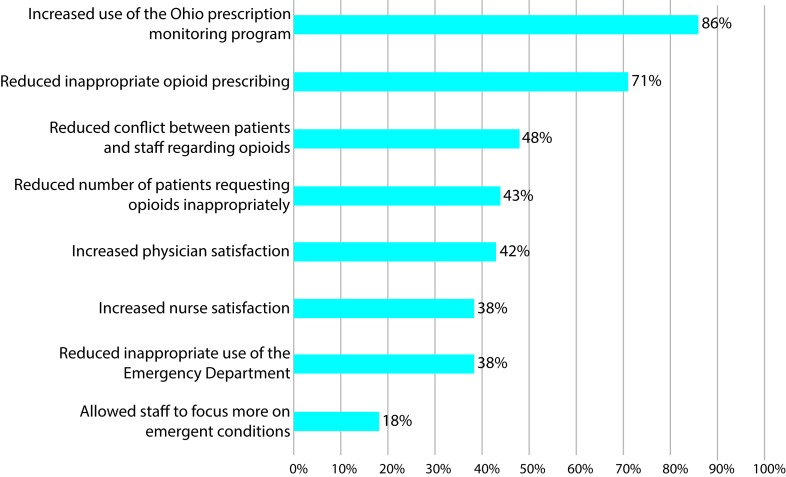

Among the EDs that reported developing or having an opioid prescribing policy, the majority strongly agreed/agreed that the guidelines have increased the use of Ohio’s prescription drug monitoring programme (86%) and the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines have reduced inappropriate opioid prescribing (71%). The other potential benefits of the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines are displayed in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Perceived impact of the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines from respondents who follow an opioid prescribing policy (n = 106).

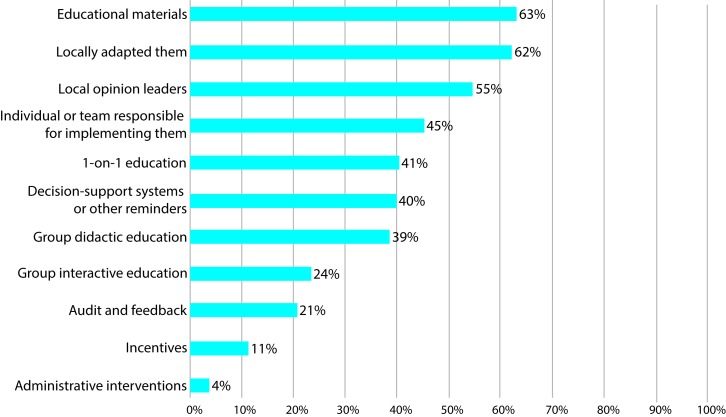

The most common strategies used to implement opioid prescribing policies and guidelines were developing educational materials, adapting the educational materials locally to their patient population and using local opinion leaders to encourage opioid prescribing policy and guideline implementation (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Strategies used to implement opioid prescribing policies and guidelines (n = 106).

Opioid prescribing practices

Table 2 shows respondents’ perceptions of opioid prescribing practices for pain in the last month in their EDs. For the management of acute pain, respondents rarely (<5% of patients) used intravenous meperidine, provided a prescription for long-acting or controlled-release opioids, or replaced opioids that were lost, destroyed or stolen as recommended in the guidelines. However, one-third of respondents (33%) reported writing an opioid prescription for more than 3 days for 5% or more of their patients with acute pain. For the management of chronic pain, respondents rarely (<5% of patients) used intravenous meperidine, provided a prescription for long-acting or controlled-release opioids, replaced opioids that were lost, destroyed or stolen, or provided replacement doses of opioid replacement therapy as recommended in the guidelines. However, 64% of respondents reported using intramuscular or intravenous opioids in 5% or more of their patients with chronic pain. Also, approximately one-third of respondents provided a prescription for opioids in 5% or more of their patients with chronic pain who: (1) had received an opioid prescription from another provider and (2) had previously presented with the same problem in the last month.

Table 2.

Respondents’ perception of frequency of opioid treatment in the last month in their emergency department (n=134)*

| Provided to patients with acute pain | Never | 1%–4% | 5%–24% | 25%–49% | ≥50% |

| n (%) | |||||

| Intravenous meperidine | 114 (85) | 13 (10) | 5 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Opioid prescription that: | |||||

| Is long acting or controlled release | 110 (82) | 18 (13) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Replaces those lost, destroyed or stolen | 91 (68) | 31 (23) | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Is for more than a 3-day supply | 30 (22) | 49 (37) | 30 (22) | 15 (11) | 3 (2) |

| Provided to patients with chronic pain | |||||

| Intramuscular or intravenous opioids | 6 (4) | 34 (25) | 52 (39) | 24 (18) | 9 (7) |

| Intravenous meperidine | 118 (88) | 11 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Replacement doses of opioid substitution therapy | 121 (90) | 5 (4) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Opioid prescription that: | |||||

| Is long acting or controlled release | 113 (84) | 16 (12) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Replaces those lost, destroyed or stolen | 97 (72) | 26 (19) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Is for more than a 3-day supply | 52 (39) | 43 (32) | 23 (17) | 10 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Opioid prescription for: | |||||

| Patients who received an opioid prescription within past month | 27 (20) | 49 (37) | 36 (27) | 9 (7) | 2 (1) |

| Patients who presented with the same problem within past month | 20 (15) | 64 (48) | 30 (22) | 9 (7) | 0 (0) |

*Although there were 134 respondents, some responded as ‘do not know’ or did not complete this specific question and are not represented in the table.

Opioid prescribing procedure

Table 3 shows respondents’ perceptions of tasks performed, recommended in the guidelines, for any opioid prescription written in the last month in their EDs. Large variations were reported from EDs around Ohio. For example, 23% of EDs provided written information on the addictive nature of opioids to more than 95% of their patients who received an opioid prescription, while another 23% of EDs never did. Some recommendations in the guidelines were also largely not implemented. Over 80% of EDs never get patients who are prescribed an opioid to sign a pain agreement, and 44% reported that they never receive a consultation from the hospital’s palliative or pain service.

Table 3.

Respondents’ perception of tasks performed when giving an opioid prescription in the last month in their ED (n=134)*

| Task performed | Never | 1%–4% | 5%–24% | 25%–49% | 50%–74% | 75%–95% | >95% |

| n (%) | |||||||

| Confirmed identity by photo identification | 23 (17) | 4 (3) | 9 (7) | 2 (1) | 5 (4) | 23 (17) | 31 (23) |

| Searched the Ohio prescription monitoring programme | 1 (1) | 8 (6) | 17 (13) | 25 (19) | 27 (20) | 33 (25) | 16 (12) |

| Completed urine or other drug screen | 16 (12) | 50 (37) | 37 (28) | 7 (5) | 3 (2) | 4 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Obtained records from other providers | 16 (12) | 39 (29) | 24 (18) | 17 (13) | 8 (6) | 8 (6) | 7 (5) |

| For patients with chronic pain, contacted their routine opioid prescriber | 7 (5) | 54 (40) | 34 (25) | 16 (12) | 9 (7) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| For patients who visit the ED frequently, conducted a case review or management | 30 (22) | 30 (22) | 21 (16) | 13 (10) | 5 (4) | 18 (13) | 2 (1) |

| Obtained a consultation from the hospital’s palliative or pain service | 59 (44) | 50 (37) | 10 (7) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Had patients sign a pain agreement | 108 (81) | 14 (10) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Provide patients with written information on: | |||||||

| Addictive nature of opioids | 31 (23) | 16 (12) | 5 (4) | 10 (7) | 4 (3) | 13 (10) | 31 (23) |

| Potential dangers of the opioid misuse | 31 (23) | 21 (16) | 5 (4) | 10 (7) | 3 (2) | 13 (10) | 31 (23) |

| Appropriate storage and disposal of opioids | 43 (32) | 14 (10) | 8 (6) | 8 (6) | 3 (2) | 4 (3) | 24 (18) |

| The facility’s policy regarding the prescribing of opioids | 44 (33) | 14 (10) | 18 (13) | 13 (10) | 5 (4) | 6 (4) | 7 (5) |

*Some rows do not add up to 100% (n=134) as ‘do not know’ or incomplete responses are not included in the table.

ED, emergency department.

Discussion

This study found that the majority of Ohio EDs are aware of the need to improve appropriate opioid prescribing and either have a hospital-based opioid prescribing policy, are in the process of adopting one or are implementing guidelines without a specific policy. Most EDs are aware of the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines and are using them to be more judicious in opioid prescribing decisions. The results of this study demonstrate that ED medical directors, and their delegates, in Ohio believe that the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines have at least been partially implemented and have formed the basis for hospital-level prescribing policies. Factors suggesting that the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines were influential include the number of respondents who reported familiarity, perceived impact in terms of improved opioid prescribing and an increase in the use of the Ohio prescription drug monitoring programme. These findings are consistent with recent evidence that indicated a decline in opioid prescribing by Ohio ED physicians since the release of the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines.13 This successful implementation of the guidelines may, in part, be due to the multistakeholder input that led to the development of the guidelines and broad support from professional societies and government officials. The fact that they are being implemented so widely indicates that the guidelines offer reasonable advice to ED physicians.

Although respondents generally reported their ED practices aligned with the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines, variability in ED prescribing practices was also observed. The largest variability in ED prescribing practices was the percentage of patient with chronic pain treated with intramuscular or intravenous opioids. Also, large variability was observed in the percentage of patients being given a prescription for an opioid for more than 3 days, regardless if it was for chronic or acute pain. Such prescribing variability may highlight that these specific guideline recommendations may not be practical or that respondents generally do not agree with them. A revision of these statements and guidance on which clinical scenario they apply to may ensure the guidelines support best practices.

Furthermore, similar variability in ED practices was observed, including the use of Ohio’s prescription drug monitoring programme and education provided to patients. The largest variation in ED practices was observed for opioid prescriptions being provided to patients with chronic pain even though they had previously presented with the same problem or had received an opioid prescription from another provider in the last month. This lack of standardisation in the care and information patients receive is concerning and requires additional investigation to identify their cause.

It is also acknowledged that ED physicians make a relatively small contribution to the overall number of opioids prescribed. In Ohio, ED physicians write approximately 5% of all opioid prescriptions.16

Hence, guidelines aimed at primary care practitioners that commonly prescribe opioids should also be implemented, such as those developed by the GCOAT17 18 or the CDC.19 However, Barnett et al 20 showed that long-term opioid use is associated with initial exposure from high-intensity ED prescribers. As ED prescribers do not regularly prescribe opioids long term, it is hypothesised that conversion to long-term use may be driven by clinical ‘inertia,’ whereby outpatient clinicians renew previous prescriptions. Our findings suggest that ED physicians may initiate clinical ‘inertia’ due to the fact that approximately 30% of respondents acknowledged that they prescribed opioids to at least 5% of patients who presented with the same problem in the last month. Despite the low number of opioid prescriptions written in EDs, it is important to acknowledge that the EDs are a source of repeat as well as first-time opioid exposures.

Identifying patients who are using EDs for repeat prescriptions is particularly challenging. There is currently no mechanism in Ohio for ED physicians to track patients who move from one ED to another. Although the increased use of Ohio’s prescription drug monitoring programme could assist with this, it is not mandatory for ED physicians in Ohio to review their records if they prescribe for fewer than 7 days.21 Our results highlight the variability of the programmes utilisation, with only 12% of respondents stating they used it for more than 95% of their patients prescribed an opioid in the last month. Without mandatory use of prescription drug monitoring programmes in EDs, which may be administratively cumbersome, tracking patients who move between EDs is beyond the current healthcare systems capabilities.

These findings should be considered in light of multiple limitations. In particular, we note that the survey included self-reported data, which could be influenced by recall or social desirability bias. The survey reported ED medical directors’ perceptions of prescribing practices in their ED, which may not accurately reflect individual-level ED prescribing patterns. These data are also not generalisable outside of Ohio and did not include EDs not affiliated with hospitals. Furthermore, information related to the morphine milligram equivalent per prescription was not obtained, which may provide additional insight into the influence of the guidelines. Also, the introduction of the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines occurred in parallel with other national-based and state-based interventions,5 10 so it is not known if the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines changed prescribers’ views on opioid prescribing or equipped already motivated prescribers with a tool to defend their decision to limit opioid prescriptions. The latter would be consistent with a prior report which indicated that ED physicians used guidelines as a communication tool to protect themselves from liability and patient complaints rather than using them to influence their decision-making process.12

In conclusion, this study showed that the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines have been widely disseminated, with the majority of EDs in Ohio using them to develop hospital-based opioid prescribing policies. The majority of respondents believed that opioid prescribing guidelines have increased the use of the Ohio prescription monitoring programme and have reduced inappropriate opioid prescribing. Although the implementation of the Ohio ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines is promising, further efforts to promote responsible opioid prescribing in other specialties are also required.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the following groups and individuals for their valued role in this evaluation study: American College of Emergency Physicians, Ohio Chapter. Tina L. Turner, State Office of Rural Health Administrator, Office of Health Policy and Performance Improvement, Ohio Department of Health.

Footnotes

Contributors: JP and NJM conceived the study and designed the study protocol in collaboration with MSL, EAH, EW, SC-F, JB, KK and JD-H. JP, RM, CC and ET undertook recruitment and data collection. JP and RM performed the statistical analyses and drafted the article. All authors contributed substantially to its revision. JP took responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Funding: This publication was supported by the grant or cooperative agreement number, 6 NU17CE002738, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Disclaimer: Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Competing interests: MSL reports grants from Ohio Department of Health, during the conduct of the study; grants from Brightview Health Foundation, outside the submitted work. The remaining authors do not report any competing interests.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Cincinnati and at the ODH.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, et al. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:1445–52. 10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Opioid Overdose. Understanding the epidemic. Centers for disease control and prevention. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html (cited 2 Mar 2018).

- 3. Opioid Overdose. Prescription opioid overdose data. Centers for disease control and prevention. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/overdose.html (cited 2 Mar 2018).

- 4. Guy GP, Zhang K, Bohm MK, et al. Vital signs: changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:697–704. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dowell D, Noonan RK, Houry D. Underlying factors in drug overdose deaths. JAMA 2017;318:2295–6. 10.1001/jama.2017.15971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Penm J, MacKinnon NJ, Boone JM, et al. Strategies and policies to address the opioid epidemic: a case study of Ohio. J Am Pharm Assoc 2017;57:S148–S153. 10.1016/j.japh.2017.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Prescription opioid overdose deaths and death rate per 100 000 Population (Age-Adjusted). 2017. http://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/prescription-opioid-overdose-deaths-and-death-rate-per-100000-population-age-adjusted/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Prescription%20Opioid%20Overdose%20Deaths%22,%22sort%22:%22desc%22%7D (cited 2 Mar 2018).

- 8. Winstanley EL, Gay J, Roberts L, et al. Prescription drug abuse as a public health problem in Ohio: a case report. Public Health Nurs 2012;29:553–62. 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2012.01043.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Governor’s Cabinet Opiate Action Team. Ohio guidelines for emergency and acute care facility Opioid and Other Controlled Substances (OOCS) prescribing. Columbus, OH: Ohio Department of Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cantrill SV, Brown MD, Carlisle RJ, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the prescribing of opioids for adult patients in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2012;60:499–525. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beaudoin FL, Straube S, Lopez J, et al. Prescription opioid misuse among ED patients discharged with opioids. Am J Emerg Med 2014;32:580–5. 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kilaru AS, Gadsden SM, Perrone J, et al. How do physicians adopt and apply opioid prescription guidelines in the emergency department? A qualitative study. Ann Emerg Med 2014;64:482–9. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weiner SG, Baker O, Poon SJ, et al. The effect of opioid prescribing guidelines on prescriptions by emergency physicians in Ohio. Ann Emerg Med 2017;70:799–808. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.03.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method: John Wiley & Sons, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weiner SG, Baker O, Rodgers AF, et al. Opioid prescriptions by emergency physicians in Ohio, 2010 to 2014. Pain Med 2016;23:978–89. 10.1093/pm/pnx027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Governor’s Cabinet Opiate Action Team. Ohio guidelines for prescribing opioids for the treatment of chronic non-terminal pain. Columbus, OH: Ohio Department of Health, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Governor’s Cabinet Opiate Action Team. Ohio guideline for the management of acute pain outside of emergency departments. Columbus, OH: Ohio Department of Health, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain--United States, 2016. JAMA 2016;315:1624–45. 10.1001/jama.2016.1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Jena AB. Opioid-Prescribing Patterns of Emergency Physicians and Risk of Long-Term Use. N Engl J Med 2017;376:663–73. 10.1056/NEJMsa1610524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy. Mandatory OARRS registration and requests. http://www.pharmacy.ohio.gov/Documents/Pubs/Special/OARRS/H.B.%20341%20-%20Mandatory%20OARRS%20Registration%20and%20Requests.pdf (cited 2 Mar 2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.