Abstract

The genetic susceptibility to preeclampsia, a pregnancy-specific complication with significant maternal and fetal morbidity, has been poorly characterized. To identify maternal genes associated with preeclampsia risk, we assembled 498 cases and 1,864 controls of European ancestry from preeclampsia case-control collections in five different US sites (with additional matched population controls), genotyped samples on a cardiovascular gene-centric array comprised of variants from approximately 2,000 genes selected based on prior genetic studies of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, and performed case-control genetic association analysis on 27,429 variants passing quality control. In-silico replication testing of 9 lead signals with p<10−4 was carried out in independent European samples from the SOPHIA and Inova cohorts (212 cases, 456 controls). Multi-ethnic assessment of lead signals was then performed in samples of African-American (26 cases, 136 controls), Hispanic (132 cases, 468 controls), and East Asian (9 cases, 80 controls) ancestry. Multi-ethnic meta-analysis (877 cases, 3,004 controls) revealed a study-wide statistically significant association of the rs9478812 variant in the pleiotropic PLEKHG1 gene (OR 1.40 (1.23-1.60, pmeta=5.90 × 10−7). The rs9478812 effect was even stronger in the subset of European cases with known early-onset preeclampsia (236 cases diagnosed < 37 weeks, 1,864 controls; OR 1.59 (1.27-1.98), p=4.01 × 10−5). PLEKHG1 variants have previously been implicated in genome-wide association studies of blood pressure, body weight, and neurological disorders. While larger studies are required to further define maternal preeclampsia heritability, this study identifies a novel maternal risk locus for further investigation.

Keywords: preeclampsia, genetic association studies, pregnancy, hypertension, pleckstrin homology domain-containing family G

INTRODUCTION

Preeclampsia is a common pregnancy-specific multisystem disorder, characterized by systemic endothelial dysfunction in the mother, with both maternal (pulmonary edema, acute renal failure, liver failure, stroke, and placental abruption) and fetal/neonatal complications (preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, hypoxic-neurologic injury, and perinatal death). Despite extensive investigative efforts, preeclampsia remains a significant source of both fetal and maternal morbidity and mortality1.

Preeclampsia is associated with an increased long-term risk of maternal cardiovascular diseases (CVD), including ischemic heart disease and stroke2–9. Approximately a decade after a preeclamptic pregnancy, a woman’s risk of ischemic heart disease is elevated approximately 2-fold2,5–7,9. Two hypotheses prevail regarding preeclampsia and future CVD risk: (1) women with preeclampsia are predisposed to CVD, and that the vascular and metabolic challenge of normal pregnancy exposes this predisposition10; and/or (2) preeclampsia causes vascular and metabolic changes which remain following pregnancy and increase a woman’s future risk11.

Preeclampsia has a substantial heritable component as demonstrated in multiple epidemiologic studies, with heritability estimated at 55-60%, of which 30-35% is attributed to a maternal genetic effect and 20% fetal12–15. Understanding preeclampsia heritability has proved challenging due to multiple factors including the heterogeneous nature of the disease, combined complex genetic and environmental risk factors, as well as the contribution of at least two genomes (maternal and fetal) to each pregnancy outcome. To overcome these challenges, ideal genetic studies of preeclampsia would have adequate sample sizes, detailed clinical characterization, paired maternal-fetal samples, and replication of significant genetic loci from the discovery population in an independent cohort16. The recently published fetal preeclampsia GWAS utilized several of these study design improvements, leading to the identification of the genome-wide significant fetal variant near the FLT1 gene17. Maternal genetic variants contributing to preeclampsia risk remain elusive; despite many candidate gene association studies (summarized in 18) and three recently reported GWAS19–21, there are no maternal variants that have been robustly and reproducibly associated. Strategies utilizing paired maternal-fetal samples have been underutilized to date, but are likely to reveal significant interacting genetic loci, as demonstrated by the increased preeclampsia risk conferred by specific combinations of maternal killer immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) and fetal HLA-C alleles22,23.

In an effort to better define the maternal genetics of preeclampsia and to identify shared genetic factors for PE and CVD, we tested for the genetic association of common variants with preeclampsia in women of European ancestry from the United States (US; 498 cases, 1,864 controls) using the Human CVD Beadarray 50K SNP ® (Illumina), also referred to as the ITMAT-Broad-CARe (IBC) genotyping array, that captures genetic diversity across >2000 candidate gene regions related to cardiovascular, inflammatory, and metabolic phenotypes24. We tested for replication of genetic variants with p<10−4 in two independent case-control populations of European ancestry (Study of Pregnancy Hypertension in Iowa (SOPHIA): 177 cases, 116 controls19, and Inova: 35 cases, 340 controls25, and extended association analyses to women of African-American (26 cases, 136 controls), Hispanic (132 cases, 468 controls), and East Asian (9 cases, 80 controls) ancestry for a trans-ethnic meta-analysis (877 cases, 3,004 controls).

METHODS

Data sharing

The five US site European preeclampsia GWAS summary statistics (Discovery population; described below) have been made publicly available and can be accessed at https://richa-saxena.squarespace.com (Data section).

Study Population

Discovery population: preeclampsia case-control collections

Case women with preeclampsia during pregnancy and matched normotensive control women were identified from five US sites with IRB-approved protocols, as detailed below. Preeclampsia case status at all sites was defined by standard American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologist (ACOG) criteria26,27. Specifically, preeclampsia diagnosis was determined based on systolic blood pressures (SBP) ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressures (DBP) ≥90 mmHg or higher on two occasions at least 4 hours apart occurring after 20 weeks gestation in women whose blood pressure had previously been normal, as well as new-onset proteinuria with ≥300 mg protein in a 24-hour urine specimen, a protein/creatinine ratio of at least 0.3, or ≥1+ protein on urine dipstick. Cases of superimposed preeclampsia (women with chronic hypertension with worsening SBP ≥160 mmHg or DBP ≥110 mmHg at least 4 hours apart occurring after 20 weeks gestation, as well as new-onset or worsening proteinuria) and HELLP syndrome (defined by red blood cell hemolysis, elevated liver transaminases at least twice normal concentration, and platelet count <100,000/μL) were also included.

1. Boston Hospital collections

Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH)/ Brigham & Women’s Hospital (BWH)

Billing records of women who delivered at MGH and BWH from 1995-2011 were queried for preeclampsia-related ICD-9 codes. When patients returned to participating sites, blood samples drawn for clinical diagnostic testing were obtained at their point of discard. Preeclampsia diagnosis was validated by physician electronic medical record (EMR)/ chart review with a 30-day time-limited link to protected health information. DNA was extracted from buffy coats of de-identified accessioned samples. Because the investigators did not interact with patients for data or sample ascertainment, the Partners Human Research Committee waived the informed consent requirement (detailed by 45 CFR 46.116). In total, 244 validated cases (230 preeclampsia, 14 superimposed preeclampsia) of European ancestry were obtained. Additional African-American (n=5) and Hispanic (n=23) preeclampsia cases were obtained for the multi-ethnic meta-analysis. Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC). Nineteen preeclampsia cases and 74 normotensive age-matched controls of European ancestry with healthy, term pregnancies were identified from an ongoing, maternal blood collection at BIDMC with preeclampsia diagnosis determined by physician case review. Additional African-American (1 preeclampsia case, 9 controls) and Hispanic (6 preeclampsia cases, 1 superimposed preeclampsia case, 17 controls) participants were obtained for the multi-ethnic meta-analysis. DNA was extracted from maternal blood samples using the Paxgene collection system (BD).

2. University of Southern California (USC) collections

HELLP Syndrome Society/ HELLP Syndrome Research at USC

Cases were recruited using internet-based methods, either from the HELLP Syndrome Society website (no longer functional) or from the HELLP Syndrome Research at USC Facebook page. Controls were unrelated friends of the cases and their families. To verify case status, medical records were requested and reviewed by study investigators. Saliva samples (Oragene DNA Self-Collection Kit) or buccal samples for DNA were obtained at each participant’s home and mailed to the investigators for DNA extraction. In total, 80 preeclampsia/HELLP cases of European ancestry were utilized. Los Angeles County + University of Southern California Medical Center. Hispanic cases (n=59) and normotensive controls (n=95), as well as an African-American control (n=1), were recruited retrospectively from delivery logs at the Los Angeles County and University of Southern California Women’s and Children’s Hospital from 1999 to 2006, as well as during their postpartum stay at the hospital from 2007-200828. Medical charts were abstracted and reviewed to verify preeclampsia case and normotensive control status. Women with lupus, renal disease, multiple gestations, and sickle cell disease were excluded. Maternal DNA was obtained from blood, mouthwash, buccal swabs, or saliva, as previously described28.

3. Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) collection

DNA from European (69 cases, 345 controls), African-American (10 cases, 41 controls), and Hispanic (3 cases, 11 controls) women was collected from 2009–2012 at the Center for Applied Genomics (CAG) at CHOP through A Study of the Genetic Causes of Complex Pediatric Disorders (GCPD). Mothers of recruited children were asked if they had ever had preeclampsia during their pregnancy and gave written informed consent to allow access to their medical records. Preeclampsia diagnosis was confirmed by medical record review. Maternal DNA from whole blood was extracted using the Agencourt Genfind v2 DNA purification system (Beckman Coulter) on an automated Biomek-FX (Beckman Coulter). Maternal DNA from saliva was extracted using the Agencourt DNAdvance protocol (Beckman Coulter) on an automated Biomek-FX.

4. Yale-New Haven Hospital collection

DNA from European (11 cases, 30 controls), African-American (1 case, 16 controls), and Hispanic (13 cases, 170 controls) women was collected from the March of Dimes Perinatal Emphasis Research Initiative (PERI) project at New York University, NY and from Yale-New Haven Hospital, New Haven, CT from January 1989 to June 2005. Maternal blood was collected at the time of preeclampsia diagnosis, after written consent was obtained. Buffy coats from blood samples were obtained, and DNA subsequently extracted by standard methods. All specimens were linked with the medical records.

5. University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics collection

DNA from 77 preeclamptic women (of European (n=75), African-American (n=1), and Hispanic (n=1) ethnicity) collected from 1996–2005 at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics was used for this study. Maternal DNA was extracted from buccal swab or peripheral blood sample. Preeclampsia diagnosis was verified by medical record review.

Population-based Controls

To enhance power to detect genetic associations, population-based unselected European control women from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) studies, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC; n=645)29 and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA; n=770)30, with IBC array genotype data from the Candidate gene Association Resource (CARe)31, were matched to the case population.

Replication Populations

SOPHIA study

The SOPHIA Caucasian cohort of 177 preeclampsia cases and 116 normotensive controls was recruited using electronic birth certificates from the Iowa Department of Public Health from 3078 primiparous women who gave birth in Iowa from August 2002 to May 2005, as previously described19. Genotyping was performed using the Affymetrix Genome-Wide SNP Array 6.0 (Affymetrix). Sample quality control and data analysis was performed, as previously described19.

Inova Health System study

The multi-ethnic Inova cohort of 78 preeclampsia cases and 664 normotensive controls was recruited at Inova Fairfax Medical Campus (Falls Church, Virginia) during 2011-2013 as part of the IRB-approved Molecular Study of Preterm Birth genomic research study. Clinician chart review was performed to categorize women as hypertensive or normotensive, and a second chart review was performed to confirm the diagnosis of preeclampsia in women in the hypertensive group using the same criteria as the Boston Hospitals collection. Whole genome sequencing was performed on whole blood samples by Complete Genomics, Inc. (Mountain View, CA) and processed as previously described32. The 9 SNPs tested for replication fulfilled genotype quality control criteria (100% call rate, allele balance >=0.225, read depth >=9, allele read depth >=6, a quality score not VQLOW, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium p> 0.001). Ancestry was computed by performing principal components analysis on the genomic data from the Inova cohort and from 1,815 individuals from the 1000 Genomes Project33, with population labels assigned to the Inova cohort using the k-nearest neighbor algorithm and the first 10 principal components.

Discovery population: genotyping and quality control

Case and control DNA samples from the 5 US site discovery population were genotyped on a cardiovascular gene-centric 50 K SNP array v1.0 (45,707 markers), v2.0 (49,094 markers), or v3.0 (53,831 markers)24. SNPs were clustered into genotypes using the Beadstudio software ® (Illumina) and subjected to quality control at the sample and SNP level. Genotypes for the population control sample (ARIC, n=649; CARDIA, n=770) were generated by the Broad Institute as part of the CARe study31. Within Europeans, samples were excluded for individual call rates <90% (n=0), sex mismatch (n=0), heterozygosity >3 SD from the mean (n=3) and excess relatedness (pi-hat>0.2 (n=16)). Only SNPs present in all three versions of the 50K SNP array (38,138 overlapping SNPs) were included: 2,692 SNPs were removed for call rates <95%, no SNPs were removed for departure from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p<10−7 in controls), 8,017 SNPs were removed for minor allele frequency (MAF) <0.01, and no SNPs were removed for differential missingness between cases and controls (p<10−6). Overall SNP call rate per sample was consistent across all 5 US sites. After quality control, 27,429 SNPs in 498 cases and 1864 controls were successfully tested in our discovery sample.

Statistical Analysis

Evaluation of population stratification

Genetic ancestry of cases and normotensive controls was determined using principal components (PCs) analysis (Figure S1). Ten eigenvectors were calculated from all overlapping SNPs in the 1000 Genomes Project (1KGP) from European, African, and Asian reference populations34 and were projected onto our sample. Based on distance to the nearest continental cluster, we defined samples as of European, African-admixed, or Asian-admixed ancestry. Concordance of self-report with genetic cluster was 93.1% for Europeans, 66.0% for African-admixed and 96.4% for Asian-admixed samples.

Association testing

European IBC array single SNP association analysis

Association testing was performed using logistic regression with the SNP coded in an additive genetic model and including adjustment for 10 PCs (calculated in the cleaned European sample) to correct for subtle population structure. To correct for multiple comparisons, based on an estimated 20,500 independent tests on the ITMAT-Broad-CARe (IBC) genotyping array in Europeans, the study-wide statistical threshold of significance was set to p=2.4 × 10−6 35.

Admixture-informed association analysis in African-American and Hispanic populations

For African-American and Hispanic patients from the 5 US site collection, HAPMIX and MIXSCORE were used to jointly calculate a SNP association score conditioned on local ancestry using logistic regression and a case-only admixture score which evaluates the causal hypothesis that, restricting to disease cases, the proportion of one ancestry at the candidate locus differs from the genome-wide proportion36.

Replication analysis in SOPHIA and Inova

Directly genotyped lead SNPs or proxy SNPs (r2>0.5 in 1000 Genomes Northern Europeans from Utah (1KGP CEU)) from the 9 lead association signals in our study were interrogated in the previously described SOPHIA Caucasian maternal preeclampsia GWAS (177 preeclampsia cases, 116 normotensive controls) genotyped on the Affymetrix SNP 6.0 microarray19. These 9 lead association signals (all directly genotyped by whole genome sequencing) were also interrogated in the subset of European cases from the Inova study (35 preeclampsia cases, 340 normotensive controls). Logistic regression was performed for each ancestry group with PLINK v1.90 using the first 10 principal components as covariates (www.cog-genomics.org/plink/1.9)37.

Meta-analysis

Results were combined across discovery and replication studies, and across ethnicities, using a fixed effects, inverse variance meta-analysis approach38.

Gene and Pathway Analysis

We performed gene-based association testing using VEGAS39 for 6,804 genes containing one or more SNPs. The significance threshold was set at p<7.35×10−6 after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. To screen for pathways enriched among the top-most associated hits, we used the pathway analysis tool DEPICT v.1 rel 17340. SNPs with p<10−3 were included in the DEPICT gene set analysis.

RESULTS

Ethnicity and collection sites of preeclampsia cases and normotensive controls are described in the online-only Data Supplement (please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org; Table S1). Site-specific characteristics of each case-control cohort are described in the Methods.

Of the European preeclampsia cases included in the discovery population (n=498), more detailed clinical information was available for 71% (n=354), including cases from the Boston, USC, and Yale sites but not Iowa or CHOP sites (see Table S2). Of the 354 characterized cases, 201 were cases of early-onset preeclampsia with diagnosis < 37 weeks gestation, 101 were cases of hemolysis-elevated liver enzymes-low platelets (HELLP) syndrome, and 215 were cases with severe features (e.g., severe range blood pressures, abnormal laboratory studies, maternal symptoms). This means that, in the discovery population, at least 40% of the preeclampsia cases were early-onset, 29% had HELLP syndrome, and 43% had severe features. Birth weight was not well-ascertained in many of the study collections; thus, information on intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) was not available.

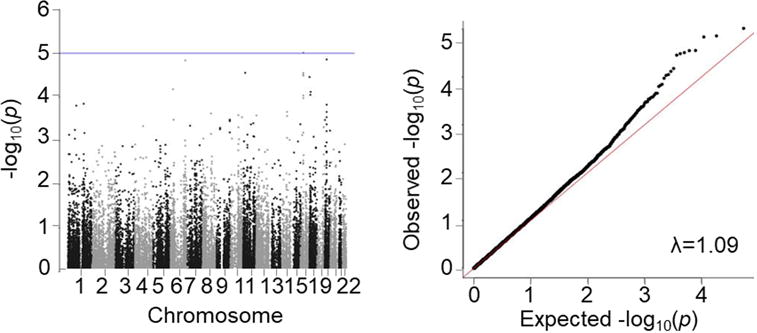

Gene-centric association analysis in sample of European ancestry

Association testing for preeclampsia in samples of European ancestry revealed little inflation from undetected population structure or relatedness (λ =1.09; Figure 1). No study-wide significant signals were observed, but 9 independent signals reached suggestive significance (p<10−4; IBC Discovery, Table 1). No evidence of independent replication of the 9 association signals was seen in the European replication population (SOPHIA and Inova, Table 1; see Table S3 for directly genotyped and proxy SNPs with r2>0.5 in the 1KGP CEU population in SOPHIA). However, in European meta-analysis including the SOPHIA and Inova populations, while no SNP surpassed the IBC array-wide significance threshold, a SNP within the PLEKHG1 gene, rs11155751 (later renamed rs9478812 in the dbSNP database), showed greater evidence of association than in either study alone (OR 1.41 (1.22 -1.64), p=5.49 × 10−6; European Combined, Table 1). A sensitivity analysis by US site demonstrated consistent directionality of effect for rs9478812 across the 5 sites (Table S4). Additionally, the rs9478812 effect was even stronger in the subset of European cases with known early-onset preeclampsia (236 cases diagnosed < 37 weeks, 1,864 controls; OR 1.59 (1.27-1.98), p=4.01 × 10−5).

Figure 1.

Manhattan and q-q plots of PE association results in women of European ancestry (SNPs >1% frequency for n =498 cases, n =1,864 controls).

Table 1.

Genetic association results: discovery, replication, and meta-analysis in samples of European ancestry.

| IBC Discovery (5 US sites) | Replication (SOPHIA† + Inova) | European Combined (Discovery + Replication) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (498 cases, 1864 controls) | (212 cases, 456 controls) | (710 cases, 2320 controls) | ||||||

| SNP Chr: position* |

Gene | EA/OA EAF |

OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P |

| rs303016 6:25139464 |

LRRC16 | T/C 0.17 |

1.44 (1.20 – 1.72) | 6.66 × 10−5 | 1.26 (0.91 – 1.73) | 0.16 | 1.39 (1.19 – 1.63) | 3.08 × 10−5 |

|

rs9478812‡ 6:151095379 |

PLEKHG1 |

A/G 0.22 |

1.44 (1.22 – 1.70) | 1.46 × 10−5 | 1.30 (0.91 – 1.85) | 0.14 | 1.41 (1.22 – 1.64) | 5.49 × 10−6 |

| rs11024739 11:18645843 |

SPTY2D1 | C/A 0.27 |

1.39 (1.19 – 1.63) | 2.80 × 10−5 | 0.90 (0.64 – 1.25) | 0.53 | 1.29 (1.12 – 1.48) | 4.16 × 10−4 |

| rs1110470 16:27336427 |

IL4R | A/G 0.47 |

0.75 (0.65 – 0.87) | 9.28 × 10−5 | 1.20 (0.91 – 1.59) | 0.20 | 0.83 (0.73 – 0.94) | 3.95 × 10−3 |

| rs3024630 16:27366126 |

IL4R | G/A 0.09 |

1.68 (1.33 – 2.11) | 9.65 × 10−6 | 0.81 (0.50 – 1.33) | 0.41 | 1.47 (1.20 – 1.81) | 2.43 × 10−4 |

| rs11656003 17:1979792 |

SMG6 | A/G 0.09 |

1.59 (1.28 – 1.98) | 3.50 × 10−5 | 0.95 (0.33 – 2.08) | 0.82 | 1.45 (1.19 – 1.77) | 2.51 × 10−4 |

| rs3764429 17:10025298 |

GAS7 | A/G 0.08 |

1.60 (1.27 – 2.02) | 8.93 × 10−5 | 0.82 (0.59 – 1.52) | 0.68 | 1.54 (1.22 – 1.93) | 2.18 × 10−4 |

| rs1984661 17:12650777 |

MYOCD | C/T 0.42 |

1.34 (1.16 – 1.54) | 7.66 × 10−5 | 1.07 (0.64 – 1.77) | 0.80 | 1.31 (1.14 – 1.51) | 1.08 × 10−4 |

| rs867616 19:1957682 |

EDG4 | T/C 0.19 |

1.47 (1.23 – 1.74) | 1.39 × 10−5 | 1.12 (0.80 – 1.55) | 0.51 | 1.38 (1.19 – 1.61) | 3.28 × 10−5 |

Position from hg19.

See Table S3 for proxy SNPs used for the SOPHIA replication. Proxy SNPs were not available in the SOPHIA genotyping data for IBC array SNPs rs3764429 and rs1984661.

rs11155751 listed on the IBC array has been merged by dbSNP into alias rs9478812.

Transferability of lead European association signals to multi-ethnic samples

Next, we performed SNP association analysis in the 5 US site African-American and Hispanic preeclampsia case-control populations also genotyped with the IBC array, and q-q plots confirmed little inflation (λ =0.99, African-American; λ =1.08, Hispanic; Figure S2a,b). We then tested for transferability of the 9 lead European association signals to the combined 5 US site + Inova multi-ethnic preeclampsia case-control samples (African-American, Hispanic, and East Asian ancestries) (Table 2). Combined analysis across ethnic groups for the 9 SNPs led to one study-wide significant association, rs9478812 in PLEKHG1; p=5.90 × 10−7 (Table 2). A forest plot of the association of rs9478812 by ethnic group and in combined analysis is shown in Figure S3.

Table 2.

Cross-ethnic investigation of 9 lead European association signals.

| African-American (5 US sites + Inova) | Hispanic (5 US sites + Inova) | East Asian (Inova) | Trans-ethnic meta-analysis (5 US sites + SOPHIA + Inova) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (26 cases, 136 controls) | (132 cases, 468 controls) | (9 cases, 80 controls) | (877 cases, 3004 controls) | |||||

| SNP Gene |

OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P |

| rs303016 LRRC16 |

0.92 (0.37 – 2.29) | 0.86 | 1.07 (0.73 – 1.57) | 0.73 | 0.34 (0.03 – 3.72) | 0.38 | 1.32 (1.15 – 1.53) | 1.15 × 10−4 |

|

rs9478812* PLEKHG1 |

0.76 (0.32 – 1.83) | 0.55 | 1.49 (1.10 – 2.01) | 9.7 × 10−3 | 0.70 (0.18 – 2.75) | 0.61 | 1.40 (1.23 – 1.60) | 5.90 × 10−7 |

| rs11024739 SPTY2D1 |

1.71 (0.55 – 5.34) | 0.35 | 0.88 (0.64 – 1.22) | 0.45 | 1.07 (0.32 – 3.59) | 0.92 | 1.22 (1.07 – 1.38) | 2.62 × 10−3 |

| rs1110470 IL4R |

0.86 (0.42 – 1.77) | 0.68 | 1.16 (0.86 – 1.56) | 0.33 | 0.46 (0.11 – 1.97) | 0.30 | 1.15 (1.02 – 1.29) | 1.80 × 10−2 |

| rs3024630 IL4R |

1.30 (0.26 – 6.44) | 0.75 | 1.10 (0.47 – 2.59) | 0.82 | – | – | 1.45 (1.19 – 1.77) | 2.84 × 10−4 |

| rs11656003 SMG6 |

0.39 (0.07 – 2.28) | 0.30 | 0.79 (0.47 – 1.33) | 0.37 | – | – | 1.32 (1.10 – 1.59) | 2.88 × 10−3 |

| rs3764429 GAS7 |

0.32 (0.07 – 1.42) | 0.14 | 0.69 (0.42 – 1.14) | 0.15 | 0.58 (0.08 – 4.42) | 0.60 | 1.29 (1.05 – 1.59) | 1.35 × 10−2 |

| rs1984661 MYOCD |

0.70 (0.29 – 1.70) | 0.44 | 1.01 (0.72 – 1.41) | 0.96 | 0.71 (0.17 – 3.10) | 0.65 | 1.24 (1.10 – 1.41) | 6.75 × 10−4 |

| rs867616 EDG4 |

0.90 (0.08 – 10.2) | 0.93 | 0.34 (0.09 – 1.25) | 0.11 | – | – | 1.35 (1.16 – 1.57) | 8.77 × 10−5 |

rs11155751 listed on the IBC array has been merged by dbSNP into alias rs9478812

Pathway analyses

While SNPs on the IBC array cover candidate genes, SNP associations do not necessarily identify the causal variants or genes. Using evidence from multiple independent association signals in gene- or pathway-based analyses can enhance power to detect associations, identify causal genes, and point to causal biological processes41,42. Therefore, we performed gene- and pathway-based association analyses on the European discovery population.

Gene-based VEGAS analysis prioritized one gene: IL4R, that encodes the alpha chain of the interleukin-4 receptor (Table S5). DEPICT analysis40 prioritized four genes with FDR<20%, SELE, BAG3, C6orf72, and PPP1R3B (Table S6a). One gene set defining the protein-protein interaction (PPI) subnetwork for the phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit 3 (PIK3R3) was most significantly enriched (FDR<20%; Table S6b). Enriched tissues included urogenital structures, blood vessels, and keratinocytes (FDR <20%; Table S6c).

DISCUSSION

In this large maternal gene-centric association study of preeclampsia, we find a multi-ethnic study-wide significant association of rs9478812, a SNP which lies within an intronic region of the pleiotropic gene, PLEKHG1.

PLEKHG1 is a large gene (232 kb) with 15 exons that encodes the PLEKHG1 protein, a Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor expressed across a wide range of tissues (Figure S4a). Despite its ubiquitous expression, the function of PLEKHG1 is largely unknown. SNPs within PLEKHG1 have been associated with blood pressure traits (i.e., both systolic and diastolic blood pressure) in multi-ethnic GWAS43, suggesting that this region may be important in BP regulation. The PLEKHG1 locus has also been identified in GWAS of sickle cell anemia44, cognitive decline45, obesity-related traits46, alcohol and nicotine co-dependence47, and panic disorder48. PLEKHG1 knockout mice exhibit a sex-specific phenotype, with a reduction in the peripheral blood granulocytes (i.e., polymorphonuclear lymphocytes, PML) in female mice only (male granulocyte number is normal) (Antonella Galli, Mouse Pipeline Team, Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus; personal communication, November 8, 2017); thus, PLEKHG1 may influence PML production and/or function specifically in females. Additionally, the PLEKHG1 protein has been implicated in actin cytoskeletal organization and can mediate cyclic stretch-induced perpendicular reorientation of endothelial cells in a model of endothelial mechanical force loading49.

The phenotypes and molecular processes associated with PLEKHG1 suggest many potential mechanisms by which alterations at this genetic locus could alter maternal preeclampsia risk. As PLEKHG1 locus has been associated with hypertensive disease in other GWAS43, variants within this region may predispose women to develop hypertensive disease in pregnancy. Hypertensive disease could be mediated by altered vascular endothelial cell response to stress, given the demonstrated role of PLEKHG1 within endothelial cells49, or by effects on the kidney since renal PLEKHG1 gene expression increases in an angiotensin II-induced mouse model of hypertension50. Additionally, as knockout mouse data emphasizes the role of PLEKHG1 in mediating female PMLs (Antonella Galli, personal communication, November 8, 2017), PLEKHG1 risk variants could alter PML production and/or function, leading to changes in the innate and adaptive immune responses. Interestingly, women with severe preeclampsia have notable leukocytosis (attributed to expansion of the neutrophil population, the most predominant PML)51,52, which may be a sign of increased acute inflammation versus alterations in the adaptive immune system53–55. Furthermore, neutrophils have been implicated in endothelial injury in women with preeclampsia56, and neutrophils from preeclamptic women have increased adhesion to endothelial cells versus neutrophils from healthy pregnant women57.

Regarding the specific genetic locus tagged by the study-significant SNP, rs9478812, this SNP lies within an intronic region of PLEKHG1 in a region predicted to bind the protein SETDB1, a histone methyltransferase important for gene silencing. The G to A change at rs9478812 (A, effect allele; G, other allele; see Table 1) is predicted to alter the binding sites of transcription factors, GATA and HLTF (Figure S4b). Thus, the region tagged by rs9478812 is likely to be functionally important and, consequently, may be the specific region responsible for increasing preeclampsia risk. However, rs9478812 is in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with many intronic SNPs within PLEKHG1; the biological annotation of the common variants in LD with rs9478812 is shown in Figure S4b. The array used for genotyping in this GWAS lacks the coverage necessary to further delineate the specific causal SNPs. Therefore, to identify the causal SNP(s) in this region, and to determine the impact of the SNP(s) on gene function, fine-mapping and experimental functional follow-up will be necessary.

In addition to the lead signal observed within PLEKHG1, gene- and pathway-based approaches suggested enrichment of: modules associated with the IL4 receptor (IL4R); the genes SELE, BAG3, C6orf72, and PPP1R3B; and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3) kinase signaling. Many of these genes and pathways have been implicated in preeclampsia pathogenesis and are discussed in further detail below. Enriched tissues included urogenital structures and blood vessels, two specific tissues types that would be predicted to be important in maternal predisposition to preeclampsia.

IL4R encodes for the alpha chain of the interleukin-4 receptor, which binds IL4 and IL13 leading to regulation of IgE and differentiation of Th2 cells. Increased IL4 levels during pregnancy promote Th2 responses and inhibit Th1 responses; these alterations are important for fetal tolerance by the mother58. In mice, when IL4 is deficient, a phenotype akin to preeclampsia (i.e., hypertension and proteinuria) develops58. In humans, altered mid-pregnancy levels of circulating maternal IL4R have been associated with later preeclampsia59. Women with preeclampsia have decreased levels of IL4 and increased levels of circulating IL4R60–62. Additionally, specific combinations of maternal and fetal genetic variants within IL4R are enriched in preeclamptic pregnancies63.

SELE encodes E-selectin; variants in SELE have been associated with coronary artery disease and hypertension64–66. BAG3 encodes for the Bcl2-associated athanogene 3 (BAG3) protein, a member of the BAG family of co-chaperones that interact with the heat shock protein 70 ATPase domain. BAG3 increases in response to stressful stimuli and modulates key biologic processes, including development, apoptosis, cytoskeletal organization, and autophagy67. Interestingly, genetic variants in BAG3 have been associated with cardiomyopathy68,69, a condition significantly more likely in women with preeclampsia and with overlapping pathophysiology70. PPP1R3B encodes the catalytic subunit of the serine/threonine phosphatase, protein phosphatase-1. PPP1R3B genetic variants influence lipid levels71 and C-reactive protein (CRP)72,73. Genetic predisposition to dyslipidemia and altered CRP levels have been associated with increased preeclampsia risk74,75. Women with hyperlipidemia76 and elevated CRP77 are at increased risk of preeclampsia (although the risk may be modified by BMI). PI3 kinase signaling is important for endothelial cell homeostasis and response to vascular injury78,79, key processes disrupted in women with preeclampsia.

Strengths of this maternal preeclampsia GWAS include the size of the discovery sample (relative to prior studies), enrichment of early-onset and severe cases in the discovery cohort, inclusion of a replication cohort, and increased association of the lead signal that reaches study-wide significance in trans-ethnic association analysis. Limitations of the study include the lack of detailed clinical information on a subset of the preeclampsia cases, the use of population controls (leading to enhanced power to detect associations but increased likelihood of misclassification), and the lack of paired fetal samples. Additionally, as the genotyping array coverage was restricted to genes only, we are limited in our ability to determine if the lead SNP, rs9478812, is the causal variant responsible for increased maternal preeclampsia risk. Future work will focus on replication of rs9478812 in additional cohorts, fine-mapping the genomic region surrounding rs9478812, and functional follow-up of PLEKHG1 to determine how alterations at the locus predispose to the development of preeclampsia.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVES.

In summary, we report here the largest multi-ethnic maternal preeclampsia GWAS study to date that reveals a multi-ethnic study-wide significant association within the PLEKHG1 locus, as well as associations with processes with established roles in maternal preeclampsia pathophysiology and long-term cardiovascular disease risk, including vascular, endothelial, and cellular stress pathways. This GWAS identifies and prioritizes a new genetic locus for future studies; these studies should aim to define the specific mechanisms by which alterations in this genomic region influence preeclampsia risk. Further delineation of maternal and fetal preeclampsia heritability will require the establishment of larger preeclampsia consortia with detailed clinical phenotyping, paired maternal-fetal samples, and genome-wide genotyping and/or sequencing data. These efforts have the potential to significantly advance our understanding of preeclampsia biology.

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is New?

Preeclampsia has significant heritability, but genetic risk factors are poorly understood.

This is largest maternal genome-wide association study (GWAS) of preeclampsia to date and identifies a study-wide significant variant within the PLEKHG1 gene, a locus identified in GWAS of other traits including blood pressure, body weight, and neurological disorders.

What Is Relevant?

This study highlights a plausible maternal gene candidate previously implicated in hypertension, providing a new biological clue into pathways dysregulated in preeclampsia.

Summary.

We report here results from the largest maternal multi-ethnic GWAS of preeclampsia, which reveals a novel locus associated with preeclampsia risk within the pleiotropic PLEKHG1 gene. While larger studies will be required to identify additional genetic associations, this study provides support for using GWAS to understand preeclampsia hereditability.

Acknowledgments

We thank Roger Williamson and David C. Merrill for their contributions to the University of Iowa Hospital and Clinics sample collection.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by a Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology Gertie Marx Research grant (to RS and BTB), funds from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to SAK), NIH K08 HD075831 grant (to BTB), NIH F32 HD86948 grant (to KJG), NIH T32 HL007427 grant (to HM), and March of Dimes grants #21-FY05-1250 (to ERN), NIH R21 HD046624 (to SAI), and #20-FY03-30 (to CJL). The SOPHIA study was supported by NIH R01 HD32579 grant (to AFS) and the Verto Institute. DLB, EK, and KCH were supported by the Inova Health System.

BTB is an investigator on grants to his institution from Lilly, Pfizer, Baxalta, and GSK for unrelated projects.

Footnotes

Conflict(s) of Interest/Disclosure(s). All other authors have no conflicts.

References

- 1.Mol BWJ, Roberts CT, Thangaratinam S, Magee LA, de Groot CJM, Hofmeyr GJ. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):999–1011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith GC, Pell JP, Walsh D. Pregnancy complications and maternal risk of ischaemic heart disease: a retrospective cohort study of 129,290 births. Lancet. 2001;357(9273):2002–2006. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wikström A-K, Haglund B, Olovsson M, Lindeberg SN. The risk of maternal ischaemic heart disease after gestational hypertensive disease. BJOG. 2005;112(11):1486–1491. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pell JP, Smith GCS, Walsh D. Pregnancy complications and subsequent maternal cerebrovascular events: a retrospective cohort study of 119,668 births. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(4):336–342. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kestenbaum B, Seliger SL, Easterling TR, Gillen DL, Critchlow CW, Stehman-Breen CO, Schwartz SM. Cardiovascular and thromboembolic events following hypertensive pregnancy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(5):982–989. doi: 10.1016/j.ajkd.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald SD, Malinowski A, Zhou Q, Yusuf S, Devereaux PJ. Cardiovascular sequelae of preeclampsia/eclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Am Heart J. 2008;156(5):918–930. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellamy L, Casas J-P, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ. Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;335(7627):974. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.385301.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haukkamaa L, Salminen M, Laivuori H, Leinonen H, Hiilesmaa V, Kaaja R. Risk for subsequent coronary artery disease after preeclampsia. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(6):805–808. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ray JG, Vermeulen MJ, Schull MJ, Redelmeier DA. Cardiovascular health after maternal placental syndromes (CHAMPS): population-based retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2005;366(9499):1797–1803. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67726-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sattar N, Greer IA. Pregnancy complications and maternal cardiovascular risk: opportunities for intervention and screening? BMJ. 2002;325(7356):157–160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7356.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rich-Edwards JW, McElrath TF, Karumanchi SA, Seely EW. Breathing life into the lifecourse approach: pregnancy history and cardiovascular disease in women. Hypertension. 2010;56(3):331–334. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.156810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cnattingius S, Reilly M, Pawitan Y, Lichtenstein P. Maternal and fetal genetic factors account for most of familial aggregation of preeclampsia: a population-based Swedish cohort study. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;130A(4):365–371. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esplin MS, Fausett MB, Fraser A, Kerber R, Mineau G, Carrillo J, Varner MW. Paternal and maternal components of the predisposition to preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(12):867–872. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103223441201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nilsson E, Salonen Ros H, Cnattingius S, Lichtenstein P. The importance of genetic and environmental effects for pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension: a family study. BJOG. 2004;111(3):200–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00042x.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomsen LCV, Melton PE, Tollaksen K, Lyslo I, Roten LT, Odland ML, Strand KM, Nygård O, Sun C, Iversen A-C, Austgulen R, Moses EK, Bjørge L. Refined phenotyping identifies links between preeclampsia and related diseases in a Norwegian preeclampsia family cohort. J Hypertens. 2015;33(11):2294–2302. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laivuori H. Pitfalls in setting up genetic studies on preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2013;3(2):60. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGinnis R, Steinthorsdottir V, Williams NO, et al. Variants in the fetal genome near FLT1 are associated with risk of preeclampsia. Nat Genet. 2017;49(8):1255–1260. doi: 10.1038/ng.3895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Staines-Urias E, Paez MC, Doyle P, Dudbridge F, Serrano NC, Ioannidis JPA, Keating BJ, Hingorani AD, Casas JP. Genetic association studies in pre-eclampsia: systematic meta-analyses and field synopsis. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(6):1764–1775. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao L, Triche EW, Walsh KM, Bracken MB, Saftlas AF, Hoh J, Dewan AT. Genome-wide association study identifies a maternal copy-number deletion in PSG11 enriched among preeclampsia patients. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao L, Bracken MB, DeWan AT. Genome-wide association study of pre-eclampsia detects novel maternal single nucleotide polymorphisms and copy-number variants in subsets of the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study cohort. Ann Hum Genet. 2013;77(4):277–287. doi: 10.1111/ahg.12021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson MP, Brennecke SP, East CE, et al. Genome-wide association scan identifies a risk locus for preeclampsia on 2q14, near the inhibin, beta B gene. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hiby SE, Apps R, Sharkey AM, Farrell LE, Gardner L, Mulder A, Claas FH, Walker JJ, Redman CW, Redman CC, Morgan L, Tower C, Regan L, Moore GE, Carrington M, Moffett A. Maternal activating KIRs protect against human reproductive failure mediated by fetal HLA-C2. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(11):4102–4110. doi: 10.1172/JCI43998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiby SE, Walker JJ, O’Shaughnessy KM, Redman CWG, Carrington M, Trowsdale J, Moffett A. Combinations of maternal KIR and fetal HLA-C genes influence the risk of preeclampsia and reproductive success. J Exp Med. 2004;200(8):957–965. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keating BJ, Tischfield S, Murray SS, et al. Concept, design and implementation of a cardiovascular gene-centric 50 k SNP array for large-scale genomic association studies. PLoS One. 2008;3(10):e3583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong WSW, Solomon BD, Bodian DL, Kothiyal P, Eley G, Huddleston KC, Baker R, Thach DC, Iyer RK, Vockley JG, Niederhuber JE. New observations on maternal age effect on germline de novo mutations. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10486. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122–1131. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000437382.03963.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ACOG practice bulletin. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. Number 33. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(1):159–167. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01747-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson ML, Desmond DH, Goodwin TM, Miller DA, Ingles SA. Maternal and fetal variants in the TGF-beta3 gene and risk of pregnancy-induced hypertension in a predominantly Latino population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(3):295 e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. The ARIC investigators. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(4):687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, Hughes GH, Hulley SB, Jacobs DR, Jr, Liu K, Savage PJ. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(11):1105–1116. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Musunuru K, Lettre G, Young T, et al. Candidate gene association resource (CARe): design, methods, and proof of concept. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3(3):267–275. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.882696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bodian DL, McCutcheon JN, Kothiyal P, Huddleston KC, Iyer RK, Vockley JG, Niederhuber JE. Germline variation in cancer-susceptibility genes in a healthy, ancestrally diverse cohort: implications for individual genome sequencing. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.1000 Genomes Project Consortium. Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Garrison EP, Kang HM, Korbel JO, Marchini JL, McCarthy S, McVean GA, Abecasis GR. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526(7571):68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.1000 Genomes Project Consortium. Abecasis GR, Altshuler D, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Gibbs RA, Hurles ME, McVean GA. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467(7319):1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saxena R, Elbers CC, Guo Y, et al. Large-scale gene-centric meta-analysis across 39 studies identifies type 2 diabetes loci. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(3):410–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Price AL, Tandon A, Patterson N, Barnes KC, Rafaels N, Ruczinski I, Beaty TH, Mathias R, Reich D, Myers S. Sensitive detection of chromosomal segments of distinct ancestry in admixed populations. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(6):e1000519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LC, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 2015;4:7. doi: 10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(17):2190–2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu JZ, McRae AF, Nyholt DR, Medland SE, Wray NR, Brown KM, AMFS Investigators. Hayward NK, Montgomery GW, Visscher PM, Martin NG, Macgregor S. A versatile gene-based test for genome-wide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87(1):139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pers TH, Karjalainen JM, Chan Y, et al. Biological interpretation of genome-wide association studies using predicted gene functions. Nat Commun. 2015;6:5890. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang K, Li M, Bucan M. Pathway-based approaches for analysis of genomewide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(6):1278–1283. doi: 10.1086/522374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. Analysing biological pathways in genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(12):843–854. doi: 10.1038/nrg2884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Franceschini N, Fox E, Zhang Z, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of blood-pressure traits in African-ancestry individuals reveals common associated genes in African and non-African populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93(3):545–554. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhatnagar P, Barron-Casella E, Bean CJ, Milton JN, Baldwin CT, Steinberg MH, Debaun M, Casella JF, Arking DE. Genome-wide meta-analysis of systolic blood pressure in children with sickle cell disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sherva R, Tripodis Y, Bennett DA, Chibnik LB, Crane PK, de Jager PL, Farrer LA, Saykin AJ, Shulman JM, Naj A, Green RC, GENAROAD Consortium, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Consortium Genome-wide association study of the rate of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(1):45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Comuzzie AG, Cole SA, Laston SL, Voruganti VS, Haack K, Gibbs RA, Butte NF. Novel genetic loci identified for the pathophysiology of childhood obesity in the Hispanic population. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zuo L, Zhang F, Zhang H, Zhang X-Y, Wang F, Li C-SR, Lu L, Hong J, Lu L, Krystal J, Deng H-W, Luo X. Genome-wide search for replicable risk gene regions in alcohol and nicotine co-dependence. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2012;159B(4):437–444. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Otowa T, Yoshida E, Sugaya N, Yasuda S, Nishimura Y, Inoue K, Tochigi M, Umekage T, Miyagawa T, Nishida N, Tokunaga K, Tanii H, Sasaki T, Kaiya H, Okazaki Y. Genome-wide association study of panic disorder in the Japanese population. J Hum Genet. 2009;54(2):122–126. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2008.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abiko H, Fujiwara S, Ohashi K, Hiatari R, Mashiko T, Sakamoto N, Sato M, Mizuno K. Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors involved in cyclic-stretch-induced reorientation of vascular endothelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2015;128(9):1683–1695. doi: 10.1242/jcs.157503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liang J, Le TH, Edwards DRV, et al. Single-trait and multi-trait genome-wide association analyses identify novel loci for blood pressure in African-ancestry populations. PLoS Genet. 2017;13(5):e1006728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Canzoneri BJ, Lewis DF, Groome L, Wang Y. Increased neutrophil numbers account for leukocytosis in women with preeclampsia. Am J Perinatol. 2009;26(10):729–732. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1223285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lurie S, Frenkel E, Tuvbin Y. Comparison of the differential distribution of leukocytes in preeclampsia versus uncomplicated pregnancy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1998;45(4):229–231. doi: 10.1159/000009973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosales C, Demaurex N, Lowell CA, Uribe-Querol E. Neutrophils: Their Role in Innate and Adaptive Immunity. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:1469780. doi: 10.1155/2016/1469780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lampé R, Kövér Á, Szűcs S, Pál L, Árnyas E, Ádány R, Póka R. Phagocytic index of neutrophil granulocytes and monocytes in healthy and preeclamptic pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol. 2015;107:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lampé R, Kövér Á, Szűcs S, Pál L, Árnyas E, Póka R. The effect of healthy pregnant plasma and preeclamptic plasma on the phagocytosis index of neutrophil granulocytes and monocytes of nonpregnant women. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2017;36(1):59–63. doi: 10.1080/10641955.2016.1237644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clark P, Boswell F, Greer IA. The neutrophil and preeclampsia. Semin Reprod Endocrinol. 1998;16(1):57–64. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1016253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsukimori K, Tsushima A, Fukushima K, Nakano H, Wake N. Neutrophil-derived reactive oxygen species can modulate neutrophil adhesion to endothelial cells in preeclampsia. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21(5):587–591. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2007.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chatterjee P, Chiasson VL, Bounds KR, Mitchell BM. Regulation of the Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines Interleukin-4 and Interleukin-10 during Pregnancy. Front Immunol. 2014;5:253. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taylor BD, Tang G, Ness RB, Olsen J, Hougaard DM, Skogstrand K, Roberts JM, Haggerty CL. Mid-pregnancy circulating immune biomarkers in women with preeclampsia and normotensive controls. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2016;6(1):72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saito S, Sakai M, Sasaki Y, Tanebe K, Tsuda H, Michimata T. Quantitative analysis of peripheral blood Th0, Th1, Th2 and the Th1:Th2 cell ratio during normal human pregnancy and preeclampsia. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;117(3):550–555. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00997.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arriaga-Pizano L, Jimenez-Zamudio L, Vadillo-Ortega F, Martinez-Flores A, Herrerias-Canedo T, Hernandez-Guerrero C. The predominant Th1 cytokine profile in maternal plasma of preeclamptic women is not reflected in the choriodecidual and fetal compartments. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2005;12(5):335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jonsson Y, Rubèr M, Matthiesen L, Berg G, Nieminen K, Sharma S, Ernerudh J, Ekerfelt C. Cytokine mapping of sera from women with preeclampsia and normal pregnancies. J Reprod Immunol. 2006;70(1-2):83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goddard KAB, Tromp G, Romero R, et al. Candidate-gene association study of mothers with pre-eclampsia, and their infants, analyzing 775 SNPs in 190 genes. Hum Hered. 2007;63(1):1–16. doi: 10.1159/000097926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Faruque MU, Chen G, Doumatey A, Huang H, Zhou J, Dunston GM, Rotimi CN, Adeyemo AA. Association of ATP1B1, RGS5 and SELE polymorphisms with hypertension and blood pressure in African-Americans. J Hypertens. 2011;29(10):1906–1912. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834b000d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Qin L, Zhao P, Liu Z, Chang P. Associations SELE gene haplotype variant and hypertension in Mongolian and Han populations. Intern Med. 2015;54(3):287–293. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liao B, Chen K, Xiong W, Chen R, Mai A, Xu Z, Dong S. Relationship of SELE A561C and G98T Variants With the Susceptibility to CAD. Medicine. 2016;95(8):e1255. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rosati A, Graziano V, De Laurenzi V, Pascale M, Turco MC. BAG3: a multifaceted protein that regulates major cell pathways. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e141. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Arimura T, Ishikawa T, Nunoda S, Kawai S, Kimura A. Dilated cardiomyopathy-associated BAG3 mutations impair Z-disc assembly and enhance sensitivity to apoptosis in cardiomyocytes. Hum Mutat. 2011;32(12):1481–1491. doi: 10.1002/humu.21603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Norton N, Li D, Rieder MJ, Siegfried JD, Rampersaud E, Züchner S, Mangos S, Gonzalez-Quintana J, Wang L, McGee S, Reiser J, Martin E, Nickerson DA, Hershberger RE. Genome-wide studies of copy number variation and exome sequencing identify rare variants in BAG3 as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(3):273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Patten IS, Rana S, Shahul S, et al. Cardiac angiogenic imbalance leads to peripartum cardiomyopathy. Nature. 2012;485(7398):333–338. doi: 10.1038/nature11040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature. 2010;466(7307):707–713. doi: 10.1038/nature09270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dehghan A, Dupuis J, Barbalic M, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in >80 000 subjects identifies multiple loci for C-reactive protein levels. Circulation. 2011;123(7):731–738. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.948570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ligthart S, de Vries PS, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, CHARGE Inflammation working group. Franco OH, Chasman DI, Dehghan A. Pleiotropy among common genetic loci identified for cardiometabolic disorders and C-reactive protein. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0118859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Spracklen CN, Saftlas AF, Triche EW, Bjonnes A, Keating B, Saxena R, Breheny PJ, Dewan AT, Robinson JG, Hoh J, Ryckman KK. Genetic Predisposition to Dyslipidemia and Risk of Preeclampsia. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(7):915–923. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Spracklen CN, Smith CJ, Saftlas AF, Triche EW, Bjonnes A, Keating BJ, Saxena R, Breheny PJ, Dewan AT, Robinson JG, Hoh J, Ryckman KK. Genetic predisposition to elevated levels of C-reactive protein is associated with a decreased risk for preeclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2017;36(1):30–35. doi: 10.1080/10641955.2016.1223303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Spracklen CN, Smith CJ, Saftlas AF, Robinson JG, Ryckman KK. Maternal hyperlipidemia and the risk of preeclampsia: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(4):346–358. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rebelo F, Schlüssel MM, Vaz JS, Franco-Sena AB, Pinto TJP, Bastos FI, Adegboye ARA, Kac G. C-reactive protein and later preeclampsia: systematic review and meta-analysis taking into account the weight status. J Hypertens. 2013;31(1):16–26. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835b0556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mukai Y, Rikitake Y, Shiojima I, Wolfrum S, Satoh M, Takeshita K, Hiroi Y, Salomone S, Kim H-H, Benjamin LE, Walsh K, Liao JK. Decreased vascular lesion formation in mice with inducible endothelial-specific expression of protein kinase Akt. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(2):334–343. doi: 10.1172/JCI26223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cudmore MJ, Ahmad S, Sissaoui S, Ramma W, Ma B, Fujisawa T, Al-Ani B, Wang K, Cai M, Crispi F, Hewett PW, Gratacós E, Egginton S, Ahmed A. Loss of Akt activity increases circulating soluble endoglin release in preeclampsia: identification of inter-dependency between Akt-1 and heme oxygenase-1. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(9):1150–1158. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.