Abstract

Objective

Recently, a seemingly novel innate immune cell subset bearing features of natural killer and B cells was identified in mice. So-called NKB cells appear as first responders to infections, but whether this cell population is truly novel or is in fact a subpopulation of B cells and exists in higher primates remains unclear. The objective of this study was to identify NKB cells in primates and study the impact of HIV/SIV infections.

Design and Methods

NKB cells were quantified in both naïve and lentivirus infected rhesus macaques and humans by excluding lineage markers (CD3, CD127), and positive Boolean gating for CD20, NKG2A/C and/or NKp46. Additional phenotypic measures were conducted by RNA-probe and traditional flow cytometry.

Results

Circulating cytotoxic NKB cells were found at similar frequencies in humans and rhesus macaques (range, 0.01 to 0.2% of total lymphocytes). NKB cells were notably enriched in spleen (median, 0.4% of lymphocytes), but were otherwise systemically distributed in tonsil, lymph nodes, colon, and jejunum. Expression of immunoglobulins was highly variable, but heavily favoured IgM and IgA rather than IgG. Interestingly, NKB cell frequencies expanded in PBMC and colon during SIV infection, as did IgG expression, but were generally unaltered in HIV-infected human subjects.

Conclusion

These results suggest a cell type expressing both NK and B cell features exists in rhesus macaques and humans and are perturbed by HIV/SIV infection. The full functional niche remains unknown, but the unique phenotype and systemic distribution could make NKB cells unique targets for immunotherapeutics or vaccine strategies.

Keywords: innate immunity, B cell, NK cell, simian immunodeficiency virus, macaques

INTRODUCTION

Recent studies have demonstrated that in addition to traditional adaptive features, multiple subpopulations of B cells may also exhibit innate functions. However, thus far much of what we know about so-named innate-like B cells (ILB) comes from studies carried out in mice. In mice, ILB fall under the broad classification of B1 cells, which are predominantly present in the pleural and peritoneal cavities and also include marginal zone (MZ) B cells, and other related B cell phenotypes[1, 2]. Largely due to localization, ILB may be some of the first immune cells to come in contact with invading pathogens [2, 3]. ILB have highly cross-reactive BCRs and/or TLRs that results in robust cytokine production and/or enhanced production of natural antibodies against virus and bacterial antigens [4–6]. ILB have also been shown to have immunoregulatory properties through the production of IL-10 [7]. Although characterization of ILB has proven to be challenging in humans, several studies looking at B cells in the blood have identified multiple memory CD5+IgM+ B cell phenotypes that appear analogous to murine B1 cells [8–10]. Multiple studies have shown that phenotypic and functional B cell abnormalities, including induction of a regulatory B cell-like phenotype, are associated with HIV infection [11–15]. However any role for ILB in HIV disease is largely unexplored.

Most recently, a novel subset of ILB has been identified in both humans and mice to share features of natural killer (NK) and B cells, and is an early source of multiple innate cytokines including IL-18 and IL-12[16]. Natural killer-like B cells (NKB), like other ILB, also have semi-permanent expression of natural IgM, can activate NK and innate lymphoid cells following stimulation, and thus modulate a critical cascade of innate and adaptive immune responses eventually necessary to contain viral infections. However, Kerdiles et al. [17] questioned these findings and suggested that NKB in mice may not actually be a unique subset of B cell, but instead are just a subpopulation of conventional B cells. In rebuttal, Wang et al [18] reported mRNA expression of genes encoding NK1.1 (klrb1c) and NKp46 (Ncr1) in murine NKB cells. In order to help clarify the existence of the proposed NKB population in higher primates, we investigated whether the putative phenotype exists in blood and tissues of humans and rhesus macaques, and if chronic HIV and SIV infection may perturb this unique cell niche.

METHODS

Macaque and human samples

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and tissue mononuclear cells isolated from spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN), and colon of naïve rhesus macaques (n=18) were included in this study. PBMC and tissue mononuclear cells from spleen, colon, jejunum, MLN, oral lymph nodes (OLN), axillary lymph nodes (ALN), tonsils and jejunum from a chronically (140 days post challenge) SIVmac251-infected cohort (n=13) were also included. All animals were housed at Biomere (Worcester, MA, AAALC number 1152). All study samplings were reviewed and approved by the Biomere Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All animal housing and studies were carried out in accordance with recommendations detailed in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health with recommendations of the Weatherall report: “The use of non-human primates in research”. Animals were fed standard monkey chow diet supplemented daily with fruit and vegetables and water ad libitum. Social enrichment was delivered and overseen by veterinary staff and overall animal health was monitored daily. Animals showing significant signs of weight loss, disease or distress were evaluated clinically and then provided dietary supplementation, analgesics and/or therapeutics as necessary. Humane euthanasia was carried with an overdose of pentobarbital using standard protocols.

A total of 17 (PBMC and/or spleens) persons were analyzed in this study and the median ages were 46 years among naïve subjects and 39 years among untreated viremic HIV+ subjects. Both the University of Alabama at Birmingham and Harvard University IRB reviewed and gave approval for the studies herein and written informed consent was obtained from each of the study subjects. Frozen mononuclear cells from human naïve spleen samples were provided by Massachusetts General Hospital and approved by the local IRB.

Flow cytometric staining of mononuclear cells

Mononuclear cells were characterized using surface and intracellular markers to discriminate B cells, NK cells and NKB cells. Using polychromatic flow cytometry cross-reactive antibodies against the following antigens were included: IgA (goat polyclonal; Rockland Immunochemical), IgG (G18-145; BD Biosciences), IgM (G20-127; BD Biosciences), CD20 (2H7; BD Biosciences), CD40 (5C3; BD Biosciences), HLA-DR (IMMU-157; Beckman Coulter), NKG2A (Z199; Beckman Coulter), NKp46 (BAB281; Beckman Coulter), CD56 (HCD56; Biolegend); CD16 (3G8; BD Biosciences), CD127 (eBIORDR5; Life Technologies) and CD3 (SP34.2; BD Biosciences). Briefly, 1–2 X 106 cells were first stained with Aqua dye for 30 minutes at room temperature for live/dead separation. Cells were washed and stained for surface markers at 4°C for 30 minutes and then fixed using a 1% formaldehyde solution. Intracellular staining for granzyme B (GB11; BD Biosciences) was performed using Fix/Perm reagents (Caltag Laboratories) according to the manufacturer’s suggested protocol. Fixed samples were acquired on an LSRII (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (version 9.9.4; Treestar). Multiparametric analyses were performed using SPICE v.5.3[19].

After live lymphocyte gating, CD3−CD20+CD127− cells were gated as B cells, CD3−HLADR−NKG2A+ cells as NK cells, and CD3−CD20+CD127− NKG2A+cells as NKB cells in rhesus macaques; CD3−NKG2A−NKp46−CD20+ as B cells, CD3−NKG2A+/−NKp46+/−CD127− as NK cells and CD3−NKG2A+/−NKp46+/−CD20+CD127− cells as NKB cells in human samples. While samples were negatively gated for CD127 to exclude innate lymphoid cells,[20] inclusion of CD127 expression on NKB did not alter the immunological profile.

RNA-Flow

Mononuclear cells were thawed and rested for 12 hours in R10 media at 37°C prior to surface and intracellular staining. RNA-Flow hybridization was performed using the manufacturer’s recommended protocol (PrimeFlow, Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) with the antibodies detailed in the flow cytometry section, and with rhesus macaque-specific KLRC1 and KLRC2 probesets. Rhesus-specific probesets were custom designed with the assistance of Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) to target rhesus KLRC1 and KLRC2. Target probe sequences will be published elsewhere. Probesets were labeled with Alexa-488 (KLRC1) and Alexa-647 (KLRC2) fluorophores by Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA). All KLRC1 and KLRC2 gates were determined per sample by comparing the samples stained with all antibodies and probesets with samples only stained with antibodies (no probeset control).

Virus Quantification

Plasma HIV-1 RNA levels were determined using the Amplicor ultrasensitive HIV-1 monitor assay at UAB hospitals (version 1.5; Roche Diagnostics Systems) [21]. SIV plasma RNA was quantified as described previously[22].

Statistical analysis

Statistical differences between normal and HIV/SIV infected samples were analyzed by non-parametric Mann Whitney U test and were performed using GraphPad Prism v.7. Statistical differences between pies were calculated by Permutation test as described [19]. Differences between mean ranks were considered significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Lymphocytes expressing phenotypic features of both NK and B cells are found in rhesus macaques

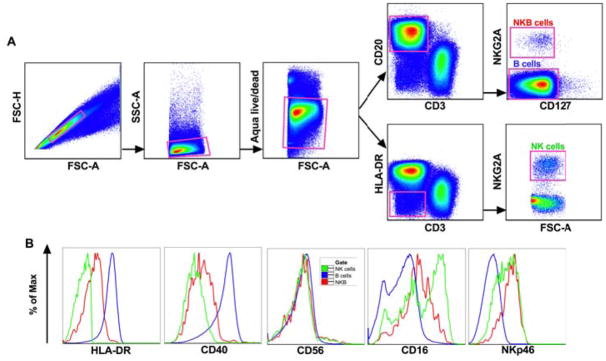

Based on the NKB cell phenotyping in mice described by Wang et al. [16], we identified NKB as CD3−CD20+NKG2A+ cells in rhesus macaques (Fig 1A) and further characterized these cells for their surface expression of other B cell and NK cell specific markers (Fig 1B). NKB cells showed intermediate to low expression of HLA-DR and CD40, which are typically highly expressed on B cells but not on NK cells. NKB cells also expressed levels of the activating NK cells receptor NKp46 similar to rhesus macaque NK cells, but levels of the Fc receptor CD16 were notably intermediate compared to B cells (which were negative above background), but lower than the high CD16 expression found on NK cells in blood[23]. NKB cells also expressed unexpectedly high levels of intracellular granzyme B (Supplementary Fig 1, http://links.lww.com/QAD/B277). Overall, this initial characterization suggested a cell type that uniquely overlapped phenotypically between B cells and NK cells.

Fig. 1. Phenotypic characterization of NKB cells in rhesus macaques.

Flow cytometric representations of (A) gating strategy used for identifying NKB, NK and B cell populations and (B) comparative expression of markers to delineate NKB cells from NK and B cell markers by histogram overlay analysis. Plots are representative of over 30 animals.

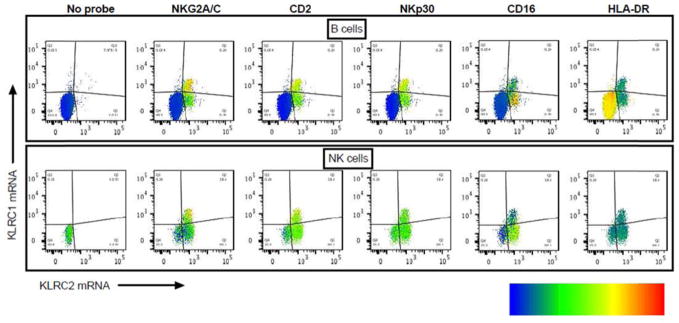

To further confirm NKB cells as unique subset of B cells and to rule out non-specific binding of NK specific antibodies to B cells, we analyzed transcript expression of the NK genes NKG2A (KLRC1 mRNA) and NKG2C (KLRC2 mRNA) in spleen samples using RNA-flow. A minor subpopulation of B cells corresponding to NKB cells expressed KLRC1 and KLRC2 mRNA at similar density compared to NK cells (Fig 2). In addition, these cells co-expressed NK cell specific surface proteins NKG2A/C, CD2, NKp30 and CD16 thus confirming the NKB cell population genuinely expressing NK cell markers.

Fig. 2. Expression of NK cell-specific transcripts and proteins on a subpopulation of B cells.

B cells (top row) and NK cells (bottom row) as identified in Fig. 1 were further gated for KLRC1 mRNA (NKG2A) and KLRC2 mRNA (NKG2C) using RNA-Flow. The left-most plots show B and NK cells that were stained in the absence of KLRC1 and KLRC2 probes (no probeset control, labeled “No probe”). The remaining plots correspond to representative samples showing KLRC1 vs. KLRC2 mRNA which are shown in each quadrant. Density and distribution of several NK cell-specific proteins (labeled as NKG2A, CD2, NKp30, CD16) as well as a non-NK cell protein (labeled HLA-DR) as measured by traditional flow cytometry are superimposed on these populations. The density of each indicated flow cytometry marker is illustrated by a heatmap from blue (low median expression) to red (high median expression). This sample is representative of 6 independent experiments.

NKB cells are found systemically, but expand in the gastrointestinal tract during SIV infection

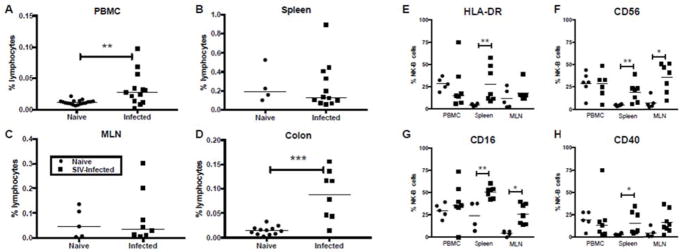

Wang et al. [16] describe NKB cells as unique innate cells that prime other innate and adaptive lymphocytes. Following identification in rhesus macaques, we next characterized the NKB cell population in multiple tissues of naïve and chronically SIV-infected macaques. The frequency of NKB cells varied significantly in normal tissues with a median of 0.012% in PBMC, a median of 0.047% in MLN, a median of 0.015% in colon, and a median of 0.191% in spleens (Fig 3). In SIV-infected macaques, NKB cells were significantly increased in PBMC and colon (Fig 3A & D), but not in MLN or spleen (Fig 3B & C). Although not specifically addressed between groups in this study, NKB cells were also found in OLN, ALN, tonsil and jejunum of SIV-infected animals (Supplementary Fig 2A, http://links.lww.com/QAD/B277) indicating their wide distribution. This particular cohort of SIV-infected macaques had a median viral load of 9.30 × 105 copies/ml, plasma (range, 4.17 × 104 to 4.05 × 107 copies), but there was no correlation between virus load and NKB frequencies. Further, the NKB cell phenotype was only partially modulated by SIV infection with significant upregulation of HLA-DR, CD16, CD40, and CD56 primarily restricted to spleen, but indicating a potential activation of these cells (Fig 3E–H).

Fig. 3. Elevated activated NKB cell frequencies in SIV-infected macaques.

Each data point represents percentages of NKB cells in (A) PBMC, (B) spleen, (C) mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) and (D) colon of naïve and chronically infected animals. Expression of NK and B cell specific markers (E) HLA-DR, (F) CD56, (G) CD16 and (H) CD40 are shown for naïve and SIV-infected macaques. Asterisks indicate significant differences between naïve and infected animals analyzed by Mann Whitney U test. * p<0.05, ** p<0.005, *** p<0.0005.

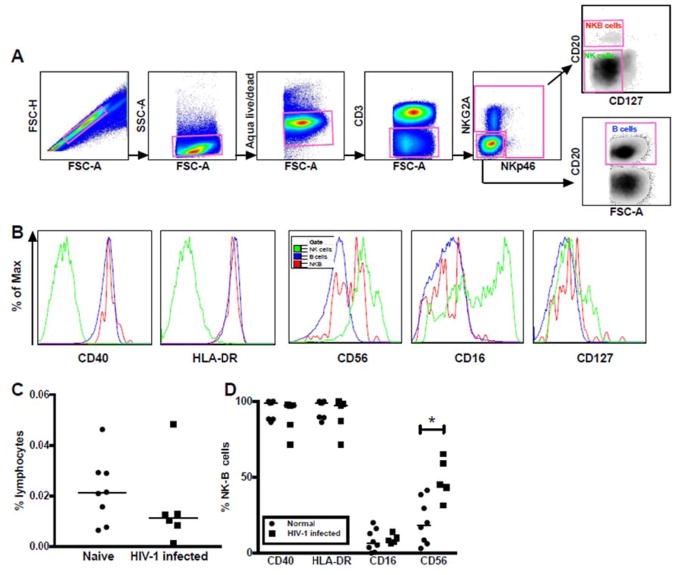

NKB cells are found in human tissues, but not peripherally expanded by HIV infection

To accommodate modest differences in phenotypic marker expression between human and macaque NK cells, we modified our gating strategy for human PBMC samples to identify NKB cells as CD3−NKG2A+/−NKp46+/−CD20+CD127− (Fig 4A). Otherwise, the NKB cell subset showed remarkable similarity to the rhesus macaque subpopulation with overlapping expression profiles for B cell and NK cell specific markers (Fig 4B), though more strikingly than in rhesus macaques (Fig 1B) human NKB cells expressed CD40 and HLA-DR at levels comparable to B cells (Fig. 4B). The range of NKB cell frequencies in human PBMC and spleen were similar to what was observed in rhesus macaques (medians 0.012% and 0.011% of lymphocytes, respectively) (Fig 4C, Supplementary Fig 2B, http://links.lww.com/QAD/B277). However, no significant differences in NKB frequencies were found between normal and HIV-infected/ART naïve subjects (median viral load of 4.89 × 10^4 copies/ml, plasma; range, 2.30 × 104 to 3.41 × 105 copies/ml, plasma). The phenotypic profiles of human NKB cells were generally retained, but similar to what was observed in some rhesus macaque tissues there was an upregulation of CD56 (Fig 4D).

Fig. 4. NKB cells in human PBMC.

(A) Representative gating strategy for delineating NKB populations in human PBMC, and (B) comparative expression of markers to delineate NKB B cells from NK and B cell markers by histogram overlay analysis. (C) Comparison of frequencies of NKB cells in normal and HIV infected/ART naïve patients. Expression of NK and B cell specific markers on NKB cells from both cohorts are shown in (D). Asterisks indicate significant differences analyzed by Mann Whitney U test. * p<0.05, ** p<0.005, *** p<0.0005.

Surface immunoglobulin expression on NKB

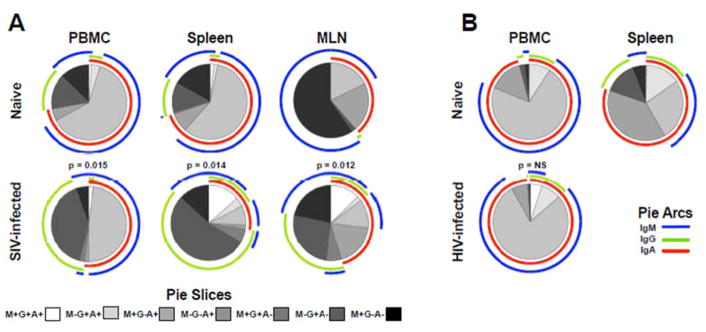

As a more robust indicator to determine NKB cell similarities to true B cells we next investigated the breadth of surface Ig expression in both normal and SIV-infected macaques and naïve and HIV-1-infected humans. Notably, the proportion of NKB expressing any type of Ig was highly variable and appeared to be more stable in humans (3% to 87% in rhesus macaques, 59% to 99% in humans). However, the diversity of expression on positive cells revealed unique patterns (Fig 5). Surface IgA and IgM were almost universally expressed in PBMC, spleen and MLN of both species (up to 99% in humans), and these findings are very similar to the initial description of stable IgM on murine NKB cells and other ILB [16, 24]. IgG was expressed at much lower levels in normal subjects, but increased up to 10-fold in spleen and MLN of SIV-infected macaques. In contrast IgG upregulation was not observed in PBMC of HIV-infected persons.

Fig. 5. Immunoglobulin expression on NKB cells in rhesus macaques and humans.

Distribution frequencies of IgA, IgG, and IgM calculated using Boolean gates of Ig positive samples averaged over 4 to 18 animals/human subjects per group, depending on tissue, using SPICE (v.5.3). Shaded pie slices indicate individual populations and pie arcs show overlapping expression of Ig molecules. Statistical evaluations were made between normal and infected samples and p values as determined by Permutations test are shown. NS, not significant.

DISCUSSION

Multiple lines of evidence suggest HIV and SIV infection may dysregulate B cell and NK cell functions [11–14, 23, 25–27]. Conversely, mobilization of anti-HIV/SIV antibodies is considered at the forefront of effective vaccination, alternative antivirals, and curative therapeutics against these diseases. However, very little is known about ILB populations that stably express Ig molecules and rapidly secrete innate cytokines, and how they may play into the dynamics of HIV transmission, disease progression, and treatment and preventative strategies. Herein, we present several seminal findings: (1) identification of a cellular phenotype in multiple macaque and human tissues bearing verifiable features of both B cells and NK cells; (2) expansion of putative NKB cells in the mucosae of chronically SIV-infected macaques; and (3) a lentivirus-driven shift in immunoglobulin expression on NKB cells.

Whether NKB cells truly represent a stable independent cell has been heavily debated. Although multiple future studies will be required to scrutinize this cell type, we do present several findings that support its existence. Phenotypically, CD3−CD20+ cells expressing NK cell-specific markers were found in multiple tissues of two different primate species. These findings could possibly be explained by membrane exchange or nonspecific antibody binding. However, our demonstration of NKG2A/C transcripts in these cells makes that extremely unlikely. Beyond that it remains unclear whether NKB cells are more closely related to B cells or NK cells. The diverse and high-level expression of multiple Ig molecules, as well as CD40 and HLA-DR, suggest NKB cells are more like B cells, but the intermediate levels of granzyme B could suggest these cells may also have cytolytic properties.

One of the most striking findings in this study was an overall expansion of NKB in circulation and in the colon during chronic SIV infection. Scientifically this may not be surprising given the high level of virus replication and cell death in the gastrointestinal tract, coupled with the putative role of NKB cells as rapid responders to infectious pathogens. The expansion did not however, correlate with virus loads, and no expansion was observed in the circulation of HIV-1-infected subjects. This could be attributed, at least in part, to species differences, the fact that human colorectal samples could not be analyzed in this cohort where the expansion was more striking, or that NKB are most sensitive to sites of very high inflammation. It is also likely that the large differences in viral loads between SIV-infected macaques and HIV-infected humans in this study (> 1 log) contributed to this distinction. SIV set points are traditionally much greater than in HIV-infected humans[28] and this study was not powered to address these types of differences. Another unique finding was the virus-induced alteration in Ig expression. It is tempting to speculate that the stable innate IgM and IgM expression shifting to IgG may reflect NKB cell plasticity and a novel switch from innate to adaptive immunity. Interestingly though IgG upregulation was significant in macaques but not in humans. Again since the increase was most prominent in tissues (which were not available from HIV-infected persons), this may not fully reflect the state of the cells in infection, but could also be a species or virus difference.

We acknowledge that the findings and theoretical niche of NKB cells remain controversial, but we present our findings, as they are to help further the resolution of this unexpected finding. Our data suggest that the NKB cell phenotype, regardless of unknown ontogeny is likely a real one. However, much as was previously suggested [17], we speculate NKB cells are a subpopulation of B cells that unexpectedly shares some properties overlapping with NK cells, the functional reasons for which remain unclear. Strikingly these cells are also significantly perturbed during lentivirus infection. Future studies will be needed to address the mechanism behind these phenomena in tissues of humans and macaques in both early and late infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the CVVR flow cytometry core and Michelle Lifton for expert technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants P01 AI120756, R01 DE026014, R01 DE026327, R01 AI20828 (all to RKR), and the Harvard Center for AIDS Research grant P30 AI060354.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Role of each of the authors in the study: R.K.R. designed the study and acquired funding. C.M., C.N., and S.V.S. performed most of the flow cytometric assays and associated analyses. D.R.R. performed the RNA-flow assays. S.S., R.J., B.H., K.K., and V.V. acquired and processed all samples. P.G. and S.J. provided clinical patient samples, clinical data and interpretation. R.K.R., C.N., and C.M. wrote the paper with assistance from all co-authors.

References

- 1.Baumgarth N. Innate-like B cells and their rules of engagement. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;785:57–66. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-6217-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cerutti A, Cols M, Puga I. Marginal zone B cells: virtues of innate-like antibody-producing lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(2):118–132. doi: 10.1038/nri3383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mebius RE, Kraal G. Structure and function of the spleen. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(8):606–616. doi: 10.1038/nri1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin F, Oliver AM, Kearney JF. Marginal zone and B1 B cells unite in the early response against T-independent blood-borne particulate antigens. Immunity. 2001;14(5):617–629. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Treml LS, Carlesso G, Hoek KL, Stadanlick JE, Kambayashi T, Bram RJ, et al. TLR stimulation modifies BLyS receptor expression in follicular and marginal zone B cells. J Immunol. 2007;178(12):7531–7539. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ochsenbein AF, Fehr T, Lutz C, Suter M, Brombacher F, Hengartner H, et al. Control of early viral and bacterial distribution and disease by natural antibodies. Science. 1999;286(5447):2156–2159. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5447.2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geherin SA, Gomez D, Glabman RA, Ruthel G, Hamann A, Debes GF. IL-10+ Innate-like B Cells Are Part of the Skin Immune System and Require alpha4beta1 Integrin To Migrate between the Peritoneum and Inflamed Skin. J Immunol. 2016;196(6):2514–2525. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casali P, Burastero SE, Nakamura M, Inghirami G, Notkins AL. Human lymphocytes making rheumatoid factor and antibody to ssDNA belong to Leu-1+ B-cell subset. Science. 1987;236(4797):77–81. doi: 10.1126/science.3105056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasaian MT, Ikematsu H, Casali P. Identification and analysis of a novel human surface CD5-B lymphocyte subset producing natural antibodies. J Immunol. 1992;148(9):2690–2702. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rakhmanov M, Keller B, Gutenberger S, Foerster C, Hoenig M, Driessen G, et al. Circulating CD21low B cells in common variable immunodeficiency resemble tissue homing, innate-like B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(32):13451–13456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901984106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Titanji K, Chiodi F, Bellocco R, Schepis D, Osorio L, Tassandin C, et al. Primary HIV-1 infection sets the stage for important B lymphocyte dysfunctions. AIDS. 2005;19(17):1947–1955. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000191231.54170.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Titanji K, De Milito A, Cagigi A, Thorstensson R, Grutzmeier S, Atlas A, et al. Loss of memory B cells impairs maintenance of long-term serologic memory during HIV-1 infection. Blood. 2006;108(5):1580–1587. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-013383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moir S, Fauci AS. Insights into B cells and HIV-specific B-cell responses in HIV-infected individuals. Immunol Rev. 2013;254(1):207–224. doi: 10.1111/imr.12067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrillo J, Negredo E, Puig J, Molinos-Albert LM, Rodriguez de la Concepcion ML, Curriu M, et al. Memory B cell dysregulation in HIV-1-infected individuals. AIDS. 2018;32(2):149–160. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez-Abente J, Prieto-Sanchez A, Munoz-Fernandez MA, Correa-Rocha R, Pion M. Human immunodeficiency virus type-1 induces a regulatory B cell-like phenotype in vitro. Cell Mol Immunol. 2017 doi: 10.1038/cmi.2017.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang S, Xia P, Chen Y, Huang G, Xiong Z, Liu J, et al. Natural Killer-like B Cells Prime Innate Lymphocytes against Microbial Infection. Immunity. 2016;45(1):131–144. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerdiles YM, Almeida FF, Thompson T, Chopin M, Vienne M, Bruhns P, et al. Natural-Killer-like B Cells Display the Phenotypic and Functional Characteristics of Conventional B Cells. Immunity. 2017;47(2):199–200. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang S, Xia P, Fan Z. Natural-Killer-like B Cells Function as a Separate Subset of Innate B Cells. Immunity. 2017;47(2):201–202. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roederer M, Nozzi JL, Nason MC. SPICE: Exploration and analysis of post-cytometric complex multivariate datasets. Cytometry A. 2011;79A(2):167–174. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.21015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah SV, Manickam C, Ram DR, Reeves RK. Innate Lymphoid Cells in HIV/SIV Infections. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1818. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H, Goepfert P, Reeves RK. Short Communication: Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells from HIV-1 Elite Controllers Maintain a Gut-Homing Phenotype Associated with Immune Activation. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30(12):1213–1215. doi: 10.1089/aid.2014.0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitney JB, Hill AL, Sanisetty S, Penaloza-MacMaster P, Liu J, Shetty M, et al. Rapid seeding of the viral reservoir prior to SIV viraemia in rhesus monkeys. Nature. 2014;512(7512):74–77. doi: 10.1038/nature13594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reeves RK, Gillis J, Wong FE, Yu Y, Connole M, Johnson RP. CD16-natural killer cells: enrichment in mucosal and secondary lymphoid tissues and altered function during chronic SIV infection. Blood. 2010;115(22):4439–4446. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-265595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baumgarth N. B-1 Cell Heterogeneity and the Regulation of Natural and Antigen-Induced IgM Production. Front Immunol. 2016;7:324. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zulu MZ, Naidoo KK, Mncube Z, Jaggernath M, Goulder PJR, Ndung’u T, et al. Reduced Expression of Siglec-7, NKG2A, and CD57 on Terminally Differentiated CD56(−)CD16(+) Natural Killer Cell Subset Is Associated with Natural Killer Cell Dysfunction in Chronic HIV-1 Clade C Infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2017;33(12):1205–1213. doi: 10.1089/AID.2017.0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mikulak J, Oriolo F, Zaghi E, Di Vito C, Mavilio D. Natural killer cells in HIV-1 infection and therapy. AIDS. 2017;31(17):2317–2330. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Demberg T, Brocca-Cofano E, Xiao P, Venzon D, Vargas-Inchaustegui D, Lee EM, et al. Dynamics of memory B-cell populations in blood, lymph nodes, and bone marrow during antiretroviral therapy and envelope boosting in simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac251-infected rhesus macaques. J Virol. 2012;86(23):12591–12604. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00298-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shedlock DJ, Silvestri G, Weiner DB. Monkeying around with HIV vaccines: using rhesus macaques to define ‘gatekeepers’ for clinical trials. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(10):717–728. doi: 10.1038/nri2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.