Abstract

Background

Little is known about the natural history of Mycoplasma genitalium (MG) infection. We retrospectively tested archived samples and assessed MG prevalence, incidence, persistence, recurrence and antimicrobial resistance markers among women participating in the Preventing Vaginal Infections trial, a randomized trial of monthly presumptive treatment to reduce vaginal infections.

Methods

High-risk, nonpregnant, HIV-negative women aged 18–45 from Kenya and the US were randomized to receive metronidazole 750mg + miconazole 200mg intravaginal suppositories or placebo for 5 consecutive nights each month for 12 months. Cervicovaginal fluid specimens were tested for MG using Hologic nucleic acid amplification testing at enrollment and every other month thereafter. Specimens that were MG+ underwent additional testing for macrolide resistance mediating mutations (MRMM) by DNA sequencing.

Results

Of 221 women with available specimens, 25 (11.3%) had MG at enrollment. Among 196 women without MG at enrollment, there were 52 incident MG infections (incidence=33.4 per 100 person-years). Smoking was independently associated with incident MG infection (adjusted HR=3.02; 95% CI 1.32, 6.93), and age <25 years trended towards an association (adjusted HR=1.70; 95% CI 0.95, 3.06). Median time to clearance of incident MG infections was 1.5 months (interquartile range 1.4, 3.0). Of the 120 MG+ specimens, 16 specimens from 15 different women were MRMM+ (13.3%), with no difference by country.

Conclusions

M. genitalium infection is common among sexually active women in Kenya and the Southern US. Given associations between MG and adverse reproductive health outcomes, this high burden of M. genitalium in reproductive-aged women could contribute to substantial morbidity.

Keywords: Mycoplasma genitalium, natural history, women, macrolide resistance mediating mutations, antibiotic resistance, Africa

INTRODUCTION

Mycoplasma genitalium is a sexually transmitted, fastidious bacterium that colonizes the female genital tract [1–6]. There is increasing evidence that M. genitalium infection is associated with adverse reproductive health outcomes in women, including cervicitis, urethritis, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), infertility, ectopic pregnancy, adverse birth outcomes and HIV-1 acquisition [1, 7–9]. However, data are limited on the natural history of M. genitalium infection, particularly with respect to duration of infection (persistence) and recurrence. Natural history studies are critical to improving our understanding of the contribution of M. genitalium to adverse health outcomes in women and informing guidelines for screening and treatment.

In addition over the past several years, M. genitalium treatment has been complicated by to the poor efficacy of doxycycline eand increasing resistance to azithromycin in high-income countries. Azithromycin resistance in M. genitalium is mediated by macrolide-resistance mediating mutations (MRMM) in the 23S rRNA gene [10]. The majority of studies assessing M. genitalium macrolide resistance in women have been conducted in Europe and Australia [11–17], where circulating resistance greater than 50% has been reported in some settings. To date, only one published report has estimated macrolide-resistant M. genitalium in the US. Among women with M. genitalium from 7 sites across the US, MRMM prevalence was 51% [18]. In East Africa, the prevalence of macrolide-resistant M. genitalium is unknown. Using data and stored specimens from women who previously participated in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of monthly periodic presumptive treatment to reduce vaginal infections, we conducted a retrospective cohort study to assess the natural history of M. genitalium infection and estimate the frequency of macrolide-resistant M. genitalium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and procedures

The Preventing Vaginal Infections (PVI) trial was a double-blinded, randomized controlled trial that assessed the effect of monthly metronidazole 750mg + miconazole 200mg intravaginal suppositories versus matching placebo to reduce rates of bacterial vaginosis (BV) and vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) [#NCT01230814]. Detailed methods and results have been previously described [19]. Briefly, 234 high-risk women from three sites in Kenya and one in the United States were enrolled between May 2011 and August 2012. Eligible women were 18–45 years of age, HIV-1 uninfected, not pregnant or breastfeeding, sexually active, and had one or more vaginal infections at screening (BV, VVC, or Trichomonas vaginalis). All participants provided written informed consent, including a separate consent for the storage and future testing of biological specimens. The trial was approved by the human subjects research committees at Kenyatta National Hospital (Nairobi, Kenya), the University of Washington (Seattle, WA), and the University of Alabama at Birmingham (Birmingham, AL).

At enrollment, structured face-to-face interviews were conducted to collect data on demographic, clinical and behavioral characteristics. At monthly follow-up visits, a urine pregnancy test was performed and data were collected on sexual behaviors, intravaginal practices, contraceptive use, product use and genital tract symptoms (abnormal itching or discharge). Non-pregnant participants received a month’s supply of study product and free male condoms. In addition, during follow-up visits at months 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12, participants underwent a physical examination including pelvic speculum examination with collection of genital swabs for diagnosis of genital tract infections. If a participant missed an examination visit, a physical examination was performed at her next follow-up visit.

Laboratory methods

Cervicovaginal fluid was collected using the Hologic APTIMA Combo 2 system (Hologic Inc.; San Diego, CA) at enrollment and months 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12. Specimens collected at enrollment were tested for the presence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis. The remainder of the enrollment specimen and all follow-up specimens were stored at −80°C for future testing. At the completion of the study, stored specimens were tested for M. genitalium using a research-use only transcription mediated amplification (TMA) assay with reagents provided by Hologic as part of their ongoing research program. Specimens with a value >40,000 relative light units were considered positive [20]. Samples that were M. genitalium positive underwent DNA extraction using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). MRMM in region V of the M. genitalium 23S ribosomal RNA gene were detected by PyroMark (Qiagen) DNA sequencing of PCR amplicons [10, 21].

Vaginal Gram stained slides were evaluated for BV using the Nugent’s score [22]. Saline and KOH wet preparations were examined for the presence of motile trichomonads, clue cells, and yeast. Endocervical Gram stained slides were scanned at low power to identify polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) in three non-adjacent oil immersion fields. Cervicitis defined as ≥30 PMNs on Gram stain. Yeast culture was performed on Sabouraud’s agar with a germ tube test to identify presumptive Candida albicans.

Statistical analysis

The objectives of this analysis were to (1) estimate the prevalence, infection duration, and correlates of M. genitalium identified at enrollment; (2) assess the incidence, infection duration and correlates of M. genitalium during follow-up; (3) assess the frequency of M. genitalium recurrence; and (4) determine MRMM frequency among women who tested positive for M. genitalium at any point during the trial. Mycoplasma genitalium clearance was defined as testing negative after a previous positive result, and time of clearance was estimated as the mid-point between the last positive and first negative result. Recurrent M. genitalium infection required a previous positive result, with one or more interim negative results, followed by a new positive result. Time of recurrence was considered to be the visit at which recurrent M. genitalium was first detected. Strain typing was not performed, so it was not possible to determine whether recurrences represented infection with a new strain versus recurrence or reinfection with an identical strain.

The analysis population was restricted to participants who provided consent for future testing of stored specimens. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics and chi-squared and T-tests were performed as appropriate. Logistic regression models were used to assess correlates of prevalent M. genitalium infection at enrollment. Age and study site were included in multivariable models based on a priori assumptions. In a prior analysis, we observed a trend towards a lower incidence of M. genitalium in the intervention arm compared to placebo [23]; therefore, initial analyses assessing correlates of incident infection were adjusted for study arm and stratified by site. Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess baseline and time-varying correlates of incident M. genitalium infection. Factors associated with M. genitalium infection with a p-value <0.10 in bivariate analyses were considered for inclusion in multivariable models. Factors that continued to have a p-value <0.10 were retained in final multivariable models. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the proportion of successfully tested specimens with MRMM. All statistical tests were assessed using a 2-sided α of 0.05. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 14.1 (StataCorp, Inc., College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Of 234 women enrolled, 221 (94%) returned for follow-up and provided consent for future testing. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Median age was 29 years (interquartile range [IQR] 24–34), 24% of participants were from the US, and 54% reported ever having sex in exchange for money, goods or services. Overall, 77(35%) participants tested positive for M. genitalium either at enrollment or during follow-up. A higher proportion of participants from Kenya experienced M. genitalium infection at during study participation compared to those from the US (64/168[38%] versus 13/53[25%], respectively; p=0.07).

Table 1.

Correlates of prevalent M. genitalium infection at enrollment

| All participants N=221 |

M. genitalium detected n=25 |

M. genitalium not detected n=196 |

Univariate OR (95% CI) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and behaviors | ||||||||

| Age < 25 years | 62 | (28) | 9 | (36) | 53 | (27) | 1.52 | (0.63, 3.64) |

| Partnership status | ||||||||

| Married or living with a partner | 63 | (29) | 5 | (20) | 58 | (30) | 1.00 | — |

| Separated, divorced or widowed | 87 | (40) | 10 | (40) | 77 | (39) | 1.51 | (0.49, 4.65) |

| Never married | 71 | (32) | 10 | (40) | 61 | (31) | 1.90 | (0.61, 5.90) |

| Number of live births | 2 | (1–3) | 1 | (1–2) | 2 | (1–3) | 0.93 | (0.69, 1.27) |

| Family planning method | ||||||||

| No modern method | 39 | (18) | 5 | (20) | 38 | (20) | 1.00 | — |

| Condoms only | 61 | (28) | 9 | (36) | 52 | (27) | 1.32 | (0.40, 4.24) |

| Oral contraceptives | 23 | (10) | 2 | (8) | 21 | (11) | 0.72 | (0.13, 4.06) |

| Injectable contraceptives | 49 | (22) | 3 | (12) | 46 | (23) | 0.50 | (0.11, 2.11) |

| IUD | 14 | (6) | 2 | (8) | 12 | (6) | 1.27 | (0.22, 7.39) |

| Implant | 14 | (6) | 2 | (8) | 12 | (6) | 1.27 | (0.22, 7.39) |

| Tubal ligation | 15 | (7) | 2 | (8) | 15 | (8) | 1.01 | (0.18, 5.80) |

| Currently smoke cigarettes | 30 | (14) | 5 | (20) | 25 | (13) | 1.71 | (0.59, 4.97) |

| Vaginal washing in the past month | 111 | (50) | 13 | (52) | 98 | (50) | 1.08 | (0.47, 2.49) |

| Sex in exchange for goods/money/services | 119 | (54) | 17 | (68) | 102 | (52) | 1.96 | (0.81, 4.75) |

| Sexual behaviors in the past week | ||||||||

| Vaginal sex | ||||||||

| None | 41 | (19) | 3 | (12) | 38 | (19) | 1.00 | — |

| 1–2 acts | 89 | (40) | 10 | (40) | 79 | (40) | 1.60 | (0.41, 6.17) |

| 3–4 acts | 36 | (16) | 3 | (12) | 33 | (17) | 1.15 | (0.22, 6.10) |

| 5 or more | 55 | (25) | 9 | (36) | 46 | (23) | 2.48 | (0.63, 9.81) |

| Unprotected sex | ||||||||

| No sex | 41 | (19) | 3 | (12) | 38 | (19) | 1.00 | — |

| 100% condom use | 95 | (43) | 14 | (56) | 81 | (41) | 2.19 | (0.59, 8.07) |

| Intermittent condom use | 23 | (10) | 3 | (12) | 20 | (10) | 1.90 | (0.35, 10.29) |

| No condom use | 62 | (28) | 5 | (20) | 57 | (29) | 1.11 | (0.25, 4.93) |

| Number of sex partners | ||||||||

| None | 41 | (19) | 3 | (12) | 38 | (19) | 1.00 | — |

| 1 partner | 109 | (49) | 12 | (48) | 97 | (49) | 1.57 | (0.42, 5.87) |

| 2 or more partners | 71 | (32) | 10 | (40) | 61 | (31) | 2.08 | (0.54, 8.03) |

| New partner | 45 | (20) | 9 | (36) | 36 | (18) | 2.50 | (1.02, 6.11) |

| History of anal sex | 25 | (11) | 3 | (12) | 22 | (11) | 1.08 | (0.30, 3.90) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||||

| Gonorrhea | 3 | (1) | 0 | (0) | 3 | (2) | — | — |

| Chlamydia | 16 | (7) | 0 | (0) | 16 | (8) | — | — |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | 16 | (7) | 3 | (12) | 13 | (7) | 1.90 | (0.51, 7.19) |

| Vulvovaginal candidiasis | 52 | (24) | 10 | (40) | 42 | (21) | 2.44 | (1.02, 5.83) |

| BV by Nugent score | ||||||||

| 0–3 | 81 | (37) | 7 | (28) | 89 | (45) | 1.00 | — |

| 4–6 | 44 | (20) | 6 | (24) | 38 | (19) | 2.01 | (0.63, 6.37) |

| 7–10 | 96 | (44) | 12 | (48) | 69 | (35) | 2.21 | (0.83, 5.91) |

| Cervicitis1 | 32 | (15) | 4 | (16) | 28 | (14) | 1.14 | (0.36, 3.56) |

Cervicitis defined as ≥30 PMNs on Gram stain. Two results missing from M. genitalium negative women.

Prevalence, clearance and persistence

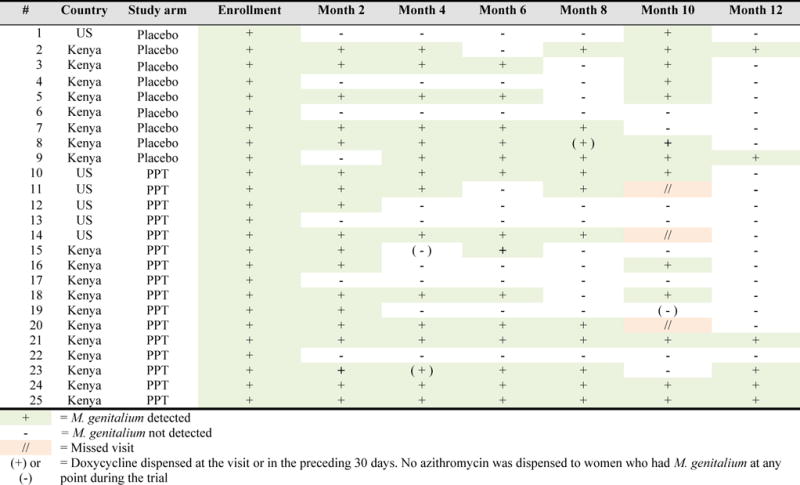

Mycoplasma genitalium prevalence at enrollment was 11.3% and did not differ between Kenyan (11.3%) and US participants (11.3%). Of note, the prevalence of M. genitalium was higher than other curable STIs (C. trachomatis = 7%; N. gonorrhoeae = 1%; T. vaginalis = 7%), and no M. genitalium co-infections with C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae were observed (Table 1). Associations between participant characteristics and prevalent M. genitalium are presented in Table 1. In unadjusted analysis, having a new sexual partner (odds ratio [OR]=2.50; 95% CI 1.02, 6.11) and having VVC (OR=2.44; 95% CI 1.02, 5.83) were associated with prevalent M. genitalium. In multivariable analyses that adjusted for age and study site, the effect estimate was similar for VVC (adjusted OR=2.45; 95% CI 1.00, 5.99) and attenuated slightly for having a new sexual partner (adjusted OR=2.38; 95% CI 0.87, 6.49). Condom use and the prevalence of cervicitis did not differ between women with prevalent M. genitalium infection versus those that were M. genitalium negative. Among 25 women with prevalent M. genitalium at enrollment, 22 participants cleared their M. genitalium infection prior to the end of the study, while 3 participants had M. genitalium detected at every study visit. Median time to clearance of prevalent infection was 3.9 months (interquartile range [IQR] 1.0, 8.4) [Figure 1]. Use of doxycycline was uncommon and did not appear to correlate with M. genitalium clearance (Figure 1). No azithromycin was dispensed to women with M. genitalium infection at any point in the trial.

Figure 1.

M. genitalium infection and resolution among participants with M. genitalium detected at enrollment

Incidence, clearance, persistence and recurrence

Among 196 women without M. genitalium at enrollment, there were 52 incident M. genitalium infections during 155.7 person years of follow-up (overall incidence M. genitalium [excluding recurrences]=33.4 per 100 person-years). Mycoplasma genitalium incidence was higher among Kenyan participants compared to US participants (38.4 per 100 person-years [95% CI 28.7, 51.4] versus 18.2 per 100 person-years [95% CI 8.7, 38.1]; p=0.06). In univariate analysis, being a current smoker was associated with incident infection, while younger age and concurrent BV trended towards an association (Table 2). In a multivariable model that included these three factors in addition to study arm and stratified by site, smoking was independently associated with increased risk of incident M. genitalium (adjusted HR=3.02; 95% CI 1.32, 6.93), while the effect estimates for concurrent BV (adjusted HR=1.59; 95% CI 0.87, 2.88) and age <25 years (adjusted HR = 1.70; 95% CI 0.95, 3.06) continued to trend towards an association.

Table 2.

Correlates of incident M. genitalium infection during follow-up

| Number of events | Person-years | Incidence | Bivariate HR (95% CI)1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline factors | |||||

| Age | |||||

| <25 years | 18 | 40.0 | 45.1 | 1.67 | (0.93, 2.98) |

| ≥ 25 years | 34 | 115.7 | 29.4 | 1.00 | – |

| Partnership status | |||||

| Married or living with a partner | 14 | 50.6 | 27.7 | 1.47 | (0.68, 3.19) |

| Separated, divorced or widowed | 21 | 61.0 | 34.4 | 1.42 | (0.61, 3.33) |

| Never married | 17 | 44.1 | 38.6 | 1.00 | – |

| Number of live births | |||||

| 2 or more live births | 34 | 85.7 | 39.7 | 1.17 | (0.42, 3.30) |

| 1 live birth | 13 | 46.3 | 28.1 | 0.97 | (0.32, 2.93) |

| None | 5 | 23.7 | 21.1 | 1.00 | – |

| Currently smoke cigarettes | |||||

| Yes | 9 | 16.6 | 54.1 | 3.14 | (1.42, 6.96) |

| No | 43 | 139.1 | 30.9 | 1.00 | – |

| Sex in exchange for goods/money/services | |||||

| Yes | 24 | 83.2 | 28.8 | 0.71 | (0.27, 1.86) |

| No | 28 | 72.5 | 38.6 | 1.00 | – |

| History of anal sex | |||||

| Yes | 2 | 19.1 | 10.5 | 0.38 | (0.09, 1.72) |

| No | 50 | 136.6 | 36.6 | 1.00 | – |

| HSV-2 status | |||||

| Positive | 33 | 95.6 | 34.5 | 1.21 | (0.68, 2.15) |

| Negative | 17 | 60.0 | 31.6 | 1.00 | – |

| Time-varying factor2 | |||||

| Vaginal sex | |||||

| 5 or more | 11 | 36.3 | 30.3 | 0.86 | (0.38, 1.98) |

| 3–4 acts | 5 | 24.8 | 20.2 | 0.41 | (0.15, 1.18) |

| 1–2 acts | 22 | 57.6 | 38.2 | 0.88 | (0.44, 1.77) |

| None | 14 | 37.1 | 37.7 | 1.00 | – |

| Unprotected sex | |||||

| 100% condom use | 21 | 66.1 | 31.8 | 0.82 | (0.41, 1.63) |

| Intermittent condom use | 5 | 14.4 | 34.6 | 1.03 | (0.37, 2.91) |

| No condom use | 12 | 37.8 | 31.8 | 0.62 | (0.27, 1.41) |

| No sex | 14 | 37.1 | 37.7 | 1.00 | – |

| Number of sex partners | |||||

| 2 or more partners | 11 | 40.6 | 27.1 | 0.75 | (0.32, 1.75) |

| 1 partner | 27 | 77.8 | 34.7 | 0.78 | (0.39, 1.54) |

| None | 14 | 37.2 | 37.6 | 1.00 | – |

| New partner | |||||

| Yes | 9 | 30.2 | 29.8 | 1.04 | (0.47, 2.32) |

| No | 43 | 125.5 | 34.3 | 1.00 | – |

| Vaginal washing in the past month | |||||

| Yes | 13 | 42.6 | 30.5 | 1.18 | (0.56, 2.48) |

| No | 39 | 113.1 | 34.5 | 1.00 | – |

| BV by Nugent score3 | |||||

| Yes | 19 | 40.3 | 47.1 | 1.71 | (0.96, 3.08) |

| No | 33 | 115.2 | 28.6 | 1.00 | – |

| BV by Nugent score at the preceding visit3 | |||||

| Yes | 13 | 41.5 | 31.3 | 0.95 | (0.50, 1.81) |

| No | 39 | 114.0 | 34.2 | 1.00 | – |

| Vulvovaginal candidiasis | |||||

| Yes | 4 | 18.0 | 22.2 | 0.68 | (0.24, 1.92) |

| No | 48 | 137.3 | 35.0 | 1.00 | – |

Univariate Cox proportional hazards models stratified by site and adjusted for study arm. Follow-up censored at time of first infection

Factors reported at the same visit as M. genitalium testing unless otherwise indicated.

Nugent score 7–10 vs. 0–6.

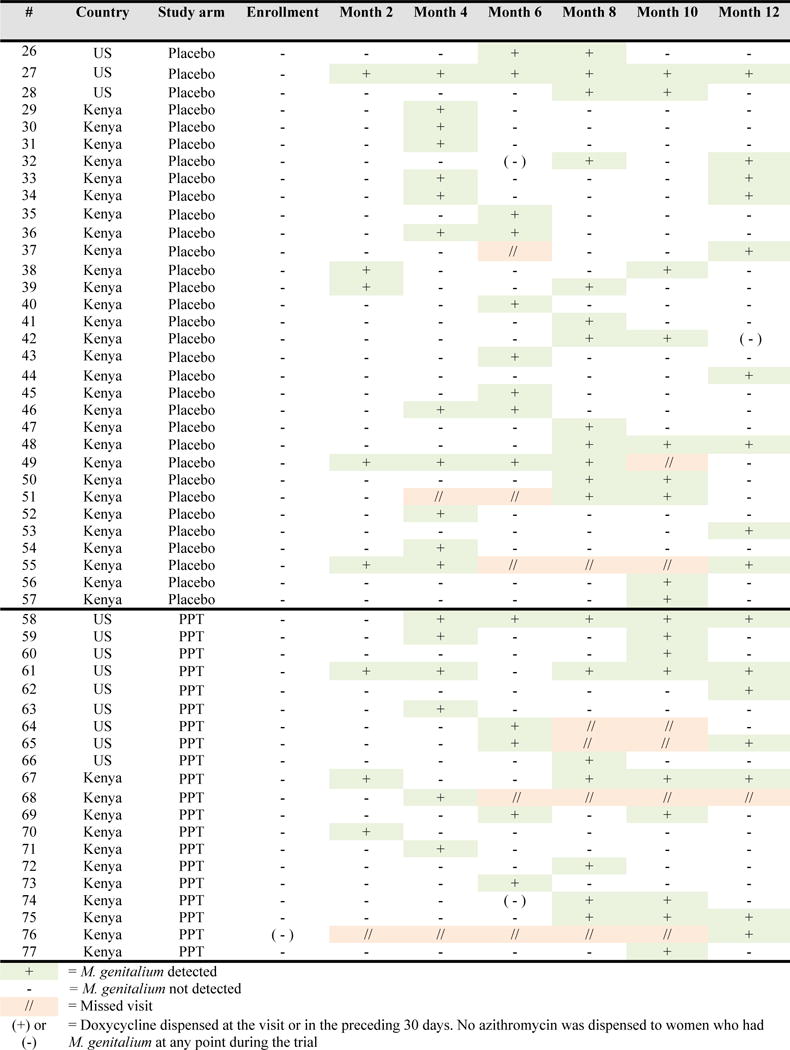

The duration and patterns of incident M. genitalium are presented in Figure 2. Median time to M. genitalium clearance was 1.5 months (IQR 1.4, 3.0) and did not differ by study arm (p=0.65). Of 52 women who experienced an incident infection during follow-up, 43 (83%) experienced one incident infection (i.e. no recurrence) and the majority had M. genitalium detected at only one study visit (26/43[60%]). Again, reported use of doxycycline was uncommon and did not appear to correlate with clearance of incident or recurrent infection (Figure 2). Of 61 participants who had either prevalent (n=22) or incident (n=39) M. genitalium and cleared their infection, 20(34%) had a recurrence of M. genitalium during study follow-up, with a median time to recurrence of 4.1 months (IQR 3.7, 7.3).

Figure 2.

Incident M. genitalium infection by study arm

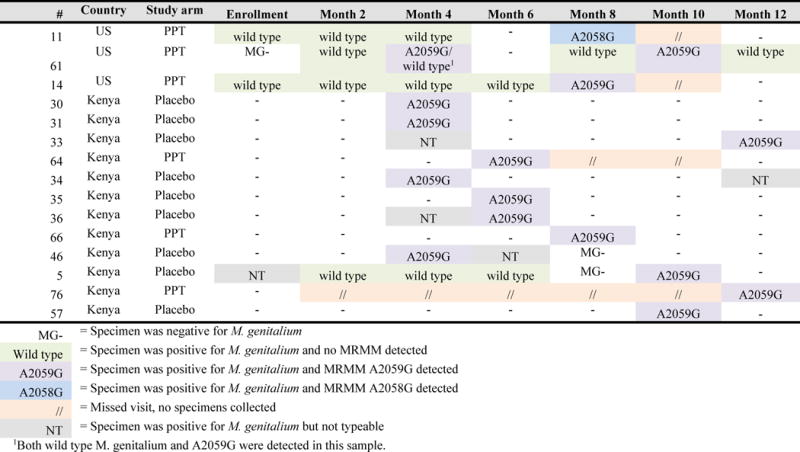

Macrolide resistance-mediating mutations

Among 77 women who tested positive for M. genitalium during the trial, specimens from 26 women were unevaluable for MRMM testing. Fifty-one women had a total of 120 evaluable M. genitalium samples that were tested for MRMM. Sixteen specimens (13.3%) from 15 different women tested positive for MRMM; mutations A2059G and A2058G were detected. The proportion of specimens with MRMM did not differ by country (Kenya: 12 of 82 [14.6%]; US: 4 of 38 [10.5%]; p=0.54). Patterns of M. genitalium infection among women with MRMM are displayed in Figure 3. Ten of 15 women with MRMM were M. genitalium negative at the prior visit, suggesting that macrolide resistant M. genitalium was acquired from a sex partner. In most cases of MRMM, infection was cleared by the next assessment. Mean duration of infection differed by MRMM status. Women with wild type M. genitalium infection had a longer median duration of infection (48 days; IQR 43, 106) compared to those with M. genitalium with MRMM (42 days; IQR 40, 44) [p=0.01].

Figure 3.

Patterns of M. genitalium infection and MRMM among women with MRMM at any point during participation in the PVI trial

DISCUSSION

In this prospective cohort of Kenyan and US women, we observed a high prevalence of M. genitalium infection (11.3%), which was detected more frequently than other curable STIs. We observed a similar prevalence of M. genitalium between Kenyan and US women, with an overall prevalence that was consistent with observations from studies of high-risk women in Uganda (14%) [24], Kenya (12.9%-16%) [25–27], South Africa (8.7%) [28] and the US (7.7%-19.2%) [18, 29, 30]. We also observed a high incidence of M. genitalium infection (33.4 per 100 person-years), which again, was substantially higher than the incidence of other curable STIs in this cohort reported previously (C. trachomatis incidence=11.7 per 100 person-years; N. gonorrhoeae incidence=7.2 per 100 person-years) [23]. Data on M. genitalium incidence are sparse, but our estimates are similar to those reported by other Kenyan studies (22.7–34.6 per 100 person year) [26, 27]. This high prevalence and incidence of M. genitalium highlights the significant burden of this pathogen among reproductive-aged women.

Differences were observed in factors associated with prevalent M. genitalium infection versus incident infection. Detection of VVC and having a new sex partner were associated with prevalent M. genitalium, but were not associated with incident infection. Conversely, being a current smoker was associated with increased risk of incident infection, while younger age and concurrent BV trended towards an association. For smoking, age and concurrent BV, no association was observed for prevalent M. genitalium. These differences may be due to the fact that risk factor assessment was performed most likely after M. genitalium infection occurred (i.e. prevalent infections could have been recent or persisted for months), whereas risk factor assessment for incident infections occurred closer to the time of actual infection. The association of smoking, age and concurrent BV with incident, but not prevalent infection is likely due to limited study power and the smaller number of prevalent infections at baseline. Of note, the effect estimates for the association of smoking, age and concurrent BV with prevalent MG were in the same direction as those in the incidence analysis and of generally similar magnitude. Our findings regarding BV and incident M. genitalium differed from a study by Lokken et al. that reported an association with BV at the preceding visit and incident infection. Both cohorts were from Kenya and had sampling every two months [27]. However, the inclusion of women receiving a vaginal health intervention as part of present study decreased the overall prevalence of BV and could have impacted the relationship between BV and M. genitalium susceptibility. Lastly, in contrast to other reports [5, 29, 31, 32], no association was observed between cervicitis by Gram stain and prevalent M. genitalium.

Among women with prevalent M. genitalium, median time to clearance was approximately 4 months. This represents the lower bound for infection duration among those with prevalent infection, since we were unable to account for person-time prior to enrollment. Median infection duration among women with incident M. genitalium was 1.5 months. This infection duration was similar to the median clearance time reported in a study of Ugandan women (2.1 months) [24], but slightly shorter than those observed in another cohort of Kenyan women (2.9 months) [27]. Overall, there was little reported use of azithromycin and doxycycline in our cohort, and no women who tested positive for M. genitalium during follow-up ever received azithromycin. In all cases where doxycycline was dispensed during the trial, it was either received at M. genitalium-negative time points or did not result in eradication of the organism in infected women, suggesting that the vast majority of infections were cleared spontaneously. Recurrent M. genitalium infection occurred in approximately one-third of women, which is also consistent with the recurrence rate among women in the Ugandan study (39%) [24].

The proportion of M. genitalium infections with MRMM was relatively low (13.3% of M. genitalium positive specimens had MRMM detected) compared to reports from other regions, where MRMM prevalence has approached 60% [15–18]. The frequency of MRMM in our study population was similar to that observed in a cohort of women in South Africa (MRMM prevalence=9.8%) [28]. Azithromycin-resistant infections emerge after azithromycin therapy in approximately 10% of M. genitalium positive individuals [33]. The lower frequency of MRMM observed in these African studies may be due to lower rates of background azithromycin use, reducing selective pressure. Despite the low overall frequency of MRMM detection, the majority of M. genitalium infections with MRMM were detected as incident infections, demonstrating that macrolide resistant M. genitalium is circulating in these regions. Interestingly, the duration of infection with macrolide resistant M. genitalium was shorter than wild type M. genitalium, which suggests that macrolide resistant M. genitalium may be less fit or more easily cleared than wild type strains. Given the rapid emergence of macrolide resistance [34], it is important to characterize the prevalence of MRMM in populations at high risk for M. genitalium infection to better inform treatment guidelines and potentially minimize treatment failure.

Our study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. Specimens for M. genitalium testing were collected every other month, which may have inflated estimates of infection duration and may have also resulted in failure to detect infections of short duration. More frequent, monthly sampling would improve the precision of infection duration estimates and incidence. A proportion of M. genitalium positive specimens were unevaluable for MRMM testing, limiting our ability to assess MRMM among all women with M. genitalium. Women participating in the trial were considered to be at higher risk for STIs as approximately half reported past or present transactional sex. As a result, the observed prevalence and incidence in our study population may be higher than that in the general population. Lastly, data on M. genitalium strain were not available. Therefore, we were unable to determine if women who experienced a second M. genitalium infection experienced an infection with a new strain or if the M. genitalium infection actually persisted, with intervening negative visits being false negatives (i.e. low organism concentration) rather than true negatives.

In summary, our data show that M. genitalium infection is very common among sexually active women in Nairobi and Mombasa, Kenya and Birmingham, Alabama. Given its association with adverse reproductive health outcomes in women, a high prevalence and incidence of M. genitalium could contribute to substantial morbidity. Additional work is needed to definitively demonstrate that M. genitalium causes adverse reproductive health outcomes. [35, 36]. Studies of M. genitalium treatment and prevention will be critical to improving our understanding of this pathogen’s contribution to adverse reproductive outcomes and developing appropriate public health control strategies.

SHORT SUMMARY.

Using retrospective testing of archived specimens, a natural history study of Mycoplasma genitalium among Kenyan and US women reported a high prevalence (11.3%) and incidence of M. genitalium (33.4 per 100 person-years) of M. genitalium.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the women who participated in this study. We gratefully acknowledge the PVI study team and study sites for their tireless work on data and sample collection, and FHI 360 for their work on data management and study operations.

FUNDING

The Preventing Vaginal Infections trial was supported by the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) contract number HHSN266200400073C through the Sexually Transmitted Infections Clinical Trials Group. Mycoplasma genitalium testing was supported by a Developmental Award from the American Sexually Transmitted Disease Association and C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae testing was supported by NIAID (R01 AI099106). RSM receives support for mentoring through K24 HD88229. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the US National Institutes of Health. Infrastructure and logistical support for the Mombasa site was provided through the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI27757).

Footnotes

These data were presented in part at Infectious Disease Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, held 11th–12th August 2016 in Annapolis, MD, USA.

POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

JEB has received donated reagents and test kits from Hologic. RSM currently receives research funding, paid to the University of Washington, from Hologic. J. Schwebke has received consultancy payments from Akesis, Hologic, Symbiomix, and Starpharma, and has grants/pending grants from Akesis, BD Diagnostic, Hologic, Cepheid, Quidel, Symbiomix, Starpharma, and Viamet. LEM has received donated reagents and test kits from Hologic and honoraria for scientific advisory board membership from Hologic and Qiagen, Inc. JSJ has received speaker fees and travel support and research funding via Serum Statens Instiutue (SSI) from Hologic and SSI has performed contract work for SpeeDx, Diagenode, Nytor, Cempra, Angelini, and Nabriva. All other authors declare that they do not have a commercial or other association that might pose a conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JEB, LEM, and RSM conceptualized the article and analysis plan. JEB conducted the analysis in collaboration with LEM, JSJ and RSM. JEB drafted the initial report and LEM, JSJ, and RSM contributed to the content and revisions. OA, JK, J Schwebke, J Shafi, CR, and EK contributed to data collection. All authors contributed to article content and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.McGowin CL, Anderson-Smits C. Mycoplasma genitalium: an emerging cause of sexually transmitted disease in women. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(5):e1001324. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thurman AR, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium symptoms, concordance and treatment in high-risk sexual dyads. Int J STD AIDS. 2010;21(3):177–83. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.008485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tosh AK, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium among adolescent women and their partners. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(5):412–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hjorth SV, et al. Sequence-based typing of Mycoplasma genitalium reveals sexual transmission. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(6):2078–83. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00003-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anagrius C, Lore B, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: prevalence, clinical significance, and transmission. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(6):458–62. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.012062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tully JG, et al. A newly discovered mycoplasma in the human urogenital tract. Lancet. 1981;1(8233):1288–91. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)92461-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manhart LE, Broad JM, Golden MR. Mycoplasma genitalium: should we treat and how? Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(Suppl 3):S129–42. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mavedzenge SN, et al. The association between Mycoplasma genitalium and HIV-1 acquisition in African women. AIDS. 2012;26(5):617–24. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834ff690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lis R, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Manhart LE. Mycoplasma genitalium Infection and Female Reproductive Tract Disease: A Meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(3):418–26. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen JS. Protocol for the detection of Mycoplasma genitalium by PCR from clinical specimens and subsequent detection of macrolide resistance-mediating mutations in region V of the 23S rRNA gene. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;903:129–39. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-937-2_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker J, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium Incidence, Organism Load, and Treatment Failure in a Cohort of Young Australian Women. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(8):1094–100. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gesink DC, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium presence, resistance and epidemiology in Greenland. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2012;71:1–8. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v71i0.18203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chrisment D, et al. Detection of macrolide resistance in Mycoplasma genitalium in France. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(11):2598–601. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Twin J, et al. Transmission and selection of macrolide resistant Mycoplasma genitalium infections detected by rapid high resolution melt analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35593. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salado-Rasmussen K, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium testing pattern and macrolide resistance: a Danish nationwide retrospective survey. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(1):24–30. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dumke R, Thurmer A, Jacobs E. Emergence of Mycoplasma genitalium strains showing mutations associated with macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance in the region Dresden, Germany. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;86(2):221–3. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gesink D, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium in Toronto, Ont: Estimates of prevalence and macrolide resistance. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(2):e96–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Getman D, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium Prevalence, Coinfection, and Macrolide Antibiotic Resistance Frequency in a Multicenter Clinical Study Cohort in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(9):2278–83. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01053-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McClelland RS, et al. Randomized Trial of Periodic Presumptive Treatment with High-Dose Intravaginal Metronidazole and Miconazole to Prevent Vaginal Infections in HIV-negative Women. J Infect Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardick J, et al. Performance of the gen-probe transcription-mediated [corrected] amplification research assay compared to that of a multitarget real-time PCR for Mycoplasma genitalium detection. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(4):1236–40. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.4.1236-1240.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen JS, et al. Azithromycin treatment failure in Mycoplasma genitalium-positive patients with nongonococcal urethritis is associated with induced macrolide resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(12):1546–53. doi: 10.1086/593188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29(2):297–301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.297-301.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balkus JE, et al. Periodic Presumptive Treatment for Vaginal Infections May Reduce the Incidence of Sexually Transmitted Bacterial Infections. J Infect Dis. 2016;213(12):1932–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vandepitte J, et al. Natural history of Mycoplasma genitalium Infection in a Cohort of Female Sex Workers in Kampala, Uganda. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(5):422–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31828bfccf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gomih-Alakija A, et al. Clinical characteristics associated with Mycoplasma genitalium among female sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(10):3660–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00850-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen CR, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium infection and persistence in a cohort of female sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(5):274–9. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000237860.61298.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lokken EM, et al. Recent bacterial vaginosis is associated with acquisition of Mycoplasma genitalium. Am J Epidemiol. 2017 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hay B, et al. Prevalence and macrolide resistance of Mycoplasma genitalium in South African women. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42(3):140–2. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaydos C, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium as a contributor to the multiple etiologies of cervicitis in women attending sexually transmitted disease clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(10):598–606. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181b01948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hancock EB, et al. Comprehensive assessment of sociodemographic and behavioral risk factors for Mycoplasma genitalium infection in women. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(12):777–83. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181e8087e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bjartling C, Osser S, Persson K. Mycoplasma genitalium in cervicitis and pelvic inflammatory disease among women at a gynecologic outpatient service. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(6):476 e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manhart LE, et al. Mucopurulent cervicitis and Mycoplasma genitalium. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(4):650–7. doi: 10.1086/367992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jensen JS, Bradshaw C. Management of Mycoplasma genitalium infections - can we hit a moving target? BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:343. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1041-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horner P, et al. Which azithromycin regimen should be used for treating Mycoplasma genitalium? A meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2017 doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2016-053060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiesenfeld HC, Manhart L. Mycoplasma genitalium in Women: current Knowledge and Research Priorities for This Recently Emerged Pathogen. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(S2):S389–95. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin DH, Manhart L, Workowski KA. Mycoplasma genitalium From Basic Science to Public Health: Summary of the Results From a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Technical Consultation and Consensus Recommendations for Future Research Priorities. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(S2):S427–30. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]