Abstract

ClinVar Miner is a web-based suite that utilizes the data held in the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s ClinVar archive. The goal is to render the data more accessible to processes pertaining to conflict resolution of variant interpretation as well as tracking details of data submission and data management for detailed variant curation. Here we establish the use of these tools to address three separate use-cases and to perform analyses across submissions. We demonstrate that the ClinVar Miner tools are an effective means to browse and consolidate data for variant submitters, curation groups, and general oversight. These tools are also relevant to the variant interpretation community in general.

Keywords: Variant interpretation, variant archive, ClinVar, clinical domain working group, expert panel, variant curation

Introduction

ClinVar is an international, submission-driven archive of variant-condition interpretations hosted by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)(Landrum et al., 2016). It is a key partner of the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen; www.clinicalgenome.org), whose goals include the development of community resources to standardize genomic variant interpretation and facilitate the sharing of genomic data (Harrison et al., 2016; Rehm et al., 2015). ClinVar is increasingly becoming the central repository of interpreted genomic variants; as of January 2018, 879 submitters had contributed 375,106 unique variants to ClinVar. Sharing variants and associated supporting evidence in the ClinVar database enables the transparent review of data by users and can be a valuable resource to support clinical variant interpretation (Harrison et al., 2016).

Submitters to ClinVar include clinical testing labs, researchers, database curators, expert panels and practice guideline groups, and variants are collected from a variety of sources: clinical testing, literature-only evaluation, research, curation, or other. With such a vast amount of data in ClinVar from many types of submitters, it can be difficult for users to discern the validity of variant interpretations, particularly when there are conflicting assertions on the same variant. While the ClinVar team does not modify interpretations, it does aggregate submissions about the same variant and indicates if interpretations are concordant or discordant. As of January 2018 there were 15,503 variation records with conflicting interpretations of pathogenicity (cf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/submitters/). ClinVar assigns a review status to each submission depending on whether the submitter provides assertion criteria and calculates an overall review status for each variant based upon the review status of individual submissions (Figure 1). Assertion criteria must include the categories used by the submitter to classify variants as well as the criteria used to assess each variant (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/docs/review_guidelines/), for example, the ACMG/AMP variant interpretation guidelines (Richards et al., 2015). Groups can apply for the expert panel or practice guideline review status designation via an application process to ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/docs/review_guidelines/). These applications are reviewed by ClinGen (https://www.clinicalgenome.org/expert-groups/). Expert panel and practice guideline groups originate within or external to ClinGen, and all go through the same review and approval processes.

Figure 1.

ClinVar review status designations for submissions and overall variant clinical significance. ClinVar reports the level of review supporting the assertion of clinical significance for the individual submission and for the aggregated variation.

ClinVar provides access to the data in multiple ways. ClinVar provides a monthly release of variant data, in XML and VCF formats (see https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/docs/maintenance_use/). There is also a web portal, the ClinVar database, displaying two views of variant data: the Variation Report – an aggregate of all submissions for a given variant and the Record Report which aggregates variants that are interpreted with respect to the identical condition name based on the mapped MedGen ID. The ClinVar database can be queried using attributes such as HGVS expressions for specific variants, HGNC IDs for genes, and genomic coordinates, and provide variant and gene-oriented data in a tabulated format. The resulting queries can be further filtered by various attributes such as molecular consequence or review status. The ClinVar database is useful for viewing information about a specific variant.

There are, however, multiple other use cases that are difficult to address with the current ClinVar user interface. For one, the identification and management of conflicting variant interpretations is burdensome for submitters who wish to resolve such conflicts. While complete concordance is not expected, joint efforts among clinical laboratories have been successful in resolving discrepancies in classification (Garber et al., 2016; Harrison et al., 2017). To take part in discrepancy resolution, clinical laboratory submitters need to discern clinically significant conflicts so they can identify the source of discordance, share additional data, and reach consensus with other submitters (Harrison et al., 2017). Recent efforts have revealed a variation in levels of discordance in ClinVar based on which types of variants and submitters are considered (Gradishar, Johnson, Brown, Mundt, & Manley, 2017); (Yang et al., 2017). The current ClinVar interface does not enable submitters to easily identify and prioritize their variants with conflicting interpretations. While ClinVar does release a monthly conflict report, it does not provide users with aggregate conflict data, such as which genes have the most conflicts or the number of conflicts between clinical labs and expert panels.

In addition to conflicting variant interpretation resolution, there are several uses of ClinVar data that are difficult with the current interface. For example, ClinGen would benefit from using ClinVar to identify submitters of variants in a gene or disease of interest when forming new expert panels, and later to get input on the creation of disease- or gene-specific variant interpretation guidelines. Additionally, ClinGen leadership teams can use data trends in ClinVar to inform policy decisions, and these groups would benefit from additional aggregated, longitudinal statistics.

To address these needs, we developed ClinVar Miner, an interface for viewing ClinVar data (http://clinvarminer.genetics.utah.edu/). ClinVar Miner complements the existing ClinVar database by enabling exploration of the data at different levels of granularity and from different perspectives. Statistics for current data and, in some cases, for historical data can be viewed relative to all submissions, submitters, conflicting submissions and genes. ClinVar Miner does not currently augment the data released by ClinVar, but presents views of the data that has been made available. Here we describe the functionality of the components of ClinVar Miner and demonstrate use of the tool to investigate some of the trends in the ClinVar database.

Viewing and understanding the complex data within the database from a higher perspective, rather than variant perspective, facilitates archive development and maintenance while also providing significant feedback to contributors on conflicts in interpretation with other submitters. Thus, the exploration of this data with ClinVar Miner leads to improved understanding and increased utility of the data in ClinVar.

User specifications

User specifications for the tools were developed iteratively during bi-weekly meetings with representatives from ClinGen. This group included clinical genetics medical directors, genetic counsellors, clinical genetics fellows, bachelor’s-level biocurators and bioinformaticians. These prospective users of ClinVar Miner provided user stories to illustrate their needs, and provided feedback on the development of the interface. Three primary use cases were identified and the three categories of ClinVar Miner tools, data exploration, conflict exploration, and high-level trends, were built to address each of them.

Use Cases

1. Gene-level data exploration to support curation groups

Expert curation groups, either independent or developed within ClinGen (see https://www.clinicalgenome.org/working-groups/clinical-domain/), are made up of experts in particular disease areas who develop and implement guidance for the standardized interpretation of genomic variants. Gene curation with regards to disease and actionability is a pressing issue, and projects have been funded to carry out these tasks. When curators assemble new curation groups, they may be interested in identifying experts in the field based on the laboratories that submit a significant number of variants in the gene(s) or disease(s) of interest. A gene or disease-centric view of the variants in ClinVar associated with their disease of interest would enable identification of laboratories with the highest number of pathogenic submissions and the most commonly submitted genes and facilitate the formation of curation communities.

2. Conflict exploration to facilitate discrepancy resolution

ClinVar releases a monthly summary of conflicting interpretations which reports all pairwise interpretation differences in ClinVar (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/clinvar/tab_delimited/). While this report is helpful in identifying specific conflicting interpretations, it does not report submitter-, gene-, or review status-specific information on conflicts, such as the number or details of conflicts between specific laboratories, identification of clinically significant conflicts (pathogenic (P) or likely pathogenic (LP) vs. uncertain significance (VUS), likely benign (LB), or benign(B)), the number of conflicts in a given gene, or the number of conflicts with a specific review status (such as expert panels), all of which are important considerations in prioritizing variants for reassessment.

Expert panels, once approved, may also wish to establish expert consensus on variants in their gene(s) of interest with conflicting interpretations. Resolution of these discrepancies by expert panels increases the overall reliability of the data in ClinVar and reduces confusion among users.

3. High-level trends to inform clinical genomic data sharing policy development

It is important for ClinGen members (as well as the curation community in general) to be able to track the growth of the ClinVar database. High-level summaries of the data present in ClinVar support progress reports for funding purposes as well as new initiatives to expand and improve the database. These summaries include the representation of international submitters, overall levels of discordance, and total number of submissions over time.

ClinGen recently put forth a public list of clinical laboratories that meet minimum requirements for data sharing (“Clinical Laboratories Meeting Minimum Requirements for Data Sharing to Support Quality Assurance - ClinGen | Clinical Genome Resource,” n.d.; Rehm, 2017) with the aim to inform clinicians, hospitals, and payers who wish to order genetic testing from laboratories that share data. While many requirements are based off self-reported data by the laboratory, ClinGen requested a submitter-centric view of variants in ClinVar to verify this information. ClinVar Miner incorporated this into the data exploration tools.

Web server implementation

ClinVar Miner is available under the GNU General Public License; the source code is available at https://github.com/eilbecklab/clinvar-miner. It has two main components: An SQLite (https://www.sqlite.org/) database of ClinVar submissions and conflicts, and a Python/Flask ( http://flask.pocoo.org/) web interface to query the database.

A Python script generates the underlying database from ClinVar XML files available from the NCBI (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/clinvar/xml/). This is an extract, transform, and load (ETL) process in which only the most relevant information is kept. First, a submissions table is created where each row represents a submission and the columns represent the submission’s review status, collection method, condition and clinical significance (e.g. pathogenic or benign), etc. Various columns are standardized versions of other columns, for example, the clinical significance is mapped to a standard set of terms and the result is stored in a separate column. After the submissions table has been populated, a comparisons table is generated by joining the submissions table with itself. Each row of this table is a pairwise comparison between two submissions made on the same variant. The clinical significance values of the submissions are compared and a numeric conflict level from 0 to 5 is stored in an additional column. This number corresponds to the type of conflict between the two terms, as defined by the working group (synonymous, confidence, benign/likely benign vs VUS, category and clinically significant), The conflict level is discussed in detail in the Conflict Exploration section.

The web interface to the database is implemented as a Python WSGI application using the Flask web framework. Every URL in the website corresponds to a Python function which runs the appropriate database queries. On some pages, Python is used to reformat the data beyond what SQL ordinarily allows. The data is then passed to an HTML template, where it is used to generate content such as tables. Certain pages use the JavaScript D3 visualization library ( https://d3js.org/) to additionally display a graph or a choropleth. If a submitter annotated a submission with a phenotypic term from MedGen (Halavi, Maglott, Gorelenkov, & Rubinstein, 2013), OMIM (Amberger, Bocchini, Schiettecatte, Scott, & Hamosh, 2015), GeneReviews (Adam et al., 2010), HPO (Köhler et al., 2017), or MeSH (Rogers, 1963), that term is rendered as a link to the database’s website.

In January 2018 the total size of the database was 31.8 GiB, and the database grows by approximately 1.5 GiB with each month’s ClinVar release. To improve performance, the current month’s submissions and comparisons are stored in both the master tables, which contain historical ClinVar data, and separate smaller tables for queries that only need the most up-to-date information. Every table column that can be used in a database query input is indexed. Finally, each web page is cached on both the client and the server rather than running identical database queries and generating the same HTML again. The overall result is wait times of only a few seconds to load most pages, and instantaneous load times for previously visited pages.

Navigating the ClinVar Miner Interface

ClinVar Miner provides eleven mechanisms for exploring ClinVar data. These can be divided into three themes, based on the outlined use-cases: data exploration, conflict exploration, and high-level trends, organized by significance, gene, condition and submitter where applicable.

Data exploration

The Variants by gene and Variants by condition were designed to help users find submissions relating to a particular gene or condition. These pages can be further filtered by review status, collection method, and conflict level. The variants may also be filtered by qualities of the genomic annotation underlying the variant. There are three categories. A variant can intersect a single gene (including regulatory regions), it may intersect two overlapping genes, or it may impact multiple genes. A toggle is also provided to show antisense genes. The default setting is that variants falling in antisense genes are only shown in the sense gene.

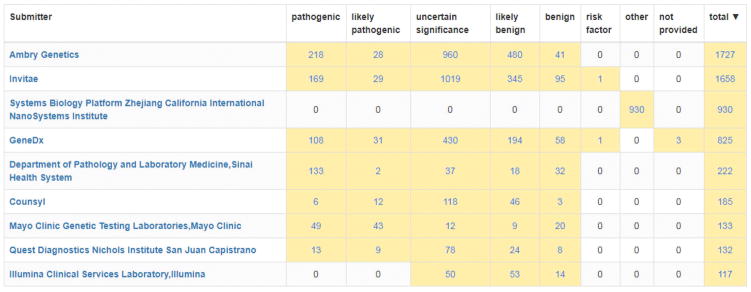

Variants by submitter lists all submitters in ClinVar. After clicking on a submitter, you will see two tables: Gene and significance breakdown and condition and significance breakdown. The rows in these tables correspond to unique genes and conditions, respectively, and the columns correspond to each clinical significance. Clicking a cell will list each variant that falls in the corresponding category and clicking a variant will list all current submissions on that variant.

Variants by gene displays the variant spectra of submitted genes and enables users to identify the top submitters for a particular gene (Figure 2). This tool also enables the sorting of genes by the number of submitters, and the number of variants per gene. A filter is included to discriminate between variants within or near a single gene, variants within overlapping portions of two genes and large variants that disrupt multiple genes.

Figure 2.

A display of the submitter and significance breakdown for the APC gene within the Variants by gene tool. The screen shot displayed has been filtered to include only submitters with submissions with assertion criteria provided but all submitters can be listed if these filters are not applied. This tool can help identify labs to participate in clinical domain working groups and expert panels.

Conflict exploration

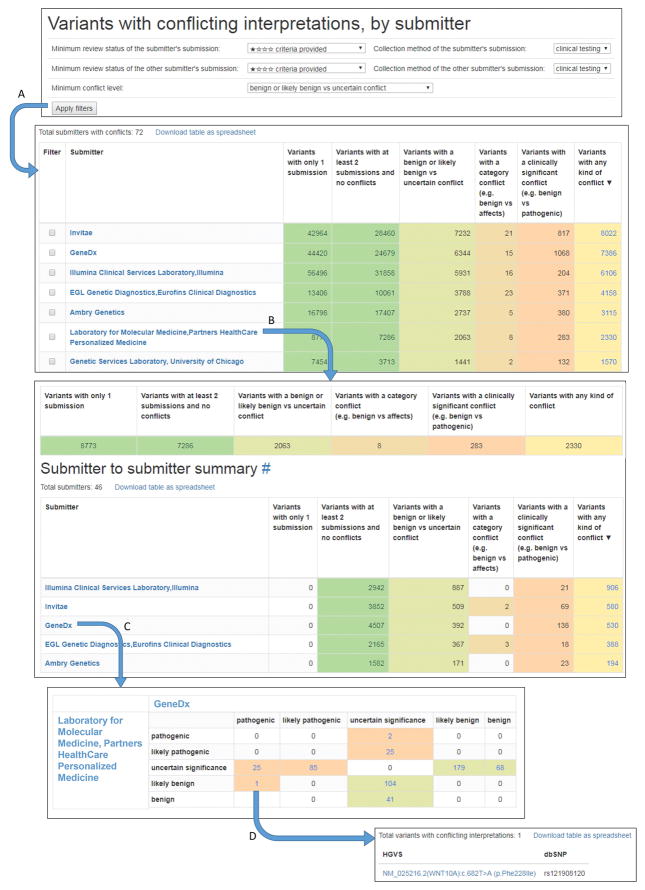

Conflicting interpretations can be extracted and triaged easily by the Variants in conflict by submitter tool, which enables a submitter to view all other submitters with whom they have conflicting interpretations. These submissions can further be filtered by review status and collection method (Figure 3). Conflicts are separated into five levels of conflict: synonymous conflict (benign vs non-pathogenic or pathologic vs pathogenic), confidence conflict (B vs LB or P vs LP), benign or likely benign vs uncertain conflict, category conflict (any of the five standard significance terms vs any non-standard term, such as risk factor or affects), and clinically significant conflict (B, LB, or VUS vs P or LP). Filtering enables the user to prioritize conflicts of interest for resolution efforts. When filtering by review status, each successive review status level includes all conflicts in the levels above it. For example, if you do not select a minimal review status, all conflicts will be shown. However, if you select “criteria provided” as the review status, conflicting variant interpretations will be shown where both submitters in conflict have a review status of “criteria provided” or above (“expert panel”, or “practice guideline”). The conflicting variant interpretations can be further examined via a display of the details from ClinVar of each submission, with the option to open the variation record in ClinVar.

Figure 3.

A workflow showing the Variants in conflict by submitter tool for identifying conflicting interpretations between two individual submitters. The filters at the top of the page apply to all submissions included in subsequent displays. The Minimum conflict level filter allows the user to display For example, setting the review status as ‘criteria provided’ and collection method as ‘clinical testing’ of the submitter of interest and the comparator and setting the minimum conflict level at ‘benign or likely benign vs uncertain conflict’ and clicking the Apply filters button (A) will exclude all submissions that are ‘no criteria provided’ and are not ‘clinical testing’ and will consider as conflicts only LB/B vs VUS conflicts, category conflicts, and clinically significant conflicts. When one or more filters are applied, all calculated conflicts and variants reflect only conflicts or submissions that pass the filter(s). Selecting a laboratory from the list (B) will open a new page displaying a summary of conflicts from that submitter as well as a list of conflicting submitters. Selecting one of those submitters (C) opens a new page displaying only conflicts between the two submitters. Selecting this cell in the table (D) displays a list of variants that the LMM submitted as likely benign and GeneDx submitted as pathogenic.

High-level trends

ClinVar Miner provides summaries of ClinVar data that can be sorted using built-in filters (Figure 4). In order to identify trends over time, ‘Total submissions by method’, displays the growth of ClinVar submissions over time and across collection methods. This graph can be filtered by review status and conflict level. ‘Total submissions by country’, displays a log-scale choropleth with high-submitting countries colored more darkly than low-submitting countries. ClinVar supports a similar global submitter map (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/docs/map/); however, ClinVar’s map is based on number of submitters in each country and the ClinVar Miner map is based on quantity of variant submissions from each country, and enables the use of filters. Finally, ‘significance terms’ charts the total number of clinical significance terms annotated in ClinVar over time. The number of clinical significance terms submitted to ClinVar has plateaued over time (Figure 4). This is because a variety of other significance terms were used for Mendelian variants before standardization by the current guidelines (Richards et al., 2015). In addition, other terms are used for non-Mendelian variants such as ‘risk factor’ and pharmacogenomic effects. It is likely that the total number of terms being submitted will consolidate over time as standardization across all interpretation domains develops. All of these views can be used to inform policy decisions regarding submission and description of data in ClinVar and track quality improvements over time.

Figure 4.

Views of the high-level trends in ClinVar Miner. A) Submissions over time broken down by collection method. B) A choropleth showing number of submissions by country. C) The cumulative number of significance terms submitted to the database over time.

Exploring the ClinVar dataset using ClinVar Miner

ClinVar Miner was used to generate subsets of data to investigate trends within the ClinVar database. All data was current as of January 2018, at which time ClinVar had a total of 580,831 submissions on 375,106 unique variants.

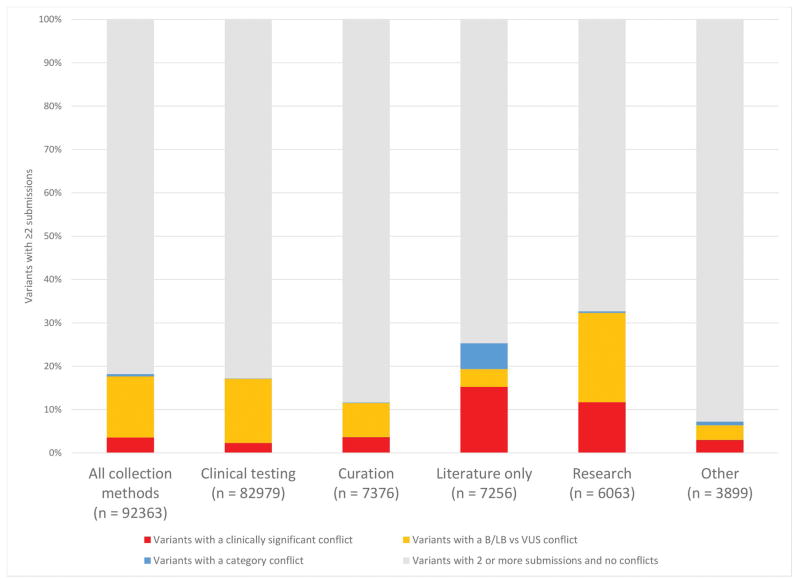

Rates of discordance vary by collection method

We examined rates of discordance and parsed the data by collection method. We used the clinical testing dataset as a reference, given that it was the largest dataset, and then compared within clinical testing and between clinical testing and other collection methods, we used ClinVar Miner to compare concordance of clinical testing submissions with other collection method types (Figure 5). Concordance was measured by the number of variants with two or more submissions and no conflicts. Here, conflicts were considered to be LB/B vs VUS conflicts or clinically significant conflicts (P/LP vs VUS/LB/B). Consistent with prior reports (Yang et al., 2017), this comparison shows that clinical testing submissions have significantly fewer clinically significant conflicts with other clinical testing submissions (2.28%; 1,890 variants with clinically significant conflicts/82,979 variants with two or more submissions) than they do with curation (3.62%; 267/7,376), literature only, which includes OMIM and GeneReviews (15.4%; 1,117/7,256 ), research (11.8%; 718/6,063), and all submissions overall (3.56%; 3,291/92,363). P ≪ 0.001 by the two-proportion z-test. These differences could be due to several factors. Many literature only and research submissions are not assessed using standard clinical interpretation guidelines and are less frequently updated as new information becomes available.

Figure 5.

Concordance and discordance compared to clinical testing submissions. Interpretations from clinical testing submissions, as the largest reference set, were compared to interpretations from each collection method. This data was generated with the Variants in conflict by submitter tool. The “Other” category includes the collection methods case-control, in vivo, in vitro, reference population, provider interpretation, and phenotyping only. Each variant with more than one conflict is counted as its highest conflict level, with clinically significant higher than category which is higher than B/LB vs VUS. Confidence conflicts were not considered conflicts in this analysis.

Submitted variant and conflict counts vary by gene

Variants affecting a total of 27,824 genes have been submitted to ClinVar, 5,822 of which contain variants specific to one gene (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/submitters/). Variants that span multiple genes are either large structural variants, or the underlying gene annotations overlap. For variants affecting a single gene, the ten genes with the most variants are shown in Figure 6. Variants are broken down by clinical significance. A variant is counted for each unique clinical significance assertion, so variants with multiple clinical significances, for example an LP and a VUS submission, count towards each of these categories. It should be noted that variants annotated with a clinical significance of “other”, “not provided”, or “risk factor” are not shown in this graph. Seven of the top ten genes (BRCA2, BRCA1, APC, MSH6, MSH2, LDLR, and TSC2) are on the ACMG gene list for reporting of incidental findings (Kalia et al., 2017).

Figure 6.

The top 10 genes with the most variants submitted to ClinVar. The Variants by gene tool was used to generate this data. For each of these genes the number and types of conflict are also shown. Only submissions normalized to the five standard significance terms were included. The Variants in conflict by gene tool was used to provide the number of conflicting submissions for each gene. The ATM gene also contains variants that affect both ATM and C11orf65, an overlapping non-coding gene.

Variants of uncertain significance are the most common variants submitted for the top ten genes except BRCA1 and LDLR. Pathogenic assertions were the most common clinical significance submitted in BRCA1 (2505, 36% of submissions) and LDLR (1413, 43%). LDLR also had a noticeably low proportion of VUS submissions (435, 13%). APC had a large number of variants classified as “other” due to a single large submission that did not specify a clinical significance (data not shown).

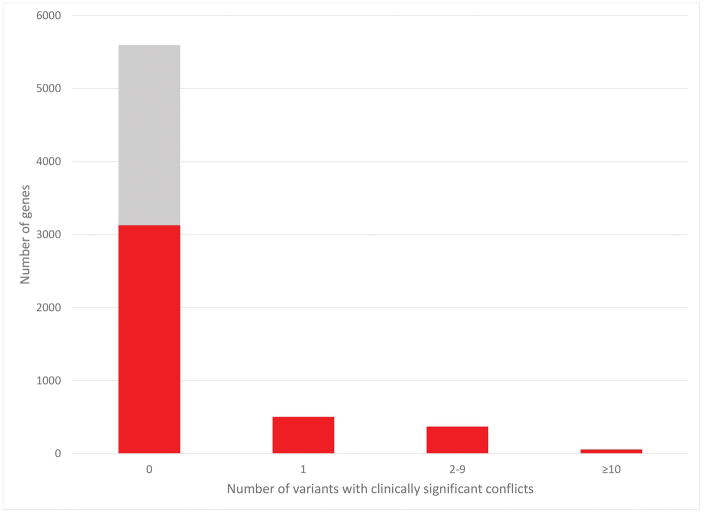

While these ten genes, which are definitively associated with monogenic disease, account for 12% (45,554/375,106) of the total unique variants in ClinVar, the vast majority (77%) of genes in ClinVar have submissions of fewer than 50 variants (data not shown). A similar outcome is shown for the frequency of clinically significant conflicts (Figure 7). 77% (3126/4058) of genes with more than one submitter have no clinically significant conflicts and 99% (4002/4058) of genes with greater than one submitter have fewer than 10 clinically significant conflicts. Interestingly, 36% (2317/6375) of all genes have submissions from only one submitter (Figure 7; grey bar), indicating many genes may have only limited clinical validity (Strande et al., 2017). These data highlight the overall concordance of interpretations submitted to ClinVar but also the continued need for both variant discrepancy resolution and thorough gene-level clinical validity curation.

Figure 7.

Frequency of clinically significant conflicting interpretations of variants per gene. The gray region represents genes with only one submitter within which conflicts could not occur. Variants were limited to those affecting only one gene, thereby excluding larger copy number variants.

Submitted conditions

While the majority of assertions in ClinVar are made with respect to disease terms such as those found in OMIM or MedGen, or with detailed phenotypic information in the case of most copy-number variants, there are a large proportion of variants with asserted conditions of either ‘not specified’ or ‘not provided’. Submitters often use the term ‘not specified’ when a variant is benign for all known disease associations for the gene, and the term ‘not provided’ when the submitting lab has either not defined a specific disease association or has not tracked this information in their system. There are 109,902 and 37,074 variants with ‘not specified’ or ‘not provided’ submissions, respectively, including 651 likely pathogenic or pathogenic variants submitted with the condition ‘not specified’, suggesting a gap in tracking the associated conditions in many submissions.

There is also high variability in the condition terms submitted for specific genes. Although in some cases, genes have more than one associated condition for which variants may be interpreted, in most cases the conditions should be the same but the specific condition name is chosen from multiple disease ontology/terminology systems preventing the ability to appropriately aggregate the assertions around a single condition. For example, five of the six most-submitted conditions in ClinVar all refer to breast and ovarian cancer but are slightly different names for the same condition.

Discussion

ClinVar was launched to facilitate the sharing of genomic variant interpretation among laboratories, and has become an asset to clinical testing and research (Harrison et al. 2016; Rehm 2017; Yang et al. 2017). The ClinVar online interface is optimized for exploration of variant-phenotype assertions from a variant-centric clinical perspective. ClinVar Miner is an adjunct interface that was built around three additional use cases that are vital to the clinical genetics community, but also pertinent to many other applications of ClinVar data. The use cases we address include review and prioritization of conflicting variant interpretations, data submission analysis for expert panels and the provision of data summaries for ClinGen oversight and policy development.

We have provided 11 tools that slice, dice and filter the ClinVar dataset to address important questions about content and trends within the database. The scope of these tools is to present the data currently in ClinVar in ways that address use-cases. These tools do not augment the existing data, but use filters to improve understanding of submissions, gene-level analyses and conflicting variant interpretations. Three high-level trends tools provide views and graphs of aggregated ClinVar data that distill the current data into impactful figures that display overall progress. Four data exploration tools display variants sorted by significance, gene, condition, or submitter. Four conflict exploration tools display conflicting variant interpretations annotated with significance, gene, condition, and submitter to better enable the process of variant interpretation conflict resolution. At each stage these variants can be filtered on review status, submitter type and conflict level. These data outputs enable a deeper understanding of ClinVar submissions and conflicts.

In agreement with Yang et al, (2017) we show clinical testing submissions are highly concordant with each other compared to submissions from literature-only and research sources. Nevertheless, as more data is shared, the need for discrepancy resolution is vital to maintaining the integrity of the database. As demonstrated by Harrison et al. (2017) prior to ClinVar Miner, conflicting variant interpretation resolution between four clinical laboratories required close collaboration with the ClinVar team to produce boutique data reports pertaining to those submitters. ClinVar Miner has made that information readily and transparently available. We hope this resource encourages and facilitates participation in conflict resolution activities.

An important distinction must be made between variants that are conflict-free because multiple submitters agree on the assertion, and variants that have no conflicts because they have only one submission. The former category, in which there is concordance between submitters, can be thought of as more substantiated than those variants with only one submission. We have reflected this distinction on all the conflict exploration tools in ClinVar Miner. Another aspect of conflicting variant interpretation is the level of support for each assertion. A variant where a single lab offers one interpretation opposed to multiple others with an alternate interpretation should be easier to resolve than a variant where the interpretations are split more evenly between all submitters. A future development to ClinVar Miner could be to develop a metric to convey the number of assertions for each classification.

Confidence conflicts, or those between likely benign and benign or likely pathogenic and pathogenic, while not calculated as conflicts by ClinVar, may still have long-term clinical implications. In our experience, it is more common for likely pathogenic and likely benign interpretations to change over time than pathogenic or benign interpretations when new data becomes available or variant assessment rules change. Therefore, we have included confidence conflicts in ClinVar Miner to provide additional granularity on conflicting interpretations that are often overlooked. For example, if a variant had two laboratories with likely pathogenic assertions and one with a pathogenic assertion, a user may be more cautious about that variant’s pathogenicity than if three laboratories all agreed on pathogenic. Furthermore, the clinical genetics community is in the midst of discussions as to whether laboratories should include both likely pathogenic and pathogenic variants versus only pathogenic, when returning secondary findings in clinical reports.

We found widespread inconsistencies in condition terms submitted to ClinVar. This makes it challenging to aggregate ClinVar data based on condition, a feature that would greatly aid expert panels concerned with particular conditions or clinical domains. This highlights a need for standardization of disease terms and integration of ClinVar with a disease ontology database. Inconsistent terms hinder the searchability and sortability of ClinVar data in outside applications. ClinGen is developing a resource of preferred condition terms (https://www.clinicalgenome.org/share-your-data/laboratories/preferred-condition-list/) that will help guide submitters in creating consistency in their interpreted diseases.

The ClinVar database is an invaluable tool for clinical and scientific exploration of genomic variant interpretations and accordingly is utilized by many kinds of users. ClinVar Miner provides up-to-date views of the data that enable a greater understanding and expanded use of ClinVar’s content and drives further quality improvement of this vital resource.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NHGRI U41 HG006834-01A1 (to H.R.) and U01HG007437–01 (to Jonathan Berg). N.R-S. is a recipient of an NLM training grant scholarship (T15LM007124). We also acknowledge the efforts of Lisa Vincent, Scott Goehringer, Erin Riggs and Christa Martin who supported the development of this tool through thoughtful discussion as well as Justin Aronson who developed a prior tool, Variant Explorer, that helped define useful functionality for ClinVar Miner. The NCBI ClinVar team lead by Melissa Landrum rapidly answered our questions and let us use their monthly community call to demonstrate the tool and solicit feedback.

Footnotes

Author contributions

A.H. developed website. S.E.H., B.C., M.D., D.A., S.M.H., and H.R. designed and specified features of website. S.E.H., N. R-S and K.E. analyzed data downloaded from website. A.H, S.E.H. and K.E. wrote manuscript with input from other coauthors.

References

- Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Mefford HC, … Ledbetter N, editors. GeneReviews(®) Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, Schiettecatte F, Scott AF, Hamosh A. OMIM.org: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM®), an online catalog of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;43(Database issue):D789–D798. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical Laboratories Meeting Minimum Requirements for Data Sharing to Support Quality Assurance - ClinGen. Clinical Genome Resource. n.d Retrieved February 6, 2018, from https://www.clinicalgenome.org/lablist/

- Garber KB, Vincent LM, Alexander JJ, Bean LJH, Bale S, Hegde M. Reassessment of Genomic Sequence Variation to Harmonize Interpretation for Personalized Medicine. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2016;99(5):1140–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradishar W, Johnson K, Brown K, Mundt E, Manley S. Clinical Variant Classification: A Comparison of Public Databases and a Commercial Testing Laboratory. The Oncologist. 2017;22(7):797–803. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halavi M, Maglott D, Gorelenkov V, Rubinstein W. MedGen. National Center for Biotechnology Information; US: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison SM, Dolinsky JS, Knight Johnson AE, Pesaran T, Azzariti DR, Bale S, … Rehm HL. Clinical laboratories collaborate to resolve differences in variant interpretations submitted to ClinVar. Genetics in Medicine: Official Journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2017;19(10):1096–1104. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison SM, Riggs ER, Maglott DR, Lee JM, Azzariti DR, Niehaus A, … Rehm HL. Using ClinVar as a Resource to Support Variant Interpretation. Current Protocols in Human Genetics / Editorial Board, Jonathan L. Haines ... [et Al. ] 2016;89:8.16.1–8.16.23. doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg0816s89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia SS, Adelman K, Bale SJ, Chung WK, Eng C, Evans JP, … Miller DT. Recommendations for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, 2016 update (ACMG SF v2.0): a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genetics in Medicine: Official Journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2017;19(2):249–255. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler S, Vasilevsky NA, Engelstad M, Foster E, McMurry J, Aymé S, … Robinson PN. The Human Phenotype Ontology in 2017. Nucleic Acids Research. 2017;45(D1):D865–D876. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Benson M, Brown G, Chao C, Chitipiralla S, … Maglott DR. ClinVar: public archive of interpretations of clinically relevant variants. Nucleic Acids Research. 2016;44(D1):D862–D868. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm HL. A new era in the interpretation of human genomic variation. Genetics in Medicine: Official Journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2017;19(10):1092–1095. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm HL, Berg JS, Brooks LD, Bustamante CD, Evans JP, Landrum MJ … ClinGen. ClinGen--the Clinical Genome Resource. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(23):2235–2242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1406261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J … ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genetics in Medicine: Official Journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2015;17(5):405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers FB. Medical subject headings. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association. 1963;51:114–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strande NT, Riggs ER, Buchanan AH, Ceyhan-Birsoy O, DiStefano M, Dwight SS, … Berg JS. Evaluating the Clinical Validity of Gene-Disease Associations: An Evidence-Based Framework Developed by the Clinical Genome Resource. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2017;100(6):895–906. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Lincoln SE, Kobayashi Y, Nykamp K, Nussbaum RL, Topper S. Sources of discordance among germ-line variant classifications in ClinVar. Genetics in Medicine: Official Journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2017;19(10):1118–1126. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]