Abstract

Introduction

Physical fitness training after stroke is recommended in guidelines across the world, but evidence pertains mainly to ambulatory stroke survivors. Nonambulatory stroke survivors (FAC score ≤2) are at increased risk of recurrent stroke due to limited physical activity. This systematic review aimed to synthesize evidence regarding case fatality, effects, experiences, and feasibility of fitness training for nonambulatory stroke survivors.

Methods

Eight major databases were searched for any type of study design. Two independent reviewers selected studies, extracted data, and assessed study quality, using published tools. Random‐effects meta‐analysis was used. Following their separate analysis, qualitative and quantitative data were synthesized using a published framework.

Results

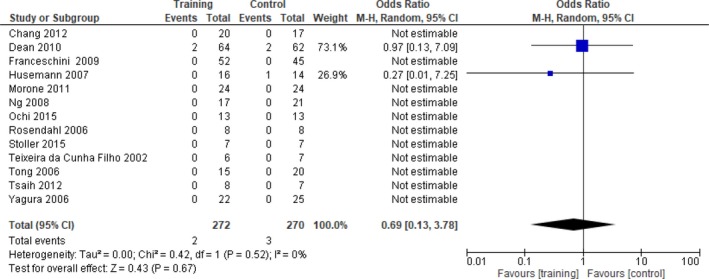

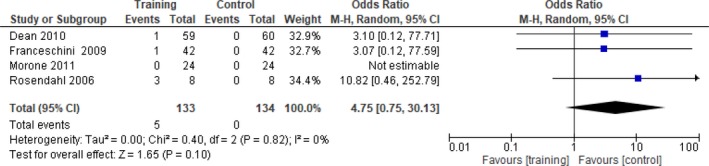

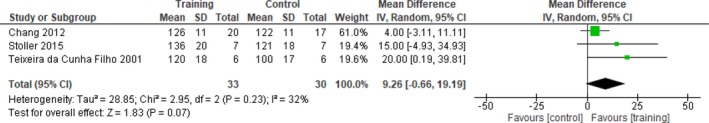

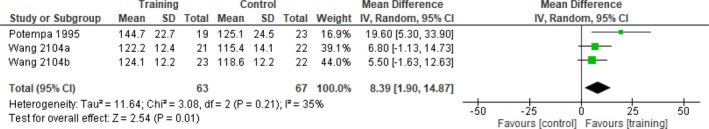

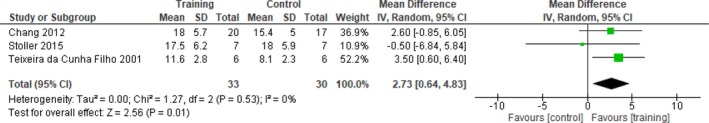

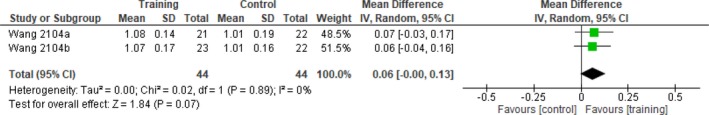

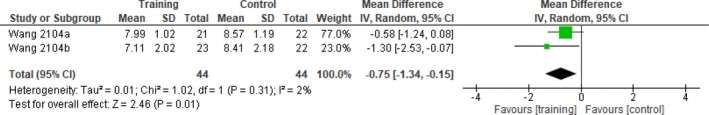

Of 13,614 records, 33 studies involving 910 nonambulatory participants met inclusion criteria. Most studies were of moderate quality. Interventions comprised assisted walking (25 studies), cycle ergometer training (5 studies), and other training (3 studies), mainly in acute settings. Case fatality did not differ between intervention (1.75%) and control (0.88%) groups (95% CI 0.13–3.78, p = 0.67). Compared with control interventions, assisted walking significantly improved: fat mass, peak heart rate, peak oxygen uptake and walking endurance, maximum walking speed, and mobility at intervention end, and walking endurance, balance, mobility, and independent walking at follow‐up. Cycle ergometry significantly improved peak heart rate, work load, peak ventilation, peak carbon dioxide production, HDL cholesterol, fasting insulin and fasting glucose, and independence at intervention end. Effectiveness of other training could not be established. There were insufficient qualitative data to draw conclusions about participants' experiences, but those reported were positive. There were few intervention‐related adverse events, and dropout rate ranged from 12 to 20%.

Conclusions

Findings suggest safety, effectiveness, and feasibility of adapted fitness training for screened nonambulatory stroke survivors. Further research needs to investigate the clinical and cost‐effectiveness as well as experiences of fitness training—especially for chronic stroke survivors in community settings.

Keywords: exercise, fitness, nonambulatory, rehabilitation, stroke, systematic review

1. INTRODUCTION

Fitness is often considerably reduced in stroke survivors compared with sedentary healthy controls, with marked reductions in muscle strength, power (Ivey, Macko, Ryan, & Hafer‐Macko, 2005), and oxygen uptake capacity (Saunders et al., 2016; Smith, Saunders, & Mead, 2012). Fitness is impaired along the entire stroke journey (Bernhardt, Chan, Nicola, & Collier, 2007; Egerton, Maxwell, & Granat, 2006; Kerr, Rowe, Esson, & Barber, 2016; Kunkel, Fitton, Burnett, & Ashburn, 2015; Moore et al., 2013), with ambulatory stroke survivors spending on average 81% of their day sedentary in their first year after stroke (Tieges et al., 2015). Reduced fitness after stroke is compounded by the increased energy cost of many activities; for example, walking typically requires around three times more energy than in healthy age‐matched controls (Platts, Rafferty, & Paul, 2006) because of motor impairments (Kramer, Johnson, Bernhardt, & Cumming, 2016). These compound other problems (Morris, Oliver, Kroll, Joice, & Williams, 2015, 2017; Morris, Oliver, Kroll, & Macgillivray, 2012; Nicholson et al., 2013, 2014) that make it difficult for stroke survivors to regain and maintain a level of fitness necessary for basic mobility (Macko et al., 2001)—a phenomenon known as “diminished physiological fitness reserve (McArdle, Katch, & Katch, 1996).” Reduced fitness adversely affects vascular risk factor profiles (Ivey, Hafer‐Macko, & Macko, 2006; Saunders et al., 2016), disability, and participation after stroke (Mayo et al., 1999). One of the top research priorities, selected by stroke survivors, carers, and health professionals, is to investigate the potential of fitness training to reduce recurrent stroke risk and improve function and quality of life (Pollock, St George, Fenton, & Firkins, 2012).

What is known already is that fitness training facilitates secondary prevention of cardiovascular morbidity (Garber et al., 2011), reduces disability, and improves walking (Saunders et al., 2016), quality of life (Carin‐Levy, Kendall, Young, & Mead, 2009), psychosocial functioning (Carin‐Levy et al., 2009), and adaptation to life after stroke (Reed, Harrington, Duggan, & Wood, 2010). This evidence underpins guidelines for community‐based exercise after stroke services in the UK (Best et al., 2010; Poltawski et al., 2013) and clinical guidelines across the world (Billinger et al., 2014; MacKay‐Lyons et al., 2013; Royal College of Physicians Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party, 2016; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2008, 2010; Stroke Foundation, 2017). These guidelines mainly pertain to ambulatory stroke survivors, however. There appears to be comparatively little research on fitness training for nonambulatory stroke survivors (Billinger et al., 2014; Saunders et al., 2016; i.e., those unable to walk at all or without physical assistance from at least one other person), who make up approximately 20% of the stroke population (Kwah, Harvey, Diong, & Herbert, 2013; Veerbeek, Van Wegen, Harmeling‐Van der Wel, & Kwakkel, 2011); 53 of the 58 studies in the Cochrane systematic review on fitness training after stroke (Saunders et al., 2016) involved ambulatory stroke survivors. Fitness training after stroke often involves walking (Saunders et al., 2016) and is therefore not suitable for most nonambulatory stroke survivors, who are thus disadvantaged by the lack of evidence‐based physical fitness training that is adapted to their mobility restrictions. As nonambulatory stroke survivors are inevitably more sedentary than their ambulatory counterparts, their risks associated with prolonged sitting (Rezende, Rodrigues Lopes, Rey‐López, Matsudo, & Luiz, 2014) are increased.

In summary, improving fitness in nonambulatory stroke survivors is a top priority, but there is a dearth of evidence‐based guidance to inform practice. To the knowledge of the authors, there is no published systematic review on this topic. The aim of this mixed‐methods systematic review and meta‐analysis was to synthesize published literature on physical fitness interventions for nonambulatory stroke survivors and evaluate the evidence for their effects on fitness, function, activity and participation, quality of life, acceptability, and feasibility.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Design

This review was designed as a mixed‐methods systematic review and meta‐analysis. The framework by Thomas, Ciliska, Dobbins and Micucci (2004), designed for synthesizing quantitative and qualitative evidence, was used to comprehensively integrate evidence on case fatality, effects, feasibility, and acceptability. The following sections describe the study eligibility criteria for this review.

2.2. Types of studies

Any type of quantitative, qualitative, or mixed‐methods (i.e., comprising a quantitative and qualitative element) study was included (e.g., randomized and nonrandomized, crossover, cohort, and case studies). For the analysis of case fatality and feasibility, data from all included studies were used. For the analysis of effects, only data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were used, given the increased risk of bias in non‐RCTs; for the analysis of acceptability, data from mixed‐methods and qualitative studies were used. Systematic reviews were excluded; however, their reference lists were searched to ensure all relevant studies were included. In order to have access to all relevant data, articles had to be full reports, published in English.

2.3. Types of participants

Only data pertaining to nonambulatory stroke survivors were included, as generalizing from ambulatory participants was considered inappropriate. Nonambulatory adult stroke survivors (age ≥18 years) were included, regardless of type and time since stroke, or any comorbidities. In studies where information about ambulatory status was absent or unclear, authors were contacted. Where it was not possible to obtain data relating to nonambulatory stroke survivors, studies were excluded. To the authors' knowledge, there is no standard definition for “nonambulatory.” The Functional Ambulation Category (FAC; Holden, Gill, Magliozzi, Nathan, & Piehl‐Baker, 1984) is a validated and widely used tool to describe walking ability after stroke. In this review, “nonambulatory” was defined as an FAC score ≤2, ranging from being completely unable to walk to being dependent on continuous/intermittent physical assistance of at least one person during walking, to help with balance or coordination (Holden et al., 1984).

2.4. Types of interventions

Improving cardiorespiratory fitness is crucial for secondary stroke prevention (O'Donnell et al., 2016) and therefore a key element in many fitness interventions after stroke (Saunders et al., 2016). Studies were therefore included if published intervention descriptions comprised structured activities aimed at improving health‐related fitness (Garber et al., 2011). The importance of skill‐related fitness was acknowledged; however, studies that focused exclusively on the latter (e.g., mirror‐box training to improve dexterity) were excluded. Similarly, voluntary muscle contraction was considered a key intervention ingredient. Therefore, studies were excluded if voluntary muscle contraction was not an essential component of the intervention (e.g., passive movement, electrical stimulation, or diet). Studies comprising only unstructured recreational or occupational physical activity were also excluded, as extracting information about dose would not be possible.

2.5. Types of setting

Interventions delivered in any type of setting (e.g., hospital, laboratory, community) were included, but they had to be land‐based.

2.6. Types of comparisons

Studies were not required to have a comparison, but those that did were only included if this provided information about the effects of the fitness intervention, that is, fitness training versus placebo, no intervention, usual care, or another intervention. Studies where a health‐related fitness intervention was compared to the same intervention plus an intervention not requiring active voluntary muscle contraction (e.g., a diet) were excluded. Data were compared between baseline and end of intervention, and between baseline and follow‐up (where provided).

2.7. Types of outcome measures

Quantitative studies were included if outcomes comprised at least one health‐related fitness component, as defined by the ACSM (American College of Sports Medicine, 2013), specified below). Studies were excluded if they only reported skill‐related fitness outcomes. Outcomes were categorized into International Classification of Disability and Functioning (ICF; World Health Organization, 2001) domains where possible, to enable comparison to recommended stroke datasets (Geyh et al., 2004; Silva et al., 2015).

Primary outcomes comprised the following:

Case fatality

Health‐related fitness outcomes (American College of Sports Medicine, 2013), that is, measures of cardiovascular endurance (e.g., 6‐minute walk test), body composition (e.g., fat mass), muscle strength (e.g., Motricity Index) and endurance, flexibility (e.g., range of motion), and measures of cardiorespiratory function (e.g., blood pressure) and metabolic function (e.g., blood glucose).

Secondary outcomes comprised the following:

Skill‐related fitness outcomes (ACSM, 2013), that is, measures of agility (e.g., Rivermead Mobility Index), coordination (e.g., Fugl‐Meyer), balance (e.g., Berg Balance Scale), power (e.g., Nottingham power rig), reaction time, and speed (e.g., walking speed).

Stroke‐related general measures of function (i.e., body function (e.g., Canadian Neurological Scale), sensory function (e.g., hemispatial neglect), mobility (e.g., Functional Ambulation Category), movement‐related functions (e.g., Trunk Control Test), mental functions (e.g., Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale)), activities and participation (e.g., Stroke Impact Scale), and quality of life (e.g., the Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale).

Feasibility, operationalized as the number of patients assessed for eligibility and those randomized (or allocated otherwise to an intervention), attendance, number of dropouts and adverse events, and acceptability of the intervention, reported by study participants. Review authors extracted data on dropouts in the period between intervention start and end of study and then categorized these as: possibly intervention‐related, general health‐related, logistics‐related, and refusal to participate—if this could be deduced from the text. Otherwise, dropouts were categorized as unknown or not reported. These data were extracted from all studies included in this review.

2.8. Search terms and databases

A combination of controlled Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free‐text terms relating to the key search terms of “stroke,” “physical activity,” and “non‐ambulatory” were used to search the following electronic databases from inception until 31 July 2016: AMED, CINAHL and Medline in EBSCOhost, PEDro, Web of Science, Cochrane Database, PubMed, and Embase. Search terms were modified for each database (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search strategy for PubMed (adapted for each database)

| PubMed (PubMed Central) |

|---|

| ((((((((((((((((“stroke/brain”[All Fields] OR “stroke/cerebral”[All Fields]) OR “stroke/cerebrovascular”[All Fields]) OR “stroke/cerebrovascular accident”[All Fields]) OR “stroke/cva”[All Fields]) OR “stroke/edema”[All Fields]) OR “stroke/embolism”[All Fields]) OR “stroke/hemiparesis”[All Fields]) OR “stroke/hemiplegia”[All Fields]) OR “stroke/infarcted”[All Fields]) OR “stroke/infarction”[All Fields]) OR “stroke/ischemia”[All Fields]) OR “stroke/ischemic”[All Fields]) OR “stroke/rehabilitation”[All Fields]) OR “stroke/therapy”[All Fields]) OR (“stroke”[MeSH Terms] OR “stroke”[All Fields])) AND (((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((“physical activity”[All Fields] OR “physical activity/exercise”[All Fields]) OR “physical activity/fitness”[All Fields]) OR “physical activity/increased”[All Fields]) OR “physical activity/participation”[All Fields]) OR “physical activity/rehabilitation”[All Fields]) OR “physical activity/sport”[All Fields]) OR (“motor activity”[MeSH Terms] OR (“motor”[All Fields] AND “activity”[All Fields]) OR “motor activity”[All Fields] OR (“physical”[All Fields] AND “activity”[All Fields]) OR “physical activity”[All Fields])) OR “chair based”[All Fields]) OR “chair based yoga”[All Fields]) OR (chair[All Fields] AND based[All Fields])) OR “exercise”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/activities”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/activity”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/aerobic”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/circuit”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/fitness”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/fitness programs”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/group”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/leisure”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/muscle”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/muscle contraction”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/physical”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/physical activity”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/physical therapy”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/rehabilitation”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/rehabilitation programs”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/sport”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/sport activity”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/sports”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/strength”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/strength training”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/stretch”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/stretching”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/therapy”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/therapy interventions”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/therapy programs”[All Fields]) OR “exercise/treatment”[All Fields])) AND ((((((((((((“non ambulatory”[All Fields] OR “non ambulatory activities”[All Fields]) OR “non ambulatory activity”[All Fields]) OR “non ambulatory hemiparetic patients”[All Fields]) OR “non ambulatory individuals”[All Fields]) OR “non ambulatory participants”[All Fields]) OR “non ambulatory persons”[All Fields]) OR “non ambulatory status”[All Fields]) OR “non ambulatory stroke”[All Fields]) OR “non ambulatory stroke patients”[All Fields]) OR “chair bound”[All Fields]) OR “chair bound patients”[All Fields]) OR “chair bound persons”[All Fields]) |

2.9. Study selection

One review author (ML) screened all citations identified, using the predetermined inclusion criteria listed above, discarding those that were clearly not relevant. Two review authors (ML and FvW) independently screened abstracts of all selected titles using the same criteria, retaining those that were clearly or possibly relevant. The same process was undertaken for full‐text articles. A third review author (DS) was available to facilitate agreement if required. Reference lists of studies included and relevant reviews identified in the search were also screened.

2.10. Data collection process and data items

Data from the included studies were extracted independently by two review authors (ML and FvW) and cross‐checked for any discrepancies. A third review author (DS) was available if required. Data extracted covered the ACSM FITT principles (ACSM, 2013) and CERT criteria (Slade et al., 2016) and included the following: study design, inclusion/exclusion criteria, age, time poststroke, intervention frequency, intensity, type, time, materials, provider, delivery, setting, dosage, adherence, motivational strategies, home program, tailoring, dropouts and adverse events, and outcomes and experiences of the intervention.

2.11. Quality assessment

Quantitative studies were assessed using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) tool (Thomas et al., 2004), which is designed for randomized and nonrandomized studies (Deeks et al., 2003) and has content and construct validity (Jackson & Waters, 2005; Thomas et al., 2004), “fair” interrater agreement for singular domains, and “excellent” agreement for final ratings (Armijo‐Olivo, Stiles, Hagen, Biondo, & Cummings, 2012). The overall global rating (“strong,” “moderate,” or “weak”) is based on the tally of individual component scores. Mixed‐methods studies were assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT; Pluye, Gagnon, Griffiths, & Johnson‐Lafleur, 2009; Pluye et al., 2011). Its interrater reliability ranges from moderate to perfect; however, its validity has not been assessed yet (Pace et al., 2012). Scores are given for the number of criteria met per domain, while an overall score is given at the level of the lowest domain score. Qualitative studies were to be assessed with the critical review form developed by the McMaster University Occupational Therapy Evidence‐Based Practice Research Group (version 2.0; Letts et al., 2007). Each study was assessed independently by two review authors (ML and FvW), after which findings were discussed. A third review author (DS) was available as arbitrator. As the aim of this review was to synthesize all published quantitative and qualitative data from a body of literature that was anticipated to be limited, no studies were excluded on the basis of their methodological quality. However, study quality informed the discussion on the strength of the evidence, and recommendations for further research and implementation.

2.12. Data analysis and synthesis

Only data pertaining to nonambulatory stroke survivors were included in this review, as generalizing from ambulatory participants was considered inappropriate. In studies where data on nonambulatory stroke survivors had to be extracted from mixed populations, review authors (ML, FvW) independently extracted and analyzed data, analyzed additional data supplied by study authors, or included additional data analyzed by study authors, as required (as indicated in Tables 4, 5, 6, 7). Given the small sample sizes of such subgroups, only descriptive data were presented in this review. Interventions were grouped into clinically relevant categories of assisted walking training, cycle ergometer training, or “other” training.

Table 4.

Demographic data and inclusion/exclusion criteria of included studies

| Author (year) | Number of non‐ambulatory stroke participants (% of study participants) | Age (years) of study participantsMean (SD) (unless stated otherwise) | Time since stroke of study participantsMean (SD) (unless stated otherwise) | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batcho (2013)a | Int.: 6 (12%) | Int.: 60.5 (45–85)b | Int.: 18.4 (13–44) monthsb | 1. Having stroke at least 6 months prior to inclusion, 2. Minimal ambulatory capacity with supervision and/or assistive device, 3. No major cognitive deficit that could prevent completion of a self‐reported questionnaire (MMSE score ≥24). | NR |

| Chang (2012) | Int.: 20 (100%)Cont.: 17 (100%) | Int.: 55.5 (12.0)Cont.: 59.7 (12.1) | Int.: 16.1 (4.9) daysCont.: 18.2 (5.0) days | 1. First‐ever stroke, 2. Stroke onset within 1 month, 3. Supratentorial lesion, 4. Age >20 years and <65 years, 5. FAC< 2, 6. Ability to cooperate during exercise testing. | 1. Absolute and relative contraindications to exercise testing as per ACSM, 2. contraindications for Lokomat therapy, 3. Musculoskeletal disease involving the lower limbs, e.g., severe painful arthritis, osteoporosis, or joint contracture and other neurological diseases. |

| Cho (2015) | Group 1: 13 (100%)Group 2: 7 (100%) | Group 1: 55.3 (11.9)Group 2: 55.4 (15.3) | Group 1: 15.1 (8.7) monthsGroup 2: 13.4 (6.7) months | 1. Time post stroke >6 months, 2. FAC <2, 3. Independent ambulation before stroke, 4. Capability of understanding and executing RAGT, 5. An absence of other orthopaedic or neurological problems in the lower extremities. | 1. Weight >120 kg. 2. Femoral length <35 cm or femoral length >47 cm. 3. History of lower extremity fracture after stroke. 4. Instability or subluxation of the hip joint. 5. Pressure ulcers on hips or lower extremities. 6. Any underlying disease preventing execution of RAGT. |

| Dean (2010) | Int.: 64 (100%)Cont.: 62 (100%) | Int.: 70 (9)Cont.: 71 (9) | Int.: 18 (8) daysCont.: 18 (7) days | 1. Within 28 days of 1st stroke, 2. Aged 50–85 years, 3. Clinically diagnosed with hemiplegia or hemiparesis, 4. Non‐ambulatory, defined as Item 5 (walking) score 0 or 1 on MAS. | 1. Clinically evident brainstem signs, 2. Severe cognitive and/or language deficits, unable to follow instructions, 3. Unstable cardiac status, 4. Pre‐morbid conditions that precluded rehabilitation. |

| Demers (2015)c | Int.: 5 (31%) | Int.: 71 (47–74)b | Int.: 2 (1–4) monthsb | 1. Stable medical condition, regardless of co‐morbidities or medication. | 1. Severe motor apraxia, 2. Severe mixed aphasia, 3. Tetraplegia, 4. Poor tolerance to group setting, 5. Significant behavioural problems, 6. Unable to tolerate at least 2, 45‐min treatment sessions per day. |

| Franceschini (2009) | Int.: 52 (100%)Cont.: 45 (100%) | Int.: 65.5 (12.2)Cont.: 70.9 (11.8) | Int.:16.7 (9.8) daysCont.: 14.4 (7.3) days | 1. Time post stroke < 45 days, 2. Able to control sitting position on rigid surface with legs hanging freely and without arm support for at least 30 s, 3. Able to control trunk in upright position even with help of upper extremities gripping a fixed support or other aid, 4. No LL spasticity (Ashworth scale ≤1), 5. Stable cardiovascular condition with a low risk for vigorous exercise (ACSM Class B). | 1. Significant pre‐stroke disability (modified Rankin Scale ≥2), 2. Significant pre‐stroke gait disability (Walking Handicap Scale ≥2), 3. Orthopaedic or other pre‐stroke disorders causing a gait limitation, 4. Mild gait impairment at time of enrolment (ability to walk without aids for at least 3 m or for more than 6 m with the aid of a cane or tripod,. 5. Previous treadmill training, 6. ACSM Class C or D exercise risk or New York Heart Association classification system Class III or IV risk. |

| Hesse (1994) | Int.: 9 (100%) | Int.: 56.7 (31–79) | Int.: 129 (54–414) days | NR | NR |

| Hesse (1995) | Int.: 7 (100%) | Int.: 60.3 (52–72) | Int.: 176.8 (91–362) days | NR | 1. Additional neurological and/or orthopaedic deficits that impaired ambulation, 2. Heart Failure classified as greater than New York Heart Association grade 2. |

| Hesse (2010) | Case study: Int.: 1 (100%) | Case study: Int.: 72 | Case study: Int.: 5 weeks | NR | NR |

| Hesse (2012) | Int.: 15 (100%)Cont.: 15 (100%) | Int.: 63.7 (9.4)Cont.: 66.4 (11.9) | Int.: 5.7 (2.3) weeksCont.: 5.1 (1.6) weeks | 1. Age <80 years, 2. First‐time supratentorial stroke with time post stroke <10 weeks, 3. Wheelchair‐mobilised and partially independent in basic activities of living (Barthel Index 30–55 out of 100), 4. Able to sit at edge of bed with hands holding on and feet placed on floor and able to stand for short period with hands holding on, 5. Requiring continuous or intermittent help carrying weight and with balance during gait (FAC 1–2), 6. No severe lower‐limb spasticity, joints must reach neutral position in standing frame, 7. No severe heart disease limiting participation according to cardiology exam including a 12‐lead ECG, 8. No other neurological or orthopaedic disease impairing repetitive gait practice, 9. No severe cognitive or communicative impairment. | NR |

| Husemann (2007) | Int.: 17 (100%)Cont.: 15 (100%) | Int.: 60(13)Cont.: 57(11) | Int.: 79(56) daysCont.: 89(61) days | 1. No prior stroke, 2. No other neurological or orthopaedic disorder, 3. Independent ambulation prior to stroke, 4. No severe medical illness, 5. Severe lower extremity hemiparesis (Lower extremity muscle strength MRC grade ≤3 in >2 muscle groups), 6. FAC ≤1 7. Time post stroke 28–200 days. | NR |

| Lennon (2008)c | Int.: 4 (17%)Cont.: 4 (17%) | Int.: 59.0(10.3)dCont.: 60.5(10.0)d | Int.: 237.3 (110.7) weeksdCont.: 245.3 (169.8) weeksd | 1. Time post stroke >1 year, 2. Stroke confirmed by MRI/ CT scan, 2. Age >18 years, 3. Irrespective of ambulatory capacity. | 1. O2 dependence, 2. Angina, 3. Unstable cardiac conditions, 4. Uncontrolled diabetes, 5. Major medical condition, 6. Claudication, 7. Febrile illness, 8. Cognitive impairment, 9. Beta blocker medication. |

| Leroux (2005) | Int.: 20 (100%) | Int.: 67.6 (10.0) | Int.: 5.5 (6.3) years | 1. Stroke resulting in hemiplegia or hemiparesis, 2. Time post stroke ≥ 6 months, 3. Fully discharged from rehabilitation, 4. Written approval from primary care physician, 5. Complete the CJCS physical activity questionnaire (modified Par‐Q form). | 1. Previous participation in the exercise class at the CJCS, 2. Any medical conditions that would severely limit participation in the exercise program or outcome assessments. |

| Mayr (2007)a | Int. ABA: 7 (88%)Int. BAB: 5 (63%) | Int. ABA: 65 (44–87)bInt. BAB: 67 (57–78)b | Int. ABA: 2 (1–10) monthsbInt. BAB: 1.5 (1–5) monthsb | NR | NR |

| Mehrholz (2006) | Int.: 6 (100%) | Int.: 54.5 (41–67)b | Int.: 6 (3–12) weeksb | 1. Hemiparesis due to 1st stroke of middle cerebral artery or hemispheric haemorrhagic stroke, 2. Able to stand with assistance for at least 10s, 3. Able to walk 15 m with therapist, 4. FAC= 2 | 1. Osteoporosis, 2. Ankle contracture, 3. Modified Tardieu and Ashworth Scale 2 + (increased muscle tone ankle, knee or hip), 4.Neurological symptoms e.g., aphasia. |

| Morone (2011) | Int. 1: 12 (100%)Int. 2: 12 (100%)Cont. 1: 12 (100%)Cont. 2: 12 (100%) | Int. 1: 55.58 ± 13.35Int. 2: 68.33 ± 9.11Cont. 1: 60.17 ± 9.59Cont. 2: 62.92 ± 17.43 | Int. 1: 16.25 ± 11.33 daysInt. 2: 21.92 ± 10.72 daysCont. 1: 20.00 ± 12.76 daysCont. 2: 20.00 ± 15.68 days | 1. Hemiplegia/hemiparesis in the subacute phase, 2. Significant gait deficits (FAC < 3) caused by a first‐ever stroke, 3. Lesions confirmed by CT or MRI, 4. Age between 18–80 years. | 1. Subarachnoid haemorrhage, 2. Sequelae of prior stroke, 3. Other chronic disabling pathologies, 4. Orthopaedic injuries that could impair locomotion, 5. Spasticity limiting lower extremity, i.e., ROM less than 80%, 6. Sacral skin lesions, 7. MMSE score < 24 8. Hemispatial neglect. |

| Ng (2008) | Int. 1: 17 (100%)Int. 2: 16 (100%)Cont.: 21 (100%) | Int. 1: 66.6 (11.3)Int. 2: 62.0 (10.0)Cont.: 73.4 (11.5) | Int. 1: 2.7 (1.2) weeksInt. 2: 2.3 (1.1) weeksCont.: 2.5 (1.2) weeks | 1. Diagnosis of ischaemic brain injury or intracerebral haemorrhage by MRI or CT, 2. Time post stroke <6 weeks, 3. Sufficient cognition to follow simple instructions and understand study content and purpose (MMSE >21), 4. Ability to stand upright, supported or unsupported, for 1 minute, 5. Significant gait deficit (FAC <3), 6. No skin allergy. | 1. Recurrent stroke or other neurological deficit affecting ambulation ability, 2. Any additional medical or psychological condition affecting ability to comply with study protocol, 3. Aphasia or a cognitive deficit with inability to follow two consecutive step commands, 4. Severe hip, knee or ankle contracture or orthopaedic problem affecting ambulation that would preclude passive ROM of paretic leg. |

| Ochi (2015) | Int.: 13 (100%)Cont.: 13 (100%) | Int.: 61.8 (7.5)Cont.: 65.5 (12.1) | Int.: 22.9 (7.4) daysCont.: 26.1 (8.0) days | 1. First‐ever stroke with a unilateral cerebral hemispheric lesion confirmed by CT or MRI, 2. Age 40–85 years, 3. Time post stroke < 5 weeks, 4. Severe paralysis of the LL (Brunnstrom's stage < grade III, 5. Non‐ambulator, defined as FAC ≤2, 6. Independent walking before stroke. | 1. Height <145 or >180 cm, 2. Body weight >100 kg, 3. Marked limitation in LL ROM, 4. Severe cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, or musculoskeletal disease, 5. Difficulty communicating. |

| Plummer (2007) | Int.: 1 (14%) | Int.: 73 | Int.: 6 months | 1. Time post stroke 3–7 months, 2. Residual LL paresis, 3. Able to sit unsupported for 30 seconds, 4. Follow a 3 step command, 5. Able to walk at least 10 ft with maximum AO1, 6. Self‐selected gait speed <0.8 m/s. | 1. Dependent in self‐care/lived in nursing home prior to stroke, 2. Unable to ambulate ≥150 ft. prior to stroke, 3. Serious cardiac conditions, 4. Serious COPD, 5. Supplemental O2 dependence, 6. Severe WB pain, 7. Pre‐existing neurological disease, 8. Dementia, 9. Previous stroke with existing neurological deficits,10. History of major head trauma, 11. LL amputation, 12. Non‐healing LL ulcers, 13. Renal dialysis or end stage liver disease, 14. Legal blindness or severe visual impairment, 15. History of significant psychiatric illness, 16. Life expectancy <1 year, 17. Severe arthritis or orthopaedic problems limiting LL passive ROM, 18. History of alcoholism or drug abuse, 19. History of DVT or pulmonary embolism within 6 months, 20. Uncontrollable diabetes with recent weight loss, 21. Diabetic coma or frequent insulin reactions, 22. Severe sustained hypertension with systolic BP >180 mmHg and diastolic BP >100 mmHg. |

| Potempa (1995) | Int.: 19 (100%)Cont.: 23 (100%) | Not reported as int/cont groups | NR | 1. Aged 21–77 years, 2. Time post hemispheric stroke >6 months, 3. Medically stable, 4. Completed rehabilitation. | 1. Brain stem lesions, 2. Disorders that preclude maximal exercise testing or confound the measurement of maximal exercise parameters. |

| Richards (1993) | Int.: 10 (100%)Cont. 1: 8 (100%)Cont. 2: 9 (100%) | Int.: 69.6 (7.4)Cont. 1: 67.3 (11.2)Cont. 2: 70.3 (7.3) | 0–7 days | 1. Live within 50 km of study site, 2. Age 40–80 years, 3. Time post 1st stroke <7 days, 4. Clinically identifiable MCA syndrome of thromboembolic origin involving subcortical structures confirmed by CT, 5. Under medical supervision of study neurologist. | 1. Other neurological conditions, 2. Major medical problem that had or would incapacitate functional capacity or interfere with rehabilitation. |

| Rosendahl (2006)a | Int. 1: Exercise + diet supplement: 4 (8%)Cont. 1: Sitting + diet supplement: 7 14%)Int. 2: Exercise + placebo: 8 (18%)Cont. 2: Sitting + placebo: 8 (16%) | Int. 1: Exercise + diet supplement: 82 (74–92)bCont. 1: Sitting + diet supplement: 79 (65–86)bInt. 2: Exercise + placebo: 88 (77–90)bCont. 2: Sitting + placebo: 84.5 (68–90)b | NR | 1. Age ≥65 years, 2. Dependent on assistance from a person in ≥1 personal activity of daily living according to Katz Index, 3. Able to stand up from chair with armrests with help from no more than one person, 4.MMSE ≥10. 5. Approval from physician. | NR |

| Shea (2014) | Int.: 1 (100%) | Int.: 67 | Int.: 8 months | NR | NR |

| Stoller (2015) | Int.: 7 (100%)Cont.: 7 (100%) | Int.: 57 (12)Cont.: 63 (13) | Int.: 52 (42) daysCont.: 45 (30) days | 1. Clinical diagnosis of first‐ever stroke, 2. Time post stroke < 20w,3. Age > 18 years, 4. FAC <3, 5. Ability to understand procedures and provide informed consent. | 1. Contraindications for cardiopulmonary exercise testing (ACSM), 2. Contraindications for robot‐assisted treadmill exercise according to device manufacturer, 3. Concurrent neurological disease) 4. Concurrent pulmonary disease, 5. Dementia. |

| Teixeira da Cunha Filho (2001) | Int.: 6 (100%)Cont.: 6 (100%) | Int.: 57.83 (5.56)Cont.: 59.67 (13.58) | Int.: 15.67 (7.66) daysCont.: 14.33 (6.06) days | 1. Time post stroke < 6 weeks, diagnosis based on clinical presentation or MRI, 2. Significant gait deficit i.e., speed ≤36 m/min and FAC ≤2, 3. MMSE ≥21, 4. Able to stand with or without assistance and take ≥1 step with or without assistance. | 1. Co‐morbidity or disability other than hemiparesis that would preclude gait training, 2. MI within 4 weeks, 3. Uncontrolled health condition that contraindicates exercise, e.g., uncontrolled diabetes, 4. Severe lower extremity joint disease or rheumatoid arthritis, 5. Body weight >110 kg, 6. MMSE <21. |

| Teixeira da Cunha Filho (2002) | Int.: 6 (100%)Cont.: 7 (100%) | Int.: 57.80 (5.50)Cont.: 58.90 (12.90) | Int.: 15.70 (7.70) daysCont.: 19.00 (12.70) days | See Teixeira da Cunha Filho (2001). Also: 1. Stable medical condition allowing participation in exercise | See Teixeira da Cunha Filho (2001) Also:1. Cardiac bypass surgery with complications, 2. History of bilateral stroke. |

| Tong (2006) | Int. 1: 15 (100%)Int. 2: 15 (100%)Cont.: 20 (100%) | Int. 1: 66.1 (9.9)Int. 2: 61.8 (10.8)Cont.: 71.4 (14.0) | Int. 1: 2.7 (1.3) weeksInt. 2: 2.3 (1.0) weeksCont.: 2.7 (1.2) weeks | 1. Diagnosis of ischaemic brain injury or intracerebral haemorrhage by MRI or CT, 2. Time post stroke< 6w, 3. Sufficient cognition to follow simple instructions and understand the study (MMSE >21), 4. Able to stand upright, supported/ unsupported for 1 minute, 4. Significant gait deficit (FAC <3), 5. No skin allergy to electrical stimulation. | 1. Recurrent stroke or other neurological deficit affecting ambulation, 2. Any additional medical or psychological condition affecting ability to comply with study protocol, 3. Aphasia or a cognitive deficit with inability to follow two consecutive step commands, 4. Severe hip, knee or ankle contracture that would preclude LL passive ROM. |

| Tsaih (2012)a | Int.: 8 (32%)Cont.: 7 (28%) | Int.: 72.5 (45–90)bCont.: 75 (54–89)b | Data not provided by authors | 1. Ambulation challenged but judged to be able to regain walking after treatment, 2. Clarity of consciousness and ability to follow one step commands, 3. Walking speed < 37 m/min, 4. Ability to stand with walking aids or slight assistance of one, 5. Knee extensor muscle strength > grade III, 6. Knee flexion contracture <20°, 7. Ability to sit independently > 2 min | 1. Any exercise contraindications, 2. Uncontrolled BP. |

| Vidoni (2008) | Int.: 1 (100%) | Int.: 61 | Int.: ≥5 years | 1. Time post stroke ≥ 6 months, 2. Able to transfer sit‐ stand with minimal assistance, 3. Unable to walk independently, 4. Without language or cognitive deficits that would impair informed consent, 5. Without a medical condition that would prevent safe participation in an exercise programme. | NR |

| Wang (2014a) | Int.: 24 (100%)Cont.: 24 (100%) | Int.: 57 (6.8)Cont.: 55 (11.5) | Int.: 30 (10.2) daysCont.: 36 ± 12.1 days | 1. Time post stroke 2–6 week, 2. Age 45–75 years, 3. Unable to walk with any walk aid, 4. Severely impaired; affected leg score≤ 3 on the Chedoke‐McMaster Stroke Assessment scale, 5. Cardiovascular stable, 6. No orthopaedic disease to preclude ergometer exercise training, 7. Not taking medication that might significantly alter heart rate, 8. Able to understand study information. | 1. Subarachnoid haemorrhage, 2. TIA, 3. Severe cerebral oedema, 4. O2 dependence, 5. Angina, 6. Unstable cardiac condition, 7. Peripheral arterial occlusive disease, 8. Abnormal high fever ,9. BP >200/110 mmHg, 10. Dementia, 11. Aphasia operationally defined as incapacity to follow two‐point commands, 12. Untreated major depression. 13.Other medical conditions precluding participation in exercise training. |

| Wang (2014b) | Int.: 27 (100%)Cont.: 27 (100%) | Int.: 54 (7.2)Cont.: 52 (12.1) | Int.: 109 (31.2) daysCont.: 86 (19.2) days | 1. Time post stroke 1–6 months, 2. Stroke confirmed by CT or MRI, 3. Age >45 years, 4. Severely impaired; affected leg ≤3 or less on Chedoke–McMaster Stroke Assessment scale, 5. Unable to walk even with aids, 6. Unaffected leg able to move against normal resistance, 7. Fasting glucose level < than 7 mmol/L, 7. No physician‐diagnosed diabetes, 8. In stroke unit or neurology department, 9. Never using medications that may significantly alter HR and blood glucose level, 10. Able to understand study information. | 1. Subarachnoid haemorrhage, 2. TIA, 3. Severe cerebral oedema, 4. O2 dependence, 5. Angina, 6. Unstable cardiac conditions, 7. Peripheral arterial occlusive disease, 8. Abnormal high fever, 9. Severe pneumonia, 10. BP> 200/110 mm Hg, 11.Dementia, 12. Aphasia operationally defined as incapacity to follow two‐point commands, 13. Untreated major depression, 14. Other medical conditions precluding participation in exercise training. |

| White (2013)a | Int.: 4 (18%) | Int.: 63 (57–80)b | Int.: 22 (9–84) monthsb | 1. Diagnosis of stroke, 2. Community dwelling, 3. Not currently accessing other rehabilitation services. | 1. Severe cognitive or language impairment. |

| Yagura (2006) | Int.: 22 (100%)Cont.: 25 (100%) | Int.: 62.9 (7.4)Cont.: 59.3 (5.7) | Int.: 57.0 (11.0) daysCont.: 58.4 (24.4) days | 1. Time post stroke < 3 months, 2. Inpatient, 3. Requiring physical assistance with gait after 4 weeks of inpatient rehabilitation. | 1. Age >80 years, 2. Impaired cognitive function, 3. Previous stroke, 4. Dependence in ADLs prior to stroke, 5. History of MI within 1 year, 6. Uncontrolled hypertension, 7. Symptomatic orthostatic hypotension, 8. Uncontrolled rate arterial fibrillation. |

| Yang (2014)a | Int.: 1 (7%)Cont.: 1 (7%) | Int.: 56Cont.: 44 | Int.: 29 monthsCont.: 6 months | 1. First‐ever stroke, 2. Time post stroke 3 months–3 years, 3. Unilateral hemiplegia, 4. Age 18–70 years, 5. Ability to walk 10 m with or without assistance, 6. Scores of three levels of consciousness items in the NIHSS = 0. | 1. Patients with aphasia who could not follow instructions, 2. Blindness or severe visual impairments that prohibit seeing the faceplate, 3. Musculoskeletal disorders, 4. Cardiac disorders, 5.Peripheral neuropathy that could potentially interfere with study. |

ACSM: American College of Sports Medicine. ADL: Activities of Daily Living. AO1/2: Assistance of one/two people. BP: Blood Pressure. CJCS: Cummings Jewish Centre for Seniors. Cont.: Control group. COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. CT: computed tomography scan. DVT: Deep Vein Thrombosis. ECG: Electrocardiogram. FAC: Functional Ambulation Category. Int.: Intervention group. LL: lower limb. MAS: Motor Assessment Scale for Stroke, MCA: Middle cerebral artery, MI: Myocardial Infarction. MMSE: Mini Mental Scale Examination. MRC: Medical Research Council Scale. MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging. NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. NR: Not Reported. ROM: Range of Movement. SD: Standard Deviation. TIA: transient ischaemic attack. RAGT: Robot Assisted Gait Training. RATE: Robot Assisted Treadmill Exercise. WB: Weight Bearing.

All data were extracted from publications, except in cases indicated by: aData supplied by author, analysed by review authors (ML, FvW). bMedian (range). cAnalysed data supplied by the author. dData from all study participants including those who were not non‐ambulatory after stroke, where data from the latter were not available. NR data not reported by study authors.

Table 5.

Overview of intervention parameters in intervention groups (and control groups where included)

| Author (year) design | Intervention parameters | Intervention | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Batcho (2013)Cohort study

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

3× p/w, 3 months Slightly breathless, but still able to talk (Moderate) Brisk Walking, defined as walking at ‘a pace faster than normal that leaves the individual slightly breathless but still able to converse' (p. 855), NRCommunity sport centre: group format Physiotherapist Attendance record Personalised feedback after each session NR |

N/A | ||

Chang (2012)RCT

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

2× p/d, 5× p/w, 2 w NR. Initial BWS 40%, gradually reduced, speed starting at 1.2 km/hr, gradually increased to 2.6 km/hr. BWS Lokomata + Conventional PT (NDT) + UC BWS Lokomat = 40 min, Conventional PT = 60 min Stroke rehabilitation unit Therapist NR Visual feedback to encourage movement efficiency NR |

2× p/d, 5× p/w, 2 w NR Conventional PT (NDT) + UCConventional PT = 40 min, Conventional PT = 60 min Stroke rehabilitation unit Therapist NR NR NR |

||

Cho (2015)Randomised cross‐over trial

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

BWS Lokomat: 3× p/w, 4w. PT: 5× p/w, 8w NR. Initial guidance force at hip and knee at 100%, gradually reduced, initial BWS 40%, gradually reduced, self‐selected speed between 1.0–1.8 km/hr. BWS Lokomata (w 1–4) + PT (w 1–8) BWS Lokomat = 30 min, PT = 30 min Rehabilitation Centre NR NR NR NR |

BWS Lokomat: 3× p/w, 4w. PT: 5 p/w, 8w NR. Initial guidance force at hip and knee at 100%, gradually reduced, initial BWS 40%, gradually reduced, self‐selected speed between 1.0–1.8 km/hr. BWS Lokomat (w 5–8) + PT (w 1–8) BWS Lokomat = 30 min, PT = 30 min Rehabilitation Centre NR NR NR NR |

||

Dean (2010)RCT

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

5× p/w until independent walking or discharged NR. BWS gradually reduced. BWSTT + LL therapies BWSTT <30 min, LL therapies <60 min Rehabilitation unit Physiotherapist Attendance record NR NR |

5× p/w until independent walking or discharged NR Assisted overground walking + LL therapies Overground walking ,< 30 min, LL therapies <60 min Rehabilitation unit Physiotherapist Attendance record NR NR |

||

| Demers (2015)Mixed methodsDance | Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

2× p/w, 4w Moderate Dance (Jazz & Merengue) + UC 45 min Rehabilitation hospital, group format Occupational Therapist Attendance record Performance in front of small audience NR |

N/A | ||

Franceschini (2009)RCT

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

Total 20 sessions, 5× p/w completed by w 5 NR. BWS 40% max., gradually reduced. Speed gradually increased. BWSTT + UC+ additional neuropsychological and occupational therapy input as required BWSTT = 20 min (net training), UC = 40 min Rehabilitation centre Physiotherapist NR NR NR |

Total 20 sessions, 5× p/w completed by w 5 NR Overground gait training combined with UC+ additional neuropsychological and occupational therapy input as required 60 min Rehabilitation centre Physiotherapist NR NR NR |

||

Hesse (1994)Cohort study

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

5× p/w, 5w NR. Mean BWS 31.2% initially, gradually reduced. Mean speed 0.09 m/s initially, gradually increased. BWSTT + UC BWSTT = 15 min initially, increasing to 30 min Rehabilitation clinic Therapist NR NR NR |

N/A | ||

Hesse (1995)Case study

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

5× p/w, 9w (each block lasting 3 w) NR. BWS 30% initially, gradually reduced. Speed 0.07 m/s initially, gradually increased. [BWSTT – PT – BWSTT] + UC BWSTT = 30 min, PT = 45 min Inpatient hospital Therapist NR NR NR |

N/A | ||

Hesse (2010)Case study within observational study

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

5× p/w, 5w Max. HR 120 bpm. BWS max. 30%, reduced to 10%. Speed initially 0.25 m/s, increased to 0.33 m/s. Total steps/ session in 1st week = 600. BWS G‐EO Systems Robotb gait training + stair climbing Gait robotic training = 25 to 30 min (net training time approx. 15 min), Stair climbing = 5 to 8 min NR Physiotherapist NR NR NR |

N/A | ||

Hesse (2012)Non‐randomised clinical trial

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

5× p/w, 4w NR. Reps. per session: walking steps ≥300, stair climbing steps ≥50 BWS G‐EO Systems Robotb gait & stair climbing trainer + over ground gait & stair climbing + UC BWS robot gait and stair climbing training = 30 min (net 15–20 min). Over ground training = 30 min Rehabilitation centre Physiotherapist NR NR NR |

5× p/w, 4w NR Over ground gait & stair climbing + task specific repetitive movements, tone inhibiting manoeuvres + UC 60 min Rehabilitation centre Physiotherapist NR NR NR |

||

Husemann (2007)RCT

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

5× p/w, 4 w NR. Max 30% BWS, gradually reduced. Speed: max. tolerated BWS Lokomata + UC BWSTT = 60 min (net time 30 min) + conventional PT = 20 min Hospital Physiotherapist NR NR NR |

5× p/w, 4 w NR Conventional PT focused on gait training + UC Conventional PT focused on gait training = 30 min + conventional PT = 20 min Hospital Physiotherapist NR NR NR |

||

Lennon (2008)RCT

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

2× p/w, 8 w 50%–60% maximum HR, cycle speed and resistance progressed. Cardiac Rehabilitation programme: Cycle ergometry (UL or LL) + 2 life skills classes + UC Cycle ergometry = 30 min Outpatient rehabilitation Physiotherapist Attendance record NR NR |

NR NR UC NR Outpatient rehabilitation Physiotherapist + Occupational Therapist Attendance record NR NR |

||

Leroux (2005)Cohort study

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

2× p/w, 8w RPE: Borg 4–6 “somewhat strong” to “strong” Functional exercise aimed at strengthening hemiparetic side (UL and LL), improving balance, mobility and coordination. 60 min Community centre, group format Clinical Exercise Physiologist Attendance recordVerbal feedback to correct posture and movement NR |

N/A | ||

Mayr (2007) Randomised cross‐over trial

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

5× p/w, 9 w (divided into blocks of 3w) NR. BWS initially 40%, gradually reduced to 0%, walking duration gradually increased to 30 min, speed initially 0.28 m/s, gradually increased, guidance force initially 100%, gradually reduced to 15%. A = Lokomata training B = UC. Order: ABA A ≤ 45 (net 30 min), B = 45 min (net 30 min) Inpatient rehabilitation Therapist Attendance record Visual feedback about speed, time, distance NR |

5× p/w, 9w (divided into blocks of 3w) NR A = Lokomat training B = UC. Order: BAB A ≤ 30 min net time, B = 30 min net time Inpatient rehabilitation Therapist Attendance record NR NR |

||

Mehrholz (2006) Case series

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

5× p/w, 6w NR Modified jump training + UC Jump = 5 to 7 min (replacing 10% of therapy session). Three different jumps, each 30 s. UC = NR Inpatient rehabilitation Physiotherapist NR Assistance to motivate participant NR |

N/A | ||

Morone (2011) RCT with 4 arms

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

5× p/w, 4w NR. Initial BWS: 0%–50%, gradually decreased. Initial speed: 1.0 to 1.5 km/hr, gradually increased. BWS Gait Trainer IIc + PT Robotic gait = 40 min (net time 20 min), PT = 140 min Rehabilitation unit Physiotherapist Attendance record Verbal feedback to encourage correct posture NR |

5× p/w, 4w NR Over ground walking training + PT Gait training = 40 min, PT = 140 min Rehabilitation unit Physiotherapist Attendance record NR NR |

||

Ng (2008) RCT with 3 arms

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

5× p/w, 4w NR. BWS initially 20%, reduced gradually. Speed 0.17 m/s, increased gradually Int. 1: BWS Gait Trainer (GT II)c + PT + UC Gait = 20 min, PT = 40 min, UC = 90 min Hospital Physiotherapist Attendance record Verbal cueing for correct posture NR |

5× p/w, 4w NR. BWS initially 20%, reduced gradually. Speed 0.17 m/s, increased gradually Int. 2: BWS Gait Trainer II with FES + PT + UC Gait = 20 min,PT = 40 min, UC = 90 min Hospital Physiotherapist Attendance record Verbal cueing for correct posture NR |

5× p/w, 4w NR Conventional overground gait training + PT + UC Gait = 20 min, PT = 40 min, UC = 90 min Hospital Physiotherapist Attendance record NR NR |

|

Ochi (2015) RCT

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

5× p/w, 4w NR. Initial speed 0.21 m/s. Gait Assistance Robot (no BWS)d + PT+ UC (OT, SLT) Gait = 20 min, PT = 60 min + UC<120 min Hospital Therapist NR Visual biofeedback to encourage higher work load NR |

5× p/w, 4w NR Overground walking training + Robot assisted UL training + PT+ UC (OT, SLT) Gait = 20 min, robot‐assisted UL training = 20 min, PT = 60 min+ UC <120 min Hospital Therapist NR NR NR |

||

Plummer (2007) Cohort study

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

3× p/w (total of 36 sessions, no more than 16w) Borg 12–13, HR<70% max. predicted. Initial BWS 40%, gradually reduced. Time of continuous treadmill walking progressed. Speed gradually increased. BWSTT + overground walking + UC BWSTT = 20 to 30 min, overground walking = 10 to 15 min, UC = NR NR Physiotherapist Attendance record NR Yes but no information on content, dose. |

N/A | ||

Potempa (1995) RCT

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

3× p/w, 10w Initially 30% to 50% max workload, increased during first 4w. to highest effort rate, maintained over remaining 6w Adapted cycle ergometry 30 min Laboratory NR NR NR NR |

3× p/w, 10w NR Passive ROM 30 min Laboratory NR NR NR NR |

||

Richards (1993) RCT with 3 arms

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

2× p/d, 5w Experimental: “Early Intensive” Early gait re‐education; treadmill, tilt table + UC Started asap post inclusion. Average 1.74 ± 0.15 hr p/d Inpatient hospital Physiotherapist Number of sessions and duration recorded NR NR |

2× p/d, 5w Control 1: “Intensive” Early conventional PT+ UC Average 1.79 ± 0.10 hr p/d Inpatient hospital Physiotherapist Number of sessions and duration recorded NR NR |

1× p/d, 5w Control 2: “Not intensive” Conventional PT+ UC Average 0.72 ± 0.10 hr p/d Inpatient hospital Physiotherapist Number of sessions and duration recorded NR NR |

|

Rosendahl (2006) RCT with 4 arms

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

5× every 2w, 3 months (total 29 sessions) “High”. Strength at 8–12 RM Int. 1: High Intensity Functional Exercise + Protein drink 45 min Care home Physiotherapist Attendance record Verbal encouragement to work at high intensity NR |

5× every 2w, 3 months (total 29 sessions) “High”. Strength at 8–12RM Int. 2: High Intensity Functional Exercise + Placebo drink 45 min Care home Physiotherapist Attendance record Verbal encouragement to work at high intensity NR |

5× every 2w, 3 months (total 29 sessions) NR Cont. 1: Sitting activities + Protein drink 45 min Care home Occupational Therapist Attendance record NR NR |

5× every 2w, 3 months (total 29 sessions) NR Cont. 2: Sitting activities + Placebo drink 45 min Care home Occupational Therapist Attendance record NR NR |

| Shea (2014) Case study | Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

1 to 2× p/w, 9 months, 58 sessions NR Classical Pilates with adaptations in lying/ sitting 55 min Initially home, progressed to Pilates studio Certified Pilates teacher Attendance record Verbal cues as required NR |

N/A | ||

Stoller (2015) RCT

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

3× p/w, 4w (12 sessions) RPE 6–20. Initial work rate 40% of peak work rate, increased by 5% per session. Target HR 40%–70% HR reserve. Cadence 60 steps/min BWS individually adjusted. BWS Lokomata with real‐time feedback control + UC BWSTT = 30 min, UC = 60–120 min NR Physiotherapist Attendance record NR NR |

3× p/w, 4w (12 sessions) RPE 6–20. Cadence 60 steps/min BWS individually adjusted. BWS Lokomat + UC BWSTT = 30 min, UC = 60–120 min NR Physiotherapist Attendance record NR NR |

||

Teixeira da Cunha Filho (2001, 2002) RCT

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

5× p/w until discharged (minimum 9 sessions) NR. Initial BWS 30%, gradually reduced, speed increased BWSTT + UC BWSTT = 20 min, UC = 3 hr (i.e., 1 hr PT, 1 hr OT, 1 hr kinesiotherapy) Hospital Physiotherapist Attendance record NR NR |

5× p/w until discharged (minimum 9 sessions) NR Overground Gait training + UC Overground Gait training = 20 min, UC = 3 hr (i.e., 1 hr PT, 1 hr OT, 1 hr kinesiotherapy) Hospital Physiotherapist Attendance record NR NR |

||

Tong (2006) RCT with 3 arms

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

1× p/w, 4w PT and UC: 5× p/w, 4w NR. Partial body weight support, gradually reduced. Target training speed 0.2–0.6 m/s Int. 1: BWS Gait Trainer IIc + PT + UC Gait = 20 min, PT = 40 min, UC = 90 min Rehabilitation hospital Physiotherapist Attendance record Verbal cues to reduce manual support NR |

1× p/w, 4w PT and UC: 5× p/w, 4w NR. Partial body weight support, gradually reduced. Target training speed 0.2–0.6 m/s Int. 2: BWS Gait Trainer II & FES + PT + UC Gait = 20 min, PT = 40 min, UC = 90 min Rehabilitation hospital Physiotherapist Attendance record Verbal cues to reduce manual support NR |

1× p/w, 4w PT and UC: 5× p/w, 4w NR PT (including overground walking training) + UC Gait = 20 min, PT = 40 min, UC = 90 min Rehabilitation hospital Physiotherapist Attendance record NR NR |

|

Tsaih (2012) RCT

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

3× p/w, 4w NR. Increased as per tolerance Functional walking (e.g., treadmill, stairs, overground walking) 30–45 min Care home Physiotherapist Attendance record Verbal encouragement to increase distance, speed NR |

NR NR UC NR Care home Care/rehab staff at care home Attendance record NR NR |

||

Vidoni (2008) Case study

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

2× p/w, 18w NR. BWS (30%), speed 0.18–0.27 m/min A: Over ground walking (6 w), B: BWSTT (6w), C: Over‐ground walking with motor learning concepts (6w) 60 min (net time 30 min). NR Physiotherapist Attendance record Verbal encouragement NR |

N/A | ||

Wang (2014a)RCT

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

Cycle ergometer: 3× p/w, UC (incl. PT): 5× p/w, 6w Low Cycle ergometer aerobic training + UC (incl. PT) Cycle = 40 min (instead of PT), UC (incl. PT) = 210 min Hospital Therapist Attendance record Verbal encouragement to increase affected leg use NR |

5× p/w, 6w NR UC (incl.PT) 210 min Hospital Therapist NR NR NR |

||

Wang (2014b)RCT

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

Cycle ergometer: 3× p/w, UC (incl. PT): 5× p/w, 6w Low Cycle ergometer aerobic training + UC (incl. PT) Cycle = 40 min (instead of PT), UC (incl. PT) = 210 min Hospital Therapist Attendance record Verbal encouragement to increase affected leg use NR |

5× p/w, 6w NR UC (incl.PT) 210 min Hospital Therapist NR NR NR |

||

White (2013) Mixed methods cohort study + +

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

4× over 9w Borg Scale: Moderate Masterstroke: Mixed training (including treadmill and bike) + Education (stroke risk factors, diet, stroke complications) Mixed training = 60 min, Education = 60 min Hospital, group format Mixed training: Physiotherapist, Education: MDT member community support team NR NR NR |

N/A | ||

Yagura (2006) RCT

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

3× p/w, 6w NR. BWS up to 50%, speed gradually increased (0.2–3.0 km/hr) BWSTT with facilitation + PT + UC BWSTT = 20 min, PT = 20 min Inpatient rehabilitation hospital Physiotherapist NR NR NR |

3× p/w, 6w NR BWSTT with no facilitation + PT+ UC BWSTT = 20 min, PT = 20 min Inpatient rehabilitation hospital Physiotherapist NR NR NR |

||

Yang (2014) Randomised cross‐over

|

Frequency Intensity Type Time Setting Who Adherence Motivation Home Program |

Cycling = 5× p/w, 4w with UC = 5× p/w, 8w “A little strenuous” (Borg 13) C = Cycling + UC, D = UC. Order: CD Cycling = 30 min, UC = 120 min Outpatient rehabilitation in university hospital Physiotherapist NR Visual biofeedback of load symmetry of lower extremities NR |

Cycling = 5× p/w, 4w with UC = 5× p/w, 8w “A little strenuous” (Borg 13) C = Cycling + UC, D = UC. Order : DC Cycling = 30 min, UC = 120 min Outpatient rehabilitation in university hospital Physiotherapist NR NR NR |

||

Adherence: Reporting of adherence to the exercise programme. BWS: Body Weight Support, BWSTT: Body Weight Supported Treadmill Training, ECG: electrocardiogram, Home Programme: details of home exercise programme, HR: Heart Rate, LL: Lower Limb, MDT: Multi‐disciplinary team, Motivation: Details of any motivation strategies, N/A: Not applicable, NDT: Neurodevelopmental Treatment (based on Bobath principles), NR: Not Reported, OT: Occupational Therapist, p/d: per day, p/w: per week, PT: Physiotherapy, RAGT: Robot Assisted Gait Training, Reps.: number of repetitions, RM: repetition maximum, NR: not reported, ROM: Range of Movement, RPE: Rate of Perceived Exertion, SLT: Speech and Language Therapy, UC: Usual Care, UL: Upper Limb, w: weeks, Who: profession of staff delivering the intervention.

Cycle ergometry,

Cycle ergometry,  Gait training.

Gait training.

Devices: aLokomat is a robot‐driven gait orthosis controlling hip and knee movement, combined with BWS and a treadmill. bG‐EO Systems Robot is a robotic device comprising of footplates, the trajectories of which can be programmed, together with a BWS system. cGait Trainer (GTII) is a robotic device that controls the propulsion of footplates with a BWS system. dGait Assistance Robot (GAR) is a robotic device comprising four robotic arms controlling proximal and distal parts of the leg, thigh cuffs, leg apparatuses, a treadmill‐but no BWS.

Table 6.

Overview of the outcomes of non‐ambulatory participants only

| Author (year)Study design | Assessment time points and outcome measures | Results |

|---|---|---|

Batcho (2013)bCohort study

|

Two baseline assessments (data reported from baseline 2), end of intervention and 3 month follow up

|

Median (range)

|

Chang (2012)®RCT

|

Baseline, end of intervention

|

Between group comparisons:

|

Cho (2015)Randomised cross‐over trial

|

Baseline, end of intervention (i.e., 4 w, 8 w)

Primary:

|

Data at point of cross‐over not presented; data from RAGT phases combined for both groups and compared with data from non‐RAGT phase combined for both groups:

|

Dean (2010)RCT

|

Baseline data NR. Outcomes at 6 months after study entry. Walkers only:

|

|

Demers (2015)bMixed Methods

|

Pre, post intervention

|

Pre, post (median (range)):

|

Franceschini (2009)RCT

|

Baseline (T0), after 10 sessions (T1), end of intervention (T2), 2 weeks post intervention (T3) + 6 months post stroke onset (T4)

|

1–13. No significant between‐group difference in any outcome measure at any time. |

Hesse (1994) Cohort study

|

Baseline, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 days after start of intervention. FAC recorded −15, −10, −5 days before start of intervention.

|

Mean change (range) in outcomes 1–5 pre to post intervention:

|

Hesse (1995)Case study

|

Outcome 1–4: Baseline, end of every week, outcome 5: 2× pw.

|

Comparisons between each 3‐week intervention period (A: BWSTT, B: PT, A: BWSTT)

|

Hesse (2010)®Case study within observational study

|

Case study: Baseline, end of intervention

|

Pre‐ post intervention values for single case study:

|

Hesse (2012)Non‐randomised clinical trial

|

Baseline, after 2 w, after 4 w (intervention end), 3 month follow up Primary:

|

Alpha set at 0.025.

|

Husemann (2007)RCT

|

Baseline end of intervention. Primary:

|

|

Lennon (2008)aRCT

|

Baseline, end of intervention

|

Mean difference (95% CI) baseline ‐ end of intervention:

|

Leroux (2005) Cohort study

|

Baseline + end of intervention

|

Alpha set at 0.008

|

Mayr (2007)bRandomised cross‐over trial

|

Baseline and at each point of crossover at 3, 6 weeks + 9 weeks

|

Data for baseline and 1st point of crossover at 3 weeks (Mean ± SD):

|

Mehrholz (2006)Case series

|

Baseline, end of intervention

|

|

Morone (2011)bRCT with 4 arms: Robotic Group (Low Motricity; RGLM), Control Group (Low Motricity, CGLM), Robot Group (High Motricity, RGHM), Control Group (High Motricity, CGHM)

|

Outcome 1: after 4 w intervention and at hospital discharge. Outcomes 2–8: Baseline, 4w intervention and at discharge. Primary:

|

Low Motricity (LM): MI ≤ 29, high motricity (HM): MI > 29. Comparison: RGLM versus CGLM:

|

Ng (2008)RCT with 3 arms

|

Baseline, end of intervention, 6 month follow up

|

Comparison between intervention group 1 (GT) and control group only:

|

Ochi (2015)RCT

|

Baseline, end of intervention

|

|

Plummer (2007)Cohort study

|

Outcome 1. Baseline, sessions 12, 24, 36 (end of training), 2. Baseline, end of training, 3. Baseline, session 18, end of training, 4. Baseline, sessions 12, 24, end of training, 5. Baseline, end of training, 6–9. Baseline, end of training.

|

Results for single non‐ambulatory participant (only baseline and end of intervention data presented here):

|

Potempa (1995)RCT

|

Baseline, end of intervention At rest:

|

|

Richards (1993)RCT with 3 arms

|

Baseline and end of intervention at 6 weeks and 3, 6 months follow‐up

|

Gait training and Conventional Therapy (Cont..2) compared only

|

Rosendahl (2006)bRCT with 4 arms

|

Baseline, 3 months (end of intervention), 6 month follow up

|

Int. 2 and Cont. 2 groups compared only.Difference between 3 months‐baseline; 6 months‐baseline (median, range):

|

| Shea (2014)Case study 7#x00A0; PILATES |

Baseline, 3 months, 6 months , 9 months (end of intervention)

|

Baseline – 9 months : (interim data not presented here):

|

Stoller (2015)RCT

|

Primary: at Baseline, end of intervention:

|

|

Teixeira da Cunha Filho (2001)RCT

|

Baseline + end of intervention at discharge Cycle ergometry:

|

|

Teixeira da Cunha Filho (2002)RCT

|

Gait parameters

|

1–5: No significant between‐group difference in any outcome.

|

Tong (2006)RCT with 3 arms

|

Baseline, mid training (after 2 weeks), end of intervention (after 4 weeks)

|

Baseline‐end of intervention (w4) comparisons between Cont. and Exp. 1 group only (all other data not presented here):

|

Tsaih (2012) bRCT

|

Baseline, end of intervention at w4

|

Mean (SD)

|

Vidoni (2008)Case study

|

Baseline and weekly assessment.

|

Mean (SD) following each type of gait training in single case study: A: Over ground walking, B: BWSTT, C: Over‐ground walking with motor learning:

|

Wang (2014a)RCT

|

Baseline, end of intervention

|

Intention to treat analysis:

|

Wang (2014b)RCT

|

Baseline, end of intervention

|

|

White (2013)b Mixed methods cohort study + +

|

Baseline, end of intervention,3 month follow up

|

Changes between End intervention ‐ baseline, Follow‐up – baseline (Median, range):

|

Yagura (2006)RCT

|

Baseline (admission), 4 w post admission prior to BWSTT starting, 10 w post admission (after 6 w BWSTT), 16 w post admission follow‐up. Gait speed and cadence measured every two weeks up to 16 w.

|

|

Yang (2014)b Randomised cross‐over

|

Baseline, after 4 w (point of cross over), 8 w (end of intervention)

|

Change from baseline – 4 weeks (single participant in each RCT arm). Only change from baseline to cross‐over reported here:

|

1RM: 1 Repetition Maximum, 6 minWT: 6 minute Walk Test, 10mWT: 10 metre Walk Test, ADL: Activities of Daily Living, AS: Ashworth scale, BBS: Berg Balance Scale, BI: Barthel Index, BMI: Body Mass Index, BP: Blood Pressure, bpm: Beats per minute, BWSTT: Body Weight Supported Treadmill Training, CGHM: control group with high motricity, CGLM: control group with low motricity, CI: Confidence Interval, CNS: Canadian Neurological Scale, Cont.: Control, CT/OCGT: Conventional overground gait training, DBP: Diastolic Blood Pressure, EKG: electrocardiogram, EMS: Elderly Mobility Scale, Exp.: experimental, FAC: Functional Ambulation Category, FEV: Forced Expiratory Volume, FIM: Functional Independence Measure, F‐M: Fugl‐Meyer Scale, FES: Functional Electrical Stimulation, GT: Electromechanical gait trainer, HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HDL: High Density Lipoprotein, HOMA‐IR: Homeostatic Model Assessment‐Insulin Resistance, HR: Heart Rate, Int.: Intervention, LDL: Low Density Lipoprotein, LL: Lower Limb, mAS: Modified Ashworth Scale, MBI: modified Barthel Index, MD: Mean difference, Med: median, MFRT: Modified Functional Reach Test, MI: Motricity Index, MRC: Medical Research Council, NR: Not reported, O2: Oxygen, P peak: peak work rate, RAGT: Robot Assisted Gait Training, RCT: Randomised Control Trial, RER: Respiratory Exchange Ratio, RGLM: robot group with low motricity, RGHM: robot group with high motricity, RMI: Rivermead Mobility Index, RM: repetition maximum, RPE: Rate of Perceived Exertion, Rfpeak: peak respiratory rate, SAQOL: Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale, SBP: Systolic Blood pressure, SD: Standard Deviation, SIAS: Stroke Impairment Assessment Set, SIS: Stroke Impact Scale, TCT: Trunk Control Test, TUG: Timed Up and Go Test, VO2: maximum oxygen volume, CCO2: maximum carbon dioxide volume, UL: upper limb, V E: Expiratory Volume, w: weeks.

All data were extracted from publications, except in cases indicated by: aAnalysed data supplied by the author. bData supplied by author, analysed by review authors (ML, FvW).

Table 7.

Overview of dropouts involving non‐ambulatory participants only (intervention period, follow up period—where included) and adverse events

| Author (year) | Group | Drop outa (number of non‐ambulatory stroke participants) during intervention period and follow up period (where included) | Adverse eventsb (number of non‐ambulatory stroke participants experiencing event, and event description as stated by authors) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Possibly intervention related | General health/death | Logistical/refusal | Unknown | Not reported | Total entire study period (%) | |||

| Batcho (2013) | N/A | 0 | 0,0, 1/0 | 0/0, 1/0 | 0, 0 | 0, 0 | 2 (33%) | N = 1 (ankle injury, also reason for dropout) |

| Chang (2012) | Int. | 0 | 1/0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5%) | N = 1 (aspiration pneumonia—also reason for dropout) |

| Cont. | 3 | 3/0 | 0/1 | 0 | 0 | 7 (29%) | N = 1 (low back pain). N = 1 (recurrent stroke) and N = 1 (uncontrolled seizure): also reasons for dropout | |

| Cho (2015) | Int. | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | N = NR, however authors reported a “high dropout rate” including the following reasons: health status aggravation, “adverse dermatological effects”c |

| Cont. | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Dean (2010) | Int. | 2 | 0/2, 0/1 | 0/0, 0/0 | 0, 0 | 0, 0 | 5 (8%) | N = 2 (anxiety due to treadmill training, also intervention related reason for drop out) |

| Cont. | 0 | 0/2, 0/0 | 0/0, 0/0 | 0, 0 | 0, 0 | 2 (3%) | NR | |

| Demers (2015)d | N/A | 0 | 1/0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (20%) | Increased fatigue in all 4 non‐ambulatory participants but this was not a reason to stop |

| Franceschini (2009) | Int. | 2 | 4c/0, 0/1 (Int.. group) | 6c/0, 0/0 | 0, 0 | 0,0 | 10 (19%) | N = 2 (discomfort from harness, also intervention related reason for drop out) |

| Cont. | 0 | 5/0, 0/0 | 3, 0 | 0, 0 | 8 (18%) | |||

| Hesse (1994) | N/A | 0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NR |

| Hesse (1995) | N/A | 0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) | NR |

| Hesse (2010) | N/A | 0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) | None observed |

| Hesse (2012) | Int. | 0 | 0/0, 0/0 | 0/0, 0/0 | 0, 0 | 0, 0 | 0 (0%) | N = 1 (aggravation of knee OA) |

| Cont. | 0 | 0/0, 0/0 | 0/0, 0/1 | 0, 0 | 0, 0 | 1 (7%) | NR | |

| Husemann (2007) | Int. | 0 | 1/0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6%) | N = 2 (skin lesions), N = 1 (ankle distortion , N = 1 (enteritis, also reason for health‐related dropout) |

| Cont. | 0 | 0/1 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6%) | N = 3 (DVT), N = 1 (pulmonary artery embolism, also cause of drop‐out and death) | |

| Lennon (2008)d | Int. | 0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) | N/A |

| Cont. | 0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) | N/A | |

| Leroux (2005) | N/A | 0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) | NR |

| Mayr (2007)d | Int. | 0 | 1/0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (14%)* | N = 1 (Tumour ) |

| Cont. | NR | NR/0 | NR | 0 | 0 | 3 (60%)* | N = NR (Bad general condition, quit study without reason) | |

| Mehrholz (2006) | N/A | 0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) | N = 1 (shoulder pain) |

| Morone (2011) | Int. | Figures NR | Figures NR/0 | Figures NR | 0 | 0 | 12 (50%) | N = 3 (severe, symptomatic hypotension), N = 1 (paretic leg knee pain), N = NR (perceived weakness, uncontrolled blood pressure, fever, urinary tract infection) |

| Cont. | Figures NR | Figures NR/0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 9 (38%) | N = 3 (details NR) | |

| Ng (2008)e | Int. | 0, 0 | 0/0, Figures NR per group | 0/0, Figures NR | 2, Figures NR | 0, 0 | 2 (6%) | None observed during treatment. AE during follow upc: N = 1 (died), N = 3 (recurrent stroke) |

| Cont. | 0, 0 | 2/0, Figures NR per group | 2/0, Figures NR | 3, Figures NR | 0, 0 | 7 (33%) | N = 1 (hospital admission), N = 1 (deteriorating medical condition) | |

| Ochi (2015) | Int. | 0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) | None observed |

| Cont. | 0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) | NR | |

| Plummer (2007) | N/A | 0 | 0/0 | NR | 0 | 0 | NR | None observed |

| Potempa (1995) | Int. | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Cont. | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Richards (1993)e | Int. | NR | NR | NR | 1 | 0 | 1 (10%) | NR |

| Cont. | NR | NR | 0/1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (11%) | NR | |

| Rosendahl (2006)d , e | Int. | 0, 0 | 0/0, 0/3 | 0/0, 0/1 | 0, 0 | 0, 0 | 4 (50%) | 6 AE among 3 participants (3 musculoskeletal, 2 respiration/circulation, 1 psychological) |

| Cont. | 0, 0 | 0/0, 0/0 | 1/0, 0/0 | 0, 0 | 0, 0 | 1 (13%) | 3 AE among 3 participants (2 unknown, 1 psychological) | |

| Shea (2014) | N/A | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) | None observed |

| Stoller (2015)c | 0 | 5/0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 (33%) | None observed during training. AE after recruitment but prior to randomisation: N = 1 (uncontrollable spasticity), N = 1 (skin lesion), N = 1 (severe groin pain), N = 1 (suspected cerebrospinal fluid leak), N = 1 (respiratory infection) (all reasons for dropout) | |

| Teixeira da Cunha Filho (2001, 2002) | Int. | 0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (14%) | N/A |

| Cont. | 0 | 1/0 | 1/0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (25%) | N = 1 (pulmonary complication) | |

| Tong (2006)e | Int. | 0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) | None observed |

| Cont. | 0 | 2/0 | 2/0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (20%) | N = 1 (hospital admission), N = 1 (deteriorating medical condition) | |

| Tsaih (2012)d | Int. | NR | NR /0 | NR/NR | NR | 0 | NR | None Observed. Participants attended all intervention sessions |

| Cont. | NR | NR /0 | NR/NR | NR | 0 | NR | None Observed. Participants attended all intervention sessions | |

| Vidoni (2008) | N/A | 0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) | Chronic back pain, discomfort during BWSTT and respiratory infection |

| Wang (2014a) | Int. | 0 | 0/0 | 3/2 | 0 | 0 | 5 (21%) | N = 2 (hospital admission, incl. N = 1 DVT), N = 3 (discomfort or unpleasant feelings after training) N = NRc (General fatigue, pain and discomfort in affected leg, psychological reasons |

| Cont. | 0 | 5/0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (21%) | ||

| Wang (2014b) | Int. | 2 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 2 | 0 | 4 (15%) | N = 2 (discomfort in affected leg, also intervention related reason for drop out) |

| Cont. | 0 | 3/0 | 0/0 | 2 | 0 | 5 (19%) | N = 4 (pain and discomfort in lower limb)c | |

| White (2013) | N/A | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Yagura (2006) | Int. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4%) | N = 1 (harness discomfort ‐also intervention related reason for drop out) |

| Cont. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4%) | N = 1 (harness discomfort ‐also intervention related reason for drop out) | |

| Yang (2014) | Int. | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) | None observed |

| Cont. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) | None observed | |

AE: adverse event, BWSTT: body weight supported treadmill training, Cont.: Control, DVT: Deep Vein Thrombosis, Int.: Intervention, N: number of participants affected, N/A: Not applicable, NR: Not reported, OA: Osteoarthritis, SAE: Serious Adverse Event.

aDrop out categorisation assessed by review authors, based on description in published article. bAE as described by study authors in publication. cGroup allocation not specified. dData supplied by study authors. eData presented only for group(s) included in this review.

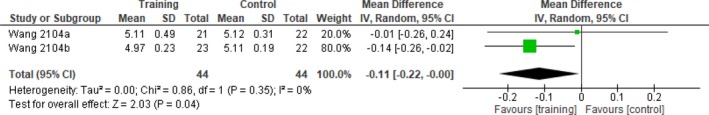

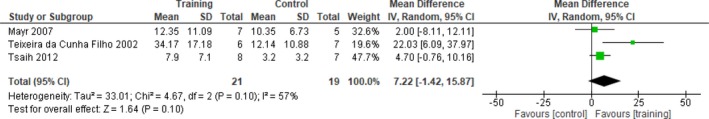

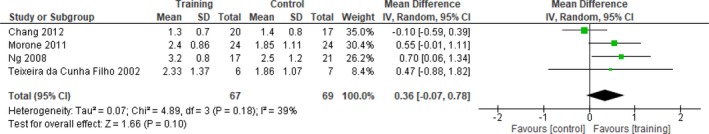

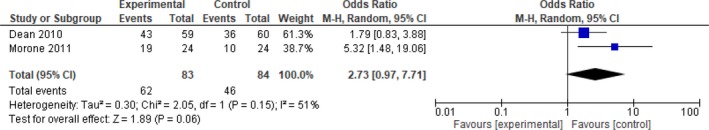

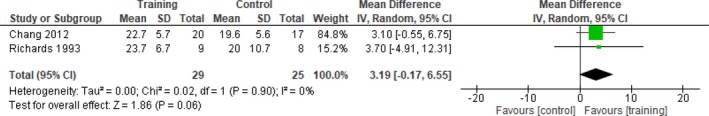

For the analysis of intervention effects, only data from RCTs were used, as this type of design yields the highest quality evidence. Randomized crossover studies were also included—but only up to and including the point of crossover. Data from non‐RCTs were analyzed descriptively only. For a comprehensive overview, data from all included studies are reported in the data tables (Tables 4, 5, 6, 7). For the meta‐analysis, only outcomes used in two or more RCTs were entered; outcomes used in one study only are described in the text and presented in the tables. To synthesize quantitative data from RCTs, RevMan 5.3 software (RevMan 2014) was used for meta‐analysis purposes (Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). Where studies used varying subscales of the same outcome measure (e.g., the full Fugl‐Meyer or its lower limb subscale only), the standardized mean difference (SMD) was used instead of the mean difference (MD). Only data reported as standard deviation were entered in the meta‐analysis; data presented as standard error were converted to standard deviation before being entered. Data reported as medians and (interquartile) ranges, which did not allow their distribution to be examined for skewness, were not included in meta‐analysis (Higgins & Green, 2011). In cases where multiple baseline assessments were reported that were not significantly different, the last baseline measure was used. Final values at the end of intervention and at follow‐up (where included) were used. To establish the odds of regaining independent walking, an odds ratio (OR) was computed. Variability was assessed with the Chi‐square test for statistical heterogeneity and the I 2 statistic for inconsistency across studies, which are both included in the RevMan forest plots. However, as the Chi‐square test has low power in meta‐analyses when the sample size is small or when the number of events is small, the significance level was set at 0.10 rather than at 0.05, and a random‐effects model was used (Higgins & Green, 2011). These processes also ensured comparability with the Cochrane systematic review on physical fitness training after stroke by Saunders et al. (2016).

For the analysis of feasibility, relevant data on adverse events and dropouts from all studies were included. For case fatality, the number of deaths in each group and the total number of participants in each group were entered into the meta‐analysis as dichotomous outcomes and the odds ratios (OR) were computed.

For the analysis of acceptability of interventions, the plan was to use a thematic synthesis of qualitative data. However, no qualitative studies and only two mixed‐methods studies could be included, which had very little qualitative information pertaining to nonambulatory participants, and this is presented narratively.

Following the separate analysis of quantitative and qualitative data, the framework proposed by Thomas et al. (2004) was used to synthesize these data.

3. RESULTS

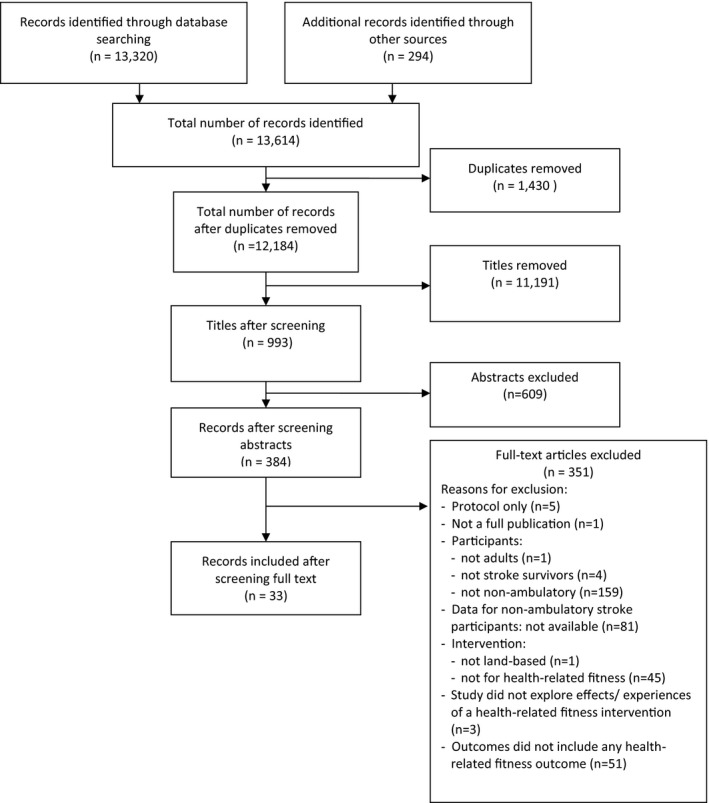

3.1. Study selection