Abstract

Hypoxia-mediated tumor progression, metastasis, and drug resistance are major clinical challenges in ovarian cancer. Exosomes released in the hypoxic tumor microenvironment may contribute to these challenges by transferring signaling proteins between cancer cells and normal cells. We observed that ovarian cancer cells exposed to hypoxia significantly increased their exosome release by up-regulating Rab27a, down-regulating Rab7, LAMP1/2, NEU-1, and also by promoting a more secretory lysosomal phenotype. STAT3 knockdown in ovarian cancer cells reduced exosome release by altering the Rab family proteins Rab7 and Rab27a under hypoxic conditions. We also found that exosomes from patient-derived ascites ovarian cancer cell lines cultured under hypoxic conditions carried more potent oncogenic proteins - STAT3 and FAS that are capable of significantly increasing cell migration/invasion and chemo-resistance in vitro and tumor progression/metastasis in vivo. Hypoxic ovarian cancer cells derived exosomes (HEx) are proficient in re-programming the immortalized fallopian tube secretory epithelial cells (FT) to become pro-tumorigenic in mouse fallopian tubes. In addition, cisplatin efflux via exosomes was significantly increased in ovarian cancer cells under hypoxic conditions. Co-culture of HEx with tumor cells led to significantly decreased dsDNA damage and increased cell survival in response to cisplatin treatment. Blocking exosome release by known inhibitor Amiloride or STAT3 inhibitor and treating with cisplatin resulted in a significant increase in apoptosis, decreased colony formation and proliferation. Our results demonstrate that HEx are more potent in augmenting metastasis/chemotherapy resistance in ovarian cancer, and may serve as a novel mechanism for tumor metastasis, chemo-resistance and a point of intervention for improving clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Ovarian cancer, hypoxia, exosomes, STAT3, chemoresistance

Introduction

Hypoxia is considered a critical factor in promoting the spread of epithelial tumors1. Hypoxic ovarian cancer demonstrates an aggressive phenotype that includes increased drug resistance and an associated poor clinical outcome2, 3, 4, 5. The hypoxic tumor microenvironment favors the secretion of various chemokines that impact nearby tissues6. It is well-known that all eukaryotic cells stay in contact with their local environment by transporting biological material across membranes via the secretion of small vesicles called “exosomes” that are endocytic in origin (40 – 100 nm in size)7, 8.

Research over the last few decades has revealed new facets of the role played by the exosomes in the development and progression of many diseases, including cancer9. Aberrant activity of export machinery leads to expulsion of many proteins, RNAs10, and microRNAs (miRs)11, 12 in pathological conditions such as cancer. These cell contents, when transferred to recipient cells, can alter its biologic behavior, including intracellular signaling pathways10. Exosomal contents, therefore, have the ability to act as either tumor suppressors or promoters through their direct actions on a cell or by modifying the microenvironment13, 14, 15.

Rab proteins are a large family of small GTPases that play an important role in exosome secretion from cells. Previous work has shown that Rab27a and Rab27b act as key regulators of exosome secretion, and are involved in cancer progression and tumor metastasis16. In addition, lysosomes serve as important organelles regulating the exosome secretion. Further, lysosomal changes in size, volume, and phenotype (Degradative/Secretory) in cancer cells can lead to drug-resistance17, 18. As an example, changes in the lysosomal and exosomal pathways observed in cisplatin-resistant cells can increase the efflux of cisplatin, lowering the intracellular concentration of this drug19.

We have shown previously that the oncogenic transcription factor STAT3 is highly activated under hypoxia by HIF-1α in ovarian cancer3, 20. Therefore, we sought to investigate whether STAT3 is physically transported by exosomes and/or regulates the release of exosomes. We also examined whether the proteins released from cancer cells by exosomes are capable of affecting tumor progression, metastasis and resistance in recipient cancer cells. In addition, we evaluated whether exosomes isolated from primary ovarian cancer cell lines are capable of altering or reprogramming normal mouse fallopian tube secretory cells to pro-tumorigenic form.

Results

Isolation, characterization and proteome profiling of normoxic ovarian cancer cells derived exosomes (NEx) and hypoxic ovarian cancer cells derived exosomes (HEx)

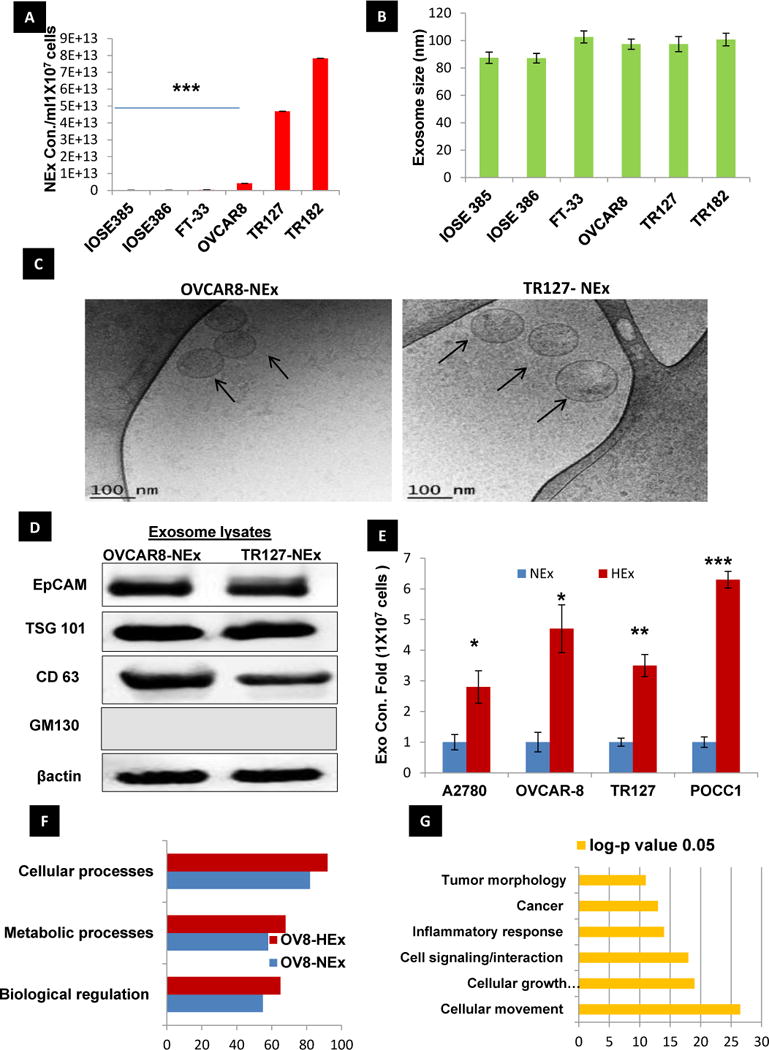

Exosomes isolated from immortalized ovarian surface epithelial cells (OSE385, 386) and fallopian tube secretory cells (FT-33), and ovarian cancer cell lines (OVCAR8, TR127, and TR182) were quantified for their concentration and size by NTA and normalized to the total cell count in each cell lines used. The size of the isolated exosomes (30 to 120nm) was within the expected range in all the cell lines. Exosome concentration was significantly higher in the cancer cell lines compared to immortalized ovarian epithelial cells (IOSE-385& 386) and FT-33 (Fig.1A&B). Visual confirmation on the size and morphology were done using cryo-TEM (Fig.1C, Sup. Fig. 1A) in different cell lines. In addition, the presence of exosome surface markers such as EpCAM, TSG101, and CD63 along with cis-golgi protein GM-130 for vesicle purity was confirmed in the exosome lysates isolated from different cell lines (OVCAR8 and TR127) in normoxia by western blots (Fig.1D). Since ovarian cancer is hypoxic in nature, the effects of oxygen tension on the release of exosomes from ovarian cancer cells were assessed by incubating cells for 48 h (in exosome-free culture medium) in Normoxia (20% O2 and under an atmosphere of 5% CO2-balanced N2 to obtain 1% O2 in an automated hypoxia chamber (BioSpherics™, Lacona, NY, USA). Cell number and viability was determined after each experimental treatment by Trypan Blue exclusion (data not shown).The fold change in the exosome release from different cell lines ranged from 2-6 fold increase in hypoxia compared to normoxia across different cell lines with the maximal fold change observed in the primary ovarian cancer cells derived from patient ascites.(Fig.1E). As exosomes are known to carry biological information from host cells and also play an important role in intercellular communication in the tumor microenvironment, we analyzed the proteomic profile of the exosomes isolated from cancer cells and immortalized ovarian epithelial cells using ID-LC-MS/MS, that is represented as base peak for normoxic and hypoxic exosomes showing significant overlaps of proteins (Sup. Fig. 1B, Sup. Table 1), showing differential expression in HEx. Of the top proteins, Gene Ontology (GO Term) analysis revealed 90% of the total exosome proteins from both NEx and HEx were related to cellular processes, 70% to metabolic functions and 60% biological regulations in HEx (Fig. 1F, Sup. Fig.2A). Gene symbols for our exosomes protein dataset were identified and subjected to Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) and identified STAT3 as the top regulator effector network (Sup. Table 2) that was predicted to be activated downstream of the TGFβ network (Sup. Fig. 2B). Also 135 molecules from our protein dataset in the exosomes, were associated with cancer (Fig.1G) among the top diseases and biological functions. Overall, these results suggest that HEx carry diverse protein cargo that could be associated with tumor progression, metastasis and resistance.

Fig 1. Isolation and characterization of exosomes.

A,B) The concentration of exosomes released is higher in immortalized and primary ovarian cancer cells than normal epithelial and FT cells normalized to the respective cell counts (n=3±SD) as measured by NanoSight analysis. The Size mode: 105 nm averaged from three technical replicates for each sample(n=3±SD). C) Cryo-TEM images of the exosomes isolated from OVCAR8 and TR127 cells (Scale bar-100nm) D) Confirmation of exosome specific markers such as EPCAM, CD-63, TSG-101 and GM130 and a cis-Golgi apparatus protein for validation of vesicle purity in the exosome preparation, confirmed by Western Blot. E) Fold change in the exosome concentration isolated from different ovarian cancer cell lines and primary ovarian cancer cells (POCC) cultured in normoxia (20%O2) and hypoxia (1%O2) (n=3±SD; *p-value,0.05, ** 0.005, *** 0.0001). F) Gene Ontology (GO) Term analysis of the exosome protein data set shows that most of the exosomal proteins are related to cellular processes, metabolic processes and biological regulation in the hypoxia exosomes when compared with the normoxia exosomes from OVCAR8 cells(p<0.05). G) Ingenuity pathway analysis of the exosome proteome data set shows the list of biomolecules identified in the dataset to be associated in top six different diseases and functions. Fisher’s exact test was applied to calculate significance (p<0.05).

Secretory lysosomal phenotype favors exosome release in hypoxia

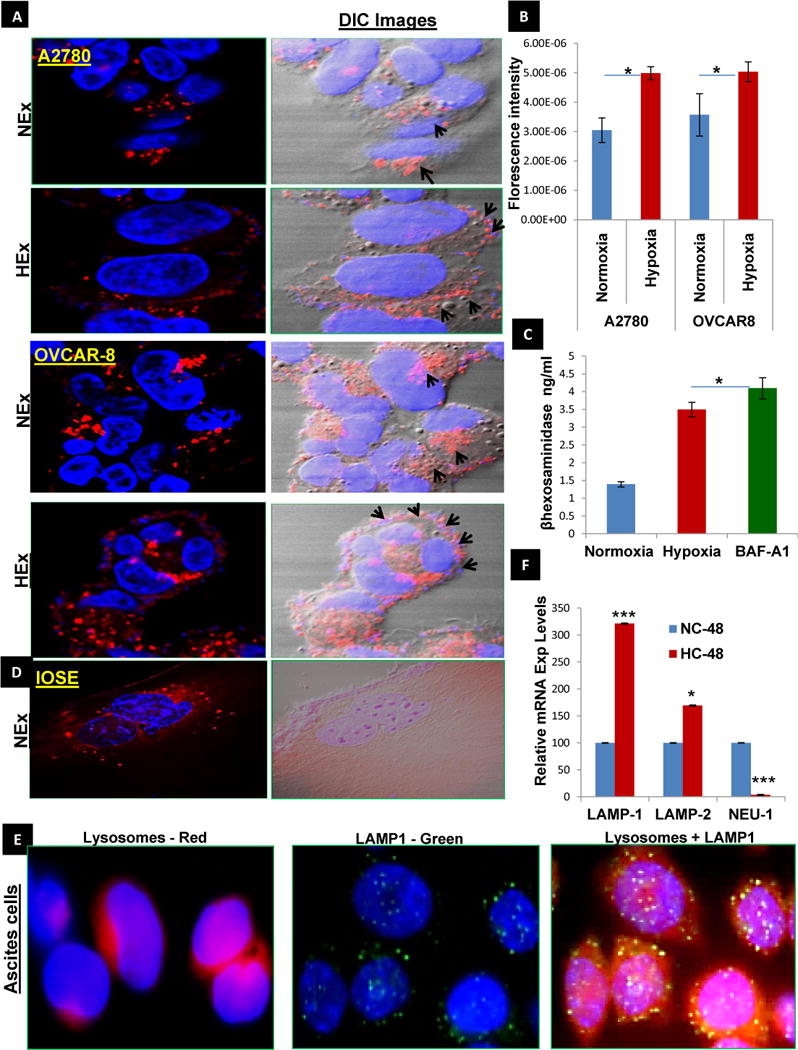

Having confirmed that hypoxia induces a) increased exosome release from ovarian cancer cells and b) increased/altered protein content in those exosomes, we next focused on investigating the changes in the lysosomes as they are important organelles involved in the exosome trafficking pathway. More of a peripheral lysosomal localization and docking towards the plasma membrane was observed using the lyso-tracker –Red in hypoxic A2780 and OVCAR-8 cells and their increased fluorescence intensity quantified by ImageJ (Fig.2A&B). Further, the lysosomal docking that might lead to its exocytosis was confirmed by the concentration lysosomal hydrolase- B-Hexosaminidase-A in cell culture media in hypoxia when compared to that in Normoxia (Fig. 2C). On the contrary the IOSE cells showed only a perinuclear distribution of the lysosomes (Fig. 2D). In addition the real time gene expression of transcription factor EB (TFEB) that enhances lysosomal exocytosis (Supp. Fig. 3A &B) was also increased under hypoxia along with the increase in lysosome associated calcium channel mucolipin-1(MCOLN-1) expression that also augments exosome release through the lysosomal exocytosis promoting cellular clearance under hypoxia.

Fig.2. Hypoxia favors increased lysosomal docking to the plasma membrane.

A&B) The lysosomes labelled using the lyso-tracker Red dye visualized by confocal microscopy in ovarian cancer cell lines (A2780 and OVCAR-8) show a perinuclear localization in normoxia and a peripheral orientation favoring the docking to the plasma membrane in hypoxia, confirming a more secretory phenotype (60×) with higher fluorescence intensity in hypoxic cells than the normoxic cells as quantified by Image J (n=3±SD; p<0.01). C). B-Hexosaminidase A concentration as a measure of lysosomal exocytosis by Competitve ELISA method shows increased concentration in Hypoxia and was further confirmed by the treatment of OVCAR8 with Bafilomycin –A1(autophagy inhibitor) (1μM for 24 hr) Vs Normoxia (n=3±SD; p<0.05 using student t-test). D) The ovarian surface epithelial cells (OSE) show a perinuclear localization of the lysosomes in normoxia. E) The peripheral lysosome co-localization (red) with LAMP-1(green) was further confirmed in cells isolated from patient ascites, which is a hypoxic environment. F) The real time gene expressions of LAMP1&2 in 48 hr period in hypoxia (HC-48) were increased when compared to normoxia (NC-48). Further the downregulated mRNA expression of Neuraminidase 1 (a negative regulator of lysosomal exocytosis) as observed in hypoxia causes the accumulation of oversialylated LAMP’s favoring the movement of lysosomes to the periphery of the cell (n=3±SD; p<0.001) using student t-test).

Additionally, the co-localization of lysosome associated membrane protein-1 (LAMP1), a lysosome membrane protein with Lysosomes stained with lyso-tracker red by Fluorescence microscopy confirmed the peripheral distribution of the lysosomes in the cells isolated from patient ascites (hypoxic environment) with ovarian cancer(Fig.2E). This demonstrates the clinical correlation of the secretory phenotype of the lysosomes that was observed under hypoxia in in-vitro. Further the protein expressions of LAMP1/2 (Supp. Fig. 3C) were then analyzed in plasma membrane and cytosolic fractions of OVCAR-8 cells cultured under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. LAMP1/2 protein levels were decreased, while mRNA expression levels were increased, in hypoxic conditions compared to normoxia (Fig. 2F). This implies a possible post-translational modification may lead to decreased LAMP1/2 protein expression inside the cells, which then leads to increased exosomal release under hypoxic conditions. Since sialylated LAMP1 promotes lysosomal fusion to the cellular membrane leading to lysosomal exocytosis, we measured real time expression of Neuraminidase-1 (NEU-1) which negatively regulates the sialylation of the LAMP1 and observed its downregulation in hypoxia signifying (Fig. 2F) its role in lysosomal exocytosis. Additionally, in cancer cells under hypoxia we observed high mRNA expression of serpin-spi2A (Sup. Fig. 4A), a lysosomal protease inhibitor that is known to prevent the formation of leaky lysosomes. This observation clinically correlated well with high protein expression levels of spi2A in human ovarian cancer tissues when compared to benign and normal ovarian tissues (Sup. Fig. 4B).The higher expression of spi2A may favor the secretory role of lysosomes in ovarian tumor tissue. Our results suggest that downregulated NEU-1 mRNA levels in hypoxia could increase the accumulation of sialylated LAMP1, favoring lysosomal docking to the plasma membrane.

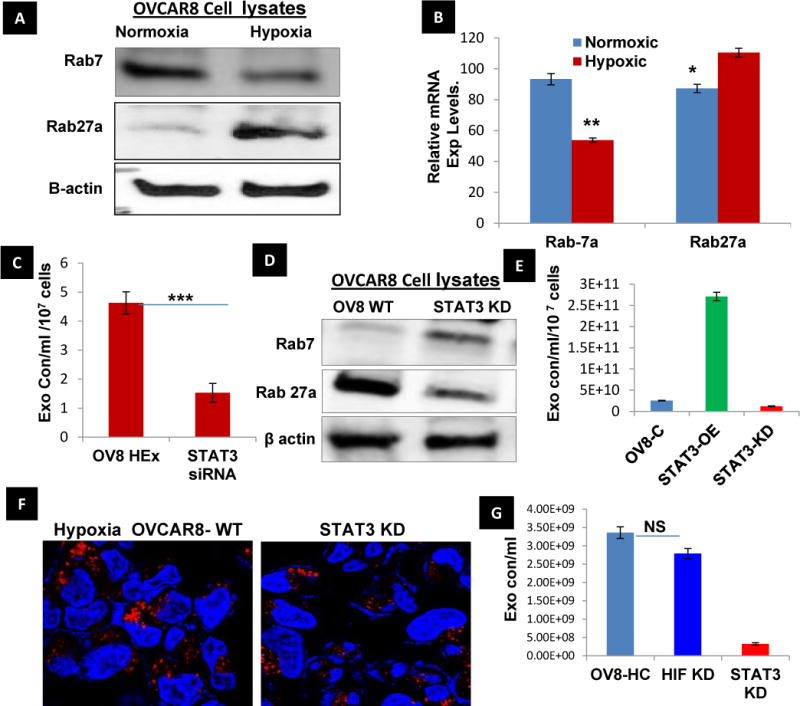

Evaluating the role of Rabs and STAT3 in exosome release

Given the central role of Rab- GTPases in regulating multiple steps of vesicle trafficking, we analyzed Rab GTPases such as Rab5a, c and Rab15.These Rab GTPases are involved in early endosome formation and recycling. We also examined Rab7, a pivotal protein in endolysosomal fusion, and Rab27, a regulator of late endosome docking with the plasma membrane. QT-PCR analyses revealed increased Rab5a, c that are specific for endosome formation and an opposing effect of Rab15 indicative of reduced recycling (Sup. Fig.5A). Further, in hypoxia, protein and mRNA expression was inversely correlated for Rab7 and Rab27 (Fig. 3A & B), that favor the docking of the multivesicular bodies (MVBs) at the plasma membrane by reducing the endolysosomal fusion. This was confirmed by the increase in B-Hexosaminidase concentration on treatment of OVCAR8 with Bafilomycin-A1 a known autophagy inhibitor that inhibits the fusion of late endosomes with lysosomes as previously shown in Fig. 2C. We did observe similar results in ovarian cancer patient tissues samples, showing Rab27a being consistently expressed while Rab7 showing low or no expression (Supp.Fig.5C). In relevance to the top regulatory network identified in our data set by IPA that shows the predicted activation of STAT3 in HEx, we have also observed constitutive expression of pSTAT3 in ovarian cancer patient tissues samples and hypoxic ovarian cancer cell lines20, 21 (Supp. Fig.5C), indicating that STAT3 activation might have a role in the exosome secretion pathway. Our results confirm a significant decrease in the exosome concentration in STAT3 knock down (Fig.3C & Sup.Fig.5B) in OVCAR-8 cells under hypoxia. Added to the previous results, the knockdown of STAT3 altered the Rab family proteins (Rab7 & 27a) (Fig. 3D), suggesting a role for STAT3 in vesicular trafficking in ovarian cancer cells. The exosome concentration in OVCAR8 cells measured using both positive and negative controls for STAT3 OE and KD indicated a plausible role for STAT3 in the exosome pathway Fig. 3E. Also a significant decrease in lysosome numbers in STAT3- KD cells were observed (Fig. 3F) suggesting a role for STAT3 in lysosomes biogenesis and vesicular trafficking in ovarian cancer cells. Further we measured the exosome concentration in HIF-1α KD cells and confirmed that the exosome release was significantly influenced by STAT3 KD rather than hypoxia itself (Fig. 3G). All of the above results converge on the idea that the lysosomal phenotype leads to increased exosome release mediated by the Rab-GTPases through the activation of STAT3 in hypoxia.

Fig.3. Alteration of Rabs and LAMPs expression under hypoxia: STAT3 regulated Rab7& 27a in vesicular trafficking.

A, B) The protein and mRNA expression of Rab GTPase 7 and 27a were found to be inversely proportional in both Normoxia and hypoxia observed after 48 hr. The reduced Rab7 might reduce the endo-lysosomal fusion augmenting the lysosomal exocytosis which is further supported by increased Rab27a to release the exosomes in hypoxia (n=3±SD; p<0.05 using student t-test). C) The role of STAT3 in the exosome pathway was confirmed by measuring the exosome concentration isolated from STAT3 knockdown OVCAR-8 cells cultured in hypoxia for 48 hour and compared with the wild type OVCAR8 in Hypoxia (n=3±SD; p<0.005 using student t-test). D) The knockdown of STAT3 significantly increased the expression of RAb7 and decreased Rab27a when compared to OVCAR8 WT (hypoxia) demonstrating its role regulating the Rab GTPases involved in vesicle trafficking. E) Exosome concentration measured in STAT3-OE and KD OVCAR8 ells show the significant increase and decrease in the exosome concentration (n=3±SD). F) Also STAT3 knockdown cells showed a significant decrease of lysosomal numbers indicating its putative role in lysosome biogenesis under hypoxia. G. Exosomes concentrations were measured in HIF1α KD and STAT3 KD, no significance changes observed in HIF1 KD cells (n=3±SD).

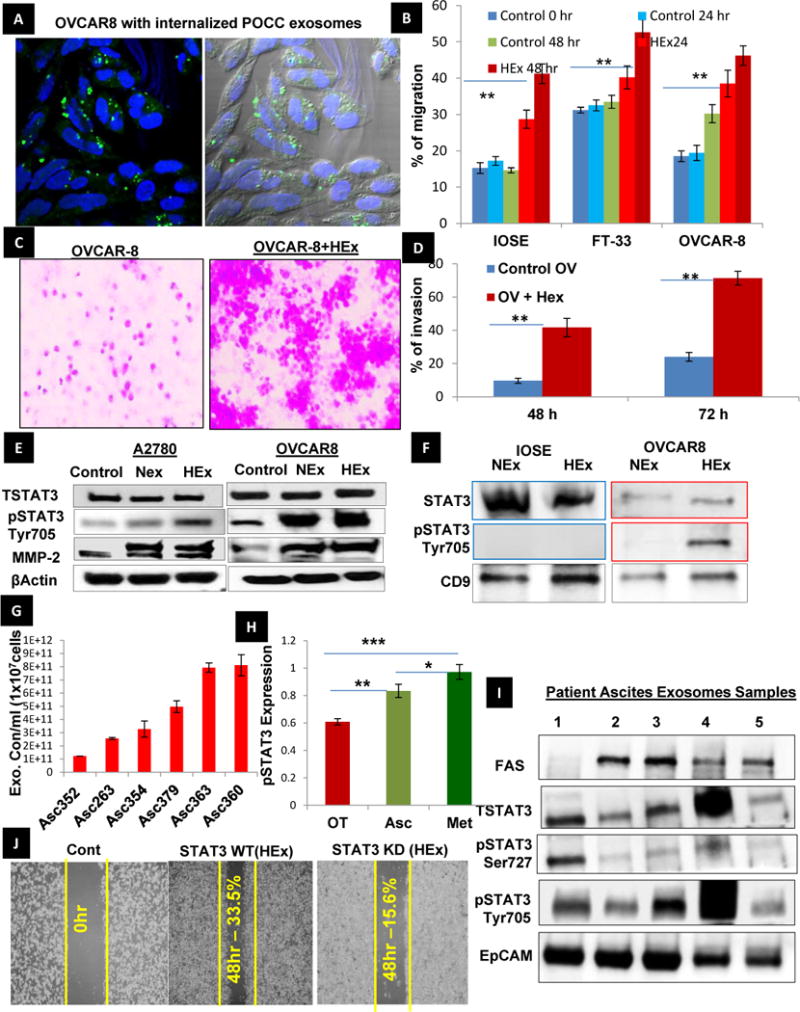

Evaluating the effect of HEx in migration/invasion in vitro

We next investigated whether HEx mediate the transfer of biological information to their recipient cells. To address this question, we i) isolated exosomes from patient derived primary ovarian cancer cells, ii) labeled the exosomes with exo-glow green, iii) used confocal microscopy to view internalization of the labeled POCC exosomes by co-culturing them with OVCAR-8 cells (Fig. 4A), and iv). We found that NEx or Hex (20μg protein on alternate days), when co-cultured with other ovarian cancer cells for a week, ovarian surface epithelial cells, or fallopian tube secretory cells (OVCAR-8, IOSE and FT respectively), had a significant impact on cellular migration shown by wound healing assay (Fig. 4B, Sup. Fig. 6A–C) In addition, co-culture of OVCAR-8 cells with 20μg Hex for 48 hr was associated with a significant increase in invasion potential, as observed using Transwell cell invasion kit. (Fig. 4C&D & Sup. Fig. 6D). A2780 and OVCAR-8 cells co-cultured with NEx and HEx were also associated with an increase levels of oncogenic proteins (such as pSTAT3-Y705) and proteins involved in migration/invasion (e.g., MMP 2) in the recipient cancer cells (Fig. 4E). Also we further confirmed the expression of STAT3 within the exosomes of IOSE and OVCAR-8 cell lines was confirmed; interestingly, its activated form was observed only within the exosomes isolated from OVCAR-8 in hypoxia (Fig. 4F). High levels of exosome concentration was released from cells isolated from different patient ascites which is considered to be an hypoxic tumor microenvironment when compared to those quantified from the immortalized cancer cells normalized to their cell counts (Fig.4G, Sup.Fig.7). In relevance to the observation of pSTAT3expression in cancer cells under hypoxia, a significant elevation of pSTAT3 Tyr705 in ascites and metastasis than in the primary tissue of ovarian cancer obtained from the same patient (Fig. 4H) indicates its importance in the spread of the disease. Moreover increased pSTAT3 and FAS expression observed in the exosomes isolated from ovarian cancer patient ascites samples that reflects the hypoxic microenvironment (Fig.4I) also added to its influence the cell migration/invasion in the recipient cells. This was further confirmed by the decrease in the migratory potential of the exosomes isolated from STAT3 KD cells when compared to exosomes from the STAT3 WT cells when co-cultured with the recipient cells (Fig. 4J). These results suggest that HEx are in part responsible for the increased migratory and invasive potential of recipient cancer cells by the transfer of oncogenic protein- STAT3 to the recipient cells.

Fig. 4. Exosome internalization and its influence on the tumor migration and metastasis in the recipient cells.

A) Exosomes isolated from hypoxic ovarian cancer cells were labelled with exo-glow- green, which labels the proteins inside the exosomes, and co-cultured with the OVCAR-8 ovarian cancer cells in conditioned medium. The exosome internalization after 24 hrs was confirmed by confocal microscopy. The differential contrast image (DIC) shows that exosomes are internalized. B) The percentage of migration was quantified using Image J software in normal (OSE and FT-33 cells) and ovarian cancer cell lines (OVCAR-8) with and without HEx co-culture (n=3±SD; p<0.05 using student t-test). C &D) Invasive potential of the OVCAR-8 cells was analyzed using cell invasion transwell assay kit. The number of cells invading the membrane was significantly increased after 48 and 72hr when co-cultured with HEx and quantified as percentage of invasion as shown (n=3±SD; p<0.005 using student t-test. E) NEx and Hex(20μg on alternate days) was co-cultured with A2780 and OVCAR-8 cells in conditioned medium under normoxia for a week and observed an increase in the protein expression of activated STAT3 and proteins involved in tumor progression and metastasis-MMP2. F) To investigate the transport of STAT3 via exosomes the expression of STAT3 in the IOSE and cancer cell exosomes showed the presence of pSTAT3 in the exosomes derived from cancer cell line(OVCAR8) but absent in normal cell (IOSE) exosomes, though the total STAT3 was seen in both normal and cancer cell exosomes. G), The primary cells isolated from different patient ascites (n=6± SD, Stage IV) were cultured in conditioned medium for 48hrs and the exosome concentration measured by NTA showed higher magnitude (1011) of exosome release when compared to the magnitude released from immortalize cancer cells(109) in Normoxia, normalized to their respective cell counts(107). H) pSTAT3 expression in primary ovarian tumor tissues, ascites and metastatic tissues (n=3±SD, *p<0.05, ** p<0.005) from the same patient show increased STAT3 activation in the ascites and metastatic sites than the primary tumor site implying the role of STAT3 in tumor progression and metastasis. I) The expression of oncoproteins such as STAT3, pSTAT3, and FAS were confirmed in the exosomes isolated from patient ascites normalized to the EpCam expression. J) Migration assay proved the role of exosomal STAT3 using exosomes isolated from both STAT3 WT and STAT3 knock down (KD) cells. The OVCAR8 cells co-cultured with exosomes from STAT3 KD cells for 48 hrs significantly decreased the migration potential of OVCAR- 8 cells.

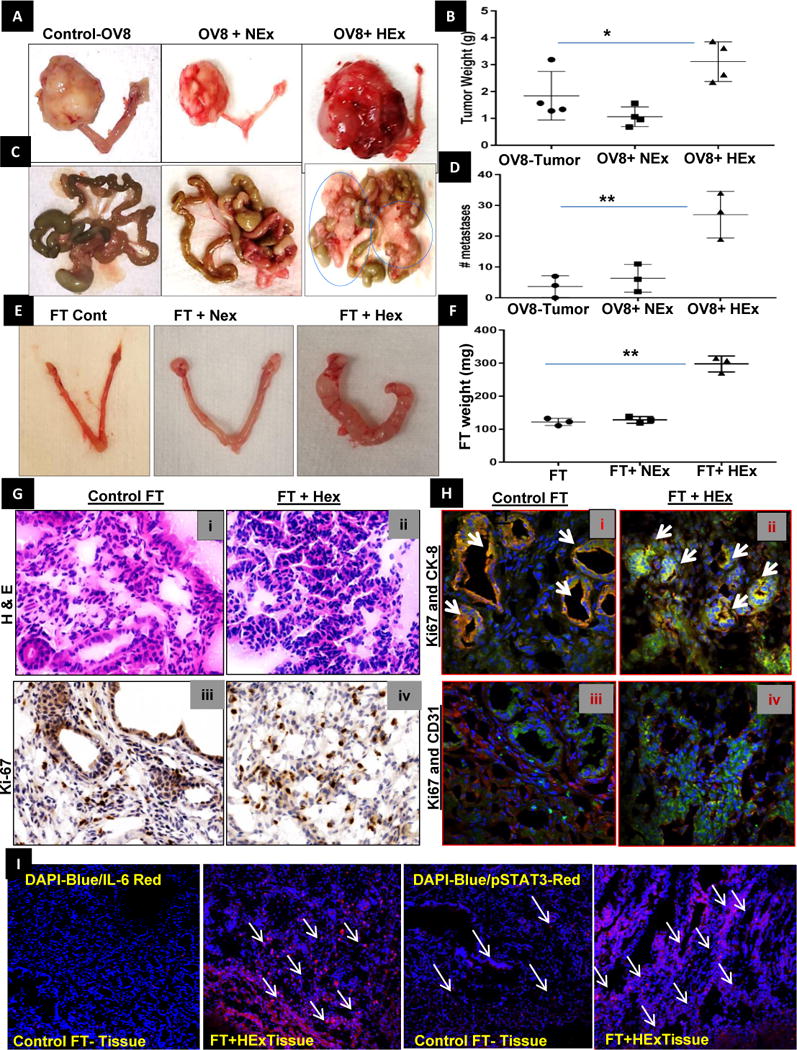

Evaluating the tumor progression and metastatic potential of HEx in vivo using an orthotopic ovarian tumor model

To evaluate the aforementioned results in vivo, we used orthotopic ovarian tumor model. This model consisted of OVCAR-8 ovarian cancer cells—co-cultured with NEx or HEx isolated from primary ovarian cancer cells (POCC) (20μg) on alternate days for three weeks and then the exosome treated OVCAR8 cells were injected into the ovarian bursa and observed for the tumors in vivo for four weeks. The mice injected with OVCAR-8 cells co-cultured with HEx had significantly greater tumor growth and the presence of numerous metastatic nodules in the mesentery than the same cells cultured with NEx. (Fig. 5A–D). No significant changes were observed in the body weight of these mice (Sup. Fig.8A&B). We observed a significant increase in the serum exosome concentration, along with the protein expression of pSTAT3 and MMP2/9 in the ovarian tissue of HEx treated mice group (Sup. Fig. 8C, D&E). Similarly, when FT cells treated the same way as mentioned above by POCC exosomes and injected into the ovarian bursa, an increase in the size and weight of the fallopian tubes was seen (Fig. 5E & F). Hematoxylin–Eosin staining of the fallopian tubes of HEx treated mice showed hyperplasia (Fig.5G i, ii) that was confirmed by increased cell proliferation marker-Ki67 (Fig. 5G iii, iv & Sup. Fig: 10A&B). In addition, immunofluorescent double-labeling performed in frozen tissue sections from control and HEx treated fallopian tube showed increased Ki67 co-localization with the glandular epithelial cell specific marker cytokeratin8 (CK8) showing epithelial specificity in the proliferating cells and increased endothelial marker CD31 (Fig. 5H-i-iv) demonstrating the capability of HEx to increase the angiogenic potential in mice fallopian tube cells. Further, the expression of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 along with pSTAT3 was also increased in the fallopian tubes of HEx treated mice (Fig. 5I, Sup. Fig.11). Interestingly, we found that some of the genes involved in cell proliferation (STAT3, CycD1, CMyc, HGF) and tumor migration/invasion (MMP-2) that reflected in their protein expression as well in the fallopian tube tissues and in the serum of the mice injected with FT cells treated with HEx (Sup. Fig.8F, G & 9) when compared to their respective control mice. These results show that exosomes are carriers of oncogenic proteins and can alter the signaling pathways in the recipient cells by transfer of proteins, and that hypoxia induces changes in exosomes that can a) enhance the malignant phenotype of recipient cancer cells and b) promote cancer-like behavior of non-cancer cells.

Fig. 5. HEx enhance tumor metastasis and is capable of reprogramming normal cells.

A, B) The ovarian bursa of mice were injected with POCC exosome treated OVCAR-8 cells after three weeks of co-culturing with NEx and Hex (20 μg on alternate days). The tumor weights were significantly increased after four weeks in OV8HEx injected mice than NEx or control OVCAR-8 injected mice as represented by dot plots (n=4±SD). C, D) The number of metastatic nodules were significantly higher in mice injected with OVCAR-8 cells, which were co-cultured HEx than in NEx and the control in the dot plot (n=3±SD, * p<0.05, **p<0.005). E) A similar experiment was done in mice injected with fallopian tube secretory cells that were co-cultured with NEx and Hex (20 μg on alternate days) for three weeks to see the capability of the exosomes to reprogram FT cells. No tumors were observed after four weeks but a significant change in the morphology of the fallopian tube was observed in all the mice injected with FT cells previously co-cultured with HEx for four weeks. F) The weight of the fallopian tube with the ovary was significantly higher in the HEx when compared to the NEx or control as represented by dot plots (n=3±SD). G) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections of (i) control mouse fallopian tube (FT) injected with immortalized FT cells; surface epithelium and glands spaced by stroma are seen. There is no cellular atypia; (ii) H&E stained sections of FT after injection of HEx treated FT cells. There is confluent epithelial proliferation with absence of intervening stroma. Atypical pleomorphic nuclei are identified. Ki67 staining of (iii) control mouse FT injected with immortalized FT cells shows scant nuclear labeling when compared to iv) FT section after injection of HEx treated FT cells mice. Each image shown at 40× magnification. H) Immunofluorescent double-labeling was performed in frozen tissue sections from normal and HEx treated fallopian tube using monoclonal antibodies specific for Ki67 (green)/CK8 (red) and ki67(green)/CD31(red). Hoechst 3342 staining was performed to display all cell nuclei. I) Merged channels showing Immuno-fluorescent staining of the mouse FT- tissue sections shows an increase in the IL-6 (DAPI-blue/IL-6-red) and pSTAT3 (DAPI-blue/pSTAT3-red) expressions in mice injected with FT- cells co-cultured with HEx when compared to the control tissue.

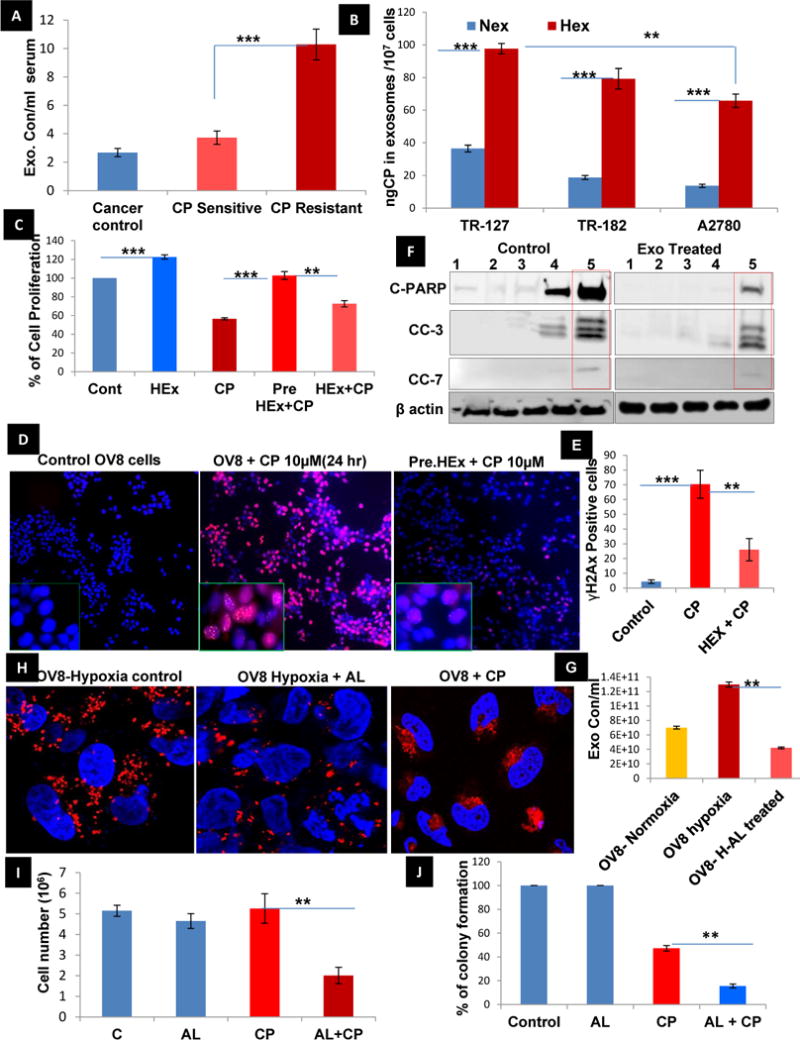

Effect of HEx on chemoresistance in ovarian cancer cells

A significant increase in serum exosome concentration but not in the size after cisplatin treatment was observed in cisplatin resistant ovarian cancer patients when compared with those patients who were cisplatin sensitive and in patients prior to treatment with cisplatin (Sup. Video 1–3, Fig.6A, Sup. Fig. 12A&B). This might as well address a new area of exosomal involvement in drug resistance. We then addressed whether the hypoxia impacts the exosomal efflux of cisplatin from ovarian cancer cells. A 5-fold higher concentration of cisplatin content in HEx vs NEx isolated per million cells in TR127, TR182 and A2780 cells was noted, as measured by ICP-MS (Fig. 6B). We then analyzed whether HEx co-cultured with ovarian cancer cells could induce resistance to cisplatin treatment. SRB assay indicated that pre-treatment of the ovarian cancer cells with HEx increased the resistance to cisplatin treatment with increased cell survival rate when compared to the control OVCAR-8 cells without the HEx treatment group (Fig. 6C,Sup. Fig.12C). This effect of HEx on cisplatin treatment in OVCAR-8 cells was further confirmed by the significant reduction in the ɣH2Ax positive cells and the apoptotic proteins expression by western blot analysis (Fig. 6D, E&F). When OVCAR-8 cells were treated with amiloride, a known exosomal inhibitor, decreased exosomal release was noted by NTA (Fig. 6G). Confocal microscopy further confirmed a finding indicative of the absence of secretory lysosomal phenotype showing perinuclear localization (Fig. 6H). In addition, we have confirmed the significant inhibition of cell growth and colony formation in amiloride pre-treatment and co-treatment with cisplatin. (Fig. 6I&J, Sup. Fig. 13A&B). This may prove effective in combating the chemoresistance mediated by exosomal efflux of cisplatin for which further studies are warranted both in-vitro and in-vivo. Overall these results suggest that hypoxia-induced cancer exosomes contribute to chemoresistance by a drug-efflux mechanism.

Fig.6. HEx involved in chemo-resistance.

A) Quantification of serum exosome concentration in ovarian cancer (before cisplatin treatment), cisplatin sensitive and resistant patient (after Cisplatin treatment) samples (n=5±SD, **p<0.005) show increased exosomal concentration/ml of serum. B) The measurement of cisplatin concentration in exosomes after treatment with cisplatin for 24 hr using ICP-MS in different ovarian cancer cell lines cultured in normoxia and hypoxia shows a significant efflux of the platinum via exosomes in hypoxia than normoxia (n=8±SD) (**p<0.005, ***p<0.0001using student t-test). C) The percentage of cell proliferation determined by sulphorhodamine assay was found to be significantly increased by co-culturing the OVCAR-8 cells with Hex (20μg) when compared to the control group (n=8±SD) (p<0.005 using student t-test). D, E) The OVCAR8 cells without any exosome treatment show an increase in ɣH2Ax positive cells on treatment with cisplatin at 10 μM for 24 hr when compared to the HEx pre-treated OVCAR-8 cells and was quantified based on the number of ɣH2ax positive cells (n=3±SD; **p<0.005, ***p<0.0001). F) A reduction in cisplatin sensitivity, despite STAT3 inhibition by HO-3867 treatment for 3hrs prior to cisplatin treatment, was observed by via reduced apoptotic protein expression of cleaved PARP and caspases 3&7 in HEx treated OVCAR-8 cells, when compared the OVCAR-8 cells without any prior exosome treatment, Lane: 1 (Control), Lane:2 (DMSO), Lane:3 (HO3867-10μM, STAT3 inhibitor), Lane: 4 (Cisplatin-10μM), Lane: 5 (HO3867+CP). G) The exosome concentration under hypoxia in OVCAR-8 cells quantified by NTA showed a significant decrease upon treatment with 100 μM amiloride (n=3±SD; **p<0.005). H) The treatment of OVCAR-8 cells in hypoxia with a known exosome inhibitor, amiloride, reduced the peripheral localization of the lysosomes labelled with lyso-tracker red dye when compared to cisplatin treatment where more peripherally oriented lyosomes were observed as captured by Confocal microscopy. I, J) The cell survival and colony formation assay using OVCAR-8 cells shows that amiloride (100 μM), when treated alone, is not cytotoxic when compared to control, but when co-treated with cisplatin (10 μM) did increase in the cytotoxic effects in 24 hr as compared with cisplatin treatment alone (n=3±SD; **p<0.005).

Discussion

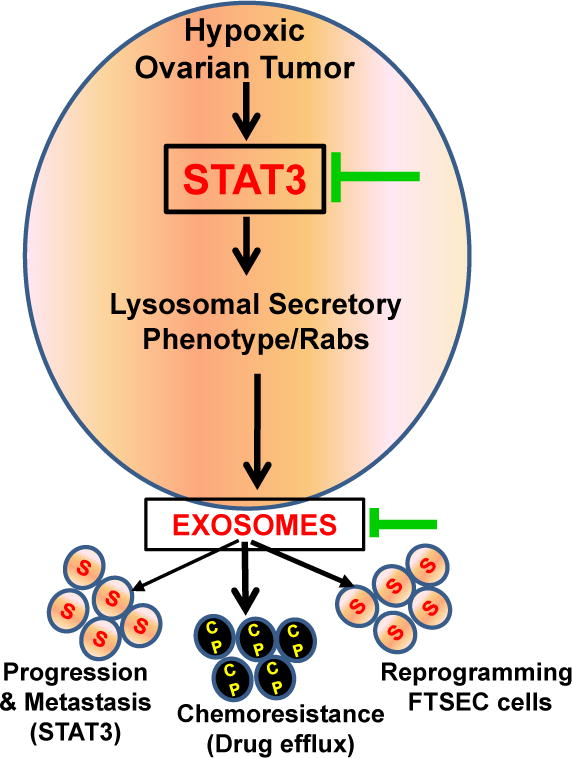

In this study we examined the role of hypoxia, and the regulation of Rab proteins by STAT3, in the release of exosomes in ovarian cancer. We have shown that altered lysosomal phenotype in multiple ovarian cancer cell lines and patient-derived ascites under hypoxic conditions favors increased exosome release by reduced endolysosomal fusion that was confirmed by increased Bhexosaminidase-A activity and increased real time expression of transcription factor EB (TFEB) that favors the lysosome docking under hypoxia in ovarian cancer cells. We have also demonstrated that STAT3, when induced under hypoxic conditions, regulates Rab7 and Rab27a proteins so as to promote exosome release in ovarian cancer cells, in conjunction with an altered lysosomal phenotype. Exosome-mediated transfer of oncogenic proteins was capable promoting tumor progression and metastasis in an orthotopic mouse tumor model and was also capable of reprograming the FT cells to increase expression of proteins associated with inflammation, cell proliferation and tumor progression in the mouse fallopian tube. Moreover, hypoxia-induced changes in exosome secretion may play a role in chemoresistance, as cisplatin efflux via exosomes was increased in ovarian cancer cells co-cultured with hypoxic-derived exosomes (Fig.7).

Fig. 7.

Schematic overview in hypoxic ovarian cancer cells representing STAT3 mediated signaling cascade of exosome release, contributing metastasis and chemo resistance and as well showing promising options for therapeutic interventions (Green arrow) with standard chemotherapy.

The mechanisms of exosomal release by the tumor cells and its contribution to tumor metastasis and drug resistance likely play an important role in cancer biology22, 23, 24, 25, 26. Changes in the lysosomal phenotype observed in hypoxic conditions might be the reason for peripheral shift of secretory or exocytic lysosomes outward, to the plasma membrane18, 19. We also found that this might be due to down-regulation of NEU1 that led to the accumulation of over-sialylated LAMP1 that favors the movement of lysosomes toward the plasma membrane to release their contents, which confirms NEU1 as a negative regulator of lysosomes exocytosis27. In addition, increased activity of secretory Rab proteins in the exocytic endosomal pathway favored the release of exosomes. Hypoxic ovarian cancer cells release more exosomes through enhancing the secretory pathway of the formed MVBs by Rab GTPases. Previous reports have shown that expression of Rab family proteins determines the aggressiveness of ovarian and breast cancer and leads to resistance to platinum based chemotherapy22. However, there is no clear evidence as to which Rab proteins are specifically involved in the vesicle trafficking in ovarian cancer. As observed in our study, Rab5 and Rab15 have opposing effects. This suggests that Rab5 favors the early stages in the formation of endosomes and reduced Rab15 indicates a decrease in recycling of endosomes. We confirmed that the real time expression of Rab7, a mediator of lysosomal endocytic degradation, was down-regulated and Rab27a, a regulator of vesicle exocytosis, was upregulated16, 28. We then investigated the role of STAT3 in this pathway given findings from a previous study which showed that overexpression of STAT3 increased lysosomal-mediated cell death during the physiological process of mammary gland involution29. However, we have previously shown that in the pathologic condition of ovarian cancer, cell death is evaded by high expression of STAT3 under hypoxic conditions3, 21. Our current study suggests that high expression of STAT3 might have a different impact on the lysosomal phenotype which is an important feature indicating the exosome release enhanced by alteration in the Rab-GTPases in hypoxic ovarian tumor.

Given the hypoxic microenvironment of ascites in ovarian cancer, exosomes released from tumor cells in ascites carry oncogenic proteins that can alter the signaling pathways in the surrounding recipient tumor cells or normal cells, favoring tumor progression and metastasis24, 30, 31, 32. We have shown that activated STAT3, FAS, and other oncogenic proteins were detected in HEx and patient-derived ascites. There is emerging evidence that cancer-derived exosomes may also contribute to the recruitment and reprogramming of the tumor microenvironment to form a pro-tumorigenic niche33, 34. Here, we observed that HEx has a similar effect on immortalized fallopian tube secretor epithelial cells (FT) in vivo. Recent studies have demonstrated that cancer exosomes are potential mediators of pre-metastatic niche formation, enhance VEGFR1 expression and angiogenesis in human renal cell carcinoma stem cells35, 36. Others have also suggested that vesicles in ascites may serve as stores of active proteinases that may aid in the metastatic process37, 38. Our study involving co-culture of HEx supports the hypothesis that epithelial tumor spread is also facilitated by the action of secreted exosomes and their reduction on the surrounding cells/tissues in the tumor microenvironment.

Further, HEx may play a significant role in resistance to anti-cancer therapy. Previous reports have shown that exosomes may be responsible for drug efflux and chemoresistance13, 19, 39; the current study confirms this finding and suggests that it is enhanced in the setting of hypoxia and as most of our results correlated with clinical samples, it is yet to be determined whether targeting these exosomal-mediated pathways can overcome platinum resistance in ovarian cancer. However, directly targeting Rab proteins or Rab-regulating proteins such as STAT3 using novel small molecule inhibitors may increase treatment success in combination with platinum-based drugs in hypoxia-mediated chemoresistant ovarian cancer.

Materials & Methods

Cell lines used in the current study

Immortalized ovarian surface epithelial cells IOSE (385 and 386), human fallopian tube secretory epithelial cells (FT) (Gifted from Dr. Ronny Drapkin, University of Pennsylvania, US), were used along with two immortalized high grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) human cell lines: OVCAR-8, A2780. The TR127 & TR182 cell lines, kindly gifted by Dr. G. Mor of Yale University, was derived from recurrent, chemotherapy resistant ovarian cancer. In addition ascites derived primary ovarian cancer cell (POCC’s) isolated from different ovarian cancer patients were cultured as explained in supplementary method section. The primary reason for using different cell lines was to prove that tumor progression and metastasis patterns vary widely in immortalized versus primary ovarian cancer cell lines isolated from patient ascites cell lines. We confirmed all the cell lines for mycoplasma activity using ATCC® Universal Mycoplasma Detection Kit, every 2 months. Once the frozen cells were thawed, they were passaged for 5 times only and discarded thereafter and a fresh vial was thawed.

Exosome isolation from culture medium, patient ascites and serum

To isolate tumor exosomes from culture media, the immortalized ovarian cancer cells were cultured for two days (48hr) in medium with exosome depleted FBS (Purchased from System Bioscience, CA, US). The conditioned medium was centrifuged at 400×g for ten minutes to remove whole cells and this supernatant was then centrifuged at 10,000×g for 30 minutes to remove large microvesicles and apoptotic vesicles and then the supernatants were filtered through 0.22 μm porous membranes followed by a spin at 100,000g for 1hr at 4°C to isolate the exosomes. Next, the exosomes pellet was washed in 10 ml 1× PBS followed by a second step of ultracentrifugation at 100,000g at 4°C for 1hr. The final pellet was re-suspended in PBS and the vesicular protein concentration was determined using the BCA protein assay from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The patients’ serum used in the current study was frozen samples and the ascites were obtained fresh from different patients undergoing surgery and were approved based on the Ohio State University IRB (Study number 2004C0124). Isolation and characterization of patient ascites cells as described previously40. For isolation of exosomes from 250 μl of cell-free serum and ascites, samples were thawed on ice 6. Samples were diluted in 11 ml 1× PBS and filtered through a 0.2 μm pore filter and then followed the same protocol as described above for the cell culture medium. The resulting exosome pellet was re-suspended in 100μl of cold PBS or lysis buffer according to the downstream applications such as NTA, TEM and Western blotting as we previously described41, 42.

Nano particle tracking analysis (NTA)

This technique is particularly powerful and sensitive for analyzing particles with a mean diameter of less than 100 nm- exosomes. For reliable NTA measurement, we used an appropriate exosome sample dilution that provides approximately 20–100 particles in the field of view. NTA post-acquisition settings were optimized and kept constant between samples, and each video was then analyzed to give the mean, mode, and median particle size together with an estimated number of particles per mL serum or per 107 cells. We recorded three 10 sec videos on the NanoSight LM10, which were analyzed using tracking software. The NTA software plots particle size range vs. particle number in the sample.43. 100 nm polystyrene latex microspheres were routinely analyzed to confirm instrument performance.

EXOCET Assay

This assay directly measures Acetyl-CoA Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity, known to be enriched within exosomes44, 45. The EXOCET exosome quantitation system is an enzymatic, colorimetric assay read at OD405. A standard curve that has been calibrated to isolated exosomes by NanoSight analysis is included in the kit, which enables the number of exosomes to be measured in our samples.

Cryo-Transmission electron microscopy (Cryo-TEM)

Cryo-TEM specimens of the exosome solutions were prepared using thin-film plunge freezing in a FEI Vitrobot (Mark IV). The vitrified specimens were mounted onto a Gatan 626.DH cryo-holder. Cryo-TEM observation was performed using low-dose mode on a FEI Tecnai F20 TEM according to a previously published protocol by Gao et.al., 201446.

Confocal microscopy

Confocal microscopy images were collected with a FluoView 1000 laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) using a 1.42 N.A., 60×, oil immersion objective.

Determination of cisplatin accumulation in cells and exosomes by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS)

Cisplatin accumulation/efflux by cells via exosomes was measured in different cell lines using OVCAR-8, TR127 and A2780 cells by ICP-MS analysis. Samples were analyzed on a Perkin Elmer Elan 6000 ICP-MS setup for a sample uptake of 0.1mL/min.194Pt, 195Pt and 196Pt using 115In as an internal standard (standardized at Trace Elements Lab., OSU). The samples were measured with eight replicates averaged and then the average concentration of the isotopes will be used as the final concentration for a single result per sample. Blanks were processed simultaneously with the samples to nullify the Pt contamination throughout the process.

STAT3 OE and knockdown experiments

For up and downregulation of STAT3 in OVCAR-8 cells, a lentiviral system (pGIPZ) from Santacruz Biotechnology with a set of different short hairpin RNAs (shRNA) was used. The resultant STAT3 knockdown cells were called as OVCAR-8 KD cells. A negative scrambled shRNA was used as a control41.

SRB assay

Cell proliferation rate in ovarian cancer cells treated with Hex and cisplatin was determined by a colorimetric assay using Sulforhodamine B (SRB), as described previously40, 47.

Protein Extraction and Digestion for LC-MS/MS

Exosome pellets were re-suspended in 100 μL (50 μL for normal cell controls) of 50 mM ABC containing 0.5% Rapigest (Waters Corp.), sonicated 2 × 10 sec. and incubated with shaking for 1 hour at RT and protein concentration were determined by Bradford assay. Further the samples were digested with trypsin and the peptide concentration was determined by nanodrop (A280nm).

Development of orthotopic tumor model

STAT3 overexpression OCC cells (3 × 10*6 cells in 100 μL of PBS) were injected into the ovarian bursa of 6-week-old BALB/c nude mice from the OSU Transgenic mice core lab. In vivo MRI imaging was done periodically to check upon the tumor growth. After sacrifice, the tumor weight and volume was measured. The animal protocol has been approved by OSU IACUC (Protocol number 2012A00000008-R1), we have followed vertebrate ethical regulations in this study.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean±1 standard deviation. To determine statistical significance among groups analysis of variance (ANOVA) was first performed. If ANOVA was statistically significant, the student’s t‐test was then performed to compare sub‐groups, p‐value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant. (Detailed Methods in Supplementary file)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Zhang Liwen, PhD, for proteomic analysis using Fusion Orbitrap instrument in OSU supported by NIH Award Number Grant S10 OD018056, Dr. Xiaokui Mo, Ph.D for analysis of Bioinformatics data and Dr. Min Gao, Ph.D, Kent University, for TEM analysis. Confocal images presented in this manuscript were generated using the services at the Campus Microscopy and Imaging Facility at OSU supported in part by grant P30 CA016058, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. We also would like to thankful to Dr. John Olesik, Trace Element Research lab at OSU who helped us to quantify the Cisplatin concentration in exosomes by ICP-Mass Spec. We are very thankful to Dr. John Hays for his willingness to pre-review this manuscript and provide valuable comments and suggestions. The authors are very thankful to Dr. Matthew Ringel, MD, and his lab member Dr. Moto Saji, for their invaluable help in exosome isolation protocols. The authors are also very thankful to Brentley Smith, GYN/ONC fellow OSU, Graduate students - Dongju Park and Christopher Koivisto, Medical student – Rashmi Madhukar and Undergraduate student - Riley Maria for the IHC, cell culture and basic assay help. This work was funded by Ovarian Cancer Research Fund (OCRF), NCI RO1-CA176078 grant (K.S. and D.E.C) and KOH ovarian cancer foundation grant to DKDP.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- BAF-1

Bafilomycin -A1

- CD63

Tetraspanin membrane protein of the intracellular vesicles

- dsDNA

double stranded DNA

- EpCAM

Epithelial cell adhesion molecule

- FAS

Fatty acid synthase

- FT

immortalized fallopian tube secretory epithelial cells

- GM-130

cis-golgi protein

- Hex

Exosomes isolated from cells cultured in hypoxia

- HIF-1α

Hypoxia inducible factor

- IOSE

Immortalized ovarian surface epithelial cells

- IPA

Ingenuity Pathway analysis

- LAMP1/2

Lysosome membrane associated proteins- 1 & 2

- MCOLN-1

Mucolipin-1

- miRs

micro RNAs

- MMP2&9

Matrix metalloproteinase2 &9

- NEU-1

Neuraminidase-1

- NEx

Exosomes isolated from cells cultured in normoxia

- POCC

primary ovarian cancer cells derived from patients

- Rab

Ras superfamily proteins with GTPase activity

- Spi2A

A class of serpins that act as inhibitors of lysosome proteases

- STAT3

Signal transducer and activator of transcription factor

- STAT3 KD

STAT3 knockdown cells

- STAT3 WT

STAT3 wild type cells

- TFEB

Transcription factor EB

- TSG101

Tumor susceptibility gene101

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors Contribution

KS, KDPD, & DEC. designed all experiments. KDPD and RW performed most of the in vitro and in vivo studies, exosome isolation, STAT3 knock down experiments, patient ascites cell characterization, cisplatin measurement and analyzed the data collected. JJW & RZ, collected patient ascites and performed WB. AAS performed the tumor histopathology. US performed the transfection work. KDPD, JJW, DEC and KS wrote, edited, and proofread the manuscript.

References

- 1.Finger EC, Giaccia AJ. Hypoxia, inflammation, and the tumor microenvironment in metastatic disease. Cancer metastasis reviews. 2010;29(2):285–293. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9224-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lengyel E. Ovarian cancer development and metastasis. The American journal of pathology. 2010;177(3):1053–1064. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selvendiran K, Bratasz A, Kuppusamy ML, Tazi MF, Rivera BK, Kuppusamy P. Hypoxia induces chemoresistance in ovarian cancer cells by activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(9):2198–2204. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Ovary Cancer. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmes D. Ovarian cancer: beyond resistance. Nature. 2015;527(7579):S217. doi: 10.1038/527S217a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kulbe H, Chakravarty P, Leinster DA, Charles KA, Kwong J, Thompson RG, et al. A dynamic inflammatory cytokine network in the human ovarian cancer microenvironment. Cancer research. 2012;72(1):66–75. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beach A, Zhang HG, Ratajczak MZ, Kakar SS. Exosomes: an overview of biogenesis, composition and role in ovarian cancer. Journal of ovarian research. 2014;7:14. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-7-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorayappan KDPWJ, Saini U, Bixel K, Riley M, Zingarelli R, Wanner R, Cohn D, Selvendiran K. Hypoxia-facilitated exosomal release from ovarian cancer cells is regulated by STAT3 and is associated with increased metastatic tumor burden. Gynecologic oncology. 2016;141(Supp 1):66. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azmi AS, Bao B, Sarkar FH. Exosomes in cancer development, metastasis, and drug resistance: a comprehensive review. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2013;32(3–4):623–642. doi: 10.1007/s10555-013-9441-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang HG, Grizzle WE. Exosomes: a novel pathway of local and distant intercellular communication that facilitates the growth and metastasis of neoplastic lesions. The American journal of pathology. 2014;184(1):28–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaksman O, Trope C, Davidson B, Reich R. Exosome-derived miRNAs and ovarian carcinoma progression. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35(9):2113–2120. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teng Y, Ren Y, Hu X, Mu J, Samykutty A, Zhuang X, et al. MVP-mediated exosomal sorting of miR-193a promotes colon cancer progression. Nature communications. 2017;8:14448. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Au Yeung CL, Co NN, Tsuruga T, Yeung TL, Kwan SY, Leung CS, et al. Exosomal transfer of stroma-derived miR21 confers paclitaxel resistance in ovarian cancer cells through targeting APAF1. Nature communications. 2016;7:11150. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Su SA, Xie Y, Fu Z, Wang Y, Wang JA, Xiang M. Emerging role of exosome-mediated intercellular communication in vascular remodeling. Oncotarget. 2017 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Zeng C, Zhan Y, Wang H, Jiang X, Li W. Aberrant low expression of p85 alpha in stromal fibroblasts promotes breast cancer cell metastasis through exosome-mediated paracrine Wnt10b. Oncogene. 2017 doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ostrowski M, Carmo NB, Krumeich S, Fanget I, Raposo G, Savina A, et al. Rab27a and Rab27b control different steps of the exosome secretion pathway. Nature cell biology. 2010;12(1):19–30. doi: 10.1038/ncb2000. sup pp 11-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirkegaard T, Jaattela M. Lysosomal involvement in cell death and cancer. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2009;1793(4):746–754. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kallunki T, Olsen OD, Jaattela M. Cancer-associated lysosomal changes: friends or foes? Oncogene. 2013;32(16):1995–2004. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safaei R, Larson BJ, Cheng TC, Gibson MA, Otani S, Naerdemann W, et al. Abnormal lysosomal trafficking and enhanced exosomal export of cisplatin in drug-resistant human ovarian carcinoma cells. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2005;4(10):1595–1604. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCann GA, Naidu S, Rath KS, Bid HK, Tierney BJ, Suarez A, et al. Targeting constitutively-activated STAT3 in hypoxic ovarian cancer, using a novel STAT3 inhibitor. Oncoscience. 2014;1(3):216–228. doi: 10.18632/oncoscience.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saini U, Naidu S, ElNaggar AC, Bid HK, Wallbillich JJ, Bixel K, et al. Elevated STAT3 expression in ovarian cancer ascites promotes invasion and metastasis: a potential therapeutic target. Oncogene. 2016 doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahlert C, Kalluri R. Exosomes in tumor microenvironment influence cancer progression and metastasis. Journal of molecular medicine. 2013;91(4):431–437. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1020-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalluri R. The biology and function of exosomes in cancer. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2016;126(4):1208–1215. doi: 10.1172/JCI81135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoshino A, Costa-Silva B, Shen TL, Rodrigues G, Hashimoto A, Tesic Mark M, et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature. 2015;527(7578):329–335. doi: 10.1038/nature15756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kucharzewska P, Christianson HC, Welch JE, Svensson KJ, Fredlund E, Ringner M, et al. Exosomes reflect the hypoxic status of glioma cells and mediate hypoxia-dependent activation of vascular cells during tumor development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(18):7312–7317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220998110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leca J, Martinez S, Lac S, Nigri J, Secq V, Rubis M, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast-derived annexin A6+ extracellular vesicles support pancreatic cancer aggressiveness. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2016;126(11):4140–4156. doi: 10.1172/JCI87734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yogalingam G, Bonten EJ, van de Vlekkert D, Hu H, Moshiach S, Connell SA, et al. Neuraminidase 1 is a negative regulator of lysosomal exocytosis. Developmental cell. 2008;15(1):74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vanlandingham PA, Ceresa BP. Rab7 regulates late endocytic trafficking downstream of multivesicular body biogenesis and cargo sequestration. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284(18):12110–12124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809277200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kreuzaler PA, Staniszewska AD, Li W, Omidvar N, Kedjouar B, Turkson J, et al. Stat3 controls lysosomal-mediated cell death in vivo. Nature cell biology. 2011;13(3):303–309. doi: 10.1038/ncb2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang T, Gilkes DM, Takano N, Xiang L, Luo W, Bishop CJ, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factors and RAB22A mediate formation of microvesicles that stimulate breast cancer invasion and metastasis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(31):E3234–3242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410041111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang B, Peng P, Chen S, Li L, Zhang M, Cao D, et al. Characterization and proteomic analysis of ovarian cancer-derived exosomes. Journal of proteomics. 2013;80:171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shender VO, Pavlyukov MS, Ziganshin RH, Arapidi GP, Kovalchuk SI, Anikanov NA, et al. Proteome-metabolome profiling of ovarian cancer ascites reveals novel components involved in intercellular communication. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2014;13(12):3558–3571. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.041194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sceneay J, Smyth MJ, Moller A. The pre-metastatic niche: finding common ground. Cancer metastasis reviews. 2013;32(3–4):449–464. doi: 10.1007/s10555-013-9420-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costa-Silva B, Aiello NM, Ocean AJ, Singh S, Zhang H, Thakur BK, et al. Pancreatic cancer exosomes initiate pre-metastatic niche formation in the liver. Nature cell biology. 2015;17(6):816–826. doi: 10.1038/ncb3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lobb RJ, Lima LG, Moller A. Exosomes: Key mediators of metastasis and pre-metastatic niche formation. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grange C, Tapparo M, Collino F, Vitillo L, Damasco C, Deregibus MC, et al. Microvesicles released from human renal cancer stem cells stimulate angiogenesis and formation of lung premetastatic niche. Cancer research. 2011;71(15):5346–5356. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graves LE, Ariztia EV, Navari JR, Matzel HJ, Stack MS, Fishman DA. Proinvasive properties of ovarian cancer ascites-derived membrane vesicles. Cancer research. 2004;64(19):7045–7049. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanlikilicer P, Rashed MH, Bayraktar R, Mitra R, Ivan C, Aslan B, et al. Ubiquitous Release of Exosomal Tumor Suppressor miR-6126 from Ovarian Cancer Cells. Cancer research. 2016;76(24):7194–7207. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Safaei R, Katano K, Larson BJ, Samimi G, Holzer AK, Naerdemann W, et al. Intracellular localization and trafficking of fluorescein-labeled cisplatin in human ovarian carcinoma cells. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2005;11(2 Pt 1):756–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saini U, Naidu S, ElNaggar AC, Bid HK, Wallbillich JJ, Bixel K, et al. Elevated STAT3 expression in ovarian cancer ascites promotes invasion and metastasis: a potential therapeutic target. Oncogene. 2017;36(2):168–181. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rath KS, Naidu SK, Lata P, Bid HK, Rivera BK, McCann GA, et al. HO-3867, a safe STAT3 inhibitor, is selectively cytotoxic to ovarian cancer. Cancer research. 2014;74(8):2316–2327. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chacko SM, Ahmed S, Selvendiran K, Kuppusamy ML, Khan M, Kuppusamy P. Hypoxic preconditioning induces the expression of prosurvival and proangiogenic markers in mesenchymal stem cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299(6):C1562–1570. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00221.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang W, Peng P, Kuang Y, Yang J, Cao D, You Y, et al. Characterization of exosomes derived from ovarian cancer cells and normal ovarian epithelial cells by nanoparticle tracking analysis. Tumour biology : the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2016;37(3):4213–4221. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Savina A, Vidal M, Colombo MI. The exosome pathway in K562 cells is regulated by Rab11. Journal of cell science. 2002;115(Pt 12):2505–2515. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.12.2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta S, Knowlton AA. HSP60 trafficking in adult cardiac myocytes: role of the exosomal pathway. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2007;292(6):H3052–3056. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01355.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao M, Kim YK, Zhang C, Borshch V, Zhou S, Park HS, et al. Direct observation of liquid crystals using cryo-TEM: specimen preparation and low-dose imaging. Microscopy research and technique. 2014;77(10):754–772. doi: 10.1002/jemt.22397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.ElNaggar AC, Saini U, Naidu S, Wanner R, Sudhakar M, Fowler J, et al. Anticancer potential of diarylidenyl piperidone derivatives, HO-4200 and H-4318, in cisplatin resistant primary ovarian cancer. Cancer biology & therapy. 2016;17(10):1107–1115. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2016.1210733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.