Abstract

Poverty is an important patient-reported outcome of therapy and a potential predictor of outcome disparities in pediatric cancer. We previously identified that nearly 30% of pediatric cancer families experience household material hardship (HMH), a concrete measure of poverty including food, energy, or housing insecurity, during the first 6 months of chemotherapy. We conducted a follow-up survey in a subcohort of these families at least 1 year off-therapy and found that 32% reported HMH in early survivorship. Persistently high concrete resource needs off-therapy may have significance for child health and quality of life, and thus represent targets for future investigation.

Keywords: outcomes, pediatric oncology, postchemotherapy, poverty, quality of life, survivorship

1 | INTRODUCTION

Recent literature has identified social determinants of health—nonbiological correlates of health outcomes such as poverty, financial burden, or medication adherence—as targets for investigation in the early childhood cancer treatment setting.1–5 In 2016, the strong correlation between poverty and inferior pediatric health outcomes prompted the American Academy of Pediatrics to recommend universal pediatric poverty screening.6 Concurrently, the Children’s Oncology Group and American Psychosocial Oncology Society endorsed new standards acknowledging financial strain as an important patient-reported outcome and “strongly recommended” systematic screening from diagnosis into survivorship or bereavement.7,8

Household material hardship (HMH), including food, housing, or energy insecurity, is an appealing concrete measure of financial burden as it is associated with health outcomes in general pediatrics9 and can be ameliorated through systematic linkage with government or community resources.10,11 We previously described the frequency of HMH in a cohort of newly diagnosed pediatric cancer families and found that, in concert with national data, 20% were experiencing HMH at diagnosis.1,12,13 This increased to nearly 30% following 6 months of chemotherapy.1 We now sought to describe the frequency of HMH and financial burden in early survivorship and hypothesized that both patient-reported outcomes would be prevalent.

2 | METHODS

We utilized a subcohort of the previously published Oncology Economic Impact Study (Onc EIS) to conduct a cross-sectional “Long-Term Follow-up” (T3) survey of HMH at least 1 year off-therapy from October 31, 2014 through September 15, 2015.1 Onc EIS was a prospective two time-point survey investigation of HMH in 99 newly diagnosed pediatric cancer families treated at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center in Boston, Massachusetts from 2011 to 2013.1 Onc EIS participants completed a baseline survey within 30 days of diagnosis and a follow-up survey after 6 months of chemotherapy.

Participants in this follow-up study completed the additional T3 survey at least 1 year off-therapy. This study was approved by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board.

2.1 | Study population

Eligibility criteria for T3 included (1) Onc EIS participant who completed baseline and 6 month surveys and agreed to future contact, (2) child at least 1 year off-therapy, (3) child neither relapsed nor died, and (4) primary team permission to approach.

2.2 | Data collection

Of the N = 99 Onc EIS cohort, 68 (69%) families were eligible for T3. Eligible families were contacted by a research assistant and asked to complete a one-time survey either in-person or via telephone; questions were read aloud. The 77-item T3 survey included domains of (1) demographics, (2) HMH, (3) employment and income, and (4) financial impact.

2.3 | Operational definition of variables

In concert with prior publications, we defined a family as having HMH if they endorsed at least one unmet need including food, energy, or housing.1,9 Year-specific federal poverty levels (FPLs) were based on the Department of Health and Human Services Poverty Guidelines and calculated as follows: baseline family income was divided by the year-specific poverty guideline for household size and multiplied by 100 to achieve percentage of FPL.14

2.4 | Statistical methods

We summarized child, family, and financial characteristics using descriptive statistics including frequencies, proportions, medians, interquartile ranges (IQRs), and ranges. To compare baseline characteristics between T3 participants and those either ineligible for T3 or who declined actively or passively to participate, we used Fisher’s exact test and Wilcoxon rank sum test to test categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Two-sided P values <0.05 were considered significant. Analyses were conducted using SAS v. 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

3 | RESULTS

Of the 68 families eligible for T3, 15 were unreachable, 53 were successfully contacted, and 52 consented to participate (76% response rate). The T3 survey was administered at least 1 year from the completion of therapy, a median of 2.6 years (1.3–3.7) from diagnosis; 42 (81%) surveys were administered by phone and 10 (19%) in-person.

To assess potential biases between T3 participants (N = 52) and nonparticipants (including those ineligible to participate or who declined to participate) (N = 47), we compared baseline characteristics between the two groups. While demographics at time of diagnosis did not differ statistically between T3 participants and nonparticipants, we noted a trend toward higher socioeconomic status in T3 families. At diagnosis, fewer T3 families reported HMH (15% vs. 26%; Fisher’s exact test P = 0.22) and more T3 families reported at least a college degree (83% vs. 68%; P = 0.1). Child disease characteristics did not differ statistically between groups, nor were there notable trends.

4 | T3 PARENT AND HOUSEHOLD CHARACTERISTICS AT BASELINE

A majority of parents were white (81%) and college educated (83%) (Table 1). Nearly all (96%) were employed with a median household income of $101,012 (IQR $72,690–$182,500), above the $83,700 median household income for families in Massachusetts.15

TABLE 1.

Baseline child and family characteristics of long-term follow-up survey (T3) respondents (N = 52)

| Frequency (%) or Median (p25, p75) | |

|---|---|

| Parental demographics at baseline | |

|

| |

| Parent completing survey: mother | 32 (62) |

|

| |

| Parent age | 39.3 (33.7, 46.2) |

|

| |

| Education | |

| High school education or less | 9 (17) |

| Associate/bachelors | 24 (46) |

| Masters/doctorate | 19 (37) |

|

| |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic or Latino | 2 (4) |

|

| |

| Race: non-White | 10 (19) |

|

| |

| Household characteristics at baseline | |

|

| |

| English as primary language | 50 (96) |

|

| |

| Single parent household | 7 (14) |

|

| |

| Household size | 4 (4, 5) |

|

| |

| Distance of home from DFCI (miles) | |

| 0–50 | 40 (77) |

| 50+ | 12 (23) |

|

| |

| Household income at diagnosis (dollars) | 101,012 (72,690, 182,500) |

|

| |

| Any parent in household unemployed at diagnosis (excluding stay at home parents) | 2 (4) |

|

| |

| Child, disease, and care characteristics | |

|

| |

| Female | 32 (62) |

|

| |

| Age at diagnosis | 5.5 (3, 12) |

|

| |

| Cancer diagnosis | |

| Hematologic malignancy | 28 (54) |

| Solid tumor | 15 (29) |

| Brain tumor | 9 (17) |

|

| |

| Health insurance | |

| Private ± Masshealth/Medicaid | 43 (83) |

| Medicaid/MassHealth only | 9 (17) |

| Uninsured | 0 (0) |

p25, p75: 25th percentile, 75th percentile.

5 | HOUSEHOLD MATERIAL HARDSHIP

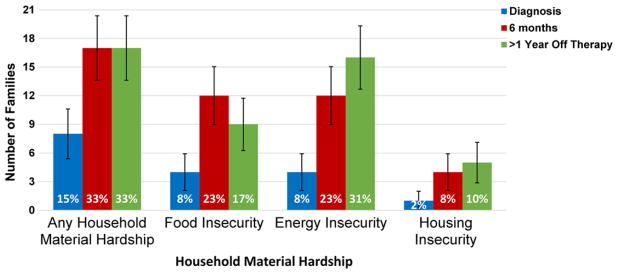

At diagnosis, 15% of families reported HMH. This increased to 33% after 6 months of chemotherapy, and persisted at 33% at T3 (Fig. 1). Family-reported food and energy insecurity, for which comparative national data exist, were significantly lower at baseline (8% each) than national averages (20% and 18%, respectively).12,13

FIGURE 1.

Material hardship within 30 days of diagnosis, after 6 months of chemotherapy, and at least 1 year off therapy (N = 52). *Error bars represent frequency ± 1 standard error

6 | IMPACT OF CHILD’S TREATMENT ON FAMILY FINANCES

Thirty-six percent of families (N = 18/50) reported losing >40% annual household income due to treatment-related work disruptions; median percent income lost was 22% (IQR 4.3–50). Forty-four percent of families endorsed experiencing “a great deal of financial hardship” due to their child’s illness and reported that they were “just getting by living paycheck to paycheck” all or most of the time. As a result of their child’s cancer and treatment, 40% (17/43) of families with a retirement fund at baseline stopped or reduced payments, and 50% (10/20) of families with a college fund at baseline stopped or reduced payments.

7 | DISCUSSION

We previously reported that 29% of pediatric oncology families at a large referral center experienced food, housing, or energy insecurity following 6 months of chemotherapy.1 We now describe HMH in the early off-therapy period. Strikingly, in this socioeconomically advantaged subcohort of our original investigation, the percentage of families reporting HMH doubled (15–33%) from baseline to off-therapy. Considering these data reflect the experience of a predominantly white, college-educated cohort with baseline incomes above the median at diagnosis, our findings highlight both the significant financial strain of pediatric cancer therapy and the vulnerability of “middle class” families unlikely to raise red-flags for resource needs at diagnosis. They further beg the question of what financial hardship lower income families are experiencing in early survivorship.

Our data represent a single center and a relatively small, socioeconomically advantaged cohort. This clear limitation may bias our findings toward underestimating the prevalence of HMH in a more socioeconomically diverse pediatric cohort. While administered at least 1 year off-therapy, the T3 survey was not given at a standardized time-point that limits our ability to describe time-specific outcomes. These data provide a first descriptive highlight of a seemingly significant problem in pediatric oncology.

Poverty—including HMH—is associated with inferior general pediatric health outcomes including metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular effects, delayed development, chronic illness, and injury.6,7,9,16–19 It is plausible that household poverty in the off-therapy setting may have implications for child health in survivorship—including adherence to recommended screening or risk of late effects. Over one in three children from middle class families appear to be living in homes with unmet basic resource needs during early cancer survivorship. Further investigation of the prevalence and impact of such need is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: St. Baldrick’s Foundation; Grant sponsor: National Palliative Care Research Center; Grant sponsor: ASCO; Grant sponsor: Pedals for Pediatrics; Grant sponsor: Family Reach Foundation; Grant sponsor: National Cancer Institute; Grant number: K07CA211847.

We would like to thank the DFCI families who participated in this study. We would also like to thank Dr. Deborah Frank who has been instrumental in the conception of this research. Dr. Bona is supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K07CA211847. The content in this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This longitudinal project was additionally supported by grants from the St. Baldrick’s Foundation, the National Palliative Care Research Center, ASCO, Pedals for Pediatrics and the Family Reach Foundation.

Abbreviations

- FPL

federal poverty level

- HMH

household material hardship

- IQR

interquartile range

- Onc EIS

Oncology Economic Impact Study

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bona K, London WB, Guo D, Frank DA, Wolfe J. Trajectory of material hardship and income poverty in families of children undergoing chemotherapy: a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(1):105–111. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatia S, Landier W, Hageman L, et al. 6MP adherence in a multiracial cohort of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Children’s Oncology Group study. Blood. 2014;124(15):2345–2353. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-552166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta S, Sutradhar R, Guttmann A, Sung L, Pole JD. Socioeconomic status and event free survival in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a population-based cohort study. Leuk Res. 2014;38(12):1407–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austin MT, Hamilton E, Zebda D, et al. Health disparities and impact on outcomes in children with primary central nervous system solid tumors. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2016;18(5):585–593. doi: 10.3171/2016.5.PEDS15704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lathan CS, Cronin A, Tucker-Seeley R, Zafar SY, Ayanian JZ, Schrag D. Association of financial strain with symptom burden and quality of life for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(15):1732–1740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.AAP Council on Community Pediatrics. Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20160339. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiener L, Kazak AE, Noll RB, Patenaude AF, Kupst MJ. Standards for the psychosocial care of children with cancer and their families: an introduction to the special issue. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(Suppl 5):S419–S424. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pelletier W, Bona K. Assessment of financial burden as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(Suppl 5):S619–S631. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frank DA, Casey PH, Black MM, et al. Cumulative hardship and wellness of low-income, young children: multisite surveillance study. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):e1115–e1123. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Silverstein M, Freeman E. Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: a cluster RCT. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):e296–e304. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berkowitz SA, Hulberg AC, Standish S, Reznor G, Atlas SJ. Addressing unmet basic resource needs as part of chronic cardiometabolic disease management. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):244–252. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez D, Aratani Y, Jiang Y. Energy insecurity among families with children. 2014 doi: 10.1080/10796126.2016.1148672. http://www.nccp.org/publications/pdf/text_1086.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Food Security Status of U.S. Households with children in 2015. United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2016. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/key-statistics-graphics.aspx#children. [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Prior HHS poverty guidelines and federal register references. 2017 http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/figures-fed-reg.shtml.

- 15.The Annie E. Casey Foundation, KIDS COUNT Data Center. [Accessed January 2017];Median family income among households with children. 2012 http://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/65-median-family-income-among-households-with-children#detailed/2/23/false/573,869,36,868,867/any/365.

- 16.Cook JT, Frank DA, Casey PH, et al. A brief indicator of household energy security: associations with food security, child health, and child development in US infants and toddlers. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4):e867–e875. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Connor GT, Quinton HB, Kneeland T, et al. Median household income and mortality rate in cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 2003;111(4 Pt 1):e333–e339. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.e333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung EK, Siegel BS, Garg A, et al. Screening for social determinants of health among children and families living in poverty: a guide for clinicians. Current Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2016;46(5):135–153. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holben DH, Taylor CA. Food insecurity and its association with central obesity and other markers of metabolic syndrome among persons aged 12 to 18 years in the United States. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2015;115(9):536–543. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2015.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]