Abstract

Here we identify hundreds of new drug-disease associations for over 900 FDA-approved drugs by quantifying the network proximity of disease genes and drug targets in the human (protein–protein) interactome. We select four network-predicted associations to test their causal relationship using large healthcare databases with over 220 million patients and state-of-the-art pharmacoepidemiologic analyses. Using propensity score matching, two of four network-based predictions are validated in patient-level data: carbamazepine is associated with an increased risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) [hazard ratio (HR) 1.56, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.12–2.18], and hydroxychloroquine is associated with a decreased risk of CAD (HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.59–0.97). In vitro experiments show that hydroxychloroquine attenuates pro-inflammatory cytokine-mediated activation in human aortic endothelial cells, supporting mechanistically its potential beneficial effect in CAD. In summary, we demonstrate that a unique integration of protein-protein interaction network proximity and large-scale patient-level longitudinal data complemented by mechanistic in vitro studies can facilitate drug repurposing.

Repurposing approved drugs could accelerate treatment options for various diseases. Here, the authors use network proximity of disease gene products and drug targets in the human protein interactome to identify drug-disease associations for cardiovascular disease, and validate these using longitudinal healthcare data.

Introduction

Although investment in biomedical and pharmaceutical research and development has increased significantly over the past 20 years, the annual number of new treatments approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not significantly increased1. Among the reasons for this shortcoming in contemporary drug development are a lack of well-established predictive pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics approaches, and concerning safety and tolerability profiles for new chemical entities from preclinical studies to clinical trials2. In addition to these well recognized explanations, another important factor limiting more effective drug development may be continued adherence to the classical (one gene, one drug, one disease) hypothesis. Focusing on just single targets results in failure to anticipate off-target toxicity, unintended beneficial effects, or multiple target interactions leading to suboptimal efficacy3,4. Without full knowledge of the broader network context of the molecular determinants of disease and drug targets in the protein–protein interaction network (human interactome), investigators cannot develop meaningful approaches for efficacious treatment of complex diseases5.

Novel approaches, such as network-based drug-disease proximity, that shed light on the relationship between drugs (drug targets) and diseases [molecular (protein) determinants in disease modules]6–8 can serve as a useful tool for efficient screening of potentially new indications for approved drugs with well-established pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, safety and tolerability profiles, or previously unidentified adverse events9–12. However, in order to prioritize the repurposed candidates or suggest novel interventions based on drug-disease associations identified by network-based approaches, rigorous validation is mandatory. Since network-based drug repurposing focuses on drugs that are already approved and are used in clinical practice, such hypothesis testing is possible using large-scale patient-level data collected during routine healthcare. Such data are regularly used to generate actionable evidence regarding effectiveness, harm, use, and value of medications to supplement evidence generated in randomized controlled trials; these trials that lead to drug approval are typically limited in scope owing to a relatively modest study sample size, comparatively short follow-up time, and frequent underrepresentation of the most relevant populations13. The unique strengths of routine healthcare data that make them ideal for validating hypotheses generated by network-based predictions include their provision of large patient populations useful for detecting small differences, and the availability of a large number of patient factors recorded without any recall bias, including demographics, comorbid conditions, and medication use, that allow for high-dimensional covariate adjustment to minimize confounding14–16.

In this study, we developed a systems pharmacology-based platform that quantifies the interplay between disease proteins and drug targets in the human protein–protein interactome with state-of-the-art pharmacoepidemiologic methods for hypothesis validation using longitudinal data with over 220 million patients. We followed this analysis with in vitro assays to test potential drug mechanisms. As proof of the utility of the overall approach, we focused on cardiovascular (CV) outcomes given their high prevalence in the population, as an exemplary set of diseases with which to identify associations between drugs used for non-cardiac indications and CV outcomes. We demonstrate that an integrated approach incorporating network proximity together with large-scale patient longitudinal data and in vitro experimental assays offers an effective platform by which to identify and validate novel associations that can be used to minimize unanticipated adverse drug effects and optimize drug repurposing. These results suggest that this integrative approach can be generalized to other drugs/disease combinations.

Results

An atlas of drug effects via network proximity

Our previous studies have demonstrated that disease gene products (proteins) are likely to cluster in the same network neighborhood or disease module within the human protein–protein interactome6,17,18. Drug targets representing nodes within molecular networks are often intrinsically coupled in both therapeutic and adverse effects. We, therefore, proposed that for a drug with multiple targets to be on-target effective for a disease or to cause off-target adverse effects (Supplementary Fig. 1a), its target proteins should be within or in the immediate vicinity of the corresponding disease module in the human interactome8,10. We chose CV diseases as a test case of this principle due to their prevalence in the population and their high morbidity and mortality. To examine drug effects on CV diseases, we used a network proximity measure that quantifies the relationship between CV-specific disease modules and drug targets in the human protein–protein interaction (PPI) network (Supplementary Fig. 1b). To improve the data quality of the human interactome, we used only five types of experimental data: (a) binary PPIs obtained using systematic, unbiased, high-throughput yeast-two-hybrid (Y2H) systems19; (b) kinase-substrate interactions from literature-derived low-throughput and high-throughput experiments; (c) binary PPIs from three-dimensional (3D) protein structures; (d) signaling networks from literature-derived low-throughput experiments; and (e) literature-curated PPIs identified by affinity purification followed by mass spectrometry (AP-MS), Y2H, and/or literature-derived low-throughput experiments in which every interaction is supported by multiple sources of experimental evidence (Methods section). The updated human interactome defined in this way includes 243,603 PPIs connecting 16,677 unique proteins (Supplementary Data 1). We also compiled 984 FDA-approved drugs by pooling the reported experimental drug-target binding affinity data: median effective concentration (EC50), median inhibitory concentration (IC50), inhibition constant/potency (Ki), or dissociation constant (Kd), each ≤10 micromolar (µM) as a cutoff. We first calculated a z-score for quantifying the significance of the shortest path lengths d(s,t) between targets (t) of a drug (T) and proteins (s) associated with the CV module (S) where the closest distance between a drug and a disease d(S,T) is defined as:

| 1 |

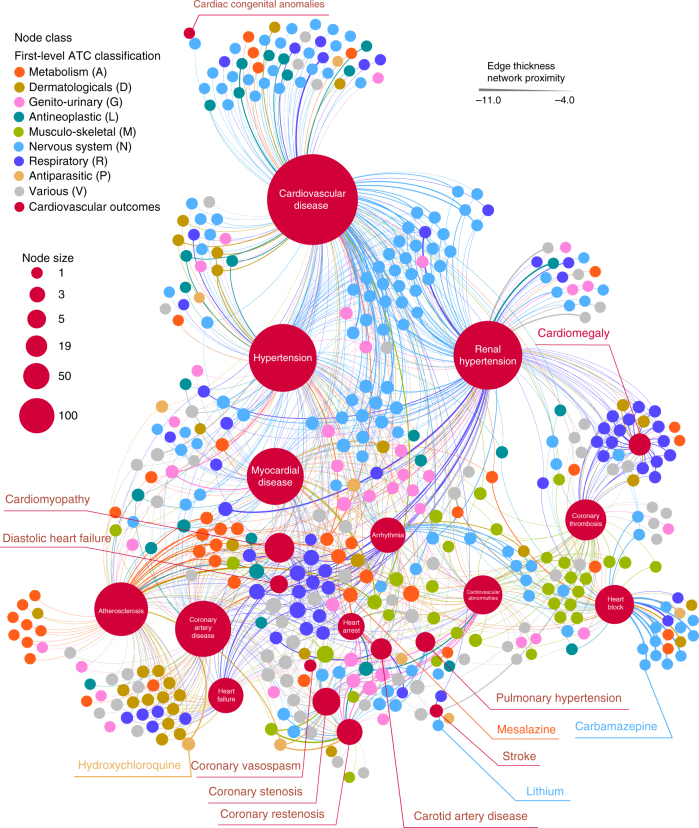

We constructed the reference distance distribution corresponding to the expected network topological distance between two randomly selected groups of proteins matched to size and degree (connectivity) as the original disease proteins and drug targets in the human interactome (cf. Methods). The z-score reduces the study bias (e.g., hub nodes or those nodes with high connectivity) in the shortest-path methods as described in our previous study10. In total, we computationally investigated 984 FDA-approved drugs [177 CV drugs and 807 non-CV drugs defined by first-level Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification codes] and 23 types of CV outcomes (specific CV diseases) (Supplementary Table 1). Relying on 177 FDA-approved CV drugs and their known CV indications, we found that the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) is over 70% using the network proximity measure (Supplementary Fig. 2), revealing high accuracy for identifying the well-known drug-disease relationships. In addition, we compared the network proximity measure, closest (z-score), against three other network distance-based measures between drug targets and the disease module10: (1) shortest, (2) kernel, and (3) centre. We found that the closest distance-based z-score outperformed all three alternative network distance measures (Supplementary Fig. 3). We, therefore, used the closest distance-based z-score in the follow-up studies. Figure 1 illustrates the high-confidence predicted drug-CV disease associations (z < −4.0) connecting 431 non-CV drugs to 22 specific CV disease modules. We next proposed that this atlas of the predicted associations between non-CV drugs and CV disorders offers a useful resource with which to prioritize new CV indications or highlight potential (unexpected) adverse cardiac events for various approved drugs.

Fig. 1.

The predicted drug-disease network. The high-confidence predicted drug-disease association network connects 22 types of cardiovascular disease (outcomes) (red circles) and 431 FDA-approved non-cardiac drugs. The edges between drugs and diseases are weighted and highlighted by different color representing the calculated z-score (Supplementary Data 2 and Methods section). Four selected drug-disease pairs, including carbamazepine-coronary artery disease (CAD) with z = −2.36, hydroxychloroquine-CAD (z = −3.85), mesalamine-CAD (z = −6.10), and lithium-stroke (z = −5.97), tested in patient data (Figs. 2 and 3), are highlighted. Drugs are colored by the first-level anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) classification system codes. The node size scales indicate the degree (connectivity) of nodes in the network

Validating possible causal associations in patient data

We selected four target associations between non-CV drugs and CV diseases identified by the network proximity measure (closest) for hypothesis validation by analyzing over 220 million patients in healthcare databases (Fig. 2). Target associations were further selected using subject matter expertise based on a combination of factors: (i) strength of the network-based predicted associations (a higher network proximity score in Supplementary Data 2); (ii) novelty of the predicted associations through exclusion of known adverse CV events of non-CV drugs (Methods section); (iii) availability of sufficient patient data for meaningful evaluation (exclusion of infrequently used medications); (iv) availability of an appropriate comparator treatment that is used for the same underlying (non-CV) indication as the drug of interest and predicted to have no association with the intended CV diseases via network proximity analysis (defined reference groups or negative controls); and (v) the fidelity with which the predicted CV diseases were recorded in insurance claims databases. Applying these criteria resulted in four network-based predictions: (1) carbamazepine (z = −2.36) vs. levetiracetam (comparator control, z = −0.07), drugs normally used to treat epilepsy, with CAD; (2) mesalamine (z = −6.10) vs. azathioprine (comparator control, z = −0.09), drugs normally used to treat inflammatory bowel disease, with CAD; (3) hydroxychloroquine (z = −3.85) vs. leflunomide (comparator control, z = −1.87), drugs normally used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, with CAD; and (4) lithium (z = −5.97) vs. lamotrigine (comparator control, z = 0.19), drugs normally used to treat bipolar disorder, with stroke.

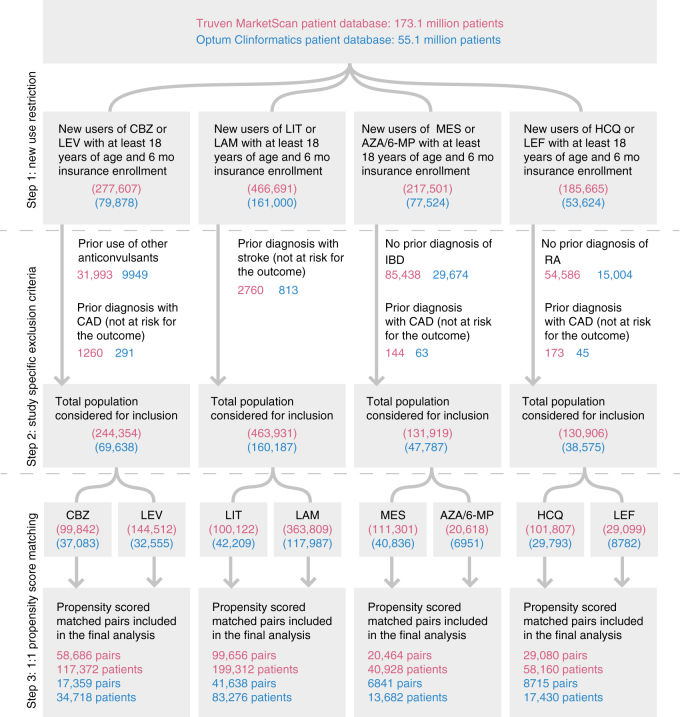

Fig. 2.

Flow-chart of the pharmacoepidemiologic investigations using Truven MarketScan and Optum Clinformatics patient databases. AZA azathioprine, 6-MP 6-mercaptopurine, CBZ carbamazepine, HCQ hydroxychloroquine, IBD inflammatory bowel disease, LAM lamotrigine, LEF leflunomide, LEV levetiracetam, LIT lithium, MES mesalamine, RA rheumatoid arthritis. The balance achieved in patient characteristics and outcome risk factors between the two treatment groups compared through 1:1 PS-matching are provided in Supplementary Tables 2–5

Using two large US-based commercial health insurance claims databases connected with the validated Aetion evidence platform20, we next conducted four cohort studies to evaluate the predicted associations based on individual level longitudinal patient data and pharmacoepidemiologic methods, including a new-user active comparator design, propensity score (PS) adjustment for confounding, and multiple sensitivity analyses21. Figure 2 summarizes the total patients included in the four cohorts along with specific reasons for exclusion in the Truven MarketScan and Optum Clinformatics databases. Overall, based on more than 50 covariates included in the PS, we included: (1) 76,045 carbamazepine initiators matched 1:1 to 76,045 levetiracetam initiators; (2) 27,305 mesalamine initiators matched 1:1 to 27,305 azathioprine initiators; (3) 37,795 hydroxychloroquine initiators matched 1:1 to 37,795 leflunomide initiators; and (4) 141,294 lithium initiators matched 1:1 to 141,294 lamotrigine initiators. Supplementary Tables S2–S5 demonstrate the balance achieved in patient characteristics and outcome risk factors between the two treatment groups compared via 1:1 PS-matching. Table 1 shows the total number of person-years of follow-up, total event counts (incident diseases) in the patient groups, and incidence rates per 1000 person-years for the diseases of interest (95% confidence interval [CI]) for each of the four comparisons of interest stratified by data source.

Table 1.

Summary of sample sizes, follow-up time, events, and incidence rates in pharmacoepidemiologic investigations

| Parameter | Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | Study 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New users of carbamazepine | New users of levetiracetam | New users of lithium | New users of lamotrigine | New users of mesalamine | New users of azathioprine/6-MP | New users of hydroxychloroquine | New users of leflunomide | |

| Database 1: Truven MarketScan | ||||||||

| Patients | 58,686 | 58,686 | 99,656 | 99,656 | 20,464 | 20,464 | 29,080 | 29,080 |

| Person-years | 27,050 | 31,826 | 46,278 | 61,970 | 8714 | 11,562 | 18,650 | 17,293 |

| Outcomesa | 124 | 105 | 67 | 90 | 17 | 27 | 88 | 106 |

| Incidence rate per 100 person-years (95% CI) | 0.46 (0.38, 0.55) |

0.33 (0.27, 0.40) |

0.14 (0.11, 0.18) | 0.15 (0.12, 0.18) | 0.20 (0.11, 0.31) | 0.23 (0.15, 0.34) |

0.47 (0.38, 0.58) |

0.61 (0.50, 0.74) |

| Database 2: Optum Clinformatics | ||||||||

| Patients | 17,359 | 17,359 | 41,638 | 41,638 | 6841 | 6841 | 8715 | 8715 |

| Person-years | 8662 | 8945 | 18,925 | 24,627 | 2589 | 3587 | 5376 | 5043 |

| Outcomesa | 56 | 30 | 10 | 31 | 15 | 11 | 29 | 39 |

| Incidence rate per 100 person-years (95% CI) | 0.65 (0.49, 0.84) |

0.34 (0.23, 0.48) |

0.05 (0.03, 0.10) | 0.13 (0.09, 0.18) | 0.58 (0.32, 0.96) | 0.31 (0.15, 0.55) |

0.54 (0.36, 0.77) |

0.77 (0.55, 1.06) |

aThe outcome is coronary artery disease for Studies 1, 3, and 4; and stroke for Study 2.

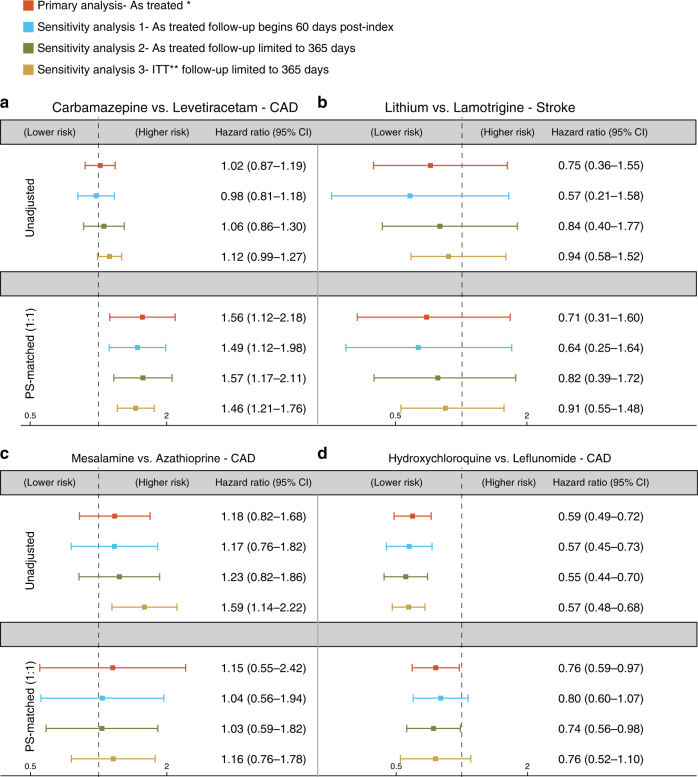

Figure 3 summarizes the results after pooling the two patient databases for each of the four comparisons before and after PS-matching. In the primary analytical approach of censoring patient follow-up time at discontinuation of the initial treatment (“as-treated” approach), we observed that carbamazepine was associated with a 56% increased risk [hazard ratio (HR) 1.56, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.12–2.18] of CAD compared with levetiracetam (Fig. 3a), and hydroxychloroquine (Fig. 3d) was associated with a 24% reduced risk of CAD compared to leflunomide (HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.59–0.97). Varying the follow-up assumptions used in the following ways—(1) excluding the first 60 days of follow-up to reduce residual baseline confounding, (2) truncating the follow-up to 1-year to minimize time-varying confounding, and (3) continuing the follow-up for 1-year regardless of treatment discontinuation under an intent-to-treat (ITT) principle–resulted in estimates that were consistent with the primary approach for both the carbamazepine (Fig. 3a) and hydroxychloroquine analyses (Fig. 3d). Mesalamine vs. azathioprine (HR 1.15, 95% CI 0.55–2.42) and lithium vs. lamotrigine (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.31–1.60) were not consistently associated differentially with the risk of CAD or stroke (Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). Therefore, two of the four predicted associations were validated by the large-scale patient data to either decrease the risk of CAD (hydroxychloroquine) or increase the risk of CAD (carbamazepine), supporting our network-based prediction.

Fig. 3.

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for four cohort studies. Four cohort studies were performed using the pooled data from four drug pairs (a-d) Truven MarketScan and Optum Clinformatics databases (Methods section). In the primary analysis approach (as-treated), follow-up was stopped upon discontinuation of the index medication. Follow-up assumptions were varied in three sensitivity analyses to: (1) exclude the first 60 days of follow-up to reduce unmeasured baseline confounding, (2) truncate the follow-up to 1-year to minimize time-varying confounding, and (3) continue the follow-up for 1-year regardless of treatment discontinuation under an intent-to-treat (ITT) principle. Propensity score (PS) matching accounted for >50 relevant patient characteristics; all analyses were conducted separately in two databases and results were pooled using the DerSimonian and Laird random effects model with inverse variance weights. * In the as-treated approach, the follow-up was stopped if patients either filled a prescription for a drug in the other exposure group or discontinued the index exposure. ** In the ITT analysis, patients were followed in their index exposure group regardless of treatment change or discontinuation for up to 365 days

In vitro assay of hydroxychloroquine’s mechanism-of-action

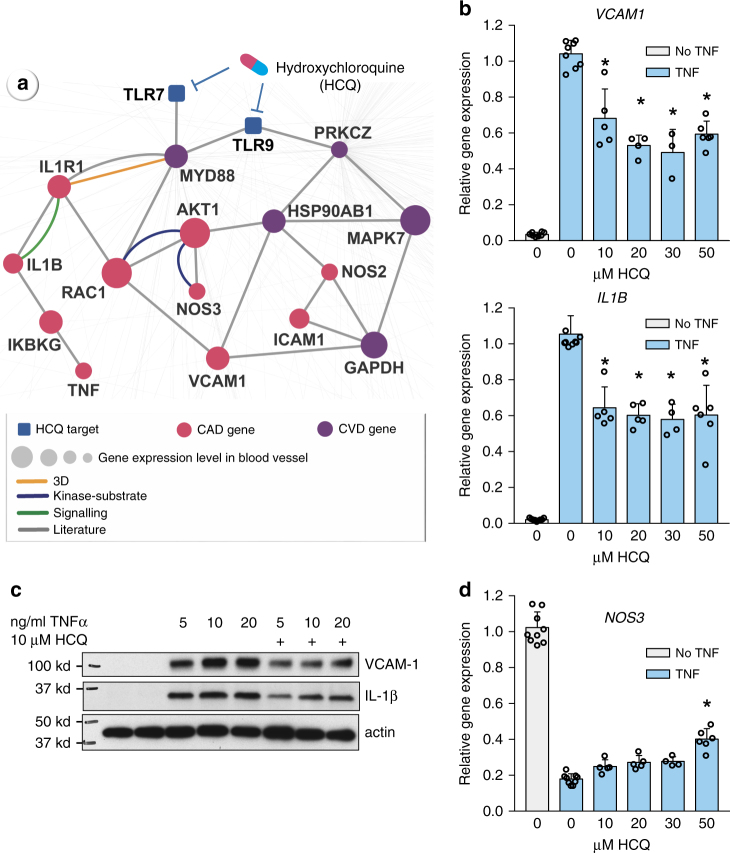

Figure 3d reveals that hydroxychloroquine is associated with a 24% reduced risk of CAD compared to leflunomide (HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.59–0.97). [These very robust data are in agreement with a recent study showing that hydroxychloroquine decreases the incidence of CV events in a small cohort of rheumatoid arthritis patients22.] Hydroxychloroquine has been approved for the treatment of malaria and rheumatoid arthritis for many years; however, only recently have studies provided relevant mechanistic insights. Hydroxychloroquine accumulates intracellularly in the endosomal/lysosomal compartment where its inhibitory effects on Toll-like receptors 7 and 9 (TLR7 and TLR9) suppress inflammatory responses23. We integrated drug targets and disease proteins into the blood vessel-specific protein–protein interaction network (cf. Methods) to identify the overlapping pathways between hydroxychloroquine targets and CAD proteins (Fig. 4a). Two potential pathways were inferred to be involved in the protective effect of hydroxychloroquine in CAD: (a) hydroxychloroquine may activate ERK5 (encoded by MAPK7) to prevent endothelial inflammation via inhibition of cell adhesion molecule expression24; and (b) hydroxychloroquine may inhibit endosomal activation of NADPH oxidase in response to pro-inflammatory agonists (TNF-α and IL-1β) and may decrease production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in stimulated immune cells25. Notably, adhesion molecules (ICAM-1 and VCAM-1)26 and pro-inflammatory cytokines27 play essential roles in CAD. Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis has shown that elevated expression of TNF-α or IL-1β is significantly associated with increased risk of CAD28. Thus, we sought to determine whether hydroxychloroquine has direct anti-inflammatory effects on endothelial cells via these pathways as a potential beneficial mechanism in CAD.

Fig. 4.

Experimental validation of hydroxychloroquine’s likely mechanism-of-action in coronary artery disease (CAD). a A highlighted subnetwork shows the inferred mechanism-of-action for hydroxychloroquine’s protective effect in CAD by network analysis. A network analysis was designed to meet four criteria: (1) the shortest paths from the known drug targets (TLR7 and TLR9) in the human protein–protein interaction network; (2) the blood vessel-specific gene expression level based on RNA-seq data from Genotype-Tissue Expression database; (3) known CAD or cardiovascular disease (CVD) gene products (proteins); and (4) literature-reported in vitro and in vivo evidence. There are three proposed mechanisms: (i) ERK5 (encoded by MAPK7) activation prevents endothelial inflammation via inhibition of cell adhesion molecule expression (VCAM-1 and ICAM-1), (ii) suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β), and (iii) improvement in endothelial dysfunction via enhanced nitric oxide production by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS3). The node size scales show the blood vessel-specific expression level based on RNA-seq data from Genotype-Tissue Expression database (Methods section). b, d Endothelial cells were pretreated with various concentrations of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ, 10–50 µM) for 1 h prior to 24 h incubation with 5 ng/ml TNF-α. qRT-PCR was used to monitor gene expression of inflammatory genes (b) VCAM1 and IL1B; and (d) NOS3. Expression of the β-actin gene was used as an internal standard. VCAM1: no HCQ, no TNF, n = 8; TNF; n = 8; TNF+ 10 μM HCQ, n = 5; TNF+ 20 μM HCQ, n = 4; TNF+ 30 μM HCQ, n = 3; TNF+ 50 μM HCQ, n = 6. IL-1β and NOS3: no HCQ, no TNF, n = 9; TNF; n = 9; TNF+ 10 μM HCQ, n = 5; TNF+ 20 μM HCQ, n = 5; TNF+ 30 μM HCQ, n = 4; TNF+ 50 μM HCQ, n = 6. Error bars are standard deviations. *significantly different from TNF-α with no HCQ, p < 0.05 as determined by post-hoc testing using the Student's Newman–Keuls test. c Western blot of VCAM-1, IL-1β, and actin. Endothelial cells were pretreated with 10 µM hydroxychloroquine for 1 h prior to 24 h incubation with 5, 10 or 20 ng/ml TNF-α. Each condition was tested six times; shown are representative blots

We pretreated human aortic endothelial cells with 10–50 µM hydroxychloroquine and monitored the expression of VCAM1 and IL1B genes in the presence and absence of the cytokine TNF-α. TNF-α (5 ng/ml) caused a robust increase in the expression of VCAM1 and IL1B, and this pro-inflammatory effect was significantly attenuated by all of the doses of hydroxychloroquine tested (Fig. 4b). Similarly, hydroxychloroquine decreased inflammatory responses to 10 and 20 ng/ml TNF-α, as demonstrated by its attenuation of TNF-α-mediated VCAM-1 and IL-1β protein upregulation (Fig. 4c).

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis are reported to have increased endothelial dysfunction29 that correlates with cardiovascular disease risk30. Therefore, we next tested whether hydroxychloroquine altered TNF-α-induced suppression of NOS3 expression31, a known marker of endothelial (dys) function. NOS3 encodes the endothelial nitric oxide synthase enzyme, which, via its synthesis of nitric oxide, regulates vascular tone, impairs platelet activation, and impairs adhesion molecule expression contributing to an anti-inflammatory (and anti-atherogenic) phenotype. TNF-α significantly suppressed NOS3 expression, and 50 µM hydroxychloroquine significantly attenuated (reversed) this suppression (Fig. 4d). Taken together, network proximity analysis of the human interactome not only identified a novel protective effect of hydroxychloroquine in CAD, but also offered testable hypotheses by which to elucidate the molecular mechanism(s) of its protective effect.

Although there may be additional pathways for the beneficial actions of hydroxychloroquine that are outside of the blood-vessel-specific protein–protein interaction network, these experimental findings suggest that hydroxychloroquine has a protective, anti-inflammatory effect on endothelial cells, consistent with its potential beneficial effect in CAD.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that an integrated, mechanism-based human protein–protein interactome strategy can successfully uncover novel drug-disease indications, undesirable side effects, and potential mechanisms for these actions of approved drugs, addressing a crucial issue in drug development and patient care. We showed that our network framework yielded over 70% accuracy for identification of well-known drug indications (Supplementary Fig. 2). Specifically, our network-prediction and pharmacoepidemiological analysis reveal that carbamazepine is associated with an increased risk of CAD compared with levetiracetam, which we are able to validate robustly in large-scale patient data (HR 1.56, 95% CI 1.12–2.18, Fig. 3a). Carbamazepine is a first-line widely used anticonvulsant for the treatment of epilepsy and pain associated with trigeminal neuralgia, and works via inhibition of sodium channel protein type 5 subunit alpha (SCN5A)32 and ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels33. Previous clinical studies have suggested that carbamazepine aggravates high-grade heart block34 and is associated with various cardiovascular risk factors35, consistent with our observations. Moreover, recent genetic studies have shown that mutations in SCN5A and KATP channel genes are associated with structural heart disease36 and adverse cardiac events37,38. Thus, it is mechanistically feasible that inhibition of SCN5A and KATP channel activities by carbamazepine may be associated with the increased risk of CV diseases. Further studies will be needed to provide experimental and clinical validation of this conclusion.

Pharmacoepidemiologic analyses from the two patient databases revealed an inconsistent association of lithium vs. lamotrigine on the risk of stroke: a null result (HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.79–1.33, Supplementary Fig. 4) in the Truven MarketScan database and a 52% reduced risk of stroke (HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.25–0.93, Supplementary Fig. 5) in the Optum Clinformatics database. Recent studies have shown the potentially protective effect of lithium in stroke39. Thus, to explore the effect of lithium in stroke further, we examined the potential molecular mechanism of lithium in the CV system via network analysis and in vitro assays of lithium exposure in cultured human aortic endothelial cells (Supplementary Fig. 6). We found a subnetwork of stroke genes and genes up- or down-regulated by lithium (Supplementary Fig. 6a) that map to pathways involved in the production of nitric oxide, which not only has anti-thrombotic effects but also vascular and neural protective effects in the central nervous system; however, our subsequent analysis in human aortic endothelial cells suggested that lithium may attenuate activation of these protective pathways (Supplementary Figs. 6b–e). In vitro assay results are consistent with a recent study that maternal use of high-dose lithium during the first trimester is associated with an increased risk of cardiac malformation in the foetus40. Thus, our findings suggest that larger clinical trials and additional mechanistic studies may be necessary to clarify lithium’s action in stroke prevention in a broad population or a well-defined sub-population.

Although patients with rheumatoid arthritis on hydroxychloroquine had a lower risk of CAD than rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with leflunomide, the ability of hydroxychloroquine to improve outcomes in patients with other underlying risk factors for CAD is unclear. Nonetheless, several CVD and CAD proteins are found within the hydroxychloroquine subnetwork (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, hydroxychloroquine has anti-inflammatory properties41,42, and inflammation is a known major contributor to CAD43. In a mouse model of atherosclerosis, hydroxychloroquine was found to have anti-atherogenic and vasculoprotective effects44, suggesting its utility in preventing vascular remodeling. Herein, our in vitro assays reveal that hydroxychloroquine attenuates the pro-inflammatory cytokine-mediated activation of human aortic endothelial cells (Fig. 4b–d) by reducing the expression of adhesion molecules, decreasing the production of cytokines, and attenuating the suppression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Although additional mechanistic studies are necessary to confirm the beneficial effects of hydroxychloroquine on endothelial function in the context of CAD, the anti-inflammatory properties of hydroxychloroquine on other cell types is well known. In rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus, hydroxychloroquine has been suggested to mediate its anti-inflammatory action by inhibiting the activation of TLR7 and TLR9 that reside in endosomal/lysosomal compartments23. Recent evidence suggests that internalization of TNF-α receptors and other plasma membrane receptors to endosomal compartments may be a necessary step in the activation of certain ligand-induced signaling pathways45. Thus, hydroxychloroquine, which accumulates in endosomes, may interfere with the inflammatory actions of multiple types of membrane receptors.

In support of an effect of hydroxychloroquine on endosomal signaling, assembly of NADPH oxidase 2 complexes in the endosome in response to pro-inflammatory stimuli was attenuated by hydroxychloroquine to reduce superoxide generation in monocytes46. Additionally, in a monocytic cell line, hydroxychloroquine attenuated TNF-α and IL6 expression in response to IL-1β and TNF-α stimulation, respectively46. Interestingly, a treatment trial (the OXI trial) has recently been initiated to assess the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in preventing recurrent CV events in patients with myocardial infarction47 owing to its anti-inflammatory effects as well as its additional biological actions48. The results of this ongoing trial may provide further insights into the cardioprotective actions of hydroxychloroquine in a subset of non-rheumatoid arthritis patients.

Our pharmacoepidemiologic method, relying on very large patient-level longitudinal data, has several advantages. First, we used two large population-based cohorts to validate the hypothesized associations, which allowed for statistically robust testing of small effect sizes in relatively small treatment subpopulations. Pharmacy dispensing data from insurance claims were used to define exposure to medications. This approach is generally considered to be more accurate than self-reported drug use or medical records49. We also applied a large number of covariates to account for confounding in our studies using the recommended approach of PS-matching for improving inference from large healthcare databases, which are increasingly recognized by regulators and payers as a vital source of information through which to understand the safety and effectiveness of medications used in routine care50. We conducted multiple sensitivity analyses to rule out chance findings and attempted to replicate our analyses in a second large database. However, there remain certain limitations of this approach. Insurance claims data are primarily collected for administrative purposes and do not contain detailed clinical information; therefore, residual confounding is possible despite high-dimensional covariate adjustment. We defined outcomes purely by using a claims-based definition; although, we used validated and specific codes, endpoints could not be adjudicated. Finally, our databases did not contain information on patient ethnicity, which is also a limitation. Replication of the associations identified in this study using databases that contain information on ethnicity is recommended in future studies to rule out treatment effect heterogeneity by ethnicity.

In summary, we demonstrated that an integration of molecular network-based approaches and state-of-the-art pharmacoepidemiologic methods can facilitate rational strategies for drug repurposing and the detection of side effects. Specifically, we observed that hydroxychloroquine was associated with 24% reduced risk of CAD compared with leflunomide using large-scale patient data, effects that are supported by mechanistic in vitro data. In addition, carbamazepine was associated with a 56% increased risk of CAD compared with levetiracetam. We believe that the approach presented here, if broadly applied, would significantly catalyze innovation in drug discovery and development.

Methods

Building the human protein–protein interactome

To build the comprehensive human protein–protein interactome as currently available, we assembled 15 commonly used databases with multiple types of experimental evidence and the in-house systematic human protein–protein interactome: (1) binary PPIs tested by high-throughput yeast-two-hybrid (Y2H) systems in which we combined binary PPIs tested from two publicly available high-quality Y2H datasets19,51 and one dataset available from our website: http://ccsb.dana-farber.org/interactome-data.html; (2) kinase-substrate interactions from literature-derived low-throughput and high-throughput experiments from KinomeNetworkX52, Human Protein Resource Database (HPRD)53, PhosphoNetworks54,55, PhosphositePlus56, dbPTM 3.057, and Phospho.ELM58; (3) carefully literature-curated PPIs identified by affinity purification followed by mass spectrometry (AP-MS), and from literature-derived low-throughput experiments from BioGRID59, PINA60, HPRD53, MINT61, IntAct62, and InnateDB63; (4) high-quality PPIs from three-dimensional (3D) protein structures reported in Instruct64; and (5) signaling networks from literature-derived low-throughput experiments as annotated in SignaLink2.065. The genes were mapped to their Entrez ID based on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database66 as well as their official gene symbols based on GeneCards (http://www.genecards.org/). Inferred data, such as evolutionary analysis, gene expression data, and metabolic associations, were excluded. The updated human interactome constructed in this way includes 243,603 protein–protein interactions (PPIs) (edges or links) connecting 16,677 unique proteins (nodes) (Supplementary Data 1), representing over 40% greater size compared to our previously utilized human interactome6.

Collection of human cardiovascular disease genes

We began with ~50 types of CV events defined by Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) vocabularies67. For each CV event, we collected disease-associated genes from 8 commonly used data sources: The OMIM database (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man)68, The Comparative Toxicogenomics Database69, HuGE Navigator70, DisGeNET71, ClinVar72, GWAS Catalog73, GWASdb74, and PheWAS Catalog (phewas.mc.vanderbilt.edu)75. We annotated all protein-coding genes using gene Entrez ID, chromosomal location, and the official gene symbols from the NCBI database66. Here we selected CV events with at least 10 disease-associated genes in the human interactome, resulting in 23 types of CV events (Supplementary Table 1).

Construction of drug-target network

We assembled the physical drug-target interactions on FDA-approved drugs from 6 commonly used data sources, and defined a physical drug-target interaction using reported binding affinity data: inhibition constant/potency (Ki), dissociation constant (Kd), median effective concentration (EC50), or median inhibitory concentration (IC50) ≤10 µM. Drug-target interactions were acquired from the DrugBank database (v4.3)76, the Therapeutic Target Database (TTD, v4.3.02)77, and the PharmGKB database (30 December 2015)78. Specifically, bioactivity data of drug-target pairs were collected from three commonly used databases: ChEMBL (v20)79, BindingDB (downloaded in December 2015)80, and IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (downloaded in December 2015)81. After extracting the bioactivity data related to the drugs from the prepared bioactivity databases, only those items meeting the following four criteria were retained: (i) binding affinities, including Ki, Kd, IC50, or EC50 ≤10 μM; (ii) proteins can be represented by unique UniProt accession number; (iii) proteins are marked as reviewed in the UniProt database82; and (iv) proteins are from Homo sapiens.

Description of network proximity

Given S, the set of disease proteins, T, the set of drug targets, and d(S,T), the closest distance measured by the average shortest path length between nodes s and the nearest disease protein t in the human protein–protein interactome is defined as: . To evaluate the significance of the network distance between a drug and a given disease, we constructed a reference distance distribution corresponding to the expected distance between two randomly selected groups of proteins of the same size and degree distribution as the original disease proteins and drug targets in the network. This procedure was repeated 1000 times. The mean and s.d. (σd) of the reference distribution were used to calculate a z-score (zd) by converting an observed (non-Euclidean) distance to a normalized distance.

Pharmacoepidemiologic methodology

We conducted observational cohort studies using two large US-based health insurance claims databases: (1) Truven MarketScan (2003–2014), and (2) Optum Clinformatics (2004–2013). These data sources contain comprehensive longitudinal information on patient demographics, coded in-patient and out-patient diagnoses and procedures, and outpatient prescription dispensing for their enrollees. Use of the de-identified database was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

We identified patients 18 years or older who initiated treatment with the drug of interest after 180 days of continuous enrollment83. The date on which this new prescription was filled was defined as the index date. We further applied study-specific exclusion criteria (summarized in Fig. 2) in the 180-day pre-index period to include homogeneous groups of patients in each comparison and focused on incident events. The follow-up began on the day after the index date. For the primary analysis, we used an as-treated follow-up approach in which the follow-up was stopped if patients either filled a prescription for a drug in the other exposure group or discontinued the index exposure. Discontinuation was defined as no record of a subsequent prescription of the index medication for 60 days after accounting for the days’ supply of exposure provided by the most recent prescription. We varied the follow-up approach to evaluate the robustness of our results in three sensitivity analyses. First, we did not attribute the outcome occurring in the first 60-days post-index to the index treatment to avoid the possibility of unmeasured baseline confounding. Second, we truncated the follow-up to a maximum of 365-days to limit the potential for time-varying confounding. Finally, we conducted an intention-to-treat (ITT) equivalent analysis in which patients were followed in their index exposure group regardless of treatment change or discontinuation for up to 365 days. In all of the approaches, the follow-up was truncated at the first outcome occurrence, health insurance disenrollment, death, or the most recent date of data availability.

The outcome of CAD was identified as a composite endpoint of hospitalization for myocardial infarction as the primary discharge diagnosis or a coronary revascularization procedure. The ICD-9 codes and CPT codes used to identify these outcomes have been found to have >90% positive predictive value (PPV) in administrative claims databases84,85. The outcome of stroke was identified using hospitalization claims where ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack was recorded as the primary discharge diagnosis. The ICD-9 codes used to identify this outcomes have been found to have 96% positive predictive value (PPV) in administrative claims databases86.

We identified the large number of covariates, which were measured in the 180-day baseline period preceding each patient’s index date, in each of the four studies to account for confounding. These variables were specifically selected to address clinical scenarios evaluated in each study. For example, in the study of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) treatments (mesalamine vs. azathioprine), we measured and accounted for IBD severity-related variables, such as diagnosis for active fistula formation or internal penetrating disease, obstructing or stricturing disease, and intra-abdominal surgical procedures. Additionally, patient demographics (age and gender), risk factors for cardiovascular diseases (e.g., hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, cardiovascular medication use), and markers of contact with the healthcare system (e.g., number of emergency department visits, number of distinct prescription medications used) were measured in all four studies. Please refer to Supplementary Tables 2–5 for a full list of covariates included in each study.

We used propensity score (PS) methods to account for potential confounding87. PSs were defined as the predicted probability of receiving the treatment of interest (vs. the comparator) conditional upon patients’ covariate constellations and were calculated using multivariable logistic regression models, including the covariates described above as independent variables. Initiators of each exposure of interest were matched to initiators of the reference exposure based on their PS in 1:1 ratio using a nearest-neighbor algorithm within a caliper of 0.05 on the probability scale88. Cox-proportional hazards models were used to estimate the adjusted hazard ratios (HR) between the treatment of interest and the risk of outcome before and after PS-matching. All analyses were conducted separately in the two data sources to avoid any potential effect of differential measurement of study variables across the data sources on the comparative estimates. The results were presented after pooling estimates from the two databases using the DerSimonian and Laird random effects model with inverse variance weights89. To address the possibility of population-overlap, we corrected the variance of our pooled hazard ratios assuming 20% overlap between the two databases as follows:

All statistical analyses were conducted on the Aetion Platform version 2.1.2 using R (version 3.1.2), which has been validated against the FDA Sentinel system and randomized control trials20.

Tissue-specific subnetwork analysis

We downloaded the RNA-seq data (RPKM value) of 32 tissues from GTEx V6 release (accessed on 01 April 2016, https://gtexportal.org/home/). For each tissue (e.g., blood vessel), we regarded those genes with RPKM ≥1 in >80% of samples as tissue-expressed genes and the remaining genes as tissue-unexpressed. To quantify the expression significance of tissue-expressed gene i in tissue t, we calculated the average expression 〈E(i)〉 and the standard deviation of a gene’s expression across all considered tissues90. The significance of gene expression in tissue t is defined as . For stroke and CAD, we built a blood vessel-specific protein–protein interaction network by comparing genome-wide expression profiles of blood vessels to 31 other different tissues from GTEx.

In in vitro assays, human aortic endothelial cells (Lonza) were passaged in EGM-2 (Lonza) with the addition of hydroxychloroquine (Fig. 4) or lithium chloride (Supplementary Fig. 6) at the doses and times indicated. To assess VEGF-mediated activation of Akt/GSK/eNOS signaling, cells were cultured 24 h in EBM-2 with 0.1% fetal bovine serum in the presence of absence of lithium chloride prior to the addition of VEGF at 50 ng/ml for the times indicated (Supplementary Fig. 6). One hour after cells were exposed to hydroxychloroquine (10–50 μM), TNF-α (5–20 ng/ml) was added to the media. Cells were collected 24 h following TNF-α addition for RNA or protein analysis (Fig. 4).

RNA was collected from cells with the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) using the optional DNase I digestion. cDNA was synthesized from 0.5 μg of RNA using oligo dT primers and the Advantage RT-for-PCR kit (Clontech). Relative RNA levels were measured by quantitative RT-PCR method using the ΔΔCt method of analysis. β-Actin was used as the endogenous control. The following TaqMan probes (Thermo Fisher) were used for gene expression analysis: VCAM1, Hs00365485_m1; IL1B, Hs01555410_m1; NOS3, Hs01574659_m1 and ACTB, Hs99999903_m1.

Radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer was supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Calbiochem) and used to collect cell extracts. Cell lysates were separated on 4–15% polyacrylamide gradient gels (Biorad), and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling. VCAM-1 was detected by western blotting using an sc-8304 antibody (Santa Cruz) at a 1:4000 dilution; IL-1β actin was detected using a 1:1000 dilution of antibody #12703 (Cell Signaling); and actin was detected using a 1:4000 dilution of antibody #4970 (Cell Signaling). A secondary anti-rabbit-HRP antibody (Cell Signaling, #7074) was used at 1:2000 together with the ECL western blotting detection reagents from GE Healthcare. Blots were exposed to X-ray film, and the Biorad ChemiDoc Touch Imaging system was used to generate images. For western blot experiments designed to analyze the effects of hydroxychloroquine, each condition was tested in 6 independent experiments. Uncropped scans of the blots used in Fig. 4c are included in Supplementary Fig. 7.

Code availability

The toolbox package for the network proximity calculation can be downloaded at github.com/emreg00/toolbox.

Data availability

The human publicly available protein–protein interactome used in this study is freely available as a supplement to this manuscript (Supplementary Data 1). The unpublished binary human protein–protein interactions can be accessed at http://ccsb.dana-farber.org/interactome-data.html. The global predicted z-scores for 984 FDA-approved drugs and 23 types of cardiovascular events (diseases) via the network proximity approach are freely available in Supplementary Data 2. All other relevant data are available from the authors.

Electronic supplementary material

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH grants P50-HG004233, U01-HG001715, and U01-HG007690 from NHGRI, P50-GM107618 from NIGMS and PO1-HL083069, R37-HL061795, RC2-HL101543, U01-HL108630, RC4-HL106373, and K99HL138272 from NHLBI, and ME-1303–5638 from PCORI.

Author contributions

J.L., A.-L.B., and S.S. conceived the study. F.C., R.J.D., D.E.H., performed all experiments and analysis. R.W. performed data analysis. F.C., R.J.D., D.E.H., S.S., A.-L.B., and J.L. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

A.-L.B. and J.L. are co-founders of Scipher, a startup that uses network concepts to explore human disease. S.S. is consultant to Aetion, Inc., a software manufacturer in which he also owns equity. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Feixiong Cheng, Rishi J. Desai

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-05116-5.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mullard A. 2016 FDA drug approvals. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017;16:73–76. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shih HP, Zhang X, Aronov AM. Drug discovery effectiveness from the standpoint of therapeutic mechanisms and indications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017;17:19–33. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antman EM, Loscalzo J. Precision medicine in cardiology. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2016;13:591–602. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacRae CA, Roden DM, Loscalzo J. The future of cardiovascular therapeutics. Circulation. 2016;133:2610–2617. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greene JA, Loscalzo J. Putting the patient back together - social medicine, network medicine, and the limits of reductionism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:2493–2499. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1706744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menche J, et al. Disease networks. Uncovering disease-disease relationships through the incomplete interactome. Science. 2015;347:1257601. doi: 10.1126/science.1257601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yildirim MA, Goh KI, Cusick ME, Barabasi AL, Vidal M. Drug-target network. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:1119–1126. doi: 10.1038/nbt1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang RS, Loscalzo J. Illuminating drug action by network integration of disease genes: a case study of myocardial infarction. Mol. Biosyst. 2016;12:1653–1666. doi: 10.1039/C6MB00052E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dudley JT, et al. Computational repositioning of the anticonvulsant topiramate for inflammatory bowel disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:96ra76. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guney E, Menche J, Vidal M, Barabasi AL. Network-based in silico drug efficacy screening. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10331. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao S, et al. Systems pharmacology of adverse event mitigation by drug combinations. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;5:206ra140. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Himmelstein DS, et al. Systematic integration of biomedical knowledge prioritizes drugs for repurposing. eLife. 2017;6:e26726. doi: 10.7554/eLife.26726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneeweiss S, et al. Real world data in adaptive biomedical innovation: a framework for generating evidence fit for decision making. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016;100:633–646. doi: 10.1002/cpt.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneeweiss S, Avorn J. A review of uses of health care utilization databases for epidemiologic research on therapeutics. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2005;58:323–337. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneeweiss S, et al. High-dimensional propensity score adjustment in studies of treatment effects using health care claims data. Epidemiology. 2009;20:512. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a663cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brilliant MH, et al. Mining retrospective data for virtual prospective drug repurposing: L-DOPA and age-related macular degeneration. Am. J. Med. 2016;129:292–298. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goh KI, et al. The human disease network. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8685–8690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701361104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghiassian SD, Menche J, Barabasi AL. A DIseAse MOdule Detection (DIAMOnD) algorithm derived from a systematic analysis of connectivity patterns of disease proteins in the human interactome. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015;11:e1004120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rolland T, et al. A proteome-scale map of the human interactome network. Cell. 2014;159:1212–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang SV, et al. Transparency and reproducibility of observational cohort studies using large healthcare databases. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016;99:325–332. doi: 10.1002/cpt.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneeweiss S. A basic study design for expedited safety signal evaluation based on electronic healthcare data. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug. Saf. 2010;19:858–868. doi: 10.1002/pds.1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma TS, et al. Hydroxychloroquine use is associated with decreased incident cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis patients. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002867. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamphier M, et al. Novel small molecule inhibitors of TLR7 and TLR9: mechanism of action and efficacy in vivo. Mol. Pharmacol. 2014;85:429–440. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.089821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le NT, et al. Identification of activators of ERK5 transcriptional activity by high-throughput screening and the role of endothelial ERK5 in vasoprotective effects induced by statins and antimalarial agents. J. Immunol. 2014;193:3803–3815. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muller-Calleja N, Manukyan D, Canisius A, Strand D, Lackner KJ. Hydroxychloroquine inhibits proinflammatory signalling pathways by targeting endosomal NADPH oxidase. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017;76:891–897. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang SJ, et al. Circulating adhesion molecules VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin in carotid atherosclerosis and incident coronary heart disease cases: the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study. Circulation. 1997;96:4219–4225. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.96.12.4219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tousoulis D, Oikonomou E, Economou EK, Crea F, Kaski JC. Inflammatory cytokines in atherosclerosis: current therapeutic approaches. Eur. Heart J. 2016;37:1723–1732. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaptoge S, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and risk of coronary heart disease: new prospective study and updated meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2014;35:578–589. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herbrig K, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis is associated with a reduced number and impaired function of endothelial progenitor cells. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2006;65:157–163. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.035378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandoo A, Kitas GD, Carroll D, Veldhuijzen van Zanten JJ. The role of inflammation and cardiovascular disease risk on microvascular and macrovascular endothelial function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2012;14:R117. doi: 10.1186/ar3847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson HD, Rahmutula D, Gardner DG. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibits endothelial nitric-oxide synthase gene promoter activity in bovine aortic endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:963–969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jaramillo NM, et al. Pharmacogenetic potential biomarkers for carbamazepine adverse drug reactions and clinical response. Drug Metabol. Drug Interact. 2014;29:67–79. doi: 10.1515/dmdi-2013-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen PC, et al. Carbamazepine as a novel small molecule corrector of trafficking-impaired ATP-sensitive potassium channels identified in congenital hyperinsulinism. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:20942–20954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.470948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beermann B, Edhag O, Vallin H. Advanced heart-block aggravated by carbamazepine. Br. Heart J. 1975;37:668–671. doi: 10.1136/hrt.37.6.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Svalheim S, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in epilepsy patients taking levetiracetam, carbamazepine or lamotrigine. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2010;122:30–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2010.01372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saffitz JE. Structural heart disease, SCN5A gene mutations, and Brugada syndrome: a complex menage a trois. Circulation. 2005;112:3672–3674. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.587147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamagata K, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation of SCN5A mutation for the clinical and electrocardiographic characteristics of probands with Brugada syndrome: a Japanese multicenter registry. Circulation. 2017;135:2255–2270. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nichols CG, Singh GK, Grange DK. KATP channels and cardiovascular disease: suddenly a syndrome. Circ. Res. 2013;112:1059–1072. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.300514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lan CC, et al. A reduced risk of stroke with lithium exposure in bipolar disorder: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17:705–714. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patorno E, et al. Lithium use in pregnancy and the risk of cardiac malformations. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;376:2245–2254. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rainsford KD, Parke AL, Clifford-Rashotte M, Kean WF. Therapy and pharmacological properties of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and related diseases. Inflammopharmacology. 2015;23:231–269. doi: 10.1007/s10787-015-0239-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuznik A, et al. Mechanism of endosomal TLR inhibition by antimalarial drugs and imidazoquinolines. J. Immunol. 2011;186:4794–4804. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:1685–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shukla AM, et al. Impact of hydroxychloroquine on atherosclerosis and vascular stiffness in the presence of chronic kidney disease. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0139226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cendrowski J, Maminska A, Miaczynska M. Endocytic regulation of cytokine receptor signaling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2016;32:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muller-Calleja N, Manukyan D, Canisius A, Strand D, Lackner KJ. Hydroxychloroquine inhibits proinflammatory signalling pathways by targeting endosomal NADPH oxidase. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2016;76:891–897. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hartman O, Kovanen PT, Lehtonen J, Eklund KK, Sinisalo J. Hydroxychloroquine for the prevention of recurrent cardiovascular events in myocardial infarction patients: rationale and design of the OXI trial. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2017;3:92–97. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvw035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olsen NJ, Schleich MA, Karp DR. Multifaceted effects of hydroxychloroquine in human disease. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;43:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.West SL, et al. Completeness of prescription recording in outpatient medical records from a health maintenance organization. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1994;47:165–171. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sherman RE, et al. Real-world evidence - what is it and what can it tell us? N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:2293–2297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1609216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rual JF, et al. Towards a proteome-scale map of the human protein-protein interaction network. Nature. 2005;437:1173–1178. doi: 10.1038/nature04209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng F, Jia P, Wang Q, Zhao Z. Quantitative network mapping of the human kinome interactome reveals new clues for rational kinase inhibitor discovery and individualized cancer therapy. Oncotarget. 2014;5:3697–3710. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peri S, et al. Human protein reference database as a discovery resource for proteomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D497–D501. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Newman RH, et al. Construction of human activity-based phosphorylation networks. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2013;9:655. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hu J, et al. PhosphoNetworks: a database for human phosphorylation networks. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:141–142. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hornbeck PV, et al. PhosphoSitePlus, 2014: mutations, PTMs and recalibrations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D512–D520. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu CT, et al. DbPTM 3.0: an informative resource for investigating substrate site specificity and functional association of protein post-translational modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D295–D305. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dinkel H, et al. Phospho.ELM: a database of phosphorylation sites–update 2011. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D261–D267. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chatr-Aryamontri A, et al. The BioGRID interaction database: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D470–D478. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cowley MJ, et al. PINA v2.0: mining interactome modules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D862–D865. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Licata L, et al. MINT, the molecular interaction database: 2012 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D857–D861. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Orchard S, et al. The MIntAct project–IntAct as a common curation platform for 11 molecular interaction databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D358–D363. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Breuer K, et al. InnateDB: systems biology of innate immunity and beyond–recent updates and continuing curation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D1228–D1233. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meyer MJ, Das J, Wang X, Yu H. INstruct: a database of high-quality 3D structurally resolved protein interactome networks. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1577–1579. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fazekas D, et al. SignaLink 2 - a signaling pathway resource with multi-layered regulatory networks. BMC Syst. Biol. 2013;7:7. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coordinators NR. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D7–D19. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bodenreider O. The Unified Medical Language System (UMLS): integrating biomedical terminology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D267–D270. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, Schiettecatte F, Scott AF, Hamosh A. OMIM.org: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM(R)), an online catalog of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D789–D798. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Davis AP, et al. The comparative toxicogenomics database’s 10th year anniversary: update 2015. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D914–D920. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yu W, Gwinn M, Clyne M, Yesupriya A, Khoury MJ. A navigator for human genome epidemiology. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:124–125. doi: 10.1038/ng0208-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pinero J, et al. DisGeNET: a discovery platform for the dynamical exploration of human diseases and their genes. Database. 2015;2015:bav028. doi: 10.1093/database/bav028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Landrum MJ, et al. ClinVar: public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D980–D985. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Welter D, et al. The NHGRI GWAS Catalog, a curated resource of SNP-trait associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D1001–D1006. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li MJ, et al. GWASdb v2: an update database for human genetic variants identified by genome-wide association studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D869–D876. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Denny JC, et al. Systematic comparison of phenome-wide association study of electronic medical record data and genome-wide association study data. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:1102–1110. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Law V, et al. DrugBank 4.0: shedding new light on drug metabolism. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D1091–D1097. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhu F, et al. Therapeutic target database update 2012: a resource for facilitating target-oriented drug discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D1128–D1136. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hernandez-Boussard T, et al. The pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics knowledge base: accentuating the knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D913–D918. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gaulton A, et al. ChEMBL: a large-scale bioactivity database for drug discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D1100–D1107. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu TQ, Lin YM, Wen X, Jorissen RN, Gilson MK. BindingDB: a web-accessible database of experimentally determined protein-ligand binding affinities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D198–D201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pawson AJ, et al. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert-driven knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D1098–D1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Apweiler R, et al. UniProt: the Universal Protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D115–D119. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ray WA. Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: new-user designs. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003;158:915–920. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kiyota Y, et al. Accuracy of Medicare claims-based diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction: estimating positive predictive value on the basis of review of hospital records. Am. Heart J. 2004;148:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hlatky MA, et al. Use of medicare data to identify coronary heart disease outcomes in the Women’s health initiative. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 2014;7:157–162. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Birman-Deych E, et al. Accuracy of ICD-9-CM codes for identifying cardiovascular and stroke risk factors. Med. Care. 2005;43:480–485. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160417.39497.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. doi: 10.1093/biomet/70.1.41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Austin PC. Some Methods of Propensity‐score matching had superior performance to others: results of an empirical investigation and monte carlo simulations. Biomet. J. 2009;51:171–184. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200810488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin. Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kitsak M, et al. Tissue specificity of human disease module. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:35241. doi: 10.1038/srep35241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The human publicly available protein–protein interactome used in this study is freely available as a supplement to this manuscript (Supplementary Data 1). The unpublished binary human protein–protein interactions can be accessed at http://ccsb.dana-farber.org/interactome-data.html. The global predicted z-scores for 984 FDA-approved drugs and 23 types of cardiovascular events (diseases) via the network proximity approach are freely available in Supplementary Data 2. All other relevant data are available from the authors.