Abstract

Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are immune cells that lack specific antigen receptors but possess similar effector functions as T cells. Concordantly, ILCs express many transcription factors known to be important for T cell effector function. ILCs develop from lymphoid progenitors in fetal liver and adult bone marrow. However, the identification of ILC progenitor (ILCP) and other precursors in peripheral tissues raises the question of whether ILC development might occur at extramedullary sites. We discuss central and local generation in maintaining ILC abundance at peripheral sites.

Keywords: Innate lymphoid cells, ILC distribution, Central progenitors, Development, Homing, Peripheral ILC generation

Introduction

Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are considered innate counterparts of effector T cells. ILCs have been classified into three main subsets or types. Type 1 ILCs comprise conventional natural killer (NK) cells and ILC1; type 2 ILCs consist of ILC2; and Type 3 ILCs comprise ILC3 and Lymphoid Tissue inducer cells (LTi) [1]. The classification of ILCs is based on their expression of defining transcription factors and their functional characteristics, including their distinct cytokine production ability [1]. Additionally, recent evidence suggests the existence of ILC subsets functionally intermediate between the main ILC groups [2–8]. Whether these new subsets represent plasticity or are distinct lineages of ILC is presently unknown.

ILC immune effector functions are strikingly similar to T cells [9]. Like CD8+ T cells, NK cells are cytotoxic to tumor cells and virus-infected cells. The signature cytokines secreted by Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells are produced by ILC1, ILC2 and ILC3 respectively [10]. ILCs and T cells share transcriptional networks that are perhaps responsible for the similarities of their immune functions [11, 12]. Despite striking similarities between T cell and ILC effector functions, ILCs lack some unique features that distinguish them from T cells. They lack recombination activating gene (RAG)-dependent rearrangement of antigen specific receptors, and so would be predicted to lack immune memory. However, some reports suggest that long-lived ILC2s as well as NK cells do possess memory type characteristics [13, 14]. Similar to innate-like T cells, ILCs are naturally distributed in various lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues [15].

ILC development was initially studied at primary hematopoietic sites, which are the bone marrow in adult mice or liver in fetal mice [16]. However, many recent studies report the presence of ILC progenitors in peripheral tissues and organs in mouse and human, suggesting the existence of peripheral ILC development [17]. It is unclear to what extent the development and functional programming of ILC subsets occurs centrally versus at peripheral sites. ILC development at peripheral sites could allow generation of specific classes of ILCs tailored to local environments.

We review here recent advances in understanding the progressive steps of central ILC development in adult mice, and discuss some of the evidence for peripheral ILC development. We propose that migration of ILC progenitors in addition to ILC may economically allow tissues to elicit development and expansion of specific ILC types appropriate for each tissue.

ILC subsets and their sites of prevalence

ILC subsets are widely distributed throughout the body [18]. ILCs have been isolated from primary lymphoid organs such as bone marrow and thymus, as well as from secondary lymphoid organs, peripheral blood and non-lymphoid tissues such as lung, small intestine, skin, liver, uterus, colon, and fat [19, 20]. ILC1s are found in liver, intestinal lamina propria as well as the intraepithelial (IE) compartment [21]. ILC1s produce large amounts of IFN-γ and protect against intracellular pathogens like Clostridium difficile and Toxoplasma gondii [22, 23]. NK cells are found in the bone marrow, liver, lymph nodes and spleen [24]; and can kill target cells through the release of perforins and granzymes [25]. Tissue-resident natural killer cells in liver have been shown to display distinct markers and transcription factors as compared to thymic and conventional splenic NK cells [26]. ILC2s are dominant in lung especially in the collagen-rich regions but not in alveolar areas, where they induce eosinophilia through production of IL-5 and airway hyper-sensitivity through production of IL-13 [27]. ILC2s are found in significant proportion in small intestinal lamina propria where they mediate anti-helminth responses. ILC2s exist abundantly in skin and white adipose tissues [28]. Recently, gut ILC2s have been also shown to co-localize with cholinergic neurons and are responsive to the neuropeptide neuromedin U [29]. ILC3s are found in abundance in small intestinal lamina propria, intestinal cryptic areas and Payer’s patches (PPs) where they secrete IL-17 and IL-22 thereby providing immunity against intestinal pathogens and help maintain the integrity of the intestinal barrier [30]. ILC3s also reside within marginal zone areas of spleen, and orchestrate innate-like antibody production through secreting B-cell helper factors APRIL, BAFF, and signaling via CD40L [31]. Lymphoid tissue inducer cells play a significant role in fetal organogenesis of lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches [32].

Analysis of ILCs in humans and mice across different tissues revealed tissue-dependent heterogeneity in phenotype and number [33, 34]. The phenotype and function of ILCs can be modified by cues from the environment [29, 35]. For example, splenic retinoic acid-related orphan receptor gamma t (RORγt)+ ILC3s have distinct characteristics compared to ILC3s from small intestinal lamina propria. Splenic RORγt+ ILCs can suppress tumor growth, whereas intestinal RORγt+ ILCs fail to do so. Additionally, adoptive transfer experiments suggest that the transferred ILCs phenotypically and functionally adapt to the particular tissue where they settle, suggesting an important role of tissue environment in shaping functional specialization of ILCs [35]. Indeed, tissue specific factors and microbiota contribute greatly to the heterogeneity in the intestinal ILC subsets. Single cell transcriptomics analysis has identified multiple transcriptional states within the known gut ILC subsets under homeostatic conditions. Antibiotic treatment showed profound changes in ILC1 and ILC2-specific gene expression and chromatin landscapes [36]. Nutrient deficiency has also been shown to affect ILC subsets. Vitamin A deficiency leads to significant reduction in ILC3 numbers and increase in ILC2 numbers in the small intestine, imparting protection against intestinal helminths. This suggests ILCs act as a sensor for dietary stress and respond to the altered immunity at barrier surfaces [37]. Also, local tissue signals have been shown to play a crucial role in driving terminal differentiation of ILC2 and their T cell counterpart Th2 cells. Effector Th2 cells exhibit distinct chromatin accessibility from that of ILC2s at the Il4 and Arg1 loci but they acquire similar terminal effector functions when they are exposed to signals like IL-25, IL-33 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) [38].

Studies on parabiotic mice showed ILC-1, 2 and 3 are mainly tissue-resident cells that do not redistribute systemically over a period of 3 months. It is suggested that most ILCs residing in lung, salivary glands and small intestine are likely to be maintained and expanded locally under physiological or pathological conditions [39].

The possibilities to explain the abundance of ILCs in tissues are local production of ILCs versus recruitment of mature ILC or ILC-committed precursors. Recruited cells could comprise precursors and mature cells, and might differ between tissues. It will be interesting to understand for each tissue whether the local population of ILCs is largely established by settling in early fetal or neonatal life, or modified by ongoing migration in adult life from bone marrow to peripheral sites.

Central ILC progenitors and pathway(s) of central ILC differentiation

ILCs develop from fetal liver and adult bone-marrow hematopoietic progenitors, and populate peripheral tissues from mid to late stages of fetal development. Fetal ILC progenitors with LTi phenotype populate the intestine as early as embryonic day (E) 12.5-13.5, and support the development of lymphoid structures like Peyer’s patches via expression of lymphotoxins [40–42]. T-bet+, GATA-3+ and RORγt+ cells are detected in the fetal gut at E15.5, suggesting the presence of most ILC subsets by late fetal development [43, 44].

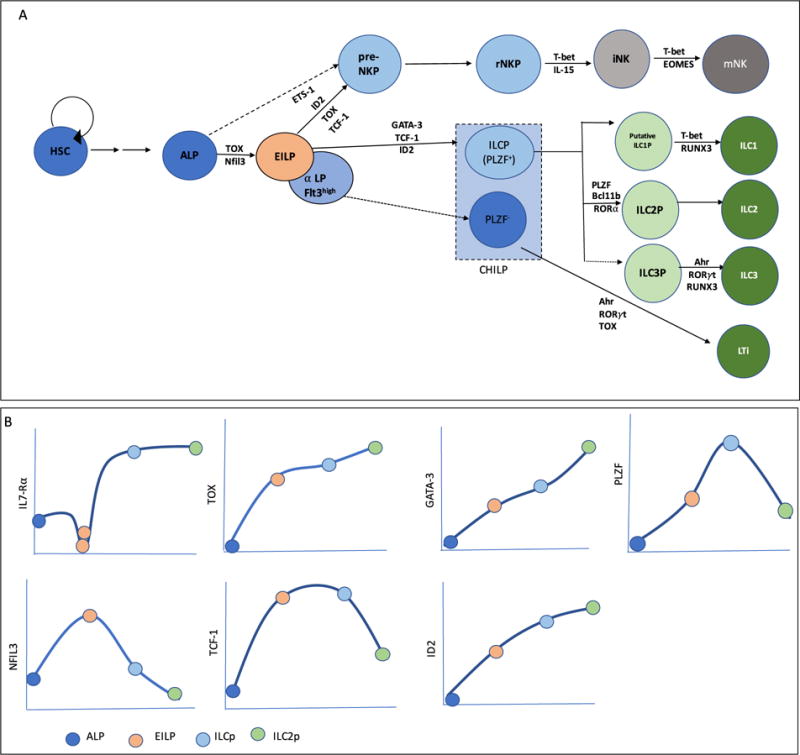

ILC progenitors are present in mouse adult bone marrow and mouse fetal liver (Figure 1A). All ILCs, like B cells and T cells, are now thought to arise from all lymphoid progenitors (ALP), which contain Ly6D− common lymphoid progenitors (CLP) and IL-7Rα expressing lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors (IL7Rα+ LMPP) [22, 41, 42, 45–50].Downstream of ALP, several ILC progenitors that might represent successive steps of ILC development are described. Reporter models for transcription factors expressed during early ILC development allowed the identification of ILC progenitors. Concomitantly, a common helper innate lymphoid cell progenitor (CHILP) characterized by its expression of Id2 (which encodes transcriptional repressor inhibitor of DNA binding 2, ID2), and an ILC precursor (ILCP) expressing high level of Zbtb16 (that encodes promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein, PLZF) were identified [51]. Both progenitors are phenotypically similar, expressing high level of IL-7Rα and low levels of Flt3. CHILPs can be divided into two fractions based on PLZF expression. PLZF+ CHILP correspond to ILCP and PLZF− CHILP include LTi progenitors [42].

Figure 1.

(A) Developmental stages in ILC lineage, along with the requirements for key transcription factors at each developmental transition. (B) The level of IL7-Rα and key transcription factors during the progressive stages of ILC development.

An early innate lymphoid progenitor (EILP) was later identified using a reporter mouse model for Tcf7 (which encodes T-cell factor-1, TCF-1) [52]. Most EILPs express lower levels of IL-7Rα, Thy1, Zbtb16 and Id2, and higher level of Flt3 as compared to ILCP, and have been shown to efficiently give rise to all mature ILC subsets as well as NK cells. An α4β7-expressing ALP called α-lymphoid progenitors (α-LP) was additionally proposed as the first uncommitted ILC progenitor [53]. α-LP are likely to be heterogeneous, with the ILC potential derived from a small population of Flt3hi EILP [53, 54]. ILC2P are found in fetal liver as well as in bone marrow [43, 55]. ILC2Ps are identified by their high expression of ST2, CD25 and GATA-3 [22, 55]. Bone marrow ILC2Ps have been shown to be downstream of CHILP [22].

Because ILC progenitors have been described by different laboratories using distinct mouse models, their developmental relationships have not always been examined. Recent work clarified the relationship between ALP, EILP and ILCP using short-term differentiation assays and phenotypic and transcriptional profiling of these three subsets by flow cytometry and RNA sequencing. Our studies indicate that EILP is a transitional population that is specified but not committed for innate cells lineages, linking multipotent ALP and innate cell lineage-committed ILCP [54]. Fate mapping using a Zbtb16-Cre mouse strain further shows that most helper ILC arise from a Zbtb16-expressing progenitor, likely the ILCP [51]. Functional specification toward each of the three ILC subsets has been reported by single cell transcriptomic analysis at the ILCP stage [42, 56]. Evidence exists for the presence of immature ILC1 cells or putative ILC1P in bone marrow and liver [22, 57]; however, whether an ILC3P exists in the bone marrow is still unclear.

NK cells develop in the bone marrow [58]. NK development progresses from ALP to a heterogeneous population of cells, NK progenitors (NKP), defined as Lin−CD122+NK1.1−DX5−, to immature NK (iNK) cells and then to mature NK (mNK) cells [59, 60]. More recent studies identified earlier NK lineage committed progenitors, the pre-NKP cells [61, 62], that differentiate into refined NKP (rNKP) cells. These pre-NKP and rNKP can generate mature NK cells both in vitro as well as in vivo [58, 61]. At this time, the relationship between ILC progenitors, NK progenitors and NK cells is not fully understood. Residual NK potential has been described for several ILC progenitors in vivo. Fate mapping using a Zbtb16-Cre mouse strain suggests that a small fraction of NK develop from an ILCP-like stage whereas most NK appear to develop through another pathway [52, 57]. One model for central ILC development suggests an early divergence between helper and NK cell lineages, prior to the ILCP stage (Figure 1A) [63], but see Ref [64]. However, it is unclear how and when this split occurs. Finally, it is unknown whether the preNKP and rNKP stage represent a major pathway of differentiation of NK, or if alternative pathways of NK differentiation exist.

Tissue-homing properties of central ILC progenitors

Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells have been identified in many extramedullary sites including spleen, muscle, liver, blood and other peripheral tissues [65–70]. It is possible that extramedullary hematopoiesis may make a significant contribution to ILC maintenance in tissues. The relative abundance of ILC subsets in tissues may depend on the migration of ILC progenitors from either fetal liver or bone marrow to peripheral tissues. Recent studies provide insight into early progenitors of ILC development that may seed peripheral tissues and initiate development of ILCs.

Molecules involved in migration and tissue homing such as CXCR5, CXCR6, CCR2, CD41, CD61, CD63 and CD226 are highly upregulated at the protein level at ILCP stage [24, 54, 56], suggesting that this progenitor possesses broad migratory properties toward various tissues, and might serve as an important substrate for in situ development of multiple lineages of tissues-resident ILCs. The importance of CXCR6 in migration of ILC progenitors has been established using Cxcr6−/− mice in which ILCP accumulation was observed in bone marrow whereas ILC numbers were significantly reduced in the periphery [71]. Consistently, multipotent ILC progenitors resembling ILCP have been described in various peripheral locations in humans and mice. Multipotent ILC progenitors are described in mouse fetal intestine [43]. ILC3P are identified in human tonsils and intestine as RORγt+ CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors with specified ILC3 lineage potential [72]. Another study identified an early precursor, CD34+CD117+CD45RA+ ILCPs, that are exclusively present in secondary lymphoid tissues and absent in bone marrow, cord and adult blood, suggesting these precursors may develop locally [73]. More recently, a Kit+ multipotent ILC progenitor identified in peripheral blood of human was proposed as a human ILCP [17]. Human ILCP were also found in various organs suggesting that these circulating Kit+ ILCP are able to home to tissues and give rise to mature ILC subsets. Differently from the mouse ILCP, this progenitor expressed low levels of PLZF [17]. However, the presence of H3K4Me2 marks in the vicinity of the Zbtb16 gene in human ILCP suggest that, similarly to mouse, PLZF is expressed during human ILC development. Additionally, human thymus and umbilical cord blood have been shown to contain CD5+ Id2-expressing ILCs capable of differentiating into all subsets of ILCs but not NK cells [74]. Upstream hematopoietic progenitors including HSCs have also been reported to seed peripheral tissues such as lung, and have been shown to be able to repopulate bone marrow under the conditions of stem cell deficiency in the bone marrow [75]. These studies together show that ILCP or closely related multipotent ILC progenitors settle in various peripheral tissues and might serve as an important substrate for in situ ILC development.

Other homing molecules are expressed from earlier stages of ILC development, suggesting that upstream progenitors might also be able to seed tissues. The adhesion molecule α4β7 is highly expressed from EILP stage and might play a key role in migration to intestine. CCR7, CCR9, CCR1, CX3CR1, CXCR4 and P-Selectin [54, 56, 76] are expressed from ALP stage onward and can help in the migration of these early progenitors to various tissues like liver, spleen, skin and other mucosal sites.

Apart from multipotent ILCP, lineage-restricted ILC precursors generated centrally might also migrate to specific tissues. ILC2P express CCR9 and low level of α4β7, which can facilitate migration to small intestine [55, 76]. IL-33 signaling was recently shown to support migration of ILC2s from bone marrow. Signaling via IL-33 downregulates CXCR4 expression, a chemokine that is required for retention of developing ILC2s in the bone marrow, and thus allows efficient egress of ILC2s from bone marrow to lung, skin, mesenteric lymph nodes and other peripheral tissues [77]. It is unknown whether ILC1P and ILC3P similarly develop centrally and migrate into tissues. RORγt+ hematopoietic progenitors are selectively enriched in human tonsils and intestinal lamina propria but absent from bone marrow, peripheral blood and thymus, and are capable of giving rise to ILC3. This suggests ILC3P might be generated in specific tissues such as tonsils and intestinal LP rather than centrally [44]. NK cells are thought to develop centrally, and to subsequently upregulate the gut homing molecule α4β7, skin homing molecule P-selectin ligand and LN homing molecule CD62L [78, 79].

Much remains to be understood regarding homing of early precursors of ILC. It is also unclear whether similar developmental pathways exist in the periphery as in bone marrow, or if alternate pathways underlie ILC development in peripheral tissues.

Differential requirements in central versus peripheral ILC development

Innate lymphoid cells are generated from ALPs under the influence of several transcription factors that are shared among multiple lineages like T cell or NK cells [80, 81](Figure 1A). These are involved in regulating and orchestrating the progressive stages of ILC development (Figure 1B). The requirement for distinct transcription factors at specific stages of central ILC development has been well documented [64]. It includes nuclear factor interleukin-3 (Nfil3) [82–86], TCF-1 [52, 87], thymocyte selection associated high-mobility group box (TOX) [88–90], ID2 [22, 44], GATA-binding protein 3 (GATA-3) [91] and PLZF [51]. Nfil3 and TOX are crucial transcription factors required for EILP development. GATA-3, TCF-1 and ID2 expression have been shown to be crucial prior to ILCP stage [52, 54]. ILC2P requires PLZF, Bcl11b, TCF-1, GATA-3 and ROR-α for development [80]. Nfil3, TOX, ETS1, ID2, TCF-1, BLIMP1, MEF, IRF2, EOMES and T-bet play essential role at different stages in NK development [87, 92, 93]. Nfil3, TOX and ETS1 have been shown to be important at early stages of NK development to induce the expression of various transcription factors like ID2 and T-bet that are needed for maturation of NK cells [94–96].

The requirement for most transcription factors during early central ILC development can generally be extended to the generation of peripheral ILC subsets, supporting that tissue-specific ILCs either originate from central ILC progenitors, or depend on a similar transcriptional network for their development. However, there are some puzzling exceptions. One puzzle in ILC development is that some transcription factors can appear critical for development of bone marrow ILC progenitors, but only mild defects are evident in ILCs at peripheral sites. For example, in Tcf7−/− mice, CHILP as well as pre-NKP and rNKP cells were nearly absent but many mature ILCs like ILC1, NK and NCR− ILC3 cells were present [97, 98]. One possible solution to this puzzle is that Tcf7 might be required for efficient development at early stages, but is not essential in mature ILCs. Hence proliferation at later stages of development might compensate for and mask early defects. Consistently, the requirement for factors like TCF-1 is more clearly evident in competitive bone marrow chimeras, where this sort of compensation is prevented. A related puzzle is that there appears to be a differential requirement for Nfil3 and TOX in central versus peripheral ILC development, possibly arguing against the notion that all ILCs are generated centrally. Tox-deficient mice almost completely lack central ILC progenitors as well as many mature ILC subsets [54, 88, 90]. However, the frequencies of mature ILC3 (NCR+ ILC3 and NCR− ILC3) remained intact in the gut [88]. Nfil3−/− mice show reduced NK cells in bone marrow, but NK cells from salivary gland were shown to be unaffected. These NK cells had higher expression of tissue resident markers like VLA1, CD103 and CD69. Thus, salivary gland NK cells are distinct from conventional NK [99]. Nfil3−/− mice have ILC1 cells in liver, skin, and uterus [100]. ILC1 [101] and ILC3 [102] have been described in uterus of Nfil3 −/− pregnant females. Non-NK ILC-like cells have been found to be intact in the thymus of Nfil3 −/− mice [103].

Cytokine signaling plays an important role in controlling differentiation of progenitors to mature ILC subsets in peripheral tissues [104]. IL-7 has been shown to be important for central ILC development. However, IL7R-independent ILC2 and ILC3 subsets are present in small intestinal lamina propria, and are fully functional as they can confer protection to IL7Rα−/− mice against C. rodentium infection. Thus, it is interesting to note that the IL-7 requirement is different for ILC2 and ILC3 subsets in bone marrow versus gut [105].

These studies indicate that specific lineages of tissue resident ILCs can develop in the apparent absence of central ILC progenitors, suggesting they may arise in situ. Why transcription factors such as TOX and Nfil3 would be differentially required for ILC development in distinct environments remains to be understood. One possibility is that fetal and adult ILC development requires distinct transcription factors. Seeding of fetal progenitors in peripheral tissues could result in long-term maintenance of tissue resident ILCs. Alternatively, signals uniquely present in tissues may enable development or proliferation of some residual cells that develop from alternative pathways even when transcription factors like TOX are absent, through the expression of other transcription factors that might be redundant; the absence of such signals at central sites may prevent this type of compensation. In either case, it appears that there is differential requirement of transcription factors and cytokines to dictate the developmental programs of cells present in adult bone marrow and tissues.

Conclusion

Recent advances in the ILC field suggest the diversity of ILCs is greater than previously appreciated. Early progenitors of ILC development are identified in fetal liver and bone marrow, but how ILCs are maintained at steady state and in conditions of inflammation needs further study. Early ILC progenitors and mature ILCs highly express tissue homing molecules, suggesting migration to tissues is important for ILC. Yet many questions remain unanswered. How are frequencies and numbers of different types of ILC maintained in different tissues? Do specified ILC precursors home to distinct tissues and settle there to become mature ILCs? Are the transcriptional and cytokine requirements different between central versus peripheral ILC generation? What are the tissue-specific factors that shape local ILC distribution? Do extramedullary sites of ILC production exist? Answers to these questions will help us understand how ILC play their essential immune function.

Highlights.

Tissue homing properties of ILC progenitors and mature ILC.

Differential requirements between central and peripheral ILC development.

Peripheral generation and maintenance of ILC.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research at the National Cancer Institute.

Abbreviations

- ILC

Innate lymphoid cell

- LTi

Lymphoid tissue inducer

- NK

Natural killer

- ALP

All lymphoid progenitor

- LMPP

Lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitor

- CLP

Common lymphoid progenitors

- CHILP

Common helper innate lymphoid cell progenitor

- ILCP

ILC progenitor

- EILP

Early innate lymphoid progenitor

- α-LP

Alpha-lymphoid progenitor

- NKP

NK progenitor

Biography

Arundhoti Das obtained her Ph.D. degree from National Institute of Immunology, New Delhi, India in 2016, with Dr. Vineeta Bal. Currently, she is a postdoctoral fellow working with Avinash Bhandoola in the T Cell Biology and Development Unit, Laboratory of Genome Integrity, National Cancer Institute, USA. Website at: https://ccr.cancer.gov/Laboratory-of-Genome-Integrity/avinash-bhandoola

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not state any conflict of interest.

Bibliography

- 1.Spits H, Artis D, Colonna M, Diefenbach A, Di Santo JP, Eberl G, Koyasu S, Locksley RM, McKenzie AN, Mebius RE, Powrie F, Vivier E. Innate lymphoid cells–a proposal for uniform nomenclature. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(2):145–9. doi: 10.1038/nri3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang Y, Guo L, Qiu J, Chen X, Hu-Li J, Siebenlist U, Williamson PR, Urban JF, Jr, Paul WE. IL-25-responsive, lineage-negative KLRG1(hi) cells are multipotential ‘inflammatory’ type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(2):161–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang K, Xu X, Pasha MA, Siebel CW, Costello A, Haczku A, MacNamara K, Liang T, Zhu J, Bhandoola A, Maillard I, Yang Q. Cutting Edge: Notch Signaling Promotes the Plasticity of Group-2 Innate Lymphoid Cells. J Immunol. 2017;198(5):1798–1803. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gronke K, Kofoed-Nielsen M, Diefenbach A. Innate lymphoid cells, precursors and plasticity. Immunol Lett. 2016;179:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohne Y, Silver JS, Thompson-Snipes L, Collet MA, Blanck JP, Cantarel BL, Copenhaver AM, Humbles AA, Liu YJ. IL-1 is a critical regulator of group 2 innate lymphoid cell function and plasticity. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(6):646–55. doi: 10.1038/ni.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silver JS, Kearley J, Copenhaver AM, Sanden C, Mori M, Yu L, Pritchard GH, Berlin AA, Hunter CA, Bowler R, Erjefalt JS, Kolbeck R, Humbles AA. Inflammatory triggers associated with exacerbations of COPD orchestrate plasticity of group 2 innate lymphoid cells in the lungs. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(6):626–35. doi: 10.1038/ni.3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rankin LC, Groom JR, Chopin M, Herold MJ, Walker JA, Mielke LA, McKenzie AN, Carotta S, Nutt SL, Belz GT. The transcription factor T-bet is essential for the development of NKp46+ innate lymphocytes via the Notch pathway. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(4):389–95. doi: 10.1038/ni.2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klose CS, Kiss EA, Schwierzeck V, Ebert K, Hoyler T, d’Hargues Y, Goppert N, Croxford AL, Waisman A, Tanriver Y, Diefenbach A. A T-bet gradient controls the fate and function of CCR6-RORgammat+ innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2013;494(7436):261–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klose CS, Artis D. Innate lymphoid cells as regulators of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(7):765–74. doi: 10.1038/ni.3489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spits H, Di Santo JP. The expanding family of innate lymphoid cells: regulators and effectors of immunity and tissue remodeling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(1):21–7. doi: 10.1038/ni.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eberl G, Colonna M, Di Santo JP, McKenzie AN. Innate lymphoid cells. Innate lymphoid cells: a new paradigm in immunology. Science. 2015;348(6237):879–88. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa6566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker JA, Barlow JL, McKenzie AN. Innate lymphoid cells–how did we miss them? Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(2):75–87. doi: 10.1038/nri3349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paust S, Gill HS, Wang BZ, Flynn MP, Moseman EA, Senman B, Szczepanik M, Telenti A, Askenase PW, Compans RW, von Andrian UH. Critical role for the chemokine receptor CXCR6 in NK cell-mediated antigen-specific memory of haptens and viruses. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(12):1127–35. doi: 10.1038/ni.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez-Gonzalez I, Matha L, Steer CA, Ghaedi M, Poon GF, Takei F. Allergen-Experienced Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells Acquire Memory-like Properties and Enhance Allergic Lung Inflammation. Immunity. 2016;45(1):198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan X, Rudensky AY. Hallmarks of Tissue-Resident Lymphocytes. Cell. 2016;164(6):1198–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zook EC, Kee BL. Development of innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(7):775–82. doi: 10.1038/ni.3481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim AI, Li Y, Lopez-Lastra S, Stadhouders R, Paul F, Casrouge A, Serafini N, Puel A, Bustamante J, Surace L, Masse-Ranson G, David E, Strick-Marchand H, Le Bourhis L, Cocchi R, Topazio D, Graziano P, Muscarella LA, Rogge L, Norel X, Sallenave JM, Allez M, Graf T, Hendriks RW, Casanova JL, Amit I, Yssel H, Di Santo JP. Systemic Human ILC Precursors Provide a Substrate for Tissue ILC Differentiation. Cell. 2017;168(6):1086–1100 e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spits H, Cupedo T. Innate lymphoid cells: emerging insights in development, lineage relationships, and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:647–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinette ML, Colonna M. Immune modules shared by innate lymphoid cells and T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(5):1243–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim AI, Verrier T, Vosshenrich CA, Di Santo JP. Developmental options and functional plasticity of innate lymphoid cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2017;44:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diefenbach A, Colonna M, Koyasu S. Development, differentiation, and diversity of innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2014;41(3):354–365. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klose CS, Flach M, Mohle L, Rogell L, Hoyler T, Ebert K, Fabiunke C, Pfeifer D, Sexl V, Fonseca-Pereira D, Domingues RG, Veiga-Fernandes H, Arnold SJ, Busslinger M, Dunay IR, Tanriver Y, Diefenbach A. Differentiation of Type 1 ILCs from a Common Progenitor to All Helper-like Innate Lymphoid Cell Lineages. Cell. 2014;157(2):340–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abt MC, Lewis BB, Caballero S, Xiong H, Carter RA, Susac B, Ling L, Leiner I, Pamer EG. Innate Immune Defenses Mediated by Two ILC Subsets Are Critical for Protection against Acute Clostridium difficile Infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;18(1):27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim CH, Hashimoto-Hill S, Kim M. Migration and Tissue Tropism of Innate Lymphoid Cells. Trends Immunol. 2016;37(1):68–79. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cortez VS, Robinette ML, Colonna M. Innate lymphoid cells: new insights into function and development. Curr Opin Immunol. 2015;32:71–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeang HXAw, Piersma SJ, Lin Y, Yang L, Malkova ON, Miner C, Krupnick AS, Chapman WC, Yokoyama WM. Cutting Edge: Human CD49e- NK Cells Are Tissue Resident in the Liver. J Immunol. 2017;198(4):1417–1422. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nussbaum JC, Van Dyken SJ, von Moltke J, Cheng LE, Mohapatra A, Molofsky AB, Thornton EE, Krummel MF, Chawla A, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells control eosinophil homeostasis. Nature. 2013;502(7470):245–8. doi: 10.1038/nature12526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neill DR, Flynn RJ. Origins and evolution of innate lymphoid cells: Wardens of barrier immunity. Parasite Immunol. 2017 doi: 10.1111/pim.12436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klose CSN, Mahlakoiv T, Moeller JB, Rankin LC, Flamar AL, Kabata H, Monticelli LA, Moriyama S, Putzel GG, Rakhilin N, Shen X, Kostenis E, Konig GM, Senda T, Carpenter D, Farber DL, Artis D. The neuropeptide neuromedin U stimulates innate lymphoid cells and type 2 inflammation. Nature. 2017;549(7671):282–286. doi: 10.1038/nature23676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melo-Gonzalez F, Hepworth MR. Functional and phenotypic heterogeneity of group 3 innate lymphoid cells. Immunology. 2017;150(3):265–275. doi: 10.1111/imm.12697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magri G, Miyajima M, Bascones S, Mortha A, Puga I, Cassis L, Barra CM, Comerma L, Chudnovskiy A, Gentile M, Llige D, Cols M, Serrano S, Arostegui JI, Juan M, Yague J, Merad M, Fagarasan S, Cerutti A. Innate lymphoid cells integrate stromal and immunological signals to enhance antibody production by splenic marginal zone B cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(4):354–364. doi: 10.1038/ni.2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finke D. Fate and function of lymphoid tissue inducer cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17(2):144–50. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simoni Y, Fehlings M, Kloverpris HN, McGovern N, Koo SL, Loh CY, Lim S, Kurioka A, Fergusson JR, Tang CL, Kam MH, Dennis K, Lim TKH, Fui ACY, Hoong CW, Chan JKY, Curotto de Lafaille M, Narayanan S, Baig S, Shabeer M, Toh SES, Tan HKK, Anicete R, Tan EH, Takano A, Klenerman P, Leslie A, Tan DSW, Tan IB, Ginhoux F, Newell EW. Human Innate Lymphoid Cell Subsets Possess Tissue-Type Based Heterogeneity in Phenotype and Frequency. Immunity. 2017;46(1):148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinette ML, Fuchs A, Cortez VS, Lee JS, Wang Y, Durum SK, Gilfillan S, Colonna M, C. Immunological Genome Transcriptional programs define molecular characteristics of innate lymphoid cell classes and subsets. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(3):306–17. doi: 10.1038/ni.3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nussbaum K, Burkhard SH, Ohs I, Mair F, Klose CSN, Arnold SJ, Diefenbach A, Tugues S, Becher B. Tissue microenvironment dictates the fate and tumor-suppressive function of type 3 ILCs. J Exp Med. 2017;214(8):2331–2347. doi: 10.1084/jem.20162031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gury-BenAri M, Thaiss CA, Serafini N, Winter DR, Giladi A, Lara-Astiaso D, Levy M, Salame TM, Weiner A, David E, Shapiro H, Dori-Bachash M, Pevsner-Fischer M, Lorenzo-Vivas E, Keren-Shaul H, Paul F, Harmelin A, Eberl G, Itzkovitz S, Tanay A, Santo JPDi, Elinav E, Amit I. The Spectrum and Regulatory Landscape of Intestinal Innate Lymphoid Cells Are Shaped by the Microbiome. Cell. 2016;166(5):1231–1246 e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spencer SP, Wilhelm C, Yang Q, Hall JA, Bouladoux N, Boyd A, Nutman TB, Urban JF, Jr, Wang J, Ramalingam TR, Bhandoola A, Wynn TA, Belkaid Y. Adaptation of innate lymphoid cells to a micronutrient deficiency promotes type 2 barrier immunity. Science. 2014;343(6169):432–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1247606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Dyken SJ, Nussbaum JC, Lee J, Molofsky AB, Liang HE, Pollack JL, Gate RE, Haliburton GE, Ye CJ, Marson A, Erle DJ, Locksley RM. A tissue checkpoint regulates type 2 immunity. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(12):1381–1387. doi: 10.1038/ni.3582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gasteiger G, Fan X, Dikiy S, Lee SY, Rudensky AY. Tissue residency of innate lymphoid cells in lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs. Science. 2015;350(6263):981–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aac9593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cherrier M, Eberl G. The development of LTi cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24(2):178–83. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Possot C, Schmutz S, Chea S, Boucontet L, Louise A, Cumano A, Golub R. Notch signaling is necessary for adult, but not fetal, development of RORgammat(+) innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(10):949–58. doi: 10.1038/ni.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishizuka IE, Chea S, Gudjonson H, Constantinides MG, Dinner AR, Bendelac A, Golub R. Single-cell analysis defines the divergence between the innate lymphoid cell lineage and lymphoid tissue-inducer cell lineage. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(3):269–76. doi: 10.1038/ni.3344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bando JK, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Identification and distribution of developing innate lymphoid cells in the fetal mouse intestine. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(2):153–60. doi: 10.1038/ni.3057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chea S, Schmutz S, Berthault C, Perchet T, Petit M, Burlen-Defranoux O, Goldrath AW, Rodewald HR, Cumano A, Golub R. Single-Cell Gene Expression Analyses Reveal Heterogeneous Responsiveness of Fetal Innate Lymphoid Progenitors to Notch Signaling. Cell Rep. 2016;14(6):1500–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cherrier M, Sawa S, Eberl G. Notch, Id2, and RORgammat sequentially orchestrate the fetal development of lymphoid tissue inducer cells. J Exp Med. 2012;209(4):729–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oguro H, Ding L, Morrison SJ. SLAM family markers resolve functionally distinct subpopulations of hematopoietic stem cells and multipotent progenitors. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13(1):102–16. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moro K, Yamada T, Tanabe M, Takeuchi T, Ikawa T, Kawamoto H, Furusawa J, Ohtani M, Fujii H, Koyasu S. Innate production of T(H)2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit(+)Sca-1(+) lymphoid cells. Nature. 2010;463(7280):540–4. doi: 10.1038/nature08636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghaedi M, Steer CA, Martinez-Gonzalez I, Halim TY, Abraham N, Takei F. Common-Lymphoid-Progenitor-Independent Pathways of Innate and T Lymphocyte Development. Cell Rep. 2016;15(3):471–80. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang Q, Saenz SA, Zlotoff DA, Artis D, Bhandoola A. Cutting edge: Natural helper cells derive from lymphoid progenitors. J Immunol. 2011;187(11):5505–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Inlay MA, Bhattacharya D, Sahoo D, Serwold T, Seita J, Karsunky H, Plevritis SK, Dill DL, Weissman IL. Ly6d marks the earliest stage of B-cell specification and identifies the branchpoint between B-cell and T-cell development. Genes Dev. 2009;23(20):2376–81. doi: 10.1101/gad.1836009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Constantinides MG, McDonald BD, Verhoef PA, Bendelac A. A committed precursor to innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2014;508(7496):397–401. doi: 10.1038/nature13047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang Q, Li F, Harly C, Xing S, Ye L, Xia X, Wang H, Wang X, Yu S, Zhou X, Cam M, Xue HH, Bhandoola A. TCF-1 upregulation identifies early innate lymphoid progenitors in the bone marrow. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(10):1044–50. doi: 10.1038/ni.3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seillet C, Mielke LA, Amann-Zalcenstein DB, Su S, Gao J, Almeida FF, Shi W, Ritchie ME, Naik SH, Huntington ND, Carotta S, Belz GT. Deciphering the Innate Lymphoid Cell Transcriptional Program. Cell Rep. 2016;17(2):436–447. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harly C, Cam M, Kaye J, Bhandoola A. Development and differentiation of early innate lymphoid progenitors. J Exp Med. 2017 doi: 10.1084/jem.20170832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoyler T, Klose CS, Souabni A, Turqueti-Neves A, Pfeifer D, Rawlins EL, Voehringer D, Busslinger M, Diefenbach A. The transcription factor GATA-3 controls cell fate and maintenance of type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2012;37(4):634–48. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu Y, Tsang JC, Wang C, Clare S, Wang J, Chen X, Brandt C, Kane L, Campos LS, Lu L, Belz GT, McKenzie AN, Teichmann SA, Dougan G, Liu P. Single-cell RNA-seq identifies a PD-1hi ILC progenitor and defines its development pathway. Nature. 2016;539(7627):102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature20105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Constantinides MG, Gudjonson H, McDonald BD, Ishizuka IE, Verhoef PA, Dinner AR, Bendelac A. PLZF expression maps the early stages of ILC1 lineage development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(16):5123–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423244112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goh W, Huntington ND. Regulation of Murine Natural Killer Cell Development. Front Immunol. 2017;8:130. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosmaraki EE, Douagi I, Roth C, Colucci F, Cumano A, Di Santo JP. Identification of committed NK cell progenitors in adult murine bone marrow. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31(6):1900–9. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200106)31:6<1900::aid-immu1900>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kondo M, Weissman IL, Akashi K. Identification of clonogenic common lymphoid progenitors in mouse bone marrow. Cell. 1997;91(5):661–72. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fathman JW, Bhattacharya D, Inlay MA, Seita J, Karsunky H, Weissman IL. Identification of the earliest natural killer cell-committed progenitor in murine bone marrow. Blood. 2011;118(20):5439–47. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carotta S, Pang SH, Nutt SL, Belz GT. Identification of the earliest NK-cell precursor in the mouse BM. Blood. 2011;117(20):5449–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-318956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang Q, Bhandoola A. The development of adult innate lymphoid cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2016;39:114–20. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Serafini N, Vosshenrich CA, Di Santo JP. Transcriptional regulation of innate lymphoid cell fate. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(7):415–28. doi: 10.1038/nri3855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Massberg S, Schaerli P, Knezevic-Maramica I, Kollnberger M, Tubo N, Moseman EA, Huff IV, Junt T, Wagers AJ, Mazo IB, von Andrian UH. Immunosurveillance by hematopoietic progenitor cells trafficking through blood, lymph, and peripheral tissues. Cell. 2007;131(5):994–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cardier JE, Barbera-Guillem E. Extramedullary hematopoiesis in the adult mouse liver is associated with specific hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells. Hepatology. 1997;26(1):165–75. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wright DE, Wagers AJ, Gulati AP, Johnson FL, Weissman IL. Physiological migration of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Science. 2001;294(5548):1933–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1064081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saenz SA, Siracusa MC, Monticelli LA, Ziegler CG, Kim BS, Brestoff JR, Peterson LW, Wherry EJ, Goldrath AW, Bhandoola A, Artis D. IL-25 simultaneously elicits distinct populations of innate lymphoid cells and multipotent progenitor type 2 (MPPtype2) cells. J Exp Med. 2013;210(9):1823–37. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Griseri T, McKenzie BS, Schiering C, Powrie F. Dysregulated hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell activity promotes interleukin-23-driven chronic intestinal inflammation. Immunity. 2012;37(6):1116–29. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Siracusa MC, Saenz SA, Wojno ED, Kim BS, Osborne LC, Ziegler CG, Benitez AJ, Ruymann KR, Farber DL, Sleiman PM, Hakonarson H, Cianferoni A, Wang ML, Spergel JM, Comeau MR, Artis D. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin-mediated extramedullary hematopoiesis promotes allergic inflammation. Immunity. 2013;39(6):1158–70. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chea S, Possot C, Perchet T, Petit M, Cumano A, Golub R. CXCR6 Expression Is Important for Retention and Circulation of ILC Precursors. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:368427. doi: 10.1155/2015/368427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Montaldo E, Teixeira-Alves LG, Glatzer T, Durek P, Stervbo U, Hamann W, Babic M, Paclik D, Stolzel K, Grone J, Lozza L, Juelke K, Matzmohr N, Loiacono F, Petronelli F, Huntington ND, Moretta L, Mingari MC, Romagnani C. Human RORgammat(+)CD34(+) cells are lineage-specified progenitors of group 3 RORgammat(+) innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2014;41(6):988–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Scoville SD, Mundy-Bosse BL, Zhang MH, Chen L, Zhang X, Keller KA, Hughes T, Chen L, Cheng S, Bergin SM, Mao HC, McClory S, Yu J, Carson WE, 3rd, Caligiuri MA, Freud AG. A Progenitor Cell Expressing Transcription Factor RORgammat Generates All Human Innate Lymphoid Cell Subsets. Immunity. 2016;44(5):1140–50. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nagasawa M, Germar K, Blom B, Spits H. Human CD5(+) Innate Lymphoid Cells Are Functionally Immature and Their Development from CD34(+) Progenitor Cells Is Regulated by Id2. Front Immunol. 2017;8 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lefrancais E, Ortiz-Munoz G, Caudrillier A, Mallavia B, Liu F, Sayah DM, Thornton EE, Headley MB, David T, Coughlin SR, Krummel MF, Leavitt AD, Passegue E, Looney MR. The lung is a site of platelet biogenesis and a reservoir for haematopoietic progenitors. Nature. 2017;544(7648):105–109. doi: 10.1038/nature21706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim MH, Taparowsky EJ, Kim CH. Retinoic Acid Differentially Regulates the Migration of Innate Lymphoid Cell Subsets to the Gut. Immunity. 2015;43(1):107–19. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stier MT, Zhang J, Goleniewska K, Cephus JY, Rusznak M, Wu L, Van Kaer L, Zhou B, Newcomb DC, Peebles RS., Jr IL-33 promotes the egress of group 2 innate lymphoid cells from the bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2017 doi: 10.1084/jem.20170449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Morris MA, Ley K. Trafficking of natural killer cells. Curr Mol Med. 2004;4(4):431–8. doi: 10.2174/1566524043360609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Olson JA, Zeiser R, Beilhack A, Goldman JJ, Negrin RS. Tissue-specific homing and expansion of donor NK cells in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J Immunol. 2009;183(5):3219–28. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhong C, Zhu J. Transcriptional Regulatory Network for the Development of Innate Lymphoid Cells. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/264502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.De Obaldia ME, Bhandoola A. Transcriptional regulation of innate and adaptive lymphocyte lineages. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33:607–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yu X, Wang Y, Deng M, Li Y, Ruhn KA, Zhang CC, Hooper LV. The basic leucine zipper transcription factor NFIL3 directs the development of a common innate lymphoid cell precursor. Elife. 2014;3 doi: 10.7554/eLife.04406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xu W, Domingues RG, Fonseca-Pereira D, Ferreira M, Ribeiro H, Lopez-Lastra S, Motomura Y, Moreira-Santos L, Bihl F, Braud V, Kee B, Brady H, Coles MC, Vosshenrich C, Kubo M, Di Santo JP, Veiga-Fernandes H. NFIL3 orchestrates the emergence of common helper innate lymphoid cell precursors. Cell Rep. 2015;10(12):2043–54. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Seillet C, Huntington ND, Gangatirkar P, Axelsson E, Minnich M, Brady HJ, Busslinger M, Smyth MJ, Belz GT, Carotta S. Differential requirement for Nfil3 during NK cell development. J Immunol. 2014;192(6):2667–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kamizono S, Duncan GS, Seidel MG, Morimoto A, Hamada K, Grosveld G, Akashi K, Lind EF, Haight JP, Ohashi PS, Look AT, Mak TW. Nfil3/E4bp4 is required for the development and maturation of NK cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2009;206(13):2977–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Geiger TL, Abt MC, Gasteiger G, Firth MA, O’Connor MH, Geary CD, O’Sullivan TE, Brink MRvanden, Pamer EG, Hanash AM, Sun JC. Nfil3 is crucial for development of innate lymphoid cells and host protection against intestinal pathogens. J Exp Med. 2014;211(9):1723–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jeevan-Raj B, Gehrig J, Charmoy M, Chennupati V, Grandclement C, Angelino P, Delorenzi M, Held W. The Transcription Factor Tcf1 Contributes to Normal NK Cell Development and Function by Limiting the Expression of Granzymes. Cell Rep. 2017;20(3):613–626. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Seehus CR, Aliahmad P, de la Torre B, Iliev ID, Spurka L, Funari VA, Kaye J. The development of innate lymphoid cells requires TOX-dependent generation of a common innate lymphoid cell progenitor. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(6):599–608. doi: 10.1038/ni.3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Aliahmad P, Seksenyan A, Kaye J. The many roles of TOX in the immune system. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24(2):173–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Aliahmad P, de la Torre B, Kaye J. Shared dependence on the DNA-binding factor TOX for the development of lymphoid tissue-inducer cell and NK cell lineages. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(10):945–52. doi: 10.1038/ni.1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yagi R, Zhong C, Northrup DL, Yu F, Bouladoux N, Spencer S, Hu G, Barron L, Sharma S, Nakayama T, Belkaid Y, Zhao K, Zhu J. The transcription factor GATA3 is critical for the development of all IL-7Ralpha-expressing innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2014;40(3):378–88. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yokota Y, Mansouri A, Mori S, Sugawara S, Adachi S, Nishikawa S, Gruss P. Development of peripheral lymphoid organs and natural killer cells depends on the helix-loop-helix inhibitor Id2. Nature. 1999;397(6721):702–6. doi: 10.1038/17812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Luevano M, Madrigal A, Saudemont A. Transcription factors involved in the regulation of natural killer cell development and function: an update. Front Immunol. 2012;3:319. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Huntington ND, Nutt SL, Carotta S. Regulation of murine natural killer cell commitment. Front Immunol. 2013;4:14. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Simonetta F, Pradier A, Roosnek E. T-bet and Eomesodermin in NK Cell Development, Maturation, and Function. Front Immunol. 2016;7:241. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ramirez K, Chandler KJ, Spaulding C, Zandi S, Sigvardsson M, Graves BJ, Kee BL. Gene deregulation and chronic activation in natural killer cells deficient in the transcription factor ETS1. Immunity. 2012;36(6):921–32. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yang Q, Monticelli LA, Saenz SA, Chi AW, Sonnenberg GF, Tang J, De Obaldia ME, Bailis W, Bryson JL, Toscano K, Huang J, Haczku A, Pear WS, Artis D, Bhandoola A. T cell factor 1 is required for group 2 innate lymphoid cell generation. Immunity. 2013;38(4):694–704. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mielke LA, Groom JR, Rankin LC, Seillet C, Masson F, Putoczki T, Belz GT. TCF-1 controls ILC2 and NKp46+RORgammat+ innate lymphocyte differentiation and protection in intestinal inflammation. J Immunol. 2013;191(8):4383–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cortez VS, Fuchs A, Cella M, Gilfillan S, Colonna M. Cutting edge: Salivary gland NK cells develop independently of Nfil3 in steady-state. J Immunol. 2014;192(10):4487–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sojka DK, Plougastel-Douglas B, Yang L, Pak-Wittel MA, Artyomov MN, Ivanova Y, Zhong C, Chase JM, Rothman PB, Yu J, Riley JK, Zhu J, Tian Z, Yokoyama WM. Tissue-resident natural killer (NK) cells are cell lineages distinct from thymic and conventional splenic NK cells. Elife. 2014;3:e01659. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Boulenouar S, Doisne JM, Sferruzzi-Perri A, Gaynor LM, Kieckbusch J, Balmas E, Yung HW, Javadzadeh S, Volmer L, Hawkes DA, Phillips K, Brady HJ, Fowden AL, Burton GJ, Moffett A, Colucci F. The Residual Innate Lymphoid Cells in NFIL3-Deficient Mice Support Suboptimal Maternal Adaptations to Pregnancy. Front Immunol. 2016;7:43. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Doisne JM, Balmas E, Boulenouar S, Gaynor LM, Kieckbusch J, Gardner L, Hawkes DA, Barbara CF, Sharkey AM, Brady HJ, Brosens JJ, Moffett A, Colucci F. Composition, Development, and Function of Uterine Innate Lymphoid Cells. J Immunol. 2015;195(8):3937–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gabrielli S, Sun M, Bell A, Zook EC, de Pooter RF, Zamai L, Kee BL. Murine thymic NK cells are distinct from ILC1s and have unique transcription factor requirements. Eur J Immunol. 2017;47(5):800–805. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Seillet C, Belz GT, Mielke LA. Complexity of cytokine network regulation of innate lymphoid cells in protective immunity. Cytokine. 2014;70(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Robinette ML, Bando JK, Song W, Ulland TK, Gilfillan S, Colonna M. IL-15 sustains IL-7R-independent ILC2 and ILC3 development. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14601. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]