Abstract

Objectives

To examine the knowledge and attitudes of Australian general practitioners (GP) towards medicinal cannabis, including patient demand, GP perceptions of therapeutic effects and potential harms, perceived knowledge and willingness to prescribe.

Design, setting and participants

A cross-sectional survey completed by 640 GPs (response rate=37%) attending multiple-topic educational seminars in five major Australian cities between August and November 2017.

Main outcome measures

Number of patients enquiring about medicinal cannabis, perceived knowledge of GPs, conditions where GPs perceived it to be beneficial, willingness to prescribe, preferred models of access, perceived adverse effects and safety relative to other prescription drugs.

Results

The majority of GPs (61.5%) reported one or more patient enquiries about medicinal cannabis in the last three months. Most felt that their own knowledge was inadequate and only 28.8% felt comfortable discussing medicinal cannabis with patients. Over half (56.5%) supported availability on prescription, with the preferred access model involving trained GPs prescribing independently of specialists. Support for use of medicinal cannabis was condition-specific, with strong support for use in cancer pain, palliative care and epilepsy, and much lower support for use in depression and anxiety.

Conclusions

The majority of GPs are supportive or neutral with regards to medicinal cannabis use. Our results highlight the need for improved training of GPs around medicinal cannabis, and the discrepancy between GP-preferred models of access and the current specialist-led models.

Keywords: primary healthcare, medicinal cannabis, therapeutics, attitude

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to have examined the attitudes and knowledge of Australian general practitioners (GP) about medicinal cannabis.

The study was performed across five major cities in Australia and included a relatively large sample (n=640) of GPs.

Limitations include utilising a survey without established psychometric properties and exclusive recruitment of self-selected GPs from educational seminars who were motivated to complete a survey on medicinal cannabis.

Introduction

There is strong and increasing public support for the use of medicinal cannabis in Australia.1 This support has been a driver of a number of legislative and policy changes enacted over the last two years. These changes have allowed approved companies to cultivate cannabis plants and manufacture cannabis products, and have facilitated legal access to medicinal cannabis for approved patients.2

Despite this, patient access remains complex and highly restricted. Doctors wishing to prescribe medicinal cannabis products must either apply to become authorised prescribers for a class of patients, or apply for access for individual patients under the ‘Special Access Scheme Category B (SAS-B)’3 via the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), a regulatory body for therapeutic goods in Australia. Parallel approvals may also be required from the relevant State or Territory Department of Health. Even with these approvals in place, patients often find available products prohibitively expensive. Moreover, few formal educational training programmes for doctors on the topic of medicinal cannabis have been initiated since the recent legislative changes.

Consequently, few doctors and patients are accessing medicinal cannabis in Australia. Currently, there are only about 33 authorised prescribers, servicing around 190 patients, with a further 513 patients granted access via SAS-B approvals (TGA, personal communication, May 2018). This contrasts with the more mature access schemes of countries such as Canada, where approximately 200 000 patients are serviced.4

Under current schemes, Australian general practitioners (GP) are typically only permitted to prescribe medicinal cannabis if supported by a specialist.3 Nonetheless, GPs are generally the first point of contact for patients enquiring about, or seeking access to, medicinal cannabis. Australian medical bodies have forecasted that patient demand for medicinal cannabis is set to increase.5 With ongoing media coverage fuelling patient expectations regarding therapeutic efficacy and cannabis access,6 GPs may be forced into the role of gatekeepers despite having limited knowledge and training in the field.

The attitudes of Australian GPs towards medicinal cannabis are unknown. Statements from peak medical bodies such as the Royal Australasian College of Physicians,7 Australian Medical Association, and the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists’ Faculty of Pain Management generally advise caution on the basis of limited evidence for efficacy and safety.5 8–10 Surveys from other countries suggest that clinicians are generally more reticent towards medicinal cannabis than the general public, particularly in the USA,11 12 with concerns centred on limited evidence for efficacy and adverse effects, including abuse and dependence.11–13 Nevertheless, recent analyses suggest that the majority of GPs and specialists internationally support the use of medicinal cannabis for specific conditions.14

This article describes the results of a survey of Australian GPs around medicinal cannabis issues, including their clinical experiences, perceived knowledge, and beliefs about its regulation, safety, indications for use and the preferred role of GPs in its prescription.

Methods

Printed surveys were distributed at one-day general practice educational seminars held in five major Australian cities (Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth) between August and November 2017. All GPs and GP registrars were eligible to participate (n=1728). Seminars covered a range of topics relevant to general practice with around 18 different topics covered on the day in consecutive 20–30 min presentations. GPs and GP registrars received professional education points for attending the seminars. One of the authors (ISM) spoke on the topic of medicinal cannabis at each event, but surveys were completed and collected prior to this presentation. During the opening of each HealthEd seminar, participants were informed that the survey and its information and consent form were located in their conference satchel. Participants were instructed to turn in their surveys, before afternoon tea, into drop boxes at the conference.

The survey was devised specifically for use in this study, and thus had not been psychometrically validated. Questions were reviewed by an advisory group of GPs to ensure appropriate wording and clarity (see online supplementary material for copy of full survey). Participants first completed a series of closed questions on demographics, vocational experience (years in practice, registrar status, hours per week) and practice characteristics (size, state/territory, geographical classification). The survey proper consisted of 46 items on topics related to medicinal cannabis including clinical experience (4 items); perceived knowledge (5 items); concerns and awareness about safety and efficacy (18 items); appropriate indications for use (14 items); and views on the role of GPs and specialists in its prescribing (5 items).

bmjopen-2018-022101supp001.pdf (647.2KB, pdf)

Participants rated the extent to which they agreed with 44 statements on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree; 5=strongly agree). There were also two multiple-choice questions concerning patient demand and prescribing preferences (role of GPs/specialists). The latter question was only introduced after the first seminar (included in 73% of completed surveys; excludes respondents from the Sydney event). A space for open-ended comments was provided at the end of the survey.

Results were summarised using descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage of valid responses). Likert scale responses were generally collapsed into three categories: agree, neutral and disagree. Open-ended comments were reviewed for common themes. A composite score for Perceived Knowledge was created by summing scores from five knowledge-related questions. Age, sex and perceived knowledge were tested as potential predictors of views on medicinal cannabis availability (‘medicinal cannabis should currently be available on prescription for certain indications’; 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree) using separate ordinal logistic regression analyses. Χ2 tests were used to compare the demographic characteristics of our sample to the Australian population of GPs.15

One section of the questionnaire asked whether GPs support the use of medicinal cannabis in 14 different medical conditions. To assess whether their support was consistent with current evidence for efficacy, each indication was categorised as having either ‘Good Evidence for Efficacy’ (spasticity in multiple sclerosis (MS), intractable epilepsy, chronic cancer pain, chronic non-cancer pain, neuropathic pain, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV)) or ‘Poor Evidence for Efficacy’ (anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, cachexia, cancer/antitumour effects, agitation in dementia and insomnia) based on two recent authoritative reviews,16 17 and levels of support expressed compared with this evidence base. The evidence for ‘palliative care’ was not assessed in either review and was thus excluded for the purposes of this analysis. Further, GP respondents were categorised as having either ‘Good Perceived Knowledge’ or ‘Poor Perceived Knowledge’ using a cut-off score of 15 on the composite score for Perceived Knowledge (the midpoint between the lowest (=5) and highest (=25) possible scores for the five questions relating to self-knowledge). Χ2 tests were used to assess whether GPs with Good Perceived Knowledge expressed greater support for specific indications than those with Poor Perceived Knowledge. Bonferroni correction was used to control for these multiple comparisons.

Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, V.24.0 (IBM), and graphs were created using GraphPad Prism V.7.02 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA).

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in this study.

Results

Demographic data

Demographic and practice details of the 640 participants are shown in table 1. The majority of participants were female (67.3%), aged between 35 and 64 years (77.5%), and residing in Victoria (30.3%) and New South Wales (27.5%). Over half of respondents had been practising for >15 years (56.7%), worked >30 hours/week (63.4%) and serviced metropolitan areas (60.3%). Only 8.2% were in single-GP practices and 7.9% were registrars.

Table 1.

Demographic and practice characteristics of GPs in this study, and all GPs in Australia

| GP survey (n=640) | Australia (n=34 606)15 | P values (X2 test) | ||

| n | Valid % | % | ||

| Age (n=640) | <0.001 | |||

| <35 | 57 | 8.9 | 13.4 | |

| 35–44 | 134 | 20.9 | 24.9 | |

| 45–54 | 177 | 27.7 | 24.9 | |

| 55–64 | 185 | 28.9 | 23.1 | |

| 65+ | 87 | 13.6 | 13.7 | |

| Sex (n=636) | <0.001 | |||

| Female | 428 | 67.3 | 44.7 | |

| GP registrar (n=611) | 0.08 | |||

| Yes | 48 | 7.9 | 10.0 | |

| State/territory (n=627) | 0.001 | |||

| New South Wales | 175 | 27.9 | 30.6 | |

| Victoria | 193 | 30.8 | 24.1 | |

| Queensland | 129 | 20.6 | 21.7 | |

| South Australia | 81 | 12.9 | 7.8 | |

| Western Australia | 39 | 6.2 | 10.2 | |

| Geographical area (n=611) | ||||

| Metropolitan | 381 | 62.4 | 68.2 | 0.01 |

| Regional | 206 | 33.7 | 28.0 | |

| Remote | 24 | 3.9 | 3.9 | |

| Years as GP (n=637) | ||||

| <2 | 38 | 6.0 | ||

| 2–5 | 90 | 14.1 | ||

| 6–15 | 148 | 23.2 | ||

| 16–25 | 136 | 21.4 | ||

| 26+ | 225 | 35.3 | ||

GP, general practitioner.

Experience, practice and general attitudes

A majority of GPs (61.5%) had experienced at least one patient enquiry regarding medicinal cannabis in the prior 3 months, with 7.5% reporting more than five enquiries. When considering GPs working >30 hours/week, the proportion with at least one enquiry increased to 69.0% and 11.8% received more than five enquiries (table 2).

Table 2.

Reported number of patient enquiries about medicinal cannabis in the prior 3 months, for all respondents and those working over 30 hours/week, on average

| Number of patients enquiring | All respondents (n=615) | Respondents >30 hours/week (n=391) |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| 0 | 237 (38.5) | 116 (31.0) |

| 1 | 159 (25.9) | 90 (24.1) |

| 2–5 | 173 (28.1) | 124 (33.2) |

| 6–10 | 33 (5.4) | 32 (8.6) |

| >10 | 13 (2.1) | 12 (3.2) |

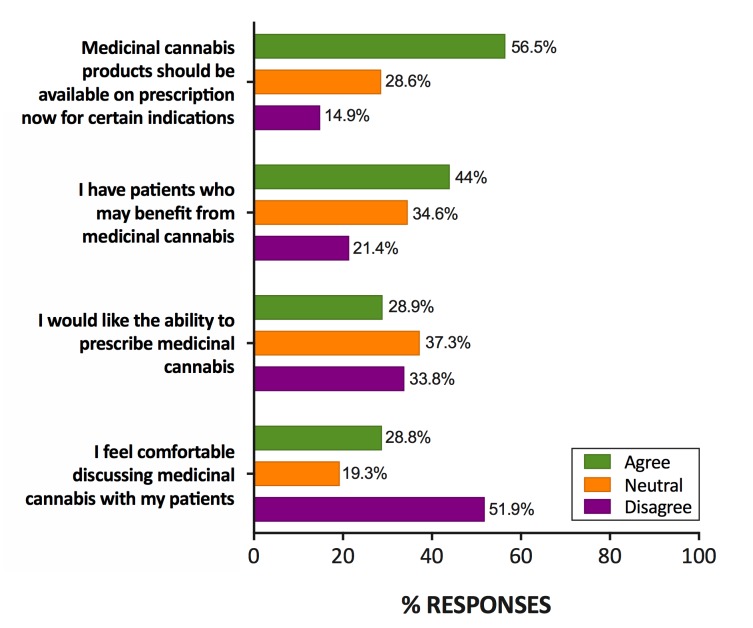

More than half of GPs agreed with the statement that medicinal cannabis should currently be available on prescription for certain indications (strongly agree: 19.6%, n=125/637; slightly agree: 36.9%), while 14.9% disagreed (figure 1). GPs were more likely to agree if they were older (χ2(4)=25.63, p<0.001) and had greater perceived knowledge (χ2(2)=5.54, p=0.02), but there was no difference between sexes (χ2(1)=2.55, p=0.11).

Figure 1.

Attitudes and clinical experiences of general practitioners with respect to medicinal cannabis, n=632–637, valid percentage.

More GPs agreed that they had patients who would benefit from medicinal cannabis (44.0%, n=280/636) than disagreed (21.4%), with 34.6% expressing a neutral opinion (figure 1). Conversely, fewer respondents agreed that they would like to be able to prescribe medicinal cannabis (28.9%, n=183/633) than disagreed (33.8%), again with a high number of neutral responses. Approximately half of respondents (n=51.9%; n=328/632) did not feel comfortable discussing medicinal cannabis with their patients.

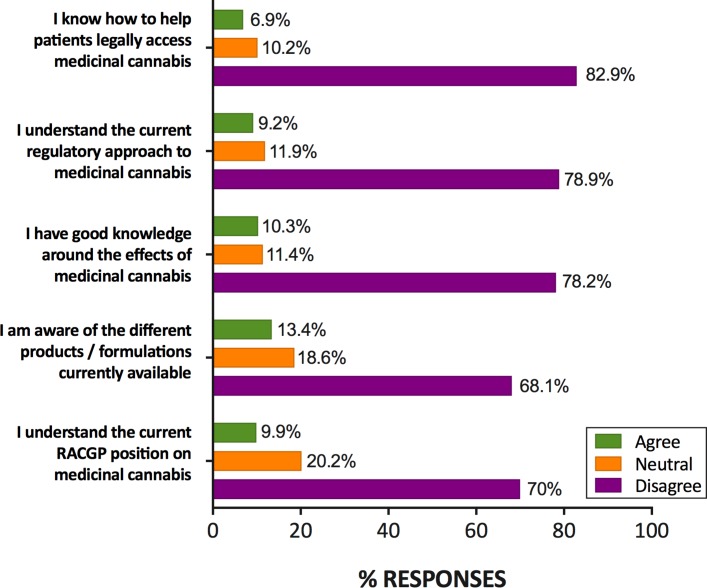

Perceived knowledge

GPs generally rated their knowledge of medicinal cannabis as poor (figure 2). On all five knowledge-related items, over two-thirds of respondents disagreed that they had knowledge of the topic in question. Notably, 65.4% (n=417/638) ‘strongly disagreed’ that they knew how to access medicinal cannabis for patients, and more than half ‘strongly disagreed’ that they knew about available products (55.5%, n=354/638) or the current regulatory approach (57.8%, n=370/630). According to their own self-ratings, 543 (86%) GPs had Poor Perceived Knowledge (<15/25 composite score) while 88 (14%) GPs were categorised as having Good Perceived Knowledge (≥15/25 composite score).

Figure 2.

Ratings of general practitioners on knowledge-related items, n=636–640, valid percentage. RACGP, Royal Australian College of General Practitioners.

Respondents were more likely to endorse an access model permitting prescribing by trained and accredited GPs (78.6% agree, n=503/640), or by GPs in a ‘shared care’ arrangement with a specialist (63.2%, n=401/634) than specialist-only prescribing (44.6%, n=283/634). When asked to choose one preferred model, 41.2% (n=164/398; note this question was not included in the survey used at the first seminar in Sydney) indicated trained GPs as their preferred prescriber, followed by shared care (29.6%). Specialist-only prescribing was preferred by 14.6% of respondents, while only 12.1% preferred that all GPs have the right to prescribe, regardless of training.

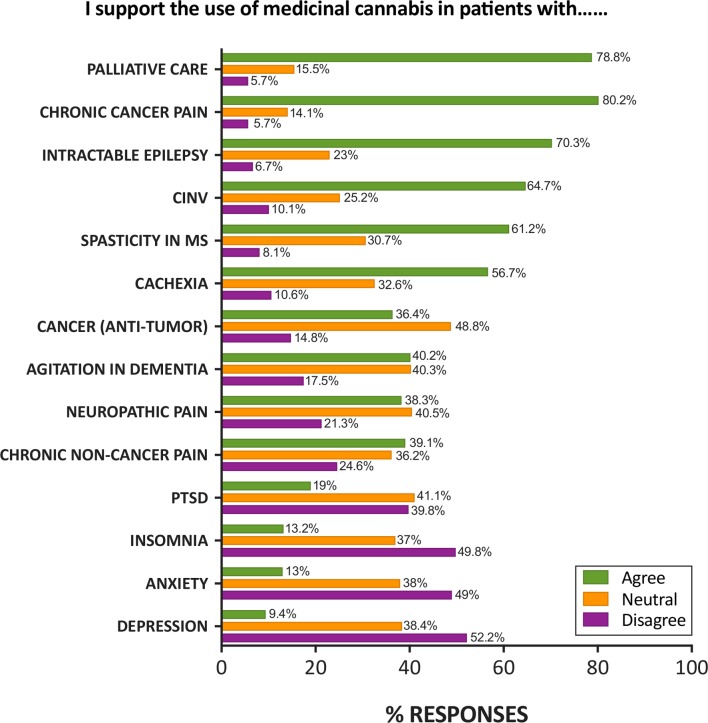

Indications for use and evidence for efficacy

Almost half of respondents (48.0%, n=305/635) were neutral as to whether there was sufficient overall scientific evidence for the efficacy of medicinal cannabis, with 22.8% supporting the statement. Those who agreed that medicinal cannabis should be available on prescription had higher endorsement of the statement than those who disagreed (40.2% vs 11.7%). GPs supported the use of medicinal cannabis in chronic cancer pain (80.2% agree, n=506/631), palliative care (78.8%, n=494/627) and intractable epilepsy (70.3%, n=441/627; figure 3). Use in chronic non-cancer pain and neuropathic pain was endorsed by only 39.1% (n=246/629), and 38.3% (n=241/630) of respondents, respectively, with a high degree of neutrality. Less than 15% of GPs supported use in anxiety, insomnia or depression with a majority of GPs declining to support use in these conditions (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Support for use of medicinal cannabis in different conditions, n=627–632, valid percentage. CINV, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting; MS, multiple sclerosis; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

GPs with Good Perceived Knowledge of medicinal cannabis were more likely to support its use in neuropathic pain (52.9%) and chronic non-cancer pain (54%) than GPs with Poor Perceived Knowledge (35.6% and 36.4%, respectively) (neuropathic pain, X2(2, n=620)=9.9, p=0.007; chronic non-cancer pain, X2(2, n=620)=11.2, p=0.004). No other significant differences between GPs’ perceived knowledge level and their support for specific medical conditions were identified.

Perceived features and adverse effects of medicinal cannabis

Approximately two-thirds of respondents disagreed with the statement that medicinal cannabis was no different from street cannabis (43.9% strongly disagree; n=271/640; 20.5% slightly disagree), while 14.4% agreed.

The side effects of medicinal cannabis endorsed by more than half of respondents included driving impairment (64.9% agree, n=408/629), adverse effects on the developing brain (58.4%, n=366/627), cognitive impairment (56.5%, n=356/630) and addiction and dependence (56.3%, n=353/627); psychosis was endorsed by 49.9% (n=313/627).

Overall, 27.7% of respondents (n=177/637) agreed that they would not prescribe medicinal cannabis due to the risk of abuse and dependence, and 19.8% (n=127/638) due to other side effects. These proportions were higher among GPs who disagreed with the availability of medicinal cannabis on prescription (58.1% and 44.2%, respectively) and among those who disagreed that they would like to prescribe medicinal cannabis (47.6% and 34.6%, respectively).

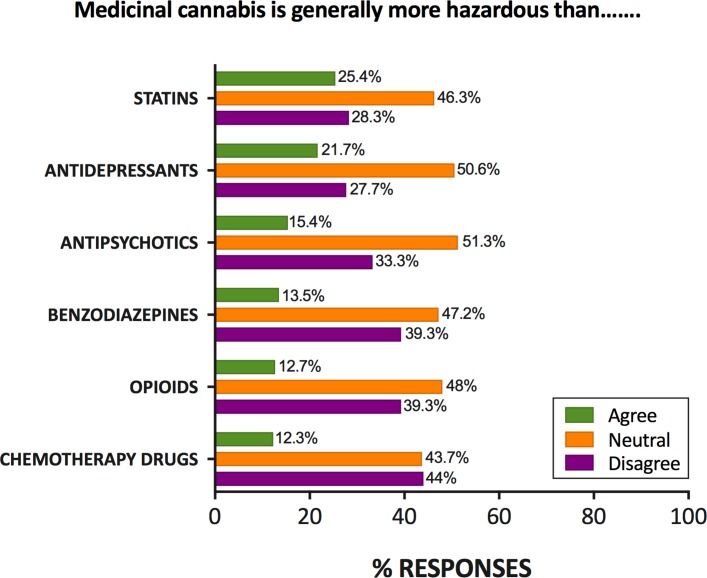

A high proportion of GPs were neutral with respect to whether medicinal cannabis was more hazardous than other prescription medicines (range: 43.7%–51.3%; figure 4). Of the remaining responses, a majority believed that medicinal cannabis was safer than chemotherapy drugs (78.1%, n=278/356), opioid analgesics (75.6%, n=248/328), benzodiazepines (74.5%, n=248/333) and antipsychotics (68.3%, n=209/306), and over 50% for antidepressants and statins.

Figure 4.

Ratings of relative hazards of medicinal cannabis compared with other prescription medicines, n=627–632, valid percentage.

Open-ended responses

Of the 156 open-ended responses, 48.1% concerned the participant’s lack of knowledge about medicinal cannabis and/or the desire for training. Other common themes included the need for more evidence of efficacy (n=18) and concerns about harms (n=19), namely abuse and dependence (n=10), cannabis-seeking for recreational use (n=5), repeating mistakes made with opioids/benzodiazepines (n=6) and other side effects (n=4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study of the experiences, attitudes and knowledge of Australian GPs regarding medicinal cannabis. The survey demonstrates that many GPs have fielded recent enquiries about medicinal cannabis from their patients, yet half were not comfortable dealing these enquiries and most felt poorly informed about medicinal cannabis and its current availability, regulation and uses. This perceived lack of knowledge was strongly conveyed in the open-ended comments, as well as broadly reflected in the large number of neutral responses to questions regarding therapeutic and adverse effects.

In agreement with clinician surveys in the USA,11 12 Australian GPs were somewhat conservative in their attitudes about medicinal cannabis: slightly less than 60% agreed that medicinal cannabis should be available on prescription compared with approximately 85% of the general Australian population.1 This rate, however, has somewhat risen since previous surveys, with just under 30% of Australian GPs reporting that cannabis should be available for medicinal purposes in 201218. This suggests a possible shift in attitudes over time as increasing community support has driven a number of legislative and policy changes for greater patient access and clinical trials in Australia. In the present survey, GPs were generally more supportive of use of medicinal cannabis in conditions with a stronger evidence base (such as spasticity in MS, CINV) and/or where few effective alternatives exist (palliative care, cancer pain, intractable epilepsy).16 This also aligns with the indications for use suggested by various state governments.19 20 By contrast, less than 40% of all GPs supported use of medicinal cannabis in chronic non-cancer pain. This may reflect the mixed findings regarding efficacy for this indication,16 21 concerns about inappropriate use, particularly in light of the problems associated with prescription opioids,22 and the lack of endorsement by Australian government and medical organisations.10 19 Similarly, concerns about limited evidence for efficacy, risk of worsening illness and inappropriate use may underlie the very low support for use in depression, anxiety and insomnia.16 19 It is somewhat troubling that these latter indications were among the most common reasons for illegal use of cannabis for medicinal purposes in a survey of more than 1700 current users in the Australian community (Lintzeris et al, in press).

Although GPs exhibited responses that suggested at least some familiarity with the scientific and clinical literature, perceived knowledge about the effects, products and process of accessing medicinal cannabis was generally very low. Less than 10% of GPs in our survey reported understanding the current regulations concerning medicinal cannabis or how it can be accessed for patients. It is well known that poor knowledge and low levels of comfort discussing issues with patients are barriers to optimal patient care.12 23 Provision of continuing medical education and guidelines on the regulatory, pharmacological and clinical aspects of medicinal cannabis are vital for equipping GPs to manage patients effectively.

One surprising aspect of this survey was how GPs rated medicinal cannabis relative to other common classes of prescription medicines. Of those expressing a non-neutral opinion (approximately 50%), about three-quarters rated medicinal cannabis as less harmful than opioids and benzodiazepines, and notably, just over half rated it less harmful than antidepressants and statins. This perception of the relative safety of medicinal cannabis compared with opioids and benzodiazepines may reflect its negligible rate of mortality and relatively mild dependence and withdrawal syndrome.24 Nonetheless, cannabis can clearly produce dependence; recent estimates suggest that there are over 45 000 treatment episodes each year for Australians seeking control over their cannabis use.25 Concerns about abuse, misuse and dependence were an identified theme of the open-ended comments in our survey. Moreover, almost half of the GPs who did not want to be able to prescribe cannabis cited the risk of abuse and dependence as a primary concern.

Although there was a high degree of neutrality with respect to the desire of GPs to prescribe medicinal cannabis, the vast majority supported a model of prescribing in which GPs played a significant role. A model in which trained, accredited GPs could prescribe without specialist input received the strongest support, followed by GP prescribing in a ‘shared care’ arrangement with a specialist. This contrasts with the current model in Australia, where prescribing is conducted by specialists, although shared care arrangements are theoretically possible.3 Although specialist-only prescribing may provide greater restrictions on use, the extension of prescribing rights to appropriately trained GPs arguably enables more holistic patient care, more frequent monitoring, better detection of adverse effects and more timely treatment.26 It is notable that GPs are empowered to prescribe, or permit access to, medicinal cannabis products in countries such as Canada and the USA,12 23 27 and the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners recently updated their position statement to explicitly endorse a direct role for GPs in medicinal cannabis access.28

The strength of the study is the unique nature of the survey and the relatively large sample size enabled by accessing the GPs attending popular educational events. While our response rate of 37% appears relatively low, it exceeds typical published response rates of GP surveys.29 Limitations include the sole recruitment of self-selected GPs from HealthEd seminars, reliance on self-report of service provision and utilising a survey without established psychometric properties. Furthermore, the survey respondents differed on a number of demographic and practice characteristics to the general population of GPs in Australia, suggestive of a non-representative sample. For instance, there was a disproportionate representation of female GPs in our study, which may be due to a tendency for greater survey response from women relative to men in general.30 Finally, the findings cannot be generalised to other countries such as the USA and Canada, among others, where access to medicinal cannabis is not so strictly regulated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the HealthEd seminar organisers, in particular, Christie Ho, who was responsible for preparing the questionnaire and ensuring effective recruitment. We are grateful to Eila McGregor for research assistance. We also thank Dr Michael Bowen for assistance with statistical analysis.

Footnotes

EAK and AS contributed equally.

Contributors: RM, ISM, EAK, AS and NE conceived the study. ISM collected the data. EAK, AS and ISM conducted the data analysis and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by The Lambert Initiative for Cannabinoid Therapeutics at The University of Sydney.

Competing interests: ISM is Academic Director of The Lambert Initiative and an National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Principal Research Fellow and receives research funding from the Australian Research Council and NHMRC. He is involved in an NHMRC-funded clinical trial using the cannabis extract, nabiximols (Sativex). This survey was conducted at seminars run by HealthEd. RM is the CEO of HealthEd, and ISM received honoraria and travel expenses from HealthEd for lectures conducted at these events. All other authors have no competing interests to declare.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for the survey was granted by The University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (2017/692).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2016: Detailed findings. Drug Statistics Series No. 31. 2017; https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/15db8c15-7062-4cde-bfa4-3c2079f30af3/21028.pdf.aspx?inline=true (accessed Nov 2017).

- 2. Department of Health. Medicinal cannabis products: overview of regulation. Canberra: Therapeutic Goods Administration, 2017; https://www.tga.gov.au/medicinal-cannabis-products-overview-regulation (accessed Nov 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Department of Health. Access to medicinal cannabis products: steps to using access schemes. Canberra: Therapeutic Goods Administration, 2017; https://www.tga.gov.au/access-medicinal-cannabis-products-steps-using-access-schemes (accessed Dec 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4. Health Canada. Cannabis for Medical Purposes (FY 2017-18) - Licensed Producers: Monthly Data Ontario: Health Canada. Market Data. 2017; https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/medical-use-marijuana/licensed-producers/market-data.html (accessed Nov 2017).

- 5. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). RACGP Position statement: Medicinal use of cannabis products. Melbourne: RACGP, 2016; https://www.racgp.org.au/support/policies/clinical-and-practice-management/racgp-position-statement-medicinal-use-of-cannabis-products/ (accessed Oct 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gates P, Todd S, Copeland J. Survey of Australian’s knowledge, perception and use of cannabis for medicinal purposes. J Addict Prev 2017;5:10. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Martin JH, Bonomo Y, Reynolds AD. Compassion and evidence in prescribing cannabinoids: a perspective from the Royal Australasian College of Physicians. Med J Aust 2018;208:107–9. 10.5694/mja17.01004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bartone T. Medicinal cannabis: still a lot of misinformation. Australian Medical Association, 2017; https://ama.com.au/ausmed/medicinal-cannabis-%E2%80%93-still-lot-misinformation (accessed Oct 26 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnson C. Green light for medicinal cannabis but Australian Medical Association says proceed with caution. Australian Medicine 2017;29:9. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA). Statement on “medicinal cannabis” with particular reference to its use in the management of patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Melbourne: ANZCA, Faculty of Pain Medicine, 2015. http://fpm.anzca.edu.au/documents/pm10-april-2015.pdf (accessed Nov 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 11. Charuvastra A, Friedmann PD, Stein MD. Physician attitudes regarding the prescription of medical marijuana. J Addict Dis 2005;24:87–93. 10.1300/J069v24n03_07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kondrad E, Reid A. Colorado family physicians' attitudes toward medical marijuana. J Am Board Fam Med 2013;26:52–60. 10.3122/jabfm.2013.01.120089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Crowley D, Collins C, Delargy I, et al. Irish general practitioner attitudes toward decriminalisation and medical use of cannabis: results from a national survey. Harm Reduct J 2017;14:4 10.1186/s12954-016-0129-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adler JN, Colbert JA. Medicinal use of marijuana — polling results. N Engl J Med 2013;368:22 866-868 10.1056/NEJMclde1305159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Department of Health. General Practice Workforce Statistics – 2001-02 to 2016-17. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2017; http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/General+Practice+Statistics-1 (accessed Nov 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: The current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2017; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK423845/ (accessed Nov 2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2015;313:2456–73. 10.1001/jama.2015.6358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Norberg MM, Gates P, Dillon P, et al. Screening and managing cannabis use: comparing GP’s and nurses' knowledge, beliefs, and behavior. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2012;7:31 10.1186/1747-597X-7-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Queensland Health. Clinical Guidance: for the use of medicinal cannabis products in Queensland. Brisbane: Queensland Government, 2017; https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0023/634163/med-cannabis-clinical-guide.pdf (accessed Nov 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Victorian Law Reform Commission (VLCR). Medicinal cannabis: report. Melbourne: VLRC, 2015. http://lawreform.vic.gov.au/projects/medicinal-cannabis/medicinal-cannabis-report-pdf (accessed Nov 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nugent SM, Morasco BJ, O’Neil ME, et al. The effects of cannabis among adults with chronic pain and an overview of general harms: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:319–31. 10.7326/M17-0155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA). "Medicinal" cannabis: Where’s the evidence? Victoria: ANZCA Bulletin, 2016; www.anzca.edu.au/documents/anzca-bulletin-september-2016.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 23. Carlini BH, Garrett SB, Carter GT. Medicinal cannabis: a survey among health care providers in Washington State. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2017;34:85–91. 10.1177/1049909115604669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, et al. Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse. Lancet 2007;369:1047–53. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia 2015–16: key findings, Table S2. Canberra: AIHW, 2017; https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/alcohol-other-drug-treatment-services/aodts-2016-17-key-findings/data (accessed Nov 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 26. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). Reports, submissions and outcomes GP prescribing rights for Isotretinoin. Melbourne: RACGP, 2014. https://www.racgp.org.au/yourracgp/news/reports/201405isotretinoin (accessed Nov 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ziemianski D, Capler R, Tekanoff R, et al. Cannabis in medicine: a national educational needs assessment among Canadian physicians. BMC Med Educ 2015;15:52 10.1186/s12909-015-0335-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). The regulatory framework for medicinal use of cannabis product: position statement. Melbourne: RACGP, 2018; https://www.racgp.org.au/download/Documents/Policies/Health%20systems/Regulatory-framework-for-medicinal-use-of-cannabis-products-.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bonevski B, Magin P, Horton G, et al. Response rates in GP surveys - trialling two recruitment strategies. Aust Fam Physician 2011;40:427–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cull WL, O’Connor KG, Sharp S, et al. Response rates and response bias for 50 surveys of pediatricians. Health Serv Res 2005;40:213–26. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00350.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022101supp001.pdf (647.2KB, pdf)