Abstract

Purpose

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths, accounting for over 200,000 annual cases among women. Few studies have investigated the association between breast cancer subtype and survival among African-American women. Here we investigate breast cancer survival among African-American women by breast cancer subtype.

Methods

We analyzed cancer-related deaths among African-American women using data obtained from the SEER database linked to the 2000 U.S. census data. We examined distribution of baseline socio-demographic and clinical characteristics by breast cancer subtypes and used Cox proportional hazard models to determine associations between breast cancer subtypes and cancer-related mortality, adjusting for age, socio-economic status, stage at diagnosis, and treatment.

Results

Among 19,836 female breast cancer cases, 54.4% were diagnosed with the HER2-/HR+ subtype, with the majority of those cases occurring among women ages 55 and older. However, after adjusting for age, stage and treatment type (surgery, radiation, or no radiation and/or cancer directed surgery), TNBC (HR: 2.34; 95% CI: 1.95 – 2.81) and HER2+/HR- (HR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.08 -1.79) cases had significantly higher hazards of cancer related deaths compared with HER2+/HR+ cases. Adjusting for socio-economic status did not significantly alter these associations.

Conclusions

African American women with TNBC were more likely to have a cancer-related death than African American women with other breast cancer subtypes. This association remained after adjustments for age, stage, treatment, and socio-economic status. Further studies are needed to identify subtype specific risk and prognostic factors aimed at better informing prevention efforts for all women.

Keywords: Breast Cancer, Hormone-Receptor Subtype, Triple Negative, African-Americans, Survival

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer accounts for over 200,000 cases annually and is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women in the US[1]. Research suggests that there are racial differences in cancer outcomes as African-American women experience the highest mortality rate and lowest survival for breast cancer when compared to women of other races[1-7]. Multiple studies have indicated that socioeconomic status, comorbidities, prognoses, advanced stage at time of presentation, and healthcare disparities are underlying component causes for the observed racial disparities in breast cancer mortality [5-13].

Breast cancer can be classified according to hormone-receptor status into: HER2+/HR+, HER2-/HR+, HER2+/HR- and TNBC (triple-negative breast cancer, HER2-/HR-) subtypes, based on tumor estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal receptor factor 2 status. Of these, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) has one of the poorest prognoses and highest risk of mortality compared with other subtypes [14,15]. Importantly, African-American women are more likely to be diagnosed with TNBC compared with Whites[16-18,14,6,19,15]. Few studies have investigated the association between breast cancer subtypes and survival among African-American women[15,17,20-24,16]. A recent study by Tao et al. using data from the California Cancer Registry (CCR) reported that compared to White women, African-American women experienced increased hazard for breast cancer related deaths among those diagnosed with stage II and III HR+/HER2- subtype, and stage III triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [20]. In addition, among patients with non-TNBC subtypes, African American women still experience lower survival compared to White women [25]. Since highly effective treatment exists for certain breast cancer subtypes, understanding survival differences by subtype may help identify groups of women in whom targeted efforts are needed to improve treatment and survival.

The purpose of this study was to examine whether there are differences in breast cancer survival among African-American women by breast cancer subtypes, using Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data from 2010 through 2012. We hypothesized that breast cancer survival among African American women would be lower in women diagnosed with TNBC compared to other breast cancer subtypes.

METHODS

Data Source

Our analyses used data obtained from the National Cancer Institute SEER database linked to the 2000 U.S. census data. The study sample included all African-American women diagnosed with breast cancer between 2010 through 2012 in the SEER database. The SEER 18 population-based dataset includes all breast cancer cases diagnosed in the following SEER cancer registries: Atlanta, Connecticut, Detroit, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, San-Francisco-Oakland, Seattle-Puget Sound, Utah, Los Angeles, San Jose-Monterey, rural Georgia, Greater California, Kentucky and New Jersey. SEER covers about 28% of the U.S. population, although the regions included tend to be more urban and suburban compared with the general U.S. population.

Study Variables

The primary outcome in this study was cancer-related death, defined as deaths within 12 months following breast cancer diagnosis. The primary exposure of interest in this study was the breast cancer subtype (i.e., HER2+/HR+, HER2-/HR+, HER2+/HR-, triple negative (TNBC), and unknown). The classification of cancer subtypes is based on SEER variables relating to the hormone receptor status of tumors recorded by the SEER program. TNBC is defined as tumors that are estrogen receptor negative, progesterone receptor negative, and human epidermal receptor factor 2 negative. Variable coding details of hormone receptor (HR) and HER2 have been published elsewhere [16] and are available through the SEER website (http://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/databases/ssf/). Individual level variables assessed in this study included age at diagnosis, stage of diagnosis, number of positive lymph nodes, and first course treatment received. Stage of diagnosis was classified (I, II, III, IV) according to the American Joint Commission on Cancer’s Cancer Staging Manual, 7th Edition[19]. As survival is partly influenced by socio-economic status (SES)[8], we included socio-economic status at the county level in our models based on percent below poverty line and percent with less than 9th grade high school education. We categorized county-level percent below poverty line and percent less than 12 9th grade education into quartiles based on the distribution of all cancer patients.

Ethics Statement

This study was considered exempt by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, as the SEER database is a publicly available and non-identifiable secondary data source.

Statistical Analysis

We examined differences in the distribution of breast cancer subtypes by individual characteristics using Chi-square tests and ANOVA. To estimate the relative mortality rates with 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) by breast cancer subtype, we fit a series of Cox proportional hazards models with cancer-related death as the endpoint. We adjusted the estimates for age, stage at diagnoses, first course treatment received, county-level percent below poverty line and percent with less than 9th grade education. Women were censored for deaths other than breast cancer, or any deaths at the end of 2010. We used Statistical Analysis System version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and STATA/IC 13.1 (STATACorp LP, College Station, TX) for all analyses.

RESULTS

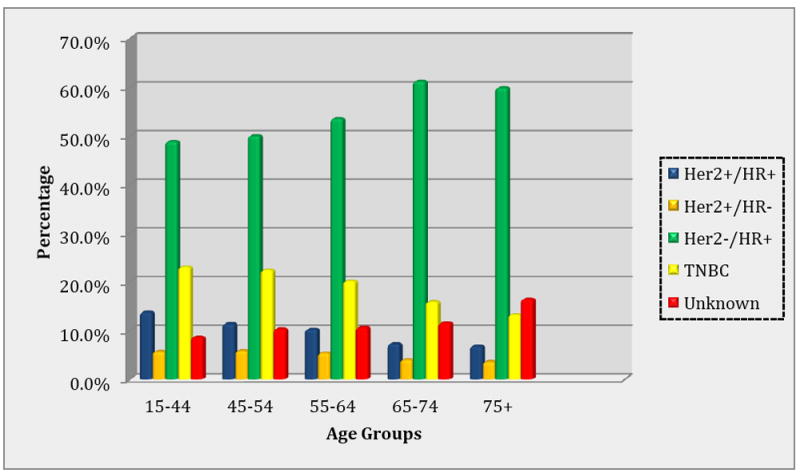

Baseline characteristics of the study population are described in Table 1. Among 19,836 African-American female breast cancer cases included in this analysis, the majority of cases were diagnosed between ages 55-64. More than half (54.4%) of the breast cancer cases were diagnosed with the HER2-/HR+ subtype, and the majority of these cases occurred among women ages 55 and older. However, cases diagnosed with the HER2+/HR+ subtype were significantly younger (19.6% aged 15-44) compared with cases with other breast cancer subtypes (p<0.001). As shown in Figure 1, the proportion of HER2-/HR+ and cases of unknown subtype diagnosed increased with increasing age, while the proportion of other subtypes diagnosed declined with increasing age. Overall, 22.7% of all cases were diagnosed at advanced stages III and IV; however 33.2% of HER2+/HR- cases were diagnosed at advanced stages compared with 27.3% of HER2+/HR+, 25.3% of TNBC cases, and 19.9% of HER2-/HR+ cases.

Table 1.

Comparison of participants’ characteristics by breast cancer subtype, SEER 2010 - 2012.

| Breast Cancer Subtype n (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Cases (N= 19,836) | TNBC N = 3,828 (19.3) | Her2+/HR+ N = 1,976 (10.0) | Her2+/HR- N = 993 (5.0) | Her2-/HR+ N = 10,799 (54.4) | Unknown N = 2,240 (11.3) | p-value | |

| Length of follow-up, months** | 15.5 (10.2) | 15.5 (10.1) | 15.7 (10.3) | 15.7 (10.2) | 15.7 (10.2) | 14.5 (10.6) | <0.001 |

| Age at diagnosis (%) | |||||||

| 15-44 | 2,815 (14.2) | 649 (17.0) | 388 (19.6) | 160 (16.1) | 1,375 (12.7) | 243 (10.9) | <0.001 |

| 45-54 | 4,831 (24.4) | 1,083 (28.3) | 551 (27.9) | 282 (28.4) | 2,416 (22.4) | 499 (22.3) | |

| 55-64 | 5,452 (27.5) | 1,099 (28.7) | 559 (28.3) | 293 (29.5) | 2,920 (27.0) | 581 (25.9) | |

| 65-74 | 3,896 (19.6) | 620 (16.2) | 284 (14.4) | 156 (15.7) | 2,386 (22.1) | 450 (20.1) | |

| 75+ | 2,842 (14.3) | 377 (9.9) | 194 (9.8) | 102 (10.3) | 1,702 (15.8) | 467 (20.9) | |

| % Below poverty line* (%) | |||||||

| 1st Quartile (3.98 – 12.99) | 5,267 (26.6) | 1,005 (26.3) | 517 (26.2) | 261 (26.3) | 2,971 (27.5) | 513 (22.9) | <0.001 |

| 2nd Quartile (13.00 – 17.70) | 4,654 (23.5) | 848 (22.2) | 446 (22.6) | 226 (22.8) | 2,530 (23.4) | 604 (27.0) | |

| 3rd Quartile (17.71 – 20.17) | 4,956 (25.0) | 933 (24.4) | 501 (25.4) | 247 (24.9) | 2,706 (25.1) | 569 (25.4) | |

| 4th Quartile (20.18 – 47.98) | 4,958 (25.0) | 1,042 (27.2) | 511 (25.9) | 259 (26.1) | 2,592 (24.0) | 554 (24.7) | |

| % <9th High School Education* (%) | |||||||

| 1st Quartile (1.08 – 4.43) | 5,002 (25.2) | 991 (25.9) | 500 (25.3) | 278 (28.0) | 2,736 (25.3) | 497 (22.2) | <0.001 |

| 2nd Quartile (4.44 – 5.42) | 5,146 (25.9) | 1,036 (27.1) | 530 (26.8) | 279 (28.1) | 2,806 (26.0) | 495 (22.1) | |

| 3rd Quartile (5.43 – 7.96) | 4,749 (23.9) | 865 (22.6) | 456 (23.1) | 219 (22.1) | 2,623 (24.3) | 586 (26.2) | |

| 4th Quartile (7.97 – 20.88) | 4,938 (24.9) | 936 (24.5) | 489 (24.8) | 217 (21.9) | 2,634 (24.4) | 662 (29.6) | |

| AJCC Stage at Diagnosis (%) | |||||||

| I | 7,566 (38.1) | 1,143 (29.9) | 666 (33.7) | 279 (28.1) | 4,777 (44.2) | 701 (31.3) | <0.001 |

| II | 6,815 (34.4) | 1,615 (42.2) | 710 (35.9) | 361 (36.4) | 3,608 (33.4) | 521 (23.3) | |

| III | 2,851 (14.4) | 669 (17.5) | 320 (16.2) | 206 (20.8) | 1,444 (13.4) | 212 (9.5) | |

| IV | 1,654 (8.3) | 300 (7.8) | 219 (11.1) | 123 (12.4) | 705 (6.5) | 307 (13.7) | |

| Unknown | 950 (4.8) | 101 (2.6) | 61 (3.1) | 24 (2.4) | 265 (2.5) | 499 (22.3) | |

| First course treatment received (%) | |||||||

| Surgery | 7,950 (40.1) | 1,568 (41.0) | 779 (39.5) | 4,735 (43.9) | 4,735 (43.9) | 516 (23.0) | <0.001 |

| Radiation | 94 (0.5) | 27 (0.7) | 10 (0.5) | 11 (1.1) | 39 (0.4) | 7 (0.3) | |

| No Radiation and/or Surgery | 11,753 (59.3) | 2,229 (58.2) | 1,181 (59.8) | 628 (63.2) | 6,010 (55.7) | 1,705 (76.1) | |

| Unknown | 32 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) | 4 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 11 (0.1) | 12 (0.5) | |

Estimated at the county-level

Mean (Standard Deviation)

Figure 1.

Prevalence of breast cancer subtypes by age groups, SEER 2010 – 2012

The distribution of cases residing in low SES communities also varied significantly by subtype (p<0.001). Overall, 26.6% of all cases resided in the lowest quartile of communities with adults living below the poverty line; 27.5% of HER2-/HR+ cases, 26.3% each of TNBC and HER2+/HR- cases and 26.2% of HER2+/HR+ cases. Similarly, 24.9% of all cases resided in communities in the highest quartile of adults with less than 9th grade education; 24.5% of TNBC cases, 24.8% of HER2+/HR+ cases, 24.4% of HER2-/HR+ cases and 21.9% of HER2+/HR- cases. The majority (59.3%) of women received no radiation and/or cancer directed surgery as the first course of treatment for breast cancer.

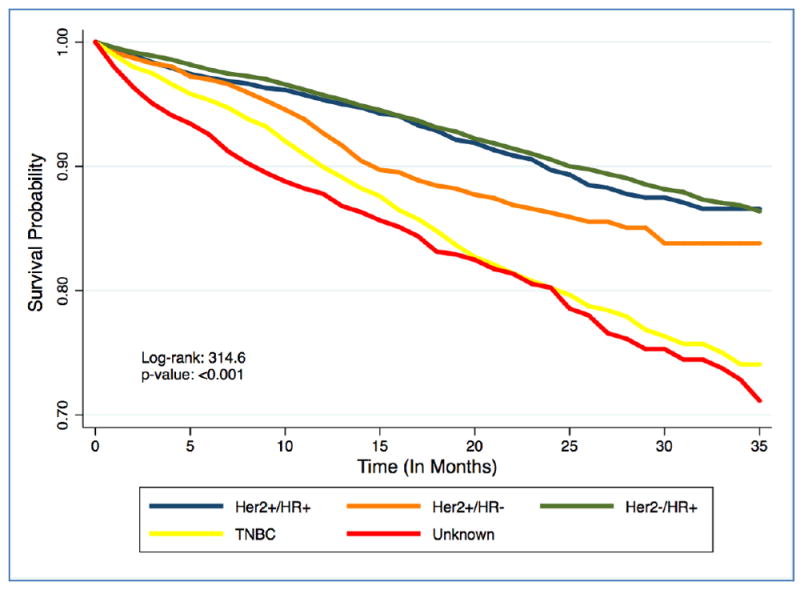

The survival probabilities by subtype are presented in Figure 2, highlighting significant survival differences between the groups (Log-Rank: 314.6; p-value <0.001), and the lowest survival probability observed among cases with TNBC and unknown subtypes. In an unadjusted Cox regression model (Table 2), cases diagnosed with TNBC (HR: 1.97; 95% CI: 1.64 - 2.36) and HER2+/HR- (HR: 1.40; 95% CI: 1.08-1.80) subtypes had significantly higher hazards for cancer-related deaths compared with HER2+/HR+ subtype cases. After adjustment for age, stage and treatment type (surgery, radiation, or no radiation and/or cancer directed surgery) in model 2, the hazards of cancer-related deaths for TNBC (HR: 2.34; 95% CI: 1.95 – 2.81) and HER2+/HR-(HR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.08 -1.79) cases was strengthened and remained statistically significant. In the fully adjusted model additionally adjusting for SES variables, the hazard for cancer-related mortality for TNBC and HER2+/HR- cases were attenuated slightly but remained statically significant.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier Plot for time until death among AA breast cancer cases stratified by breast cancer subtypes, SEER 2010 – 2012

Table 2.

Hazard ratio (HR, 95% CI) of cancer-specific mortality of AA breast cancer cases by subtype, SEER 2010 - 2012.

| No. Deaths (%) Case Fatality | Crude HR* (95% CI) | Model 1 a * (95% CI) | Model 2 b * (95% CI) | Model 3c * (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Subtype | |||||

| Her2+/HR+ (Ref) | 145 (7.3) | - | - | - | - |

| Her2+/HR- | 102 (10.3) | 1.40 (1.08 – 1.80) | 1.38 (1.07 – 1.77) | 1.39 (1.08 – 1.79) | 1.37 (1.06 – 1.77) |

| Her2-/HR+ | 706 (6.5) | 0.89 (0.74 – 1.06) | 0.79 (0.66 – 0.95) | 1.01 (0.85 – 1.21) | 1.02 (0.85 – 1.21) |

| TNBC | 546 (14.3) | 1.97 (1.64 – 2.36) | 1.96 (1.63 – 2.35) | 2.34 (1.95 – 2.81) | 2.33 (1.94 – 2.80) |

| Unknown | 502 (22.4) | 2.89 (2.40 – 3.49) | 2.55 (2.11 – 3.08) | 1.42 (1.18 – 1.73) | 1.43 (1.18 – 1.73) |

| p-value for breast cancer subtype | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Adjusted for age only.

Adjusted for age, stage and treatment.

Adjusted for age, stage, treatment, % below poverty line, and % <9th grade education.

Estimated from Cox proportional hazard model.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the largest study examining cancer-specific survival by hormone receptor subtype among African-American women diagnosed with breast cancer in the US. We observed that cancer related mortality among African-American women diagnosed with TNBC and HER2+/HR- subtypes were significantly higher compared with women diagnosed with other breast cancer subtypes. Even after adjustment for age, stage of disease, treatment and SES, TNBC and HER2+/HR- tumors were associated with a higher hazard for cancer-related death. The most common breast cancer subtype, yet least fatal, among African American women was HER2-/HR+, corresponding to more than half of all breast cancer cases and a case fatality of 6.5%.

To date, few studies have investigated the survival probability associated with breast cancer subtypes among African American women. A recent study reported that among women with stage III TNBC, the hazard for cancer related-death was higher in African American women compared to White women [20]. Additionally, Bauer et al. found that African-American women with late-stage TNBC had the poorest survival, with a corresponding 5-year relative survival of 14% [21]. Both of these previous studies were conducted using the California cancer registry data, and our study adds to this growing body of literature by showing that among African-American women represented in the SEER registry, breast cancer subtype is an important predictor of survival.

Extensive studies have shown that SES plays a critical role in breast cancer survival among African American women [5,7-13], especially when compared with Whites [5,8,11]. This association is likely driven by differences in accessibility and affordability of high quality cancer care. As shown in our analysis, more than half of all cases did not receive radiation or surgery as the first course of treatment, even though almost 35% of cases were diagnosed at stages III and IV. This may be due to a combination of individual, provider and health system factors that influence the ability of African American women to obtain timely and guideline-adherent treatment. For instance, prior studies have shown that African American women are more likely to experience delays in treatment initiation for cancer, and when treated often receive lower quality treatment[9,26-33]. However, our findings suggests that hormone receptor subtype may play a more important role than SES in predicting survival among African American women. Adjusting for SES in our regression models did not appreciably alter the hazard ratio associated with subtype, signifying that improving survival rates among African-American breast cancer patients will require renewed focus on identifying subtype specific etiological factors, and ensuring adequate access to high quality, subtype specific treatment.

Although TNBC was associated with the lowest survival, HER2+/HR- cases also experienced significantly lower survival compared with HER2+/HR+ cases, although this subtype was less prevalent (<1%). On the other hand, TNBC accounted for close to 20% of the cases in our study, consistent with other studies reporting that the lifetime risk of TNBC was nearly doubled in African American women (1.98%, 95%CI: 1.80 – 2.17%) compared to all other races; Asian (0.77%; 95%CI: 0.67 - 0.88%), Hispanic (1.04%, 95%CI: 0.96 – 1.13%), and white women (1.25%; 95% CI: 1.20 – 1.30%)[22]. The risk differential in incidence of HR- subtypes, and the consistent association between hormone receptor negative subtypes and survival reported in several other studies [18,22,34-45], suggest that concerted efforts are needed to identify risk factors associated with HR- tumors, including biological and genetic contributors with a focus on primary prevention. For instance, a previous study showed that metabolic syndrome, a cluster of biochemical abnormalities more prevalent among African-American women compared with Whites, is associated with an almost 2.5-fold increase in the odds of TNBC [46]. In addition, further studies are needed to identify biomarkers of breast cancer risk by subtype, for instance, mammographic density, to further improve screening modalities and early detection. Furthermore, as has been discussed extensively, lack of access to timely and high-quality cancer care remains a significant issue for African-American women regardless of subtype. However few efficacious treatment strategies currently exist for HR- tumors relative to other subtypes[18,37,40,44,45,47-56], making this is a critical area of future research.

This analysis is strengthened by the use of the large, high-quality, standardized data available in the SEER dataset. However, these results should be viewed in light of certain limitations. First, there may be limited generalizability because SEER covers only about 26 percent of the total U.S. population. However, SEER covers geographically and demographically diverse US populations including residents from both rural and urban communities. Thus, in contrast to prior studies using single state registries or smaller study cohorts, this study has modest external validity. Secondly, minority racial/ethnic groups, foreign-born, and urban populations are groups of special interest to the SEER program and are therefore somewhat overrepresented in the database. Lastly, there is a possibility for misclassification bias because measures of SES (i.e., poverty and education) were obtained at times different than cancer diagnosis [8], and may underestimate individual level SES. However, these are the variables currently available in the SEER dataset, and the SES measures were obtained through standardized national surveys.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, in the national SEER cohort, African American women with TNBC were more likely than African American women with other breast cancer subtypes to have a cancer- related death. This association remained after adjustment for age, stage, treatment, and SES. Further efforts should focus on illuminating underlying reasons outside of socio-economic factors that contribute to the higher prevalence and fatality of TNBC.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: NA

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.DeSantis C, Ma J, Bryan L, Jemal A. Breast cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):52–62. doi: 10.3322/caac.21203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlander N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M. Seer Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smigal C, Jemal A, Ward E, Cokkinides V, Smith R, Howe HL, Thun M. Trends in breast cancer by race and ethnicity: update 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56(3):168–183. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.3.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weir HK, Thun MJ, Hankey BF, Ries LA, Howe HL, Wingo PA, Jemal A, Ward E, Anderson RN, Edwards BK. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2000, featuring the uses of surveillance data for cancer prevention and control. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(17):1276–1299. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keegan TH, Kurian AW, Gali K, Tao L, Lichtensztajn DY, Hershman DL, Habel LA, Caan BJ, Gomez SL. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic differences in short-term breast cancer survival among women in an integrated health system. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(5):938–946. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newman LA. Breast cancer disparities: high-risk breast cancer and African ancestry. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2014;23(3):579–592. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tammemagi CM, Nerenz D, Neslund-Dudas C, Feldkamp C, Nathanson D. Comorbidity and survival disparities among black and white patients with breast cancer. JAMA. 2005;294(14):1765–1772. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.14.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akinyemiju TF, Soliman AS, Johnson NJ, Altekruse SF, Welch K, Banerjee M, Schwartz K, Merajver S. Individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status and healthcare resources in relation to black-white breast cancer survival disparities. J Cancer Epidemiol 2013. 2013;490472 doi: 10.1155/2013/490472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akinyemiju TF, Soliman AS, Copeland G, Banerjee M, Schwartz K, Merajver SD. Trends in breast cancer stage and mortality in Michigan (1992-2009) by race, socioeconomic status, and area healthcare resources. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joslyn SA, Foote ML, Nasseri K, Coughlin SS, Howe HL. Racial and ethnic disparities in breast cancer rates by age: NAACCR Breast Cancer Project. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;92(2):97–105. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-2112-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robbins HA, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Shiels MS. Age at cancer diagnosis for blacks compared with whites in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(3) doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sail K, Franzini L, Lairson D, Du X. Differences in treatment and survival among African-American and Caucasian women with early stage operable breast cancer. Ethn Health. 2012;17(3):309–323. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2011.628011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu XQ. Socioeconomic disparities in breast cancer survival: relation to stage at diagnosis, treatment and race. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:364. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parise CA, Caggiano V. Breast Cancer Survival Defined by the ER/PR/HER2 Subtypes and a Surrogate Classification according to Tumor Grade and Immunohistochemical Biomarkers. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;2014:469251. doi: 10.1155/2014/469251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ihemelandu CU, Leffall LD, Jr, Dewitty RL, Naab TJ, Mezghebe HM, Makambi KH, Adams-Campbell L, Frederick WA. Molecular breast cancer subtypes in premenopausal and postmenopausal African-American women: age-specific prevalence and survival. J Surg Res. 2007;143(1):109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.03.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howlader N, Altekruse SF, Li CI, Chen VW, Clarke CA, Ries LA, Cronin KA. US incidence of breast cancer subtypes defined by joint hormone receptor and HER2 status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(5) doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ihemelandu CU, Naab TJ, Mezghebe HM, Makambi KH, Siram SM, Leffall LD, Jr, Dewitty RL, Jr, Frederick WA. Basal cell-like (triple-negative) breast cancer, a predictor of distant metastasis in African American women. Am J Surg. 2008;195(2):153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyle P. Triple-negative breast cancer: epidemiological considerations and recommendations. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 6):vi7–12. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7. Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tao L, Gomez SL, Keegan TH, Kurian AW, Clarke CA. Breast Cancer Mortality in African-American and Non-Hispanic White Women by Molecular Subtype and Stage at Diagnosis: A Population-Based Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(7):1039–1045. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bauer KR, Brown M, Cress RD, Parise CA, Caggiano V. Descriptive analysis of estrogen receptor (ER)-negative, progesterone receptor (PR)-negative, and HER2-negative invasive breast cancer, the so-called triple-negative phenotype: a population-based study from the California cancer Registry. Cancer. 2007;109(9):1721–1728. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurian AW, Fish K, Shema SJ, Clarke CA. Lifetime risks of specific breast cancer subtypes among women in four racial/ethnic groups. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(6):R99. doi: 10.1186/bcr2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma H, Lu Y, Malone KE, Marchbanks PA, Deapen DM, Spirtas R, Burkman RT, Strom BL, McDonald JA, Folger SG, Simon MS, Sullivan-Halley J, Press MF, Bernstein L. Mortality risk of black women and white women with invasive breast cancer by hormone receptors, HER2, and p53 status. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:225. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroenke CH, Sweeney C, Kwan ML, Quesenberry CP, Weltzien EK, Habel LA, Castillo A, Bernard PS, Factor RE, Kushi LH, Caan BJ. Race and breast cancer survival by intrinsic subtype based on PAM50 gene expression. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;144(3):689–699. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2899-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warner ET, Tamimi RM, Hughes ME, Ottesen RA, Wong YN, Edge SB, Theriault RL, Blayney DW, Niland JC, Winer EP, Weeks JC, Partridge AH. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Breast Cancer Survival: Mediating Effect of Tumor Characteristics and Sociodemographic and Treatment Factors. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(20):2254–2261. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. Race, socioeconomic status, and breast cancer treatment and survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(7):490–496. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.7.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cross CK, Harris J, Recht A. Race, socioeconomic status, and breast carcinoma in the U.S: what have we learned from clinical studies. Cancer. 2002;95(9):1988–1999. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dai D. Black residential segregation, disparities in spatial access to health care facilities, and late-stage breast cancer diagnosis in metropolitan Detroit. Health Place. 2010;16(5):1038–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Tamer MB, Homel P, Wait RB. Is race a poor prognostic factor in breast cancer? J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189(1):41–45. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(99)00055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gwyn K, Bondy ML, Cohen DS, Lund MJ, Liff JM, Flagg EW, Brinton LA, Eley JW, Coates RJ. Racial differences in diagnosis, treatment, and clinical delays in a population-based study of patients with newly diagnosed breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100(8):1595–1604. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heimann R, Ferguson D, Powers C, Suri D, Weichselbaum RR, Hellman S. Race and clinical outcome in breast cancer in a series with long-term follow-up evaluation. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(6):2329–2337. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim SH, Ferrante J, Won BR, Hameed M. Barriers to adequate follow-up during adjuvant therapy may be important factors in the worse outcome for Black women after breast cancer treatment. World J Surg Oncol. 2008;6:26. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-6-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li CI, Malone KE, Daling JR. Differences in breast cancer stage, treatment, and survival by race and ethnicity. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(1):49–56. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nielsen TO, Hsu FD, Jensen K, Cheang M, Karaca G, Hu Z, Hernandez-Boussard T, Livasy C, Cowan D, Dressler L, Akslen LA, Ragaz J, Gown AM, Gilks CB, van de Rijn M, Perou CM. Immunohistochemical and clinical characterization of the basal-like subtype of invasive breast carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(16):5367–5374. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vona-Davis L, Rose DP, Hazard H, Howard-McNatt M, Adkins F, Partin J, Hobbs G. Triple-negative breast cancer and obesity in a rural Appalachian population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(12):3319–3324. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K, Karaca G, Troester MA, Tse CK, Edmiston S, Deming SL, Geradts J, Cheang MC, Nielsen TO, Moorman PG, Earp HS, Millikan RC. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA. 2006;295(21):2492–2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rakha EA, El-Rehim DA, Paish C, Green AR, Lee AH, Robertson JF, Blamey RW, Macmillan D, Ellis IO. Basal phenotype identifies a poor prognostic subgroup of breast cancer of clinical importance. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(18):3149–3156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H, Hastie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Thorsen T, Quist H, Matese JC, Brown PO, Botstein D, Lonning PE, Borresen-Dale AL. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(19):10869–10874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown M, Tsodikov A, Bauer KR, Parise CA, Caggiano V. The role of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 in the survival of women with estrogen and progesterone receptor-negative, invasive breast cancer: the California Cancer Registry, 1999-2004. Cancer. 2008;112(4):737–747. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carey LA, Dees EC, Sawyer L, Gatti L, Moore DT, Collichio F, Ollila DW, Sartor CI, Graham ML, Perou CM. The triple negative paradox: primary tumor chemosensitivity of breast cancer subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(8):2329–2334. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, Fluge O, Pergamenschikov A, Williams C, Zhu SX, Lonning PE, Borresen-Dale AL, Brown PO, Botstein D. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406(6797):747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheang MC, Voduc D, Bajdik C, Leung S, McKinney S, Chia SK, Perou CM, Nielsen TO. Basal-like breast cancer defined by five biomarkers has superior prognostic value than triple-negative phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(5):1368–1376. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lund MJ, Trivers KF, Porter PL, Coates RJ, Leyland-Jones B, Brawley OW, Flagg EW, O’Regan RM, Gabram SG, Eley JW. Race and triple negative threats to breast cancer survival: a population-based study in Atlanta, GA. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113(2):357–370. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9926-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reis-Filho JS, Tutt AN. Triple negative tumours: a critical review. Histopathology. 2008;52(1):108–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rakha EA, Ellis IO. Triple-negative/basal-like breast cancer: review. Pathology. 2009;41(1):40–47. doi: 10.1080/00313020802563510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maiti B, Kundranda MN, Spiro TP, Daw HA. The association of metabolic syndrome with triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;121(2):479–483. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0591-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arslan C, Dizdar O, Altundag K. Pharmacotherapy of triple-negative breast cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10(13):2081–2093. doi: 10.1517/14656560903117309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, Suman VJ, Geyer CE, Jr, Davidson NE, Tan-Chiu E, Martino S, Paik S, Kaufman PA, Swain SM, Pisansky TM, Fehrenbacher L, Kutteh LA, Vogel VG, Visscher DW, Yothers G, Jenkins RB, Brown AM, Dakhil SR, Mamounas EP, Lingle WL, Klein PM, Ingle JN, Wolmark N. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(16):1673–1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith I, Procter M, Gelber RD, Guillaume S, Feyereislova A, Dowsett M, Goldhirsch A, Untch M, Mariani G, Baselga J, Kaufmann M, Cameron D, Bell R, Bergh J, Coleman R, Wardley A, Harbeck N, Lopez RI, Mallmann P, Gelmon K, Wilcken N, Wist E, Sanchez Rovira P, Piccart-Gebhart MJ team Hs. 2-year follow-up of trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9555):29–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liedtke C, Mazouni C, Hess KR, Andre F, Tordai A, Mejia JA, Symmans WF, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Hennessy B, Green M, Cristofanilli M, Hortobagyi GN, Pusztai L. Response to neoadjuvant therapy and long-term survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1275–1281. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rouzier R, Perou CM, Symmans WF, Ibrahim N, Cristofanilli M, Anderson K, Hess KR, Stec J, Ayers M, Wagner P, Morandi P, Fan C, Rabiul I, Ross JS, Hortobagyi GN, Pusztai L. Breast cancer molecular subtypes respond differently to preoperative chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(16):5678–5685. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanchez-Munoz A, Garcia-Tapiador AM, Martinez-Ortega E, Duenas-Garcia R, Jaen-Morago A, Ortega-Granados AL, Fernandez-Navarro M, de la Torre-Cabrera C, Duenas B, Rueda AI, Morales F, Ramirez-Torosa C, Martin-Salvago MD, Sanchez-Rovira P. Tumour molecular subtyping according to hormone receptors and HER2 status defines different pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced breast cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2008;10(10):646–653. doi: 10.1007/s12094-008-0265-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hayes DF, Thor AD, Dressler LG, Weaver D, Edgerton S, Cowan D, Broadwater G, Goldstein LJ, Martino S, Ingle JN, Henderson IC, Norton L, Winer EP, Hudis CA, Ellis MJ, Berry DA Cancer, Leukemia Group BI. HER2 and response to paclitaxel in node-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(15):1496–1506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berry DA, Cirrincione C, Henderson IC, Citron ML, Budman DR, Goldstein LJ, Martino S, Perez EA, Muss HB, Norton L, Hudis C, Winer EP. Estrogen-receptor status and outcomes of modern chemotherapy for patients with node-positive breast cancer. JAMA. 2006;295(14):1658–1667. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.14.1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bidard FC, Matthieu MC, Chollet P, Raoefils I, Abrial C, Domont J, Spielmann M, Delaloge S, Andre F, Penault-Llorca F. p53 status and efficacy of primary anthracyclines/alkylating agent-based regimen according to breast cancer molecular classes. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(7):1261–1265. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uhm JE, Park YH, Yi SY, Cho EY, Choi YL, Lee SJ, Park MJ, Lee SH, Jun HJ, Ahn JS, Kang WK, Park K, Im YH. Treatment outcomes and clinicopathologic characteristics of triple-negative breast cancer patients who received platinum-containing chemotherapy. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(6):1457–1462. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]