Abstract

Introduction Unlike low-pressure hydrocephalus, very low pressure hydrocephalus (VLPH) is a rarely reported clinical entity previously described to be associated with poor outcomes and to be possibly refractory to treatment with continued cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage at subatmospheric pressures. 1, 2 We present four cases of VLPH following resection of suprasellar lesions and hypothesize that untreatable patients can be identified early, thereby avoiding futile prolonged external ventricular drainage in ICU.

Methods We performed a retrospective chart review of four cases of VLPH encountered between 2007 and 2015 in two different institutions and practices and tried to identify factors contributing to successful treatment. We hypothesized that normalization of frontal horn ratio (FHR), optimization of volume of CSF drained, and avoidance of fluid shifts would contribute to improved Glasgow Coma Score (GCS). We examined fluid shifts by studying net fluids shifts and serum levels of sodium, urea, and creatinine. We used Pearson and Spearman correlations to identify measures that would correlate with improved GCS.

Results Our study reveals that improving GCS is positively correlated with decreased FHR and increased CSF drainage within an optimal range. The most important determinant of good outcome is retention of brain viscoelasticity as evidenced by restoration and maintenance of good GCS score despite fluctuations in FHR.

Conclusion Futile prolonged subatmospheric drainage can be avoided by declining to continue treatment in patients who have permanently altered brain compliance secondary to unsealed CSF leaks, irremediable ventriculitis, and who are therefore unable to sustain an improved neurologic examination.

Keywords: very low pressure hydrocephalus (VLPH), CSF leak, frontal horn ratio, anterior skull base surgery, transsphenoidal surgery, suprasellar lesions

Introduction

Low-pressure hydrocephalus (LPH), 1 or syndrome of inappropriately SILPAH, 2 has been well described. It is comprised of symptoms of fatigue and difficulty walking, signs of apathy, mental slowness, or even decreased level of consciousness and leg weakness in the presence of enlarged ventricles but in the absence of symptoms of acute high intracranial pressure such as headache, nausea, and vomiting. LPH is unresponsive to shunting at positive pressures and only responds to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage at negative pressures as described in detail in past publications. The underlying problem is one of brain stiffening, or loss of elasticity, and change in viscoelastic modulus. 1 Adjuvant treatments include use of neck wrapping, or abdominal binders to produce venous engorgement and raise pressure in the cortical subarachnoid space (CSAS). 3 This allows for increased transmantle pressure gradients resulting in brain parenchymal expansion and decreased ventricular size thereby increasing CSF drainage from the ventricles. LPH has primarily been reported in the pediatric population; however, recent publications about adults have been seen in cases of subarachnoid hemorrhage. 4 Three publications have presented cases of extremely low intraventricular pressures of –40 cmH 2 O 5 and –20 cmH 2 O. 6 Clarke et al 5 suggest that this entity may be distinct from LPH because of the apparent impossibility of maintaining clinical improvement despite CSF drainage at subatmospheric pressures. Clarke et al 5 hypothesize that avoidance of fluid shifts might help prevent the problem. We refer to this entity as very LPH (VLPH) (or low low-pressure hydrocephalus, refractory low-pressure hydrocephalus) distinguishing it from the better known and treatable LPH. 1 Patients who have LPH can have negative pressure hydrocephalus 7 when their care is complicated by a CSF leak.

We encountered four cases of VLPH over 8 years of practice at two different institutions and two different hospitals ( Table 1 ). Most of the lesions previously reported in adults were cases of vascular pathology. Our case series differs in that all of our patients harbored suprasellar tumoral lesions; two treated with anterior skull base surgery, two with transsphenoidal surgery.

Table 1. Summary of patients in our series.

| Patient | Age/Gender | Preoperative imaging FHR When GCS is = to 15 |

Start of radiographic LPHS and FHR on day of deterioration | Start of CSF drainage and negative pressures | Number of days until recovery after diagnosis, that is, negative drainage (GCS = 15) |

Lowest level of drainage | Total # of days at hospital | Last shunt type and pressure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 40 years old male | 0.38 |

Day #71

FHR= 0.51 |

Day #84 | N/A | –5 cmH 2 0 | 171 | Right VPS, R EVD and L EVD at 5 cmH 2 0 |

| 2 | 71 years old female | 0.38 |

Day #79

FHR= 0.48 |

Day # 81 | 1 result not sustained | –5 cmH 2 0 | 121 | EVD at 5 cmH 2 0 |

| 3 | 57 years old female | 0.35 | Day #40 FHR= 0.42 |

Day #52 | 1 | –32 cmH 2 0 | 193 | Left VP shunt with programmable Strata valve set at 0.5 |

| 4 | 56 years old male |

0.32 | Day #69 FHR= 0.38 |

Day #78 | 8 | –32 cmH 2 0 | 238 | VP shunt no anti-siphon strata 0.5 |

Abbreviations: EVD---; FHR, frontal horn ratio; GCS, Glasgow Coma Score.

The first patient presented with acute hydrocephalus and his epidermoid tumor was treated via endoscopic transsphenoidal resection. Recurrent persistent infection with proteus mirabilis after inadvertent removal of urinary catheter resulted in meningitis, loculation of suprasellar abscess, and ventriculitis despite many surgical interventions to eradicate the infection. The condition of VLPH was not initially recognized.

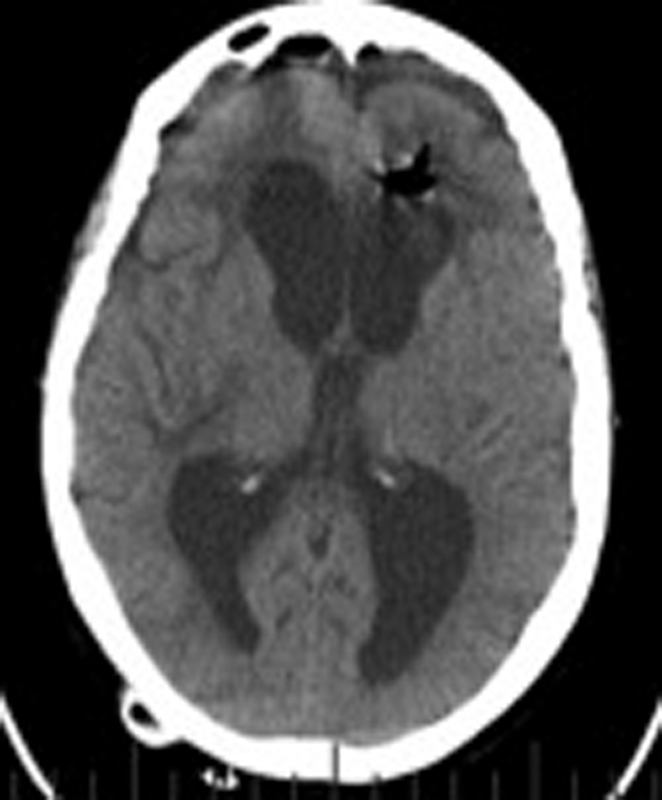

The second patient ( Figs. 1 2 3 4 5 ) presented with recurrent pituitary macroadenoma and underwent an endoscopic transsphenoidal resection that was complicated by delayed treatment of CSF leak and pneumocephalus resulting in irreversible damage from ventriculitis. The VLPH was recognized but low-pressure drainage was inconsistent.

Fig. 1.

Patient 2, recurrent macroadenoma: ( A ) T1W coronal brain MRI with gadolinium. ( B ) T1W sagittal brain MRI with gadolinium, and ( C ) T2-weighted (T2W) axial brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). (Preadmission), GCS: 15, FHR: 0.38. Abbreviations: FHR, frontal horn ratio; GCS, Glasgow Coma Score; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging. The images reflect the situation on the admission day indicated in parentheses.

Fig. 2.

Patient 2, noncontrast axial brain CT scan: Recurrent pneumocephalus. Reparation of CSF leak and EVD removed on Day #33. (Day #31) Average GCS: 12.75, FHR: 0.42, ICP: >10, EVD set to drain at 10 cmH 2 O, doesn't drain. Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CT, computed tomography; EVD, external ventricular drain; FHR, frontal horn ratio; ICP, intracranial pressure.

Fig. 3.

Patient 2, noncontrast axial brain CT scan: (Day #88) Average GCS: 12.57, FHR: 0.35, negative pressure drainage stopped on Day #84, EVD set. Inadequate negative pressure drainage. Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; FHR, frontal horn ratio; EVD, external ventricular drain; GCS, Glasgow Coma Score.

Fig. 4.

Patient 2, noncontrast axial brain CT scan: Hydrocephalus worsens: (Day #97) Average GCS: 11.75, FHR: 0.54, ICP: 0–5, EVD set to drain at 0 mmHg. Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; FHR, frontal horn ratio; EVD, external ventricular drain; GCS, Glasgow Coma Score.

Fig. 5.

Patient 2, noncontrast axial brain CT scan: Before death, (Day #108) Average GCS: 9.4, FHR: 0.47, ICP: <5, EVD set to drain at 5 cmH 2 O. Care was withdrawn on Day #121, after futile low pressure drainage. Autopsy revealed persistent pus in surgical site despite antibiotics. Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; FHR, frontal horn ratio; EVD, external ventricular drain; GCS, Glasgow Coma Score; ICP, intracranial pressure.

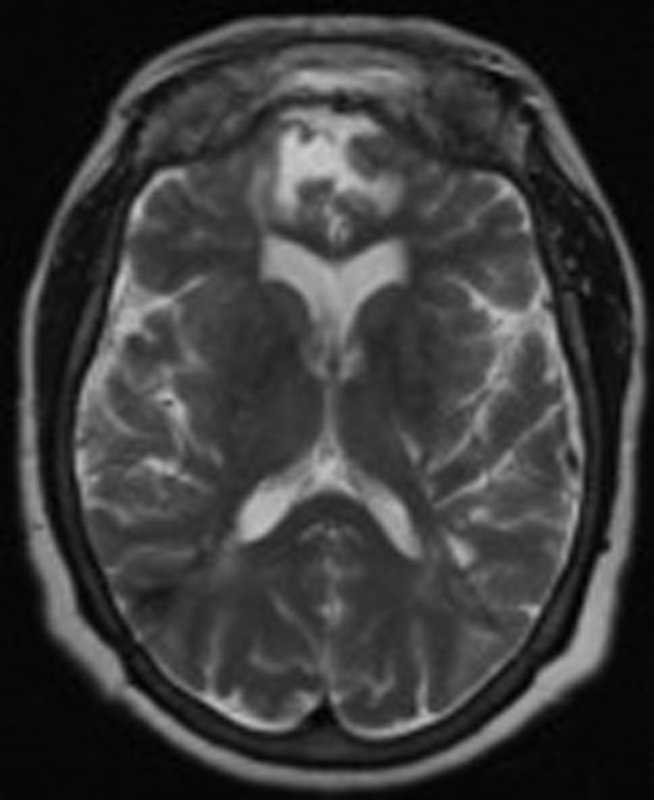

The third patient ( Figs. 6 7 8 9 10 ) presented with deterioration in vision and underwent bilateral orbitonasofrontal resection for pituitary macroadenoma. The CSF leak, immediately responsive to lumbar drainage, did not result in meningitis. VLPH was recognized early after shunt failure and treated consistently with prolonged progressive weaning of low-pressure drainage.

Fig. 6.

Patient 3, Preadmission baseline macroadenoma axial T2-weighted MRI, GCS = 15, FHR: 0.34. Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; FHR, frontal horn ratio; GCS, Glasgow Coma Score.

Fig. 7.

Patient 3, noncontrast axial brain CT scan: Had CSF leak repair and lumbar drain insertion on Day #22. (Day #52), Decreased level of consciousness, needs stimulation, periventricular edema around lateral ventricle horns, GCS: 10, FHR: 0.42, Lumbar drain set to drain at -12.5 cmH 2 O. VP shunt day: 59. Shunt revision day: 65. Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CT, computed tomography; FHR, frontal horn ratio; GCS, Glasgow Coma Score.

Fig. 8.

Patient 3, noncontrast axial brain CT scan: (Day #75) Shunt failure, average GCS: 12.57, FHR: 0.46, EVD set to drain at –5 cmH 2 O.

Fig. 9.

Patient 3, noncontrast axial brain CT scan: FHR stays closer to baseline until Day #123 (Day #123) GCS: 15, FHR: 0.4, EVD set to drain at –1 cmH 2 O. Prolonged weaning of subatmospheric drainage of CSF over 15 weeks to 5 cmH 2 O. Trial of external ventricular drainage with valve for 7 days. VP shunt on day #189, Strata valve set to 0.5, FHR: 0.41 at discharge scan. Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CT, computed tomography; EVD, external ventricular drain; FHR, frontal horn ratio; GCS, Glasgow Coma Score.

Fig. 10.

Most recent follow-up T2-weighted axial brain MRI: 2.5 years after VP shunt. Strata valve set at 0.5. GCS: 15, FHR 0.35. Abbreviations: FHR, frontal horn ratio; GCS, Glasgow Coma Score; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

The fourth patient presented with deterioration in poor baseline vision in the context of remote head trauma and prior stroke; he underwent a pterional craniotomy for the resection of newly diagnosed craniopharyngioma. He never had a CSF leak. His VLPH was recognized late and complicated by overdrainage during treatment. He survived optimization of frontal horn ratio (FHR) but succumbed to aspiration pneumonia.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review of four cases of VLPH encountered between 2007 and 2015 in two different institutions and practices and tried to identify factors contributing to improved neurologic status. We hypothesized that normalization of FHR, optimization of volume of CSF drained, and avoidance of fluid shifts would contribute to improved Glasgow Coma Scores (GCS), which we used as a rudimentary measure of neurologic status. We examined fluid shifts by studying daily levels of net fluids, and serum levels of sodium, urea, and creatinine.

From admission to death or discharge, we tabulated all the GCS that were available.

We calculated the FHR as FH/ID: frontal horns/brain parenchyma diameters at the axial computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) slice at the level of the foramen of Munro. 8 We tabulated these ratios for all the cerebral CT or MRI images available. Normal FHR ranges from 0.19 to 0.3 with an average of 0.3. 8

We also tabulated the volumes of CSF drained per day. We tabulated the correlation between volume of CSF drained per day and GCS in four subgroups: CSF drainage <150 cc/day, CSF between 150 and 200 cc/day, CSF drainage between 150 and 290cc/day, and CSF drainage >290 cc/day. We tabulated the measures of serum sodium, urea, and creatinine as well as net fluids per day. These measures were tabulated according to date.

We used Pearson correlations to evaluate linear correlations such as FHR and improving GCS. For correlations expected to be nonlinear, we used Spearman correlations to evaluate correlations between CSF drainage, serum levels of sodium, urea, and creatinine in relationship to improving GCS.

We excluded from analysis the days when the following confounding neurologic comorbidities would negatively influence GCS: meningitis, seizures, pneumocephalus, overdrainage of CSF, and postoperative anesthesia. Overdrainage was defined as occurring when FHR is lower than baseline and GCS is lower than 14.

We also studied the range of FHRs tolerated by each patient (when GCS is 14–15) as an indicator of the compliance of the brain. We compared this to the range of FHRs seen throughout the hospital stay. We expressed these ranges as a ratio of change in FHR over baseline.

Results

Section 1: Pearson Correlations between FHR and GCS

The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient ( r ) was used to evaluate the correlation between FHR and GCS. Confounding factors, which could negatively influence GCS, were removed from analysis. In patient 1, there was no statistically significant correlation between FHR and GCS. In patient 2, we found a statistically significant strong negative correlation between FHR and increasing GCS. In patients 3 and 4, we found weak negative correlations that were not statistically significant. This demonstrates a trend toward a negative correlation between FHR and GCS: neurologic improvement with decreasing ventricular size.

Section 2: Spearman Correlations between Volume of CSF Drained and GCS

While after initial study, there did not seem to be consistent correlation between volume of CSF drainage and GCS, we realized that the optimal range of CSF drainage varies between patients. For example, in the two patients who had the least compliant brain, there was a clinically significant correlation between improving GCS and increased CSF drainage (patient 2, r = 0.81, n = 6, p = 0.05 and patient 4, r = 0.62, n = 8, p = 0.1), in the range of 150–200cc per day.

The other two patients had more compliant brains. In patient 1, there was a moderately strong positive correlation between CSF drainage above 290 cc per day and improving GCS, though not statistically significant ( r = 0.5, n = 10, p = 0.14). In patient 3 ( Figs. 6 7 8 9 10 ), there was no statistically significant correlation between amount of CSF drainage and GCS. This is explained by the fact that the patient's FHRs were always in a range that permitted for a GCS of 15.

In patient 2 ( Figs. 1 2 3 4 5 ) who had the stiffest brain, good GCS was correlated with decreasing FHR as well as optimization of the volume of CSF drainage. There was a statistically significant moderately strong positive correlation between increasing CSF drainage and improving GCS. There was a very strong statistically significant positive correlation when CSF drainage was between 150 and 200cc.

Patient 3 ( Figs. 6 7 8 9 10 ) who had the most normal brain compliance relied on normalization of FHR for a good neurologic status. She responded well because she was able to maintain a GCS of 15 for most of her hospital stay as soon as the subatmospheric ventricular drainage was implemented.

Patient 4 had a brain that was prone to overdraining because of increased stiffness from prior trauma and stroke; thus, the most optimal strategy was to avoid FHR less than baseline to avoid overdrainage. There was a statistically significant moderately strong positive correlation between increasing CSF drainage and improving GCS with a particularly strong correlation when drainage was between 150 and 200cc.

Section 3: Spearman Correlations between Net Fluid Shifts, Serum Sodium, Serum Urea and Serum Creatinine, and GCS

Fluid Shifts

We found moderate negative correlations between net fluid shifts and GCS in patient 2 and patient 3. There is a trend toward increasing fluid shifts negatively influencing GCS.

Serum Sodium

In patient 2 and patient 4, weak but statistically significant correlations were found between decreasing sodium (suggestive of increasing state of hydration) and increasing GCS.

Serum Urea and Creatinine

In patient 2, whose brain was very stiff, we found a statistically significant moderate and strong negative correlation between serum urea and creatinine respectively (suggestive of increasing hydration) and increasing GCS.

In patient 3, who had the best brain compliance, and patient 4, whose brain was very stiff, we did not find a statistically significant correlation between serum urea or creatinine and GCS.

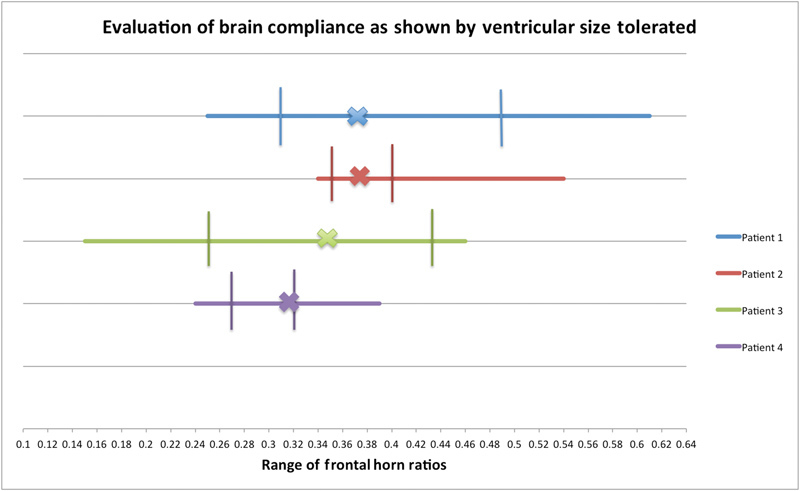

Section 4: Evaluation of Brain Compliance as Shown by Ventricular Size Tolerated

We use FHR as a measure of ventricular distension. We examined the range of FHRs documented in each patient throughout their clinical course to see if the degree of ventricular distension influenced the outcome. We compared the degree of ventricular distension associated with normal GCS to the degree of ventricular distension across all GCS values.

In Fig. 11 , we tabulated the baseline FHR and the range of FHRs found throughout the clinical course of each patient. We studied admission FHR and range of FHR for each patient. We found that good GCS could be associated with a wide variation in FHR. The patients, who had GCS that could only be maintained within a narrow variation of FHR, had poor outcomes. Our patients' change in baseline FHR ranged from 47% to 95%. However, maintenance of normal GCS was found only when patients' FHR ranged between 5% and 18% of baseline. The outcome of our patients is not dependent only on the degree of ventricular distension experienced but rather on the ability to maintain a physiologic ventricular size and a normal neurologic examination.

Fig. 11.

Evaluation of brain compliance, calculated by:

Response to treatment is not limited by variability in FHR. The vertical lines show the range in which the patients' FHR can vary while maintaining a GCS of 15. The X on each line represents each patients' baseline FHR. Poor compliance predisposes the patient to unsuccessful treatment. Patient 1 had an irreversibly floppy brain. Patient 2 had an abnormally stiff brain. Patient 3 had regained almost normal brain compliance. Patient 4 had regained his baseline brain stiffness. Abbreviations: FHR, frontal horn ratio; GCS, Glasgow Coma Score.

Response to treatment is not limited by variability in FHR. The vertical lines show the range in which the patients' FHR can vary while maintaining a GCS of 15. The X on each line represents each patients' baseline FHR. Poor compliance predisposes the patient to unsuccessful treatment. Patient 1 had an irreversibly floppy brain. Patient 2 had an abnormally stiff brain. Patient 3 had regained almost normal brain compliance. Patient 4 had regained his baseline brain stiffness. Abbreviations: FHR, frontal horn ratio; GCS, Glasgow Coma Score.

Discussion

There have only been three reported cases of VLPH as defined by necessity of drainage at or lower than –20 cmH20. Prior authors 5 6 reported extremely poor outcomes, difficulty in maintaining ventricular size as well as neurologic improvement and experienced challenges in maintaining drainage at sufficiently low pressures. They suggest that this entity is distinguishable from LPH which is generally thought to be reversible. Hamilton, 2 however, describes a case of good recovery after successful treatment of tuberculosis meningoencephalitis.

We describe four cases and demonstrate a learning curve that is involved in care of these patients. We feel that in adult patients several challenges were encountered. Delay in diagnosis, distinction of clinical deterioration from other concurrent comorbidities or conditions (SIADH [syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion], pneumonia, UTI [urinary tract infection], sepsis, etc.), and neurologic deterioration from other causes such as post-op anesthesia, CSF leak, meningitis, ventriculitis, seizures, CSF overdrainage, CSF under drainage, and concurrent use of PEEP. Delay in sealing any CSF leak can render the care even more difficult due to the development of negative pressure hydrocephalus.

Despite these challenges we try to define some measures which would help guide us along the course of treatment and help us determine how to recognize if treatment is futile. Regardless of intercurrent illnesses, if FHR returns to baseline, and the thickness of the cortical mantle and the subarachnoid space are restored, we feel that a more favorable neurologic status should return and be sustainable. If this is not possible, then we feel that the brain parenchyma has suffered irreparable damage and no further futile efforts to drain CSF should be attempted. In our patients, the permanent change in brain compliance was caused by permanently altered brain viscoelasticity secondary to unsuccessful treatment of loculated suprasellar brain abscess and ventriculitis, delay in sealing CSF leaks leading to pneumocephalus and ventriculitis, and numerous repeated surgeries to treat the infections.

The first two patients suffered from delay in the treatment of the CSF leak: unsuccessful treatment of ventriculitis and delay in recognition of the entity VLPH. Longer duration of drainage, lower atmospheric drainage, and slow, gradual weaning may result in more successful outcomes. More intercurrent surgeries and severe comorbidities may have precluded healing. Their brain elasticity was permanently altered and the restoration of cortical mantle thickness could not be maintained or even when maintained did not result in satisfactory neurologic improvement. Removal of the cervical collar in patient 1 resulted in sudden demise.

Patient 3, the only long-term survivor, was discharged home. Patient 3′s positive outcome was also due to immediate and successful treatment of the CSF leak and meningitis. In consequence, the resolution of LPH was solely dependent on adequacy of subatmospheric drainage.

Patient 4 had underlying problems in brain compliance due to prior remote head trauma and recent stroke. The beginning of drainage was delayed and he was extremely sensitive to overdrainage. Though he returned to even better than baseline status in long-term care, he was afflicted with pneumonia, which caused his demise a few months after discharge.

Our study reveals that improving GCS is positively correlated with decreased FHR and increased CSF drainage within an optimal range. The most important determinant of functional neurologic outcome or return to baseline is retention of brain viscoelasticity as evidenced by restoration and maintenance of good GCS score despite fluctuations in ventricular size as measured by FHR. Fluid shifts as reflected by magnitude of change in net fluids seemed to negatively influence GCS. Decrease in serum sodium within a physiologic range seemed to improve GCS.

Decrease in urea, and creatinine, reflecting level of hydration only affected GCS if brain compliance was lost.

Maintenance of good GCS seemed to depend on optimization of volume of CSF drained aiming for FHR as close to baseline as possible.

Conclusion

LPH is often missed and its treatment is fraught with challenges. VLPH, as defined by severity of initial negative pressure (lower than—20 cmH 2 O) in the ventricles, does not in and of itself predict the impossibility of treatment. The futility of treatment is discernable when prolonged subatmospheric drainage cannot restore and maintain the brain's normal elasticity. In our examples, permanently altered brain viscoelasticity was secondary to irremediable unsealed CSF leaks, ventriculitis, and repeated surgeries. Subsequently, the patients were unable to maintain a normal FHR and sustain an improved neurologic examination. Treatable conditions for our patients included the ability to wean the patient off the use of a cervical collar, satisfactory control of seizures, and successful treatment of meningitis. We conclude that restoration of FHR to baseline, by consistent attention to volume of CSF drained and minimization of fluid shifts can be excellent measures to restore and sustain neurologic improvement.

References

- 1.Pang D, Altschuler E.Low-pressure hydrocephalic state and viscoelastic alterations in the brain Neurosurgery 19943504643–655., discussion 655–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamilton M G, Price A V. Syndrome of inappropriately low-pressure acute hydrocephalus (SILPAH) Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 2012;113:155–159. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0923-6_31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rekate H L, Nadkarni T D, Wallace D. The importance of the cortical subarachnoid space in understanding hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;2(01):1–11. doi: 10.3171/PED/2008/2/7/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akins P T, Guppy K H, Axelrod Y V, Chakrabarti I, Silverthorn J, Williams A R. The genesis of low pressure hydrocephalus. Neurocrit Care. 2011;15(03):461–468. doi: 10.1007/s12028-011-9543-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke M J, Maher C O, Nothdurft G, Meyer F. Very low pressure hydrocephalus. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 2006;105(03):475–478. doi: 10.3171/jns.2006.105.3.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filippidis A S, Kalani M Y, Nakaji P, Rekate H L. Negative-pressure and low-pressure hydrocephalus: the role of cerebrospinal fluid leaks resulting from surgical approaches to the cranial base. J Neurosurg. 2011;115(05):1031–1037. doi: 10.3171/2011.6.JNS101504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vassilyadi M, Farmer J P, Montes J L. Negative-pressure hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg. 1995;83(03):486–490. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.83.3.0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hahn F JY, Rim K. Frontal ventricular dimensions on normal computed tomography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1976;126(03):593–596. doi: 10.2214/ajr.126.3.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]