Abstract

Background:

Chylous ascites is an uncommon presentation of mycobacterial infection.

Methods:

We report three cases of tubercular chylous ascites, and in addition, we performed a systematic review of the published literature for the clinical presentation, treatment, and outcomes of mycobacterial chylous ascites. We followed the PRISMA guidelines for the systematic review.

Results:

A total of 33 cases (including three of ours) were included. The mean age of the reported cases was 32.54 ± 17.56 years, and a male predominance (76%) was noted. The predominant clinical features were abdominal distension, abdominal pain, fever and loss of appetite and weight. Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) and Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAC) infection were responsible for 16 and 15 cases, respectively. All patients with MAC related chylous ascites had HIV infection. The mechanisms were related to lymph nodal enlargement, constrictive pericarditis and remote scrofuloderma. Overall, there was 29% mortality. Use of anti-mycobacterial therapy with use of total parenteral nutrition, octreotide and medium chain triglyceride-based diet resulted in improvement in the rest of the cases. The cause of death in our case was anti-tubercular therapy-induced hepatitis; three deaths were due to disseminated mycobacterial infection, one due to cardiopulmonary failure and unknown in four patients.

Conclusion:

Chylous ascites due to mycobacterial infection is uncommon and associated with poor outcome. However, early diagnosis and nutritional management along with antimycobacterial therapy can improve outcome.

Keywords: ascites, chylous, HIV, peritonitis, tuberculosis

Introduction

Chylous ascites is a type of peritoneal fluid accumulation where the fluid has a turbid hue due to the presence of chyle thereby resulting in high triglyceride (TG) level in the fluid.1 A large number of conditions have been implicated in the causation of this entity and include cirrhosis, malignancies, traumatic or surgical injury to lymphatic system, right-sided heart failure, radiation, pericarditis, pancreatitis, tuberculosis and filariasis in adults.1,2 In children, congenital lymphatic abnormalities and trauma are considered the most common etiological factors.2 Chylous ascites, apart from the TGs and nutrients, is rich in immunoglobulins and therefore its occurrence may predispose the affected individuals to malnutrition, immunosuppression and adverse outcomes. Prompt recognition of the underlying etiological factor and mechanism may therefore guide treatment to help avoid adverse outcomes in these patients.

The literature regarding mycobacterial infection–related chylous ascites has been published primarily in the form of case reports and small case series.3–24 We present three cases of chylous ascites due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB; tubercular chylous ascites) and review the published literature about mycobacterial (both tubercular and Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare, i.e., MAC) associated chylous ascites.

Case series

Case 1

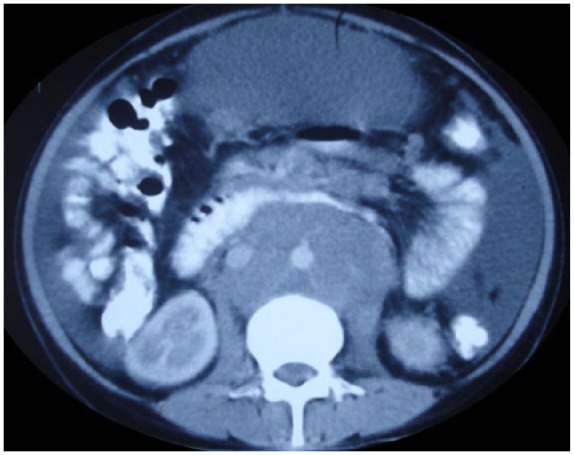

A 25-year-old female patient presented to our hospital with the complaint of progressive abdominal distension for 6 months. She also reported to have abdominal pain, fever, loss of appetite and loss of weight of 8 kg in 6 months. On examination, she was found to have multiple cervical and axillary lymph nodes. Examination of the ascitic fluid revealed milky white in colour, with a white cell count of 500 (lymphocyte dominant), total protein 4.1 g/dl, TG 1600 mg/dl, and adenosine deaminase (ADA) 73 IU/l. Serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) was calculated to be 0.5. Stain for acid fast bacilli (AFB) was negative and cytological examination was negative for malignant cells. Ascitic fluid culture did not grow any Mycobacterium. In abdominal computed tomography (CT), there was gross ascites with multiple necrotic lymph nodes in mesentery and retroperitoneum (Figure 1) with circumferential mural thickening involving terminal ileum, ileocecal valve and caecum. Mantoux skin test was found to be positive and ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) from retroperitoneal lymph nodes showed granulomatous inflammation and AFB stain was positive. Also, Xpert Mtb/Rif was positive for MTB tuberculosis. Colonoscopy showed multiple ulcers in ascending colon, caecum and biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation and AFB stain was positive. Serology for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was negative. She was started on antitubercular therapy with isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol. For control of ascites, she was started on medium chain triglyceride (MCT) based diet and started on octreotide. The weight of the patient stabilised and abdominal girth reduced. At 3 months of follow-up, the patient was well and her symptoms and ascites had resolved.

Figure 1.

CT of patient showing sheet like mass of retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy and ascites.

Case 2

A 26-year-old female patient presented to our hospital with the complaint of progressive abdominal distension for last 2 months. She also reported to have abdominal pain, loss of appetite and loss of weight. On examination, she was found to have multiple cervical lymph nodes. Examination of the ascitic fluid revealed milky white colour, with a white cell count of 180/mm3 (lymphocyte dominant), total protein 5 g/dl, TG 300 mg/dl, ADA 18 IU/l and SAAG was calculated to be 0.3. Stain for AFB was negative and cytological examination was negative and did not reveal any malignant cells. Chest X ray showed miliary shadows. On abdominal CT, there was gross ascites with omental nodularity with a sheet-like lymph nodal mass encasing inferior vena cava with calcification. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) from cervical lymph node showed granulomatous inflammation and AFB stain was positive. She was started on anti-tubercular therapy with isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol. HIV was negative. For the control of ascites, she was advised MCT-based diet. However, the patient was admitted a week later with severe antituberculosis treatment (ATT)-related hepatitis associated with acute liver failure and later succumbed to liver failure.

Case 3

A 25-year-old female patient presented with the complaint of progressive abdominal distension for last 2 months. She also reported to have loss of appetite and loss of weight. Examination of the ascitic fluid revealed milky white in colour, with a white cell count of 900/mm3 (lymphocyte dominant), total protein 4.2 g/dl, TG 241 mg/dl, and ADA 74 IU/l. SAAG was calculated to be 0.2. Stain for AFB was negative and cytological examination did not reveal any malignant cells. Ascitic fluid culture did not show any mycobacterial growth. In abdominal CT, there was gross ascites with multiple lymph nodes in mesentery. Skin purified protein derivative (PPD) was found to be anergic and FNAC from cervical lymph node showed granulomatous inflammation and AFB stain was positive. She was started on anti-tubercular therapy with isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol. For control of ascites, she was given MCT-based diet. The patient improved with resolution of ascites and pleural effusion. She completed 6 months of daily ATT and is doing well 5 months after completion of treatment.

Methods

Literature search

We searched PubMed with the search strategy chylous ascites AND tuberculosis up until August 2017. All published reports in the English language were considered for inclusion. A total of 42 results were retrieved. Of these, 26 results were relevant and after reading abstract or full article it was found that five were other languages, four were unrelated and one was a review article. We also searched EMBASE with the strategy chylous ascites AND tuberculosis. Of the 28 results retrieved from EMBASE, 20 were duplicates, six other languages. In all, 18 results were considered for inclusion. Further searching these papers, additional four cases were retrieved from the references. Therefore, in all 33 cases, including three of our cases, were included in the final analysis (Figure 2).1–25

Figure 2.

Selection of papers for the review.

Diagnosis, treatment and outcomes

The diagnosis of mycobacterial infection was established by demonstration of the organism on culture, or nucleic acid–based polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests. For tubercular chylous ascites, the diagnosis was also established by demonstration of AFB, presence of caseating granulomas on histology and response to ATT or elevated adenosine deaminase (> 39 U/L) in the ascitic fluid. For the diagnosis of MAC-related chylous ascites, the growth of MAC on culture was considered as the diagnostic standard. The clinical presentation, temporal relation of onset of chylous ascites with treatment (prior to treatment or after initiation of treatment), evaluation (imaging, fluid analysis, lymphangiography or lymphoscintigraphy) were recorded. The treatment which was provided in each of the cases like anti-mycobacterial treatment, total parenteral nutrition (TPN), somatostatin analogues or use of MCTs and the response with outcomes were also recorded. We also compared the clinical features of tubercular- and MAC related chylous ascites.

Results

The mean age of presentation of these 33 patients was 32.54 ± 17.56 years. The youngest patient was just 19 days old and eldest was 73 years. Of all the reported cases, 25 (75.76%) were men and 8 were women suggesting a male predominance of this condition. This male prevalence could be due to higher prevalence of tuberculosis in males. In all patients, the primary presentation was abdominal distension. Abdominal pain was present in 14 out of 22 reported cases and data were not available for 11 patients. Fever was present in 17 out of 25 cases, diarrhoea was present 5 out of 17 reported cases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical features of patients with tubercular and MAC related chylous ascites.

| MTB (n = 16) | MAC (n = 15) | Total (n = 33)* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 27.8 ± 19.9 | 34.4 ± 14.4 | 32.5 ± 17.5 |

| Gender (male) | 10 (62.5%) | 14 (93.3) | 25 (75.8%) |

| Abdominal pain | 7/13 (53.8%) | 7/9 (77.8%) | 14/22 (63.6%) |

| Distension | 16/16 (100%) | 15/15 (100%) | 33/33 (100%) |

| Fever | 11/15 (73.3%) | 6/10 (60%) | 17/25 (68%) |

| LOA/LOW | 9/10 (90%) | 5/9 (55.6%) | 14/20 (70%) |

| HIV | 5/11 (45.4%) | 15/15 (100%) | 20/26 (76.9%) |

| Mantoux | 4/8 (50%) | 0/0 | 4/8 (50%) |

| Chest involvement | 7/11 (63.6%) | 0/2 | 9/15 (60%) |

| Other organ involvement | 11/16 (68.8%) | 14/15 (93.3%) | 27/33 (81.8%) |

| Outcome (Death) | 3/15 (20%) | 6/14 (42.9%) | 9/31 (29.0%) |

MAC, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare; MTB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Of the 33 cases, 16 had MTB, 15 had MAC and two cases had remote infection: one with scrofuloderma and other with constrictive pericarditis.

Ascitic fluid TG values were available for 26 patients and data were not available for seven patients. The median TG value was 655 mg/dl with seven patients having more than 1000 mg/dl. The minimum TG value was 169 mg/dl and the maximum TG value was 4521 mg/dl. The SAAG value was available for six patients, two patients having high SAAG (⩾ 1.1) and four patients having low SAAG. Values of ascitic fluid adenosine deaminase (ADA) were available for seven patients, the mean ADA value in ascitic fluid was 42.9 ± 23.5 IU/l and five patients having value of more than 39 IU/l which is often used as cut off for diagnosis of tubercular ascites. AFB stain of ascitic fluid are positive for 3 out of 22 reported cases and information about AFB stain are not available for rest 11 cases. Ascitic fluid culture was positive for Mycobacterium in 8 out of 23 reported cases and no information available for rest 10 patients; 5 were positive for MTB and 3 for MAC. MTB PCR was positive for three out of five reported cases. Mantoux test was positive in 4 out of 8 reported cases, and no information was available in rest 25 cases.

Twenty-six out of 28 reported cases had intra-abdominal lymph nodes. Most common group of lymph node involvement was mesenteric followed by retroperitoneal lymph nodes. In two patients, the site of lymph nodal involvement was not mentioned and one patient had lymph node tuberculosis in childhood while another patient had underlying chronic kidney disease and was on automated peritoneal dialysis. In one report, tuberculosis-related constrictive pericarditis was reported as the cause of chylous ascites and chylothorax in a HIV-positive patient indicating that mechanisms other than lymphnodal obstruction may be responsible for the genesis of chylous ascites. Associated pleural effusion was present in 7 out of 13 reported cases, and no data were available for rest of the 20 patients. All patients reported to have pleural effusion had chylous effusions including three of our cases. The reported imaging findings, other than presence of lymphadenopathy with or without central hypodensity, included presence of ascites, demonstration of fat fluid level which shifts with changing the patients’ position.4,5

The basis of diagnosis was AFB stain, culture of the organism, PCR testing and histopathology. AFB stain was positive in eight patients, culture was positive in 13 cases, PCR positive in 3 cases and histopathology was the basis of diagnosis in 7 patients. Ascitic fluid analysis was helpful in the diagnosis of mycobacterial infection in 10 patients while rest of the patients required sampling of other sites for diagnosis of mycobacterial infection. Lymphangioscintigraphy was done in three patients including one of our patient. Two of them did not reveal any leak including our patient and one patient revealed non-visualisation of cysterna chyli with thoracic duct irregularity. Of the total 33 cases, MTB was responsible for 16 cases and MAC in 15 patients. One patient developed chylous ascites due to constrictive pericarditis, and another patient due to childhood lymph node tuberculosis. All patients with MAC infections were HIV positive, 5 out of 16 MTB infected patients were HIV positive. Except three patients, all patients received ATT. The patient with childhood lymph node TB and constrictive pericarditis were not treated with ATT and data for one patient is not available. TPN was used as treatment in 7 out of 12 patients reported and data not available for 21 patients. MCT-based diet used as treatment in 10 patients and octreotide used for treatment in two patients. Overall, 9 out of 31 patients (29.03%) died and outcome data for two patients was not available. The cause of death in our case was ATT induced hepatitis, three deaths were due to disseminated mycobacterial infection, one due to cardiopulmonary failure and the cause of death of rest four patients was not available.

Discussion

A number of mechanisms may be responsible for the genesis of chylous ascites in patients with mycobacterial infection. These may include obstruction of the lymphatic system due to enlarged lymph nodes or lymph nodal fibrosis. A case of tuberculosis-related constrictive pericarditis causing chylous ascites has been reported and the possible mechanism in these cases may be related to dilatation of lymphatics resulting from increase in hepatic venous pressures.1,16 Mycobacterial chylous ascites has been reported to occur variably in relation to the disease: as a presenting manifestation wherein the abdominal lymphadenopathy may be responsible for genesis, after treatment or after initiation of antitubercular therapy which may be related to a paradoxical reaction or immune reconstitution related increase in lymph nodal size, or due to remote tubercular infection possible as a result of lymph nodal fibrosis resulting as a sequel of treated tubercular lymphadenitis.12,14,22

Chylous ascites can result from a number of diseases, and the differential diagnosis includes cirrhosis and malignancy. This is apart from causes like trauma or surgical injury to lymphatics which may occur due to a variety of procedures.26 Although the SAAG is expected to be low in patients with tubercular chylous ascites, two of the patients had high SAAG suggestive of portal hypertension in one reported series. Both these patients had MAC related chylous ascites, but the cause of high SAAG is unclear.19 Further, in one report, elevation of tumour marker CA 125 in tubercular chylous ascites was reported. It is well recognised that tubercular ascites and malignant ascites are close mimics and a firm diagnosis should be established only after a histological/cytological evidence.25

Furthermore, it appears that chylous ascites is associated with poor outcomes as 29% of the patients died. This may be related to underlying HIV infection, malnutrition and immune suppression related to chylous ascites. However, guided therapy to treat the underlying infection and use of MCT diet with octreotide may be helpful in most cases. The use of TPN has been reported but adds to the cost of therapy. Use of surgery has not been reported primarily because the genesis is not related to injury or disruption of major lymphatic channels.

Another important finding of the present review is the need to exclude underlying HIV. Furthermore, in patients with underlying HIV infection, MAC is the more likely etiological agent. The diagnosis of MAC can be confused with tuberculosis as both organisms could demonstrate AFB positivity. Therefore, appropriate cultures from peritoneal or tissue specimen must be done in every case with underlying HIV infection. The treatment of MAC is longer and needs addition of clarithromycin to rifampin and ethambutol. Furthermore, the parameters to assess response are not clear. Stabilisation of weight, resolution of abdominal distension and ascites on ultrasound with improvement in well-being suggest response to therapy. However, in cases, there is worsening of ascites the possibility of a misdiagnosis, drug-resistant tuberculosis or a paradoxical or immune reconstitution must be considered.

To conclude, mycobacterial chylous ascites, although uncommon, is treatable in most cases. An underlying mycobacterial infection and HIV must be excluded in patients with chylous ascites. Therapy directed at underlying infection (antimycobacterial therapy) and the use of MCT-based diet and somatostatin or its analogues may help in alleviation of the symptoms. TPN may be used in non-responsive cases, although it adds to the cost of therapy.

Acknowledgments

B.M. contributed towards literature search, drafting and revision of the manuscript, and approval to final version; H.S.M. contributed towards care of the patients and approval to final version; S.A. helped in literature search and approved the final version; U.D. contributed to care of the patients and approval to final version; H.S.: care of the patients and approval to final version; and V.S. conceived the study and helped in literature search, patient care, manuscript drafting, revision and approval to final version. B.M. and V.S. contributed equally to the study.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest statement: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Vishal Sharma  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2472-3409

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2472-3409

Contributor Information

Bipadabhanjan Mallick, Department of Gastroenterology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India.

Harshal S. Mandavdhare, Department of Gastroenterology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

Sourabh Aggarwal, University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC), Omaha, NE, USA.

Harjeet Singh, Department of General Surgery, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India.

Usha Dutta, Department of Gastroenterology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India.

Vishal Sharma, Department of Gastroenterology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India.

References

- 1. Lizaola B, Bonder A, Trivedi HD, et al. Review article: the diagnostic approach and current management of chylous ascites. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017; 46: 816–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kumar A, Mandavdhare HS, Rana SS, et al. Chylous ascites due to idiopathic chronic pancreatitis managed with endoscopic stenting. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2018; 42: e29–e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Emınler AT, Ayyildiz T, Irak K, et al. Tuberculous peritonitis case at advanced age presenting with chylous ascites. Turk J Gastroenterol 2012; 23: 423–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anbarasu A, Upadhyay A, Merchant SA, et al. Tuberculous chylous ascites: pathognomonic CT findings. Abdom Imaging 1997; 22: 50–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hibbeln JF, Wehmueller MD, Wilbur AC. Chylous ascites: CT and ultrasound appearance. Abdom Imaging 1995; 20: 138–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berkowitz FE, Nesheim S. Chylous ascites caused by Mycobacterium avium complex and mesenteric lymphadenitis in a child with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1993; 12: 99–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arsura EL, Ismail Y, Civrna-Karalian J, et al. Chylous ascites associated with tuberculosis in a patient with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis 1994; 19: 973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim KJ, Park DW, Choi WS. Simultaneous chylothorax and chylous ascites due to tuberculosis. Infect Chemother 2014; 46: 50–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jhittay PS, Wolverson RL, Wilson AO. Acute chylous peritonitis with associated intestinal tuberculosis. J Pediatr Surg 1986; 21: 75–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Keaveny AP, Karasik MS, Farber HW. Successful treatment of chylous ascites secondary to Mycobacterium avium complex in a patient with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94: 1689–1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee MH, Lim GY, Chung JH, et al. Disseminated congenital tuberculosis presenting as peritonitis in an infant. Jpn J Radiol 2013; 31: 282–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shaik IH, Gonzalez-Ibarra F, Khan R, et al. Chylous ascites in a patient with HIV/AIDS: a late complication of mycobacterium avium complex-immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Case Rep Infect Dis 2014; 2014: 268527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Prasad S, Patankar T. Computed tomography demonstration of a fat-fluid level in tuberculous chylous ascites. Australas Radiol 1999; 43: 542–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rabie H, Lomp A, Goussard P, et al. Paradoxical tuberculosis associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome presenting with chylous ascites and chylothorax in a HIV-1 infected child. J Trop Pediatr 2010; 56: 355–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sathiravikarn W, Apisarnthanarak A, Apisarnthanarak P, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis associated chylous ascites in HIV-infected patients: case report and review of the literature. Infection 2006; 34: 230–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Summachiwakij S, Tungsubutra W, Koomanachai P, et al. Chylous ascites and chylothorax due to constrictive pericarditis in a patient infected with HIV: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2012; 6: 163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang CH, Chen HS, Chen YM, et al. Fibroadhesive form of tuberculous peritonitis: chyloperitoneum in a patient undergoing automated peritoneal dialysis. Nephron 1996; 72: 708–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rollhauser C, Borum M. Case report: a rare case of chylous ascites from Mycobacterium avium intracellulare in a patient with AIDS: review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci 1996; 41: 2499–2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wu UI, Chen MY, Hu RH, et al. Peritonitis due to Mycobacterium avium complex in patients with AIDS: report of five cases and review of the literature. Int J Infect Dis 2009; 13: 285–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Phillips P, Lee JK, Wang C, et al. Chylous ascites: a late complication of intra-abdominal Mycobacterium avium complex immune reconstitution syndrome in HIV-infected patients. Int J STD AIDS 2009; 20: 285–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Calder JF, Norredam K. Chylous ascites due to tuberculosis. Case report. East Afr Med J 1972; 49: 684–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Roca B, Arnedo A, Almenar L, et al. Chylothorax and chyloperitoneum caused by scrophulodermic tuberculosis. Europ J Int Med 1992; 3: 49–50. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Howard PH, Knudsen KB, White RR. Chylous ascites due to retroperitoneal tuberculous lymphadeniis. Surg Clin North Am 1972; 52: 493–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ekwcani CN. Chylous ascites, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS: a case report. West Afr J Med 2002; 21: 170–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sharma V, Bhatia A, Malik S, et al. Visceral scalloping on abdominal computed tomography due to abdominal tuberculosis. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2017; 4: 3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lv S, Wang Q, Zhao W, et al. A review of the postoperative lymphatic leakage. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 69062–69075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]