Abstract

Introduction

The burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD) is rapidly increasing in developing countries, however access to cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention (CR/SP) in these countries is limited. Alternative delivery models that are low-cost and easy to access are urgently needed to address this service gap. The objective of this study is to investigate whether a smartphone and social media-based (WeChat) home CR/SP programme can facilitate risk factor monitoring and modification to improve disease self-management and health outcomes in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD), after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) therapy.

Methods and analysis

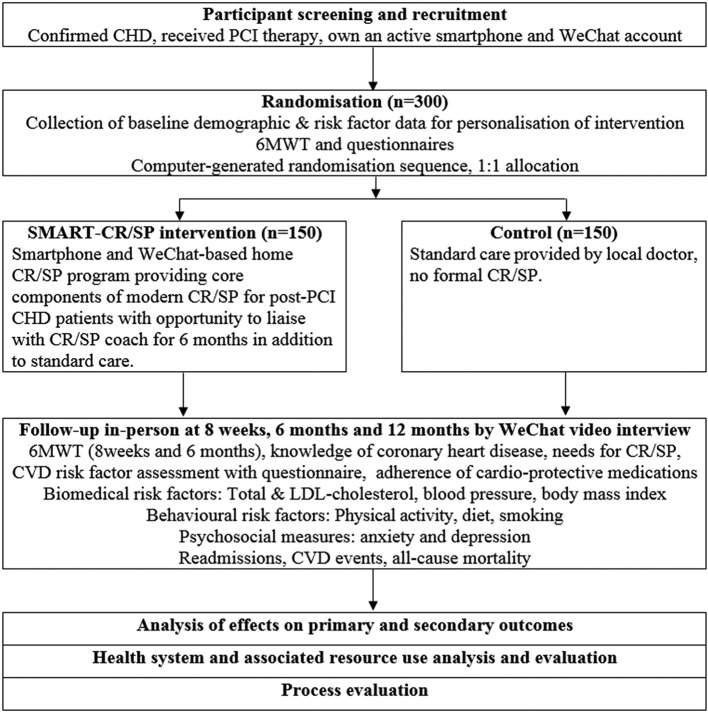

We propose a single-blind, randomised controlled trial of 300 patients post-PCI with follow-up over 12 months. The intervention group will receive a smartphone-based and WeChat-based CR/SP programme providing education and support for risk factor monitoring and modification. SMART-CR/SP incorporates core components of modern CR/SP: physical activity tracking with interactive feedback and goal setting; education modules addressing CHD understanding and self-management; remote blood pressure monitoring and strategies to improve medication adherence. Furthermore, a dedicated data portal and a CR/SP coach will facilitate individualised supervision and counselling. The control group will receive usual care but no formal CR/SP programme. The primary outcome is change in exercise capacity measured by 6 minute walk test distance. Secondary outcomes include knowledge and awareness of CHD, risk factor status, medication adherence, psychological well-being and quality of life, major cardiovascular events, re-hospitalisations and all-cause mortality. To assess the feasibility and patients’ acceptance of the intervention, a process evaluation will be performed at the conclusion of the study.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was granted by both the Human Research Ethics Committee of Fudan University Zhongshan Hospital (HREC B2016-058) and Curtin University Human Research Ethics Office (HRE2016-0120). Results will be disseminated via peer-reviewed publications and presentations at conferences.

Clinical trial registration number

ChiCTR-INR-16009598; Pre-results.

Keywords: coronary heart disease, cardiac rehabilitation, secondary prevention, social media, wechat

Strengths and limitations of the study.

We propose an innovative social media-based cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention (CR/SP) programme to deliver community-based support for patients with coronary heart disease, after hospitalisation for percutaneous coronary intervention therapy. To our knowledge, this will be the first study to evaluate a CR/SP programme provided exclusively via social media.

To inform the design of the intervention, end-user surveys and focus group discussions were undertaken to identify patients’ needs related to CR/SP.

This will be a single-centre study, which may limit the generalisation and application of the study results to a broader population. However, the large geographic, cultural and socioeconomic diversity of patients admitted at the study hospital may help to reduce this potential bias.

The study is limited to patients with smartphones and internet access.

It is possible that the increased exposure to the health system experienced by participants in the experimental group will influence their behaviour, independent of the effects of the mHealth intervention.

Introduction

The rapid economic growth and industrialisation of China over the past three decades has been paralleled by a growing epidemic of coronary heart disease (CHD). It is estimated that there are over 11 million Chinese people with this disease, a figure expected to increase steadily in the next few decades.1–3 In 2015, over 560 000 cases of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), a common treatment for CHD, were performed in mainland China.1 People with established CHD are at high risk of recurrent cardiac events4 which place a significant burden on healthcare services. However, these events can be reduced by up to half with effective secondary prevention, such as adherence to cardioprotective medication and lifestyle modification.5

Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention (CR/SP) are systematic, evidence-based processes that facilitate the delivery of preventive therapies and improve patient outcomes after a cardiovascular event. Participation in CR/SP programmes can reduce mortality by up to 25%, improve quality of life and reduce cardiovascular risk factor burden.6 7 However, despite the well-established benefits, CR/SP services are still grossly underutilised globally. Data from developed countries, such as the United States and Australia, reported patient participation rates of between 30% and 45%, with high dropout rates of between 40% and 55%.8–12 In low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), access to CR/SP services remains very low, with less than a quarter of countries having CR/SP programmes.13 14 In China, despite recent advances in the medical management of CHD, very few patients currently receive CR/SP services.15 16 This may be due in part to the challenges associated with establishing traditional models of CR/SP in the Chinese healthcare environment, such as the lack of specific funding, staff education and training, and reimbursements for participating patients.15–17 Accordingly, there is a need for innovative strategies to implement this evidence-based therapy in China.

Internet and smartphone-based interventions have recently been shown to be effective alternative methods for delivering rehabilitation and secondary prevention programmes for people with CHD.18–21 Especially in the context of risk factor modification and behaviour change.22–24 The rapid increase in smartphone and social media users in China has created a strong platform for the delivery of CR/SP services via these media. For example, it is reported that there are over 800 million active users of WeChat, a popular social media site in China.25 However, there are currently no studies that have examined the feasibility and efficacy of using smartphones and social media to provide rehabilitation and secondary prevention services for the Chinese population. A recent study that used WeChat to support weight loss has shown positive results. In this study, participants who were more active in the WeChat-based weight loss programme lost more weight, highlighting that social media may offer a promising new approach to managing chronic health conditions.26

It is in this context that we have developed the smartphone and WeChat-based home cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention (SMART-CR/SP) study.

Methods and analysis

Study design

SMART-CR/SP will be a single-blind, two-arm, parallel, randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effects of CR/SP delivered via smartphone and WeChat on patient exercise capacity, knowledge and awareness of the disease, medication adherence, blood pressure, lipid profile, quality of life and clinical outcomes (figure 1). The protocol conforms to the SPIRIT 2013 statement and the intervention is described in accordance with the CONSORT-EHEALTH checklist.27–29

Figure 1.

Randomised controlled trial design and flowchart. The control group will receive usual care but no formal CR/SP. The intervention group will receive a smartphone and WeChat-based CR/SP programme providing education and support for risk factor monitoring and modification. CHD, coronary heart disease; CR/SP, cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention; CVD, cardiovascular disease; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; 6MWT, 6 min walk test; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Eligibility and recruitment

Patients between the ages of 18 and 70 years with a diagnosis of CHD, including myocardial infarction, unstable or stable angina, who are treated with PCI therapy during their current admission will be eligible for inclusion. All participants will be required to personally own an operational smartphone, have an active WeChat account and sufficient Chinese language proficiency.

Exclusion criteria include: contra-indications to exercise rehabilitation (eg, untreated ventricular tachycardia, severe heart failure, uncontrolled hypertension or hypotension, significant exercise limitations), an inability to operate a smartphone for the purpose of the trial (eg, vision, hearing, cognitive or dexterity impairment), lack of internet access at place of residence or having pre-existing comorbid disease with a life expectancy of <1 year.

Recruitment will occur during hospital admission at Fudan University Zhongshan Hospital in Shanghai. The hospital is a pre-eminent public hospital in Eastern China, servicing a culturally and socioeconomically diverse population from across the nation. Patients admitted with CHD, and who receive PCI therapy during their admission, will be screened and those meeting the inclusion criteria will be invited to participate in the study. A face-to-face interview will be arranged for patients who express an interest in the trial, and formal written consent will be obtained from candidates who agree to participate.

Sample size calculation

A 25 m improvement in the 6 min walk test (6MWT) is considered to be clinically meaningful.30–32 Thus, to detect a minimal clinically important difference of 25 m for the 6MWT with 90% power (type I error=5%, two-sided test), assuming a SD of 60 m,18 we will require a total sample size of 242 across both arms of the study. Assuming, an estimated 20% loss to follow-up, we plan to recruit a total of 300 participants.

Randomisation and blinding

Following provision of consent, participants will be randomised in a 1:1 fashion to a smartphone and WeChat-based cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention programme (SMART-CR/SP) group, or a usual care group by using the random allocation sequences generated from SAS software. The SMART-CR/SP programme will be initiated within 2 weeks of participant discharge following PCI therapy. Participants will be informed of their group allocation through a single WeChat message. Additionally, participants in the intervention group will receive their first cartoon-format WeChat article, illustrating the SMART-CR/SP programme, to familiarise them with the system and mobile technologies involved. Additional technology training will be provided if required by the participant. Research personnel involved in participants’ assessments will be blinded to treatment allocation.

Control (usual care) group

Participants in the usual care group will receive standard care as provided by their community doctors and cardiologists after hospital discharge. In China, current post-PCI care involves brief inpatient health education provided by a ward nurse, medication management and ad hoc follow-up visits to a cardiologist or other healthcare providers according to the patient’s self -assessment of their own cardiovascular health.

Intervention group

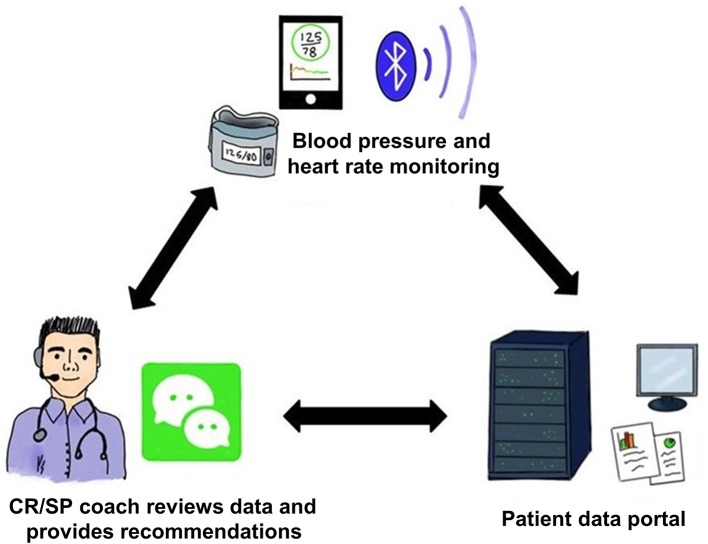

In addition to usual care, participants in the SMART-CR/SP group will receive an 8-week comprehensive smartphone and WeChat-based home CR/SP programme providing core components of guideline advocated CR/SP for post-PCI patients with CHD,33 34 followed by a 16 week ‘step-down’ programme. Figure 2 provides a pictorial representation of the interactive system.

Figure 2.

Components of the Smart-CR/SP system. SMART-CR/SP incorporates core components of modern CR/SP: physical activity tracking with interactive feedback and goal setting; education modules addressing CHD understanding and self-management; remote blood pressure monitoring and strategies to improve medication adherence. Furthermore, a dedicated data portal and a CR/SP coach will facilitate individualised supervision and counselling. CHD, coronary heart disease; CR/SP, cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention.

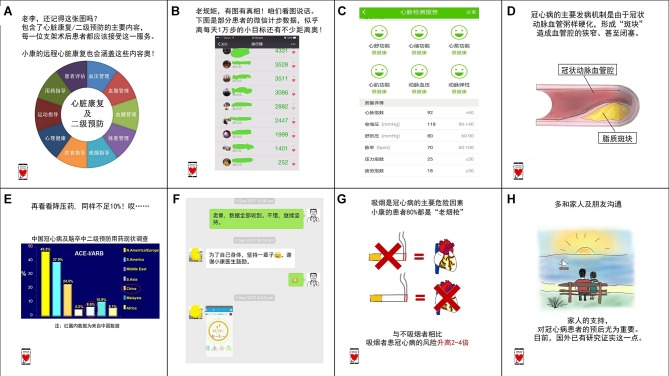

Cardiac health education

A culturally appropriate and user-friendly WeChat-based cardiac health education system has been developed for this trial, which consists of 32 episodes of cartoon-format CHD educational articles, covering a broad range of cardiovascular health education topics relevant to post-PCI patients with CHD (figure 3). In the first 8 weeks, participants will receive four WeChat educational articles per week. Each of the articles will introduce one key educational topic using a short interactive story involving dialogue between a patient and cardiologist avatar that is illustrated by 20–30 cartoon drawing slides. In the ‘step-down’ programme, two cartoon drawing slides with a key motivational message attached to each will be sent to participants’ WeChat account every week. The WeChat articles/slides and messages will be sent during random working hours on random weekdays from an official WeChat account (avatar name: Dr Kang: an abbreviation of ‘rehabilitation’ in Chinese). Box 1 shows the content of the cardiac health education.

Figure 3.

WeChat-based CR/SP system interface depicting health education (A), physical activity tracking (B), blood pressure monitoring (C), cholesterol management (D), medication management (E), individual counselling (F), smoking secession (G), mental health (H). CR/SP, cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention.

Box 1. Topic list of WeChat-based cartoon-format health education.

Welcome to SMART-CR/SP from Dr Kang

Mr. Li’s heart attack (episode 1)

Mr. Li’s heart attack (episode 2)

How you heart works

Coronary heart disease

Angina and management

Heart attack signs

Action plan for heart attack

Risk factors of coronary heart disease

Clinical tests for coronary heart disease

Percutaneous coronary intervention therapy

Medication management after percutaneous intervention therapy

Physical activity after percutaneous intervention therapy (episode 1)

Physical activity after percutaneous intervention therapy (episode 2)

Physical activity after percutaneous intervention therapy (episode 3)

Healthy eating (episode 1)

Healthy eating (episode 2)

Healthy eating (episode 3)

Diet-fat facts

Diet-salt facts

Smoking cessation

Blood pressure management

Management of cholesterol

Management of diabetes

Weight management

Alcohol and heart health

Mental health and heart health

Back to normal life after percutaneous coronary intervention

Myths about coronary heart disease

Cardiac pulmonary resuscitation

Hands-only cardiac pulmonary resuscitation

Goodbye and long-term management

CR/SP, cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention

Role of the CR/SP coach

A cardiologist will act as the CR/SP coach, whose main task is to review participants’ data on a regular basis and provide guidance and medical advice as required. All questions and enquiries from participants will be reviewed and replied to by the CR/SP coach using the study’s official WeChat account (Dr Kang). Replies will be made within one business day, and video calls will be booked if required by the participants.

Exercise prescription and physical activity tracking

Participants will receive an individualised walking programme based on their baseline 6MWT, with both the time and intensity of walking increased gradually over the first 8 weeks. The target physical activity level will be 10 000 accumulated steps of walking per day, at least five times per week, in accordance with international recommendations.35 Utilising WeChat’s physical activity tracker, WeChat Sports, participants will be able to review their real-time, weekly and monthly step counts. The CR/SP coach, as a WeChat ‘friend’ of the participant, will have access to their step counts and will review participants’ physical activity data on a weekly basis, provide guidance and positive reinforcement on days that target physical activity levels are achieved. Participants will also be encouraged to undertake other forms of physical activity, such as swimming, Tai Chi, group dancing and table tennis.

Blood pressure monitoring and management

Participants will be provided with a Bluetooth enabled blood pressure monitoring device (C-health XY-10, Sky Innovation Technology Ltd (Shanghai)), and will be asked to measure their blood pressure on 2 days per week, with two measurements each day, 1 min apart. The blood pressure readings will be transmitted via Bluetooth technology to a dedicated application on participants’ smartphones where it will be uploaded to a data management portal which will be reviewed by the CR/SP coach and appropriate guidance will be provided to participants according to contemporary guidelines.36 A standard procedure and alerts will be employed when a participant’s measurement readings are outside the target levels. This will include WeChat alert messages send by the CR/SP coach to remind the participant to repeat their blood pressure measurement, adhere to medication and to seek medical advice from their healthcare givers if indicated. WeChat-based counselling will be provided if the participant prefers to receive advice directly from the CR/SP coach. This alert system will be ceased once the target blood pressure is achieved. To facilitate the ability of both the participants and the CR/SP coach to review the blood pressure data, blood pressure management applications will be installed on both participants’ and physician’s smartphones.

Cardiovascular risk factor monitoring and management

Cardiovascular risk factors for each participant will be assessed during the baseline face-to-face assessment. This will involve a detailed review of the participant’s PCI therapy, blood pressure, family history of cardiovascular disease (CVD), glucose levels, lipid profile, smoking status, body mass index, hip and waist circumferences, dietary habit, and whether the participant has existing sleep apnoea or diabetes. Data will be collected and managed using the REDCap electronic data capture tool hosted at Fudan University.37 After the initial assessment, participants will be informed of their target level for each risk factor by the CR/SP coach and encouraged to try and achieve this goal. Participants can update their CVD risk factor profile at any time through communication with the CR/SP coach on WeChat.

Healthy nutrition

To help participants understand and comply with dietary recommendations, cartoon-format educational articles developed according to contemporary guidelines38–40 will be sent to their WeChat account. Cultural considerations have been taken into account when developing the dietary content of the educational articles. In addition, participants will be able to photograph the food they consume and send the pictures to the CR-SP coach through WeChat to get feedback on the nutritional content of the food.

Cardiac medication management

The medication list of each participant will be reviewed by the CR/SP coach at baseline to ensure that the five classes of recommended cardioprotective medications have been prescribed (aspirin, ADP receptor antagonist, beta-blocker, angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) and a statin/lipid-lowering medication). If any of the cardioprotective medications are not prescribed for the participant then underlying reasons (contraindicated/previously documented intolerance) will be investigated. The participant will be notified and encouraged by the CR/SP coach to discuss their medication therapy with their doctors if they are not prescribed with these medications without justification. Additionally, information relating to the mechanism of these drugs, evidence of clinical benefits and common side effects will be described in detail in the WeChat cartoon-format educational articles to increase understanding and compliance rates.

Outcome assessment

The outcome measures for the trial are outlined in table 1. Baseline assessments will occur within 2 weeks of participants’ discharge from hospital, with follow-up at 8 weeks, 6 months and 12 months to evaluate both the short-term and longer term efficacy of the CR/SP intervention. The primary outcome will be the change in exercise capacity from baseline, as assessed by 6MWT distance at 8 weeks and 6 months, using a standardised protocol.41 In the 6MWT, oxygen saturation, blood pressure and heart rate of participants will be measured pretest and post-test.

Table 1.

Assessment time points for primary and secondary outcomes of SMART-CR/SP study

| Outcome | Assessment | Baseline | 8 week | 6 month | 12 month |

| Primary outcome | |||||

| Exercise capacity | Change in 6MWT distance | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Key secondary outcome | |||||

| Knowledge of the disease | Modified CHD questionnaire42 43 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| Blood pressure | Average of two resting, sitting digital recordings | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Lipid profile | Fasting blood sample | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Medication adherence | Adherent to cardiac-protective medications | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Smoking | Self-report | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Obesity | Weight, height, waist and hip circumference | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Physical activity | General Physical Activity Questionnaire46 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Fruit and vegetable intake | WHO Steps instrument44 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Anxiety symptoms | Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale47 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Depressive symptoms | Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)48 |

✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Quality of life | SF-12_V2 Health Survey49 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| CV events | CVD death, non-fatal AMI, stroke or hospital admission with unstable angina or congestive heart failure | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| CR/SP needs survey | Patient needs for the core components of CR/SP33 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| All-cause mortality | Data from CDC | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; BP, blood pressure; CDC, Centre Disease Control and Prevention; CHD, coronary heart disease; CR/SP, cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention; CV, cardiovascular; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; 6 MWT, 6 min walk test distance.

Secondary outcomes will be participant knowledge of CHD, evaluated by a CHD knowledge questionnaire based on two validated heart disease questionnaires,42 43 resting blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose and cholesterol levels, adherence to cardioprotective medications, behavioural CHD risk factors including unhealthy diet (WHO Steps instrument)44; smoking (Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence)45; low physical activity (IPAQ),46 overweight or obesity, as well as psychosocial factors including anxiety symptoms (Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale),47 depressive symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire),48 quality of life (SF-12 V2 Health Survey),49 major cardiovascular events (MACE) and all-cause mortality.

Health system and associated resource use relating to CHD will be collected during each follow-up visit from participants’ self-report and cross-checked against hospital records. This will include: emergency department presentations, hospital admissions, outpatient clinic attendances and community doctor and specialist consultations. The cost of resource use relating to CHD will be valued based on the current manual of resource items and their associated costs published by the Shanghai Municipal Health and Family Planning Commission.

Evaluation of participants’ perceptions of SMART CR/SP

Process evaluation will be undertaken by user surveys and focus group discussions. At the completion of the trial, participants from the intervention group will be invited to complete a WeChat-based questionnaire to evaluate their experience and perceptions of the programme. A subgroup of participants from the intervention group will be randomly selected and invited to participate in focus group discussions, to gain a more in-depth understanding of the end users’ acceptability of the programme, their experiences and expectations of future smartphone and social media-based CR/SP models. We anticipate approximately five focus groups will be required, however, sampling will be ceased once thematic saturation is reached. Focus groups will be conducted by an experienced researcher (Dr Gang Zhao), digitally recorded and transcribed. Data will be sorted, coded and assigned to categories based on the objectives via an inductive approach.

Statistical considerations and data management

The intention to treat principle will be adopted and participants’ outcomes will be analysed according to the group to which they are allocated. Baseline characteristics of the cohort will be summarised using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables will be reported as mean and SD and be compared using linear regression models. Potential confounders and baseline values of the dependent variables will be entered as covariates. Categorical variables will be described as frequencies and percentages and compared using χ2 test. Mann-Whitney U test will be used if data are not normally distributed. A Cox proportional hazard model will be performed to analyse hospital readmission, outpatient clinic and emergency department visits. The criterion for statistical significance will be set at p<0.05. The statistical analysis will be conducted using SPSS V.24.

Data will be de-identified once collected, and a study ID will be developed for each participant. Only authorised researchers will have access to the data. Furthermore, a variety of security controls will be implemented. Given the short period of the intervention and low risk of the trial, a data monitoring committee will not be formed. However, regular data review will be performed to minimise adverse events and other unintended effects.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) played a key role in this study. During the study design, intervention platform development and piloting, post PCI patients and their relatives were invited to take part in surveys and focus group discussions. This allowed us to develop a comprehensive understanding of their perceptions and needs in relation to CR/SP services, facilitators and barriers for participating in CR/SP, as well as the acceptability of mHealth-based CR/SP services. Furthermore, surveys among medical staff were conducted to understand their priorities, experience and preferences relating to CR/SP service development and provision. PPI also provided valuable information to help the research team to select the appropriate intervention delivery method, questionnaires and outcome measures, along with the burden of the intervention. The results of the study will be disseminated to PPI representatives and study participants who wished to be notified.

Ethics and dissemination

The Human Research Ethics Committee of Fudan University Zhongshan Hospital granted the primary ethics approval for the trial (HREC B2016-058). The Curtin University Human Research Ethics Office granted the reciprocal approval for the trial (HRE2016-0120). The report of the study will be disseminated via scientific forums including peer-reviewed publications and presentations at national and international conferences.

Discussion

The SMART-CR/SP study will evaluate the feasibility and impact of an innovative smartphone and WeChat-based home CR/SP programme for patients with CHD, after PCI therapy. We are not aware of any previously published studies that have reported the efficacy of a smartphone and social media CR/SP service delivery model.

Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention is a Class I recommendation for the management of patients with CHD.33 However, despite the growing evidence of its cost-effectiveness10 and efficacy in reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,7 CR/SP services are limited in China. A recent national survey showed that only 30 of 124 (24%) large medical centres surveyed in China have operational CR programmes, translating to approximately two programmes per 100 million inhabitants.15 To address this service provision gap, there is a clear need to develop alternative delivery models to increase access to CR/SP services. Social media offers great potential for delivering health education and support through smartphones. Compared with past telephone and text message support, smartphones and social media may provide a more powerful, multifunctional platform for disease management. This includes access to step counting, multimedia messaging, voice/video call and group discussion. In China and other LMICs, where access to tertiary and secondary prevention healthcare are often limited, these advanced technology functions may greatly facilitate the delivery of core components of modern CR/SP to many patients with CHD who would not otherwise have had access to these important services. The potential reach of a smartphone and social media-based CR/SP intervention is great as it could easily be expanded to reach many smartphone and social media users at a low cost. Furthermore, this innovative service model could overcome common barriers to patients participating CR/SP programme, such as inconvenience, geographical isolation and financial burden,20 21 26 given it is easy to access, flexible and low cost.

In conclusion, SMART-CR/SP will test the usage of a smartphone and WeChat-based intervention to deliver the core components of guideline advocated CR/SP. If the efficacy of this social media-based CR/SP intervention is validated, this will have significant potential to improve access to evidence-based CR/SP for patients with CHD. This is likely to translate to improved patient outcomes and reduced financial burden of CVD on health systems. Although the focus of this study is the delivery of a CR/SP intervention via smartphone and WeChat, there is great potential that this model of care could be adopted in both the primary and secondary prevention context for other chronic diseases, and using other social media platforms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the valuable contribution made by the patients and public representatives during the study design and intervention development.

Footnotes

Contributors: TD and AM: conceived the original concept of the study and wrote the first draft of the protocol manuscript. GZ, AS, LT, JW, YC, KT, B-KT, JG: contributed to the design of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work is funded by TD’s PhD scholarship from Curtin University. All blood pressure monitors were donated by Sky Innovation Technology (Shanghai) Limited. Significant ‘in-kind’ support (staff time) was provided by Fudan University Zhongshan Hospital.

Disclaimer: No staff from the company will be involved in the design, implementation and data analysis of the study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: For patient confidentiality concerns and the access possibilities of the data source, the clinical data collected will not be shared with the public. However, non-clinical data, such as WeChat educational materials, will be shared with the public and other researchers.

References

- 1. Weiwei C, Runlin G, Lisheng L, et al. Outline of the report on cardiovascular diseases in China 2016. China Journal of Circulation 2017;32:521–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bi Y, Jiang Y, He J, et al. Status of cardiovascular health in Chinese adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:1013–25. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moran A, Gu D, Zhao D, et al. Future cardiovascular disease in china: markov model and risk factor scenario projections from the coronary heart disease policy model-china. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010;3:243–52. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.910711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yusuf S. Two decades of progress in preventing vascular disease. Lancet 2002;360:2–3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09358-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clark AM, Hartling L, Vandermeer B, et al. Secondary prevention programmes for coronary heart disease: a meta-regression showing the merits of shorter, generalist, primary care-based interventions. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2007;14:538–46. 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328013f11a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frederix I, Hansen D, Coninx K, et al. Effect of comprehensive cardiac telerehabilitation on one-year cardiovascular rehospitalization rate, medical costs and quality of life: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016;23 10.1177/2047487315602257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Anderson L, Oldridge N, Thompson DR, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease: cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:1–12. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pack QR, Squires RW, Lopez-Jimenez F, et al. Participation rates, process monitoring, and quality improvement among cardiac rehabilitation programs in the united states: a national survey. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2015;35:173–80. 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Laukkanen JA. Cardiac rehabilitation: why is it an underused therapy? Eur Heart J 2015;36:1500–1. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jelinek MV, Thompson DR, Ski C, et al. 40 years of cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention in post-cardiac ischaemic patients. Are we still in the wilderness? Int J Cardiol 2015;179:153–9. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.10.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Berry JD. Preventive cardiology update: controversy, consensus, and future promise. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2015;58:1–2. 10.1016/j.pcad.2015.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chew DP, French J, Briffa TG, et al. Acute coronary syndrome care across Australia and New Zealand: the SNAPSHOT ACS study. Med J Aust 2013;199:185–91. 10.5694/mja12.11854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shanmugasegaram S, Perez-Terzic C, Jiang X, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation services in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2014;29:454–63. 10.1097/JCN.0b013e31829c1414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Turk-Adawi K, Sarrafzadegan N, Grace SL. Global availability of cardiac rehabilitation. Nat Rev Cardiol 2014;11:586–96. 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang Z, Pack Q, Squires RW, et al. Availability and characteristics of cardiac rehabilitation programmes in China. Heart Asia 2016;8:9–12. 10.1136/heartasia-2016-010758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang W, Chair SY, Thompson DR, et al. Health care professionals' perceptions of hospital-based cardiac rehabilitation in mainland China: an exploratory study. J Clin Nurs 2009;18:3401–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02876.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jin H, Wei Q, Chen L, et al. Obstacles and alternative options for cardiac rehabilitation in Nanjing, China: an exploratory study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2014;14:20 10.1186/1471-2261-14-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Varnfield M, Karunanithi M, Lee CK, et al. Smartphone-based home care model improved use of cardiac rehabilitation in postmyocardial infarction patients: results from a randomised controlled trial. Heart 2014;100:1770–9. 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Neubeck L, Redfern J, Fernandez R, et al. Telehealth interventions for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: a systematic review. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2009;16:281–9. 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32832a4e7a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rawstorn JC, Gant N, Direito A, et al. Telehealth exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart 2016;102:1183–92. 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Szalewska D, Zieliński P, Tomaszewski J, et al. Effects of outpatient followed by home-based telemonitored cardiac rehabilitation in patients with coronary artery disease. Kardiol Pol 2015;73:1101–7. 10.5603/KP.a2015.0095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhao J, Freeman B, Li M. Can mobile phone apps influence people’s health behavior change? An evidence review. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e287 10.2196/jmir.5692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. West JH, Belvedere LM, Andreasen R, et al. Controlling your "App"etite: how diet and nutrition-related mobile apps lead to behavior change. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5:e95 10.2196/mhealth.7410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pfaeffli Dale L, Whittaker R, Jiang Y, et al. Text message and internet support for coronary heart disease self-management: results from the text4heart randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e237 10.2196/jmir.4944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Interlligence P. WeChat 2017 user research and business opportunities insight. 2016. http://tech.qq.com/a/20170424/004233.htm#p=4

- 26. He C, Wu S, Zhao Y, et al. Social media-promoted weight loss among an occupational population: cohort study using a wechat mobile phone app-based campaign. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e357 10.2196/jmir.7861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRIT 2013: new guidance for content of clinical trial protocols. Lancet 2013;381:91–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62160-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2015;38:506–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Casillas JM, Hannequin A, Besson D, et al. Walking tests during the exercise training: specific use for the cardiac rehabilitation. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2013;56:561–75. 10.1016/j.rehab.2013.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gremeaux V, Troisgros O, Benaïm S, et al. Determining the minimal clinically important difference for the six-minute walk test and the 200-meter fast-walk test during cardiac rehabilitation program in coronary artery disease patients after acute coronary syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92:611–9. 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Beatty AL, Schiller NB, Whooley MA. Six-minute walk test as a prognostic tool in stable coronary heart disease: data from the heart and soul study. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1096–102. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Woodruffe S, Neubeck L, Clark RA, et al. Australian Cardiovascular Health and Rehabilitation Association (ACRA) core components of cardiovascular disease secondary prevention and cardiac rehabilitation 2014. Heart Lung Circ 2015;24:430–41. 10.1016/j.hlc.2014.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kaminsky LA, Brubaker PH, Guazzi M, et al. Assessing physical activity as a core component in cardiac rehabilitation: a position statement of the american association of cardiovascular and pulmonary rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2016;36:217–29. 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Organization WH. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry Geneva, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gabb GM, Mangoni AA, Anderson CS, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of hypertension in adults - 2016. Med J Aust 2016;205:85–9. 10.5694/mja16.00526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang SS, Lay S, Yu HN, et al. Dietary guidelines for chinese residents (2016): comments and comparisons. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 2016;17:649–56. 10.1631/jzus.B1600341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Smith SC, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation 2011;124:2458–73. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318235eb4d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J 2016;37:2315–81. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Singh SJ, Puhan MA, Andrianopoulos V, et al. An official systematic review of the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society: measurement properties of field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1447–78. 10.1183/09031936.00150414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chan CW, Lopez V, Chung JW. A survey of coronary heart disease knowledge in a sample of Hong Kong Chinese. Asia Pac J Public Health 2011;23:288–97. 10.1177/1010539509345869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wagner J, Lacey K, Chyun D, et al. Development of a questionnaire to measure heart disease risk knowledge in people with diabetes: the Heart Disease Fact Questionnaire. Patient Educ Couns 2005;58:82–7. 10.1016/j.pec.2004.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Edwards P, Williams-Roberts H, Sahely B, et al. The WHO STEPwise approach to chronic disease risk factor surveillance (STEPS). Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. The fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the fagerström tolerance questionnaire. Br J Addict 1991;86:1119–27. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. World Health Organisation. Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) analysis guide. 2011. http://www.who.int/chp/steps/resources/GPAQ_Analysis_Guide.pdf.

- 47. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.