Short abstract

Fluoro-Jade is a fluorescein-derived fluorochrome which specifically binds to damaged neurons. Due to this characteristic, it is commonly used for the histochemical detection and quantification of neurodegeneration in mounted brain sections. Here, we describe an alternative and simpler histochemistry protocol based on the use of free-floating brain sections. For this purpose, we have used brain slices from wild-type and 5xFAD mice as well as from mice that received an intracerebral injection of oligomeric amyloid beta peptides. We observed that our histochemistry staining procedure allows for a well-defined labeling of degenerating neurons providing a better signal-to-noise ratio staining than the commonly used one. In addition, our modified protocol demonstrates the ability of Fluoro-Jade C to also fluorescently label amyloid beta plaques.

Keywords: Alzheimer, Fluoro-Jade, histochemistry, Western blot

Introduction

The development of tools that allow for the evaluation of neuronal viability has always been one of the main objectives of neuroscience. Due to this, different strategies have been used to achieve this goal. The most commonly used markers such as Golgi silver impregnation, Nissl, or hematoxylin and eosin have a limited specificity and rely largely on the detection of characteristic morphological changes produced when neurons are damaged (Fischer et al., 2008; Pilati et al., 2008). In addition, antibodies synthetized against specific neuronal proteins such as neuronal nuclei (Gusel'nikova and Korzhevskiy, 2015), neuron-specific enolase (Kirino et al., 1983), or microtubule-associated protein 2 (Johnson and Jope, 1992) had been used in order to quantify the number of neurons present in a particular brain area and evaluate this way how different conditions affect their survival.

An alternative approach consists of co-immunostaining with neuronal markers, such as the ones indicated earlier, and other markers known to label apoptotic cells (such as annexin V or caspase 3) or cells undergoing autophagy (such as beclin 1, Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3, or other autophagy related proteins; Guillemain et al., 2003; Carloni et al., 2008; Sabri et al., 2008). In this way, those cells that present staining with both markers can be categorized as degenerating neurons. The main advantage of this technique is that the detection of proteins synthesized during apoptotic or autophagic processes allows to objectively confirm the degeneration of the cells, instead of basing this conclusion on morphological alterations or changes in the staining pattern achieved by the aforementioned techniques, which is a more subjective way of assessing neuronal death and can, therefore, facilitate an incorrect quantification of neurodegeneration. However, the need for two specific primary antibodies increases the complexity of the procedure and can also lead to more imprecise or erroneous results.

Therefore, the development of a dye such as Fluoro-Jade (FJ), which specifically labels degenerating neurons, represented a significant advance for this area of research (Schmued et al., 1997). The use of FJ is a simple and consistent procedure to label degenerating neurons. Consequently, it has been used in multiple studies and is widely accepted as a reliable marker even in unfixed tissue (Gu et al., 2012).

This has led to the further refinement of the molecule and to the synthesis of two additional variants, FJ-B first and FJ-C latter, each one with an improved signal-to-background ratio and higher resolution than its predecessor (Schmued and Hopkins, 2000; Schmued et al., 2005).

The possibility of detecting FJ staining even after its combination with other fluorescent or nonfluorescently labeled secondary antibodies constitutes another one of its main advantages.

The exact nature of the mechanism through which FJ labels certain neurons is not known; however, the authors who developed FJ propose that a cleaved form of the microtubule protein tau is a possible binding target for FJ (Schmued et al., 2005).

The technique commonly used for FJ staining requires the previous mounting of brain sections on slides, being this followed by the drying and subsequent rehydration of the tissue. Here, we describe an alternative protocol based on the use of free-floating brain sections which results in a more intense staining of neurons and a reduced background signal.

In addition, based on previous studies that demonstrated FJ-B ability to label amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques (Damjanac et al., 2007), we have analyzed if this also occurs for the more specific FJ-C.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 and 5xFAD mice of 6 months of age weighing 30 to 35 g were used. All experimental protocols adhered to the guidelines of the Animal Welfare Committee of the Universidad Complutense of Madrid, Spain (PROEX 052/17), and according to European Union laws (2010/63/EU). All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to reduce the number of animals used. The mice were housed in a 12-h light/dark cycle under standard temperature and humidity conditions, with free access to food and water.

5xFAD mice (Oakley et al., 2006) harbor three mutations in the amyloid precursor protein gene and two in the presenilin-1 gene; they accumulate soluble Aβ, develop plaques by 4 to 5 weeks of age, and show frank neuronal damage including intraneuronal accumulation of Aβ1–42 and cognitive deficits by 5 months of age. Mice were generated by crossing male heterozygous 5xFAD mice to WT C57BL/6 female mice, followed by polymerase chain reaction analysis for the presence of the amyloid precursor protein transgene.

At 6 months of age, mice were anesthetized and perfused via the ascending aorta with 0.1M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer, pH 7.4. The brains were removed, one hemibrain was dissected, cortical areas excised from the brain, snap-frozen, and kept at −80°C for isolation of proteins. The other half was postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and cryoprotected in 15% sucrose during the following 24 h. After this, regularly spaced series of 25-μm-thick coronal sections were collected in cryoprotectant solution and stored at −20°C until processing.

Intracerebral Injection of Aβ

Male WT C57BL/6 mice of 3 months of age weighing 30 to 35 g were used. Oligomeric Aβ1-42 was prepared as described earlier (Kalinin et al., 2006).

Mice were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (10 mg/kg body weight) and xylazine (20 mg/kg body weight) in saline solution. Stereotaxic injections of 1 μl of Aβ1-42 at a concentration of 100 μM were placed with a Hamilton syringe into the cortex (A/P, +1.0 mm from bregma; L, ±1.5 mm; D/V, −1 mm). The rate of injection was 1 μl/min, and the needle was kept in place for 3 min before it was slowly withdrawn. The surgical area was cleaned with sterile saline solution, the incision was sutured, and the mice were monitored until recovery from anesthesia. One week later, mice were sacrificed and brain tissue processed as indicated earlier.

Fluorojade C Staining of Mounted Brain Sections: Conventional Protocol

Following the instructions described by Schmued et al. (2005), the brain sections were mounted onto slides from distilled water and air-dried for 30 min on a slide warmer at 50°C. After this, they were first immersed in a basic alcohol solution consisting of 1% sodium hydroxide in 80% ethanol for 5 min, then 2 min in 70% ethanol and 2 min in distilled water; followed by 10 min in a solution of 0.06% potassium permanganate. They were rinsed in distilled water and stained for 10 min in a 0.0001% solution of FJ-C (AG325, Merck) made in 0.1% acetic acid. The proper dilution was accomplished by first making a 0.01% stock solution of the dye in distilled water and then adding 1 ml of the stock solution to 99 ml of 0.1% acetic acid vehicle. The working solution was used within 2 h of preparation. The slides were then rinsed through three changes of distilled water for 1 min per change. Excess water was drained onto a paper towel, and the slides were then air-dried on a slide warmer at 50°C for at least 5 min. The air-dried slides were then cleared in xylene for 1 min and then coverslipped with Fluoroshied™ with DAPI (Sigma).

Images were obtained on a Nikon Eclipse Ti-S microscope equipped with a Digital Sight digital camera and NIS-elements imaging software.

FJ-C Staining of Free-Floating Brain Sections: Alternative Protocol

The brain sections, prepared as described earlier, were transferred to separate wells containing 500 μl of PBS in a 24-well plate. After 5 min, the sections were transferred to different wells containing PBS. This process was repeated one more time for a total of three PBS washes. After this, the sections were incubated in a 0.001% solution of FJ-C made in PBS for 10 min. The sections were then washed 3 times in PBS (5 min each), and autofluorescence was quenched with 50 mM NH4Cl in PBS for 15 min. Finally, after three additional PBS washes (3 min each), they were mounted onto slides from PBS and then coverslipped with Fluoroshied™ with DAPI (Sigma). Images were obtained on a Nikon Eclipse Ti-S microscope equipped with a Digital Sight digital camera and NIS-elements imaging software. See Table 1 for details.

Table 1.

Description of the Steps Involved in the Two Staining Protocols Used.

| Conventional protocol | Time (min) | Alternative protocol | Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mount sections | PBS wash, 3 × 5 min | 15 | |

| Dry at 50°C | 30 | Fluoro-Jade C (0.001%) | 10 |

| NaOH + EtOH | 5 | PBS wash, 3 × 5 min | 15 |

| 70% EtOH | 2 | NH4Cl | 15 |

| Water | 2 | PBS wash, 3 × 5 min | 15 |

| KMnO4 | 10 | Mount sections | |

| Water rinse | Coverslip | ||

| Fluoro-Jade C (0.0001%) | 10 | ||

| Water rinse, 3 × 1 min | 3 | ||

| Dry 50°C | <5 | ||

| Xylene | 1 | ||

| Coverslip |

Note. Main differences are indicated in boldface. PBS = phosphate-buffered saline.

Double Immunohistochemistry With FJ-C

The sections were washed with PBS 3 times for 5 min. After this, they were incubated in a 0.001% solution of FJ-C made in PBS for 10 min. The sections were then washed with PBS 3 times for 5 min, and they were blocked with 10% normal goat serum and 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS at 25°C for 1 h. Next, they were incubated with primary antibodies (rabbit anti-β-amyloid, ab2539) diluted 1:500 in 1% normal goat serum and 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS at 4°C for 18 h. After this, the sections were washed 3 times with PBS and incubated for 1 h at 25°C with Dylight 650 goat antirabbit (ab96898, Abcam), diluted 1:500 in PBS with 1% normal goat serum. Then, they were washed 3 times for 5 min with PBS, and autofluorescence was quenched with 50 mM NH4Cl in PBS for 15 min. Finally, after washing the sections with PBS for 3 min, they were mounted onto the slides from PBS and then coverslipped with Fluoroshied™ with DAPI (Sigma).

When immunostaining was performed exclusively for Aβ, the same procedure was followed omitting the first washes and the FJ-C incubation.

Images were obtained on a Nikon Eclipse Ti-S microscope equipped with a Digital Sight digital camera and with a Leica SP8 confocal microscope equipped with a Leica DFC350FX digital camera.

Results

Comparison of Both FJ Staining Protocols in 5xFAD Samples

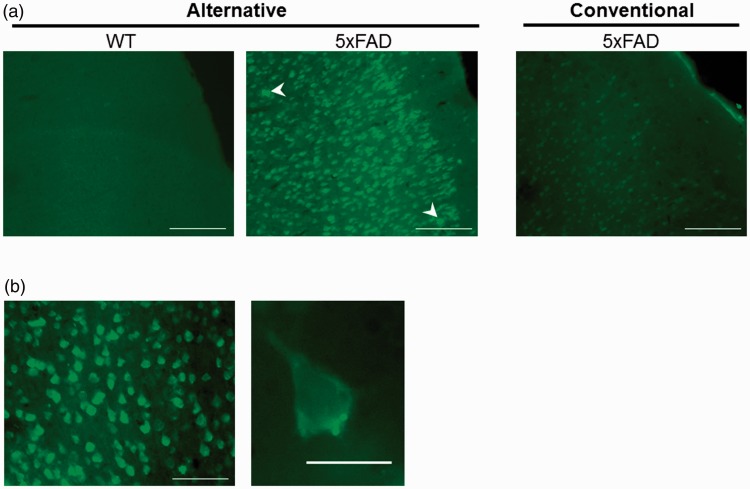

Given the convenience of FJ staining as a way to detect neuronal degeneration, we have tested different histochemical procedures with the aim of being able to use free-floating sections and to simplify the procedure. In this way, we applied the conventional staining protocol and our modified version of it to brain sections obtained from WT and 5xFAD mice. The results obtained with both protocols indicate that the use of the alternative protocol described earlier results in a brighter signal from the labeled cells when compared with the staining achieved by the use of the protocol recommended by the manufacturer and commonly used (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The use of an alternative protocol improves Fluoro-Jade C labeling of damaged neurons. (a) Representative images of the frontal cortex (primary somatosensory area layer 1) from consecutive sections prepared from 5xFAD and WT mice stained with Fluoro-Jade C following the free-floating (alternative) and mounted sections (conventional) procedures described. Scale bars correspond to 100 μm. High-intensity spots are indicated with arrowheads. (b) Higher magnification allows to notice the characteristic neuronal morphology of the cells stained. Scale bars correspond to 50 μm (left) and 10 μm (right). WT = wild type.

Application of the Modified Protocol in Brain Samples From Aβ Injected Mice

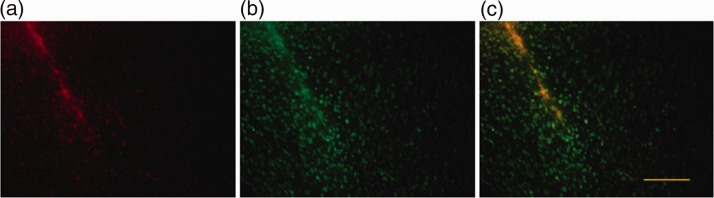

To analyze the ability of the alternative protocol to detect neurodegeneration in a different model of injury, intracerebral injections of Aβ were performed in WT mice. The brain sections containing the cortical area surrounding the injection site were processed following our alternative protocol.

The costaining with FJ- and Aβ-specific antibodies resulted in a specific staining of cells surrounding the area where Aβ was injected (Figure 2). This indicates that, also in this injury model, the modified protocol allows for a specific staining of damaged neurons.

Figure 2.

Alternative protocol used for the detection of neurodegeneration caused by intracerebral injection of Aβ. Representative images corresponding to the Aβ injection area stained with Aβ (a) and Fluoro-Jade C (b). (c) Double staining for Fluoro-Jade C and Aβ. Scale bar corresponds to 100 μm.

Interestingly, double labeling suggests that FJ stains a molecule in or near to the sites of Aβ staining (Figure 2(c)), suggesting that FJ also interacts with the oligomeric form of Aβ that was administered to the mice.

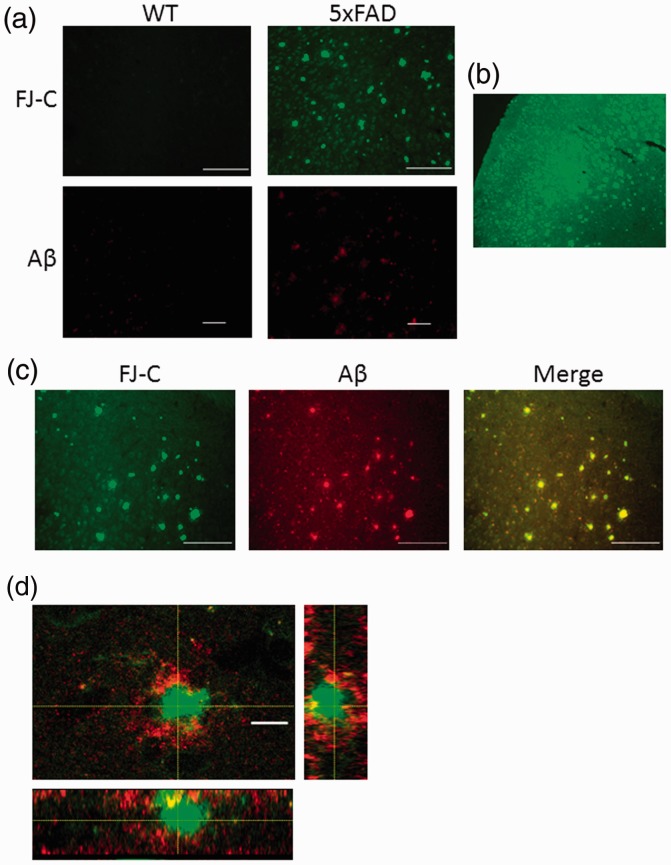

Detection of Aβ Plaques With FJ-C

The detection of certain spots with very intense fluorescence and irregular shapes in addition to the signal provided by stained neurons in 5xFAD samples (arrowheads in Figure 1(a)) as well as the staining observed for FJ-C and Aβ in the sections from Aβ injected mice led us to consider the possible staining of amyloid plaques by FJ-C. These spots were more densely present in deeper brain areas (Figure 3(b)). In this way, the analysis of these areas allowed us to notice that these bright spots were distributed in a pattern similar to the amyloid plaques and could not be detected in the samples obtained from WT mice (Figure 3(a)). The proximity of both types of fluorescent signals found after the double labeling with FJ-C and an Aβ antibody (Figure 3(c) and (d)) confirmed that the staining detected corresponds to Aβ plaques. This also reveals the potential of FJ-C as an alternative strategy to detect the accumulation of Aβ.

Figure 3.

FJ-C labels Aβ plaques. (a) Representative images of the frontal cortex (primary somatosensory area layer 5) from sections prepared from WT or 5xFAD mice stained with FJ-C (green) or β amyloid (red) following the free-floating sections procedure described. Scale bars correspond to 100 μm (FJ) and 50 μm (Aβ). (b) Low-magnification image (10×) from a FJ-C stained 5xFAD section where the distribution of high-intensity fluorescent spots can be seen. (c) Double staining for FJ-C and β amyloid in sections prepared from 5xFAD mice. Scale bars correspond to 100 μm. (d) Colocalization of Aβ (red) and FJ-C (green). Dashed lines indicate the cutting planes for the corresponding cross-sectional images. Scale bar corresponds to 7 μm. J-C = Fluoro-Jade C; Aβ = amyloid beta; WT = wild type.

However, FJ-C staining does not overlap with smaller deposits of Aβ that are detected by immunostaining (red areas in the merged image of Figure 3(c)). This indicates that the sensitivity of FJ-C for Aβ may be lower in comparison with other markers.

Discussion

FJ is a very useful tool that helps to detect and quantify neuronal degeneration in brain samples. For this reason, like many other dyes and reagents used to visualize cellular alterations in tissue samples, continuous efforts are made by the manufacturers and users of these reagents with the goal of increasing their effectiveness. This is achieved by introducing modifications in the product as well as in the ways to use it in order to achieve different improvements. These include increases in the resolution of the signal provided, shortenings of the time requested to obtain data, or even the reduction of the modifications caused to the samples so that they can be used for additional analyses.

The procedure commonly used to stain brain sections with FJ requires the mounting of the section being this followed by drying, rehydration, and permeabilization steps (Schmued et al., 1997).

We observed that this procedure, while effective, causes a considerable deterioration of the tissue, hindering sometimes the analysis of parts of the area to be analyzed.

For this reason, we decided to test whether alternative ways to use FJ were feasible. Previous studies demonstrate that the usual protocol can be modified using unfixed brain samples (Gu et al., 2012). In addition, we had also demonstrated that FJ can also be applied to neuronal cultures (Madrigal et al., 2007) being this an alternative strategy to detect and quantify neuronal damage by visualization of the cells. This last procedure was confirmed 7 years later by other authors who were not aware of our previous work (Gu et al., 2014).

Based on this, we tested the possibility of using free-floating sections and to stain them with FJ-C. First, we reproduced all the steps from the conventional protocol omitting the mounting and drying of the slides, but this resulted in a very strong background signal. Therefore, we tested the effects of removing different steps of the protocol. In this way, we observed that the removal of the permeabilization and permanganate steps reduced the tissue damage, but the signal was not very intense. Next, we tested the possibility of compensating this by increasing the concentration of FJ, until we found the conditions here described to be the ones that gave us the best results.

The main goals pursued with these modifications were to reduce the deterioration of the samples caused by the different treatments performed during the protocol, to simplify the procedure, and to facilitate the penetration of the dye into the tissue by allowing it to interact with both sides of the section. We were satisfied to discover that not only we accomplished all of our goals, but we were also able to achieve a more intense and better defined stain of the damaged neurons with a higher signal-to-noise ratio. One of the factors that may contribute to these differences is the use of free-floating sections, and the better penetration of the dye achieved this way, in comparison to mounted sections. Another significant difference between both protocols is the higher concentration of the dye used in ours. This was empirically determined and suggests that the avoidance of the dehydration–rehydration steps reduces the permeability of the tissue. Correspondingly, this lack of permeabilization may also contribute to reducing the background unspecific staining. However, alternative permeabilization methods which do not damage the tissue may be explored in order to further improve the staining protocol.

Six months old 5xFAD mice were selected because at that age these mice present a large degree of neuronal death. This resulted in a wide distribution of FJ staining in all cortical areas examined.

The detection of a similar fluorescent signal in the samples obtained from mice that received intracerebral injections of Aβ confirms the usefulness of our alternative staining technique.

One of the most interesting characteristics of the staining pattern observed in 5xFAD samples was the presence of areas with very bright fluorescence and clearly different from the neuronal bodies as could be inferred from their size and shapes. The double labeling with specific antibodies indicates that these elements are Aβ plaques. This is in agreement with the similar effect previously described for the less specific FJ-B (Damjanac et al., 2007). Moreover, this analysis demonstrates that our FJ-C staining protocol can be combined with the immunohistochemical detection of other proteins in the same brain section. Interestingly, proximal staining for Aβ and FJ was also found when Aβ was administered by directly injecting it into brain cortex. In this case, we know that Aβ was in an oligomeric form. This indicates that FJ-C interacts not only with larger aggregates of this protein but also with smaller forms of it. But, since in normal conditions Aβ oligomers are not so condensed as in the case of the administration here performed, the fluorescent signal provided by FJ may be more diffused and, thus, more difficult to detect and identify. Also, the injected Aβ oligomers may dissociate to monomers which may not be able to interact so strongly with FJ-C. This could explain the reduced overlap observed in this case in comparison to the larger Aβ plaques present in the brains from 5xFAD mice.

Nevertheless, this fact suggests that FJ-C may also be able to bind and label similar protein aggregates like the ones occurring in other neurodegenerative conditions such as Huntington’s or Parkinson’s disease. In fact, it has been demonstrated to label Rosenthal fibers (Tanaka et al., 2006; Sosunov et al., 2017), a proteinaceous aggregate characteristic of Alexander’s disease. Therefore, the potential of FJ as a tool for the diagnosis of different neurological disorders in which protein aggregates occur should be further analyzed.

Summary

In this study, we describe alternative ways to detect neurodegeneration in brain samples. For this purpose, we use a fluorescent dye that specifically labels damaged neurons.

Author Contributions

I. L. G. and J. L. M. M. planned and conducted the experiments. All authors contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, and revising it critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Universidad Complutense de Madrid (PR26/16-20278), the Spanish Ministry of Science (SAF2017-86620-R), and Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental. M. G. P. was supported by a Fellowship from the European Youth Employment Initiative. J. R. C. is a Ramón y Cajal fellow (Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Competitiveness).

References

- Carloni S., Buonocore G., Balduini W. (2008). Protective role of autophagy in neonatal hypoxia-ischemia induced brain injury. Neurobiol Dis, 32, 329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damjanac M., Rioux B. A., Barrier L., Pontcharraud R., Anne C., Hugon J., Page G. (2007). Fluoro-Jade B staining as useful tool to identify activated microglia and astrocytes in a mouse transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res, 1128, 40–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A. H., Jacobson K. A., Rose J., Zeller R. (2008). Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue and cell sections. Cold Spring Harb Protoc, 3, 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q., Lantz-McPeak S., Rosas-Hernandez H., Cuevas E., Ali S. F., Paule M. G., Sarkar S. (2014). In vitro detection of cytotoxicity using FluoroJade-C. Toxicol In Vitro, 28, 469–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q., Schmued L. C., Sarkar S., Paule M. G., Raymick B. (2012). One-step labeling of degenerative neurons in unfixed brain tissue samples using Fluoro-Jade C. J Neurosci Methods, 208, 40–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemain I., Fontes G., Privat A., Chaudieu I. (2003). Early programmed cell death in human NT2 cell cultures during differentiation induced by all-trans-retinoic acid. J Neurosci Res, 71, 38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusel'nikova V. V., Korzhevskiy D. E. (2015). NeuN as a neuronal nuclear antigen and neuron differentiation marker. Acta Naturae, 7, 42–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G. V., Jope R. S. (1992). The role of microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP-2) in neuronal growth, plasticity, and degeneration. J Neurosci Res, 33, 505–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinin S., Polak P. E., Madrigal J. L., Gavrilyuk V., Sharp A., Chauhan N., Marien M., Colpaert F., Feinstein D. L. (2006). Beta-amyloid-dependent expression of NOS2 in neurons: Prevention by an alpha2-adrenergic antagonist. Antioxid Redox Signal, 8, 873–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirino T., Brightman M. W., Oertel W. H., Schmechel D. E., Marangos P. J. (1983). Neuron-specific enolase as an index of neuronal regeneration and reinnervation. J Neurosci, 3, 915–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrigal J. L., Kalinin S., Richardson J. C., Feinstein D. L. (2007). Neuroprotective actions of noradrenaline: Effects on glutathione synthesis and activation of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor delta. J Neurochem, 103, 2092–2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley H., Cole S. L., Logan S., Maus E., Shao P., Craft J., Guillozet-Bongaarts A., Ohno M., Disterhoft J., Van Eldick L., Berry R., Vassar R. (2006). Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: Potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J Neurosci, 26, 10129–10140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilati N., Barker M., Panteleimonitis S., Donga R., Hamann M. (2008). A rapid method combining Golgi and Nissl staining to study neuronal morphology and cytoarchitecture. J Histochem Cytochem, 56, 539–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabri M., Kawashima A., Ai J., Macdonald R. L. (2008). Neuronal and astrocytic apoptosis after subarachnoid hemorrhage: A possible cause for poor prognosis. Brain Res, 1238, 163–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmued L. C., Albertson C., Slikker W., Jr(1997). Fluoro-Jade: A novel fluorochrome for the sensitive and reliable histochemical localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain Res, 751, 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmued L. C., Hopkins K. J. (2000). Fluoro-Jade B: A high affinity fluorescent marker for the localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain Res, 874, 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmued L. C., Stowers C. C., Scallet A. C., Xu L. (2005). Fluoro-Jade C results in ultra high resolution and contrast labeling of degenerating neurons. Brain Res, 1035, 24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosunov A. A., McKhann G. M., Goldman J. E. (2017). The origin of Rosenthal fibers and their contributions to astrocyte pathology in Alexander disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun, 5, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K. F., Ochi N., Hayashi T., Ikeda E., Ikenaka K. (2006). Fluoro-Jade: New fluorescent marker of Rosenthal fibers. Neurosci Lett, 407, 127–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]