Abstract

Background.

A definition of chronic pancreatitis (CP) is needed for diagnosis and distinguishing CP from other disorders. Previous definitions focused on morphology. Advances in epidemiology, genetics, molecular biology, modeling and other disciplines provide new insights into pathogenesis of CP, and allow CP to be better defined.

Methods.

Expert physician-scientists from the United States, India, Europe and Japan reviewed medical and scientific literature and clinical experiences. Competing views and approaches were debated until a new consensus definition was reached.

Results:

CP has been defined as ‘a continuing inflammatory disease of the pancreas, characterized by irreversible morphological change, and typically causing pain and/or permanent loss of function’. Focusing on abnormal morphology makes early diagnosis challenging and excludes inflammation without fibrosis, atrophy, endocrine and exocrine dysfunction, pain syndromes and metaplasia. A new mechanistic definition is proposed— ‘Chronic pancreatitis is a pathologic fibro-inflammatory syndrome of the pancreas in individuals with genetic, environmental and/or other risk factors who develop persistent pathologic responses to parenchymal injury or stress.’ In addition, “Common features of established and advanced CP include pancreatic atrophy, fibrosis, pain syndromes, duct distortion and strictures, calcifications, pancreatic exocrine dysfunction, pancreatic endocrine dysfunction and dysplasia.” This definition recognizes the complex nature of CP, separates risk factors from disease activity markers and disease endpoints, and allows for a rational approach to early diagnosis, classification and prognosis.

Conclusions:

Initial agreement on a mechanistic definition of CP has been reached. This definition should be debated in rebuttals and endorsements, among experts and pancreatic societies until international consensus is reached.

Introduction

In 1995 a “Medical Progress: Chronic Pancreatitis” feature in the New England Journal of Medicine correctly summarized the state of understanding of chronic pancreatitis (CP) with the following statement, “Chronic pancreatitis remains an enigmatic process of uncertain pathogenesis, unpredictable clinical course, and unclear treatment.”(1) Shortly thereafter, a series of scientific advances and clinical studies began revealing that CP is a group of complex disorders with overlapping features with no clear common denominator (2–8). Thus, CP cannot be considered a simple disorder with well-defined clinical features, a uniform etiology, and a stereotypic pathologic mechanism.

In 2013 DCW was invited to present a “consensus of consensus guidelines” on CP at the combined European Pancreatic Club (EPC) - International Association of Pancreatology (IAP) Meeting for June 24 −28, 2014, in Southampton, UK and to provide a manuscript of the proceedings. The presentation was to include an assessment of whether there is agreement, controversy or inadequate evidence on the important management points. After reviewing the literature and consulting with domain experts, it was concluded that there was no consensus on the definition of CP and the diagnostic criteria.

Historically, the framework for medicine in the 20th century emerged from the germ theory of disease where one, and only one factor could be the primary cause of a disease syndrome by fulfilling Koch’s postulates (9, 10). Application of this theory, with standardization of the “scientific method”, disease taxonomy, criteria for diagnosis, evidence based medicine and a curriculum for medical education defined Western medicine for a century and resulted in huge advances in simple infectious disease control and public health (11–13). However, like many other chronic disorders, CP is complex and no single factor is causative among patients. Therefore, it is not surprising that the traditional definition(s), diagnostic criteria and classification systems developed for CP using the germ theory paradigm fail to provide insights into etiology and meaningful clinical advances. The old framework is also proven to be inadequate when attempting to predict the natural history of the disease in individual patients or attempting to apply new molecular and genetic discoveries to the clinic. No consistently effective treatments for patients diagnosed with CP have been developed using the traditional approaches with the exception of supportive therapies or radical surgical procedures such as partial or total pancreatectomy, with or without islet autotransplantation.

Recent discoveries on complex gene-environment interactions in large subsets of patients with CP dictate that a germ theory-based model must be rejected and replaced by a new paradigm that provides insights into individual patients. The concepts of personalized, or precision medicines must be applied to CP (3, 9). A new approach must begin with a new mechanistic definition of CP that defines pathogenic processes in contrast to normal processes involving inflammation and fibrosis, and distinguishes CP from other diseases with overlapping features. It must also provide structure to assist in managing multiple types of information related to risk, disease activity and outcomes. Clear, robust definitions are also required, as disease models with predictive features are developed to provide useful guidance to physicians as they work to minimize human disease rather than treat the consequences of an enigmatic process.

Methods.

A systematic literature review of major consensus reports, invited expert reviews, systematic reviews, and landmark papers that were published between 1965 and 2014 on recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP) and CP was performed by DCW and JBG. Various consensus statements were organized and viewed from a historical perspective to understand the basis for recommendations or their attempt to revise previously published recommendations. Summary information was circulated among authors from India [PKG] Italy [LF]), Germany [AS], the United States of America [DY] and Japan [TS] to provide addition information, experiences, perspectives, comments and recommendations to address gaps in current knowledge and debate perspectives and approaches. The final draft is a consensus proposition.

Results.

The working group chose to present highlights from key historical conferences/consensus meetings focused on CP to provide the framework of the current clinicopathologic-based definition. Second, the limitations of a clinicopathologic definition are presented. Third, the rationale for the framework of a mechanistic definition of CP is provided. Fourth, a conceptual model of the process of CP, extending from risk to end-stage disease is outlined. In addition to the proposed definition statements, a series of discussion questions are listed for ongoing discussion (List 1).

Historic Definition of CP

The definition of CP serves as the foundation for early detection, diagnosis and distinction from other syndromes with overlapping features. While there are many proposed definitions, seven important perspectives developed by expert consensus groups are given for historical perspective and further discussion.

Marseille:

The initial efforts for a consensus definition of CP were conducted in Marseille and Rome in 1963, 1984 and 1988 (14–16) (reviewed in Etemad and Whitcomb (17)). Although the morphological, functional and clinical criteria were carefully described in the Marseille conferences, the primary distinction between acute and chronic pancreatitis was the resolution of symptoms in acute pancreatitis (AP) versus the permanent changes in histology, and often (but not always) associated with persistent clinical and functional impairment in CP.

Cambridge:

An independent group of experts met in Cambridge, England in March 1983 to improve on the Marseille classification, and proposed the Cambridge Classification of pancreatic severity (18). The Marseille classification was criticized because there were no acceptable criteria for ‘irreversible morphological change’ or ‘loss of function’, and because it was unclear as how to classify RAP (18). Further, it was recognized that there may be lasting morphological changes in the pancreatic parenchyma years after a single episode of AP, as recently confirmed with more advanced techniques (19). The workshop members therefore defined CP as “a continuing inflammatory disease of the pancreas, characterized by irreversible morphological change, and typically causing pain and/or permanent loss of function.” Other groups have adopted this, or similar definitions, including the recent Italian consensus guidelines (ICG)(20) and Spanish recommendations (SR)(21, 22).

Japan:

From 1991–1994 the Japanese Pancreas Society met to defined CP. They concluded that CP was “a chronic clinical disorder, pathologically characterized by the loss of exocrine and endocrine pancreatic parenchyma, irregular fibrosis, cellular infiltration, and ductal abnormalities” (23, 24). They also noted that, “in general, these lesions do not resolve and show various levels of deterioration.” They also recognized the progressive nature of CP, and recommended that treatment should start prior to the diagnosis of CP and during the early phases defined as “probable CP.”

Zürich:

A workshop of experts met in Zürich, Switzerland in 1996 to develop a clinically based classification system for alcoholic CP (Zürich Workshop) (25). CP was designated as a “classic disease without a clinically valid, generally recognized definition”. The focus was on alcoholic CP (ACP), which was divided into a “Probable ACP”, a pre-CP phase lasting about 5 years and defined by RAP and a history of excessive alcohol intake (e.g. >80 grams per day in men), and “Definite ACP “ the presence of CP features such as pancreatic calcifications, ductal changes and exocrine insufficiency. The recommendations were limited because the effects of smoking and genetic factors that alter the clinical severity of CP were not known.

United States:

The North American Pancreatitis Study Group (NAPSG) steering committee modified the Cambridge workshop definition of CP for the North American Pancreatitis Study II (NAPS2) in 1999. CP was defined as a “syndrome of destructive, inflammatory conditions that encompasses the many sequelae of long-standing pancreatic injury” (17). This definition was developed to be inclusive of all morphological, clinical and functional variants, with the intention of then classifying patients by etiologies and by the major features or outcomes (e.g. atrophy, fibrosis, episodic or continuous pain, quality of life, pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, cancer), since these complications are not surrogates of each other (e.g. the degree of fibrosis does not predict the degree of pain or presence of diabetes mellitus). It also allowed for the inclusion of RAP, which was distinguished from CP in the NAPS2 program by the absence of features of irreversible morphologic changes on abdominal imaging, and of “minimal change” pancreatitis, in which the irreversible features were more functional than morphologic. Thus, it captured the concepts of the Japan Pancreas Society and the Zurich Workshop of “probable” CP, but framed it as beginning with AP that progressed to RAP (Sentinel Acute Pancreatitis Event [SAPE] model (3)).

Germany:

A multi-national working group organized by the German Association of Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (German Clinical Practice Guidelines, GCPG (26)) defined CP in 2013 as “a disease of the pancreas in which recurrent episodes of inflammation lead to replacement of the pancreatic parenchyma with fibrotic connective tissue”. The advantage of this definition is its simplicity and the ability to make the diagnosis using abdominal imaging, but limits the consequences of pancreatic inflammation to fibrosis, thereby excluding atrophy and minimal change disease as being CP. The English version of the S3-Leitlinie Chronische Pankreatitis consensus guidelines (27) reported strong consensus on a more extensive definition, “Chronic pancreatitis is a disease of the pancreas in which recurrent inflammatory episodes result in replacement of pancreatic parenchyma by fibrous connective tissue. This fibrotic reorganisation of the pancreas leads to a progressive exocrine and endocrine pancreatic insufficiency. In addition, characteristic complications arise, such as pseudocysts, pancreatic duct obstructions, duodenal obstruction, vascular complications, obstruction of the bile ducts, malnutrition and pain syndrome. Pain presents as the main symptom of patients with chronic pancreatitis. Chronic pancreatitis is a risk factor for pancreatic carcinoma. Chronic pancreatitis significantly reduces the quality of life and the life expectancy of affected patients.” This remains a useful descriptive definition of a progressive disorder.

American Pancreatic Association Practice Guideline:

The APA guidelines, published in 2014 (5) largely followed the Cambridge definition in characterizing CP as a syndrome of chronic progressive pancreatic inflammation and scarring, irreversibly damaging the pancreas and resulting in loss of exocrine and endocrine function. The pathologic section went on to characterize CP by atrophy and fibrosis of the exocrine tissue with or without chronic inflammation.

Limitations to the historic approach to defining CP by pathologic criteria alone:

The working group remains impressed with the thoughtfulness of the previous consensus groups in defining CP using the information and concepts at the time of their development. In general, most groups appeared to take a pragmatic approach beginning with end-stage disease and working backwards to early signs and symptoms. In many cases, key foundational information on the role of genetics and complex gene-environmental interactions was unknown or genetic information was handled as rare Mendelian disorders.

Fibrosis as a surrogate for CP pathology:

A limitation of the CP definitions since the Cambridge definition in 1983 is the sizable reliance on structural changes related to fibrosis. Conceptually, this approach could be justified if structural, functional and clinical signs and symptoms were tightly linked, and could be used as surrogates of each other. However, this assumption fails clinical testing, as fibrosis dose not correlate with pain (28, 29) and morphologic images or histology do not correlate highly with pancreatic function test results (5, 30–33). Furthermore, issues of proximal causality, rather than the inflammatory response leading to fibrosis, are not adequately addressed. This issue also becomes important for addressing the problem of reverse causality where distinctions should be made between long-standing diabetes mellitus (DM) causing atrophy and/or fibrosis and CP causing DM, or pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) causing pancreatic fibrosis rather than CP predisposing to PDAC (34).

The Role of Etiology:

With the exception of heavy alcohol use and rare Mendelian disorders, the issue of etiology and mechanism of disease are generally lacking. The exception is the APA Practice Guidelines that recommend using the TIGAR-O classification system of risk (35) for further classification (5), although this recommendation was not further developed.

CP defined as an outcome:

Each of the earlier consensus groups defined CP by pathologic criteria, although the Japanese Pancreas Society, Zürich Workshop, the NAPS2 steering committee and APA Practice Guidelines participants recognize the importance of early pathogenic processes that could not be defined or diagnosed using existing (morphologic) methods. Physicians recognize that something abnormal develops that eventually leads to morphologic changes that meet their diagnostic criteria for CP, and that this process continues to drive fibrosis and other complications of pancreatic inflammation to end stage disease. In this regard, it is important to decide whether the term “chronic pancreatitis” should be used to define a pathogenic process, a pathologic state, or an irreversible pathologic outcome resulting from chronic inflammation. While all three approaches are similar in end-stage disease, early diagnosis become challenging and arbitrary when the amount of fibrosis to qualify as definite CP is established (especially considering autopsy studies), or when abnormal function is detected, since most biological systems have significant adaptive processes and physiologic reserve that must be exhausted before significant dysfunction (e.g. statistically outside normal variation) is detected. A mechanistic definition is attractive because it focuses on the pathogenic process that can be predicted prior to the onset of pathology, can be monitored in multiple ways, and can be targeted with therapeutic and preventative approaches. However, such a definition does not yet exist.

Toward developing a mechanistic definition of CP:

A mechanistic definition should begin with an understanding of normal development, physiology, and response to common types of stresses or injury with an inflammatory response followed by reprograming and regeneration of cells with a return, over an interval of time, to a normal state. Thus, both conceptual and functional models of pancreatic biology are needed, with appropriate attention to the component parts. The mechanistic definition should be holistic, recognizing that multiple parts are interconnected and contribute in various ways to the whole. The mechanistic definition must also link clinical terms and disease mechanisms, since specific mechanisms determine the prognostic and therapeutic directions. Multiple pathological pathways and outcomes characterize CP, and all appropriate features and combinations should be considered. In some cases, clinical experience determines important aspects of pancreatic disease that are not intuitive from the study of simple models, and both heuristic and reverse engineering approaches may be needed to understand the underlying mechanisms so that the condition can be classified, modeled, detected early and managed.

The idea of “Probable CP” and “Definite CP” advanced by the Japan Pancreas Society, the Zurich Workshop and others represents mechanistic ideas of disease progression and these clinical ideas should be captured and explained in a mechanistic definition of CP or within diagnostic approaches. The definition needs to be broad enough to encompass all forms of pancreatic inflammation and its consequences, yet be distinct from AP, DM and PDAC. Whether there is utility in defining the type of inflammatory cells, cytokines or biomarkers within the pancreas at defined time points to distinguish CP from AP, DM and/or PDAC should also be considered in subsequent diagnostic and management discussions. This approach has been applied to autoimmune pancreatitis Type 1 and Type 2 (36, 37) as a method to better define this type of pancreatitis from other pancreatic conditions, with implications for aggressive treatment.

Within the broad mechanistic definition of CP, the implications for diagnosis and disease classification must be considered. Examples include cystic fibrosis, hereditary pancreatitis, autoimmune pancreatitis, Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, metaplastic conditions, atrophy and others. Attention must be given to differentiate the cause of injury and stress, the character and magnitude of the response, factors that modify the response, and the regeneration process. Clear descriptions and methods of classifying pathogenic gene-environment interactions must be developed.

The term “pancreatitis” should be used to describe inflammation and should not be confused with “pancreatic fibrosis”, “pancreatic exocrine insufficiency”, “pancreatogenic diabetes mellitus”, or “pancreatic pain.” “Alcoholic Pancreatitis” is a clinical term but does not adequately describe the etiology or underlying mechanisms and can be associated with various pancreatic parenchymal changes that may or may not be true CP-associated changes. “Minimal change CP” (MCCP) should refer specifically to minimal morphologic changes in the presence of inflammation-associated pancreatic disease and be diagnosed within a mechanistic CP disease model.

Conceptual model:

Three fundamental concepts guided the construction of a working model to guide development of a mechanistic definition of CP: the condition is acquired; the condition involves inflammation; and resulting state(s) is/are abnormal.

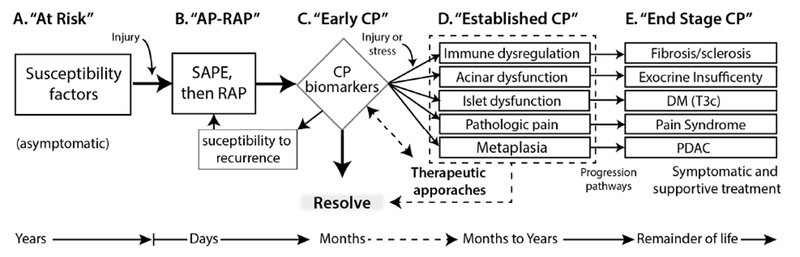

A conceptual model of CP was derived from the SAPE model (3), recognizing that subjects may exist in an A) “at-risk” state of CP, or in four active states; B) AP response; C) Early CP; D) Established CP; and E) End-stage CP (Figure 1). The transition from A to B involves activation of the immune system such as with a sentinel acute pancreatitis event (SAPE). This may or may not be clinically recognized. The course of AP can vary with evidence of an abnormal response in terms of magnitude, duration, type, and/or resolution/regeneration. State “C” is labeled “early CP”, but may overlap conceptually with “minimal change CP” or “pre-CP”, depending on eventual diagnostic criteria and distinctions from other states. The transition from B to C involves detection of biomarkers of CP pathogenesis or pathology, but does not reach a state of established CP. Biomarkers may be biochemical, structural or functional and may reflect abnormalities of acinar cells, duct cells, islet cells (as a secondary complication), nerves, stellate cells, immune cells or blood vessels. The transition from “C” to “D” involves progression of disease to a persistent state of pathology or dysfunction that crosses diagnostic thresholds of severity. States C and D should include measures of disease activity assessed over time so that disease trajectories (e.g. resolving, stable or progressive) can be charted to better assess prognosis and/or response to treatment. Progression from “D” to “E” reflects irreversible changes characteristic of end-stage disease that may include pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI), pancreatogenic diabetes mellitus (DM Type 3c), or neoplasia (e.g. pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, PDAC). Importantly, the various pathogenic processes are not surrogates of each other, and each problem and progressive state may need to be monitored independently.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model of CP used for definition development. The model helps in organizing the genetic and environmental risk factors, the role of recurrent injury or stress, and the normal and abnormal response to the injury→inflammation→ resolution → regeneration sequence (see text). Stage C includes the detection of features of later stages (D & E) but they are not persistent or have not progressed to the stage of established CP. Preventative and Therapeutic approaches are aimed at Stages C and D (dashed lines), whereas symptomatic and function replacement therapies (e.g. pancreatic enzyme replacement, insulin replacement) are the mainstay of Stage E. The features in D and E are not surrogates of each other and may need to be monitored independently. AP-RAP, acute pancreatitis and recurrent acute pancreatitis; CP, chronic pancreatitis; DM (T3c), diabetes mellitus Type IIIc or pancreatogenic diabetes mellitus; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; SAPE sentinel acute pancreatitis event.

Discussion.

A useful definition is a statement of the meaning of a term that both describes a concept and delineates the inclusion / exclusion boundaries. We believe that traditional definitions of CP tend to be extensional (listing the features) rather than intensional (describing the essence of the concept), which is problematic when the features are nonspecific and the goal is early detection linked to and targeted at, preventative treatments. A mechanistic definition overcomes these limitations by focusing on the essence and potential consequences of the disorder, and is applicable to both individual persons and groups of people. Indeed, knowledge of the mechanisms is fundamental to selecting strategies to prevent the development of downstream effects; recognizing that the benefits of identifying individual mechanisms and targeting treatments will depend on the stage of disease and disease activity levels in individual patients.

Initially the authors sought consensus on a definition of CP, diagnosis of CP and classification systems for CP that would allow early diagnosis and accurate prognosis. However, there were profound differences of opinions and approaches to CP, including diagnostic methods and criteria, inclusion/exclusion criteria, requirements for early diagnosis and classification systems. Specific areas of disagreement focused more on inclusion/exclusion criteria for entities such as autoimmune pancreatitis and whether or not fibrosis was required for CP or whether chronic inflammation with other complications should be considered CP. For example, in the definition of CP the use of the term “fibro-inflammatory syndrome” was preferred by the majority of authors, rather than an alternate term “inflammation-associated syndrome,” which does not imply that fibrosis as an essential feature and frames fibrosis as a common consequence of pathogenic conditions that may lead to pathologic fibrosis characteristic of established and end-stage “disease states,” was preferred by a minority of authors. After more than a year of debate it was decided to focus on the definition, postponing discussion of diagnosis and classification to later debate. An agreement was finally reached on a consensus working definition of CP, which would then serve as a basis for approaching diagnostic methods, and criteria and various classification systems in the future. The working group agreed that the definition should be presented to the broader pancreatic disease community as a Propositional Definition to be criticized or endorsed by experts, or by consensus statements by ad hoc groups or formal societies, associations or organizations. Thus, the working group believes that a progressive sequence is needed to accomplish a paradigm shift toward a more mechanistic understanding of CP. The process should begin with a definition (addressed here), then diagnostic criteria, and then classification system(s) with additional criteria. The current report focuses on the definition of CP.

Components of the definition.

The new definition begins with the concept that CP is an inflammation-associated disorder. The term “pancreatitis” itself means inflammation of the pancreas. The term “fibro-inflammatory” is intended for further defining the type of inflammation, although persistent inflammation with pathogenic features of CP but without “significant” fibrosis may be possible in some cases. The term “chronic” implies a persistent pathologic process, and is used to distinguish CP from AP.

A “syndrome” is a group of signs and symptoms that occur together to define a condition. The modifying word “pathologic” is intended to distinguish the normal signs and symptoms of pancreatic injury and recovery from injury, stress or acute inflammation from abnormal effects of inflammation resulting in persistent or progressive signs, symptoms or dysfunction. The definition intentionally does not include specifics on which signs and symptoms define CP, since these distinctions are within the domain of “diagnosis.”

The qualifying phrase “in individuals with genetic, environmental and/or other risk factors” recognizes the fact that there are mechanistic reasons for abnormal, pathologic responses. The phrase also acknowledges that great heterogeneity exists among patients with CP, and that different risk factors may be linked with abnormal responses in different relevant cell types at different times and under different conditions. Recognition of various risk factors also become important when signs of disease activity develop as they point to likely etiologies and targets for therapies.

The phrase “who develop persistent pathogenic responses to parenchymal injury or stress” distinguishes individuals who have a “normal” process of injury→ inflammation→ resolution→ regeneration from those who are predicted to have an “abnormal” response leading to clinically relevant symptoms and/or dysfunction. Key components of this phrase include the word “persistent,” which indicates chronicity but not necessarily permanent or irreversible, the word “response,” which distinguishes disease process from disease activity, and the word “pathogenic” which implies disease trajectory over a period of time. The term pathogenic may also alert the physician that interventions should be considered early to prevent end-stage disease.

Early Diagnosis of CP using the mechanistic definition of CP:

Under the Germ Theory paradigm the definition of CP relied on irreversible damage to the pancreas based on pathognomonic tissue histology, or fibrosis with morphologic changes as a surrogate of pathologic histology (35). However, since there is no “germ” or “toxin” to distinguish normal from abnormal, specific criteria based on the appearance of the tissue must be used to make the diagnosis. However, some degree of inflammation and fibrosis are components of normal pancreatic histology, with “normal” features changing with age and/or other conditions. Evidence of this limitation includes the high prevalence of “CP” in some autopsy studies of normal people, heavy alcohol users and subjects with renal disease (38, 39), and the poor consensus on the features of CP in high-resolution EUS studies (40–42). Stated another way, pancreatic fibrosis is a biomarker of an otherwise unspecified disorder that it is neither sensitive nor specific for the early diagnosis of CP. Since, in CP, the histologic diagnostic criteria are arbitrary and without consensus, and since there is a high prevalence of histologic features of CP in multiple populations without any other evidence of CP, a histologic (or surrogate histologic) diagnosis of early CP must be abandoned.

Both the Japanese Pancreas Society and Zürich workshop members recognized that there was often functional evidence of CP prior to the clear anatomic evidence required to make a histologic diagnosis. The concept of a state of “probable” CP was advanced, including the idea of early intervention, in spite of the fact that the condition could not be diagnosed. Functional features of CP include acinar cell dysfunction leading to PEI, duct dysfunction leading to low pancreatic juice bicarbonate levels, islet dysfunction leading to T3cDM, and pain. The challenges of using functional criteria include physiologic reserve and compensatory mechanisms, with PEI and DM being late features and pain being nonspecific and challenging to measure. Attempts to use pancreatic duct function as an early diagnostic tool for CP also faces challenges since multiple CFTR gene mutations result in defective bicarbonate conductance that is independent of inflammation or other pancreatic disease (43). The limitation of function testing was shown by Ketwaroo et al (32), who calculated that the positive predictive value of secretin-stimulated pancreatic function testing for early CP was only 45% while the negative predictive value was of 97%. Thus, the use of function testing to diagnose early CP defined by pathologic criteria is ineffective.

The expected advantage of the proposed Mechanistic Definition of CP is that, in a growing number of cases, early diagnosis will be possible based on a combination of risk factors and selected biomarkers of disease activity and/or progression. The identification of genetic risk factors provides mechanistic information on specific dysfunctional pathways, defines a population of people with high pretest probability that early signs and symptoms are likely due to early CP pathology. This provides utility for otherwise poorly functioning biomarkers since their use would be in a very high-risk population. In addition, negative genetic and/or other pre-existing risks lowers the likelihood that an abnormal clinical feature, such as pain, represents an abnormal response to pancreatic injury, and that other etiologies should be considered as being more likely.

In summary, a more mechanistic definition of CP is needed for the early diagnosis of pathologic processes that may eventually result in the pathologies characteristics of the end-stage CP syndrome. A new mechanistic definition is proposed that is intended to provide clarity in distinguishing CP from other disorders, while recognizing disease heterogeneity in terms of susceptibility, onset, modifying factors, rate of progression and outcomes. It also provides a pathway for defining overlapping syndromes such as autoimmune diseases, diabetes mellitus, pancreatic cancer, duct obstruction, atrophy, chronic pain, maldigestion and others. In conclusion, initial agreement on a mechanistic definition of CP has been reached. This definition should be debated among experts and specialty societies until an international consensus is reached.

Propositional mechanistic definition of CP.

“Chronic pancreatitis is a pathologic fibro-inflammatory syndrome of the pancreas in individuals with genetic, environmental and/or other risk factors who develop persistent pathologic responses to parenchymal injury or stress.”

In addition, the following features of the CP syndrome may or may not be present in individual cases:

“Common features of established and advanced CP include pancreatic atrophy, fibrosis, pain syndromes, duct distortion and strictures, calcifications, pancreatic exocrine dysfunction, pancreatic endocrine dysfunction, and dysplasia.”

These propositional statements are structured to serve as a foundation for future work on reaching a consensus to a mechanistic definition, diagnostic criteria, and disease classification in terms of subtypes, severity and prognosis.

Discussion questions.

Is pathologic fibrosis an absolute requirement for the definition of CP, or is it an eventual feature in most cases?

Does the term “fibro-inflammatory” in the proposed mechanistic definition of CP demand the inclusion of pathologic fibrosis to diagnose the syndrome, or should this be considered a more general concept where persistent inflammation in some patients may lead to atrophy, acinar cell dysfunction, Type 3c DM, pancreatic pain syndromes and/or metaplasia

If fibrosis is required, what are the criteria separating normal from abnormal (pathologic) fibrosis in terms of type, extent, histologic location, density and other necessary components?

If fibrosis is required for CP, are “minimal change CP” and “probable CP” excluded from the CP syndrome? (or do these cases remain in state “C”?)

If persistent inflammation is a criterion for CP, then is autoimmune pancreatitis a form of CP, or should it be considered an overlap syndrome when it results in fibrosis, atrophy, diabetes or other pathologic features resembling CP?

Is “pancreatopathay” a legitimate syndrome that is distinct from CP?

If pancreatopathy is a unique syndrome, how should it be defined in terms of pathologic concepts, inclusion/exclusion criteria and essential/common features, in what ways is it distinct from CP, and why is the distinction important?

Are Type 1 DM and/or Type 2 DM risk factors for CP, or is the atrophy, inflammation and/or fibrosis that is variably seen in these forms of diabetes a distinct or overlapping syndrome?

List 1. Major points of discussion that were considered important in framing a mechanistic definition of CP are listed as questions for ongoing debate. Answers to these questions also have implications in terms of future diagnostic criteria and classification systems.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank David Fine MD and Mark D. Topazian MD for critical review of the manuscript. DCW was supported by R21DK098560. DY and DCW were supported by DK077906 and 1U01DK108306.

Footnotes

There was no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Steer ML, Waxman I, Freedman S. Chronic pancreatitis. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;332(22):1482–90. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen JM, Ferec C. Genetics and pathogenesis of chronic pancreatitis: The 2012 update. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36(4):36(4):334–40. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitcomb DC. Genetic risk factors for pancreatic disorders. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(6):1292–302. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yadav D, Lowenfels AB. The epidemiology of pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(6):1252–61. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conwell DL, Lee LS, Yadav D, Longnecker DS, Miller FH, Mortele KJ, et al. American Pancreatic Association practice guidelines in chronic pancreatitis: evidence-based report on diagnostic guidelines. Pancreas. 2014;43(8):1143–62. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupte AR, Forsmark CE. Chronic pancreatitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2014;30(5):500–5. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosendahl J, Landt O, Bernadova J, Kovacs P, Teich N, Bodeker H, et al. CFTR, SPINK1, CTRC and PRSS1 variants in chronic pancreatitis: is the role of mutated CFTR overestimated? Gut. 2013;62(4):582–92. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witt H, Apte MV, Keim V, Wilson JS. Chronic pancreatitis: challenges and advances in pathogenesis, genetics, diagnosis, and therapy. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(4):1557–73. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitcomb DC. What is personalized medicine and what should it replace? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9(7):418–24. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falkow S Molecular Koch’s postulates applied to bacterial pathogenicity--a personal recollection 15 years later. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2(1):67–72. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flexner A Medical Education in the United States and Candida: A report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of teaching. Boston, Mass: 1910. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck AH. STUDENTJAMA. The Flexner report and the standardization of American medical education. JAMA. 2004;291(17):2139–40. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maeshiro R, Johnson I, Koo D, Parboosingh J, Carney JK, Gesundheit N, et al. Medical education for a healthier population: reflections on the Flexner Report from a public health perspective. Acad Med. 2010;85(2):211–9. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarles H Proposal adopted unanimously by the participants of the Symposium, Marseilles 1963. Bibliotheca Gastroenterologica. 1965;7:7–8. PMID: [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarles H, Adler G, Dani R, Frey C, Gullo L, Harada H, et al. The pancreatitis classification of Marseilles, Rome 1988. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24:641–. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singer MV, Gyr K, Sarles H. Revised classification of pancreatitis. Report of the Second International Symposium on the Classification of Pancreatitis in Marseille, France, March 28–30, 1984. Gastroenterology. 1985;89(3):683–5. PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lathrop G, Lalouel J, Juliet C, Ott J. Strategies for multilocus linkage analysis in human. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1984;81:3443–6. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarner M, Cotton PB. Classification of pancreatitis. Gut. 1984;25(7):756–9. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nikkola J, Rinta-Kiikka I, Raty S, Laukkarinen J, Lappalainen-Lehto R, Jarvinen S, et al. Pancreatic morphological changes in long-term follow-up after initial episode of acute alcoholic pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(1):164–70; discussion 70–1. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frulloni L, Falconi M, Gabbrielli A, Gaia E, Graziani R, Pezzilli R, et al. Italian consensus guidelines for chronic pancreatitis. Digestive & Liver Disease. 2010;42 Suppl 6:S381–406. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de-Madaria E, Abad-Gonzalez A, Aparicio JR, Aparisi L, Boadas J, Boix E, et al. The Spanish Pancreatic Club’s recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic pancreatitis: part 2 (treatment). Pancreatology : official journal of the International Association of Pancreatology. 2013;13(1):18–28. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez J, Abad-Gonzalez A, Aparicio JR, Aparisi L, Boadas J, Boix E, et al. The Spanish Pancreatic Club recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic pancreatitis: part 1 (diagnosis). Pancreatology. 2013;13(1):8–17. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Japan_Pancreas_Society. The Criteria Committee for Chronic Pancreatitis of the Japan Pancreas Society. Final report of clinical diagnostic criteria of chronic pancreatitis (in Japanese). J Jpn Panrrrus Soc 1995;10(4):xxiii–xxvi. PMID: [Google Scholar]

- 24.Homma T, Harada H, Koizumi M. Diagnostic criteria for chronic pancreatitis by the Japan Pancreas Society. Pancreas. 1997;15:14–5. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ammann RW. A clinically based classification system for alcoholic chronic pancreatitis: summary of an international workshop on chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1997;14(3):215–21. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayerle J, Hoffmeister A, Werner J, Witt H, Lerch MM, Mossner J. Chronic pancreatitis-definition, etiology, investigation and treatment. Deutsches Arzteblatt International. 2013;110(22):387–93. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffmeister A, Mayerle J, Beglinger C, Buchler MW, Bufler P, Dathe K, et al. [S3-Consensus guidelines on definition, etiology, diagnosis and medical, endoscopic and surgical management of chronic pancreatitis German Society of Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS)]. Zeitschrift fur Gastroenterologie. 2012;50(11):1176–224 [English Version: 10.055/s-0041-107379 Z Gastroenterol 2015; 53: 1447–1495] PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chowdhury R, Bhutani MS, Mishra G, Toskes PP, Forsmark CE. Comparative analysis of direct pancreatic function testing versus morphological assessment by endoscopic ultrasonography for the evaluation of chronic unexplained abdominal pain of presumed pancreatic origin. Pancreas. 2005;31(1):63–8. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilcox CM, Yadav D, Tian Y, Gardner TB, Gelrud A, Sandhu BS, et al. Chronic Pancreatitis Pain Pattern and Severity are Independent of Abdominal Imaging Findings. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;13(3):552–60. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heij HA, Obertop H, van Blankenstein M, ten Kate FW, Westbroek DL. Relationship between functional and histological changes in chronic pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31(10):1009–13. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alkaade S, Balci N, Momtahen A, Burton F. Normal pancreatic exocrine function does not excldue MRI/MRCP chronic pancreatitis findings. . J Clin Gastroenterol 2008;42:950–5. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ketwaroo G, Brown A, Young B, Kheraj R, Sawhney M, Mortele KJ, et al. Defining the accuracy of secretin pancreatic function testing in patients with suspected early chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(8):1360–6. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parsi MA, Conwell DL, Zuccaro G, Stevens T, Lopez R, Dumot JA, et al. Findings on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and pancreatic function test in suspected chronic pancreatitis and negative cross-sectional imaging. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(12):1432–6. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andersen DK, Andren-Sandberg A, Duell EJ, Goggins M, Korc M, Petersen GM, et al. Pancreatitis-diabetes-pancreatic cancer: summary of an NIDDK-NCI workshop. Pancreas. 2013;42(8):1227–37. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Etemad B, Whitcomb DC. Chronic pancreatitis: diagnosis, classification, and new genetic developments. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(3):682–707. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimosegawa T, Chari ST, Frulloni L, Kamisawa T, Kawa S, Mino-Kenudson M, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis: guidelines of the International Association of Pancreatology. Pancreas. 2011;40(3):352–8. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang L, Notohara K, Levy MJ, Chari ST, Smyrk TC. IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration in the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis. Mod Pathol. 2007;20(1):23–8. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Avram MM. High prevalence of pancreatic disease in chronic renal failure. Nephron. 1977;18(1):68–71. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pace A, de Weerth A, Berna M, Hillbricht K, Tsokos M, Blaker M, et al. Pancreas and liver injury are associated in individuals with increased alcohol consumption. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(11):1241–6. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petrone MC, Arcidiacono PG, Perri F, Carrara S, Boemo C, Testoni PA. Chronic pancreatitis-like changes detected by endoscopic ultrasound in subjects without signs of pancreatic disease: do these indicate age-related changes, effects of xenobiotics, or early chronic pancreatitis? Pancreatology. 2010;10(5):597–602. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stevens T, Lopez R, Adler DG, Al-Haddad MA, Conway J, Dewitt JM, et al. Multicenter comparison of the interobserver agreement of standard EUS scoring and Rosemont classification scoring for diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71(3):519–26. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kalmin B, Hoffman B, Hawes R, Romagnuolo J. Conventional versus Rosemont endoscopic ultrasound criteria for chronic pancreatitis: comparing interobserver reliability and intertest agreement. Canadian journal of gastroenterology = Journal canadien de gastroenterologie. 2011;25(5):261–4. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LaRusch J, Jung J, General IJ, Lewis MD, Park HW, Brand RE, et al. Mechanisms of CFTR functional variants that impair regulated bicarbonate permeation and increase risk for pancreatitis but not for cystic fibrosis. PLoS Genetics. 2014;10(7):e1004376 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]