Abstract

Background

Screening is an important part of preventive medicine. Ideally, screening tools identify patients early enough to provide treatment and avoid or reduce symptoms and other consequences, improving health outcomes of the population at a reasonable cost. Cost-effectiveness analyses combine the expected benefits and costs of interventions and can be used to assess the value of screening tools.

Objective

This review seeks to evaluate the latest cost-effectiveness analyses on screening tools to identify the current challenges encountered and potential methods to overcome them.

Methods

A systematic literature search of EMBASE and MEDLINE identified cost-effectiveness analyses of screening tools published in 2017. Data extracted included the population, disease, screening tools, comparators, perspective, time horizon, discounting, and outcomes. Challenges and methodological suggestions were narratively synthesized.

Results

Four key categories were identified: screening pathways, pre-symptomatic disease, treatment outcomes, and non-health benefits. Not all studies included treatment outcomes; 15 studies (22%) did not include treatment following diagnosis. Quality-adjusted life years were used by 35 (51.4%) as the main outcome. Studies that undertook a societal perspective did not report non-health benefits and costs consistently. Two important challenges identified were (i) estimating the sojourn time, i.e., the time between when a patient can be identified by screening tests and when they would have been identified due to symptoms, and (ii) estimating the treatment effect and progression rates of patients identified early.

Conclusions

To capture all important costs and outcomes of a screening tool, screening pathways should be modeled including patient treatment. Also, false positive and false negative patients are likely to have important costs and consequences and should be included in the analysis. As these patients are difficult to identify in regular data sources, common treatment patterns should be used to determine how these patients are likely to be treated. It is important that assumptions are clearly indicated and that the consequences of these assumptions are tested in sensitivity analyses, particularly the assumptions of independence of consecutive tests and the level of patient and provider compliance to guidelines and sojourn times. As data is rarely available regarding the progression of undiagnosed patients, extrapolation from diagnosed patients may be necessary.

Keywords: Screening, Cost-effectiveness analysis, Value, Pre-symptomatic disease

Background

Screening represents a cornerstone of preventive medicine. Its rationale is to identify disease during an early and pre-symptomatic stage [1]. With appropriate treatment, screening can result in disease prevention for those patients identified as at-risk. Early disease may be easier and less expensive to treat, which positions screening strategies as potentially sound investments for healthcare systems. Several countries have developed national screening programs that have led to increased disease detection rates and prevention [2, 3].

However, screening is not entirely risk-free and usually represents an immediate economic burden for systems with tight budget constraints. Some screening tools are associated with direct health risks (X-rays and radiation), and others might not provide a real additional value if, for instance, no follow-up treatment is available [1]. Additionally, tests need to be sufficiently reliable and accurate, since high proportions of false negatives or false positives might represent worse health outcomes and unnecessary diagnostic costs [4, 5]. To maximize value, an economic evaluation is a useful tool to compare the potential benefits, risks, and costs of different strategies and to inform resource allocation decisions. All health systems have scarce resources and are faced with opportunity costs; this means that any investment in a screening tool will come at the cost of other health services to the detriment of those patients who would have been treated [6].

Recognizing opportunity costs, healthcare systems may require that health interventions are both clinically and cost-effective to be considered for implementation [7]. Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) can be trial-based evaluations that use trial data to compare alternatives [8]; however, they are expensive to conduct and often require large sample sizes to obtain sufficient statistical power [9]. To overcome these challenges, model-based economic evaluations of screening tools have become a commonplace. Inputs are obtained from the best available sources and combined in mathematical models that replicate patient use of different strategies and provide a summary of costs and consequences for further analysis and comparison [10]. However, given that screening tools are used early in the treatment pathway, economic evaluations of screening strategies have many specific challenges to overcome. The objective of this study is to provide an overview of the different types of challenges and methodologies reported in the most recent cost-effectiveness analyses of screening strategies.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

A systematic review was conducted to identify the latest cost-effectiveness analyses (CEAs) of screening tools. Review and reporting followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [11]. Only research articles published in English and in 2017 were eligible for inclusion. CEAs comparing screening strategies versus no screening or other alternatives were included. There were no exclusion criteria based on the disease area. However, studies focusing on genomic screening and screening for blood transfusion, cost-benefit and cost-minimization studies, and review articles, editorial letters, news, study protocols, case reports, posters, and conference abstracts were excluded.

Searches and study selection

We searched the online databases of EMBASE and MEDLINE. Search terms included Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), Emtree, and keywords for “mass screening” or screening, economic evaluation, and cost-effectiveness analysis. The last search was run on August 17, 2017. The search strategies can be found in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2. Two independent authors (NI and ES) screened all titles and abstracts. Any reference included by either reviewers at this stage was included for full-text review. This section was conducted independently and in duplicate. Disagreements at this stage were settled by discussion until a consensus was reached by both authors (NI and ES).

Data extraction

We extracted the study characteristics and findings including the population, disease/condition, screening tools (strategies), comparators, perspective, time horizon, discounting, outcome or effectiveness measures (i.e., expected life years, quality-adjusted life years, cases detected), and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs). A description of the findings was portrayed in a narrative synthesis. Results were compared to an economic evaluation focused on the early diagnosis and treatment of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) that is currently being developed by the authors (NI and ES).

Results

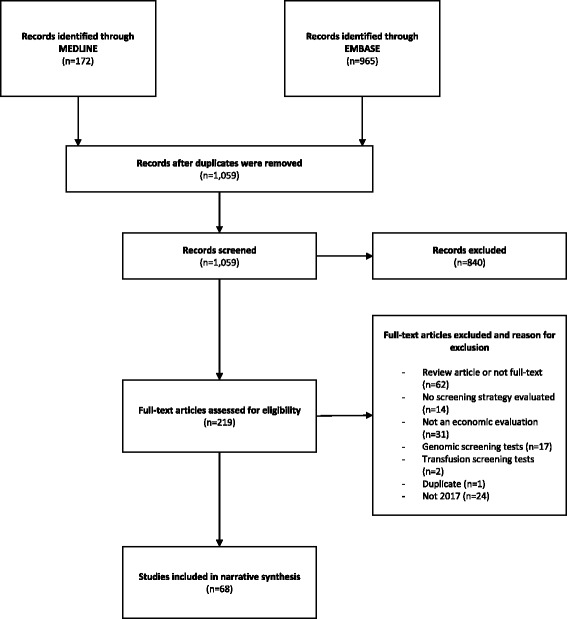

A total of 1059 records were found after 109 duplicates were removed. Two hundred nineteen articles were included for full-text assessment after 840 were excluded during the abstract screening stage (Fig. 1). Finally, 68 economic evaluations of screening tools were narratively synthesized (Table 1). A total of 26 studies (38.2%) evaluated the screening tools for cancer, 6 (8.8%) for hepatic disease, 5 (7.3%) for sexually transmitted disease, and 4 (5.8%) for heart disease. Twenty-nine (42.6%) added a “no screening” alternative for comparison. Thirty-five (51.4%) used quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) as the main outcome. Fifty-three studies (77.9%) modeled treatment options that followed screening and diagnostic testing. Finally, 7 studies (10.3%) concluded that the screening tool(s) they were evaluating were not cost-effective compared to current practice. The rest concluded that the implementation of screening tools had a high probability of being cost-effective. However, some specific recommendations regarding target populations, cost-effectiveness thresholds, and screening frequencies were made by some CEAs. Reported challenges and limitations of the economic evaluations were divided into three categories. The first one pertains to the screening pathway. It takes into account the test availability and sequencing, treatment options, accuracy, and patient compliance. The second describes the pre-symptomatic disease, prevalence, progression, and treatment effects. Finally, challenges with non-health benefits and spillovers are reported.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart. The PRISMA flow diagram details the search and study inclusion/exclusion process. It is a graphical representation of the flow of citations throughout the review

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Authors | Country | Disease | Screening tools (strategies) | Comparator | Population | Time horizon | Perspective | Discounting | Monetary units | Effectiveness outcome | ICER | Conclusion of base case | Funding | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albright et al. [55] | USA | Group B Streptococci | Universal screening with rectovaginal swab | No screening | Women with a prior cesarean delivery and a current singleton pregnancy planning to undergo a repeat cesarean | Lifetime | Healthcare | 3% | 2015 USD | Neonatal QALYs | Yes | Not CE | NA | Yes |

| Aronsson et al. [12] | Sweden | Colorectal cancer (CRC) | 1. Fecal immunochemical test (FIT) twice 2. Colonoscopy (once) 3. FIT every 2 years 4. Colonoscopy every 10 years |

No Screening | 60-year-old Swedish | Lifetime | Healthcare | 3% | EUR (no year) | QALYs | No | All strategies were CE vs no screening | SCREESCO study | Yes |

| Atkin et al. [18] | UK | Colorectal cancer | 13 different Sttrategies | Each other and “no colonoscopy” | Individuals with intermediate-grade adenomatous polyps | Lifetime | NHS | 4% | 2012–2013 GBP | QALYs, ELYs | Yes | 3-yearly ongoing colonoscopic surveillance without an age cut-off is CE | NIHR | Yes |

| Baggaley et al. [75] | UK | HIV | INSTI HIV1/HIV2 rapid antibody test | Not clear | Hackney Borough | 40 years | NHS | 4% | 2012 GBP | QALYs | Yes | Screening is CE | NHS, NIHR | Yes |

| Barzi et al. [19] | USA | Colorectal cancer | 13 screening tools: fecal occult blood test, Flex sig, colonoscopy, CT, DNA. | No screening | US population | 35 years | Societal | 3% | USD (no year) | Life years gained | No | Colonoscopy is CE | National Cancer Institute Core | Yes |

| Bleijenberg et al. [13] | Netherlands | Frailty | 1. Electronic frailty screening instrument (EFSI) 2. EFSI and nurse-led care program |

Usual care | Patients aged 60 or older | 1 year | Societal | 0% | 2012 EUR | QALYs | No | EFSI has high probability of being CE. The combination showed less value for money. | NA | Yes |

| Cadier et al. [66] | France and USA | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Biannual ultrasound + MRI + CT + biopsy | Real life | Patients with diagnosis of compensated cirrhosis | 10 years | Healthcare | 4% | 2015 (Unknown) | Life years gained | Yes | Biannual ultrasound (gold standard) screening is CE | No funding | Yes |

| Wrenn et al. [79] | USA | Incidental gallbladder carcinoma | Cholecystectomy | Not clear | Cholecystectomies performed between 06/2009 and 06/2014 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ELYs | No | Selective screening based on risk factors of specimen may be a more CE approach. | University of Vermont Medical Center Department of Surgery | Yes |

| Campos et al. [20] | 50 low- and middle-income countries | Cervical cancer | 1. Two-dose human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccination 2. One-time screening + treatment when neededz3. Cervical cancer treatment |

Each other | 1. 10-year-old girls2. 35-year-old women3. Women with cervical cancer | Lifetime | Payer | 3% | 2013 USD | DALYs | No | Both HPV vaccination and screening would be very CE | American Cancer Society | Yes |

| Chen et al. [45] | China | Hearing loss | Neonatal hearing screening | None | Newborns | 15 and 82 years | NA | 3% | 2012 RMB | 2012 RMB | No | Newborn hearing screening and intervention program in Shanghai is justified in terms of the resource input | National Natural Science Foundation of China | Yes |

| Cheng et al. [76] | China | Hepatitis E | 1. Screening (HEV antibody) and vaccination 2. Universal vaccination |

No vaccination | 60-year-old cohort | 16 years | Societal | 3% | 2016 USD | QALYs | Yes | Screening and vaccination is the most CE hepatitis E intervention strategy | Chinese National Natural Fund | Yes |

| Chevalier et al. [70] | France | Coronary artery disease | Maximal exercise test (ET) | None | Men aged > 35 years, with more than 2 h a week of training | NA | NA | NA | EUR (no year) | Cardiovascular disease cases | No | ET should be targeted at men with at least two cardiovascular risk factors | None | No |

| Chowers et al. [21] | Israel | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | Prenatal HIV screening | Current policy | Newborns | 100 years | Payer | 4% | NIS (no year) | QALYs | No | Universal prenatal HIV screening is projected to be cost saving in Israel | NA | Yes |

| Coyle et al. [22] | Canada | Cancer | Computed tomography (CT) scan + occult cancer screening | Cancer screening alone | Patients with unprovoked VTE | 12 months | Healthcare | 0% | CAD (no year) | QALYs and Missed cancer case | No | CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis for the screening of occult cancer is not CE | Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada | No |

| Cressman et al. [56] | Canada | Lung cancer | Low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) | Chest radiography | 60-year-olds | 30 years | Societal | 3% | 2015 CAD | QALYs | Yes | High-risk lung cancer screening with LDCT is likely to be considered CE | Terry Fox Research Institute | Yes |

| Crowson et al. [23] | USA | Vestibular schwannomas | Non-contrast screening Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) |

Full MRI protocol with contrast | Patients with asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss | NA | 3rd-party payer | NA | USD (no year) | Useful results (True positives and true negatives) | No | A screening MRI protocol is more CE than a full MRI with contrast | None | No |

| Devine et al. [24] | Thailand-Myanmar | Perinatal hepatitis B | 1. Hepatitis immunoglobulin (HBIG) after rapid diagnostic tests 2. HBIG after confirmatory test |

Vaccination alone | Refugee and migrant population on the Thailand-Myanmar border | From first contact to childbirth | Healthcare | NA | USD (no year) | Perinatal infection of Hepatitis B | Yes | HBIG following rapid diagnostic test is CE | Wellcome-Trust Major Overseas Programme in SE Asia | No |

| Devine et al. [46] | Thailand-Myanmar | Plasmodium vivax | G6PD testing | [1] chloroquine alone [2] primaquine without screeningz |

Refugee and migrant population on the Thailand-Myanmar border | 1 year | Healthcare | NA | 2014 USD | DALYs | Yes | G6PD RDTs to identify patients with G6PD deficiency before supervised primaquine is likely to provide significant health benefits | Welcome-Trust Major Overseas Programme in SE Asia | Yes |

| Ditkowsky et al. [25] | USA | Chlamydia trachomatis | Chlamydia screening | No Screening | Pregnant women aged 15–24 | 1 year | Healthcare | NA | 2015 USD | 2015 USD | No | Prenatal screening for C. trachomatis resulted in increased expenditure, with a significant reduction in morbidity to woman-infant pairs | None | Yes |

| Ethgen et al. [14] | France | Hepatitis C (HCV) | 1. IFN + RBV + PI for F2–F4 2. IFN-based DAAs for F2–F4 3. All-oral, IFN-free DAAs for F2–F4 4. All-oral, IFN-free DAAs for F0–F4 |

No intervention | French baby-boomer population (1945–1965 birth cohorts) | 20 years | Healthcare | 4% | EUR (no year) | QALYs, liver-related deaths | No | HCV screening and access to all-oral DAAs is CE | AbbVie | Yes |

| Ferguson et al. [69] | Canada | Chronic kidney disease (CKD) | CKD screening | Usual care | Rural Canadian indigenous populations | 45 years | Healthcare | 5% | 2013 CAD | QALYs | Yes | Targeted screening and treatment for CKD is CE | University of Manitoba, CIHR | Yes |

| Ferrandiz et al. [26] | Spain | Skin cancer | Clinical teleconsultations (CTC) | CTC + dermoscopic teleconsultation | Patients visiting 5 participating primary care centers because of concern over lesions suggestive of skin cancer | NA | NA | NA | EUR (no year) | Detected cases | No | Dermoscopic images improve the results of an internet-based skin cancer screening system | Health Council of the Regional Government of Andalusia-Spain | No |

| Goede et al. [27] | Canada | Colorectal cancer (CRC) | Fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) | Guaiac fecal occult blood testing and no screening | 40-year-old screening participants at average risk of CRC | Varied (20 to 45 years) | Healthcare | 3% | 2013 CAD | QALYs | Yes | FIT was the most CE strategy | Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care | Yes |

| Gray et al. [47] | UK | Breast cancer | 1. Risk 1 2. Risk 2 3. Masking 4. Risk 1 + masking |

No screening | Women eligible for a National Breast Screening Program (NBSP) | Lifetime | NHS | 4% | 2014 GBP | QALYs | Yes | Risk stratified NBSPs were relatively CE compared to the UK NBSP | FP7-HEALTH-2012-INNOVATION-1 | Yes |

| Gupta et al. [28] | USA | Cystic lung disease | High-resolution computed tomographic (HRCT) imaging | no HRCT screening | Patients with Spontaneous Pneumothorax | NA | Societal | 3% | 2014 USD | QALYs | Yes | HRCT image screening is CE | None | Yes |

| Haukaas et al. [44] | Norway | Tuberculosis (TB) | 1. TST + IGRA 2. IGRA 3. IGRA for risk |

No screening | Immigrants under 35 years of age from countries with a high incidence of TB | 10 years | Healthcare | 4% | 2013 EUR | Avoided TB cases | Yes | IGRA is the optimal algorithm at a threshold above €28,400 | None | No |

| Heidari et al. [29] | Iran | Hearing loss | 1. AABR 2. OAE |

Each other | Newborns | 1 year | Healthcare | NA | IRR (no year) | Detected cases | No | AABR is the CE alternative compared to OAE | I.R. Iran’s National Institute of Health Research | No |

| Horn et al. [30] | USA | Substance abuse | 1. Minimal screening 2. Screening, assessment and referral 3. 2 + brief intervention and follow-up |

Each other | Patients from emergency departments of 6 clinical sites across the US | 1 year | NA | NA | 2013 USD | 2013 USD | No | Resources could be better utilized supporting other health interventions. | NA | Yes |

| Htet et al. [71] | Myanmar | Pulmonary tuberculosis | Interventional model | Conventional model | Household contacts | 5 months | NA | NA | USD (no year) | Detected cases | Yes | The interventional model was more CE than the modified conventional model. | NA | No |

| Hunter et al. [31] | USA | Breast cancer | Digital breast tomosynthesis | Full-field digital mammography | Patients undergoing screening mammography | 1 year | NA | NA | 2014 USD | Cancer detected | No | DBT is a cost-equivalent or potentially CE alternative to FFDM | NA | No |

| John et al. [48] | India | Glaucoma | Community screening | No screening | people aged 40–69 years in urban areas in India | 10 years | Healthcare | 3% | 2015 INR | Additional treated cases, QALYs | Yes | A community screening program is likely to be CE | NZAID Commonwealth Scholarship | Yes |

| Keller et al. [68] | Australia | Prostate cancer | Serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) test every 2 years | Opportunistic screening | Australian male cohort aged between 50 and 69 years. | 20 years | Healthcare | 5% | 2015 AUD | QALYs | Yes | PSA-based screening is not CE | University of Queensland | Yes |

| Kievit et al. [32] | Netherlands | Cardiovascular (CV) disease | CV risk profiling | No screening | Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) | 10 years | Medical | 4% for costs and 1.5% for outcomes | EUR (no year) | QALYs | No | Screening for CV events in RA patients was estimated to be CE | NA | Yes |

| Kim et al. [49] | South Korea | Hepatitis C | One-time screening | No screening | People aged 40–70 | 5 years | Healthcare | 5% | USD (no year) | QALYs | Yes | HCV screening and treatment is likely to be highly CE | Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharmaceuticals | Yes |

| Kim et al. [63] | USA | Human Papillomavirus | 1. Cytology 2. HPV test 3. Co-test |

Each other | US women | 10–44 years | Societal | 3% | USD (no year) | QALYs | No | Screening can be modified to start at later ages and at lower frequencies | National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health | No |

| Lapointe-Shaw et al. [72] | USA | Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae | Rectal swab screening | No screening | 65-year-old patients admitted to a general medical inpatient service. | 19.2 years | US Hospital | 3% | 2016 USD | QALYs | Yes | Screening inpatients for CPE carriage is likely CE | None | No |

| Lew et al. [58] | Australia | Colorectal cancer | Projected iFOBT screening | No screening | People aged 50–74 | 24 years | Health services | 5% | 2015 AUD | Life years gained | No | The program is highly CE | Cancer Institute NSW and Cancer Council NSW | Yes |

| Liow et al. [77] | USA | Bone malignancies | Routine femoral head histopathology | None | Patients that underwent primary total hip arthroplasty | 4 years | NA | NA | 2016 USD | QALYs | Yes | Routine femoral head histopathology may be CE | NA | Yes |

| Mo et al. [15] | China | Cervical cancer | 1. Liquid-based cytology test + HPV DNA test 2. Pap smear cytology test + HPV DNA test 3. Visual inspection with acetic acid |

No intervention | Adolescent girls (Above 12 years old) | Lifetime | Societal | 3% | 2015 USD | QALYs | Yes | The HPV4/9 vaccine with current screening strategies was highly CE | Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences | Yes |

| Morton et al. [50] | UK | Breast cancer | Mammography | No screening | Females over 45 years old | 20 years | NHS | 4% | 2016 GBP | QALYs | Yes | Calculations suggested that breast cancer screening is CE | NA | Yes |

| Mullie et al. [51] | Canada and USA | Latent tuberculosis | 1. Tuberculin skin test 2. QuantiFERON®-TB-Gold In-Tube |

Each other | Healthcare workers | 20 years | Healthcare | 3% | 2015 CAD | QALYs | Yes | Annual tuberculosis screening appears poorly CE | McGill University, CIHR | Yes |

| Petry et al. [16] | Germany | Human papillomavirus | 1. HPV test followed by Pap cytology 2. HPV test followed by cytology 3. HPV test followed by colposcopy 4. Co-testing with HPV and Pap |

Pap cytology | Women aged 30–65 | 10 years | NA | 3% | EUR (no year) | Avoided deaths | No | The greatest clinical impact was achieved with primary HPV screening (with genotyping) followed by colposcopy | Hoffmann-La Roche | Yes |

| Phisalprapa et al. [33] | Thailand | Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | Ultrasonography screening | No screening | 50-year-old metabolic syndrome patients | Lifetime | Societal | 3% | 2014 USD | QALYs | Yes | Ultrasonography screening for NAFLD with intensive weight reduction program is CE | NA | Yes |

| Pil et al. [59] | Belgium | Skin Cancer | Total body skin examination (TBSE) | Lesion-directed screening | Belgian population over 18 years of age | 50 years | Societal | Outcomes at 1.5% and costs at 3% | EUR (no year) | QALYs | Yes | 1-time TBSE is the most CE strategy | The LEO Foundation and the Belgian Federation Against Cancer | Yes |

| Prusa et al. [80] | Austria | Toxoplasmosis | Prenatal screening | No screening | Birth cohorts from 1992 to 2008 and | 20 years | Societal | 3% | 2012 Euro | Life and productivity loss | No | Cost savings of prenatal screening for toxoplasmosis and treatment are outstanding | None | Yes |

| Requena-Mendez et al. [34] | All Europe | Chagas disease | T. cruzi serological screening | No screening | Latin American adults living in Europe | Lifetime | Healthcare | 3% | EUR (no year) | QALYs | YES | Screening for Chagas disease in asymptomatic Latin American adults living in Europe is a CE strategy. | European Commission 7th Framework Program | Yes |

| Roberts et al. [60] | Australia | Rheumatic heart disease | Echocardiographic screening | Screening every other year and no screening | Indigenous Australian Children | 40 years | Healthcare | 5% | 2013 AUD | DALYs, heart failure, surgery | Yes | Echocardiographic screening is CE assuming that RHD can be detected ≥ 2 years earlier by screening | University of Western Australia | Yes |

| Rodriguez-Perez et al. [64] | Spain | Type 2 diabetes | DIABSCORE | HbA1c or blood glucose | Adult primary care patients in Spain | NA | NA | NA | EUR (no year) | Cases detected | No | DIABSCORE is a CE and valid method for opportunistic screening of type 2 diabetes | Carlos III Health Institute | No |

| Saito et al. [35] | Japan | Gastric cancer | ABC method: HPA and measuring serum PG concentrations | Annual endoscopic screening | 50-year-old Japanese individuals who have high gastric cancer incidence and mortality who had not undergone H. pylori eradication | 30 years | Healthcare | 2% | 2014 USD | Lives saved and QALYs | Yes | ABC method cost less and saved more lives | Niigata University of Health and Welfare | Yes |

| Schiller-Fruehwirth et al. [36] | Austria | Breast cancer | 1. Organized screening 2. Opportunistic screening |

No screening | 40-year-old asymptomatic women | Lifetime | Healthcare | 3% | 2012 EUR | Life years gained | Yes | The decision to adopt organized screening is likely an efficient use of limited health care resources in Austria | Main Association of Social Security Institutions | Yes |

| Selvapatt et al. [65] | UK | Hepatitis C | HCV testing | No screening | All persons attending a London DTU | Lifetime | Healthcare | 4% | 2013 GBP | ELYs, QALYs | Yes | Concludes cost effectiveness of outreach testing and treatment of hepatitis | Biomedical Research Council to Imperial College Department of Hepatology | Yes |

| Sharma et al. [61] | Lebanon | Cervical cancer | 1. Cytology 2. HPV DNA screen |

No screening | Women aged 25–65 years | NA | Societal | 3% | I$ (no year) | Years of life saved | Yes | Increasing coverage to 50% with extended screening intervals provides greater health benefits | None | Yes |

| Smit et al. [73] | Belgium | Tuberculosis | X-ray screening | No screening | Risk groups: prisoners, youth in detention centers, undocumented migrants | 1 year | Flemish Agency for Care and Health | 0% | 2013–14 EUR | Detected cases | No | Tuberculosis screening is relatively expensive | Flemish Agency for Care and Health | No |

| Ten Haaf et al. [52] | Canada | Lung cancer | Computer tomography | No screening | Persons born between 1940 and 1969 | Lifetime | Healthcare | 3% | 2015 CAD | Life years gained, false positive screen | Yes | Lung cancer screening with stringent smoking eligibility criteria can be CE | Clinical Evaluative Sciences | Yes |

| Teng et al. [62] | New Zealand | Helicobacter pylori infection, gastric cancer | 1. Fecal antigen 2. Serology |

Current practice | Total population and targeted Māori (25–69 years old) | Lifetime | Healthcare | 3% | 2011 USD | QALYs | Yes | Screening was likely to be CE particularly for indigenous populations | Health Research Council of New Zealand | Yes |

| Tjalma et al. [37] | Belgium | Cervical cancer | Dual stain cytology | Cytology | Women between 25 and 65 years of age | 60 years | Healthcare | NA | EUR (no year) | QALYs | Yes | Diagnostic cytology benefits all stakeholders involved in cervical cancer screening | NA | Yes |

| Tufail et al. [38] | UK | Diabetic retinopathy | Automated diabetic retinopathy image assessment systems (ARIAS) | Human graders | Patients with a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus who attended their annual visit at the diabetes eye-screening program | NA | NHS | 4% | 2013–2014 GBP | Appropriate screening outcome | No | ARIAS have the potential to reduce costs and to aid delivery of DR screening | Novartis | No |

| Meulen et al. [39] | Netherlands | Colorectal cancer (CRC) | 1. Fecal immunology test 2. gFOBT 3. Sigmoidoscopy |

Each other | Screening-naive subjects ages 50 to 74 years, living in the southwest of the Netherlands | Lifetime | Healthcare | 3% | 2012 EUR | Positivity rates, detection of adenoma and CRC, QALYs | Yes | Screening stratified by gender is not more CE than uniform FIT screening | NA | Yes |

| van Katwyk et al. [53] | Canada | Diabetic retinopathy | Extended coverage of diabetic eye examination | Usual care | Prince Edward Island residents over 45 years of age who had diabetes | 30 years | Healthcare | 5% | 2015 CAD | QALYs | Yes | Extending public health coverage to eye examinations by optometrists is CE | CIHR | Yes |

| van Luijt et al. [67] | Norway | Breast cancer | Mammography | No screening | Norway female population | Lifetime | Societal | 4% | 2014 NOK | QALYs | No | The NBCSP is a highly CE measure to reduce breast cancer specific mortality | Research Council Norway | Yes |

| Wang et al. [17] | China | Chronic kidney disease | 1. Day 1 2. Random 3. Day 1 + random 4. Day 1+ random + day 2 |

Each other | Outpatients admitted to Peking University First Hospital from January 2013 to January 2014 | 30 years | Societal | 5% | CNY (no year) | QALYs | Yes | Combining two first morning urine samples and one randomized spot urine sample is CE | National Key Technology R&D Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology | Yes |

| Welton et al. [40] | England and Wales | Atrial fibrillation | 1. Single systematic population screen 2. Single systematic opportunistic screen |

No screening | General population in England and Wales | Lifetime | NHS | 4% | 2015 GBP | QALYs | Yes | Population-based screening is likely to be CE | NIHR | Yes |

| Whittington et al. [74] | USA | Staphylococcus aureus infection | 1. Universal decolonization 2. Targeted decolonization 3. Screening and isolation |

Each other | Hypothetical cohort of adults admitted to the Intensive care unit. | 1 year | Hospital | NA | 2015 USD | QALYs | Yes | This study supports updating the standard practice to a decolonization approach. | NA | No |

| Williams et al. [41] | USA | Prosthetic joint infection | 1. 4 swabs decolonization 2. 2 swabs 3. Nasal swab alone |

No screening and decolonization | Hip and knee replacement patients | NA | Societal | NA | 2016 USD | Cases of prosthetic joint infections | No | The 2-swab and universal-decolonization strategy were most CE | None | Yes |

| Yang et al. [54] | Taiwan | Lung cancer | 1. Computed tomography (CT) 2. Radiography |

No screening | Smokers between 55 and 75 years of age | Lifetime | Healthcare | 3% | 2013 USD | QALYs | Yes | Low-dose CT screening for lung cancer among high-risk smokers would be CE in Taiwan | Ministry of Science and Technology, and the National Cheng Kung University Hospital | Yes |

| Yarnoff et al. [42] | USA | Chronic kidney disease (CKD) | CKD risk scores | No screening | US population | Lifetime | Healthcare | 3% | 2010 USD | QALYs | Yes | CKD risk scores may allow clinicians to cost-effectively identify a broader population for CKD screening | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | Yes |

| Yoshimura et al. [78] | Japan | Osteoporosis | Screening and alendronate therapy | No screening and no therapy | Postmenopausal women over 60 years | 5 years | Healthcare | 3% | USD (no year) | QALYs | Yes | Screening and treatment would be CE for Japanese women over 60 years. | Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology | Yes |

| Zimmermann et al. [43] | Kenya | Cervical cancer | 1. Visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) 2. Papanicolaou smear 3. Testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) |

Cryotherapy without screening | Hypothetical cohort of 38-year-old women | Lifetime | Societal | 3% | 2014 USD | ELYs | No | VIA was most CE unless HPV could be reduced to a single visit | NA | Yes |

QALYs quality-adjusted life years, ELYs expected life years, RMB Renminbi, USD United States dollar, CAD Canadian dollar, AUD Australian dollar, EUR euro; GBP British pound, NIS Israeli new shekel, IRR Iranian rial, CNY Chinese yuan, INR Indian rupee, NOK Norwegian krone, CE cost-effective, NA not applicable

Screening pathway

The value of the screening test is dependent on the full screening pathway. This refers to the screening test and the subsequent follow-up undertaken because of the results of the screening. The review identified multiple studies that evaluated different screening pathways by modifying the order in which screening tests were administered [12–17]. This allowed investigators to determine trade-offs between potential screening sequences. However, these models are dependent on data availability, and lots of different types of evidence are necessary to inform the screening pathway including screening and diagnostic test accuracy and screening compliance. Most studies explored challenges such as conditional test accuracy, a lack of a diagnostic gold standard, outcomes of false positives and false negatives, or screening compliance.

Accuracy

Twenty-five studies (36.7%) explicitly reported challenges regarding screening test accuracy [18–43]. One common challenge was the lack of data on test accuracy. In some cases, authors had to assume the accuracy of the screening test [28, 30, 32, 33]; more commonly, it was assumed that tests had the same performance regardless of prior testing [19, 34]. This assumption is particularly important when different sequences of screening and diagnostics tests are being evaluated. Accuracy assumptions were often tested using different combinations of sensitivity and specificity. Barzi et al. modeled a hypothetical test and, through model iterations, determined the combination of test sensitivity and specificity that would yield optimal results in terms of cost-effectiveness [19]. Crowson et al. undertook a two-way sensitivity analysis of sensitivity and specificity to determine their importance to health outcomes and costs [23]. Sensitivity analyses are useful tools to evaluate the uncertainty around test accuracy estimates. These analyses allow a threshold to be determined at which a specific screening tool would result in a cost-effective strategy.

To understand the implications of screening on patients’ health, it is important to model the outcomes of any follow-up diagnostic tests. However, one common difficulty is that there is usually no information on the accuracy of the diagnostic test in the screen-positive population. A few assumptions were made to account for this uncertainty. A study in Thailand for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease used pooled estimates of diagnostic accuracy from a meta-analysis assuming independence between the screening and diagnostic accuracy [33]. Chowers et al. tested different accuracy rates for HIV diagnostic tests with sensitivity analyses [21]. Other studies assumed specific accuracy estimates (usually 100%) and acknowledged the limitations, such as potentially overestimating cost-effectiveness estimates by excluding pertinent costs associated to misclassified patients [22, 29, 44].

False positive and negative outcomes

Screening and diagnostic accuracy determines the proportion of patients who will continue to receive treatment or further follow-up. It is important to understand the health outcomes of all patients screened. Patients identified as false positive or false negative are particularly difficult to consider in cost-effectiveness analysis given the lack of data on these patients. Costs and outcomes for patients who followed incorrect screening and treatment pathways were included in 22 (32.3%) of the studies [12, 17, 18, 21, 23–25, 29, 36, 40, 42, 43, 45–54]. Even though some cost-effectiveness analyses identified false positives in the screening pathways, one alternative was to assume 100% accurate diagnostic tests; this meant patients identified incorrectly during screening would never go on to inappropriate treatment [29, 42, 49]. In these cases, there were extra diagnostic costs, but no treatment-specific costs or outcomes were pertinent. Health outcomes may be overestimated when assuming 100% accurate diagnostic tests. Alternatively, some studies assumed that diagnostic tests were not perfect and included costs and health consequences of the incorrect treatment of false positive patients, such as healthy patients receiving unnecessary treatment and having side effects [17, 43, 48, 53, 54]. Whenever a treatment poses a considerable threat to false positives (or a considerable monetary cost), CEAs should acknowledge and include these scenarios. When false negative patients were modeled, it was assumed that they would progress at the same rate as untreated patients and were usually identified as being sick once symptoms appear [17, 21, 45, 46, 48]. This is comparable to the pathway for all sick patients under a “no screening” arm. A high proportion of false negatives (i.e., tests with low sensitivity) will translate to fewer identified sick patients. Depending on the disease, tests, costs, and health outcomes, a CEA could evaluate whether repeated testing is worth implementing to reduce this proportion of patients. Four studies failed to model false positives and/or negatives after acknowledging their potential effect to the evaluation [12, 18, 25, 36].

Compliance

Screening pathways are greatly altered by different rates of participation and compliance. Screening is only effective if the target population and healthcare providers are engaged. Twenty-nine evaluations (42.6%) identified patient participation and compliance as an important model parameter [12, 14, 16–20, 25, 27, 28, 32, 36, 37, 43–46, 48–51, 55–62]. Morton et al. reported that the results of a national breast cancer screening program in the UK would be impacted by the proportion of the at-risk population who decided to participate [50]. Lower compliance translates to lower screening and diagnostic costs, but also represents a higher burden of disease if non-compliers are diagnosed at later and more expensive-to-treat stages of disease. Screening can also raise costs without improving health outcomes if identified patients fail to follow further recommended treatment due to unreliable testing. John et al. also modeled non-compliers who had a chance of getting sick and being identified by opportunistic screening [48]. Additionally, studies such as that conducted by Aronsson et al. explain how compliance rates are dependent on the screening tool to be evaluated [12, 19]. They model colonoscopy and fecal immunochemical tests (FIT) to screen for colorectal cancer, and take into account the different compliance rates for each alternative. Since colonoscopy is expected to make people more uncomfortable than the FIT, less people are expected to comply with the former [12, 19]. To test this, willingness-to-pay to avoid colonoscopy was estimated [12]. However, information about the compliance rates for different screening tests was rarely available. Ten studies (14.7%) assumed a 100% compliance rate [17, 25, 27, 28, 32, 45, 51, 55, 57, 59, 63]. The effect of this assumption over cost-effectiveness estimates depends on the specific evaluation being conducted, specifically the trade-off between lower screening costs and worse health outcomes due to unidentified disease.

Pre-symptomatic disease

Disease prognosis and patient evolution from pre-symptomatic stages of disease were modeled in most cases to estimate aggregate costs and outcomes. All included studies but 2 (3%) [38, 64] explicitly commented on challenges encountered while trying to adequately model disease progression and patient transition through health states. Pre-symptomatic disease refers to the point in progression when the disease is developing but no symptoms are apparent. This is the point when screening tools are useful but usually when there is very little data about progression of the disease. Once identified as having a disease, more data is available for modeling cost-effectiveness.

Prevalence/incidence

Screening models often focus on at-risk populations. Incidence rates are used to determine the proportion of patients who enter the models at pre-symptomatic stages. This is useful for scenarios with repeated screening procedures, as a dynamic model can be developed to evaluate repeated screening processes while taking into account new at-risk patients [47]. On the other hand, some studies included population-specific incidence rates [19, 35, 47]. A different approach consists on evaluating one-time-only screening procedures targeting prevalent disease [49]. Deciding between repeated versus one-time testing depends on the type of disease and population of the evaluation. A one-time test for tuberculosis might be appropriate for immigrant populations, while testing for lung cancer among smokers is recommended to be carried out repeatedly. The sequence and frequency of tests can be tested through modeling to determine the cost-effective option. Sensitivity analyses determined that cost-effectiveness estimates were highly sensitive to changes in prevalence and incidence estimates [25, 49, 65]. Testing for a rare disease might not result cost-effective compared to a common disease given a similar health and economic burden.

Pre-symptomatic disease progression

Once an at-risk population is identified, some cost-effectiveness analyses focused on modeling the pre-symptomatic stages of disease. There is a time interval before clinical symptoms appear and after disease onset where disease is identifiable by screening tools. This timeframe, also called sojourn time, is a major challenge for CEA since progression of pre-symptomatic disease if often unknown (Table 2). Uncertainty around sojourn time was tested by 3 studies (4.4%) [36, 60, 66]. van Luijt et al. determined a fixed preclinical stage of breast cancer where disease could be identified by screening [67]. This study also allowed for disease regression or progression to more advanced pre-symptomatic stages. Atkin et al. modeled similar pre-symptomatic stages for colorectal cancer and adenoma [18]. Sensitivity analyses allowed to estimate the effect of varying the interval for sojourn time on cost-effectiveness. These studies concluded that longer sojourn time represented improved disease identification rates.

Table 2.

Summary of methodological issues and suggestions to develop CEAs of screening tools

| Issues | Suggestions |

|---|---|

| Screening/diagnostic test accuracy | Model iterations with two-way sensitivity analyses using different combinations of sensitivity and specificity to determine a threshold at which screening becomes cost-effective. Assuming 100% accuracy might overestimate cost-effectiveness estimates. |

| Modeling false positive and negative results | Building a pathway for false positives and false negatives that includes their costs and health outcomes. For false positives, it is important to include costs and health outcomes associated to unnecessary diagnostics and treatment. For false negatives, it is important to include the costs and health outcomes of a delayed diagnosis. |

| Compliance rates | Model the compliance rate of patients and healthcare delivery professionals. Compliance rates are particularly important when repeated screening is being recommended, since low compliance may mean that the costs of early testing are wasted if further testing is not done. |

| Prevalence/incidence | Screening programs are usually conducted repeatedly over time. Dynamic models (incidence based) can be developed to evaluate repeated screening processes while considering new at-risk patients. One-time-only screening procedures only take into account prevalent disease. |

| Pre-symptomatic progression rates | Population-specific progression rates are often difficult to find for pre-symptomatic disease. Extrapolation from the clinical phase, or from similar conditions, could represent a first step to tackle the uncertainty around these parameters. Sensitivity analyses should determine how progression rates are expected to affect cost-effectiveness estimates. |

| Sojourn time | Sojourn time determines when screening is appropriate. This is a crucial input into a screening model and there is rarely evidence to estimate it. Creating various scenarios with different sojourn times may allow the investigators to estimate its impact on cost-effectiveness estimates. Different sojourn times will affect the cost-effectiveness of different test frequencies and should be evaluated using cost-effectiveness modeling. |

| Treatment and health outcomes | CEAs of screening tools should always include follow-up diagnostic and treatment. Quality-adjusted life years are appropriate to account for health outcomes, but these should be specific to the population being evaluated. Every potential health outcome needs to be accounted for including side effects of screening and/or diagnostic tests. |

| Non-health-related spillovers | Evaluating a screening tool from a societal perspective requires the inclusion of all non-health costs and outcomes. It is important to understand the trade-offs between the different types of costs and benefits. The inclusion of non-health costs and outcomes has important distributional assumptions and will value patients differently. |

Modeling patient progression during the sojourn time, i.e., through pre-symptomatic health states, remains a challenge. Three studies extrapolated progression rates from symptomatic disease stages to pre-symptomatic disease [18, 56, 68]. In some cases, fast progressing disease may cause death before diagnosis. Death rates for pre-symptomatic disease were available for colorectal cancer using Kaplan-Meier estimators from lifetime data [18], health state-specific mortality risks in chronic kidney disease [69], and gastric cancer [62]. Additionally, based on differential progression rates and life expectancy, two studies evaluated the potential effect of lead time bias in their studies [35, 54]. This bias explains how early diagnosed patients might not experience an increase in expected survival, but instead spend longer periods under treatment. This effect gives the illusion of higher survival expectancy [35], resulting in biased cost-effectiveness estimates. Survival has a major impact over health-related outcomes in CEAs, and assuming a higher rate will overestimate the health benefits. This is one example of a model input that is likely to affect the cost-effectiveness of a screening tool and should be tested in sensitivity analyses. Yang et al. used population matching (cancer cases vs general population) and a difference in difference methodology to determine if early diagnosis provided improved life expectancy [54]. Both studies showed differential survival rates favoring patients who were diagnosed early after accounting for potential lead time bias [35, 54].

Treatment effect and health outcomes

According to the WHO, screening interventions are expected to provide treatment alternatives for those patients with identified cases of disease [1]. However, 15 studies (22%) failed to model a treatment pathway [22–24, 26, 29, 31, 38, 44, 57, 64, 70–74]. The main outcomes captured by these studies were the following: cases detected, missed cases, avoided cases, and identified true positives and true negatives. Decision trees were most commonly used for these modeling tasks. However, these models are insufficient for making reimbursement decisions, since efficacious interventions or therapies are required to follow screening and diagnostic procedures to improve patients’ health. Without these benefits, screening procedures are not capturing all consequences, leading to incomplete CEAs. On the other hand, studies that modeled treatment pathways captured different health outcomes to evaluate cost-effectiveness of screening strategies. Quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) were estimated by 39 studies (57.3%) [12–15, 17, 18, 21, 27, 28, 32–35, 37, 39, 40, 42, 45–51, 53–57, 59, 62, 65, 67–69, 72, 74–78], and expected life years (ELYs) by 10 (14.7%) [18, 19, 36, 43, 52, 58, 65, 66, 79, 80]. Utilities were widely used, and the following challenges and methodologies were reported: Chowers et al. acknowledged having underestimated QALY outcomes in their prenatal HIV screening evaluation by excluding maternal utility measures. Additionally, treatment for false positives and its repercussions were excluded, even though treatment for healthy newborns is expected to cause disutility [21]. Ferguson et al. observed there was a difficulty assigning utilities for patients with undiagnosed chronic kidney disease. Therefore, they assumed similar utilities for undiagnosed and diagnosed cases [69]. Cheng et al. extrapolated already estimated utility weights for pre-symptomatic hepatitis A to model the preclinical stage of hepatitis E [76]. Assumptions around utility estimates are common, but require careful consideration to avoid a deviation from the initial target population. Although health outcomes are most often captured after treatment begins, some models included screening and diagnostic specific health effects. Risk of perforation due to colonoscopy was included by Atkin et al. in their colorectal cancer CEA [18]. Yang et al. included radiation-induced cancer cases from radiography screening [54]. Failing to include potentially negative health effects of screening tests will overestimate the health benefits and potentially underestimate associated costs.

Some studies reported uncertainty around treatment efficacy inputs [15, 44, 65, 66, 75]. Sensitivity and scenario analyses were broadly used to account for this uncertainty. Not surprisingly, cost-effectiveness estimates were influenced by treatment efficacy of early treatment and uptake [65, 66, 75]. A few studies conducted a value of information analyses to estimate the value of collecting further information to resolve decision uncertainty [18, 44, 75].

Non-health costs and outcomes, and spillovers

CEAs take into account the costs and outcomes of specific interventions and compare them to determine if they provide enough benefits relative to the cost compared to the next best alternative. However, not all potential benefits and costs are necessarily health related. The perspective of a CEA determines what kind of effects and costs will be included. A healthcare perspective seeks to compare costs and consequences that directly pertain to the healthcare sector. They generally focus on health-related outcomes [81]. Alternatively, a societal perspective attempts to capture all relevant costs and outcomes, health-related or not. Transportation costs, out-of-pocket expenses, and productivity losses are a few examples. These analyses evaluate the trade-off between health and any other outcome, but this information is rarely known, i.e., societal preferences between health and productivity or educational benefits [81]. This review identified 38 (55.8%) and 15 (22%) studies that developed their analyses under a healthcare [12, 14, 18, 20–23, 25, 27, 29, 34–40, 42, 44, 46–55, 58, 60, 62, 65, 66, 68, 69, 75, 78] and societal perspective [13, 15, 17, 19, 28, 33, 41, 43, 56, 57, 59, 61, 67, 76, 80], respectively. The following were specific studies that included non-health costs and/or outcomes: Cressman et al. estimated the productivity loss of lung cancer patients who had been previously working before starting treatment [56]. Phisalprapa et al. included non-medical costs (transportation, meals, accommodations, and facilities) in their evaluation of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [33]. Pil et al. used a patient questionnaire to assess indirect costs in their skin cancer screening CEA related to productivity loss, morbidity, and early mortality [59]. Sharma et al. included patient transportation costs [61]. The decision to include indirect (or non-medical) costs and outcomes depends on the decision maker’s perspective. The societal perspective allows a thorough analysis by including a broader spectrum of the associated consequences. However, including all indirect outcomes or externalities might prove a difficult task, and missing important outcomes will render the evaluation incomplete and possibly biased. It is also true that although most studies considering a societal perspective focused on costs, there was one that also included non-health benefits or outcomes. Chen et al. compared the benefits of the different types of education that children received after being screened and treated for neonatal hearing loss. Children who were successfully identified and treated for hearing loss were expected to have better educational outcomes [45]. Sensitivity analyses determined that cost-effectiveness estimates were most affected by the inclusion of the societal costs [80].

One concern of adopting a societal perspective is the implicit assumptions on how resources should be distributed; for example, including productivity costs (an important part of non-health outcomes) generally benefits treatments of the working age population at the cost of children and seniors [82]. Prusa et al. developed a CEA of toxoplasmosis screening for children in Austria. Besides considering the projected lifetime productivity loss of the affected children, they also considered the productivity loss of parents [80]. Consequences (health-related or not) that fall on third or external parties are called spillover effects [83]. Spillover effects were not identified or modeled in any other study. Basu and Meltzer argue that CEAs might better reflect all associated costs and outcomes by considering spillovers [83]. CEAs that focus on screening tools have specific challenges to address regarding spillovers or externalities, especially health-related ones. False positive tests for venereal diseases, for instance, can have negative consequences for families and third parties in terms of anxiety, stress, and divorce. On the other hand, there are potential positive spillovers. For example, screening tests might have a modest capacity to identify similar conditions. This review did not identify studies that included benefits of such opportunistic identification.

Discussion

This study reviewed the latest CEAs of screening tools and provided a thorough breakdown of challenges and suggestions to overcome them. The included studies mentioned several assumptions and methodological alternatives that were grouped in four major categories: the screening pathway, pre-symptomatic disease, treatment outcomes, and spillovers and externalities. To capture all important costs and outcomes of a screening tool, screening pathways should be modeled through the treatment of the patient. Also, false positive and false negative patients are likely to have important costs and benefits and should be included in the analysis. As these patients are difficult to identify in regular data sources, common treatment patterns should be used to determine how these patients are likely to be treated. Many assumptions are needed when modeling screening tools. It is important that these assumptions are clearly indicated and that the consequences of these assumptions are tested in sensitivity analyses. These include the assumptions such as the independence of consecutive tests and the level of patient and provider compliance to guidelines and sojourn times, i.e., the time between when a patient can be identified by screening test and when they would have been identified due to symptoms. As data is rarely available regarding the progression of undiagnosed patients, extrapolation from diagnosed patients may be necessary. Not surprisingly, different scenarios concluded that longer sojourn times were likely to result in improved health outcomes. This becomes one of the main drivers of the effectiveness of a screening test, besides the accuracy at which it identifies patients correctly. This was particularly true when available treatment was capable of modifying disease progression. Finally, non-health costs and outcomes were observed for studies that developed their analyses under a societal perspective. These were not consistently reported, mostly likely due to different guidelines from decision makers.

This review thoroughly examined the latest methodological challenges associated with modeling CEAs of screening tools. However, some limitations are to be noted. Studies focusing on genomic and blood transfusion screening tests were excluded. Genomic screening was excluded because a recent paper evaluated CEAs of genomic screening tests [84]. Blood transfusion tests were excluded because different issues arise when testing blood for treatment rather than testing patients for disease [85]. Challenges and methodologies of CEAs are expected to vary considerably between these groups. Finally, studies were limited to 2017 to capture the most recent state of the art in this area. We were interested in the latest available evidence to appropriately review the most up-to-date methodologies for modeling screening tools from a health economic perspective. However, all diseases were included to avoid disease-specific issues and to provide a broad learning across disease areas.

Conclusion

Many new screening tools are being developed and require cost-effectiveness analyses to support their value proposition. Screening tools should follow diagnostic guidelines, but have additional challenges given that sojourn times and pre-symptomatic progression data is rarely known. Current cost-effectiveness analyses extrapolate pre-symptomatic progression from symptomatic patients and thoroughly test assumptions in sensitivity analyses, including sojourn times. By following these methodological suggestions, screening tool evaluations are expected to become a better reflection of medical practice and to provide better quality evidence for decision makers making difficult trade-offs between funding screening interventions or other health technologies.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Authors’ contributions

Both authors contributed to (i) the conception of the review, (ii) data extraction and analysis, and (iii) manuscript drafting and revising. The authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of this work. Both authors approve this version to be published.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Table 3.

EMBASE search strategy

| 1 | exp mass screening/ |

| 2 | limit 1 to (human and english language) |

| 3 | screen*.mp. |

| 4 | limit 3 to (human and english language) |

| 5 | exp “cost benefit analysis”/ or exp “cost effectiveness analysis”/ or cost-effective*.mp. |

| 6 | limit 5 to (human and english language) |

| 7 | 2 or 4 |

| 8 | 6 and 7 |

Appendix 2

Table 4.

MEDLINE search strategy

| 1 | exp Mass Screening/ |

| 2 | limit 1 to (english language and humans) |

| 3 | screen*.mp. |

| 4 | limit 3 to (english language and humans) |

| 5 | exp Cost-Benefit Analysis/ or cost-effective*.mp |

| 6 | limit 5 to (english language and humans) |

| 7 | economic evaluation.mp. |

| 8 | limit 7 to (english language and humans) |

| 9 | 2 or 4 |

| 12 | 6 or 8 |

| 11 | 9 and 10 |

References

- 1.Wilson JM, Jungner YG. Principles and practice of mass screening for disease. Bol Oficina Sanit Panam. 1968;65(4):281–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanks RG, Wallis MG, Moss SM. A comparison of cancer detection rates achieved by breast cancer screening programmes by number of readers, for one and two view mammography: results from the UK National Health Service breast screening programme. J Med Screen. 1998;5(4):195–201. doi: 10.1136/jms.5.4.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Velzen CL, Clur SA, Rijlaarsdam ME, Bax CJ, Pajkrt E, Heymans MW, et al. Prenatal detection of congenital heart disease—results of a national screening programme. BJOG. 2016;123(3):400–407. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petticrew MP, Sowden AJ, Lister-Sharp D, Wright K. False-negative results in screening programmes: systematic review of impact and implications. Health Technol Assess. 2000;4(5):1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tosteson AN, Fryback DG, Hammond CS, Hanna LG, Grove MR, Brown M, et al. Consequences of false-positive screening mammograms. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(6):954–961. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drummond M, Weatherly H, Ferguson B. Economic evaluation of health interventions. BMJ. 2008;337:a1204. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCabe C, Claxton K, Culyer AJ. The NICE cost-effectiveness threshold: what it is and what that means. PharmacoEconomics. 2008;26(9):733–744. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826090-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Dongen JM, van Wier MF, Tompa E, Bongers PM, van der Beek AJ, van Tulder MW, et al. Trial-based economic evaluations in occupational health: principles, methods, and recommendations. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(6):563–572. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brennan A, Akehurst R. Modelling in health economic evaluation. What is its place? What is its value? PharmacoEconomics. 2000;17(5):445–459. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200017050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinstein MC, O'Brien B, Hornberger J, Jackson J, Johannesson M, McCabe C, et al. Principles of good practice for decision analytic modeling in health-care evaluation: report of the ISPOR Task Force on Good Research Practices—modeling studies. Value Health. 2003;6(1):9–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2003.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aronsson M, Carlsson P, Levin LA, Hager J, Hultcrantz R. Cost-effectiveness of high-sensitivity faecal immunochemical test and colonoscopy screening for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2017;104(8):1078–1086. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bleijenberg N, Drubbel I, Neslo RE, Schuurmans MJ, Ten Dam VH, Numans ME, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a proactive primary care program for frail older people: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(12):1029–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ethgen O, Sanchez Gonzalez Y, Jeanblanc G, Duguet A, Misurski D, Juday T. Public health impact of comprehensive hepatitis C screening and treatment in the French baby-boomer population. J Med Econ. 2017;20(2):162–170. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2016.1232725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mo X, Gai Tobe R, Wang L, Liu X, Wu B, Luo H, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of different types of human papillomavirus vaccination combined with a cervical cancer screening program in mainland China. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):502. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2592-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petry KU, Barth C, Wasem J, Neumann A. A model to evaluate the costs and clinical effectiveness of human papilloma virus screening compared with annual papanicolaou cytology in Germany. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;212:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H, Yang L, Wang F, Zhang L. Strategies and cost-effectiveness evaluation of persistent albuminuria screening among high-risk population of chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):135. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0538-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atkin W, Brenner A, Martin J, Wooldrage K, Shah U, Lucas F, et al. The clinical effectiveness of different surveillance strategies to prevent colorectal cancer in people with intermediate-grade colorectal adenomas: a retrospective cohort analysis, and psychological and economic evaluations. Health Technol Assess. 2017;21(25):1–536. doi: 10.3310/hta21250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barzi A, Lenz HJ, Quinn DI, Sadeghi S. Comparative effectiveness of screening strategies for colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2017;123(9):1516–1527. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campos NG, Sharma M, Clark A, Lee K, Geng F, Regan C, et al. The health and economic impact of scaling cervical cancer prevention in 50 low- and lower-middle-income countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;138(Suppl 1):47–56. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chowers M, Shavit O. Economic evaluation of universal prenatal HIV screening compared with current ‘at risk’ policy in a very low prevalence country. Sex Transm Infect. 2017;93(2):112–117. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coyle K, Carrier M, Lazo-Langner A, Shivakumar S, Zarychanski R, Tagalakis V, et al. Cost effectiveness of the addition of a comprehensive CT scan to the abdomen and pelvis for the detection of cancer after unprovoked venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2017;151:67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crowson MG, Rocke DJ, Hoang JK, Weissman JL, Kaylie DM. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a non-contrast screening MRI protocol for vestibular schwannoma in patients with asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss. Neuroradiology. 2017;59(8):727–736. doi: 10.1007/s00234-017-1859-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devine A, Harvey R, Min AM, Gilder MET, Paw MK, Kang J, et al. Strategies for the prevention of perinatal hepatitis B transmission in a marginalized population on the Thailand-Myanmar border: a cost-effectiveness analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):552. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2660-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ditkowsky J, Shah KH, Hammerschlag MR, Kohlhoff S, Smith-Norowitz TA. Cost-benefit analysis of Chlamydia trachomatis screening in pregnant women in a high burden setting in the United States. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):155. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2248-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrandiz L, Ojeda-Vila T, Corrales A, Martin-Gutierrez FJ, Ruiz-de-Casas A, Galdeano R, et al. Internet-based skin cancer screening using clinical images alone or in conjunction with dermoscopic images: a randomized teledermoscopy trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(4):676–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goede SL, Rabeneck L, van Ballegooijen M, Zauber AG, Paszat LF, Hoch JS, et al. Harms, benefits and costs of fecal immunochemical testing versus guaiac fecal occult blood testing for colorectal cancer screening. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0172864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta N, Langenderfer D, McCormack FX, Schauer DP, Eckman MH. Chest computed tomographic image screening for cystic lung diseases in patients with spontaneous pneumothorax is cost effective. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(1):17–25. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201606-459OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heidari S, Manesh AO, Rajabi F, Moradi-Joo M. Cost-effectiveness analysis of automated auditory brainstem response and Otoacoustic emission in universal neonatal hearing screening. Iran J Pediatr. 2017;27(2):e5229. 10.5812/ijp.5229.

- 30.Horn BP, Crandall C, Forcehimes A, French MT, Bogenschutz M. Benefit-cost analysis of SBIRT interventions for substance using patients in emergency departments. J Subst Abus Treat. 2017;79:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunter SA, Morris C, Nelson K, Snyder BJ, Poulton TB. Digital breast tomosynthesis: cost-effectiveness of using private and Medicare insurance in community-based health care facilities. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;208(5):1171–1175. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.16987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kievit W, Maurits JS, Arts EE, van Riel PL, Fransen J, Popa CD. Cost-effectiveness of cardiovascular screening in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017;69(2):175–182. doi: 10.1002/acr.22929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phisalprapa P, Supakankunti S, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Apisarnthanarak P, Charoensak A, Washirasaksiri C, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of ultrasonography screening for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in metabolic syndrome patients. Med (Baltimore) 2017;96(17):e6585. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Requena-Mendez A, Bussion S, Aldasoro E, Jackson Y, Angheben A, Moore D, et al. Cost-effectiveness of Chagas disease screening in Latin American migrants at primary health-care centres in Europe: a Markov model analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(4):E439–EE47. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saito S, Azumi M, Muneoka Y, Nishino K, Ishikawa T, Sato Y, et al. Cost-effectiveness of combined serum anti-helicobacter pylori IgG antibody and serum pepsinogen concentrations for screening for gastric cancer risk in Japan. Eur J Health Econ. 2017; 10.1007/s10198-017-0901-y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Schiller-Fruehwirth I, Jahn B, Einzinger P, Zauner G, Urach C, Siebert U. The long-term effectiveness and cost effectiveness of organized versus opportunistic screening for breast cancer in Austria. Value Health. 2017;20(8):1048–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tjalma WAA, Kim E, Vandeweyer K. The impact on women’s health and the cervical cancer screening budget of primary HPV screening with dual-stain cytology triage in Belgium. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;212:171–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tufail A, Rudisill C, Egan C, Kapetanakis VV, Salas-Vega S, Owen CG, et al. Automated diabetic retinopathy image assessment software: diagnostic accuracy and cost-effectiveness compared with human graders. Ophthalmol. 2017;124(3):343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meulen MPV, Kapidzic A, Leerdam MEV, van der Steen A, Kuipers EJ, Spaander MCW, et al. Do men and women need to be screened differently with fecal immunochemical testing? A cost-effectiveness analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2017;26(8):1328–1336. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Welton NJ, McAleenan A, Thom HH, Davies P, Hollingworth W, Higgins JP, et al. Screening strategies for atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2017;21(29):1–236. doi: 10.3310/hta21290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams DM, Miller AO, Henry MW, Westrich GH, Ghomrawi HMK. Cost-effectiveness of Staphylococcus aureus decolonization strategies in high-risk total joint arthroplasty patients. J Arthroplast. 2017;32(9S):S91–SS6. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yarnoff BO, Hoerger TJ, Simpson SK, Leib A, Burrows NR, Shrestha SS, et al. The cost-effectiveness of using chronic kidney disease risk scores to screen for early-stage chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):85. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0497-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zimmermann MR, Vodicka E, Babigumira JB, Okech T, Mugo N, Sakr S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of cervical cancer screening and preventative cryotherapy at an HIV treatment clinic in Kenya. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2017;15:13. doi: 10.1186/s12962-017-0075-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haukaas FS, Arnesen TM, Winje BA, Aas E. Immigrant screening for latent tuberculosis in Norway: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Eur J Health Econ. 2017;18(4):405–415. doi: 10.1007/s10198-016-0779-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen X, Yuan M, Lu J, Zhang Q, Sun M, Chang F. Assessment of universal newborn hearing screening and intervention in Shanghai, China. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2017;33(2):206–214. doi: 10.1017/S0266462317000344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Devine A, Parmiter M, Chu CS, Bancone G, Nosten F, Price RN, et al. Using G6PD tests to enable the safe treatment of plasmodium vivax infections with primaquine on the Thailand-Myanmar border: a cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(5):e0005602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gray E, Donten A, Karssemeijer N, van Gils C, Evans DG, Astley S, et al. Evaluation of a stratified National Breast Screening Program in the United Kingdom: an early model-based cost-effectiveness analysis. Value Health. 2017;20(8):1100–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.John D, Parikh R. Cost-effectiveness and cost utility of community screening for glaucoma in urban India. Public Health. 2017;148:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim DY, Han KH, Jun B, Kim TH, Park S, Ward T, et al. Estimating the cost-effectiveness of one-time screening and treatment for hepatitis C in Korea. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0167770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morton R, Sayma M, Sura MS. Economic analysis of the breast cancer screening program used by the UK NHS: should the program be maintained? Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press) 2017;9:217–225. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S123558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mullie GA, Schwartzman K, Zwerling A, N'Diaye DS. Revisiting annual screening for latent tuberculosis infection in healthcare workers: a cost-effectiveness analysis. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):104. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0865-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ten Haaf K, Tammemagi MC, Bondy SJ, van der Aalst CM, Gu S, SE MG, et al. Performance and cost-effectiveness of computed tomography lung cancer screening scenarios in a population-based setting: a microsimulation modeling analysis in Ontario, Canada. PLoS Med. 2017;14(2):e1002225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Katwyk S, Jin YP, Trope GE, Buys Y, Masucci L, Wedge R, et al. Cost-utility analysis of extending public health insurance coverage to include diabetic retinopathy screening by optometrists. Value Health. 2017;20(8):1034–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang SC, Lai WW, Lin CC, Su WC, Ku LJ, Hwang JS, et al. Cost-effectiveness of implementing computed tomography screening for lung cancer in Taiwan. Lung Cancer. 2017;108:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Albright CM, MacGregor C, Sutton D, Theva M, Hughes BL, Werner EF. Group B streptococci screening before repeat cesarean delivery: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(1):111–119. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cressman S, Peacock SJ, Tammemagi MC, Evans WK, Leighl NB, Goffin JR, et al. The cost-effectiveness of high-risk lung cancer screening and drivers of program efficiency. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(8):1210–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim JJ, Burger EA, Sy S, Campos NG. Optimal cervical cancer screening in women vaccinated against human papillomavirus. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Lew JB, St John DJB, Xu XM, Greuter MJE, Caruana M, Cenin DR, et al. Long-term evaluation of benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program in Australia: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2017; 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30105-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Pil L, Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Kruse V, Tromme I, Speybroeck N, et al. Cost-effectiveness and budget effect analysis of a population-based skin cancer screening. JAMA Dermatol. 2016; 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4518. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Roberts K, Cannon J, Atkinson D, Brown A, Maguire G, Remenyi B, et al. Echocardiographic screening for rheumatic heart disease in indigenous Australian children: a cost-utility analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(3):e004515. 10.1161/JAHA.116.004515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Sharma M, Seoud M, Kim JJ. Cost-effectiveness of increasing cervical cancer screening coverage in the Middle East: an example from Lebanon. Vaccin. 2017;35(4):564–569. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Teng AM, Kvizhinadze G, Nair N, McLeod M, Wilson N, Blakely T. A screening program to test and treat for helicobacter pylori infection: cost-utility analysis by age, sex and ethnicity. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):156. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2259-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim JJ, Burger EA, Sy S, Campos NG. Optimal cervical cancer screening in women vaccinated against human papillomavirus. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rodriguez-Perez MC, Orozco-Beltran D, Gil-Guillen V, Dominguez-Coello S, Almeida-Gonzalez D, Brito-Diaz B, et al. Clinical applicability and cost-effectiveness of DIABSCORE in screening for type 2 diabetes in primary care. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;130:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Selvapatt N, Ward T, Harrison L, Lombardini J, Thursz M, McEwan P, et al. The cost impact of outreach testing and treatment for hepatitis C in an urban drug treatment unit. Liver Int. 2017;37(3):345–353. doi: 10.1111/liv.13240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cadier B, Bulsei J, Nahon P, Seror O, Laurent A, Rosa I, et al. Early detection and curative treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a cost-effectiveness analysis in France and in the United States. Hepatol. 2017;65(4):1237–1248. doi: 10.1002/hep.28961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]