Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was assess acute and early delayed radiation-induced changes in normal-appearing brain tissue perfusion as measured with perfusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and the dependence of these changes on the fractionated radiotherapy (FRT) dose level.

Patients and methods

Seventeen patients with glioma WHO grade III-IV treated with FRT were included in this prospective study, seven were excluded because of inconsistent FRT protocol or missing examinations. Dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI and contrast-enhanced 3D-T1-weighted (3D-T1w) images were acquired prior to and in average (standard deviation): 3.1 (3.3), 34.4 (9.5) and 103.3 (12.9) days after FRT. Pre-FRT 3D-T1w images were segmented into white- and grey matter. Cerebral blood volume (CBV) and cerebral blood flow (CBF) maps were calculated and co-registered patient-wise to pre-FRT 3D-T1w images. Seven radiation dose regions were created for each tissue type: 0–5 Gy, 5–10 Gy, 10–20 Gy, 20–30 Gy, 30–40 Gy, 40–50 Gy and 50–60 Gy. Mean CBV and CBF were calculated in each dose region and normalised (nCBV and nCBF) to the mean CBV and CBF in 0-5 Gy white- and grey matter reference regions, respectively.

Results

Regional and global nCBV and nCBF in white- and grey matter decreased after FRT, followed by a tendency to recover. The response of nCBV and nCBF was dose-dependent in white matter but not in grey matter.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that radiation-induced perfusion changes occur in normal-appearing brain tissue after FRT. This can cause an overestimation of relative tumour perfusion using dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI, and can thus confound tumour treatment evaluation.

Key words: perfusion MRI, radiation-induced changes, normal-appearing brain tissue, malignant gliomas

Introduction

Radiation-induced changes in brain tissue can be divided into acute, early delayed and late effects.1, 2, 3, 4 Several publications suggest that vascular damage is the primary cause of acute and early delayed effects.3, 5 Both acute and early delayed effects are considered reversible, manifesting as dilation and thickening of blood vessels, decrease in vessel density, endothelial cell damage and disruption of the blood-brain-barrier in normal appearing brain tissue.1, 3, 4, 6

Few studies have assessed radiation-induced changes in brain perfusion in normal appearing brain tissue after fractionated radiotherapy (FRT) or stereotactic radiosurgery.5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Contradictory results have been published, however, perfusion techniques and post-processing methods differ extensively between studies. Overall, the published data show a reduction of both cerebral blood volume (CBV) and cerebral blood flow (CBF) after completion of FRT or single fraction stereotactic radiosurgery, with an inverse dose-response relationship.

Perfusion MRI is useful in the diagnostic evaluation of gliomas as well as for longitudinal response assessment and prognostication, with dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC)-MRI being the most widely applied perfusion MRI technique in clinical practice.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 DSC-MRI is also one of several physiological imaging techniques that has the potential to be incorporated into the Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) criteria as proposed by the RANO working group.21, 22 DSC-MRI can assess perfusion parameters like CBV and CBF but has several limitations, leading to both quantification and reproducibility issues.18 These limitations are related to acquisition and post-processing of the data.15, 16, 18, 23, 24, 25, 26 Generally, only relative measurements, i.e. normalised to a reference region in normal appearing brain tissue, are feasible in clinical practice.19, 26 However, this improves the reproducibility of measurements, which is important for longitudinal comparison.16 Reference tissue can be defined in several ways, but most commonly, contralateral normal-appearing white matter (WM) is used.19, 27 We hypothesize that vascular damages in normal appearing brain tissue secondary to radiation exposure can confound DSC-MRI measurements. Since DSC-MRI is an extensively applied perfusion imaging technique in brain tumours it is important to determine if normalisation to reference tissue is affected by radiation exposure. Consequently, the aim of this prospective study was to assess acute and early delayed radiation-induced changes in normal appearing brain tissue measured with DSC-MRI and the dependence of these changes on the radiation dose given.

Patients and methods

Patients

Seventeen patients, 18 years or older, with newly detected glioma WHO grade III-IV proven by histopathology and scheduled for FRT and chemotherapy were included prospectively. This study was done in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethical committee (Regionala etikprövningsnämnden i Uppsala, approval number 2011/248). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. All patients had undergone surgical resection or biopsy. Baseline MRI was performed prior to FRT (pre-FRT) and post-FRT examinations were scheduled consecutively after the completion of FRT (FRTPost-1, FRTPost-2 and FRTPost-3). The FRT was delivered using 6 megavolt photons with intensity-modulated radiation therapy or volumetric arc therapy. Concomitant chemotherapy was administrated daily during FRT with temozolomide followed by adjuvant chemotherapy starting 4 weeks after completed FRT according to Stupp et al.28 In cases of tumour progression or recurrence, a combination of temozolomide, bevacizumab and/or procarbazine, lomustine and vincristine (in combination further known as PCV) was administrated.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were inconsistent or missing MRI examinations and/or deviation from a prescribed total radiation dose of 60 Gray (Gy).

Image acquisition

All MR examinations were performed with a consistent imaging protocol on a 1.5 T scanner (Avanto Fit, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) and included DSC perfusion and contrast-enhanced 3D-T1-weighted (3D-T1w) images.

Imaging parameters

DSC-MRI (2D-EPI, gradient-echo; Repetition time/Echo time/Flip angle = 1340/30/90; 128 × 128 matrix; 1.8×1.8×5 mm3; time resolution = 1.34 s; 18 slices). A bolus of 5 ml gadolinium-based contrast agent (GBCA) (Gadovist, Bayer AG, Berlin, Germany) was administered for a DCE-MRI and was also regarded as a pre-bolus to diminish the effects of contrast agent extravasation15, 18 for the following DSC-MRI. For the actual DSC-MRI, a second standard dose bolus of 5 ml GBCA was administered. The contrast agent was administered using a power-injector at a rate of 2 ml/s for the first injection and 5 ml/s for the second injection.

3D-T1w image (3D-gradient Echo; Repetition time/Echo Time/Inversion time/Flip angle = 1170/4.17/600/15; 256 × 256 matrix: 1×1×1 mm3: 208 slices)

CT imaging for radiotherapy planning was acquired with a Philips, Brilliance Big Bore (Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands) with a voxel size of 0.525 × 0.525 × 2 mm3.

Perfusion analysis

Signal to concentration time curves conversion has been described previously.29, 30 Concentration time curves were visually inspected before analysis. CBV was determined as the ratio of areas under the tissue and arterial concentration time curves. CBF was determined through deconvolution as the initial height of the tissue impulse function.24, 29 Deconvolution was carried out using standard singular value decomposition (sSVD) with Tikhonov regularisation with an iterative threshold.29, 31, 32, 33 A patient-specific arterial input function (AIF) was defined in the middle cerebral artery branches in the hemisphere contralateral to the tumour19 in the pre-FRT examination, the same AIF was then applied to the patient’s following post-FRT examinations. Contrast agent leakage correction was applied according the method described by Boxerman et al., 2006.34 Vessel segmentation was performed using an iterative five-class k-means cluster analysis to exclude large arteries and veins.35 Calculation of DSC data was performed in NordicICE (NordicNeurolabs, Bergen, Norway).

Data post-processing

CBV and CBF maps were co-registered to the pre-FRT 3D-T1w images for each patient and examination using the SPM12 toolbox (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK). Planned radiation dose levels for each region were acquired by rigidly transforming the dose-planning CT (including related radiation dose plans) to the pre-FRT 3D-T1w images using the standard Elastix registration toolbox.36

Grey matter (GM) and WM probability maps were segmented from the 3D-T1w images, for each examination, using the segmentation tool in the SPM12 toolbox. WM and GM maps were defined as partial volume fraction above 70%. Contrast-enhancing tissue, oedema, resection cavity, tumour progression and recurrence, if present, were excluded, reviewed by an experienced neuroradiologist. Registered radiation dose plans were divided as follows: 0–5 Gy, 5–10 Gy, 10–20 Gy, 20–30 Gy, 30–40 Gy, 40–50 Gy and 50–60 Gy, creating a total of seven binary dose regions for each tissue type, (mean volume and standard deviation for each dose region is presented in S1 Table).

Statistical analysis

Mean CBV and CBF were calculated in each dose region and normalised (nCBV and nCBF) to the mean CBV and CBF in 0–5 Gy WM and GM regions, respectively. Super- and subscripts are used to distinguish between tissue type from which measurements were derived (superscript) and reference tissue type used for normalisation (subscript), i.e. and (same for nCBF). For descriptive analysis, average mean, 95% confidence interval (CI) and standard error of mean (SEM) were calculated region-wise, outlined by radiation dose regions (regional nCBV and nCBF), and globally, incorporating all regional values irrespective of received radiation dose (global nCBV and nCBF). A Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed ranks test was used to compare post-FRT data with pre-FRT data under the null hypothesis: there is no change in nCBV and nCBF after FRT. This was performed for regional values and global values and for GM and WM, respectively. Derived P-values are two-sided and presented as exact values, unless lower than 0.001, in this case they are presented as <0.001. P-values lower than 0.05 were considered significant. Relative change was further defined as:

Mean relative change and standard deviation (SD) were calculated and presented as a part of the descriptive analysis. A linear regression model was applied to assess a possible dose-response relationship between relative change and received radiation dose. Graphpad Prism 7 for Mac (Graphpad Software, La Jolla California USA) was used for statistical analysis and graph design.

Results

Patients

Seven patients were excluded due to inconsistent or missing pre-FRT examinations (n = 5) or deviation from the prescribed total dose of 60 Gy (n = 2). Data from 10 patients were analysed (mean age 55.8 years, SD 8.0 years). All had a histopathological diagnosis of glioblastoma (WHO grade IV). All patients analysed were prescribed a total dose of 60 Gy, however, nine patients had received a fraction dose of 2.0 Gy/fraction and one patient 2.2 Gy/fraction. Seven post-FRT examinations were missing, yielding a total of 33 MR-examinations. Pre-FRT examination was performed in average (SD, number of patients) 9.0 (7.4, 10 patients) days prior to start of FRT and three post-FRT examinations were performed 3.1 (3.3, 9 patients), 34.4 (9.5, 5 patients) and 103.3 (12.9, 9 patients) days after end of FRT. Five patients were administrated temozolamide after FRTPost-1 and three patients after FRTPost-2. PCV and bevacizumab/lomustine were administrated after FRTPost-1 in two patients respectively.

Changes in nCBV and nCBF after radiation treatment

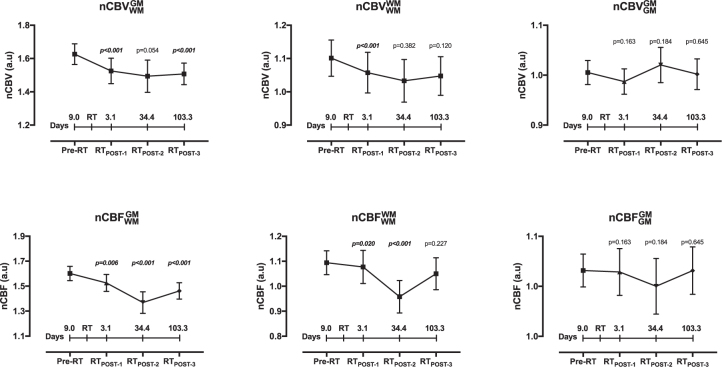

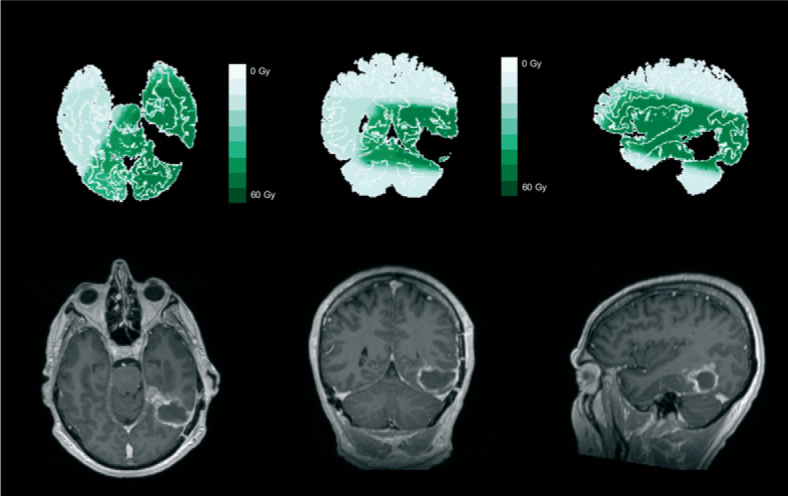

A representative dose region distribution map with corresponding pre-FRT 3D-T1w image are displayed in Figure 1. Global nCBV and nCBF with 95% CI and derived P-values are graphically described in Figure 2. Mean and SEM of global nCBV and nCBF together with mean relative change and SD and derived P-values are presented in Table 1. Both

Figure 1.

Dose region distribution with corresponding pre-fractionated radiotherapy (pre-FRT) Gd-T1w image. Representative dose region distribution with corresponding pre-FRT GD-T1w image for one patient. Dose distribution was divided into seven binary regions (0–5 Gy, 5–10 Gy, 10–20 Gy, 20–30 Gy, 30–40 Gy, 40–50 Gy and 50–60 Gy). Resection cavity, post-FRT effects and tumour tissue were excluded.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal change in global normalised cerebral blood volume (nCBV) and normalised cerebral blood flow (nCBF). Global nCBV and nCBF (mean and 95% CI) graphically displayed for the different examinations in consecutive order. Derived P-values are included, and emphasised in bold and italics if less than 0.05. Corresponding table for regional nCBV and nCBF can be found in S1 and S2 Figures.

Table 1.

Mean, standard error of mean (SEM) and change relative pre-fractionated radiotherapy (pre-FRT) for global nCBV and nCBF. Global normalised cerebral blood volume (nCBV) and normalised cerebral blood flow (nCBF) (mean and SEM), change in percentage relative pre-FRT (mean and SD) and derived P-values from a Wilcoxson matched-pair signed ranks test comparing post-FRT data with pre-FRT data. Corresponding table for regional nCBV and nCBF can be found in S2 Table

| Pre-FRT | FRTPost-1 | FRTPost-2 | FRTPost-3 | |

| ΔCBV | 1.63±0.03 | 1.53±0.04 | 1.49±0.05 | 1.53±0.03 |

| ΔnCBV (%) | -6.7±7.7 | -4.6±11.7 | -6.0±9.3 | |

| p-value | <0,0001 | 0,0535 | <0,0001 | |

| Pre-FRT | FRTPost-1 | FRTPost-2 | FRTPost-3 | |

| nCBF | 1.60±0.03 | 1.53±0.03 | 1.37±0.04 | 1.46±0.03 |

| ΔnCBF (%) | -5.1±11.7 | -12.5±11.4 | -7.5±8.2 | |

| p-value | 0,0057 | <0,0001 | <0,0001 | |

| Pre-FRT | FRTPost-1 | FRTPost-2 | FRTPost-3 | |

| nCBV | 1.10±0.03 | 1.06±0.03 | 1.03±0.03 | 1.05±0.03 |

| ΔnCBV (%) | -4.3±7.6 | 0.7±11.7 | -3.6±11.9 | |

| p-value | 0,0003 | 0,3818 | 0,1197 | |

| Pre-FRT | FRTPost-1 | FRTPost-2 | FRTPost-3 | |

| nCBF | 1.09±0.02 | 1.08±0.03 | 0.96±0.03 | 1.05±0.03 |

| ΔnCBF (%) | -3.1±7.7 | -7.4±10.5 | -3.4±10.3 | |

| p-value | 0,0166 | 0,0002 | 0,2267 | |

| Pre-FRT | FRTPost-1 | FRTPost-2 | FRTPost-3 | |

| nCBV | 1.00±0.01 | 0.99±0.01 | 1.02±0.02 | 1.0±0.02 |

| ΔnCBV (%) | -0.9±4.0 | 1.7±5.7 | -0.4±6.8 | |

| p-value | 0,1629 | 0,184 | 0,6445 | |

| Pre-FRT | FRTPost-1 | FRTPost-2 | FRTPost-3 | |

| nCBF | 1.02±0.01 | 1.01±0.01 | 1.00±0.01 | 1.02±0.01 |

| ΔnCBF (%) | -0.1±5.1 | -2.8±4.7 | 0.0±4.5 | |

| p-value | 0,4922 | 0,0073 | 0,9252 | |

and

decreased at FRTPost-1, decreased further at FRTPost-2, and recovered at FRTPost-3, however, still below corresponding values at pre-FRT. Significant differences were found for all values except

at FRTPost-2;

and

showed the same tendency. Only small variations between pre-FRT and post-FRT examinations were present in

and

implying no change after FRT. Comprehensive figures over regional nCBV and nCBF and derived P-values are provided in S1 and S2 Figures and S2 Table. In summary, similar responses were seen in regional nCBV and nCBF after FRT as in global nCBV and nCBF, but they were less pronounced and mostly non-significant.

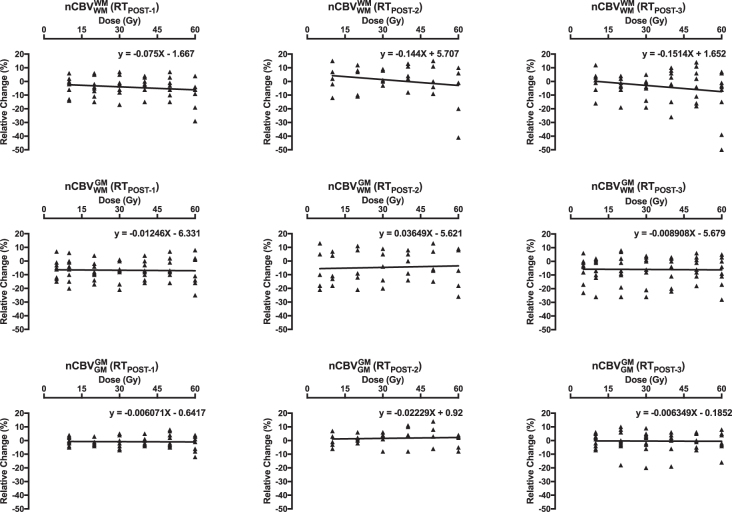

Dose-response relationship

Using a linear regression model, both

and

demonstrated an inverse response to radiation dose, i.e. larger reductions in nCBV with increasing radiation dose;

and

demonstrated a varied response to radiation dose. Furthermore, the same tendency could be seen for

and

.

In Figure 3, relative change and derived linear regression curve and equation for regional nCBV is illustrated (corresponding for nCBF can be found in S3 Figure).

Figure 3.

Dose-dependent relative change and linear regression model for normalised cerebral blood volume (nCBV). Shows regional relative change for nCBV and derived line regression (line and equation).

Corresponding figure for normalised cerebral blood flow (nCBF) can be found in S3 Figure.

Discussion

In this study, we found decreasing perfusion values indicating acute and early delayed effects in normal appearing brain tissue after FRT. We also observed a dose-response relationship in WM but not in GM.

Petr et al. reported a 9.8% decrease in contralateral normal appearing GM CBF measured with arterial spin labelling -MRI 4.8 months after FRT. An assessment of how the radiation dose given affects the decrease in CBF indicated that the decrease is larger with higher radiation dose i.e. an inverse dose-response relationship.10 A good correlation has previously been reported between arterial spin labelling -MRI and DSC-MRI with regard to measuring regional CBF13, 37, however, an analysis of white matter was not included. Price et al. found a dose-related decrease in relative CBV and relative CBF in normal appearing WM after FRT.11 However, only four patients were studied, and normalisation was performed to periventricular normal-appearing WM measured before FRT. Webber et al. reported no radiation-induced change in CBF, measured with DSC and arterial spin labelling MRI, after stereotactic radiosurgery in regions restricted to <0.5 Gy up to five times after FRT.13 Lee et al. studied CBV measured with DSC in WM and found a response that was similar to our results. The dose regions were larger, up to 60 Gy, in steps of 15 Gy. CBV was normalised to voxels receiving 0–15 Gy. A tendency towards an inverse dose-response relationship was reported.9 In summary, these results were in fair agreement with ours.

A number of contradictory findings have been reported in the literature. Jakubovic et al. evaluated relative CBV and relative CBF measured with DSC in patients undergoing single fraction stereotactic radiosurgery. They reported increasing rCBV and rCBF in both GM and WM.8 This discrepancy compared to our results can be explained by use of different radiation treatment methods and that normalisation was done only to pre-stereotactic radiosurgery CBV and CBF values. Fuss et al. evaluated CBV in GM and WM after FRT in patients with low-grade astrocytomas. Decrease of CBV up to 30% was seen 24 months after FRT in both GM and WM. Smaller decrease was seen 6 months after FRT.7 In another study, CBV change was evaluated 15 months after FRT in GM and WM. CBV after FRT was found to be significantly lower than before FRT.14 However, in both these studies, the DSC analysis was not described in detail, and the time period used in these studies did not coincide with ours. As absolute values were reported, the results presented in these studies could be affected largely by the limitations in absolute quantification of DSC-MRI-derived perfusion measures. Taki et al. reported a 7% decrease in global CBF in GM 2 weeks and 3 months after stereotactic radiosurgery. This is in agreement with our results. However, large decreases were detected in GM receiving < 5 Gy (up to 22%).12 This contradicting result could be explained by reproducibility errors between examinations. Non-normalised blood flow measured with 99mTc-HMPAO SPECT is affected by large variations between examinations compared to normalised blood flow.38 In this study, the authors do not describe if normalisation is used or not. Different radiation treatment methods and dose must also be considered as confounding factors when our results are compared with their findings.

Radiation-induced vascular structural changes, such as dilation and thickening of vessels, decreased vessel density, blood-brain-barrier disruption, endothelial cell damages may introduce thrombosis, tortuosity and occlusion. This could affect the perfusion and together with decreased vessel density and may partly explain our results.3, 4, 9 Furthermore, the recovery in nCBV and nCBF seen in our results agrees with the theory of acute and early delayed effects being reversible.1, 3, 4 However, radiation-induced changes in brain tissue is a complex process involving several tissue elements. Moreover, histopathology has mainly been studied in rodent models or single dose experiments.3, 5, 45 Interpreting findings from animal models and applying them to humans should be done with caution.

Our findings suggest that the GM response to the administrated treatment is independent of the radiation dose received; however, there is still an apparent reaction to radiation. This suggestion is based on two preliminary findings; first, a linear regression of relative difference in regional

and

demonstrated both positive and negative slopes, with small β values compared to WM tissue. Second, the resulting linear regression for

and

is also small and close to zero. This is to be expected if no dose-response relationship exists in GM, and furthermore, the use of radiation-induced changes in low-dose WM as reference tissue can be rejected as a confounding factor in this specific case because GM was used as the reference tissue. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to report a perfusion decrease independent of radiation dose in GM using DSC. Several publications have shown that grey matter volume decreases after fractionated radiotherapy increasing with radiation dose46, 47, 48, 49, since both CBV and CBF are tissue volume dependent parameters, we believe that the dose-independency found in grey matter is a result of decreased grey matter volume instead of an actual response in CBV and CBF independent on radiation dose given.

Despite encouraging results, some potential limitations need to be addressed. First, the patient number is small and for the evaluation of perfusion on examination FRTPost-2 only five data sets were analysed. The severity of the disease significantly contributed to the high number of excluded patients through drop-outs and terminating examinations, which was beyond our control. Our efforts to keep a consistent FRT protocol and imaging time frame also contributed to exclusions. However, since we investigated response to radiation dose over time, it was necessary to keep both radiation dose and imaging time point consistent in the patient material. Secondly, concomitant and adjuvant chemotherapy was given to all patients. While there are no reports of temozolomide or PCV affecting brain perfusion, a recent publication reported that bevacizumab may decrease CBF in contralateral normal appearing GM.50 However, only one patient was given bevacizumab during the examinations analysed, it is therefore unlikely that our data are affected by the adjuvant chemotherapy given.

The limitations of DSC-MRI are, in the present study, considered by several post-processing selections. The use of patient-specific AIF in DSC measurements has been shown to increase the reproducibility between examinations, minimising the effects on reproducibility inherent in partial volume effects and noise.51 This approach also confronts the concern regarding misleading results due to radiation-induced changes in pixels defined as the AIF.9 Vessel segmentation was performed to eliminate macro vessel signal contributions causing overestimation of CBV and CBF. We used pre-bolus administration and contrast agent leakage correction as suggested.15, 18 Furthermore, post-FRT effects such as oedema were excluded from the dose regions during segmentation, and can thereby not influence our results.

In summary, significant decrease of global nCBV and nCBF between pre-FRT and post-FRT examinations was found in our study. As proposed by Petr et al., perfusion variations in healthy tissue can represent a possible bias with regard to reference region selection.10 Acute and early delayed effects from FRT would, based on our results and other publications, introduce an overestimation of tumour CBV and CBF since the reference normal appearing brain tissue CBV and CBF are the denominator in the ratio. Thus, information from radiation dose plans may assist the selection of a reference WM region, avoiding GM to, if possible, define a region that received as low dose as possible.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that radiation-induced perfusion changes occur in normal-appearing brain tissue after FRT. This can cause an overestimation of relative tumour perfusion using DSC-MRI, and thus, can confound tumour treatment evaluation.

Acknowledgement

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily express an official position of the institution or funder. This work was funded by Bayer, AG, Berlin, Germany and the Swedish Cancer Society.

Disclosure

Professor Elna-Marie Larsson has received speaker honoraria from Bayer AG, Berlin, Germany. Remaining authors declared they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material.

References

- 1.Kim JH, Jenrow KA, Brown SL.. Mechanisms of radiation-induced normal tissue toxicity and implications for future clinical trials. Radiat Oncol J. 2014;32:103–15. doi: 10.3857/roj.2014.32.3.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price RE, Langford LA, Jackson EF, Stephens LC, Tinkey PT, Ang KK.. Radiation-induced morphologic changes in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) brain. J Med Primatol. 2001;30:81–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0684.2001.300202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sundgren PC, Cao Y.. Brain irradiation: effects on normal brain parenchyma and radiation injury. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2009;19:657–68. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greene-Schloesser D, Robbins ME, Peiffer AM, Shaw EG, Wheeler KT, Chan MD.. Radiation-induced brain injury: a review. Front Oncol. 2012;2:73. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao Y, Tsien CI, Sundgren PC, Nagesh V, Normolle D, Buchtel H. et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging as a biomarker for prediction of radiation-induced neurocognitive dysfunction. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1747–54. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adair JC, Baldwin N, Kornfeld M, Rosenberg GA.. Radiation-induced blood-brain barrier damage in astrocytoma: relation to elevated gelatinase B and urokinase. J Neurooncol. 1999;44:283–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1006337912345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuss M, Wenz F, Scholdei R, Essig M, Debus J, Knopp MV. et al. Radiation-induced regional cerebral blood volume (rCBV) changes in normal brain and low-grade astrocytomas: quantification and time and dose-dependent occurrence. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48:53–8. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(00)00590-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jakubovic R, Sahgal A, Ruschin M, Pejovic-Milic A, Milwid R, Aviv RI.. Non tumor perfusion changes following stereotactic Radiosurgery to brain metastases. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2014 doi: 10.7785/tcrtex-press.2013.600279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee MC, Cha S, Chang SM, Nelson SJ.. Dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion imaging of radiation effects in normal-appearing brain tissue: changes in the first-pass and recirculation phases. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;21:683–93. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petr J, Platzek I, Seidlitz A, Mutsaerts HJ, Hofheinz F, Schramm G. et al. Early and late effects of radiochemotherapy on cerebral blood flow in glioblastoma patients measured with non-invasive perfusion MRI. Radiother Oncol. 2016;118:24–8. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Price SJ, Jena R, Green HA, Kirkby NF, Lynch AG, Coles CE. et al. Early radiotherapy dose response and lack of hypersensitivity effect in normal brain tissue: a sequential dynamic susceptibility imaging study of cerebral perfusion. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2007;19:577–87. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taki S, Higashi K, Oguchi M, Tamamura H, Tsuji S, Ohta K. et al. Changes in regional cerebral blood flow in irradiated regions and normal brain after stereotactic radiosurgery. Ann Nucl Med. 2002;16:273–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber MA, Gunther M, Lichy MP, Delorme S, Bongers A, Thilmann C. et al. Comparison of arterial spin-labeling techniques and dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI in perfusion imaging of normal brain tissue. Invest Radiol. 2003;38:712–8. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000084890.57197.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wenz F, Rempp K, Hess T, Debus J, Brix G, Engenhart R. et al. Effect of radiation on blood volume in low-grade astrocytomas and normal brain tissue: quantification with dynamic susceptibility contrast MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:187–93. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.1.8571873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paulson ES, Schmainda KM.. Comparison of dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced MR methods: recommendations for measuring relative cerebral blood volume in brain tumors. Radiology. 2008;249:601–13. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2492071659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jafari-Khouzani K, Emblem KE, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Bjornerud A, Vangel MG, Gerstner ER. et al. Repeatability of cerebral perfusion using dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI in glioblastoma patients. Transl Oncol. 2015;8:137–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Law M, Young RJ, Babb JS, Peccerelli N, Chheang S, Gruber ML. et al. Gliomas: predicting time to progression or survival with cerebral blood volume measurements at dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging. Radiology. 2008;247:490–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2472070898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lacerda S, Law M.. Magnetic resonance perfusion and permeability imaging in brain tumors. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2009;19:527–57. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarnum H, Steffensen EG, Knutsson L, Frund ET, Simonsen CW, Lundbye-Christensen S. et al. Perfusion MRI of brain tumours: a comparative study of pseudo-continuous arterial spin labelling and dynamic susceptibility contrast imaging. Neuroradiology. 2010;52:307–17. doi: 10.1007/s00234-009-0616-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi SH, Jung SC, Kim KW, Lee JY, Choi Y, Park SH. et al. Perfusion MRI as the predictive/prognostic and pharmacodynamic biomarkers in recurrent malignant glioma treated with bevacizumab: a systematic review and a time-to-event meta-analysis. J Neurooncol. 2016;128:185–94. doi: 10.1007/s11060-016-2102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vogelbaum MA, Jost S, Aghi MK, Heimberger AB, Sampson JH, Wen PY. et al. Application of novel response/progression measures for surgically delivered therapies for gliomas: Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) Working Group. Neurosurgery. 2012;70:234–43. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318223f5a7. discussion 43-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tensaouti F, Khalifa J, Lusque A, Plas B, Lotterie JA, Berry I. et al. Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology criteria, contrast enhancement and perfusion MRI for assessing progression in glioblastoma. Neuroradiology. 2017;59:1013–20. doi: 10.1007/s00234-017-1899-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bjornerud A, Emblem KE.. A fully automated method for quantitative cerebral hemodynamic analysis using DSC-MRI. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1066–78. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.4. Epub 2010/01/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knutsson L, Stahlberg F, Wirestam R.. Absolute quantification of perfusion using dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI: pitfalls and possibilities. MAGMA. 2010;23:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s10334-009-0190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mouridsen K, Christensen S, Gyldensted L, Ostergaard L.. Automatic selection of arterial input function using cluster analysis. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:524–31. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersen ET, Zimine I, Ho YC, Golay X.. Non-invasive measurement of perfusion: a critical review of arterial spin labelling techniques. Br J Radiol. 2006;79:688–701. doi: 10.1259/bjr/67705974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emblem KE, Bjornerud A.. An automatic procedure for normalization of cerebral blood volume maps in dynamic susceptibility contrast-based glioma imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:1929–32. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ. et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ostergaard L.. Principles of cerebral perfusion imaging by bolus tracking. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;22:710–7. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simonsen CZ, Ostergaard L, Vestergaard-Poulsen P, Rohl L, Bjornerud A, Gyldensted C.. CBF and CBV measurements by USPIO bolus tracking: reproducibility and comparison with Gd-based values. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;9:342–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2586(199902)9:2<342::AID-JMRI29>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emblem KE, Bjornerud A, Mouridsen K, Borra RJ, Batchelor TT, Jain RK. et al. T(1)- and T(2)(∗)-dominant extravasation correction in DSC-MRI: part II-predicting patient outcome after a single dose of cediranib in recurrent glioblastoma patients. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:2054–64. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ostergaard L, Sorensen AG, Kwong KK, Weisskoff RM, Gyldensted C, Rosen BR.. High resolution measurement of cerebral blood flow using intravascular tracer bolus passages. Part II: Experimental comparison and preliminary results. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36:726–36. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calamante F, Gadian DG, Connelly A.. Quantification of bolus-tracking MRI: improved characterization of the tissue residue function using Tikhonov regularization. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:1237–47. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boxerman JL, Schmainda KM, Weisskoff RM.. Relative cerebral blood volume maps corrected for contrast agent extravasation significantly correlate with glioma tumor grade, whereas uncorrected maps do not. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:859–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emblem KE, Due-Tonnessen P, Hald JK, Bjornerud A.. Automatic vessel removal in gliomas from dynamic susceptibility contrast imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:1210–7. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klein S, Staring M, Murphy K, Viergever MA, Pluim JP.. Elastix: a toolbox for intensity-based medical image registration. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2010;29:196–205. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2009.2035616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.White CM, Pope WB, Zaw T, Qiao J, Naeini KM, Lai A. et al. Regional and voxel-wise comparisons of blood flow measurements between dynamic susceptibility contrast magnetic resonance imaging (DSC-MRI) and arterial spin labeling (ASL) in brain tumors. J Neuroimaging. 2014;24:23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2012.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jonsson C, Pagani M, Johansson L, Thurfjell L, Jacobsson H, Larsson SA.. Reproducibility and repeatability of 99Tcm-HMPAO rCBF SPET in normal subjects at rest using brain atlas matching. Nucl Med Commun. 2000;21:9–18. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200001000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li YQ, Chen P, Haimovitz-Friedman A, Reilly RM, Wong CS.. Endothelial apoptosis initiates acute blood-brain barrier disruption after ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5950–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lyubimova N, Hopewell JW.. Experimental evidence to support the hypothesis that damage to vascular endothelium plays the primary role in the development of late radiation-induced CNS injury. Br J Radiol. 2004;77:488–92. doi: 10.1259/bjr/15169876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cao Y, Tsien CI, Shen Z, Tatro DS, Ten Haken R, Kessler ML. et al. Use of magnetic resonance imaging to assess blood-brain/blood-glioma barrier opening during conformal radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4127–36. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown WR, Thore CR, Moody DM, Robbins ME, Wheeler KT.. Vascular damage after fractionated whole-brain irradiation in rats. Radiat Res. 2005;164:662–8. doi: 10.1667/rr3453.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coderre JA, Morris GM, Micca PL, Hopewell JW, Verhagen I, Kleiboer BJ. et al. Late effects of radiation on the central nervous system: role of vascular endothelial damage and glial stem cell survival. Radiat Res. 2006;166:495–503. doi: 10.1667/RR3597.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong CS, Van der Kogel AJ.. Mechanisms of radiation injury to the central nervous system: implications for neuroprotection. Mol Interv. 2004;4:273–84. doi: 10.1124/mi.4.5.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuan H, Gaber MW, Boyd K, Wilson CM, Kiani MF, Merchant TE.. Effects of fractionated radiation on the brain vasculature in a murine model: blood-brain barrier permeability, astrocyte proliferation, and ultrastructural changes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:860–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prust MJ, Jafari-Khouzani K, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Polaskova P, Batchelor TT, Gerstner ER. et al. Standard chemoradiation for glioblastoma results in progressive brain volume loss. Neurology. 2015;85:683–91. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karunamuni RA, Moore KL, Seibert TM, Li N, White NS, Bartsch H. et al. Radiation sparing of cerebral cortex in brain tumor patients using quantitative neuroimaging. Radiother Oncol. 2016;118:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petr J, Platzek I, Hofheinz F, Mutsaerts H, Asllani I, van Osch MJP. et al. Photon vs. proton radiochemotherapy: effects on brain tissue volume and perfusion. Radiother Oncol. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karunamuni R, Bartsch H, White NS, Moiseenko V, Carmona R, Marshall DC. et al. Dose-dependent cortical thinning after partial brain irradiation in highgrade glioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;94:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andre JB, Nagpal S, Hippe DS, Ravanpay AC, Schmiedeskamp H, Bammer R. et al. Cerebral blood flow changes in glioblastoma patients undergoing bevacizumab treatment are seen in both tumor and normal brain. [Abstract] Neuroradiol J. 2015;28:112–9. doi: 10.1177/1971400915576641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mouridsen K, Emblem K, Bjørnerud A, Jennings D, Sorensen AG.. Subject-specific AIF optimizes reproducibility of perfusion parameters in longitudinal DSC-MRI. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med. 2011;19:376. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.