Abstract

Background:

Tremendous infectious disease burden and rapid emergence of multidrug resistant pathogens continues to burden our healthcare system. Antibiotic stewardship program often implements antibiotic policies that help in preventing unnecessary use of antibiotics and in optimizing management. To develop such a policy for management of infections in the emergency unit, it is important to analyze the information regarding antibiotic prescription patterns in patients presenting to the emergency room referred from various healthcare settings. This study was conducted with the aforementioned background.

Methods:

We conducted a prospective observational study in triage area of emergency unit of a tertiary care hospital. All the referred patients were screened for antibiotic prescription. Data extraction form was used to capture information on patient demographics, diagnosis and antibiotics prescribed. Antibiotic prescription details with regard to dosage, duration and frequency of antimicrobial administration were also recorded. Data were summarized using descriptive statistics as appropriate.

Results:

Out of 517 screened patients, 300 were prescribed antimicrobials. Out of 29 antibiotics prescribed, 12 were prescribed in more than 90% of patients. Broad spectrum antibiotics accounted for 67.3% of prescriptions. In 129 out of 300 patients, no evidence of infectious etiology was found.

Conclusion:

Our study highlights some common but serious lapses in antibiotic prescription patterns in patients referred from various healthcare settings. This emphasizes the need to provide training for rational use of antibiotics across healthcare settings.

Keywords: antimicrobial resistance, antimicrobial stewardship, prescription

Introduction

Communicable diseases continue to be important contributors of morbidity and mortality worldwide. As per the recent estimates, the crude death rate due to infectious causes in India is about 416.75 deaths per 100,000 persons.1 Furthermore, prevalence of multidrug resistant pathogens is increasing rapidly, especially, in the hospital settings.2 High infectious disease burden, poor living conditions and easy availability of antibiotics are some of the major drivers of rising antimicrobial resistance in India.1,3

Multidrug resistant strains have been widely documented for Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in India.4 The infections caused by aforementioned organisms are not only difficult to treat because of limited number of available antimicrobial choices but also lead to increased treatment duration and associated costs. Unfortunately, India represents the country with highest antimicrobial consumption.5 Furthermore, overuse of antimicrobials is causally linked to emergence of antimicrobial resistance.6,7 Thus, one of the logical ways for curtailing antimicrobial resistance is to reduce inappropriate or irrational antibiotic prescribing. Antibiotic stewardship programs often target such irrational use of antimicrobials.8 These programs are widely practiced in developed countries and have been shown to decrease antimicrobial consumption, improve patient outcomes and combat emergence of resistant strains.9 Antimicrobial resistance adds to the economic burden, particularly, for lower and middle-income countries.10 The dwindling pipeline of new antibiotics makes the situation very grim.11

In developing countries, antimicrobial stewardship programs are emerging up only recently. One such program has been initiated in our institute where an approach of ‘assess, propose and implement’ is being followed.12 One of the activities of this program is to develop antibiotic policies for management of infections in various settings. Patients are often referred to our emergency department from other healthcare settings such as other hospitals, primary and secondary health centers, nursing homes and stand-alone clinics. These patients quite frequently need admission either to the wards or in the intensive care units. For want of available space, these patients sometime continue to be managed in areas which are called emergency wards. In these wards, certain medications and articles required for patient management are available free of cost. However, for want of supplies, patients may need to make out of pocket payments for procurement of medicines, including antibiotics.

Prior to formulating antimicrobial guidelines for patients in this area, it was felt important by stakeholders to understand the prescription patterns of antimicrobials of referring healthcare units. Furthermore, it was also felt important to understand the information based on which diagnosis of infective state was made including investigations such as culture and sensitivity reports. As pointed out earlier, a large number of these patients are subsequently moved to inpatient settings (wards or intensive care units), where they add to the burden of resistant organisms and contribute toward elevated defined daily dosage of restricted antimicrobials. This study was undertaken with this background to provide an input about the prescription patterns of antibiotics in referred patients for formulating antibiotic policy for the emergency medical ward.

Methodology

We conducted a prospective observational study over a period of 5 months (i.e. October 2016–February 2017) in the triage area of our tertiary care hospital. The triage area of emergency medical outpatient department is the place where the patient is first met by a junior doctor. No intervention is initiated unless the patient requires emergency resuscitation. The study was initiated after obtaining due approval from the Institute Ethics Committee. A waiver of informed consent of patient was obtained from the Ethics Committee. We collected data on all patients received in the triage area between 8 a.m. and 5 p.m. during the study period. All patients who were referred from any hospital, clinic and nursing home were assessed for antibiotic use, either ongoing or preadministered (during the stay in the referring unit). Various sources used for extracting this information included patient referral notes, discharge summary, prescription slip, left-over medicines with the patient, slip issued by chemists and recall by the patient or his or her attendant (in case none of the aforementioned sources were available).

Data extraction forms were used to record information on demographic details, provisional/definitive diagnosis and antibiotics received by the patients from the point of referral. Following information was collected from either the patient or his or her attendant: (1) a brief description/referral note of the current illness, (2) presenting complaints, (3) investigations done previously, (4) interventions done previously and (5) name of the city/hospital of referring facility/doctor. We further analyzed source of information for pertinent details such as antimicrobial dosage, frequency, duration of antimicrobial use and whether such use was indicated by documented culture sensitivity reports or not. A possibility of infective etiology was considered plausible if the patient had any of the following at any time prior to inclusion in the study: (1) fever, (2) increased leukocyte count, (3) signs and symptoms of infection of a particular organ system and (4) sepsis.

The collected data were summarized using descriptive statistics as appropriate. Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation. Discrete variables were presented as proportions and percentages. We further assessed percentage of individuals in whom the initiation of antibiotic at point of care was inappropriate based on possibility of infective etiology as suggested by above four criteria.

Results

In this prospective study, we screened 517 patients who reported in the aforementioned area. Out of these 517 patients, 300 (58%) were prescribed antimicrobials. The referral note was the most frequently used source for extracting information with regard to antibiotic prescription. The prescription patterns of these patients were taken up for further evaluation.

Demographic profile

180 patients (60%) were men and 120 patients (40%) were women. Mean (±SD) age of the study participants was 45 ± 18 years (ranging 13–95 years). Maximum numbers of patients were in the age group of 30–70 years (36%). 183 patients (61%) were referred by public sector healthcare setups, 116 (38.6%) by the private clinics and 92 (30.6%) by facilities affiliated to teaching institutes. The patients were referred from the following states in descending order: Punjab (40%), Haryana (20%), Himachal Pradesh (10%) and Uttar Pradesh (5%). 25% referrals were from Chandigarh (a union territory).

Antibiotic prescription pattern

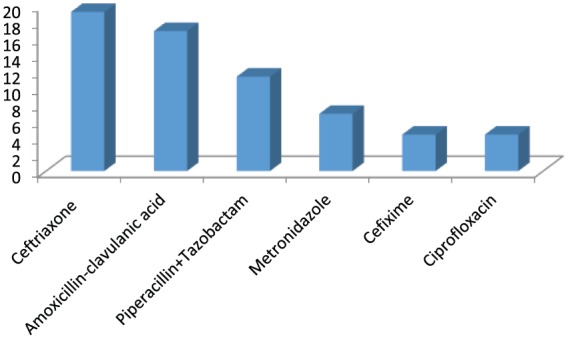

Different types of provisional diagnosis recorded in the referral notes were 70 in number. Fever (with or without thrombocytopenia), acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), sepsis and pneumonia accounted for 37% of cases. In total, 29 different antibiotics were prescribed to various patients. 12 antibiotics accounted for more than 80% of prescriptions. Out of these, ceftriaxone and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid were prescribed most commonly (19.2% and 16.9%, respectively). This was followed by piperacillin-tazobactam given to 41 (11.4 %) patients. Details of different antibiotics and their prescription frequencies have been presented in Table 1. Six antibiotics were prescribed to more than 5% of patient population (Figure 1). Broad spectrum antibiotics accounted for 240 (67.3%) of prescriptions. Details of antibiotic prescription with respect to mention of dosage, frequency, duration of use and whether such use was based on documented culture sensitivity reports are presented in Table 2. Culture sensitivity reports were not available in any of the case, which means that the antibiotics were started empirically and an attempt for possible de-escalation subsequently was not made. In 129 out of 300 (43.9%) patients, no evidence of infectious etiology was found with respect to presence of any fever, elevated leucocyte counts, signs and symptoms of infection of organ system or sepsis. Thus, antibiotic use was considered unnecessary in these patients.

Table 1.

List of antibiotics prescribed.

| S. no. | Antibiotics | Percentage of antibiotics prescribed |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ceftriaxone | 69 (19.2) |

| 2 | Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 61 (16.9) |

| 3 | Piperacillin and tazobactam | 41 (11.4) |

| 4 | Metronidazole | 25 (6.9) |

| 5 | Cefixime | 16 (4.4) |

| 6 | Ciprofloxacin | 16 (4.4) |

| 7 | Azithromycin | 14 (3.8) |

| 8 | Levofloxacin | 14 (3.8) |

| 9 | Norfloxacin | 14 (3.8) |

| 10 | Clindamycin | 11 (3.1) |

| 11 | Amikacin | 10 (2.7) |

| 12 | Vancomycin | 9 (2.5) |

| 13 | Moxifloxacin | 8 (2.2) |

| 14 | Ofloxacin | 7 (1.9) |

| 15 | Meropenem | 7 (1.9) |

| 16 | Rifaximin | 5 (1.4) |

| 17 | Isoniazid | 4 (1.1) |

| 18 | Rifampicin | 4 (1.1) |

| 19 | Pyrazinamide | 4 (1.1) |

| 20 | Ethambutol | 4 (1.1) |

| 22 | Gentamicin | 3 (0.8) |

| 23 | Amoxicillin | 3 (0.8) |

| 24 | Colistin | 3 (0.8) |

| 25 | Tinidazole | 2 (0.5) |

| 26 | Imipenem | 2 (0.5) |

| 27 | Cefuroxime | 1 (0.3) |

| 28 | Chloramphenicol | 1 (0.3) |

| 29 | Cefoperazone and sulbactam | 1 (0.3) |

Figure 1.

List of six commonly prescribed antibiotics.

Table 2.

Types of inappropriate use observed in prescriptions.

| Type of inappropriate use | No. of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Dose not mentioned | 43 (14.3) |

| Frequency of administration not mentioned | 300 (100) |

| Duration not mentioned | 282 (94) |

| Susceptibility pattern not defined | 300 (100) |

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report antibiotic prescription pattern of the patients referred from various healthcare centers to a tertiary care hospital setup. Our emergency department receives patients from a variety of healthcare settings such as stand-alone clinics, private nursing homes and hospitals, primary and secondary level public sector health centers and hospitals. Thus, we believe that our study sample is largely representative of emergency settings of tertiary care facilities of our country.

We found that antimicrobials were clearly not indicated in more than 40% of cases, which represent significant overuse of antimicrobials. Diagnosis of infection may not always be very clear. Moreover terminologies used for categorizing infections may be highly variable. For example, fever with and without thrombocytopenia, tropical fever, pyrexia of unknown origin, fever with sepsis, fever with pain abdomen and dengue fever were all recorded as provisional diagnosis. Furthermore, determining or ruling out bacterial etiology as a cause of ongoing infection may be even more challenging.13,14 Importantly, this study was not conducted in the period when viral infections, for example, dengue or swine flu, are common. We believe that this percentage of inappropriate use of antimicrobials may be further pushed up in a scenario of increased incidence of viral infections had the study been conducted during such period as has been reported previously.15 A considerable percentage (>65%) of prescriptions were that of broad spectrum antimicrobials such as amoxicillin clavulanic acid, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, clindamycin and piperacillin-tazobactam. This can be expected as 100% patients in the study cohort were started on empirical antibiotic therapy. For empiric management of infections, it may be necessary to use broad spectrum antimicrobials initially. Prudence may still be exercised for instance, use of amoxicillin instead of co-amoxiclav, minimizing use of third and fourth generation of cephalosporins and reducing fluoroquinolone use that have been shown to have a bearing on decreasing antimicrobial resistance.16 However, absence of culture sensitivity reports highlights the fact that the importance of de-escalation subsequently was not understood by most of the prescribers. This in a way identifies a target for any educational activity as part of antibiotic stewardship program that may be planned subsequently.

Although the use of broad spectrum antibiotics was high, it was interesting to observe that contrary to popular belief, carbapenems and polymyxins were prescribed to fewer than 12 (3.2%) patients. This leaves scope for considerable options for empirical management of infections in the emergency unit. National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), India, has recently come up with national antibiotic policy for management of infections at all levels of healthcare.17 It is important to propagate these guidelines as these will help in guiding rational use of antibiotics. Lesson can be drawn from such initiatives in other developing countries such as South Africa18 and Namibia.19

Other important findings were incomplete discharge summaries or referral notes with regard to lack of complete data on antimicrobial use (in terms of drug dosage, frequency and duration), whether any diagnostic investigations were done, and lack of data on culture and sensitivity reports. These serious lapses not only highlight deficiencies in the management of patient but also makes further patient management difficult. Therefore, it must be emphasized that complete discharge and referral notes be issued with details of treatment given and details of all investigations and interventions done in the patient.

Limitations of our study include failure to include all patients who reported to triage area after 5 p.m. This was largely because of limitation of available resources in terms of personnel. The study was not conducted in a period when viral illnesses such as dengue, H1N1 swine flu are common; therefore, results of this study may not be representative of antibiotic prescribing trends in such periods. Nevertheless, we prospectively screened 517 patients and captured pertinent information on 300 patients with regard to prescription pattern of antibiotics and identified different kinds of deficiencies in referral notes.

Our study has thus outlined the irrational antibiotic prescribing trends in the referral setups (both public and private) of our country. This information will be used to devise antibiotic guidelines for empirical management of patients in emergency area. Furthermore, the targets for intervention in referring healthcare setups such as education regarding making appropriate empiric antibiotic choices, de-escalation, culture of sending cultures and writing details of treatment given may be further evaluated in future.

Conclusion

Our study brings to the fore some common but serious lapses in antibiotic prescription patterns in referred patients and emphasizes the need for proper referral and appropriate use of antibiotics. We have formulated an e-course on antimicrobial stewardship taking into consideration the practice settings and issues pertinent to developing countries. The findings of this study have helped in designing some of the modules of the educational intervention designed for healthcare settings with absent or negligible access to training in rational use of antimicrobials.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest statement: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Amritpal Kaur, Antimicrobials Stewardship, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Rajan Bhagat, Department of Pharmacology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Navjot Kaur, Department of Pharmacology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Nusrat Shafiq, Department of Pharmacology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Vikas Gautam, Department of Medical Microbiology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Samir Malhotra, Department of Pharmacology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Vikas Suri, Department of Internal Medicine, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Ashish Bhalla, Department of Internal Medicine, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

References

- 1. Laxminarayan R, Chaudhury RR. Antibiotic resistance in India: drivers and opportunities for action. PLoS Med 2016; 13: e1001974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zilahi G, Artigas A, Martin Loeches I. What’s new in multidrug resistant pathogens in the ICU? Ann Intensive Care 2016; 6: 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laxminarayan R, Matsoso P, Pant S, et al. Access to effective antimicrobials: a worldwide challenge. Lancet 2015; 387: 168–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patel I, Hussain R, Khan A, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in India. J Pharm Policy Pract 2017; 10: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Van Boeckel TP, Gandra S, Ashok A, et al. Global antibiotic consumption 2000 to 2010: an analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14: 742–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Llor C, Bjerrum L. Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2014; 5: 229–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bell BG, Schellevis F, Stobberingh E, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of antibiotic consumption on antibiotic resistance. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shafiq N, Kumar MP, Kumar G, et al. Antimicrobial Stewardship Program of Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh: running fast to catch the missed bus. J Postgrad Med Educ Res 2017; 51: 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE, et al. Infectious diseases society of America and the society for healthcare epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44: 159–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O’Neill J. Securing new drugs for future generations: the pipeline of antibiotics, https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/SECURING%20NEW%20DRUGS%20FOR%20FUTURE%20GENERATIONS%20FINAL%20WEB_0.pdf (2015, accessed 20 January, 2018).

- 11. World Bank Group. Drug-resistant infections: a threat to our economic future, Final report, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/323311493396993758/pdf/114679-REVISED-v2-Drug-Resistant-Infections-Final-Report.pdf (2017, accessed 20 January, 2018).

- 12. Shafiq N, Kumar MP, Gautam V, et al. Antibiotic stewardship in a tertiary care hospital of a developing country: establishment of a system and its application in a unit-GASP Initiative. Infection 2016; 44: 651–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rolston KV. Challenges in the treatment of infections caused by Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria in patients with cancer and neutropenia. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 40(Suppl. 2): S46–S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mashalla Y, Setlhare V, Massele A, et al. Assessment of prescribing practices at the primary healthcare facilities in Botswana with an emphasis on antibiotics: findings and implications. Int J Clin Pract 2017; 71: e13042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Landstedt K, Sharma A, Johansson F, et al. Antibiotic prescriptions for inpatients having non-bacterial diagnosis at medicine departments of two private sector hospitals in Madhya Pradesh, India: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2017; 7: e012974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. De bias S, Kaguelidou F, Verhamme KM, et al. Using prescription patterns in primary care to derive new quality indicators for childhood community antibiotic prescribing. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2016; 35: 1317–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Centre for Disease Control. National treatment guidelines for antimicrobial use in infectious diseases (version 1.0), http://ncdc.gov.in/writereaddata/mainlinkfile/File622.pdf (2016, accessed 9 January, 2018)

- 18. Schellack N, Stokes J, Meyer JC, et al. Ongoing initiatives to improve the quality and efficiency of medicine use within the Public Healthcare System in South Africa; a preliminary study. Front Pharmacol 2017; 8: 751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nakwatumbah S, Kibuule D, Godman B, et al. Compliance to guidelines for the prescribing of antibiotics in acute infections at Namibia’s national referral hospital: a pilot study and the implications. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2017; 15: 713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]